Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Scientia Militaria: South African Journal of Military Studies

On-line version ISSN 2224-0020

Print version ISSN 1022-8136

SM vol.50 n.1 Cape Town 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.5787/50-1-1331

ARTICLES

Role of moral foundations in the nuclear disarmament of South Africa

Arunjana Das

Department of Theological and Religious Studies, Georgetown University

ABSTRACT

South Africa is the only country in the world that successfully acquired a nuclear deterrent capability in the form of six nuclear devices and dismantled them completely. Explanations include strategic reasons, i.e.: the security conditions of the country changed subsequent to the removal of the Soviet threat after the Soviet collapse in 1989 and an end to superpower rivalry in Africa; the increasing isolation of South Africa on account of apartheid; and, pressure from the United States, and concerns about undeclared nuclear technology falling in the hands of a black-led government. While these factors potentially contributed to the eventual dismantlement, the worldwide campaign led by domestic and transnational movements that sought to make moral claims by connecting the cause of anti-apartheid to that of nuclear disarmament likely played a role. In the study reported here, I applied moral foundations theory to the South African case to explore the role played by moral claims in the eventual disarmament.

Introduction

South Africa is the only state to date that has developed nuclear weapons - and subsequently has given them up. Why would states that have explored or made progress towards acquiring nuclear weapons abandon these efforts? It is puzzling that, in spite of having the technological capacity to acquire nuclear weapons, certain states have forfeited this potential military advantage, and reversed course. Potential government inertia against changing or terminating policies that already exist makes such reversal of course even more puzzling. The literature presents a range of explanations for reversal, namely:

• strategic interests (regional and international security, alliances with nuclear weapons states);

• economic interests (costs of the programme, sanctions);

• domestic interests (domestic interest groups, public opinion); and

• norms (international non-proliferation norms).

Although this research could account for a number of cases, it left unexplained important cases, thereby rendering contemporary opportunities for nuclear disarmament under-exploited.

I found that moral claims, as a type of normative claims, could account for nuclear reversal by South Africa. Scholarly and anecdotal evidence in other areas shows that moral claims have an effect.439 Such claims have been a part of the discourse surrounding nuclear weapons for a long time, and there is evidence of their existence in a few states that engaged in reversal. International and regional legal regimes prohibiting entire classes of weapons, such as landmines, cluster munitions, and chemical and biological weapons, involved the use of moral claims.440 Although nuclear weapons are a different class of weapons, we can learn lessons from how moral claims contributed to state action in such prohibitory regimes. This research has policy significance, since if we find moral claims to be effective, there are direct implications for addressing future proliferation threats.

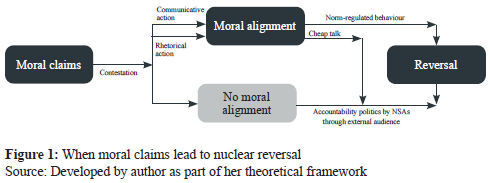

I apply moral foundations theory (MFT) from the literature on moral philosophy and social psychology to explain how moral claims contributed to conditions that led to nuclear reversal by South Africa. I argue that moral claims can contribute to creating circumstances leading to nuclear reversal under the following conditions: when there is increased moral alignment between the state and reversal advocates, or in the absence of moral alignment, when advocates engage in accountability or leverage politics by appealing to an external authority or audience, or the domestic electorate. I conceptualise 'nuclear reversal' as a state moving from a higher to a lower stage in the proliferation process.441 'Moral claims' are conceptualised as value-based statements, demands, or assessments with a claim to universal validity.442

I use MFT to assess how various actors (the state and transnational activists) use moral foundations in their discourses in the South African case and whether the theory could potentially explain the South African reversal. For the state discourse, I reviewed official statements made by the President, Defence Minister, and ambassadors to the United Nations (UN) and the United States regarding the position of the state on nuclear weapons. In terms of the international discourse, I looked at annual reports made in the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) General Conferences and resolutions at the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). For the non-state discourse, I looked at the following national and transnational activists (TNAs): the African National Congress (ANC), the Anti-Apartheid Movement (AAM), and the World Campaign against Military and Nuclear Collaboration with South Africa.443 There are several other major TNAs that were active in the South African disarmament case, such as the Catholic Church, Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF), and the World Council of Churches, among others. I, however, chose only the ANC, the AAM, and the World Campaign for the following reasons:

• they played a pivotal role in the campaign to denuclearise South Africa, and at various times, created coalitions with other TNAs, including the ones mentioned above; and

• their statements and other textual material are archived and accessible online, thereby enabling the researcher to conduct a systematic textual analysis.

Explanations for nuclear reversal

Most theories offered for explaining nuclear proliferation and reversal fall within one of the three models offered by Sagan (1996): security, domestic politics, and norms.444Others conducting detailed individual case-studies have talked about multiple factors which together cause reversal, such as a change in security threats, domestic concerns, technological challenges, regime-type, pressure from the United States and the UN, and sensitive nuclear co-operation.445 Sagan (1996) provides the following explanations for proliferation or reversal:

• a change in security threats and conditions;

• domestic politics and interests making it politically expedient to either pursue or reverse a programme;

• norms of prestige and status associated with nuclear weapons (for proliferation) and non-proliferation norms informing reversal decisions.

These three models align with the realist, liberal, and constructivist schools in the field of international relations(IR).

Among security justifications, most realist explanations, such as those offered by Paul (2000) and Monteiro and Debs (2014) - - argue that a change in international or regional security conditions that caused the state to pursue nuclear weapons in the first place, also encourage reversal once the security threat is gone.446 Others posit that security guarantees from allies, and the threat of punishment, such as preventive strikes, and external threats or pressures from the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union, explain reversal.447 Mattiacci and Jones (2016), on the contrary, argue that it is nuclear latency that increases the likelihood of reversal, since it enables states to engage in nuclear-hedging.448

Liberal perspectives offer economic sanctions, cost overruns, inefficiencies associated with neo-patrimonial regimes, and domestic interest groups as reasons for reversal.449Some argue that weapons programmes in neo-patrimonial regimes with unchecked leaders or politically influential domestic groups are more susceptible to cost overruns and inefficiencies.450 Solingen (1994) argues that economic liberalisation can drive reversal decisions, especially if domestic groups benefit in the form of debt relief, technology transfer, and investments from the international community.451 Rublee (2009), however, contends that, although domestic coalitions can contribute to reversal, there are normative components to liberalising coalitions, which neoliberals do not admit.452Drawing from social psychology, Rublee (2008) argues that norms associated with the international non-proliferation regime exert a strong influence on nuclear reversal.453

Although these perspectives can explain some reversal cases adequately, they do not persuasively explain important cases that could have implications for future nuclear threats. In the cases of South Africa, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and Iran, for example, the conventional wisdom positing security-based arguments is contested. 454 Theories suggest that South Africa dismantled its nuclear weapons after its security conditions changed subsequent to the removal of the Soviet threat after the collapse of the USSR in 1989 and an end to superpower rivalry in Africa.455 Other explanations include:

• the increasing isolation of South Africa on account of apartheid;

• the desire of the country to be part of the international community;

• pressure from the United States government on South Africa's apartheid government to join the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT); and

• concerns about undeclared nuclear material and technology falling in the hands of a black-led government.456

While these factors potentially contributed to the eventual dismantlement of the South African nuclear weapons programme , normative considerations also played a role. In an interview, President FW de Klerk said that one of the primary reasons behind his decision to dismantle the program was that nuclear weapons would "be morally indefensible to use" and "it was the right thing to do" to dismantle the programme.457While this could be categorised as an ex post facto moral justification of dismantlement motivated by other considerations, i.e. rhetorical action, it is also true that domestic and transnational activists tied the anti-apartheid cause to that of nuclear disarmament and brought pressure to bear on the international community and the apartheid government.458The explanations did not look at how such moral claims might have influenced the apartheid government's decision of dismantlement, either through domestic or international pressure. Intondi (2015) shows the vital role that black activists in America played in connecting nuclear disarmament to the struggle for racial equality in global liberation movements, and made the moral claim that the fight against the nuclear arms race, racism and colonialism was a fight for the human race.459

Moral claims are not necessarily in support of nuclear reversal. Several states and non-state actors (NSAs) have used moral claims invoking national security and the protection of citizens to justify nuclear aspiration and deterrence. Most TNAs, however, have used moral justifications in support of nuclear reversal and disarmament.460

Public and foreign policy studies find that alignment in certain aspects of moral claims between government and advocates may correspond with greater responsiveness in policy.461 Others have found that when norms are presented in language that refers to existing norms, draws analogies or frames issues to appeal to policy gatekeepers, they are more effective in facilitating policy responses.462 This insight has implications for studying the conditions under which moral claims can facilitate policy responses.

Moral claims and moral discourse

The objective of a moral discourse is to arrive at common moral claims. Such commonality is evidenced by moral alignment as manifested in claims made.463 The logic underpinning this process can be either that of argumentation (i.e. communicative action, the value-based incentive of searching for the truth) or the logic of consequences (i.e. rhetorical action, speech acts motivated by strategic incentives). Most realist scholars argue that states use moral claims and moral discourse as rhetorical action.

Constructivists do not only deny this, but they also argue that communicative action could happen under certain conditions, and might influence state action.464 There is, however, limited theorisation in IR on the nature of moral claims, and their impact on policy.

Moral foundations theory (MFT) offers a helpful taxonomy to address this. MFT posits five foundational concerns that underline the innate value systems of human beings, and constitute moral language: caring for and protecting others from harm, maintaining fairness and reciprocity, in-group loyalty, respecting authority, and protecting one's purity and sanctity.465 Although MFT has not been used to study nuclear reversal and disarmament yet, scholars have used it to study moral claims in the use of nuclear weapons, for example, work by Rathbun and Stein (2020), and in other diverse issue areas, including public health, climate change, same-sex marriage, and stem cell research.466Greater alignment of moral foundations between state and advocates corresponds with more responsiveness in policy, while misalignment in moral foundations corresponds with conflict and a delayed response to advocacy.467 I, hence, expected to find greater policy responsiveness in terms of policies undertaken towards reversal when there is greater moral alignment between state and reversal advocates. This is however expected only when the underlying rationality is communicative in nature.

Scholars argue that, when norms are presented in language that refers to existing norms, draws analogies, or frames issues to appeal to local agents or policy gatekeepers, they are more likely to be adopted.468 Keck and Sikkink (2004) argue that TNAs often work through actors with leverage or influence on state policymaking ("leverage politics"), and use language to create symbols and new issues through interpretation and reinterpretation of existing issues ("symbolic politics"). Thus, if reversal advocates use moral foundations in ways that relate to or draw analogies with existing norms, or frame it in a way that enhances the authority of existing state institutions, they are more likely to be aligned with moral foundations of the state.469

Alignment is also more likely if claim-making actors are perceived to have moral authority, credibility or legitimacy.470 The concept of authority is used to justify various political actors, including states, international organisations and other NSAs.471 Sources of such authority are:

• policy partiality or expertise (e.g. "knowledge brokers", such as epistemic communities, or organisations that engage in information politics472);

• impartiality or neutrality (e.g. volunteer organisations, such as the Red Cross); and

• normative superiority or representation of ethical and principled ideas (e.g. certain religious or humanitarian entities).473

Moral alignment is, therefore, more likely if reversal advocates are perceived to have authority on account of being knowledge brokers, impartial, or possessing normative superiority.474

Moral alignment can sometimes be the result of rhetorical action on the part of the state, i.e. states engage in "cheap talk".475 Moral foundations can align in this case without states actually intending to follow through on the commitments they articulate in their rhetoric. In this case, however, there is "rhetorical entrapment"476 of the state, which TNAs could control by holding the state accountable, i.e. engaging in accountability politics.477 Quissell (2017) found that accountability politics, or venue shopping, through the court system or elections could facilitate policy change even in the absence of moral alignment. When moral alignment does not occur between the state and reversal advocates, reversal may still occur if advocates hold the state accountable by activating an external authority or audience, which could be domestic or international courts, or a domestic voter base.478 Hence, in the case of moral misalignment between the state and reversal advocates, reversal may still occur if advocates engage in accountability politics through an external authority or audience (see Figure 1).

Theoretical framework

Figure 1 below outlines the process of moral discourse that occurs at domestic and international levels. At a domestic level, the nuclear aspiring or reversing state and NSAs (including domestic NSAs and TNAs) engage in a moral discourse in which they make moral claims. Similarly, at an international level, the state engages in moral claim-making with other states and TNAs. Domestic NSAs and TNAs seek to influence the domestic policies and international negotiating positions of the state. State negotiators, in turn, persuaded at international level, attempt to persuade domestic audiences. The external authority or audience could be an active voter base, or a national or international court system, which NSAs activate. Many a time, TNAs form coalitions with domestic NSAs to persuade the state at domestic and international level to take steps towards nuclear reversal. This was evident in the South African case as well. The reversal decision by a state therefore could be influenced by this suasion either at domestic or at international level.

The theoretical framework depicted in Figure 1 provides an analytical tool to understand the South African case of denuclearisation where reversal occurred in the presence of moral claims. The case is complicated however by the fact that the nuclear weapons programme was conducted in secret, and the state followed a policy of nuclear opacity and strategic uncertainty when it came to taking a position on nuclearisation. Since some cases of reversal occurred in the absence of evidence of moral claims, they are neither necessary nor sufficient for reversal. Instead, I propose that they could bring about conditions that may lead to nuclear reversal.

Research design

I hypothesize that nuclear reversal could occur in the case of any of these conditions:

• when moral foundations align between state and reversal advocates, and they engage in communicative action;

• when reversal advocates engage in accountability politics under the circumstances when moral foundations align, but the prevailing rationality is rhetorical as opposed to communicative; or

• when reversal advocates engage in accountability politics in the absence of moral alignment.

Moral alignment is more likely when reversal advocates use moral foundations in ways that relate to or draw analogies with existing norms, underscore their authority, or buttress the authority of existing state institutions. In the study reported here, I tested this against the null hypothesis that moral claims do not contribute to nuclear reversal.

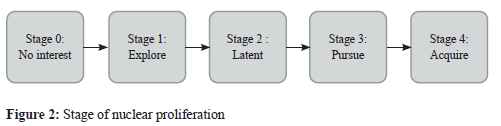

Literature on nuclear pursuit and reversal conceptualises the state proliferation process either as a dichotomous variable (i.e. the state is in possession of nuclear weapons versus not in possession) or on a continuum with various stages and "degrees of nuclearness".479Levite (2002) conceptualises reversal as the slowing down or rollback of a weapons programme.480 Singh and Way (2004) divide the continuum of nuclearness into four stages: no interest, explore , pursue, and acquire .481 I adopted their conceptualisation because it offers a nuanced approach to differentiate between proliferation stages and reversals observed empirically. I also added another stage to it: nuclear latency, which I situate between the stages of Explore and Pursue. ) In the Latent stage, which I call stage 2, states do not possess nuclear weapons and are not actively pursuing nuclear weapons, but possess the technological capability to acquire them quickly.482 I conceptualise the nuclear weapons proliferation process in the following stages:

Reversal is a type of nuclear transition during which a state moves to a lower stage from a higher stage.483 The independent variable is moral claims operationalised in terms of moral foundations according to the Moral Foundations Dictionary (MFD).484

Methods

South Africa established the Atomic Energy Board in 1948 through the Atomic Energy Act (No. 35 of 1948, as amended by Acts Nos. 8/ 1950 and 77/ 1962) to regulate the domestic uranium industry. In co-operation with the United States, under the Atoms for Peace programme, the South African government established the Pelindaba site and explored uranium enrichment technologies, including acquiring highly enriched uranium (HEU), during the 1960s.485 On 20 July 1970, Prime Minister John Vorster announced that South Africa had designed a unique process to produce HEU.486 The statements made during this period by state officials and reversal advocates frequently showed evidence of moral foundations. This became even more evident during the years when the issue of apartheid was strategically tied with the issue of denuclearisation by South Africa. I analysed whether the alignment or misalignment of moral foundations over the said time could explain this nuclear reversal. To identify moral alignment or a lack thereof, I looked for evidence of moral foundations in claims made by the South African state and reversal advocates, such as state actors in the international community and transnational non-state actors. This was a qualitative analysis that looked at where moral foundations were being drawn from, how they were used by various actors, whether alignment was happening, and to what degree. I then identified whether the actions taken by the South African state with regard to its nuclear weapons programme corresponded to this alignment or lack of alignment as posited by my theoretical framework.

I drew from six major moral foundations proposed under the auspices of MFT and assessed the content of the primary texts qualitatively for the presence of each of the foundations. I also drew from the MFD to code the content of the texts. Please note that, although most of the earlier research using MFT and MFD conducted quantitative analyses of content, this approach was not useful for the study on which this article reports because of the incomplete nature of archival material and the unavailability of relevant documents about the secret nuclear weapons programme. Most of these were destroyed before their existence was publicly acknowledged by President De Klerk.487 In order to conduct a qualitative analysis of the texts, I looked for language that emphasises the following moral foundations:

• Care or harm: Language that emphasises the need to care for and protect others from harm - with underlying virtues, such as kindness, gentleness and nurturing.

• Fairness or cheating: Language related to ideas ofjustice, rights, equality, proportionality, and autonomy.

• Loyalty or betrayal: Language related to communitarian ideas, coalitions, patriotism, group values, etc.

• Authority or subversion: Language related to hierarchy, leadership and followership, deference and subordination to authority, respect for traditions, etc.

• Sanctity or degradation: Language related to culture, rituals, religious purity, holiness, righteousness or moral ways.

• Liberty or oppression (new addition): Language emphasising experiencing feelings of oppression, persecution or domination.

Findings

As per Figure 2, the South African trajectory of nuclear weapons behaviour can be categorised into the following stages: Stage 0: No interest, Stage 1: Explore, Stage 3: Pursue, Stage 4: Acquire; Stage 0: No interest . Inclusion of the last stage in the trajectory as Stage 0 indicates South Africa's decision to dismantle its nuclear weapons programme, thereby, moving the country back to Stage 0 - No Interest. For this article, I was interested only in the three phases of explore, pursue, and acquire. During these phases, one can see an evolution in the foundations from which both the state and reversal advocates drew. In terms of alignment of foundations, there is greater alignment during the phases of explore and acquire, than in pursue. Stage 4 is guided by a rhetorical rationality, although the South African state and the reversal advocates were drawing from the same foundations and used them in similar ways, South Africa was lodged firmly in the phase of acquire. A few similarities and differences are also seen in how TNAs used moral foundations in advocating for South African denuclearisation and how the international community used the foundations in international for a, such as the IAEA, the UNSC (UN Security Council), and the UNGA.

South Africa was one of the founding members of the IAEA, and an active and vital supplier of uranium to the world market for production of nuclear energy for peaceful purposes. It had bilateral agreements with the United States, the United Kingdom and Israel for uranium supply, and was the beneficiary of nuclear fuel and technology from the United States for its domestic reactors used for research and for production of medical isotopes.488 In the mid- to late 1960s, South Africa started exploring uranium enrichment technology towards producing HEU. In 1970, South Africa announced the construction of the Y-plant at Valindaba for the production of enriched uranium, ostensibly for peaceful use.489 Between 1969 and 1979, the South African Atomic Energy Board (AEB), which later became the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), conducted all research and development (R&D) work connected to the South African Peaceful Nuclear Explosion (PNE) device programme.490 When the non-proliferation treaty (NPT) came into effect in 1970, and South Africa refused to join those who had become party to the treaty, it raised the suspicions of the international community.491 South Africa, however, maintained the position that the NPT was an inherently discriminatory treaty that divided the world into nuclear haves and nuclear have-nots, and provided that as a reason behind the refusal to join, which was similar to the position of India on the NPT. 492

Between 1970 and 1978, South Africa actively engaged in the production of HEU along with secret R&D work on a peaceful nuclear explosive, studies on implosion devices and gun-type devices.493 In 1979, this work led to the production of, what was called, a "non-deliverable demonstration device," whose primary purpose was to demonstrate the South African nuclear weapons capability in an underground test.494

While the decision to pursue a secret nuclear deterrent capability could have been taken in 1974, we find clearer evidence of this after 1977.495 In 1978, after PW Botha became president, he gave orders to acquire a nuclear deterrent capability.496 Between 1978 and 1989, South Africa secretly pursued a nuclear weapons programme, and built six weapons.497 With the election of President De Klerk in 1989, a decision was however made to terminate the nuclear weapons programme. In February 1990, the president gave the order to dismantle the six nuclear devices that had already been developed and the seventh device that was incomplete. On 10 July 1990, South Africa acceded to the NPT. By April 1993, South Africa opened its facilities for inspection by the IAEA after the nuclear weapons and the associated technologies had been dismantled and related documentation been destroyed. 498

In 1993, in a joint parliamentary address, President De Klerk announced that South Africa had built six nuclear weapons in order to have a nuclear deterrent capability and had dismantled the programme before joining the NPT as a non-nuclear weapon state (NNWS).499

Stage 1: Explore (1970-1978)500

Although South Africa was an active member of the IAEA as a supplier of uranium and a recipient of nuclear technology for its domestic research and medical reactors, its membership became tenuous as the international community got increasingly suspicious of its nuclear intentions between 1970 and 1978, and called for its denuclearisation.501During this period, several resolutions were adopted in the UNSC and the UNGA that called for a range of measures against the apartheid regime of South Africa, including cessation of cultural, economic and military collaboration with the regime.502 Certain countries, such as the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Germany and Israel, continued their military collaboration, including nuclear collaboration, in violation of a UN arms embargo against South Africa, at which the UNGA resolutions expressed alarm.503

In an UNGA resolution on apartheid adopted in 1974, nuclear collaboration is explicitly mentioned as one of the tools to pressure the racist regime economically.504 There was, however, no explicit mention of a South African nuclear weapons programme. This changed in 1975, when the resolution explicitly called for governments to cease all nuclear co-operation with South Africa and stop delivering any nuclear technology that might enable the South African regime to acquire nuclear weapons.505 UNGA annual conferences between 1976 and 1978 saw a number of resolutions passed condemning the racist regime in South Africa and laying out various measures, including denuclearisation of South Africa, cessation of all diplomatic, economic and military co-operation with the racist regime, and support of political prisoners and anti-apartheid activists in South Africa and around the world.506

UNGA resolutions connecting cessation of nuclear collaboration with South Africa with that of pressuring the racist regime also found mention in the IAEA General Conference annual reports.507 Until 1976, South Africa was mentioned in the IAEA General Conference annual reports only in the context of its existing nuclear agreements and presence of research reactors for production of medical isotopes.508 At the IAEA General Conference held in 1975, the annual report submitted contained only two references to South Africa in the body of the text.509 The IAEA Annual Report for 1976 mentioned apartheid for the first time when the General Conference argued that having the apartheid regime as the member for the area of Africa, was inappropriate and unacceptable.510

The General Conference also requested the Board of Governors to review the annual designation of the Republic of South Africa as the Member for the area of Africa taking due account of the inappropriateness and unacceptability of the apartheid regime of the Republic of South Africa as the representative of the area of Africa and requested the Board to submit a report to the General Conference at its twenty-first regular session.511

The 1977 IAEA annual report mentioned the call for the denuclearisation of Africa made in the 1976 UNGA annual conference.512 At the same meeting, the board replaced South Africa with Egypt as the "Member State in Africa most advanced in the technology of atomic energy, including the production of source materials".513 The 1978 IAEA GC annual report continued to mention the UNGA resolutions calling for cessation of nuclear co-operation with South Africa and its denuclearisation.514 In 1979, South Africa was expelled from the General Conference of the Agency held in New Delhi, as a result of sustained effort made by G-77 members in the IAEA.515

During this period, although UNGA resolutions were articulating their opposition to the racist regime in South Africa using moral foundations, in 1974 they explicitly called for the ceasing of nuclear collaboration of states with South Africa.516 Between 1974 and 1978, the foundations that were prominently used were care and authority.

For example, the 1975 UNGA resolution argues that the UN

Condemns the racist regime of South Africa for its policies and practices of apartheid, which are a crime against humanity, for its persistent and flagrant violations of the principles enshrined in the Charter of the United Nations and for its continued defiance of the resolutions of the General Assembly and the Security Council ... Denounces the maneuvers of the racist regime of South Africa, which are designed primarily to perpetuate and obtain acquiescence in its abhorrent apartheid policies to deceive world opinion, to counter international isolation, to hinder assistance to the national liberation movements by the international community and to consolidate white minority rule in South Africa.517

It goes on to say that it -

[Declares] that the racist regime of South Africa, by its resort to brutal oppression against the great majority of the people of the country and their national liberation movements, bears full responsibility for precipitating violent conflicts, which is bound to occur if the situation remains unchanged. It recognizes that the international community must take firm action against the racist regime of South Africa in order to avert any suffering in the course of the struggle of the South African people for freedom.518

Similarly, the discourse from the ANC and AAM during this period drew significantly from the care, harm,fairness, and liberty foundations. The use of the authority foundation was less pronounced than in UNGA resolutions and IAEA GC annual reports.

For example, the ANC in the January 1977 issue of its monthly official journal, Sechaba, says:

The minority regime is so savagely repressive that ordinary people are called upon to show extraordinary heroism in making their demands for the most elementary human rights. It has always been so for the masses. Time and again they have shown more courage than it has taken for many a nation to gain independence, in other parts, at other times.519

It goes on to say:

The freedom we are fighting for is different. It means one South Africa for all who live in it. It means power to the people. It means sharing the country's wealth by taking over the mines and great monopoly industries for the benefit of the people. It means the land shall be shared among those who work it. It means an end to bloodshed and war.520

State actors, as part of the international community, and TNAs used the care foundation in similar ways, which manifested itself in language that emphasised the connection between denuclearisation and human development.521 For example, the UNGA Resolutions passed between 1976 and 1978 asked for the implementation of the Declaration of Denuclearization adopted by the Organization for African Unity and called for effective measures towards implementing the objectives of the 70s as a disarmament decade.522 Part of this movement, the resolution argued, was for South Africa and other states with nuclear weapons to disarm and dismantle said weapons, and use the funds freed up for creating better living conditions for and development of people. 523

It calls upon its member states to "promote disarmament negotiations and to ensure that the human and material resources freed by disarmament are used to promote economic and social development, particularly, in developing countries".524

The care foundation also frequently manifested itself in language that called for a halt of military and nuclear collaboration with the apartheid regime since such collaboration would further strengthen the defences and economy of the apartheid regime, which, in turn, was conducting brutality against the South African people.525

The ANC and the AAM used the liberty foundation more prominently than the IAEA GC and UNGA resolutions. It manifested itself in language that emphasised the domination of indigenous South Africans by the racist regime, and the latter's attempt at introducing nuclear weapons to the African continent as an effort to terrorise and dominate African people.

In a report released in 1976, the AAM says:

South Africa has highly sophisticated military equipment, including modern fighters, missiles and rockets. It has developed various nerve gases and a whole range of ammunition. It is constantly in search of the most modern equipment, which is also highly expensive. As the feeling of insecurity increases, it responds by purchasing more and better weapons, hoping that this will be adequate to intimidate and deter Africans internally, as well as neighbouring African States which may consider supporting the liberation struggle. 526

It goes on to say:

It has always been known that all the major western powers have collaborated closely with South Africa in developing its nuclear technology and plants ... South Africa has refused to sign the Non-Proliferation Treaty and is now an incipient nuclear power; the grave danger which an apartheid nuclear bomb presents to Africa and the world is obvious.527

While IAEA GC and UNGA both emphasised the authority of the UN arms embargo, they repeatedly emphasised its violation by certain member countries, most prominently, the United States, the United Kingdom, France and Germany.528

The authority foundation was less pronounced in claims made by TNAs, but manifested itself in language that emphasised the fact that South African people should have self-determination and autonomy over their political and economic futures.529 This language also touches upon the fairness foundation.

In the April 1978 issue of the Sechaba, the ANC says:

The world should be aware of the fascist response to the twin problems of political unrest and economic instability. These measures which deepen the national oppression of the African people, depriving us of 'citizenship' in the land of our birth, and attack the few remaining rights of all nationally oppressed working people, make us aware of the need to combine more than ever before, the two aspects of our struggle: national liberation and class struggle.530

During this time, the official state communications from the South African government maintained that its nuclear programme was peaceful in nature.531 In response to international suspicions regarding its refusal to sign the NPT, Ambassador Ampie Roux, the South African delegate to the IAEA, argued that states were "understandably reluctant to surrender, almost irrevocably, long-held sovereign rights without having precise details of all the implications".532 The claims that it made domestically and with international actors during this time featured largely the foundations of fairness and authority. 533

On 24 August 1977, in a speech at Congress of the National Party of Cape Province, Prime Minister Vorster accused the IAEA and the US for not respecting their commitments to South Africa. He said:

The IAEA, which has a responsibility of ensuring that the obligations of the NPT are carried out by the signatories, must inspire confidence with all the parties to the Treaty and only then can it fulfill its functions satisfactorily ... Furthermore, countries like the USA have not honored the commitments they have entered into bilaterally. 534

Most of the international condemnation of the apartheid regime occurred as a result of active campaigning by the G-77, and domestic and transnational non-state actors, such as the ANC and the AAM. This international opprobrium led to a range of measures intended to put pressure on the regime, including UN sanctions, arms and trade embargoes, and cultural, educational and sport boycotts. Some of these measures were reflected in the IAEA, which adopted several resolutions against South Africa and sought to suspend its membership. In 1977, due to suspicions expressed by the United States regarding its nuclear facility in the Kalahari Desert, South Africa denied that it was a test facility, rebuking it with the need to maintain trust and goodwill in the international community that was committed to pursuing nuclear energy for peaceful use. 535 In doing so, South Africa drew from the foundations of fairness and loyalty. Although South Africa dismantled the reactor, a year later, after becoming prime minister in 1978, Prime Minister PW Botha provided explicit orders for South Africa to acquire a nuclear deterrent capability. 536

It is to be noted that during this time, the South African state and the reversal advocates were mostly drawing from different moral foundations. Whereas the apartheid regime drew from largely the foundations of fairness and authority, the reversal advocates, including state and non-state actors, drew from care, authority, and liberty. Although both sides were drawing from the authority foundation, they were doing so in different ways and within different contexts. There is, hence, scarce moral alignment that is evident qualitatively in their claims. This corresponds with the lack of policy responsiveness displayed by the apartheid regime to the claims made by reversal advocates. The regime, in fact, went ahead with the production of six nuclear devices over the next few years.537

Stage 2: Pursue (1978-1979)

Throughout Stages 1 and 2, as the international community became increasingly suspicious of the South African nuclear programme, the state engaged in denials of such suspicions in international fora and through letters and communications to various other states, such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union.538

The foundations that were used frequently during this time were: fairness and authority. The fairness foundation manifested itself in language that emphasised the right of South Africa to pursue nuclear energy for peaceful use, and the authority foundation manifested itself in language that emphasised South Africa as a sovereign entity and the regime being legitimate with autonomy and authority over its nuclear future that its detractors ought to respect.539

For example, the 1979 Plenary Meeting of the IAEA General Conference held in New Delhi, summarised the response of the South African delegation on the IAEA's decision to expel South Africa from the IAEA board of governors:

Mr. DE VILLIERS (South Africa) considered the General Committee's decision wholly illegal and without precedent in the annals of the Agency. The credentials of the South African delegation were strictly in conformity with the Agency's Statute and the Rules of Procedure of the General Conference, as all past sessions of the General Conference had recognized. They had been issued by the same authorities which had issued the credentials of the South African delegations to the past 22 annual sessions of the General Conference. It could by no stretch of the imagination be argued that those credentials, at the 23rd session, were not in order. The proposal before the General Conference was a blatantly unconstitutional action, politically conceived, to prevent a Member of the Agency - a technical organization - from exercising its constitutional right to participate in the deliberations of the Conference.540

The UNGA resolutions adopted during this time explicitly accused South Africa of pursuing a secret nuclear weapons programme and called for its denuclearisation and exhortation to put all its nuclear facilities under comprehensive IAEA safeguards.541The 1979 IAEA GC referred to said UNGA resolutions and called for South Africa to submit its facilities to inspection by the IAEA.542 It also provided information to the UN Secretary General on preparing a comprehensive report on South African plans and capabilities in the nuclear field.

During this time, statements on the South African nuclear programme in IAEA GC and UNGA resolutions drew from the foundations of liberty in addition to care and fairness.543

Similarly, statements from the ANC and the AAM drew from the three foundations of care, harm, fairness, and liberty or domination, with the most prominently used foundation being that of liberty or domination and care or harm. 544

In the March 1979 edition of Sechaba, the ANC says:

The ANC stands for national liberation from colonial and racist oppression in Apartheid South Africa, so-called historic, geographic, and ethnic claims of whatever kind or "tribal" affinity cannot dissuade us from that goal. We believe that each African country has to be decolonized within the confines of established boundaries and the oppressed people have a right not only to wage a struggle to assert their right of national self-determination and independence, but also to freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social, and cultural development to ensure permanent sovereignty over their natural wealth and resources.545

It goes on to say:

That free South Africa must therefore redefine black producer or rather, since we the people shall govern, since we shall have through our own struggle, placed ourselves in the position of makers of history and policy and no longer objects, we shall redefine our position.546

Documents from the AAM and secondary sources show that there was an explicit attempt to connect the issue of apartheid with that of nuclear disarmament as a struggle for human rights.547 Campaigns that connected nuclear disarmament with that of divestment and stopping financial aid were also made explicitly.548 This was reflected in the statements made by ANC leaders in joint ANC-AAM conferences.549

The AAM was especially active in campaigning domestically in Britain against the British government collaborating with South Africa by providing arms and spare parts. In 1979, the AAM started the World Campaign against Military and Nuclear Collaboration with South Africa, which monitored the violations by Western countries against the arms embargo and submitted evidence to the special UN committee set up to monitor the embargo.550

During this time, the official state communications from the South African government continued maintaining that its nuclear programme was peaceful in nature, emphasising the foundations offairness and authority (as a free nation with autonomy over its future) in its discourse.551

It is to be noted that here again, although both the South African state and the reversal advocates were drawing from the fairness and authority foundations, they were doing so in different ways and within different contexts. Whereas the South African state articulated fairness as their right to pursue their nuclear future, and the authority and autonomy as a sovereign state to do so, the reversal advocates articulated fairness as the subordinated and dominated people of South Africa to be given their legitimate right to self-determination, and not be terrorised by a racist regime with nuclear weapons. This stage too, hence, shows less alignment than what a quantitative analysis would have suggested. There is, hence, scarce moral alignment that is evident qualitatively in their claims. This corresponds with a lack of policy responsiveness displayed by the apartheid regime to the claims made by reversal advocates.

As evidenced by the UNGA resolutions in 1978 and 1979, during this time, the South African state was isolated by the international community, but was still supported by the United States, the United Kingdom and Israel.552 These countries also voted against every UNGA resolution condemning the apartheid regime. Meanwhile, the apartheid regime continued ignoring calls by the IAEA and the UNGA to come clean regarding its nuclear programme and put all its reactors under complete IAEA safeguards. 553

Stage 4: Acquire (1980-1989)

By 1979, South Africa had developed the first nuclear device, and by 1989, it had developed six nuclear devices.554 During this time, as the opposition from the international community to the apartheid regime became fiercer, it resulted in the economic, military, cultural, and diplomatic isolation of the apartheid regime as the international community started a campaign that included sanctions, divestment by major businesses, and a cultural boycott. 555

The UNGA resolutions adopted during this time explicitly accused South Africa of pursuing a secret nuclear weapons programme, called for its denuclearisation and exhortation to put all its nuclear facilities under comprehensive IAEA safeguards, and openly condemned the United States, the United Kingdom and Northern Ireland and France for continuing to supply South Africa with nuclear technology.556

The 1980 UNGA resolutions on South Africa, which were also mentioned in the 1980 IAEA GC annual report, called for all UN agencies to ensure the participation in their various conferences and meetings of liberation movements in South Africa recognised by the Organization of African Unity.557

During this time, statements in the IAEA and resolutions in UNGA on the South African nuclear programme drew from the foundations of liberty or domination and loyalty or betrayal in addition to care or harm, fairness, and authority.558

Similarly, statements from the ANC and AAM drew from the three foundations of care, fairness and liberty, with the foundation used most prominently being that of liberty.559

In the documents cited above, the liberty foundation manifested in the usage of language that included recognition and support of the South African liberation movement against the racist regime. It also called for other states, businesses, and international organisations to support the same, provide assistance to refugees, especially students and children, from South Africa, provide support for the political prisoners incarcerated by the apartheid regime, and invited leaders from liberation movements to conferences and meetings of international fora.

The domination foundation (connected to the liberty foundation) manifested in language that articulated the South African nuclear weapons capability as a tool of blackmail used by the apartheid regime.560

Stressing the need to preserve peace and security in Africa by ensuring that the continent is a nuclear-weapon free zone, . condemns the massive buildup of South Africa's military machine, in particular, its frenzied acquisition of nuclear weapon capability for repressive and aggressive purposes and as an instrument of blackmail.561

Similar references articulated the danger posed by military, including nuclear, arms acquisition by the South African regime as a threat to world peace. The statement below from the 1985 UNGA resolution (and subsequent UNGA resolutions until 1989) also drew from the loyalty or betrayal foundation by articulating the nuclear acquisition of the apartheid regime as a threat to the global community as a whole.562

[A]cumulation of armaments and the acquisition of armaments technology by racist regimes as well as their possible acquisition of nuclear weapons, presented a challenging obstacle to the world community, faced with the urgent need to disarm.563

The fairness foundation was drawn from in references that included condemnation of the exploitation of uranium resources in Namibia by the racist regime and its allies in the form of the United States, the United Kingdom and Northern Ireland, and France.564 The authority foundation appeared in references that framed South Africa to be in violation of international law and the provisions of the UN Charter, and wilfully ignoring IAEA requests to put its nuclear facilities under full safeguards.565

Statements from the ANC and the AAM continued to emphasise the connection between the intentions of the racist regime to terrorise the South African people and her neighbours and acquiring a nuclear deterrent capability, for which, the ANC and the AAM argued, western nations were her allies.566

At the launch of the UN Special Committee against Apartheid, Oliver Tambo, an ANC leader, talked about the responsibility of the free world to support South Africans in their liberation struggle. 567

These communications continued emphasising the foundations of liberty, care, fairness, and authority with liberty and care being the most dominant ones followed by authority of international law and international organisations such as the UN and the IAEA.

The South African state official documents continued emphasising the foundations of fairness and authority, but also increasingly drew from the loyalty or betrayal foundation. The latter manifested itself in language used by the South African state accusing the ANC (and the United Democratic Front) of being traitors and terrorists for its attempts to destabilise the regime, especially after the bombing of the Koeberg reactor by the ANC.568

Similar language was used by the state to discredit liberation movements in South Africa and its neighbours as attempts by the Soviet Union to establish its sphere of influence in Southern Africa.569

From the mid-1980s to 1989, as there was increasing pressure on the South African state to sign and ratify the NPT as a Non-Nuclear Weapons State (NNWS), it articulated its interest in joining at an opportune time, and the fact that it was conforming to the goals and tenets of the NPT in spirit.570 The fairness foundation was manifested in language that stressed the continued right of South Africa to decide its nuclear future, and the authority foundation manifested in South Africa, at least rhetorically, agreeing to abide by the authority of the IAEA, NPT, and UNGA.571

It met with IAEA officials in 1984 and 1985 to negotiate the technical details of a potential safeguards agreement without explicitly committing to opening up its facilities for IAEA inspection in the near future.572

As declassified documents show, during this time, the top South African leadership was considering the ramifications of the potential accession of South Africa to the NPT.573The Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA) argued for a "balanced approach to the NPT", wherein it states that maintaining a nuclear deterrent for the next few years, as suggested by Armscor, its central arms production and procurement agency in charge of its nuclear weapons programme, was not compatible with the domestic economic, social, and political requirements of South Africa. According to the DFA, continuing the nuclear weapons programme could be justified only on three separate grounds:

• certain future use, which would cause tremendous damage in terms of radioactive fallout;

• maintaining deterrence, which would increase South African global political, economic and diplomatic isolation; and

• national prestige.

The DFA argued that the national prestige of South Africa would be buttressed by her becoming reintegrated into the international community. In addition, if South Africa were to sign the NPT, as part of Article IV of the treaty, it would have access to nuclear technology for peaceful use, which South Africa needed for its domestic energy needs.574

In 1987, President PW Botha announced that his government was ready to sign the NPT in the near future and open up its facilities for IAEA inspection.575 Subsequently, international pressure grew on South Africa to accede to the NPT.576 In 1988, Pik Botha admitted that South Africa had the capability of producing nuclear weapons, but he did not admit to South Africa having any at that time. 577

Qualitatively, in the discourse presented in the documents cited above, during this period, there was greater alignment in terms of the authority foundation between the apartheid regime and the reversal advocates, especially regarding the authority of the international community.

From the analysis above, it would appear that in the beginning of the acquire stage, the South African state was motivated by rhetorical action in terms of joining the NPT, but towards the end of this stage, it was also motivated by more normative concerns, such as being part of the international community.

Being part of the international community carried with it certain material and strategic benefits in terms of access to nuclear technology for the energy needs of South Africa. However, it is also evident that a greater moral alignment at this time, at least on the authority foundation, coincides with the South African decision to accede to the NPT and give up its weapons.

While the above does not prove that it was specifically moral claims that made South Africa engage in disarmament, it does demonstrate that an alignment in moral foundations in claims made by the state and reversal advocates when normative concerns were being articulated by the state corresponded to policy responsiveness. It is also to be noted that when moral alignment was not occurring, the ANC and the AAM were engaging in accountability politics through the IAEA, UNGA, and other international state and nonstate actors in order to isolate South Africa culturally, politically, and diplomatically.

Contribution of the study

In identifying the conditions under which moral claims contribute to reversal, this study addressed the gap in the literature on nuclear reversal. Secondly, by applying MFT in a case where a mere quantitative analysis of the text was not feasible, it also shows that a quantitative analysis by itself does not necessarily help prove moral alignment. Instead, a qualitative analysis provides a clearer sense of whether alignment is occurring or not. The study, hence, made a methodological contribution as well by advancing the literature on MFT. This research was also relevant to policy, since if moral claims were found to be effective under certain conditions, this can have direct relevance for non-proliferation and disarmament strategies pursued by states and NSAs.

439 Several peace activists coming from faith traditions have written about the destructive power of the atom bomb and made moral claims on why nations should not possess them. See, for example, works by Dorothy Day, Reinhold Niebuhr, Thomas Merton and Henry Nouwen.

440 Stephen D. Krasner (1983) defines regimes as "principles, norms, rules, and decision-making procedures around which actor expectations converge in a given issue-area." (1). Please see Krasner, Stephen D., ed. International regimes. Cornell University Press, 1983. See K Moore. Disrupting science: Social movements, American scientists, and the politics of the military, 1945-1975. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009 and A Valiunas. "The agony of atomic genius". The New Atlantis: A Journal of Technology and Society 14. 2006. 85-104 for more on the moral claims made by some of the scientists from the Manhattan Project on the destructive power of the atom and H-bomb.

441 Levite (2003) defines nuclear reversal as "the phenomenon [in] which states embark on a path leading to nuclear weapons acquisition, but subsequently reverse course, though not necessarily abandoning altogether their nuclear ambitions". See AE Levite. "Never say never again: Nuclear reversal revisited". International Security 27/3. 2002. 3. For this paper, I use the term 'nuclear reversal' only in the context of a nuclear weapons programme and not pursuit of civil applications of nuclear energy.

442 See JM Gustafson. The church as moral decision-maker. Philadelphia: Pilgrim Press, 1970, 90.

443 The World Campaign Against Military and Nuclear Collaboration with South Africa (to be referred to as the 'World Campaign' in the rest of the paper) was launched in 1979 in Oslo, Norway, at the initiative of the AAM and had the patronage of several heads of state and the United Nations. They worked with AAM to strengthen an arms embargo against South Africa and served as a source to the United Nations Security Council for information on violation of the embargo. See <https://africanactivist.msu.edu/organizationphp?name=World+Campaign+Against+Military+and+Nuclear+Collaboration+with+South+Africa>.

444 SD Sagan. Why do states build nuclear weapons?: Three models in search of a bomb. International security. 21(3). (1996):54-86.

445 See RJ Einhorn, KM Campbell & M Reiss. The nuclear tipping point: Why states reconsider their nuclear choices. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2004; Levite op. cit.; M Reiss. Bridled ambition: Why countries constrain their nuclear capabilities. Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 1995; and AH Montgomery. "Stop helping me: When nuclear assistance impedes nuclear programs". In AM Stulberg & M Fuhrmann, eds., The nuclear renaissance and international security. Stanford, CA: Stanford Security Studies, 2013, 177-202.

446 See TV Paul. Power versus prudence: Why nations forgo nuclear weapons (Vol. 2). Quebec City, Canada : McGill-Queen"s University Press, 2000; NP Monteiro & A Debs. "The strategic logic of nuclear proliferation". International Security 39/2. 2014. 7-51; and G Gerzhoy. "Alliance coercion and nuclear restraint: How the United States thwarted West Germany"s nuclear ambitions". International Security Apr 1;39(4), 2015. 91129.

447 See AJ Coe & J Vaynman, Collusion and the nuclear nonproliferation regime. The Journal of Politics. Oct 1;77(4). 2015. 983-97; SE Kreps & M Fuhrmann. "Attacking the atom: Does bombing nuclear facilities affect proliferation?" Journal of Strategic Studies 34/2. 2011. 161-187; and E Mattiacci & BT Jones. "(Nuclear) change of plans: What explains nuclear reversals?" International Interactions 42/3. 2016. 530558.

448 Scholars define 'nuclear hedging' as a strategy of maintaining non-proliferant status by avoiding actively seeking to acquire weapons, but at the same time insuring against future security threats by retaining the ability to assemble nuclear weapons within a short period. See Mattiacci & Jones op. cit. and M Fuhrmann & B Tkach. "Almost nuclear: Introducing the nuclear latency dataset". Conflict Management and Peace Science 32/4. 2015. 443-461.

449 JE Hymans. Achieving nuclear ambitions: Scientists, politicians, and proliferation. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012; Montgomery op. cit.; Mattiacci & Jones op. cit.

450 See Hymans op. cit. and Montgomery op. cit.

451 E Solingen. "The political economy of nuclear restraint". International Security 19/2. 1994. 126-169. [ Links ]

452 MR Rublee. Nonproliferation norms: Why states choose nuclear restraint. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 2009; MR Rublee. "Taking stock of the nuclear nonproliferation regime: Using social psychology to understand regime effectiveness". International Studies Review 10/3. 2008. 420-450.

453 Rublee, "Taking stock ..." op. cit.

454 This is not to say that security considerations did not play a role; rather that normative considerations were also a contributing factor.

455 W Stumpf. "South Africa"s nuclear weapons program: From deterrence to dismantlement". Arms Control Today 25/10. 1995. 3. Stumpf (1995) attributes South Africa's decision to dismantle its weapons programme to a change in its external security conditions driven by the following developments: (i) ceasefire with Namibia, formerly West South Africa, and its subsequent independence on 1 April 1989; (ii) phased withdrawal of Cuban forces in 1988 from Angola following a tripartite agreement between South Africa, Angola and Cuba; and (iii) the fall of the Berlin Wall in December 1989 and an impending end to superpower rivalry in Africa. See also JW de Villiers, R Jardine & M Reiss. "Why South Africa gave up the bomb". Foreign Affairs 72. 1992. 98-109 and D Albright & M Hibbs. "South Africa: The ANC and the atom bomb". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 49/3. 1993. 32-37.

456 See WJ Long & SR Grillot. "Ideas, beliefs, and nuclear policies: The cases of South Africa and Ukraine". The Nonproliferation Review 7/1. 2000. 24-40; VJ Intondi. "Nelson Mandela and the bomb". HuffPost. 9 December 2013. <https://www.huffingtonpost.com/vincent-intondi/nelson-mandela-and-the-bo_b_4407788.html> Accessed on 8 January 2020 ; and Wilson Center. "Memorandum, "Main points arising from luncheon on 14 November 1989'". 17 November 1989. History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive. <https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/123059> Accessed on 2 March 2020.

457 President De Klerk is the former president of the apartheid government in South Africa who dismantled the South African nuclear weapons programme. For the full interview, see U Friedman. "Why one president gave up his country"s nukes". The Atlantic. 9 September 2017. <https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2017/09/north-korea-south-africa/539265/> Accessed on 2 April 2022.

458 See, for example, a poster produced by the World Campaign Against Military and Nuclear Collaboration with South Africa, available at <http://africanactivist.msu.edu/image.php?objectid=32-131-2B7>.

459 These activists echoed Langston Hughes's assertion that "racism was at the heart of Truman's decision to use nuclear weapons in Japan" - a conviction that got stronger as the USA considered using nuclear weapons in the Korean and Vietnam war. See V Intondi & VJ Intondi. African Americans against the bomb: Nuclear weapons, colonialism, and the Black Freedom Movement. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2015, 3 and H Gusterson. "Nuclear weapons and the other in the Western imagination". Cultural Anthropology 14/1. 1999. 111-143.

460 DC Atwood. "NGOs and disarmament: Views from the coal face". Disarmament Forum 1. 2002. 5-14. The Nuclear Freeze campaign, a civil society effort, helped ensure that arms control was on the agenda of states. See also DS Meyer. A winter of discontent: The nuclear freeze and American politics. New York: ABC-CLIO, 1990.

461 JW Busby. Moral movements and foreign policy (Vol. 116). New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010; K Quissell. "The impact of stigma and policy target group characteristics on policy aggressiveness for HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis". PhD dissertation. American University, 2017.

462 ME Keck & K Sikkink. Transnational Advocacy Networks in International Politics: Introduction. In Activists beyond borders: Advocacy networks in international politics Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. 2014; A Acharya. "How ideas spread: Whose norms matter? Norm localization and institutional change in Asian regionalism". International Organization 58/2. 2004. 239-275.

463 Whereas moral claims are value-based statements with claims to universal validity, moral discourse is "an activity that involves the critical discussion of personal and social responsibilities in the light of moral convictions about which there is some consensus and to which there is some loyalty". See JM Gustafson. Op. cit.

464 Deitelhoff and Muller (2005) argue that whereas contested norms and weak institutions favour rhetorical action, in the presence of strong institutions and contested norms, communicative action prevails. Similarly, when norms are stable and institutions are strong, norm-regulated behaviour occurs. See N Deitelhoff & H Muller. "Theoretical paradise - empirically lost? Arguing with Habermas". Review of International Studies 31/1. 2005. 167-179.

465 J Haidt, J Graham & C Joseph. "Above and below left-right: Ideological narratives and moral foundations". Psychological Inquiry 20/2-3. 2009. 110-119; J Graham, J Haidt, S Koleva, M Motyl, R Iyer, SP Wojcik & PH Ditto. . J Graham, J Haidt, S Koleva, M Motyl, R Iyer, SP Wojcik, PH Ditto. Moral foundations theory: The pragmatic validity of moral pluralism. In Advances in experimental social psychology. 47. 2013. 55-130.. For an in-depth view into MFT, see <http://moralfoundations.org/>. Publications using MFT are listed at <http://moralfoundations.org/publications>.

466 BC Rathbun, R. Stein. Greater goods: morality and attitudes toward the use of nuclear weapons. Journal of conflict resolution. 64(5). (2020). 787-816. M Feinberg & R Willer. "From gulf to bridge: When do moral arguments facilitate political influence?" Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 41/12. 2015. 1665-1681; J Haidt & MA Hersh. "Sexual morality: The cultures and emotions of conservatives and liberals". Journal of Applied Social Psychology 31/1. 2001. 191-221; S Clifford & J Jerit. "How words do the work of politics: Moral foundations theory and the debate over stem cell research". The Journal of Politics 75/3. 2013. 659-671.

467 Busby op. cit.; Quissell op. cit.

468 Keck & Sikkink (95) op. cit. A Klotz. "Transnational activism and global transformations: The anti-apartheid and abolitionist experiences". European Journal of International Relations 8/1. 2002. 49-76; W van Deburg. "William Lloyd Garrison and the 'pro-slavery priesthood': The changing beliefs of an Evangelical Reformer, 1830-1840". Journal of the American Academy of Religion 43/2. 1975. 224-237.

469 See Acharya op. cit.

470 See Acharya op. cit. and C Ulbert, T Risse & H Miiller. Arguing and bargaining in multilateral negotiations. Final report to the Volkswagen Foundation, 2004, 3. available at https://www.polsoz.fu-berlin.de/polwiss/forschung/international/atasp/Publikationen/4_artikel_papiere/26/ulbert_risse_mueller_2004.pdf. Accessed on 28 May 2022.

471 Political actors have employed transnational moral authority as a power resource in order to influence transnational outcomes since pre-feudal times in Europe. See RB Hall. "Moral authority as a power resource". International Organization 51/4. 1997. 591-622; DA Lake. "Rightful rules: Authority, order, and the foundations of global governance". International Studies Quarterly 54/3. 2010. 587-613; RL Brown. Nuclear authority: The IAEA and the absolute weapon. Washington, DC : Georgetown University Press, 2015; and A Grzymala-Busse. Nations under God: How churches use moral authority to influence policy. Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2015.

472 See Keck and & Sikkink op. cit. (2004) (95)

473 See RB Hall & TJ Biersteker, eds. The emergence of private authority in global governance (Vol. 85). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

474 For example, personalities such as the Dalai Lama, Desmond Tutu, the Pope and Thomas Merton, among others.

475 See J Farrell & M Rabin. "Cheap talk". The Journal of Economic Perspectives 10/3. 1996. 103-118.

476 The term "rhetorical entrapment" arises from the idea of "argumentative self-entrapment" proposed by Risse and Sikkink (1999). T Risse & K Sikkink, Human, rights norms into domestic practices: introduction. The Power of Human Rights: International Norms and Domestic Change. 1999 Aug 5;66:1; 254. Also see RR Krebs & PT Jackson. "Twisting tongues and twisting arms: The power of political rhetoric". European Journal of International Relations 13/1. 2007. 35-66.

477 See Keck & Sikkink op. cit. (95)

478 Quissell op. cit. found that a misalignment in moral foundations in claims made by policy gatekeepers and civil society advocates for policy responses to TB and HIV/AIDS in South Africa potentially contributed to a delay in the adoption of universal treatment. She argues that when moral alignment eventually occurred, it was through leverage politics and regime change. See also Keck & Sikkink op. cit.

479 S Singh & CR Way. "The correlates of nuclear proliferation: A quantitative test". Journal of Conflict Resolution 48/6. 2004. 859-885, (866) [ Links ]

480 AE Levite. Never say never again: nuclear reversal revisited. International Security. Dec 1;27(3). (2002):59-88.

481 Singh &Way. Op. cit.

482 I do so because several states, such as Japan, South Korea, Brazil and Taiwan, which had nuclear weapon programmes at some point, gave up plans to actively acquire nuclear weapons, but possess nuclear latency. See Fuhrmann & Tkach op. cit.

483 I draw from Jacob (2013) and Matiacci and Jones (2016), who build up on Singh and Way (2004) in conceiving of nuclear reversal as a state transitioning from stages 1, 2 or 3 to a stage lower than their current stage of nuclearness. See N Jacob. "Understanding nuclear restraint: What role do sanctions play? A study of Iraq, Taiwan, Libya, and Iran, 2013. (Unpublished doctoral thesis), American University; E Mattiacci & TJ Benjamin. (Nuclear) change of plans: What explains nuclear reversals? International Interactions 42/3. 2016). 530-558. and Singh &Way. Op. cit.

484 Moral Foundations Dictionary. 2012. <http://moralfoundations.org/sites/default/files/files/downloads/moral%20foundations%20dictionary.dic> Accessed on 8 January 2020.

485 See National Nuclear Regulator. "History" 2022. <https://nnr.co.za/about-us/history/> Accessed on 31 March 2022. HEU generally refers to uranium that has been enriched to a level that contains 20% of the U-235 isotope - this can be used to create a gun-type nuclear device. Uranium that is considered to be weapons-grade usually contains 90% of the U-235 isotope. See AJA Roux & WL Grant. "The South African uranium enrichment project". Presentation to the European Nuclear Conference. April 1975. <https://inis.iaea.org/collection/NCLCollectionStore/_Public/06/196/6196511.pdf?r=1> Accessed on 31 March 2022.

486 Wilson Center. "South African Department of Foreign Affairs, Announcement by South African Prime Minister Vorster". 20 July 1970, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive. <https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/114143> Accessed on 31 March 2022.

487 See V Harris, S Hatang & P Liberman. "Unveiling South Africa"s nuclear past". Journal of Southern African Studies 30/3. 2004. 457-476.

488 See A von Baeckmann, G Dillon & D Perricos. "Nuclear verification in South Africa". International Atomic Energy Agency Bulletin (Austria) 37. 1995. 42-48.

489 Ibid.

490 Ibid.

491 J-A van Wyk. "Atoms, apartheid, and the agency: South Africa"s relations with the IAEA, 1957 -1995". Cold War History 15/3. 2015. 395-416. doi: 10.1080/14682745.2014.897697

492 A-M van Wyk. "South African nuclear development in the 1970s: A non-proliferation conundrum?" The International History Review 40/5. 2018. 1157-1158. doi: 10.1080/07075332.2018.1428212

493 RE Horton. Out of (South) Africa: Pretoria's nuclear weapons experience. Occasional paper no. 27. USAF Institute for National Security Studies. 1999. <https://nuke.fas.org/guide/rsa/nuke/ocp27.htm> Accessed on 31 March 2022.

494 Von Baeckmann et al. op. cit.; Van Wyk op. cit. (47)

495 IAEA puts the date at 1944 of the then South African prime minister Vorster approving a limited programme for developing a nuclear deterrent. See Von Baeckmann et al. op. cit. and Van Wyk op. cit. Other sources have dated the approval for such a programme to 1977/1978. See W Stumpf. "Birth and death of the South African Nuclear Weapons Programme". Paper presented at the 50 Years After Hiroshima Conference, Castiglioncello, 28 September - 2 October 1995. <http://www.fas.org/nuke/guide/rsa/nuke/stumpf.htm> Accessed on 31 March 2022 and P Liberman. "The rise and fall of the South African bomb". International Security 26/2. 2001. 45-86.

496 See H Steyn, R van der Walt & J van Loggerenberg. Armament and disarmament: South Africa's nuclear weapons experience. Lincoln, Nebraska: iUniverse Books, 2003 and J Schofield. Strategic nuclear sharing. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014, 86-92.

497 Von Baeckmann et al. op. cit.

498 Ibid. See also JW de Villiers, R Jardine & M Reiss. "Why South Africa gave up the bomb". op. cit.

499 Wilson Center. "Speech by South African president FW de Klerk to a joint session of Parliament on Accession to the Non-Proliferation Treaty". 24 March 1993. History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive. <https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/116789> Accessed on 31 March 2022 . See also Stumpf, "Birth and death ..." op. cit.

500 I choose 1970 as the beginning of the Explore stage since in 1970, South Africa announced the construction of the Y-plant at Valindaba for the production of enriched uranium, ostensibly for peaceful use. 1978 is chosen as the year that the Explore stage was completed and the Acquire stage began, as in 1978, the first HEU product was developed and withdrawn from the Valindaba plant. See Von Baeckmann et al. op. cit.

501 Stumpf, "South Africa"s nuclear weapons program ..." op. cit.

502 United Nations Security Council. "Resolution 418". 4 November 1977. <https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/66633?ln=en> Accessed on 30 March 2022; United Nations General Assembly. "Resolution 1761 (XVII). The policies of apartheid of the Government of the Republic of South Africa". 1962. <http://www.worldlii.org/int/other/UNGA/1962/21.pdf> Accessed on 30 March 2022.

503 United Nations General Assembly. "Resolution 35/206. Policies of apartheid of the Government of South Africa". 1980. <https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/614062> Accessed on 30 March 2022.

504 See <http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/3324(XXIX)>.

505 United Nations General Assembly. "Resolution 3411 (XXX). Policies of apartheid of the Government of South Africa". 1975. <https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/190013?ln=en> Accessed on 30 March 2022,

506 Documents of resolutions adopted at UNGA in 1976, 1977 and 1978 available at <https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/RESOLUTION/GEN/NR0/301/89/IMG/NR030189.pdf?OpenElement>, <https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/RESOLUTION/GEN/NR0/313/40/IMG/NR031340.pdf?OpenElement> and <https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/RESOLUTION/GEN/NR0/362/01/IMG/NR036201.pdf?OpenElement>.

507 These reports can be accessed at https://www.iaea.org/gc-archives.

508 Annual reports issued between 1959 and 1975 available at IAEA's General Conference Archives: <https://www.iaea.org/gc-archives>.

509 IAEA. "Annual report (1 July 1973 - 30 June 1974)". GC(XVIII)/525. <https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/gc/gc18-525_en.pdf> Accessed on 30 March 2002.

510 IAEA. "Annual report (1 July 1975 - 30 June 1976)". GC(XXI)/580. <https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/gc/gc21-580_en.pdf> Accessed on 30 March 2002.

511 Ibid., p. 6.

512 IAEA. "Annual report for 1977". GC(XXII)/597. <https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/gc/gc22-597_en.pdf> Accessed on 30 March 2002.

513 Ibid., p. 8.

514 IAEA. "Annual report for 1978". GC(XXIII)/610. <https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/gc/gc23-610_en.pdf> Accessed on 30 March 2002.

515 IAEA. "General Conference: Twenty-third Regular Session: 4-10 December 1979: Record of The Two Hundred and Eleventh Plenary Meeting". GC(XXIII)/OR.211. <https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/gc/gc23or-211_en.pdf> Accessed on 30 March 2002.

516 See <http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/3324(XXIX)>.

517 United Nations General Assembly. "Resolution 3411 (XXX). Policies of apartheid of the Government of South Africa". 1975, 38. <https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/190013?ln=en> Accessed on 30 March 2022.

518 Ibid., p. 39.

519 Sechaba. "The will of an entire people forged under fire". Editorial. 1. First quarter. 1977. 1. <https://www.sahistory.org.za/sites/default/files/archive-files3/SeJan77.pdf> Accessed on 30 March 2022.

520 Ibid., p. 12.