Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Childhood Education

On-line version ISSN 2223-7682

Print version ISSN 2223-7674

SAJCE vol.12 n.1 Johannesburg 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v12i1.1255

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Teaching critical thinking and voice in history essays: A spiderweb tool

Sarah Godsell

Department of Social and Economic Sciences, Faculty of Humanities, Wits School of Education, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: The history essay, and historical writing, are crucial forms of assessment in History throughout primary and high school education. This article draws from an autoethnography of teachings in a pre-service history teachers' school classroom. This article discusses obstacles students experience in conceptualising and writing the history essay. A tool is introduced to overcome these obstacles.

AIM: This article presents a possible intervention in the form of a classroom tool.

SETTING: This classroom tool is presented in a pre-service history teachers classroom (tertiary). It is presented as a method to teach history in classrooms of senior phase (SP), intermediate phase (IP), and further education and training (FET) phase

METHODS: This article uses a qualitative methodology that draws on autoethnography and reflective teaching methodology, allowing me to understand and analyse the processes taking place in my own classroom. This was authorised with an ethics protocol number (H18/10/10

RESULTS: The observations from the case study class showed that the tool provided possibilities for understanding the mediation of knowledge used in an essay, in a way that facilitates critical thinking and voice.

CONCLUSION: This tool provides a possible class intervention that can range from primary to high school. It allows teachers to understand what levels their students' thought need to operate on to teach essay and paragraph writing.

CONTRIBUTION: This spiderweb tool can be used directly in class to demonstrate how the different points of knowledge relate to each other in making an argument. This supports critical thinking and the development of voice.

Keywords: Critical thinking; history education; teacher education; assessment; history methodology; Bloom's taxonomy; classroom tools.

Introduction

Towards developing a tool for critical thinking in teaching history in an emergent democracy

History is widely acknowledged as an important discipline for critical thinking (Bam, Ntsebeza & Zinn 2018; Ndlovu et al. 2018; Wineburg 2018; Zinn 2005). It is also an important, contested political and social tool. In light of this, developing one's own voice in relation to history writing is important for history learners. The following quote from the Ministerial Task Team, investigating whether or not history should be made a compulsory subject in South African high schools, demonstrates this:

The main aims or objectives of History Teaching in the African Continent are to foster understanding of the past and its relevance; to enhance the understanding of, and capacity to apply, historical concepts and methods; to promote critical thinking; and to inspire a sense of (national/African) belonging and identity. Other aims include evoking patriotism; encouraging active and responsible citizenship, values, attitudes and behaviours, as well as fostering skills conducive to learning how to live together. (Ministerial Task Team on History Curriculum; Ndlovu et al. 2018:13)

The above quote suggests that history must teach critical thought but also patriotism and citizenship. The quote is specifically responding to research investigating how history is taught in the African countries investigated by the task team, but citizenship is still in the current South African school history curriculum. The problem that arises from this is the implied and enacted value systems in the curriculum, where a teacher's personality, positionality and ideology play a role. Critical thinking skills allow a meaningful engagement, and the possibility for a meaningful mediation with the issues brought to the fore in the quote. How do we develop this into history pedagogy:

Learners often experience difficulty in writing at length and in essay format. They need to be trained to select the information they want to include (only to choose what is relevant), to arrange the information (to put it in order together with other information) and to connect information (to make a logical sequenced argument). (Department of Basic Education 2011:32)

The critical thinking skills that develop through historical thinking skills, such as multiperspectivity, offer students a way to hold the complexities of past and present (Seixas & Morton 2012). History taught without critical thinking skills can become an unreflective political tool. History students can be overwhelmed with factual historical knowledge in which they can see no purpose or relevance, in which those attributes have been erased (Wineburg 2018). In this article, I offer a classroom tool to provide an option of how critical thinking in history essays or paragraphs can be taught, both conceptually and through a classroom activity.

History has also been widely acknowledged as a crucial liberation tool (Freire 1996; Teeger 2015; Zinn 2005). This requires a complex understanding of history, of historical knowledge and of evidence. For this, history needs to be taught in a way that opens doors for critical thought and a multiplicity of voices - whether we are teaching the history of transport, of apartheid, of ancient Egypt or of the transatlantic slave trade.

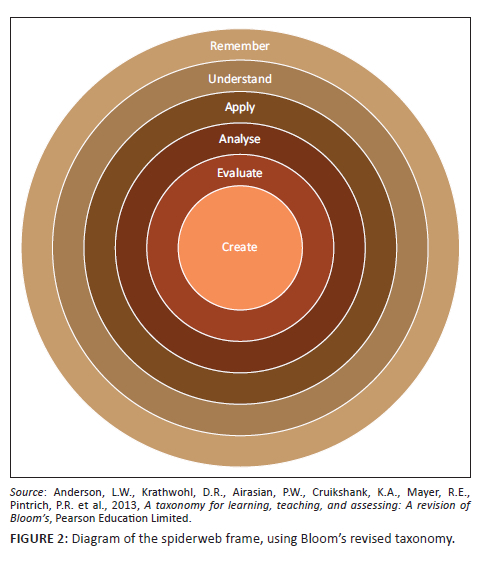

In this article, to expound how the tool I present addresses these issues conceptually, I will explore an interpretation of what voice is in the context of a history essay and how it aligns with, and must be held by, critical thinking. I will also give an example of a practical task which I have developed to break down the history essay into steps which align with Middendorf and Pace's 'decoding the disciplines' (Middendorf & Pace 2004). The practical task is named the 'Essay Spiderweb'. It requires, among other things, students to build a physical representation of their essay in the form of a spiderweb that is set up with the thinking levels of Bloom's taxonomy, using preselected pieces of evidence placed on the spiderweb structure (Anderson et al. 2013). I use Bloom's revised taxonomy to frame critical thinking, as students in a Bachelor of Education programme are familiar with this way of signalling and framing different thinking levels. It also makes the tool helpful in primary or high school classrooms.

History essays: Critical thinking and voice

History is just essays and essays. There is no thinking. Geography is just more hands on, you think more. (Anonymous student, Wits School of Education 2018)

I overheard this statement in my office at the School of Education in 2018. As a historian, but more importantly as a lecturer of preservice history teachers, I find this statement disturbing. History is all about thinking. History essays are meant to demonstrate the student or learner's thinking, and they are a crucial form of history assessment, requiring students to master a set of skills: working with evidence (analysing, sourcing, contextualising, corroborating [Wineburg 2001]), constructing an argument, demonstrating historical thinking skills (Seixas & Morton 2012) and academic writing (McKenna 2010). Voice is also crucially linked to all these skills. Voice is what distinguishes one essay from another and moves an essay from a regurgitated set of facts to an essay using historical thinking skills. Critical thinking ties all these skills together.

Any approach that draws students away from acknowledging themselves in their own essays detracts from an honesty of positionality that I would argue is also crucial to history learners, history students, historians and history teachers alike (Teeger 2015; Wills 2016).1

Students often seem to dichotomise critical thinking and an idea of voice: either everything is thought and felt (voice) or argued and substantiated (critical thinking), where they feel they are allowed to have no words or ideas of their own.2 This has been reinforced by a colonial education system in which 'rational' is valid and 'emotional' is not (Godsell 2019). In attempts to get students to read and engage with the arguments and content of subject experts, students are reminded that these are not their ideas, that they do not have the knowledge, that they must not plagiarise, that they must rewrite in their own words (at the same time as we tell them they do not have the knowledge). There is a truth and relevance to this - first-year students come into the university to learn, relying on the lecturer and the readings provided by us to expose them to both argument and evidence. From this, they produce an essay that is generally not relying on any of their prior knowledge. They need to reference, to acknowledge where the work is coming from. They did not 'know' the information themselves. Argument needs to be based on evidence, which needs to be drawn from, in this case, the readings we give them (Monte-Sano 2012). However, there is also a truth and relevance to the fact that any essay, produced by any individual, is filtered through that individual and their individual choices, conscious and subconscious, around content, fact and phrasing.

What is it about history essays that makes students feel these assignments are about historical knowledge ('facts') and not about thinking? Another encounter I had with a student further informed my insight. In a conversation about plagiarism, on being asked to use their own words, the student exploded: 'I have no words'.3

How is historical fact and historical information portrayed in history classrooms, at primary, secondary and tertiary level? In the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) curriculum, the primary school facts can be portrayed as more 'fairy tales' (e.g. using the phrasing such as 'long ago' rather than a historical timeframe). This adds to a sense of mysticism and detracts from a sense of real history, important to inculcate in younger students. Where do we lose students in historical evidence, 'facts' and arguments they feel must not be filtered through their own thinking? And how do we shift this?

In an era of increasing student numbers and unmanageable workloads on lecturers (Biggs 2014), lecturers are pushed to use assessments that are less time-intensive to mark. We struggle to find such assessments that, according to key assessment principles, are valid, reliable, relevant and develop transferable skills (Rust 2001). The comments of the two students above highlighted a deficiency in the essay as assessment in history teaching. If a history essay is not teaching critical thinking, it is not valid, reliable, relevant or teaching transferable skills. Many history teachers have experienced essays as lists of standalone pieces of historical information, with little or no argument or voice (Monte-Sano 2012; Tambyah 2017).

The tool I designed involved breaking down the process of writing an essay into steps organised around building an argument spiderweb, with pre-preparation and post-reflection. It involves reading, choosing evidence, group work, peer review, individual writing and physically engaging with the different levels of critical thinking involved in transforming evidence into an essay. Suggesting this breakdown can help in shifting students from rote learning to critical engagement with history as narrative, as construct, as argument and as an essential component for history teaching in an emergent democracy.4

Theoretical framework

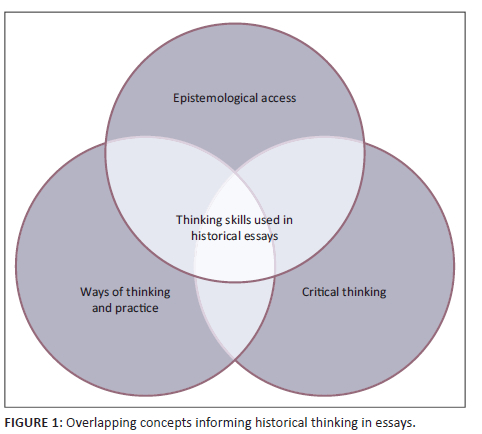

My epistemological framework evolved from a set of interlinking concerns around critical thinking, historical thinking skills, students' relationship with knowledge, voice and construction of argument and how to help students write all of these down. While this sounds very messy, the key elements distilled can be framed through: critical thinking, ways of thinking and practice (WTP) (as a lens for learner-oriented assessment [Carless 2014]) and epistemological access (Morrow 2009).

Critical thinking involves analysing evidence, creating an argument (voice) and relational knowledge composition. The analysis of evidence is a key historical thinking skill and one essential for creating historical argument (Wineburg 2001).

Epistemological access (Morrow 2009) encompasses critical thinking and WTP, with a particular focus on how the students are able to access the knowledge they are exposed to in a university context. There is a specific focus on semiotics, on what is unsaid, or said less explicitly, that leaves students lost. Carless (2014) uses WTP as a lens to view learning-oriented assessment (LOA), where the learners are inculcated into the ways of history as a discipline. In my context, this incorporates how to make a historical argument and historical thinking skills.

The WTP of the university are also a code students must crack to be able to produce academic writing. My focus is on how students are able to access and position themselves in relation to the historical articles, information and narrative they encounter in our courses. Underpinning all of these are the questions: 'how do we use history essays to teach students historical and critical thinking?'5 and 'how can students access, value and deploy critical thinking skills in historical essays?'

Supporting critical thinking with assessment theory

I use several aspects of assessment theory to support the task design. Learner-oriented assessment (Carless 2014) stresses three aspects that create assessments structured around learners: the assessment itself, the students' development of self-evaluative practices and students' engagement with feedback. I have built these into the various steps of the spiderweb assessment, as will be unpacked in detail below.

Biggs' (2014) concept of constructive alignment (CA) advocates an inclusive system of interrelated assessments, learning outcomes and teaching and learning experiences. He focuses on the clarity of intended learning outcomes (ILO) and argues that teaching methods and assessment practices must work together and must focus on what the students actually learn, rather than what the teacher teaches. This requires careful work in course design and in the mediation of assessments and marking criteria. A learner-oriented focus is crucial for my chosen pedagogy, but Biggs' focus on learning by doing, learning with the objective of being able to apply functioning knowledge, is especially pertinent in a teaching methodology course. This is why this tool is designed for both university and basic education classrooms. This also, as Biggs and Tang suggest, bridges the gap between declarative and functioning knowledge (Biggs & Tang 2014).

I draw from Biggs' CA crafting towards an alignment between all aspects of teaching, each section of the assessment tool and ILOs, with a view that each part of the assessment assists students in constructing functional knowledge (through navigating declarative knowledge). This is in line with the skills intended to be taught through history in the CAPS document (although these skills are not present in the actual lessons outlined in CAPS [CAPS 2011]).

The constraints of CA, as partly discussed by Biggs, emanate from the increasingly corporatised and time-pressured higher education system. While it is possible for me to use this tool in a course of 49 pupils, it is much harder to imagine using CA effectively in a class of 400.6 This points to the importance of constantly developing new teaching tools to match the class but also to the importance of constant mediation in the teaching tools and assessments of a course.

I use two different types of taxonomy in the spiderweb assessment: Bloom's revised (Anderson & Krathwohl 2001) and structure of observed learning outcomes (SOLO) taxonomies (Biggs & Collis 1982). The spiderweb assessment is a way to embed Bloom's taxonomy inside the exercise and link this to SOLO taxonomy through the marking criteria. The rubric that I used to mark the assessment is a rubric using SOLO taxonomy. Rubrics are a way to mediate the assessment process and the marking criteria (Dison & Rembach 2016), particularly the SOLO taxonomy rubric. They argue that rubrics have the potential to scaffold students in the academic metalanguage of a discipline and specific learning outcomes. They also argue that rubrics can assist in aligning assessments, learning outcomes and teaching and learning exercises, leading to effective CA, especially when used in formative learning that engages students in the learning concepts, with 'students becoming effective learners' (Rembach & Dison 2016:70).

The SOLO taxonomy states that learners' answers improve in two ways: in amount of information given (quantitative) and in quality of learning (qualitative - in the taxonomy relational). The task-specific rubric designed along these lines provides learners with specific criteria with which they can measure the improvement, or the extent, of their learning and ability to answer or engage with the questions in the assignment (Rembach & Dison 2016).

Rembach and Dison argue for rubrics to be introduced into the teaching and learning experiences so that students can engage with, and challenge, the assessment criteria on which they will be marked. This can be used to enhance students' confidence and also change the function of rubrics from marking aides to teaching and learning tools (Rembach & Dison 2016). This means that rubrics are used as assessments for learning to give epistemological access to the procedural knowledge and shift from surface to deep learning. This approach ties into (and requires) a mediated and continuous feedback process.7

Shalem et al. (2013) used Morrow's (2009) concept of epistemological access to describe what is required for students to perform well in university, combining and understanding 'what is accepted in academic writing and what is expected in University' (Shalem et al. 2013:1082). Shalem et al. (2013) argue that writing, in the context of the university, takes on a specific epistemic form that alienates students (especially average to low-achieving students), as it looks different from what they encountered in a school context. They show that students experience difficulty in positioning themselves with regard to knowledge authorities (their own position in relation to making sense of the text). However, if students are to understand that historical knowledge is constructed like any other knowledge form and how to navigate themselves through primary and secondary sources, through multiple historical narratives and perspectives, they need to understand the epistemic form of historical (university-level) writing. This is so they get a clear grasp on the historical thinking skills involved in writing historical narrative and knowledge. They need to understand their own relationship to the historical knowledge they are interacting with, whether in the form of primary or secondary sources. To achieve this in the tool, I split the assignment into steps that limit the amount of information the students interact with and focus rather on the choices that students make with what information to use and how to use that information.

Feedback is a crucial part of learning-oriented assessments (Carless 2015). However, students often struggle to fully understand feedback received from lecturers (Shalem et al. 2013). Without effective feedback on why and how critical thinking is incorporated into an essay, the history essay will remain a rote learning tool. I have incorporated feedback into my tool design in different ways: feedback on the rubric (group in class), choosing evidence in a group (group discussion) peer review of the essay and written feedback on the final assignment. As some elements of the assessment were also completed in the class, students had the opportunity to discuss among themselves as I monitored and gave input, either to direct questions or to the discussions the students were having.

Carless (2014) devised a pyramid of what is needed to develop learning-oriented assessment, the two building blocks being 'developing evaluative practice' and 'student engagement with feedback'. I used these ideas in constructing an assessment that allows feedback at multiple levels, from peers and in groups where debates ensued in the class. This brought students to different ideas about history essays, how they should be written and thought.

Ways of thinking and practice are used here as part of a constructivist approach. The lecturer is inducting the students into WTP for a particular discipline and also facilitating their own knowledge process into constructing their WTP. A colleague, Anna Kharuchas, phrased it beautifully when they said 'we need to give the students the tools and the toys with which to write' (and think).

Historical thinking and critical thinking: Locating in the discipline of history

In this section, I discuss ideas of 'what makes a good history essay' (Monte-Sano 2012) to show how crucial critical thinking is and how the tool developed contributes to this cruciality.

In the History Methods courses I teach (where we explore pedagogical methodologies used to teach history in school), we use two key theorists: Peter Seixas and Sam Wineburg. We work with what are known as the big six historical thinking concepts (Seixas & Morton 2012) and historical thinking (Wineburg 2001). Both Wineburg and Seixas write of processes of procedural or functioning knowledge (knowledge of concept, process and skill), but they approach the idea in different ways. Wineburg (2001) writes about historical thinking and historical understanding, and Seixas (2004) writes about historical consciousness. Their common ground is that critical thinking, higher thinking levels and analysis of sources are a necessity in well-taught history. While this is often set up as a dichotomy between 'knowing history' (declarative or content knowledge) and 'doing history' (procedural knowledge), Ramoroka and Engelbrecht (2015) argue that 'doing history' involves 'knowing history'. This means a knowledge of historical narratives, preferably through different historical perspectives and types of evidence, is necessary for students to approach these histories critically. The interaction of these two types of knowledge (declarative, knowledge 'about' and functioning knowledge that informs action) (Biggs & Collis 1982) has also been widely written about, generally calling for an interaction between the two. This is no different in history. Bloom's taxonomy, Biggs and Tang argue, can be taught as a threshold concept (a concept that leads to a change in student's thinking) to engage both types of knowledge (Biggs & Tang 2011). The idea of using Bloom's taxonomy (as well as SOLO taxonomy) as threshold concepts is fundamental for thinking through the creation of assessment tasks.

In my assessment tool, I need to ensure an engagement with the historical 'facts' or historical evidence that the students need to engage with critical thinking. The primary problem of teaching history as declarative, 'this is the way it was', and as 'one true story' is not a new one, particularly in schools. History is socially and politically loaded. Therefore, I need to acknowledge that part of what is required to get students to engage critically is a 'habit of mind' change (Mezirow 2009), where students have been socialised to understand history as a morass of facts which they have to learn. Thus, thinking about how to teach critical thinking in historical essays, I need to carefully scaffold both declarative and procedural knowledge, so that the historical narratives, or historical evidence, can be critically engaged with through the different levels of thinking (Bloom's revised taxonomy, Anderson & Krathwohl 2001), moving from multistructural to relational knowledge (Biggs & Collis 1982).

Seixas and Morton's (2012) 'big six historical thinking concepts' are ethical thinking, cause and consequence, working with evidence, continuity and change, historical perspectives and historical significance. Yet students who have been taught these concepts still struggle in essays to find their own voice and their own argument and to position themselves in relation to knowledge authorities (Shalem et al. 2013). My designed tool uses Bloom's taxonomy as a threshold concept to bridge the gap between declarative and functioning knowledge.

Epistemic access and voice in essays

As teachers, most of us say we want our students to develop some authority of voice, yet many of our practices have the effect of making students more timid and hesitant in their writing. (Elbow 2000:205)

Continuing the tradition of privileging western epistemic frameworks through reading scholars which do not speak to the Indigenous/Black scholar, I maintain that the contemporary academe annihilates Indigeneity/Blackness through epistemic impositions. (Kumalo 2018:3)

What do lecturers mean when we say 'we want to hear your voice'? The presumption that we hold is that 'we want to know what you think, and why'. Kumalo complexifies this, adding the context of a historically white university (HWU) and the epistemic violence this enacts on anyone falling into context of the Other (Kumalo 2018). This adds additional strands to the idea of voice: whose voice? Making what argument? History can project this epistemic violence by minimising the possibility of voice in essays or necessitating one 'correct' voice as empirically sound. This is not to say that the voice cannot be wrong. In history essays, there can be historical inaccuracies, incorrect facts, factors that were not considered. However, the incontrovertible fact is that the essay is produced through a process of the student's thought:

If we value the sound of resonance - the sound of more of a person behind the words - and if we get pleasure [or derive value] from a sense of the writer's presence in a text, we are often going to be drawn to what is ambivalent and complex and ironic, not just to earnest attempts to stay true to sincere, conscious feelings. (Elbow 2000:207)

This honours the complexity of history, its perception, construction and narrative form. There is another argument to be made, beyond the scope of this article, about the idea that rationality guides emotions (tending to Elbow's argument of not choosing between voice and text but using both lenses). For this article, it is important for students to understand why they make an argument, how their voice constructs, and is constructed, in the essay through critical thinking linked to evidence.

When we ask to hear a student's voice, we are not simply asking to hear a subjective surface view on the subject. Historians, like mathematicians, want to see the workings behind the argument, the working of the sum: why choose this piece of evidence - why support like this - why these dates or statistics - overall, why this argument? This requires different levels of thinking (if we are working with Bloom's taxonomy) and critical creation of argument, as well as critical engagement with evidence.

I argue that an assessment tool which entails the unpacking of the history essay is helpful in scaffolding the students to engage with both argument and voice, using historical thinking skills as well as (and overlapping with) critical thinking skills.

Developing a tool for critical thinking and voice in teaching how to write a history essay

The data for this article were gathered by observing and noting the occurrences in a class where I implemented this tool. The autoethnographic nature of the article is supported by this methodology. When I discuss observations, I am drawing on my own observations from the class and my subsequent thematic analysis of them. Exploring how the materials could be developed towards an assessment tool, I devised an assignment pitched at a high school-level history essay (although this could be adapted for a primary school class too), with specific steps to achieve different kinds of working with evidence, critical thinking and various kinds of feedback.

I locate this assessment tool within both the disciplines of History and of Teacher Education. I use two core texts to do this. Chauncey Monte-Sano (2012), in What Makes a Good History Essay? Assessing Historical Aspects of Argumentative Writing, addresses how students deal with evidence and argues for five characteristics students need to have to construct a convincing historical argument. In Teaching for 'Historical Understanding': What Knowledge do Teachers Need to Teach History?, Tambyah (2017) argues for 'historical consciousness' to be taught through actively prioritising historical concepts and historical inquiry over the content which students seem to get so mired in. These two approaches align with a broader discussion of 'doing history' versus 'knowing history' (Wineburg 2001) that also moves towards the 'what do experts do' approach of Middendorf and Pace (as discussed below).

My intervention in this article is to propose that the tool I created addresses this approach to history, both conceptually and through praxis, drawing on assessment principles and principles of historical and critical thinking.

The steps I built into the assessment (also each marked and weighted) ranged between individual and group work, at home and in class. One step was the physical building of a spiderweb, with evidence on a circle web structure that I had laid out using string on the classroom floor.

I lay out these circles in with string on the classroom floor. Students construct their own web by placing their pieces of evidence within a specifically chosen circle, and then linking with other pieces of their evidence, and the different levels of thinking.

This physical activity is conceptually drawing on Bloom's taxonomy, which the students have been repeatedly exposed to in their Bachelor of Education degree. They are abstractly familiar with this taxonomy of different levels of thinking. The praxis of needing to physically place their different pieces of evidence into different levels of thinking, through which they will construct their argument (and link these different levels too, as it becomes apparent to them that the higher-order thinking skills do not exist in isolation), helps to shift the idea of what critical thinking needs to be in a history essay.

Middendorf and Pace (2004) identified seven steps to overcome obstacles to learning. These steps first relate to what students struggle with, and second relate to how experts practice. I used the concepts discussed above in conjunction with Middendorf and Pace's steps to frame my approach to this deconstructed assessment. This aligns with Biggs' CA model - bringing outcomes-based learning into assessment through consistent verb use, looking at the 'learning through doing' of constructivism (Biggs 2014). This strategy also focuses on 'doing history' rather than 'knowing history' - and this aligns with the idea of teaching critical thinking in history essays.

The essay spiderweb: An outline of a deconstructed history essay, to foreground students' thinking and practice around critical thinking and voice

The assignment is in five steps, each to be completed and marked as part of the overall assessment. It is structured around answering a history essay question, one relating to a section from the Grade 10 history curriculum - the French Revolution. While students tend towards wanting to answer the question in the more conventional way (reading the evidence and writing their essay), this assessment tool guides them through in-class tasks and the weighting of marks allocated to different parts, as well as constant mediation and discussion of the assessment. The assessment requires visualisation of the different levels of thinking outlined in Bloom's revised taxonomy. The idea is that the assignment is scaffolded in five separate steps: (1) information gathering, (2) critical engagement with the information in groups via the spiderweb activity, (3) organising the information into relational points to answer a historical essay question, (4) a peer review on a colleague's essay and (5) a reflection on the exercise.

Observations

The spiderweb tool process allowed students to understand what exact form of thinking must be applied to an essay for them to create a historical argument based in critical thinking. The spiderweb-building activity in the class was fun and chaotic, and as it was built on a preselection of specific pieces of evidence, this showed the importance of planning and selection in essay building. The critical thinking that went into selecting pieces of information dramatically influences one's argument. Students were in discussion about what kind and level of thinking they needed to do to a piece of information to make it work in an argument, and often the discovery was that they needed to do multiple things to one piece of evidence. This involved a realisation on how levels of thinking build on each other and how critical thinking relies on lower levels of thinking to function at higher levels.

The debates between the students were evidence of their growing awareness of their own voices and how this impacts the argument. The reflections on the process showed an increased awareness on each separate part of the process, which also demystified the process of essay writing. Many students found the exercise difficult, particularly identifying the levels of different thinking, showing the process of critical thinking is hard and requires applied thought.

The demystification of the process seemed particularly important to observe, as this speaks about epistemic access. Even though the exercise is intended to be fun and a bit whimsical, appropriate for classes across the education stages, there is a weight to laying out step-by-step processes. In this process students find themselves engaging explicitly in their own thinking processes, finding their own words.

Conclusion: On critical thinking, materials development and teaching history

This article has attempted to contextualise the difficulties and importance of history teaching in post-1994 South Africa. The necessity of developing critical thinking and voice in teacher education spaces is particularly urgent, as it in these spaces that teachers develop their own agency and capacity to both use and teach these critical skills. There is much more to explore in this field, in both pedagogy and assessment. Kumalo (2018) calls for a pedagogy of 'mutual (in)fallibility':

The need to establish a pedagogical space in which the historical traumas of society are used to advance teaching methodologies which not only respond to these historical traumas but are further used to ensure that the pedagogical environment is one which inspires the students to question their assumptions about those who are framed as Other. (p. 13)

The importance of maintaining academic rigour and voice in this project is part of this proposition by Kumalo. More than this, however, the balance between academic rigour and voice facilitates the critical thinking potential of history. In terms of epistemological access, this opens possibilities it can offer for all students, especially to, as Kumalo calls for, '… question their assumptions about those who are framed as Other'.

Understanding history as power, and history as narrative, is crucial in a country still mired in inequalities and oppressions. This understanding empowers learners to investigate social and economic power structures, spatial geographies, race and gender landscapes that influence their lives. However, they cannot do this without understanding the need for critical thinking and voice in their interpretations of and attitudes towards history.

In this article, I have discussed the issues around teaching of critical thinking in history essays, drawing together various historical thinking and assessment concepts. I have proposed a tool as an example of how these issues can be addressed through both concept and praxis. Using CA and learner-oriented assessment, and breaking down the assignment into disciplinary-oriented steps, this tool made an impact on how students engaged with different thinking levels in terms of constructing a history essay. There are many issues to contend with: socialisation of historical knowledge as something that exists as concrete and objective truth, rather than something that is always filtered through a time, place and person; difficulties of epistemological access in terms of a student positioning themselves in relation to knowledge bodies, particularly in Historically White Universities (HWU) maintaining the validity and reliability of an assessment while keeping it rooted in WTP. There is a clear need for more research into historical thinking and methodology in South Africa in particular and in the Global South more broadly.

Our history and present, our global location lends a specific texture and urgency to the need for students to critically locate themselves and their voices in historical knowledge and historical argument. The struggle for voice and agency is obviously not limited to the history classroom, but the history classroom can be used to sharpen these skills:

At the heart of this is a question of how all students can inhabit and employ their critical thinking, their agency, their own particular perspectives and positionality to understand the world and create historical arguments. These are important for students navigating a complex and difficult world. These skills are necessary beyond the history classroom. I will end with the words of Mumsy Malinga, given during the keynote of 2018 conference of the South African History Teachers Association: We are teaching our students skills. They are survival skills. (Malinga 2018)

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author has declared that no competing interest exists.

Author's contributions

I declare that I am the sole author of this research article.

Ethical considerations

This research was conducted under ethical clearance number H18/10/10. All participant information was collected with confidentiality and is used anonymously, with all identifying markers removed. This is an autoethnographic article in which I draw on observations of my own class, so potential markers of the class itself have also been removed.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

As this article is autoethnographic, no data sets are available.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the author.

References

Anderson, L.W., Krathwohl, D.R., Airasian, P.W., Cruikshank, K.A., Mayer, R.E., Pintrich, P.R. et al., 2013, A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom's, Pearson Education Limited, London, England.

Anonymous Student. (2018, August 20). University of the Witwatersrand [Personal communication].

Bam, J., Ntsebeza, L. & Zinn, A., 2018, Whose history counts: Decolonising African pre-colonial historiography, re-thinking African history, African Sun Media.

Biggs, J. & Tang, C., 2011, Teaching for quality learning at University, 4th edn., Open University Press, Maidenhead, UK.

Biggs, J., 2014, 'Constructive alignment in university teaching', HERDSA Review of Education 1, 5-22. [ Links ]

Carless, D., 2015, 'Exploring learning-oriented assessment processes', Higher Education: The International Journal of Higher Education Research 69(6), 963-976. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-014-9816-z [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education, 2011, Curriculum and assessment policy statement: Grades 4-6 Social Sciences, Department of Basic Education, Pretoria, South Africa.

Department of Basic Education, Republic of South Africa (ed.), 2011a, Curriculum and assessment policy statement - Grades 7-9: Social sciences, Department of Basic Education, Pretoria, South Africa.

Department of Basic Education, Republic of South Africa (ed.), 2011b, Curriculum and assessment policy statement - Grades 10-12: History, Department of Basic Education, Pretoria, South Africa.

Elbow, P., 2000, Everyone can write: Essays toward a hopeful theory of writing and teaching writing, 1 edn., Oxford University Press, New York, NY.

Freire, P., 1996, Pedagogy of the oppressed, Penguin Group, London.

Gee, J.P., 2002, 'Literacies, identities, and discourses', in M.J. Schleppegrell & M.C. Colombi (eds.), Developing advanced literacy in first and second languages: Meaning with power, pp. 159-175, Routledge, Abingdon.

Gennrich, T. & Dison, L., 2018, 'Voice matters: Students' struggle to find voice', Reading & Writing 9(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.4102/rw.v9i1.173 [ Links ]

Godsell, S., 2019, 'Poetry as method in the history classroom: Decolonising possibilities', Yesterday and Today 1-28. https://doi.org/10.17159/2223-0386/2019/n21a1 [ Links ]

Kumalo, S.H., 2018, 'Explicating abjection - Historically white universities creating natives of nowhere?', CriStal: Critical Studies in Thinking and Learning 6(1), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.14426/cristal.v6i1.132 [ Links ]

Lorde, A., 2007, Sister outsider: Essays and speeches, Crossing Press, Feasterville Trevose, Pennsylvania, USA.

Malinga, M., 2018, The history teacher in 21st century South Africa, Cape Town.

McKenna, S., 2010, 'Cracking the code of academic literacy: An ideological task', in Beyond the university gates: Provision of extended curriculum programmes in South Africa, pp. 8-15.

Mezirow, J. & Taylor, E.W., 2009, Transformative learning in practice: Insights from community, workplace, and higher education, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, New Jersey.

Middendorf, J. & Pace, D., 2004, 'Decoding the disciplines: A model for helping students learn disciplinary ways of thinking', New Directions for Teaching and Learning 2004(98), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.142 [ Links ]

Monte-Sano, C., 2012, 'What makes a good history essay? Assessing historical aspects of argumentative writing', Social Education 76, 294-298. [ Links ]

Morrow, W.E., 2009, Bounds of democracy: Epistemological access in higher education, HSRC Press Cape Town, Cape Town.

Ndlovu, S.M., Lekgoathi, S., Esterhuysen, A., Mkhize, N.N., Weddon, G. Callinicos, L. et al., 2018, Report of the history ministerial task team for the department of basic education, Department of Basic Education, Pretoria.

Ramoroka, D. & Engelbrecht, A., 2015, 'The role of History textbooks in promoting historical thinking in South African classrooms', Yesterday and Today 14, 99-124. https://doi.org/10.17159/2223-0386/2015/nl4a5 [ Links ]

Rembach, L. & Dison, L., 2016, Transforming taxonomies into rubrics: Using SOLO in social science and inclusive education, viewed 16 August 2022, from http://scholar.ufs.ac.za/xmlui/handle/11660/3838.

Rust, C., 2001, A briefing on assessment of large groups. The generic centre: Learning and teaching support group, Assessment Series, 32, LTSN Generic Centre, New York, NY.

Seixas, P. & Morton, T., 2012, The big six historical thinking concepts, 1st edn., Nelson Canada, Toronto.

Seixas, P., 2006, Benchmarks of historical thinking: A framework for assessment in Canada, Centre for the study of Historical Consciousness, Vancouver.

Shalem, Y., Dison, L., Gennrich, T. & Nkambule, T., 2013, '"I don't understand everything here … I'm scared" : Discontinuities as experienced by first-year education students in their encounters with assessment', South African Journal of Higher Education 27, 1081-1098. [ Links ]

Tambyah, M., 2017, 'Teaching for "historical understanding": What knowledge(s) do teachers need to teach history?', Australian Journal of Teacher Education 42(5), 35-50. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2017v42n5.3 [ Links ]

Teeger, C., 2015, '"Both sides of the story": History education in post-Apartheid South Africa', American Sociological Review 80(6), 1175-1200. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122415613078 [ Links ]

Wills, L., 2016, 'The South African high school history curriculum and the politics of gendering decolonisation and decolonising gender', Yesterday and Today 16, 22-39. https://doi.org/10.17159/2223-0386/2016/n16a2 [ Links ]

Wineburg, S., 2001, Historical thinking and other unnatural acts: Charting the future of teaching the past, unknown edn., Temple University Press, Philadelphia, PA.

Wineburg, S., 2018, Why learn history, 1st edn., University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL.

Zinn, H., 2005, A people's history of the United States, Harper Perennial Modern Classics, New York, NY.

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Sarah Godsell

sdgodsell@gmail.com

Received: 10 Aug. 2022

Accepted: 13 Sept. 2022

Published: 25 Nov. 2022

1 . This is particularly true in an emergent democracy where we are unravelling the power structures that have positioned some histories over others and have voiced some narratives while silencing others. We write from who and where we are. This involves a myriad of different, and shifting, sets of identities, positionalities and knowledges (Lorde 2007).

2 . This was observed through history classes in Bachelor of Education programmes at the University of Johannesburg in 2016 and 2017 and at the University of Witwatersrand in 2018 and 2019. The observation of these classes was cleared by the universities' ethical committees.

3 . This was a student who wishes to remain anonymous from a Senior Primary History III content class at the University of Johannesburg.

4 . The research around students' responses and the implementation of this example task will be published in a later article.

5 . Historical thinking and critical thinking are not interchangeable, and I do not use them interchangeably in this article. Critical thinking is essential to historical thinking, and this is the skill that is most mobile between disciplines and most essentially deployed in, and taught through, writing.

6 . Another constraint that we have in South Africa is language: if we are consistently using specific verbs, as suggested by Biggs, to convey expectations, educators must be very careful that the understanding of those verbs is exceptionally clear to avoid implicit or tacit expectations, or 'situated meanings' (Gee 2002). While this is a potential issue in the use of verbs, it is not by any means limited to CA. The language and clarity of all assessments need to be mediated (Shalem et al. 2013). And perhaps using carefully selected and well-mediated verbs repeatedly could achieve this necessity. For me, a key element in solving this puzzle is effective class mediation to get the students to a point where they understand what historical argument is, what critical thinking is and where their own voices are in that process.

7 . This is another constraint on assessment - effective mediation and scaffolding require in-class time, which is precious. I return to this problem in my conclusion.