Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Scientia Militaria: South African Journal of Military Studies

On-line version ISSN 2224-0020

Print version ISSN 1022-8136

SM vol.50 n.2 Cape Town 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.5787/50-2-1374

ARTICLES

Organisational support to overcome the challenges of extended absences of officers in the SANDF

Adele Harmse1; Sumari O'Neil2; Arien Strasheim3

University of Pretoria

ABSTRACT

Generally, military members are often required to work away from home, resulting in extended absences from their families. International studies have shown the effects of extended absences to be severe and associated with long-term social, emotional and behavioural challenges. Longer and more frequent absences negatively affect member morale and could result in military members terminating their employment sooner than planned to maintain their personal relationships and to ensure the wellbeing of their families. The aim of the study on which this article reports was to explore and describe the experiences of extended absences on members of the South African National Defence Force (SANDF) with specific reference to organisational support to aid both the member and his or her family to cope with the challenges experienced before, during and after absences. In-depth interviews were conducted with 12 senior officers of the SANDF during 2019 and 2020, before the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic. The interviews focused on officers' lived experiences of extended absences due to deployment or military training. The findings indicated that absence generally has an adverse influence on military members, not only due to the challenges they face during the absence, but mostly due to the effect it has on their families. Organisational support is not only required in terms of preparing the military member, but should be extended to include preparation prior to their absence, care for the military members and their families during the period of absence, as well as support with reintegration after the absence. The results of this study show that little support is provided by the organisation, especially during reintegration after deployment, and especially in the case of absences due to training. Organisational support during the preparation phase, during absence and with reintegration could mitigate the stress and negative experience associated with extended absences. With the aim of strengthening the capacity of the armed forces, we propose various initiatives that could assist military members and their families to cope with the additional strain of prolonged separation.

Keywords: absence, army, deployment, family, peacekeeping operations, military, military training, occupational stressors, organisational support

Introduction

Extended absences, and consequently separation from one's family, are part of a military career (Bester & Du Plessis, 2014). In the South African National Defence Force (SANDF), members from across the respective services and divisions are often required to work away from home either on internal or external deployments, or due to military training. Extended absence could be any time that an individual employed by the military is required to be away from home for a period, which could last anything from six weeks to a full year, where the individual often does not return home during this period.

External deployments often include military operations other than war on the African continent, and are primarily peacekeeping missions and humanitarian and disaster relief activities, under command of the African Union (AU) and the United Nations (UN). Peacekeeping operations are mandated to control disagreement between two or more conflicting countries, provide humanitarian assistance as required, and to enforce military agreements or UN mandates. According to Chapter VI of the UN Charter, peacekeeping operations are conducted with the consent of both conflicting parties and are not intended to result in active combat. However, from the peacekeeping missions in which the SANDF has been involved since 1998, it appears that such missions are increasingly becoming volatile, unpredictable and violent, and a move from peacekeeping to active combat could occur within a very short period (Arendse, 2020; Bruwer & Van Dyk, 2005; Dodd et al., 2020). Although these missions seem nonviolent and less austere than belligerent operations, they pose additional stressors to military members that may be just as taxing, if not more so.

SANDF members also deploy internally within the borders of South Africa. Recent internal operations included Operation Prosper, the joint operation between the South African Police Service (SAPS) and the SANDF to control the violence, looting and destruction by rioters in KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng between 12 July and 12 October 2021 (Prinsloo & Cele, 2021).

Over and above deployments, all officers are required to attend long military professional courses and functional training. Military professional courses or functional training ensure that SANDF officers progress professionally and achieve competence as soldiers. Functional courses ensure that SANDF officers progress within their respective careers or occupations. Some of these courses are mandatory to progress to the next rank. Generally, military members are expected to attend these courses every four to five years. However, many senior officers will only be accepted on course once every ten years. Regardless of the time in between courses, by the time officers attend the strategic stage of the officers' learning path, they have spent a vast amount of time on formal training and considerable time away from home (Esterhuyse, 2011). SANDF officers are also required to obtain academic education throughout their military careers, as broad liberal education is the foundation of future professional military officers (Republic of South Africa [RSA], 2015). The integration of academic and military professional content in formal courses thus inevitably results in prolonged training periods.

The operational experience and skills gained during internal and external deployments as well as the military training have a positive effect on promotion and vertical and horizontal career progression (Wilen & Heinecken, 2017). It is therefore normal for officers to volunteer for courses because these absences are essential for career progression.

Despite the reason for absence, separation from one's family is seen as one of the unique occupational stressors of a military career (Bester & Du Plessis, 2014; Campbell & Ben-Yoav Nobel, 2009). "Separation, change, stress and adjustment are common events to all families; however, the demands such events place on military families are unique, especially when they emanate from either war or peace-related deployments" (Kalamdien, 2016, p. 290).

Separation is a family affair in that it has an effect on every member of the family. This is easily explained from a family systems perspective (Scholl, 2019). According to this view, a change in one aspect of the family, such as an extended absence, will have an influence on the homeostasis of the family, and members have to adjust to regain equilibrium. In terms of the outcome at organisational level, the absence of a serving member influences his or her wellbeing and work performance. When military members are emotionally distressed, they are prone to make mistakes, and judgement errors that may be life-threatening during operations (Phlanz & Sonnek, 2002). In fact, members' relationships with their families in general, and specifically their spouses, are factors directly related to combat readiness (Shinga, 2016). Support to both the military member and the family during separation is therefore paramount for the optimal performance of a soldier.

The family of the military member is crucial to the success of the operation or training as they form a core support structure not only during the absence but also during the preparation phases (Kalamdien, 2016). This article focuses on the experiences of stress due to absence and separation from one's family as these were derived from the lived experiences of senior officers in the SANDF who have participated in several sessions of training and/or deployments during their career. The study reported here specifically focused on officers' experiences and organisational support provided to them to cope with the challenges during absence.

Literature review: Stressors during different phases of separation

Stress due to absence is not only present during the absence, but starts and varies during preparation for the absence and continues after returning home (Bruwer & Van Dyk, 2005). Although our study did not solely focus on separation due to deployments, we adapted the four phases of deployments proposed by Scholl (2019). These phases explain variation in experiences during times of absence. There are different approaches to explain the phases during deployment (see Kalamdien, 2016; Esposito-Smythers et al., 2011; Pincus et al., 2001; Sheppard et al., 2010), but there are no phased approaches to explaining absence due to training. Scholl (2019) explains how deployment can be characterised by four phases: pre-absence phase (notification of and preparation for departure), absence (departure period), reintegration (preparation to return), and the post-absence phase (period after return). Although Scholl views reintegration and the post-absence period as two separate phases, Gil-Rivas et al. (2017) describe reintegration as both the preparation for return and the period after return. Accordingly, we will describe the stressors of extended absences in three phases: before absence, during the absence and during reintegration.

Stressors related to the pre-absence phase

The pre-absence phase starts as soon as the military members are informed of the operation or training that will take place and lasts until the eventual separation from the family (Kalamdien, 2016). Even though the member has not yet departed, the pre-absence period can be stressful to both the family and the military member because of pre-deployment training and preparation. During this phase, the preparatory activities often allow little time for military members to spend with their family and to make arrangements for care during their absence (Wisecarver et al., 2006).

Kalamdien (2016) notes that in this phase, both the military members and their families may have to deal with feelings of denial and the fear and anxiety associated with the anticipation of the separation. There may, for instance, be anticipation of loss, fear of harm or death, and the uncertainty of the outcome of the absence. Bruwer and Van Dyk (2005) note that, during this phase, the military members are also concerned about the safety and support that will be provided to their families when they leave.

Pre-absence preparation will largely determine the success of the operation and the well-being of both the member and the family during the separation. If not adequately prepared for the separation, the family members may show signs of maladjustment because they will not be able to cope during the absence. Kalamdien (2016) refers to examples of maladjusted spouses developing psychological complaints, such as depression or alcohol and drug use, as well as physical complaints, such as sleep disturbances or headaches and back pain. A maladjusted family will place added stress on the military member who is away.

Stressors during the absence

The existing literature describes several stressors for the member caused by the period of separation. Daily hassles include unfamiliar surroundings, uncomfortable and sometimes inhumane environmental conditions, a lack of basic needs (such as sufficient food and access to basic sanitation facilities), poor communication, isolation, uncertainty, a general lack of privacy, a lack of recognition, operational stressors (including traumatic events), unexpected extensions of deployment as well as threats to health and life. These may lead to adjustment problems. Uncertainty, confusion, boredom, frustration and limited recreation could lead to maladaptive coping, such as irritability, aggression and alcohol abuse (Buckman et al., 2011; Koopman & Van Dyk, 2012; Van Dyk, 2009). At this stage, some military members may also resort to resigning from the military (Sheppard et al., 2010).

Recent South African (SA) literature focuses on separations due to peacekeeping operations (Dodd et al., 2020; Mtshayisa & Letsosa, 2019; Zungu & Visagie, 2020). These operations have unique characteristics, with each operation resulting in its own unique stressors. These stressors comprise military members' general attitudes towards the reason for deployment, confusing communication between participating multinational countries as well as cultural alienation during external deployments. Being removed from familiar environments and social support networks, such as friends and family, will increase the stress experienced during the operation. Furthermore, major life events, such as the illness of a child, death of a partner or even an unexpected divorce could add to severe emotional burdens (Bruwer & Van Dyk, 2005).

Kalamdien (2016, p. 296) describes the adjustment of the family during this phase as an "attempt to re-establish their equilibrium following the departure of the serving member". Heinecken and Ferreira (2012) depict the heavy burden placed on family relationships during operations in Burundi, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Sudan. Dwyer and Gbla (2022), on the other hand, explain how problems at home are a constant worry for soldiers from Africa who cannot always rely on organisational interventions to ensure the safety and wellbeing of their loved ones.

During their absence, communication between members and their families is central to their well-being. Communication with family usually relies on the infrastructure available, and in some deployments, especially in Africa, this infrastructure is not readily or consistently available (Dwyer & Gbla, 2022; Heinecken & Ferreira, 2012). Even when infrastructure is available, the fact that one is not there to help or deal with the problems back home is very stressful. Even everyday problems of running the new single-parent household or not being able to help the family cope at home are stressful to both the family back home and the absent member. During this phase, military members often experience major stress, and this affects their ability to cope and function as required (Bruwer & Van Dyk, 2005; Heinecken, 2020; Heinecken & Ferreira, 2012).

When the family unit and spouse support the absence and it is possible for the military member to still feel part of the daily activities at home, the stress associated with the separation is not felt as severely as when there is a strong sense of alienation and not being part of the family anymore (Heinecken & Ferreira, 2012). The pinnacle of negative experiences during absences is particularly related to absence from children (Heinecken & Wilen, 2021), especially because children may experience crucial developmental milestones (i.e. first words, first steps and first day in school) during the absence.

The family at home is inevitably also concerned about the safety and wellbeing of the absent member. Even during peace operations, this is a serious consideration, as was shown in the deployment of SANDF soldiers to the Central African Republic (CAR) in 2013, which resulted in the death of 15 soldiers (Heinecken, 2020). Deployments in Africa, regardless of their nature, pose the risk of death and serious injury. In the first month of the deployment phase, the family also experiences a "sense of abandonment, loss, isolation, sadness, emptiness, pain and disorganisation" (Kalamdien, 2016, p. 296). In the months to follow, the family will usually adapt and learn to function without the military member at home. They will assume new roles and take on new responsibilities.

During extended absences, it is difficult, if not impossible, to maintain relationships with spouses and children, which could lead to separation and divorce. Mtshayisa and Letsosa (2019) confirm that the duration of absence due to deployment has an adverse effect on the marriages of SANDF members. Buckman et al. (2011) report that military members in the United Kingdom terminate their employment early to save their personal relationships and to ensure the mental well-being of their families.

Scholl (2019) notes that the family unit is an essential factor in the well-being of children. Accordingly, the absence of the military parent also affects the well-being and development of children. Kalamdien (2016, p. 290) confirms this by noting:

[It is not only the] serving members who may lose their lives, become seriously injured or mentally scarred as a result of their deployment experience, but a frequently overlooked casualty of deployments are also their families back home. These families become psychologically and emotionally scarred by these events.

Stressors related to reintegration

Reintegration refers to the process of managing the return of a military member to civilian life (Gil-Rivas et al., 2017). In this phase, there may be intense anticipation for the reunion but, at the same time, some worry about the way the reunification would play out. Kalamdien (2016) notes the importance of preparation for the adjustment to a reunion at this point, which is just as important as the pre-absence preparation.

During reintegration, military members must return home and reintegrate into the normal everyday life of the family (Heinecken & Ferreira, 2012). Reintegration is a stressor, as both the family unit and the military member have grown and changed during the absence. Heinecken (2020) notes that homecoming is both a joyful and stressful experience. There will typically be some role confusion and negotiation to establish equilibrium in the family during this phase.

Reintegration is important after an extended absence. All military members that are deployed on a mission (regardless of the type of mission) have some extent of mission stress that will make it difficult to reintegrate into the family and civilian life (Heinecken, 2020). The stress associated with the absence often continues in this phase, with the challenge of reintegration of the absent member into the family (Carter et al., 2019; Moelker & Van der Kloet, 2006). Upon return, the military members may show symptoms of depression, anxiety, acute stress, and even post-traumatic stress disorders (Johnson et al., 2007; Sheppard et al., 2010).

Heinecken and Wilén (2021) point out that both internal and external factors influence the reintegration of the military member in the family. External factors relate to the nature of the member's duty during the absence as well as socio-economic and demographic factors of financial status, rank, and length of the deployment. Internal factors are those related to the military members themselves, and include aspects such as their family relationships and their mental state at the time of the reintegration. For the absent members, internal factors make reintegration during this phase difficult since they need to renegotiate their prior roles in the family after their absence (Kalamdien, 2016). External factors include how well the members were prepared for the reintegration as well as the duration of the absence.

Several studies have been conducted focusing on the length of deployment and its effect on the military member (Adler et al., 2005; B0g et al., 2018; Buckman et al., 2011; Sheppard et al., 2010; Stepka & Callahan, 2016; White et al., 2011). For militaries across the globe, the typical duration of deployment ranges between six and twelve months (B0g et al., 2018). One of the main contributing factors to operational stress is extended deployment, as it directly influences the separation from one's family (Buckman et al., 2011). Ntshota (2002) as well as Bruwer and Van Dyk (2005) found that the length of an operation was a great stressor to military members, and that the longer the absence, the more challenging it became for the member to cope. Shorter and more regular deployments have a less severe effect on members and their families, with longer deployments strongly associated with maladjustment of the children (Sheppard et al., 2010). It is, however, difficult to say what the ideal period of absence would be, since military members differ in their views: for some, three months are too long; for others, nine months are unbearable (Neethling, 2011). It is interesting to note that, despite all the challenges military members face due to extended absence, many develop mental resilience over time, and this can result in them being tolerable to longer periods of absence with fewer rest periods in between (Street et al., 2009). However, as noted by Hosek et al. (2006), although the preferred time of absence may increase, every military member has a preferred time of deployment. Should the actual time of deployment extend beyond the preferred time of deployment, the member might not want to deploy again and may even resign from the organisation.

The current study

In the current study, the aim was to explore and describe how officers in the SANDF experience extended absences, with specific reference to organisational support in aiding both the military member and the family to cope with the challenges they faced. There is a considerable amount of international literature available on the effect deployment has on members and on their families. Most of the studies refer the challenges experienced by deployed soldiers of the US military forces (see Adler et al., 2005; Carter et al., 2019; Chartrand et al., 2008; Gorman et al., 2010; Hobfoll et al., 2012; Hosek et al., 2006; Johnson et al., 2007), or the effects deployments have on children (Lyle, 2006; Pexton et al., 2018; White et al., 2011) or on spouses (Padden et al., 2011). A few studies with similar focus areas had used samples from other countries, for example the Slovenian Police Force (Lobnikar et al., 2011). Over the last couple of years, emphasis was placed on the effect of peacekeeping missions rather than combat.

Similar studies on the effect of deployments among SA military families are relatively limited with more recent studies focusing exclusively on peacekeeping missions. Koopman and Van Dyk (2012), for example, focused on the challenges experienced by SANDF soldiers during peacekeeping deployments in Sudan, while Wilen and Heinecken (2017) considered the effect of peacekeeping deployments on SANDF soldiers' perception of their career advancement, status and reintegration. Neethling (2011) studied coping during peacekeeping missions. Both national and international studies on experiences of absences assess combat or peacekeeping, omitting the challenges experienced by extended absences due to training. The current study was an initial attempt to fill this gap by focusing on the experiences of the support received from the organisation during prolonged absences, such as during deployment and training. To understand the needs for support, it is important to highlight the challenges officers experience during their absences. The study aimed to explore and describe the challenges associated with extended absences and the experiences of organisational support before, during and after absences.

Methodology

This section introduces the qualitative method that was used, and explains the research design, the participants, as well as the methods for collecting and analysing the data.

Research approach and design

The current study utilised a qualitative, phenomenological approach since it afforded us the opportunity to explore and describe the lived experiences of the participants (Chilisa & Kawulich, 2012; Creswell et al., 2016). An explorative and descriptive aim was appropriate because, although studies focusing on organisational support to soldiers have been conducted, they focused solely on support during deployments and did not include absences due to training. Qualitative research is however inherently interpretive since the data cannot speak for itself (Willig, 2013). Our interpretation used a phenomenological lens to understand the meaning of the lived experience of absence from the point of view of the participants.

The first author conducted in-depth semi-structured interviews with 12 participants who were officers in the SANDF at the time of the study. The rich and complex data collected reflected the realities, interpretations, experiences, perceptions and narratives of the participants (Saunders et al., 2016). Since we were approaching the study through an interpretivist lens, it was important that we collected data to understand the meaning that the participants created from how they experienced the realities of the absences they experienced. To do this, emphasis was placed not only on the data directly related to the research question, but also on the context in which each absence took place. Using in-depth, semi-structured interviews allowed exploration of these contextual factors (see Scotland, 2012).

At the time of the study, the first author was employed as a senior officer in the SANDF. The second author was a previous employee of the organisation, at the time of writing this article, living with a spouse working in the SANDF. It is therefore fair to describe this study as taking an insider stance. Insider research refers to research that is conducted by members of an organisation or system (see Greene, 2014; Mercer, 2007; Wilkinson & Kitzinger, 2013) as opposed to researchers joining an organisation solely for the purposes of conducting research and only for the duration of the research. Insider researchers are seen as "native to the setting" (Brannick & Coghlan, 2007, p. 60) and have insight into the lived experiences of members of such organisations. Working from an interpretivist paradigm allowed us to use our experiences to understand the lived experiences of the participants.

Although personal experience may cloud one's judgement and could lead to bias in the interpretation of participants' experiences, we consciously used a process of reflexive awareness during the analysis of the data to articulate specific knowledge that has become deeply entrenched due to the insider's understanding of the organisation where the research was conducted. It was important to make known our own understandings and to separate these from the stories shared by the participants. In this way, although we could use our own knowledge and understanding of absence from home (or in the case of the second author, the absence of a spouse), we made sure that these experiences were not the focus of our analysis. With the SANDF, being a closed organisation with a unique culture, insider research did not only allow us first-hand insights, but also granted us easy access to rich data as we could draw on our understanding of the linguistic, emotional and psychological principles of the organisation, and our understanding of the participant during the interviews (Chavez, 2008; Wilkinson & Kitzinger, 2013).

Research participants

A purposive (judgemental) sample of 12 officers was selected (see Etikan & Bala, 2017). Based on the criteria for selection, these officers were all either married or in a life partnership during the time of their absences, they all had children and were deployed at least once, or had attended at least one long military course (Topp et al., 2004). According to Saunders (2012), the ideal sample size for semi-structured interviews is between five and thirty participants. Sample size should however not be the major determining factor in selecting a sample; the focus should be on the quality of the data and the depth of understanding of the participant experience it affords (Fusch & Ness, 2015). The ability of the participants and their willingness to share their experiences were therefore the most important considerations during sampling (Etikan, 2016; Saunders et al., 2016).

Data collection

After institutional ethical clearance had been given by the SANDF (DI/DDS/R/202/3/7, 19 November 2019), the participants were contacted to arrange the interviews. A pilot interview was conducted first but was added to the data as no changes were made to the interview guide after the interview (see Adams, 2015; Blumberg et al., 2005; Saunders et al., 2016). Face-to-face and virtual semi-structured interviews were conducted between November 2019 and February 2020. The interviews took the form of relaxed conversations where participants engaged on matters related to the absence and which were important to them (Longhurst, 2010). The conversation was guided by asking questions regarding the nature of the absences experienced, the frequency of absences, as well as the major challenges and support structures on which the participants and their families relied. Throughout the interviews, the interviewer strived to meet the participants in their natural settings and not to exert bias, surprise or excessive empathy towards any of their responses (see Creswell, 2014). Where participants could not be met in their natural settings, such as where participants were in other provinces, the interviews took place via Skype and WhatsApp video call. The interviews were recorded with the consent of the participants, which was obtained prior to the interviews.

Since the topic could have been very traumatic for some participants, the social worker at the Area Military Health Unit was available to assist if the interviews caused any distress. In planning for the unfortunate event where an emergency might occur during an interview, the Directorate Psychology at 1 Military Hospital in Pretoria was informed of the study, and psychological support was on standby for the period during which the interviews were held. None of these services were needed during or after the interviews.

Data analysis and interpretation

The interviews were transcribed and then analysed. Qualitative data analysis involves reducing collected data to a manageable data set, developing summaries, and establishing patterns in the accumulated data (Blumberg et al., 2005; Saunders et al., 2016). We used the process of thematic analysis as proposed by Braun and Clarke (2006), which comprises six phases: familiarisation, generating codes, generating initial themes, reviewing the themes, defining and naming the themes, and reporting of the findings. The analysis comprises a cyclical process, working back and forth between themes, codes and raw data on the one hand, and the research questions on the other, to ensure thoroughness and coherence in the study (Morse et al., 2002). The initial coding was conducted in ATLAS.ti 8, and when the codes had been finalised, the categorising and thematising were conducted manually. The themes extracted firstly focused on the participants' general experiences during the absences, and specifically the challenges they experienced; and secondly, their perception of the organisational support during their absences. The major themes are discussed in the Findings section with verbatim quotations to justify and illustrate our thematising.

Data integrity

The credibility of a study utilising interviews is largely influenced by the trust relationship between the interviewer and participants. Trust, on the other hand, is influenced by the ethicality with which the study is conducted and the relationship that is established (or which exists) between the interviewer and the participant. If participants trust that the data will be used confidentially, they are inclined to provide truthful versions of their experiences. In this study, informed consent required that detailed information on the topic of the study be given to the participants when they were invited to take part. They were assured that their participation would be confidential and anonymous, and that it would not have any negative consequences for their careers in the SANDF (see Bryman & Bell, 2014). There was full disclosure of the procedures and purpose of the study (see Blumberg et al., 2005), and of how the information and content would be made available. The participants were also treated with dignity, and were ensured that they would be protected from potential physical or psychological harm (Van Zyl, 2014).

We also agree with Chavez (2008) that being an insider researcher increases the credibility of the study since the interviewer is knowledgeable about the language and shares the culture of the participants. With an insider researcher, however, there is the risk of socially desirable responses (Krefting, 1991); therefore, it was important to conduct the interviews in such a way that the participants did not experience it as threatening or judgemental. The interviewer was mindful to build trust when conducting the interviews by utilising probing questions and investigating responses related to various scenarios (Saunders et al., 2016). Techniques were applied to ensure that the participants' socially constructed realities matched the initial intent of studying their experiences during absences, for example, an interview guide was used to ensure that questions asked were related to the research question. The interviewer also guided the conversations back to the topic when the conversations strayed.

In terms of sampling sufficiency, the study yielded rich and robust qualitative findings despite the small sample (see Young & Casey, 2019), and in all probability represented a considerable range of the experiences of senior officers in the SANDF. All the participants had been exposed to either deployment or long military courses, or both, in their military careers of fifteen years and longer. The interviews were conducted, recorded, transcribed and submitted to the participants to confirm accuracy of the content, and to make sure it was a true reflection of the interview.

We considered the confirmability of this study by consulting:

• journal articles of recent SA studies (see Mtshayisa & Letsosa, 2019; Neethling, 2011; Ntshota, 2002);

• the work of fellow researchers (see Bruwer & Van Dyk, 2005); and

• peer debriefings with colleagues in the SANDF, who had performed similar studies in the past, and who were considered able to relate and corroborate their findings to be consistent to the findings of this study. This was done in an informal way, by means of continuous conversations throughout the duration of this study.

Findings

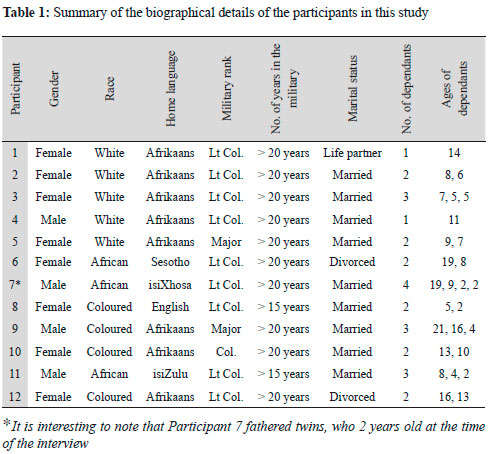

Table 1 provides a summative description of the biographical and demographic particulars per participant. Most of the participants self-identified as female (f=8), white (f=5), Afrikaans (f=8), lieutenant colonel (f=9), with more than 20 years' experience serving in the SANDF. Many of the participants were from Gauteng (f=7), with five from the Free State, two from KwaZulu-Natal, one from North West, and one from the Western Cape.

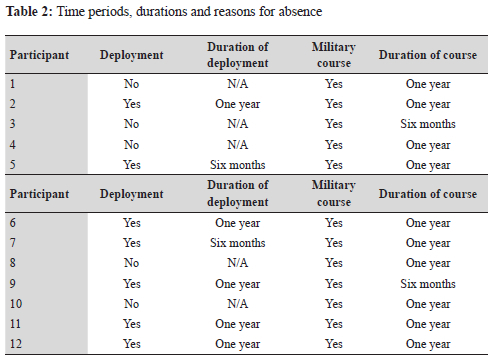

The reasons for absence cited by the participants were due to both deployments and training. The duration of absences ranged from three months to one year, for any absence, with limited opportunities to return home during those periods. Table 2 illustrates the type of absence (i.e. training or deployment) per participant, and the longest duration of such an absence.

Although the participants acknowledged the fact that the absences put strain on them and their families, many of them volunteered for monetary reasons, or for the prospect of career advancement. Many SANDF members want to enjoy financial freedom, and they can easily reach that with funds earned through deployments. Training opportunities also have indirect monetary value in promotional opportunities. The attendance of training is an explicit requirement for SANDF members to complete certain developmental courses in order to be found competent on their level of functioning, or to be eligible for promotion. Upon successful completion, such training will most probably lead to rank promotion and result in a salary increase. As Participant 1 noted: 4

Eventually it boils down to a salary, I mean, it's your progression in the organisation. And the fact that you do decide to go, it will mean progress as promotion, it means more money. It means you can actually have a career path hopefully a little bit better. So, it's a conscious decision you take, you know you are going to sacrifice quite a lot. If it was not a promotional course and it was only for development, I would not have done it.

Training opportunities also have a direct financial implication due to the daily allowances that attendees receive for compulsory live-in courses, which they receive in addition to their monthly salaries. One may find that, in the instance where the duration of a course is one year (theory and practical phases), one may earn substantial amounts in course, danger, deprivation and subsistence and travel (S&T) allowances.

Some participants, however, also attended training courses to learn a new skill. Participant 2 for instance said:

There's a lot of people that say they only do the course for promotion. And I think that is 95% of the people that go for that. My take was that I actually wanted to learn something (on the course).

The duration and frequency of absences are factors that contribute to the stressors military members experience (Hosek et al., 2006). All the participants had been on extended absences from home due to numerous deployments or training opportunities, or both. One participant noted:

The last one (absence) was due to training, though most of those prior to that were deployments. (I was absent) almost every year, except for 2018. And it even goes further back than five years actually, but in the last five years, almost every year (Participant 11).

Participant 11 had experienced so many absences in his military career that he failed to recall the exact number.

Experiences and challenges during extended absences

Although the focus of this study was on the organisational support that the members had experienced during their absence, it is important to highlight the emotional experiences and challenges to contextualise the support that is needed. The participants all agreed that extended absence brings about stress in the lives of members and their families. Participants reported experiencing the absences as emotionally strenuous and associated with considerable negativity. Participant 12 said:

It was quite hard, I must admit, I cried a lot, especially over weekends when all the students are going home who are staying in Pretoria, and I have to stay behind. So yes, it was hard.

Many of the negative experiences were associated with family events and milestones that they could not attend. Some extracts from the data that highlight this are:

You were not there when your child won his tennis match. You missed out on that. You were not there when your partner experienced a compliment from a senior officer, and he could share that with you. You were not there when they had a bad day (Participant 1).

It wasn't nice. I hated leaving. Honestly, I hated leaving. And I knew exactly what I am going to miss while I was gone, so it made it worse. It was the end of the year, and all the concerts and everything, so it's terrible (Participant 3).

Things like, I will never have my daughter's first high school day. I will never experience it with them. It doesn't matter what I say, it doesn't matter what I do; I wasn't there. And I think, for me, it's more guilt that will keep on coming back (Participant 10).

The negative emotional experiences were not only related to being away but also to the damaging effect it had on participants' families. Military families are unique in the sense that they deal with stress far more frequently than their civilian counterparts, caused by the possible relocation due to transfers and promotions, absence of one or both parents due to deployment or training, and trauma due to challenges associated with the demands of the military (Palmer, 2008). Children, regardless of age, experience the absence of a military parent as taxing (Knobloch & Wilson, 2014). For example, Participant 4 shared:

Eventually when the course was done, I said we can't believe eleven months are gone, but during the eleven months, it was too long. I think you do a lot of damage to a normal family, a happy family by separating them for such an extended period. A lot of people say it's a good thing because if you can withstand that, that's utter nonsense. We are a very close family, and we live for each other. That's it. That's my reason for living. So, by now separating such a family, it's tough. So, for me it was tough, it was really not an easy ride, eleven months. It was tough.

During the interviews, the participants found it particularly difficult to speak about the emotions associated with leaving their families. They vividly remembered actual scenarios, actual discussions with their spouses and partners, and conflict between them and their families prior to or on their return after the absence. They remembered the days they had to bid their families farewell, and the hurt they saw in their children's eyes.

If I had to go away, it was not easy. I was crying up until the first tollgate [...] and ja, I think there was a bit of insecurity. He [the son] always wanted to know, when must you go away again (Participant 4).

We went for counselling and stuff, but the counselling also opened a lot of wounds. Because you have to talk about things that you don't want to talk about (Participant 8).

The absence further puts a constant strain on the work-life balance of military members.

Within my emotional state of mind, I have experienced a feeling of worthless-ness. I lost my value. As a businesswoman, I continue because I am climbing the ladders. But as a mother and as a wife, it feels as if I'm losing there (Participant 5).

[I felt] helpless and angry, because personally, I didn't feel that being away from your house for so long was actually worth it. You literally feel like you are not welcome in your own home. And the strain on your marriage, it's terrible (Participant 2).

The challenge of an extended absence is not only the absence itself, as the challenge starts before the absence and continues after the return. The most noticeable challenge for participants during the absence was that they could not support their families. Participant 11 summarised it as follows:

It's not easy (being absent from one's family), it really is not. In recent times, you worry when you are away because the level of security in the country is not good. So, you just think, when you are not there when they are on their own, what is going to happen to them? So, it was not a good experience; however, somebody has to do it.

Since they were not at home to fulfil their parental tasks, they often had to request assistance from family or friends. This is similar to findings by Dwyer and Gbla (2022) who note that, especially in poorer African countries, soldiers will tend to worry about the well-being and survival of their families. In African countries, the military member is often the sole breadwinner in an extended family of dependants.

Due to the long periods of absence associated with the already emotional situation, participants reported that they often missed large parts of their children's lives, and from their perspectives, it had lasting effects on them and their families.

I was dependent on other parents to be the transport for my child with his sports coaching, driving him up and down to tennis matches. I also had a meeting with the teachers, to notify them of my long absence, and that I would not be available as I would under normal circumstances, that I will not be so much involved in my son's schoolwork, checking for homework (Participant 1).

Some participants said they often experienced feelings of helplessness and frustration, especially when it came to their children. From the interviews, it was evident that the participants were committed parents who would move mountains to provide for and care for their children. However, due to their absence, they were unable to provide the physical and psychological support their children needed at times. They had the following to say:

As a mother, children getting sick. Because before I went, while I was on the course in 2016, my daughter was very sick. I got a call, they have to rush her to hospital, because she can't breathe properly, and stuff like that. So, that was my biggest challenge, what if something serious happens to her while I am in Bloemfontein (Participant 8).

Not being part of their educational processes was a challenge for me, as a mother. And not being there for special times in their lives, like their birthdays, and their achievements. I felt like an outsider, because I couldn't share it with them, or they couldn't share it with me. Not being able to assist my son with his school projects (Participant 12).

Contact with family is also reliant on the infrastructure available at the place of their absence. One participant was confronted with being away from home over the festive season. The deployment period was extended without warning, which caught the member and his family off guard. At a time when families are together after a year of hard work, he had to leave his family behind due to deployment to another country. He explained the experience as follows:

We've flown out on the tenth of December. So, we had to spend Christmas in Congo. So ja, it's in a different country, it's not what you are used to. So ja, we are singing Christmas carols but ja, you're not home and there are no telecommunications, there was no communication. But ja, as a person without the family that you are connected to, it's always difficult. It's difficult (Participant 9).

One of the biggest stressors to a serving member during an absence is a mismatch between the expected time of return and the actual time of return, as was the case with Participant 9. This could be due to an extended operation, or due to logistical challenges. Whatever the reason, a mismatch between timings has a severe adverse effect on military members and their families (Buckman et al., 2011). When these members were, for example, expected to remain in the deployment area, it negatively affected their wellbeing.

He [husband] was frustrated, especially with the fact that I would tell him the Friday that we are coming home. And then, quarter to four [on Friday] they would tell us we cannot go home, for some ridiculous reason (Participant 2).

A contributing factor to this adversity is found when the organisation does not prepare the members and their families for the possibility of unexpected extensions of absence. Families often did not understand why the member did not return home on the said date. The participants found it difficult to maintain their relationships during the absences. Both the family and the participant had to adapt to functioning individually. As noted by Participant 10:

You know, there are days when I want to scream, because I'm having, she's [referring to the spouse] not a teenager anymore. She's a girl that knows what I want and how I want to do things. And now suddenly I come back and I'm making everything to be messed up ... It's actually sad, because now I had to realise ... Now you must back off, these people must get used to you.

Often, during the absence of the military members, the primary caregiver is solely responsible for the wellbeing of his or her family, looking after the psychological, emotional and physical needs of their children, all while protecting their children from the stress the absence presents (Stepka & Callahan, 2016). The primary caregivers must take full responsibility for the children and look after their emotional and behavioural needs, and should simultaneously strive to maintain the daily routine, while they are also confronted with their own stress in how to deal with the absence of their spouse or partner. In many cases, this resulted in a family growing in independence and learning to function effectively without the military member.

[I]f you're a father, you are taken as the head ... imagine when you are away for a long period of time, they try their own way of doing things . when I come back, reunion becomes difficult (Participant 11).

After an extended absence, the participants often felt as though there was no place for them in the family unit on their return, or as noted by Kelley et al. (1994), being out of sync with their families. As noted by Participant 8:

On the marital side also, your husband gets used to you not being there, and he starts having his own friends. It's an adjustment because you would say, but I'm on course, but he will say, but I'm alone, so I needed to make friends.

Upon return, there is also a period of adaptation in which the family as a unit needs to adapt to the return of the absent member. Reintegration into civilian life may inevitably be a strenuous, challenging and complex problem, for both the serving member and the family. The military member is returning to a world much different from the one he or she had left behind (Macintyre et al., 2017). During the interviews, many participants mentioned that they were returning to a household where the primary caregiver had established new routines, and where children had grown up, both physically and emotionally. As much as military members often do not return home as the same person, they often find a different household on their return. As a result, in many cases, the reintegration of such military members into their families result in conflict and stress -for both parties.

Unfortunately, in some cases, the family unit struggles to return to a fully functioning unit. This may result in separation or even divorce. Participant 12 shared that she found out her husband was having an affair while she was on course in 2017. Upon her return, this resulted in separation and eventually divorce after 19 years of marriage:

I then found out that he had an affair with a woman since 2017. I went to the home where he was staying with his girlfriend, asking him to come home so that we can work on our relationship. He came home for a while, but we never spoke. He eventually moved out of the house.

For participants, the absences due to training were not different from absences due to deployments. The experiences of the participants were generally similar to those found in previous studies discussed in the literature review of this article.

Experiences of organisational support

Participants were prompted about their experiences of organisational support. The findings are presented here as experiences of support before the absence, support during the absence, and support after the absence. Kalamdien (2016) describes the influence of resilience on military family wellbeing as a core aspect of being able to cope sufficiently with the absence of the military member. This is echoed by many international scholars (see for example Mancini et al., 2018). Resilient families will not experience less risk or adversity but will have the ability to adapt to the changing circumstances. Support in well-being and resilience is therefore "paramount to any military" (Kalamdien, 2016, p. 300). In this context, resilience is seen as the ability of both the individual as well as the family to bounce back in the face of adversity and return to a relatively normal level of functioning (Mancini et al., 2018). Efforts of organisational support may therefore ensure that both the member and the family are resilient. In this section, we turn our attention to the experiences of organisational support from the military member's point of view.

Support before the absence: preparation for the absence

Preparation of military members for operations is ingrained in every member's training, from basic military training to mission readiness training. Support prior to a deployment is seen by Kalamdien (2016) as the planning phase of support that should include psychological, spiritual, financial and security concerns, and should function at both individual and family level. Preparatory training programmes may present one way of organisational support in assisting members to deal with the absence. This training may include anything from mission readiness training to wellness and resilience development (i.e. resilience training). The resilience training presented by the SANDF is a training programme that intends to promote mental health; develop emotional, physical, mental and behavioural toughness; prevent the development of physical and/or emotional distress; and enhance adaptation in dealing with possible adjustment problems. However, when the participants were asked whether they or their families had received any training that prepared them psychologically for being absent from home for an extended period, the following responses were provided:

The one girl [a social worker] just came and said, you have to be spiritually strong and your marriage must be strong, and you must be strong and that was pre-counselling - if you can say that (Participant 2).

There was no [formal] programme that prepared us [for absence due to training], so we had to use the two months prior to the course to, you know, just to get used to the idea. Yes. And to say how we are going to handle this. We did not really have the answers (Participant 4).

Some participants experienced a comparable programme, not necessarily called a preparatory programme, but an effort from the SANDF to prepare them for the absence. They mentioned these initiatives:

While I was working there [in Bloemfontein] as part of the preparation for external deployment, there was continuous interaction from the unit with the social workers because as they do the resilience [programme] with me, at the end of the day when you are not around, they [the social workers] have to go and confirm that these things are in place [at your home] (Participant 9).

We had a programme to start to know the people that are going with you (overseas). They will teach you about the norms, culture, everything like that. So, in a certain way, they prepare you to know that this country, this is how the country operates. But in terms of preparing you how to cope while you are there, it's not happening (Participant 10).

Other participants did not agree. They did not participate in any formal preparatory programme. They said they would have appreciated an intervention that would have prepared them for the stressful event that lay ahead and which would have aided them in preparing their families on how to cope with their absence.

There was no formal programme to prepare the family. We tried from our side to make sure that everyone knew what was expected or what was going to happen. But nothing you can do, nothing can prepare you completely for what awaits you (Participant 2).

No. That time we didn't have such things [formal preparatory programmes]. But if maybe there was a session to say, this is going to happen and what are you then going to do, so that by the time we say yes, I can go and be deployed, then we know our families are okay. Maybe then we would not divorce (Participant 6).

Training that will benefit specifically the family would include a focus on the meaning of the absence. As noted by Participant 5, some aspects of military absences may not make sense to civilians. This participant had attended a training course in Pretoria, and she was absent from her family in Bloemfontein for almost one year. Teaming up with other students on the programme, they tried to travel to Bloemfontein over weekends as often as they could. However, as she explained, the travels were not always allowed, nor was staying at the unit often understood by the family.

When I'm on course, I have to attend a bar function almost every Friday evening, so now they [my family and friends] want to know why I am going to the bar every Friday evening, why can't I come home! It's part of course tradition, it's part of military culture. So, it's not just a matter of "sorry guys, I'm a party pooper, I'm not going to the bar, I rather want to go home", because I must form part of the cohesion group of the course as well. And at the end of the day, for esprit de corps, on course as well, you must take part in things which is not understandable necessarily at home. So, somebody may say my husband is a staff member; he understands that. But for the bigger picture, for those who do not understand, it looks as if I'm having a jolly time on the other side, while they are sitting at home, waiting for me to come home. And those types of traditions and things need to be explained, because how does it work if I can leave early every Wednesday, but I cannot leave early on a Friday. So why don't they swop the two around, things like that that need to be explained? Because it's only me telling them that. It might be that I'm now just making up stories to make it look good while as I'm busy with other things.

Research on peacekeeping deployments indicates that military members have a strong need for their families - and the larger society - to perceive their efforts during the deployments as meaningful (Heinecken, 2020). Soldiers want to believe in the value of the sacrifices they make and the good they are contributing when deploying. It is thus important for soldiers that their experiences are viewed in a positive light (Bartone 2005). Supportive families and spouses also reduce the stressors experienced during deployments (Adler et al., 2003). As reported by some of the participants and in multiple studies, having a family that understands the meaning of a military culture will support the military members' efforts even during training.

Although preparatory sessions appeared to be more readily available for military members deploying, this seemed not to be the case for members leaving home for training opportunities. In the case of deployments, such as peacekeeping operations, members are timeously informed of imminent deployments in the SANDF. It is safe to say that SANDF members are aware of when they are going to be deployed, as the majority of members volunteer for deployment. However, training opportunities, such as developmental training, are announced unexpectedly, sometimes a few days prior to commencement of training. This often results in very little time for preparation opportunities on the side of the organisation and of the individual going on training, and his or her family unit. The participants also noted that preparatory opportunities might benefit the family as a whole.

I just think, if something similar [preparation programme] could have been done for my son and my wife, that would be awesome. Specifically, for a little boy that doesn't understand, you know, to have this explained to them (Participant 4).

If there was a programme, they [the family] would have benefitted from it. I will try to present my resilience programme at home. But from the unit or the DOD [Department of Defence], your family is on their own. If there is any resilience programme that they require, you as the head of that family, you will decide what they require, and you will do your own. The DOD does not go to family and say, be prepared. No, they don't (Participant 7).

You will come home, and you will tell your family, the country [overseas] is this, and it is like that. But in terms of preparing them how to cope, it's [preparation programme] not there. If it [preparation programme] would have been a family thing, it would have been so nice (Participant 10).

When asked whether the families would benefit from such a preparatory programme, participants suggested that a new well-structured programme, with age-appropriate information for the children and knowledge and skills for the spouse, would serve a purpose. It would potentially strengthen the hand of the member who needs to prepare a family for his or her absence. Participant 1 had the following to say on the matter:

Maybe just to have a contact person that can give you some points or hints, let's say advice as to, listen, did you think of this, did you think of that? Do you have a support system in place if, in case of emergency, or just the daily things that you don't necessarily think of? I think that would definitely be beneficial.

The organisation plays an important role in ensuring readiness for the military family. Readiness is described as "the state of being prepared to effectively navigate the challenges of daily living experienced in the unique context of military service" (Meadows et al., 2016, p. 2). Families who are 'ready', are equipped with the necessary knowledge and skills to deal with the challenges effectively and they are aware of the resources provided by the organisation. In the SANDF, military members undergo pre-deployment training to prepare them for deployment and to deal with being away from their families. However, the participants in the current study expressed their concerns about the absence of preparatory training for their families that would assist them to cope with the absence.

The only information military members are able to relay to their families is what they are being taught during pre-deployment sessions and through years of work experience. Unfortunately, this is not sufficient information to prepare the spouse and children remaining behind. Participants all commented that they had to prepare their own families for their absence, not always knowing what to say or how to communicate the expectations. It was evident from the responses of all participants that the SANDF does not provide any preparatory programme for families to equip them with the required skills and knowledge to deal with the challenges the absence may bring.

Both readiness and resilience development are important in preparing families for separation. Resilience refers to the individual's ability to 'bounce back' after experiencing stress or stressful events, and is the ability to withstand, recover from and grow in the face of stressors and changing demands. Organisations, such as the SANDF, can help military families experience readiness by developing and nurturing resilience. The SANDF has a vast amount of expertise in the South African Medical Health Service (SAMHS), in its static Military Health Support Capabilities, where they render health sustainment to military members and their families, and any other eligible forces (RSA, 2015). These capabilities can provide mental health training to families prior to, during and after deployment or long training opportunities.

Support during the absence

Some participants felt that the support they received from the unit and direct colleagues during the absence was adequate:

I know I can phone any of my colleagues and say, listen here, my husband is having a problem, please do this, or help him with this, and they would have helped (Participant 3).

Unfortunately, not so much [support] from the military side, there was not a lot although she [the participant's wife] knew all my colleagues; so, if she needed something, she, there was somebody that she could have asked (Participant 4).

It seemed from the responses that, from the unit side, the officer commanding (OC) has an influence on the support that members receive. For example, while Participant 9 was on course, he received news that his wife was in labour. The OC sent a chaplain to provide his wife with transport and psychological support, and ensured that the participant attended the birth of his child:

No, the OC had to organise and liaise with Infantry School commander. To say there is a situation. So, yes, he must attend [the] practical [phase of the course], but he needs to attend the birth for two days. A chaplain was tasked to take my wife to the hospital while I'm on my way from Oudtshoorn in a bus. When they took my wife in for labour, I was at the door. And here stands the chaplain (Participant 9).

It does however not seem as though there is a consistent culture of support at all units, or throughout the levels of the organisation. Participant 11 explained it as follows:

The only thing, [you are] just on our own, the organisation, we don't receive much from them. I don't know how to explain in terms of who is supposed to do what exactly. But not even a card from the unit, or something that would show that somebody is thinking of you.

Participant 8 also noted:

Because after this course [reason for extended absence], a lot of people get divorced. A lot of people's lives just go the wrong way. Preparing people, and also talking to them throughout the year, will assist. Because we were just left. Resilience [resilience training prior to the absence] and then we carried on through the year, and nobody actually checks on you, are you still in the right state of mind to continue on this course.

Support after the absence: reintegration into the family unit

Reintegration initiatives could have a considerable effect on military members and their families in understanding possible conflicts that may arise on their return after extended absence. The function of a reintegration initiative is to assist the member and his or her family with the re-entry and effective functioning after return from an absence at both personal and societal level (Heinecken & Wilen, 2021). This may take the form of a training programme or an individual member from the helping professions, such as a psychologist, social worker or chaplain, who assists in the reintegration process.

With regard to the reintegration programmes offered by the SANDF, the participants noted that, although an effort is being made on the side of the organisation to assist with the reintegration, it is either too little or not present at all:

I mean, the reintegration so-called programme that we had, was a chaplain that spoke to us for half an hour. But there was nothing that you could take back that you could say, I am going to do these steps, you know, when you get home, how do you handle it? Step by step (Participant 2).

You know, what they normally do [to make a reintegration effort after deployments], they will call the psychologists. But I don't think that is enough . Maybe afterwards, they were supposed to have, like maybe a month, or weeks, to prepare us [for the reintegration]. And it is still not happening. Until today. The Defence Force doesn't do that (Participant 6).

The timing of the reintegration services offered is also crucial according to the participants:

[W]hen we arrive [after a deployment] at De Brag (Bloemfontein], we want to go home. Even if you [the helping professional] can talk to me, I don't listen (Participant 6).

[We] had a very small debriefing exercise with only the deployed members, which was more or less a day to get your feelings and try to normalise things. But I'm telling you, of all the people that went, if you go through that programme, the guys will not remember that they went through it. Your head is already at home. If that thing can be presented, while you are down there in the deployment area, before you get home, it will maybe have a better effect (Participant 7).

The efforts from the organisation seemed to be focused mainly on pre-absence training. Participant 9 stated that they (the military members) were given guidelines to assist them when returning from deployment and upon reintegration with their families as part of the resilience training that they received.

When I came back [from deployment], I worked on those guidelines that they gave [during resilience training] to say, if you come back, remember you were not in charge for one year. When you come back, you cannot just forcefully come in, meaning you have to come in progressively. That worked, that actually worked, although there was no formal programme. But the information, I used it and it worked.

Although the reintegration guidelines from the resilience training may be effective, it is the responsibility of the military member to work through the notes and apply it.

Participants who are absent due to training within the borders of South Africa do not receive any form of reintegration. When a course is presented overseas, there is supposed to be a reintegration course but, according to Participant 10, this does not always realise:

They promised us ... before we leave, that this will happen [reintegration programme]. It never happened. And you know what, I'm home for four months now, I'm still not reintegrated in my family (Participant 10).

The participants mentioned that reintegration initiatives should be extended to their families and not only focus on the military member. From the data, it was evident that this was not the case:

No, nothing [no reintegration initiative for the family] (Participant 8).

Discussion and conclusion

Although different military missions may have different effects on the military members and their families (Segal & Segal, 2006), our study found that extended absences pose several challenges, regardless of the reason for the absence (i.e. training or deployments). The common stressor associated with the extended absences seemed to be family separation. Family separation is noted as one of the most significant challenges military members face during combat missions (Kavanagh, 2005) or peacekeeping missions (Dwyer & Gbla, 2022). As was found in the current study, family separation is also a main stressor for extended absence due to training and internal deployments. This is in agreement with Wisecarver et al. (2006) who describe the stress of family separation due to training.

Our study found that military members participate in training or deployment despite the associated challenges. This concurs with the expected utility model of deployment and retention developed by Hosek et al. (2006). This model indicates that most military members prefer some deployment to no deployment (where deployment might include various situations that result in separation from one's family). How often an individual is willing to separate from his or her family will depend on income generated from the separation, time spent at home, and time spent away from home. Participants in our study noted that they participated in training and deployments due to the work requirements for upward mobility in the organisation, financial gain, as well as personal and career development. Most of the participants had been absent from home several times during their careers.

The participants in this study indicated that they often participated in the absences on a voluntary basis, largely for financial gain. Family separation may however have negative financial effects (Hosek et al., 2006), such as increased costs related to childcare due to one parent being absent, increased travel, and communication costs. The financial gains of the absence may not outbalance the unforeseen costs (Behnke et al., 2010). As noted by the model of Hosek et al. (2006), at some point, financial gain from the absence may no longer be a motivating factor to separate from one's family.

Kavanagh (2005) argues that military members remain in the organisation despite the stress and challenges faced due to family separation because they are committed to the organisation. Based on the long military careers of some of our participants, and the number of extended absences over the period of employment, our data also point to committed military members who are serious about their careers. As shown by our data, the commitment of members does not negate the negative effect the extended absences have on their work experiences (such as lower job satisfaction, higher turnover and negatively affecting member wellbeing, to name but a few) (see Behnke et al., 2010; Castro et al., 2001; Wisecarver et al., 2006). The members' commitment to the organisation should be fostered by the organisation by providing better support to retain committed members in the organisation. Organisational support has a direct effect on employee commitment (Baran et al., 2012).

It was also clear from our study that all the phases of the absence are taxing, and they affect members and their families differently at different stages (Lyle, 2006; Pincus et al., 2001). The different challenges experienced by the military members and their families agree with the experiences discussed in the literature review presented earlier. Organisational support should be provided across all the phases of the deployment (prior to, during and after the absence) in accordance with the challenges that can be expected (Doyle & Peterson, 2005). From the current study, it was evident that formal support efforts are mostly concentrated on the period before the absence, in the form of resilience training to military members. In absences due to peacekeeping operations, the resilience training was perceived as valuable, especially in terms of the input it provided regarding the reintegration phase after the deployment (Heinecken, 2020; Heinecken & Wilen, 2021).

From our findings, it seemed that resilience training has some limitations. Firstly, such training is only presented to members who deploy on missions (i.e. peacekeeping missions), and not also to those who will be absent due to training. Secondly, it does not provide support across the different deployment phases. Thirdly, it only includes the military member, and not the family.

Extension of resilience training to all extended absences

Currently, resilience training is presented to members who deploy, rather than those who will be absent due to training. Since the same issues of reintegration are experienced by those who attend military training, it would be valuable if a similar effort is available also to attendees of national and international training efforts that will result in an extended family separation. In fact, besides stressors related to the possibility of injury or death (which may not be experienced during training), concerns are also experienced during training, such as:

• uncertainty about the date of return;

• concerns related to financial matters at home;

• concerns related to children and the spouse coping with the absence;

• possible infidelity; and

• problems experienced during the reintegration phase of the absence (Hosek et al., 2006; Kavanbag, 2005).

Any family separation over an extended period will have consequences for the family unit and the military member. The fact that any family separation - regardless of the reason for the separation - will have severe effects, can be explained by applying the conservation of resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll et al., 2012). Based on the COR theory, people strive to "obtain, retain, foster and protect those things they centrally value" (Hobfoll et al., 2018, p. 104). Family separation in itself is seen as a critical change event that drains the family resources (Behnke et al., 2010). It is therefore imperative that family support be provided to the family during separation, regardless of the reason for such separation.

Extending organisational support efforts to include all the phases of the absence

Some support efforts noted by our participants included resilience training before the absence (if the absence was due to deployment) and a military health professional being available after deployment. Proper support during and after the absence (for both absences, whether training or deployment) was not often offered or was not accessible to members. The results confirm the findings by Heinecken and Wilen (2021) that the SANDF should provide better support during all phases of the absence. It may also be that, despite the services being offered, members do not take part in the support services for various reasons, including the stigma associated with counselling and therapy (Hosek et al., 2006)

To be able to provide comprehensive support, the organisation should ensure that a multi-disciplinary team is available to support the members before, during and after their absence (Kalamdien & Van Dyk, 2009; Sheppard et al., 2010; Sipos et al., 2014). Based on our data, it seemed that support during the absence sometimes took the form of a single social worker or a caring commander. Although support to help the member deal with the challenges while absent is important (i.e. counselling during the absence to cope with the stressors), other aspects, such as being connected to one's family, are also important. During the absence, the separation from one's family is one of the major stressors (Wisecarver et al., 2006). Establishing channels of communication between the military member and the family would be invaluable and would allow the member to remain connected to family members and have a degree of participation in important events back home, albeit virtually.

Support during the reintegration phase should be extensive and comprehensive, and should be provided at the right time. All participants agreed on the need for reintegration programmes, as they were confronted with various conflicting issues on their return. Some participants mentioned that they had to facilitate the process of reintegration as best they could with their knowledge from resilience training (if they had received resilience training).

Reintegration training is critical for workplace reintegration (Sipos et al., 2014), but also for the return to family life (Hosek et al., 2006). Such training will prepare members with the necessary knowledge, skills and attitudes to deal with conflicting situations and to anticipate possible situations and reactions after their return from extended absence. Reintegration training should also provide families with support and access to services after the period of absence. These findings are consistent with studies by Scherrer et al. (2014) and Sipos et al. (2014).

Providing family support