Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Childhood Education

On-line version ISSN 2223-7682

Print version ISSN 2223-7674

SAJCE vol.12 n.1 Johannesburg 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v12i1.1089

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Early Childhood Care and Education teachers' experiences of integrating the activities of the national curriculum framework into themes

Cynthia Z. ZamaI; Nontokozo MashiyaII

IDepartment of Education, Faculty of Early Childhood Education, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

IIOffice of the Vice Chancellor, University of Zululand, Kwa-Dlangezwa Campus, Empangeni, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Integrating teaching and learning activities around the selected themes was acknowledged as an effective way to manage learning in the Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE) sector. It was also ensured for the desired results and highest opportunity to prepare young children for school readiness in the South African National Curriculum Framework (NCF).

AIM: The aim of this study was to explore ECCE teachers' experiences of integrating activities from the six early learning developmental areas (ELDAs) of the NCF into the selected themes.

SETTING: This interpretive case study was conducted with six purposively selected ECCE teachers from three centres that followed the guidelines of the NCF for the development of young children in the Umbumbulu rural area in KwaZulu-Natal province.

METHODS: The study was framed within the transformative learning theory and qualitative data were generated using semi-structured interviews and document analysis that were inductively analysed using the data analysis spiral.

RESULTS: The findings show integration as a collaborative venture for teachers to interpret the NCF, select themes, and identify and integrate activities from the six ELDAs when planning lessons. Natural, indigenous themes and man-made resources were used to overcome the shortage of teaching resources. Challenges occurred from the lack of play resources and the support from department officials.

CONCLUSION: This study recommends more teamwork for ECCE teachers to understand the objectives of the NCF for purposeful planning to meet young children's learning needs and school preparedness in the ECCE sector. Further research is recommended in the ECCE sector.

Keywords: integration; National Curriculum Framework; Early Childhood Care and Education teachers; young children; rural centres.

Introduction

Converging the need to care and education as the foundations for lifelong learning led to the development of the National Curriculum Framework (NCF) for children from birth to 4 years in South Africa (Department of Basic Education [DBE] 2015; Ebrahim & Irvine 2012). The NCF strengthened the global concern to school readiness and the curriculum aligned to young children's experiences as the foundations for early learning (Campbell-Barr & Bogatic 2017; Hannaway et al. 2019). Planning became the meaning-making opportunity for Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE) teachers to share knowledge and ideas about how young children learn. Thus, Meier and Marais (2018) highlighted the importance of teaching and learning activities that are integrated into the selected themes and resources for the holistic development of babies, toddlers and young children. However, ECCE teachers in the rural centres are known for their poor planning skills while teaching material and play resources are lacking (Aubrey 2017; Kirsten 2017; Ntumi 2016; Somantri et al. 2019; Van der Walt, Swart & De Beer 2014).

In this research, the integration of activities into the selected themes is studied as the implementation of the NCF for the development of 3-4-year-olds commonly known as young children that are advancing further to the Reception year (Grade R) class (DBE 2015). Integrating activities into the selected themes is considered as the new planning experience on the basis of the school readiness components, such as creative thinking and problem-solving connected in the six early learning developmental areas (ELDAs) that are used as subjects in the NCF document. It sets the standards to ensure that young children meet the formal schooling needs (Evans 2013). The study throws light on how ECCE teachers identify teaching and learning activities from each ELDA to integrate into the selected themes.

While Ntumi (2016) identified ECCE teachers to be unable to understand the early childhood curriculum content in the Cape Coast Metropolis, Bitok et al. (2014) emphasised the significance for teachers to comprehend curriculum content when connecting teaching and learning activities. Thus, teachers are acknowledged as the significant resources for the proper implementation and the achievement of the curriculum goals (Ebrahim 2012). They are accredited as creative thinkers and role-players that bring their abilities together for the development of good learning opportunities to overcome challenges that can be encountered during the planning process (Bitok et al. 2014; Mezirow 2000). Moreover, Drake and Reid (2018) examined the best teacher strategy to bring their experiences together, make sense of the environment and provide equal learning opportunities to achieve the objectives of the curriculum. Where thematic related teaching and learning resources were scarce, teachers reached out to the communities for assistance to waste collection to be used for play resources development (Drake & Reid 2018; Soni 2015).

This study contributes to the appropriate learning experiences for young children after the introduction of the curriculum framework for children from birth to 4 years in South Africa. It is the exploration of the transformation process encompassing the official standards to reduce education differences in the ECCE sector. Literature reviewed in this regard is discussed below.

The reviewed literature

Integration of the activities into selected themes

The integration of teaching and learning activities around the selected themes, also known as the thematic approach, is the connection made whereby several learning objectives of the curriculum merge (Bjorklund & Ahlskog-Bjorkman 2017; Varun & Venugopal 2016). Various teaching activities are prepared to link to one another in order to avoid the unclear and incoherent nature of learning as the invention of positive childhood development (Ashley-Cooper, Van Niekerk & Atmore 2019; Meier & Marais 2018). Where the selected theme is transport, teaching and learning activities and the resources are linked to transport (Zin et al. 2019). Subject areas and content topics are incorporated into the selected themes and play resources for easiness to learn (Somantri et al. 2019). The attempt is to develop the highest scope of learning that creates meaningful and interesting learning environment.

Drake and Reid (2018) identified the integration of activities into the themes as the joint venture for teachers to determine what young children have to know, do and become at the end of each particular year. Teachers usually spend much time at the beginning of the year to identify the learning purpose and discuss how they want young children to achieve the outcomes of the designed curriculum (Meier & Marais 2018). After examining the curriculum document, they brainstorm the activities and select themes in line with young children's development (Biersteker et al. 2016; Soni 2015). They strive for the best in all the aspects to bring fun and joy into young children's play world so that they can learn. Bento and Dias (2017) added that real-life experiences, children's age, level of development and the suitable style of learning are taken into consideration.

Meier and Marais (2018) asserted that in the early grades, teachers work hard to minimise chances of offensive themes getting exposed to any cultural group of children. Therefore, multicultural themes such as my body, my family and many others that encourage all young children to understand and accept themselves are encouraged (DBE 2011). Rudolph (2017) highlighted that attention is also given to the immediate surroundings where themes and resources such as plants, animals, soil, water and weather can be available in the environment.

Planning for teaching in the related context

Evans (2013) raised the importance of meeting the formal school needs in the ECCE. In the South African context, Moodley (2013) studied the implementation of the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) and acknowledged its clarity, clear guidelines and the examples of teaching and learning activities and resources to be used for the development of learners when they begin school. The Grade R Life Skills CAPS comprises the suggested topics and the examples of relevant themes for the development of learners (DBE 2011). The 12 randomly selected themes are presented in Figure 1 as the examples of topics and themes to integrate Grade R activities as included in the CAPS.

Grade R teachers integrate teaching and learning activities into the suggested themes while relevant teaching and learning resources are recommended. Thus, meaningful connections between selected themes, activities and play resources are properly guided (Reetu, Renu & Adarsh 2017). Figure 2 includes the examples of teaching and learning activities from the Grade R subjects connected to a theme 'my body.'

In Grade R, teachers identify and connect activities from Life Skills, Language and Mathematics activities to the themes and resources. Thus, young children's bodies, people and other suggested play resources are used for teaching. The intents of the ECCE curriculum are provided below.

The intents of the National Curriculum Framework

The NCF for children from birth to 4 years is identified as a flexible tool that encourages team work for adults and teachers to apply their knowledge in the provision of meaningful learning to young children under their care (Murris 2019). Therefore, high-quality experience is the development of knowledge adjusted within the local context of a child (DBE 2015; Rudolph 2017). The National Early Learning and Development Standards for children from birth to 4 years released in 2009 became the first step towards the development of the NCF (DBE 2009; Ebrahim 2012). National Early Learning and Development Standards was used as a teaching resource that was later identified as unsuitable for social transformation, quality and equality that was lacking in the South African ECCE sector (Atmore, Van Niekerk & Ashley-Cooper 2012). Therefore, the NCF viewed young children in relation to their social development and culture (DBE 2015; Ebrahim & Irvine 2012). It includes the developmental guidelines, the examples of teaching and learning activities and the guidelines for assessing infants, toddlers and young children. Evans (2013) asserted that assessment judges if young children are ready for the next stage. Instead of subjects, six ELDAs (well-being, identity and belonging, communication, exploring mathematics, creativity and knowledge, and understanding of the world) including teaching and learning activities are to be integrated into the selected themes that are not included in the document. Early learning developmental areas and the examples of activities are provided next.

-

Well-being

Well-being is the first ELDA of the NCF to be integrated into all other five ELDAs (DBE 2015). Well-being is developed on the basis of the South African Constitution for the right to health and safety to every child (UNESCO International Bureau of Education 2017). It is associated with the Life Skills (personal and social well-being) in the Grade R curriculum content. Therefore, young children become privileged to tell stories, recite rhymes, and show and tell about health and hygiene in the environment that is safe for them to play and learn (Azzi-Lessing & Schmidt 2019; Berry & Malek 2017). The content also indicates the recognition of social, physical, cognitive and psychological development of children (Rudolph 2017). Young children strengthen their well-being as they interact with each other while moving up and down inside and outside the classroom, playing with relevant and safe resources (Gill 2009).

-

Identity and belonging

In identity and belonging, young children are guided to feel proud of themselves as members of their societies (DBE 2015; Ebrahim & Irvine 2012). Leggett and Ford (2016) presented identity and belonging as a life skills opportunity for group activities and social interactions equipping children with the appropriate decision-making skills early in life. Young children are guided to talk, sing songs, and draw while playing and making sense of their surroundings.

-

Communication

Communication is the third ELDA designed for the development of early language skills needed in the formal school (Ebrahim & Irvine 2012). Young children develop communication skills in a print-rich environment through reading, rhyming, singing, writing, telling stories and playing to learn (Maluleke, Khoza-Shangase & Kanji 2019). Vorster et al. (2016) suggested the development of communication skills as very challenging where teaching and play resources for language development are not properly organised.

-

Exploring mathematics

In exploring mathematics, young children solve mathematical problems and play with shapes and numbers to develop basic mathematical skills (Samaras 2011). Kortjass (2019) suggested that early mathematics has to be fun and stimulating while connections are made to the child's environment. Therefore, there is a potent connection between the classroom environment and the everyday life of young children. Young children also count, recognise relationships, extend patterns, sort, match and solve problems through play (Feza 2012; Zosh et al. 2017). However, Feza (2012) argued that solid foundations have to be laid for lifelong mathematics learning, especially for underprivileged young South Africans who are affected by social inequalities.

-

Creativity

Belgi (2018) defined creativity as the kind of imagination shaped to produce the outcomes of value and uniqueness. In the NCF, creativity is included as the fifth ELDA for young children to develop new and useful ideas as solutions to challenges and problems at their level (DBE 2015; Ebrahim & Irvine 2012). As a result, young children are encouraged to be imaginative and creative with the appreciation of arts. Creative skills develop as children ask questions, find solutions, make up songs and rhymes, draw, dance and dramatise in order to explore and experiment in a playful way (DBE 2011).

-

Knowledge and understanding of the world

The last ELDA, knowledge and understanding of the world, relates to young children's everyday experiences with their families, homes, other people and all the physical surroundings. Knowledge and understanding of the world also links to life skills subject such as geography, history, science and languages (DBE 2009). Consequently, young children learn about the world with attention to objects and all living things that can be examined. Clampett (2016) suggested the inclusion of technology for young children to design, explore and investigate lifelong benefits through play. In the text section we present the research questions that guided this research study.

Research questions

The creation of a meaningful and interesting atmosphere for young children's development depends on planning to integrate activities into the selected themes. Hence, the following research questions guided the research study:

-

What are the themes that ECCE teachers use to integrate young children's activities?

-

How do ECCE teachers integrate teaching and learning activities from the ELDAs of the NCF into the selected themes?

The theoretical bases of the study are discussed next.

The theoretical bases of the research study

This study was framed within transformative learning theory (TLT) which was first introduced by Jack Mezirow in 1978 as a description of how adult learners interpret, confirm and reformulate the meaning of their experiences (Cranton 2006:22). Mezirow framed his theory as a perspective transformation, realising reflections as the most significant component of learning in adulthood as they allow self-directed people to challenge their own thinking, and interpret their experiences to advance themselves and others (Cox & John 2016; Mezirow 1991, 2000). Mezirow identified transformative learning as an act of thinking, preparedness, willingness and the desire to engage in a new learning process (Taylor & Cranton 2013). In relation to this study, TLT is greatly influenced by Jurgen Habermas' (1971) theory of communicative action which highlights human interest to reach social agreement and promotes individual growth from which communicative and emancipatory knowledge arises (Calleja 2014).

Mezirow (2000:19) identified learning as the strengthening of the frames of reference and the transformation of the habits of mind. The frames of reference and the habits of mind are similarly described as the interpretation of meaning to the experiences that guide actions. Mezirow (2000) also exposed transformation as a collaborative meaning-making practice for people to share experiences in the learning process (Taylor & Cranton 2013). During the process, adult learners become inspired to strengthen the environmental knowledge, gain new information and extend their skills.

The South African ECCE sector has undergone a process of transformation as the provision of care and education to prepare young children for school (Murris 2019). The NCF specifies the planning, education provision and assessment to be organised around the six ELDAs to promote equitable learning opportunities for all children (DBE 2015). Early Childhood Care and Education teachers from the rural centres were therefore exposed to the new learning experience as a result of the integration of the activities from the ELDAs of the NCF into the selected themes. That happened after the history of neglect and lack of planning guidance to prepare young children from the rural settings for school (South African Early Childhood Review 2019). Early Childhood Care and Education teachers in this research study appear as self-directed adults aiming to learn for the promotion of the effective guidance as initiated in the TLT (Mezirow 2000; Ritz 2010). They shifted their thinking to embrace change regardless of all the challenges (Atmore 2018). Moreover, they considered learning the NCF as the meaning-making opportunity for the development of young children that are school ready (Mezirow 1997, 2000). Hence, the prominence of readiness is highlighted within the education policy (Evans 2013). The research methods and the design are presented below.

The research methods and the design

This research study strives for self-determination, openness and flexibility (Cohen, Manion & Morrison 2018; Creswell 2014). Accordingly, the qualitative approach together with the case study design was used to facilitate expedient data generation from the relevant sources. The study adopted the interpretive paradigm for the knowledgeable participants to share their experiences and the realities about the phenomenon (Cohen et al. 2018; Creswell & Poth 2018). After the development of the NCF for children from birth to 4 years, rural ECCE centres discovered the need for change. Thus, a purposive sampling was used to select six ECCE teachers from the three ECCE rural centres of the Umbumbulu area in the KwaZulu-Natal province that transformed to the guidelines of the NCF to prepare young children activities. that are integrated. The teachers worked with the ELDAs of the NCF instead of the three normal teaching subjects (Mathematics, Language and Life Skills). These teachers were guaranteed confidentiality and anonymity. Pseudonyms were used for their names and their centres.

The data generation process started after receiving the ethical clearance from the university, permission from the Department of Social Development (DSD) and consent from the participants indicating their willingness to participate in the study. Data were generated using semi-structured interviews, and personal (lesson plan and theme book) and official planning documents (NCF) used by the participants. These were scanned and analysed for more evidence on the phenomenon. All the interview questions were translated from English to IsiZulu for the participants to freely use their language of choice. Each interview that lasted for about 45 min was recorded for the correctness of information. Semi-structured interviews allowed the participants to freely talk about their practices (Du Plooy-Cilliers, Davis & Bezuidenhout 2018).

All the participants were women, with ages ranging between 23 and 52 years. Although previous studies specified that many ECCE rural teachers are un- or under-qualified with limited teaching skills (Kirsten 2017; Ntumi 2016), most of the participants had the Early Childhood Level 4 qualification, while others were still studying in this field. Their teaching experience ranged from 2 to 15 years. Ms Zulu, who was the oldest, had 11 years' teaching experience, while the 37-year-old Ms Ngcobo had the longest 15 years' teaching experience.

After the interviews and document analysis, the task of making sense of the data generated, reading, organising and interpreting began (Du Plooy-Cilliers et al. 2018). Raw data from the semi-structured interviews and the scanned planning documents were organised into one file to make transcriptions easier. The researcher read, re-read and manually transcribed the data. This process helped the researcher make sense of the data. The transcribed data were coded and fused into themes. The data were also inductively analysed using the data analysis spiral as suggested by Creswell and Poth (2018). They identified the five steps of the data analysis spiral as organising data, reading to find emerging ideas, classifying codes into emerging themes, assessing interpretation and data presentation. The following section discusses the findings of the research study.

Findings and discussions

The rural ECCE transformed into the guidelines of the NCF for the planning of teaching and learning activities which were integrated into selected themes. Six purposively selected participants responded to the interview questions and shared the planning documents.

Four themes that emerged from the semi-structured interviews and document analysis are desirable learning opportunity, collaborative learning effort, the formulation of the instruction plan and the challenges encountered.

Theme 1: Desirable learning opportunity

Meier and Marais (2018) highlighted the importance of themes that are meaningful, funny, interesting and part of young children's daily lives. Data generated from the semi-structured interviews were supported by the theme books and the lesson plans that the participants presented. When asked about the themes used to integrate teaching and learning activities for young children, the participants provided examples of themes and also how those themes were selected. Mrs Y from Centre C said:

'We consider the experiences that young children bring to school, what we think they know and interesting to them for them to learn. We usually consider themes such as me, my body, my family, my home, my classroom, my school at the beginning of the year and further develop to plants, animals and transport. "Every year we sit as staff, select themes that relate to the teaching and learning resources that can be easily available for young children to play and learn". We usually identify ten to twelve themes per year.' (Ms Y, Centre C)

It was evident from the excerpt above that theme selection is a desirable learning opportunity to think about the experiences that young children bring to school and the available teaching and learning resources for young children to learn better. As stated below, the participants also considered pre-planned themes from their reliable sources. The following excerpt clarifies theme selection in Centre B:

'In our centre we use themes that are included in the theme book that I was given by the Non-Governmental Organisation (NGO), Training Resources in Early Education (TREE) when I started working in this centre in 2005. Ten themes in the theme book are me, my home and my family, my town and my community, water, winter and fire, ways of travelling, farming, arts and crafts around us, going to big school and festivals. We integrate teaching and learning activities from the six ELDAs into those themes.' (Ms D, Centre B)

What the participant mentioned in Centre B was also similar to what one Centre A participant said:

'We use themes from the CAPS Grade R IsiZulu life skills document. At the beginning of the year we sit together as staff to select twelve themes that are included as topics in the document. We mostly identify themes that are natural to easily identify teaching and play resources around us. We usually include myself (mina), my body (umzimba wami), my family (umndeni wami), weather, water (amanzi), plants (izitshalo), at school (esikoleni), vegetables (imifino) and farm animals (izilwane ezifuywayo) for meaningful interactions where teachers and learners talk about what they know. We use any related available resources, make resources and keep them safe to re-use.' (Ms Z, Centre A)

The participants' responses showed that pre-planned themes were also used in two centres. A theme book including 10 themes provided by the NGO was used in Centre B and Centre A. Themes were selected from the list of themes included in the CAPS Grade R Life Skills document. The responses also showed that the selected themes allowed the meaningful interactions for children to talk about what they know. It was evident that immediate surroundings are considered as the themes also relate to plants, animals, soil, water and weather where teaching and learning resources are natural and easily available in the environment (Rudolph 2017). As mentioned above, most themes relate to natural and indigenous resources that are available in the environment. We also discovered from the data generated that ECCE teachers were flexible regarding the number of themes to be used. Therefore, 10-12 suitable themes were selected in all the three centres. Although pre-planned themes were used, the participants in all the three centres raised that at the beginning of the year they work together in all the centres to discuss the themes and identify teaching and learning activities. The participants presented their practices as collaborative learning opportunity.

Theme 2: Collaborative learning opportunity

Collaborative learning opportunity emanated from the interviews with the participants who shared their knowledge and experiences which yielded successful outcomes to read and identify teaching and learning activities from the six ELDAs. This was evident as the participants started reading the NCF in teams. The participants used different words to confirm Steyn's (2017) idea that collaboration among teachers influenced learning, growing and development for people to transform. During the semi-structured interviews all the participants identified the importance of each other in organising. One participant said:

'Only two of the ten teachers in our centre attended the NCF training organised by the Department of Basic Education. Immediately after its introduction, we made time in our centre to read the content of the NCF and to identify activities from the ELDAs together.' (Ms C, Centre A)

The same positive attitude was evident among Centre C teachers:

'I was the only one who attended half day NCF training but, I was able to share what we learned with all other teachers as we read the NCF together. It was surprising that other teachers ended up sharing what they know and we learned more from each other. We met in the afternoon from Monday to Thursday to learn.' (Ms K, Centre C)

Similar to Centre A and Centre C teachers, the participant from Centre B mentioned that unpacking the NCF to identify the activities was not an individual responsibility. The participant said:

'Immediately after the NCF was introduced we made time for all to learn together. The emphasis became more to learning the six ELDAs and theme selection. As we teach young children, we identified what was relevant to them.' (Ms D, Centre B)

From the extracts above, it became evident that the participants collaborated to share experiences and knowledge to learn the NCF as they were not properly trained by the DBE for curriculum implementation. The researcher could associate what occurred with Mezirow's statement in his TLT that people transform as they collaborate to share skills and thinking to engage in a new learning experience (Mezirow 1991, 2000). When the researcher examined the NCF it was realised that team work was the vision of DBE in the document. It was also realised that teachers and adults working with young children have to work in teams and share ideas to make it meaningful to them (DBE 2015; Ebrahim & Irven 2012).

When questioned further about the activities, the participants clarified that after sharing their experience, they easily identified teaching and learning activities to integrate into the selected themes from each ELDA of the NCF. Mrs C from Centre A said:

'"In communication"! we learned that it is mainly language that develops as young children play. The activities include story reading, rhyming, singing songs, and speaking linked to themes. In exploring mathematics, young children count small numbers and play with shapes and colours. They also play with sand and water, play games with toys to solve problems at their level while they are safe to learn.' (Ms C, Centre A)

Ms B from the same centre added that:

'"In Well-being", the activities are similar to the life skills in Grade R. The importance of safety and good health is emphasised as children tell stories, show, and tell about health and hygiene. As teachers we help children to learn about life. We also talk about cleanliness as children play with relevant toys to learn.' (Ms Z, Centre A)

The following participants commented about the activities of the other two ELDAs, 'identity and belonging' and 'knowledge and understanding of the world':

'"In Identity and belonging" and "Knowledge and understanding of the world" activities include opportunities for children to talk about themselves and about things happening in the world around them. In the "Identity and belonging" young children have to talk [for instance] about families or the weather and tell stories they know about their gender and also relate to themes. They talk about what they do, imitate other people, and also play to learn using safety toys. We plan excursions for children to learn about the selected themes and about the world outside the centre.' (Ms N, Centre B)

Ms Y from Centre C responded to the activities of Creativity and said:

'In creativity young children draw, paint, cut, paste, sing and play in the environment that is safe to learn about a particular theme. We also include make-believe play activities, guide children to use scissors and to use play dough to make different shapes. These help them to develop small muscles and be healthy.' (Ms Y, Centre C)

What the participants stated above is the indication that all the centres were able to identify appropriate teaching and learning activities as they related them to their earlier knowledge of their subjects. The occurrence resonates with Mezirow's (1991, 2000) theory which suggests that previous experiences guide future actions and play a vital role in the transformation process as our memories are actively engaged in the identification of previously learned experiences (Hatherley 2011; Mezirow 1991). After theme selection and identifying teaching and learning activities, the participants indicated that they formulated the instructional plan to present the integrated activities.

Theme 3: The formulation of the instruction plan

The teachers presented lesson planning as the important aspect of thematic teaching. We could read the lesson planning decisions from the lesson plan and the theme book that the participants presented. Although the participants expressed themselves differently, data showed that they had similar understanding of planning the lesson. One participant said:

'We integrate the activities from all the ELDAs into the theme to achieve the objective of the lesson. Our theme for the week is "farming". We integrate the activities into the theme and plan for children to talk about farming, draw or paint farm animals, sing songs, recite rhymes, talk, count and colour farm animals. In our centre we also make our own resources to teach as I didn't get the relevant story and I decided to write my story about farm animals.' (Ms K, Centre C)

From the excerpt above, we realised that participants integrate teaching and learning activities from all the ELDAs into one lesson while creative skills to develop theme-related story were also noted. Teacher creativity was also highlighted from another participant from Centre B which was also supported by the planning document. The participant said:

'When planning the lesson, we write down the selected theme and the identified teaching resources. Teachers teaching the same group of children plan together. If the theme is my body, for Well-being, identity and belonging and communication we plan stories about my body, rhyme, talk and make demonstrations about keeping bodies clean. To explore mathematics, we count body part and we draw, cut or paint in creativity. We can also use playdough to make body parts. For the Knowledge and understanding the world in the fantasy play: children dress up to cover their bodies and during free play they run and play for physical development. The resources for that theme include story book, cardboard, counters, paint, papers and scissors. I thereafter observe children working as individuals or in groups.' (Ms D, Centre B)

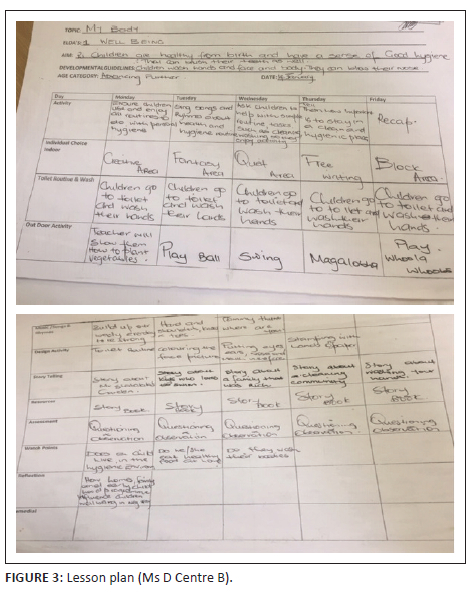

The excerpts above showed that integrating activities is done by the teachers together mainly to share ideas and achieve the objectives of the curriculum. Data also verified the importance of teaching and learning resources in the best interest of young children. Lesson plan to support what Ms D said is presented. One-day lesson planning is shown in Figure 3.

The excerpt and the lesson plan above displayed teaching and learning activities from all the themes as integrated into the selected themes. We discovered that the lesson plan included age category (young children 3-4 years), date, aim of the ELDA, activities, individual choice activities, outdoor activities, the ideas for assessment and the reflections. We could also read from the above lesson plan that bodies as they were available were used as teaching and play resources including whoola hoops, balls and swings for physical development. Although the findings revealed that the participants reflected at the end of the lesson, we can see in this particular lesson plan that the reflections were not included. Therefore, the findings agree with Yin's (2009) assertion that it sometimes happens with the personal documents that the required information is incomplete.

It emerged from the discussions that a lesson plan template was provided by the NGO that supports ECCE centres in the area. There was no evident of further support from the DBE that introduced the NCF to ECCE rural centres. Therefore, other ECCE teachers presented challenges that affected their planning practices.

Theme 4: The challenges encountered

Vorster et al. (2016) specified the importance of play and the appropriate resources for the development of young children. However, the findings of this study revealed that challenges including the scarcity of teaching resources and the support from the Department of Basic Education contributed negatively to the integrated planning of teaching and learning activities around the selected themes. These findings were supported by the statements from various participants who confirmed that challenges were experienced in their ECCE centres. One participant presented her experiences and said:

'Although we always try very hard to organise teaching and play resources, most resources like puzzles and reading books are scarce and very expensive for them. We don't afford to buy all the play resources as we are still not funded and rely only on the school fees paid by parents. Sometimes we use stories that are not related to the selected themes and we compromise.' (Ms D, Centre B)

There is evidence of a shortfall of teaching and learning resources in some ECCE centres. That made the participants to reflect if the rural child is still deprived of good education. Another participant said:

'In our centre we try very hard to make our own teaching and play resources to teach but we I think we need more skills to make this better. Look, there are no wheels on the toy cars that we made! (laughing). We utilise the little we have but it is not easy for us to share our skills with other teachers in the area as we try but not perfect. We also make sure many themes that we select allow to use resources that are available in the environment like bodies and plants that children can always see.' (Ms K, Centre C)

The participants alluded to some essential aspects affecting equity that was lacking in the ECCE sector. We noted the teachers' efforts to develop proper lessons. However, more assistance as resources and creative skills to make better resources was identified. These findings gained support from the literature that assumes that play resources such as reading books, puzzles, building blocks and matching cards are limited in many rural ECCE centres (Aubrey 2017). Other participants were concerned about the support from the DBE. Another participant said:

'It was unfortunate that I haven't seen any Department officials that provided the NCF. I was supported by the NGO's and other colleagues in the centre when planning. I thought they were going to come back to see if the NCF was properly implemented for teaching.' (Ms N, Centre B)

The findings revealed that rural ECCE centres expected the support from the Department of Basic Education ECCE officials because the NCF was a new experience to them. The findings above were conflicting with the purposes of the DBE that teachers and adults are the key role-players and meaning makers of the NCF in the ECCE sector. Hence, ECCE teachers accentuated transformation that happened to them.

The above themes developed in the attempt to explore the integration of teaching and learning activities around the selected themes for young children in the rural ECCE centres. The findings showed that rural ECCE centres transformed to the NCF guidance for the appropriate teaching and learning activities and selected themes that are relevant to young children (3-4 years), although there are also some challenges affecting them. The strengths and the limitations of the study are discussed next.

Strengths and limitations

This research study is expected to benefit teachers and adults working with young children, especially those in the rural ECCE centres. The study presents the realities of the context identified with some challenges in the teaching of young children. However, the most important limitation lies in the fact that a case study research was limited to the three ECCE centres that transformed to the guidelines of the NCF for young children's development and preparation for school. This is a very small sample size representing a very large population of the Umbumbulu area in the KwaZulu-Natal province, South Africa, to whom the results cannot be generalised.

Conclusion

The study findings revealed that ECCE rural centres transformed to the guidelines of the NCF for the planning of teaching and learning activities that are integrated. Therefore, thematic teaching was explored as a new experience to integrate teaching and learning activities from the ELDAs of the NCF into the selected themes. The researchers discovered that ECCE teachers collaborated to share ideas and experience to select themes, identify teaching and learning activities and plan the lesson. The findings made it clear that team work helped teachers to realise that activities from the ELDAs were similar to the activities of three Grade R subjects. When planning the lesson, teaching and learning activities from all the six ELDAs of the NCF were integrated into one lesson and connected into a selected theme and to the teaching and play resources. The participants highlighted the importance of natural themes and the indigenous resources that were available in the environment and in the ECCE context. However, teaching and learning resources were scarce without any support from the DBE.

This study contributes to the small corpus of research in the ECCE after the development of the NCF for children from birth to 4 years. The importance to share more experiences and skills for the development of young children is highlighted. The recommendations of the study are discussed next.

Recommendations

This research study recommends further collaborations with communities for ECCE rural teachers to further achieve the objectives of the NCF. This can also be an opportunity to organise workshops and trainings in the area to share creative skills to make own resources using available waste. Early Childhood Care and Education teachers could also get further support from the parents as they contribute to their children's development. Collectively, natural and indigenous resources can be identified in the environment for young children to see, touch, play and learn the activities that are integrated. Further research in the planning of teaching and learning activities in the ECCE is also recommended.

Acknowledgements

The study was the contribution to Teacher Education for Early Childhood Care and Education Project (TEECCEP) as the Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) initiation to the development of Early Childhood Education (ECE) Discipline at University of KwaZulu-Natal, School of Education, Edgewood Campus. Rural Early Childhood Care and Education teachers positively contributed their planning knowledge to its development.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Authors' contributions

This article was developed as part of the first authors PhD study. Both authors (C.Z.Z. and N.M.) contributed equally to the research development. However, N.M. was allocated as the supervisor of the study.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance to conduct this study was obtained from the University of KwaZulu-Natal, Humanities and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee (No. HSS/1668/018D).

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

References

Ashley-Cooper, M., Van Niekerk, L.V. & Atmore, E., 2019, Early childhood development in South Africa: Inequality and opportunity, University of Cape Town, South Africa.

Atmore, E., 2018, 'An interpretive analysis of the early childhood development policy trajectory in post-apartheid South Africa', PhD Dissertation, Stellenbosch University Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Atmore, E., Van Niekerk, L. & Ashley-Cooper, M., 2012, 'Challenges facing the early childhood development sector in South Africa', South African Journal of Childhood Education 2(1), 120-139. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v2i1.25 [ Links ]

Aubrey, C., 2017, 'Sources of inequality in South African early child development services', South African Journal of Childhood Education 7(1), a450. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v7i1.450 [ Links ]

Azzi-Lessing, L. & Schmidt, K., 2019, 'The experiences of early childhood development home visitors in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa', South African Journal of Childhood Education 9(1), a748. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v9i1.748 [ Links ]

Belgi, R., 2018, Creative learning in the early years: Nurturing the characteristics of creativity, University of East London, United Kingdom.

Bento, G. & Dias, G., 2017, 'The importance of outdoor play for young children's healthy development', Porto Biomedical Journal 2(5), 157-160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbj.2017.03.003 [ Links ]

Berry, L. & Malek, E., 2017, Caring for children: Relationships matter. South African Child Guage, Children's Institute, University of Cape Town, South Africa.

Biersteker, L., Dawes, A., Hendricks, L. & Tredoux, C., 2016, 'Center-based early childhood care and education program quality: A South African study', Early Childhood Research Quarterly 36, 334-344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2016.01.004 [ Links ]

Bitok, E.C., Tonui, B., Chepsiror, P. & Too, J., 2014, 'Resource capacities supporting thematic approach in teaching ECDE centres in Uasin Gishu County', International Journal of Education Learning and Development 2(5), 78-86. [ Links ]

Björklund, C. & Ahlskog-Björkman, E., 2017, 'Approaches to teaching in thematic work: Early childhood teachers' integration of mathematics and art', International Journal of Early Years Education 25(2), 98-111, https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2017.1287061 [ Links ]

Calleja, C., 2014, 'Jack Mezirow's conceptualisation of adult transformative learning: A review', Journal of Adult and Continuing Education 20(1), 117-136. https://doi.org/10.7227/JACE.20.1.8 [ Links ]

Campbell-Barr, V. & Bogatic, K., 2017, 'Global to local perspectives of early childhood education and care', Early Child Development and Care 187(10), 1461-1470. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2017.1342436 [ Links ]

Clampett, B., 2016, Quality early childhood development centres: An exploratory study of stakeholder views, University of Cape Town, Cape Town.

Cohen, L., Manion, L. & Morrison, K., 2018, Research methods in education, 8th edn., Routledge Falmer, London.

Cox, A.J. & John, V.M., 2016, 'Transformative learning in postapartheid South Africa: Disruption, dilemma, and direction', Adult Education Quarterly 66(4), 303-318. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741713616648376 [ Links ]

Cranton, P., 2006, Understanding and promoting transformative learning: A guide for educators of adults, Canadian Journal of University Continuing Education, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA.

Creswell, J.W., 2014, A concise introduction to mixed methods research, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Creswell, J.W. & Poth, C.N., 2018, Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches, Sage, California.

Department of Basic Education, 2009, National early learning and development standards for children birth to four years (NELDS), Department of Basic Education, Pretoria.

Department of Basic Education, 2011, Curriculum and assessment policy statement, Grades R-3, IsiZulu, Life Skills, Department of Basic Education, Pretoria.

Department of Basic Education, 2015, The South African National curriculum framework for children from birth to four, Government Printers, Pretoria.

Drake, S.M. & Reid, J.L., 2018, 'Integrated curriculum as an effective way to teach 21st century capabilities', Asia Pacific Journal of Educational Research 1(1), 31-50. https://doi.org/10.30777/apjer.2018.1.1.03 [ Links ]

Du Plooy-Cilliers, F.C., Davis, C. & Bezuidenhout, R.-M., 2018, Research matter, Juta, Cape Town.

Ebrahim, H. & Irvine, M., 2012, National curriculum framework birth to five, Department of Basic Education, Social Development and Health, supported by UNICEF, Pretoria.

Ebrahim, H.B., 2012, 'Foregrounding silences in the South African National Early Learning Standards for birth to four years', European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 22(1), 67-76. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2012.738869 [ Links ]

Evans, K., 2013, '"School readiness": The struggle for complexity', Learning Landscapes 7(1), 171-186. https://doi.org/10.36510/learnland.v7i1.636 [ Links ]

Feza, N.N., 2012, 'Can we afford to wait any longer? Pre-school children are ready to learn mathematics', South African Journal of Childhood Education 2(2), 58-73. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v2i2.12 [ Links ]

Gill, S., 2009, Education for well-being: Conceptual framework, principles and approaches, viewed 08 June 2018, from http://www.ghfp.org/…/Gill09-Conceptualframework-EducationWEllbeing.pdf.

Habermas, J., 1971, Knowledge and human interests, Beacon Press, Boston, MA.

Hannaway, D., Govender, P., Marais, P. & Meier, C., 2019, 'Growing early childhood education teachers in rural areas', Africa Education Review 16(3), 36-53. https://doi.org/10.1080/18146627.2018.1445974 [ Links ]

Hatherley, R.J., 2011, Mezirow's transformative learning theory, viewed 23 August 2017, from http://mdde.wikispaces.com/file/view/Mezirow%E2%80%99s%20Transformative%20Learning %20Theory,%20MDDE612,%20Assignment%232,%20%20Review%20%231.pdf/430268922/.

Kirsten, A.M., 2017, Early childhood development provision in rural and urban contexts in the North-West province, Potchefstroom Campus, North-West University, Potchefstroom.

Kortjass, M., 2019, 'Reflective self-study for an integrated learning approach to early childhood mathematics teacher education', South African Journal of Childhood Education 9(1), a576. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v9i1.576 [ Links ]

Leggett, N. & Ford, M., 2016, 'Group time experiences: Belonging, being and becoming through active participation within early childhood communities', Early Childhood Education Journal 44, 191-200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-015-0702-9 [ Links ]

Maluleke, N.P., Khoza-Shangase, K. & Kanji, A., 2019, 'Communication and school readiness abilities of children with hearing impairment in South Africa: A retrospective review of early intervention preschool records', South African Journal of Communication Disorders 66(1), a604. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajcd.v66i1.604 [ Links ]

Meier, C. & Marais, P., 2018, Management in early childhood education. A South African perspective, 3rd edn., Van Schaik Publishers, Pretoria.

Mezirow, J., 1991, Transformative dimensions of adult learning Jossey-Bass Co, San Francisco, CA.

Mezirow, J., 1997, 'Transformative learning: Theory to practice', New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 74, 5-12. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.7401 [ Links ]

Mezirow, J., 2000, 'Learning to think like an adult: Core concepts of transformational learning', in J. Mezirow and Associates (eds.), Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in progress, pp. 3-34, Jossey-Bass Co, San Francisco, CA.

Moodley, G., 2013, Implementation of the curriculum and assessment policy statements: Challenges and implications for teaching and learning, University of South Africa.

Murris, K., 2019, 'Children's development, capability approaches and post developmental child: The birth to four curriculum in South Africa', Global Studies of Childhood 9(1), 56-71. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043610619832894 [ Links ]

Ntumi, S., 2016, 'Challenges pre-school teachers face in the implementation of the early childhood curriculum in the Cape Coast Metropolis', Journal of Education and Practice 7(1), 54-66. [ Links ]

Reetu, C., Renu, G. & Adarsh, S., 2017, 'Quality early childhood care and education in India: Initiatives, practice, challenges and enablers', Asia-Pacific Journal of Research. In Early Childhood Education 11(1), 41-67. https://doi.org/10.17206/apjrece.2017.11.1.41 [ Links ]

Rudolph, N., 2017, 'Hierarchies of knowledge, incommensurabilities and silences in South African ECD policy: Whose knowledge counts?', Journal of Pedagogy/Pedagogický Casopis 8(1), 77-98. https://doi.org/10.1515/jped-2017-0004 [ Links ]

Ritz, A., 2010, 'International students and transformative learning in a multicultural formal educational context', Educational Forum 74(2), 158-166. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131721003608497 [ Links ]

Samaras, A., 2011, Self-study teacher research: Improving your practice through collaborative inquiry, Sage, London.

Somantri, A.S., Sulaeman, M., Ghoer, F.R., Firmansyah, Y. & Noviantoro, N., 2019, Integrating character-based thematic learning activities to promote early child' character acquisition, Universitas Islam Nusantara, Indonesia.

Soni, R., 2015, Theme based early childhood care and education programme: A Resource Book, National Council of Educational Research and Training, New Delhi.

South African Early Childhood Review, 2019, Ilifa Labantwana, Department of Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation in the Presidency, Cape Town.

Steyn, G.M., 2017, 'Transformative learning through teacher collaboration: A case study', Koers - Bulletin for Christian Scholarship 82(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.19108/KOERS.82.1.2220 [ Links ]

Taylor, E.W. & Cranton, P., 2013, 'A theory in progress? Issues in transformative learning theory', European Journal for Research on the Education and Learning of Adults 4(1), 33-47. https://doi.org/10.3384/rela.2000-7426.rela5000 [ Links ]

UNESCO International Bureau of Education, 2017, Training tools for curriculum development: Developing and implementing curriculum frameworks, UNESCO International Bureau of Education, Paris.

Van der Walt, J.P., Swart, I. & De Beer, S., 2014, 'Informal community-based early childhood development as a focus for urban public theology in South Africa', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 70(3), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v70i3.2769 [ Links ]

Varun, A. & Venugopal, K., 2016, 'Impact of thematic approach on communication skills in preschool', Imperial Journal of Interdisciplinary Research (IJIR) 2(10), 394-397, ISSN: 2454-1362, viewed from http://www.onlinejournal.in. [ Links ]

Vorster, A., Sacks, A., Amod, Z., Seabi, J. & Kern, A., 2016, 'The everyday experiences of early childhood caregivers: Challenges in an under-resourced community', South African Journal of Childhood Education 6(1), 9 pages. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v6i1.257 [ Links ]

Yin, R.K., 2009, Case study research: Design and methods, 4th edn., Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Zin, D.M.M., Mohamed, S., Bakar, K.A. & Ismail, N.K., 2019, 'Further study on implementing thematic teaching in preschool: A needs analysis research', Creative Education 10, 2887-2898. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2019.1012214 [ Links ]

Zosh, J.M., Hopkins, E.J., Jensen, H., Liu, C., Neale, D., Hirsh-Pasek, K., et al., 2017, Learning through play: A review of the evidence, The LEGO Foundation, United Kingdom.

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Cynthia Zama

ZamaZ@ukzn.ac.za

Received: 25 Aug. 2021

Accepted: 11 May 2022

Published: 26 Sept. 2022