Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Childhood Education

versión On-line ISSN 2223-7682

versión impresa ISSN 2223-7674

SAJCE vol.12 no.1 Johannesburg 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v12i1.1170

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

How educators commit to enhancing children's participation in early childhood education pedagogical plans

Johanna HeikkaI; Titta KettukangasI; Leena TurjaII; Nina HeiskanenI

ISchool of Applied Educational Science and Teacher Education, Faculty of Philosophical, University of Eastern Finland, Joensuu, Finland

IIDepartment of Education, Faculty of Early Childhood Education, University of Jyväskylä, Jyväskylä, Finland

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: This is a descriptive study of children's participation plans in early childhood education (ECE) settings in Finland. The study adopted a multidimensional approach to find out how practices of children's participation were conceived in pedagogical plans made by ECE staff, representing a focus that is rare in the existing body of research

AIM: Aim of the study was to investigate educators' commitments to enhancing children's participation in pedagogical practices in their ECE settings

SETTING: Ten centre-based plans for children's participation composed by ECE staff at ECE centres were selected for the document data in this study

METHODS: This study employs the categorisation of the prerequisites and dimensions of children's participation in deductive qualitative content analysis (Turja 2017

RESULTS: Results of the analysis concludes that in early childhood education plans, there were comprehensive notions of prerequisites for participation. However, the study indicates that the level of participation varied between plans for different activities; it was highest in play and limited in terms of time and effect in other pedagogical and caregiving activities

CONCLUSION: Understanding the prerequisites and dimensions of children's participation is fundamental for planning and enacting participative pedagogy in child groups at ECE centres. In conclusion, this study suggests how to support ECE staff in interpreting and implementing children's participation in early childhood education

Keywords: children's participation; early childhood education; educators; pedagogical plans; pedagogy; participation practices; prerequisites for participation.

Introduction

Children's participation is seen as being based on the Convention on the Rights of the Child, UNCRC (United Nations 1989), which reflects particular core values of participation such as self-determination and democracy (Bae 2009; CoE 2012). The execution of children's participation is a time-consuming process that demands changes in legislation, policy and practice (Lansdown 2010), the implementation of which is where northern European countries are regarded as pioneers of early childhood education (ECE) (Theobold 2019).

The aim of this study is to investigate educators' professional commitment to implementing and enhancing young children's participation in ECE settings. The basis of pedagogical practices can be ascertained by examining curriculum texts, values (Einardottir et al. 2015) and concepts (Kettukangas 2017). Salminen and Poikonen (2017) reminded that a centre-based plan is a tool that allows the goals of the national curriculum come to life. According to Salminen and Annevirta (2016), participating in a shared curriculum process affects teachers' pedagogical thinking when planning the actual pedagogical practices. In 2017, we collected plans regarding children's participation, formulated reflectively by the staff in Finnish ECE centres to develop their pedagogical practices according to the new legislation and regulations. In Finland, ECE experienced a reform as day-care moved from the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health to the Ministry of Education and Culture in 2013 and again in 2015, with the completion of the Act on Early Childhood Education and Care (580/2015). With this legislation, day-care as a system transformed into goal-oriented early childhood education and care that emphasises pedagogy (540/2018 § 1). Firstly, the Finnish National Agency for Education produced a mandatory National Core Curriculum for ECEC (EDUFI 2016) based on the Act on Early Childhood Education and Care (see 540/2018 § 9). Before this norm, the core curriculum for early childhood education and care (ECEC) was only advisory. Secondly, mandatory local curricula were drawn up according to the National Core Curriculum for ECEC and introduced in 2017. Local curricula may be formulated as a common plan for local ECEC services or for different forms of local ECEC services separately (EDUFI 2016:9). These local plans could be either regional, municipality-specific or centre-based. Further, the personnel of ECEC centres can concretise the contents of these pedagogical documents at the level of a voluntary plan for their own child group, but all levels of pedagogical plans must comply with legislation and regulation (see 540/2018 § 22). However, the child's individual ECEC plan is always compulsory (540/2018 § 23).

One essential change in addition to strengthening the quality of pedagogy in ECEC in general was that the participation of children and their guardians in pedagogical planning, implementation and evaluation was included as obligatory for the first time in the contemporary Act on Early Childhood Education and Care (540/2018) in 2015 and further in the core curricula for preprimary education (EDUFI 2014, 2016), as well as for early childhood education and care (EDUFI 2018). Early childhood education and care are needed now to develop policies and structures to support participation in various ways (EDUFI 2016:24, 30).

Children's participation principles are generally expressed in these steering regulations, arousing the need for support amongst ECE professionals to concretise them into practice (Sevón et al. 2021). As the content of the curriculum (2016) changed and was implemented into practice, participation became more explicit in research and early childhood discourses, as well as in practical development and local alignments. Although some of the centres have already developed various strategies for enabling children's and their parents' participation through training and projects (e.g. Venninen & Leinonen 2013), clear nation-wide strategies and practices are missing (Kangas 2016; Virkki 2015).

This study was approached with the understanding that children's participation is a multifaceted, complex and dynamic phenomenon (Woodhead 2010) that can be studied in several contexts, on multiple levels from societal to personal and with varying theoretical linkages (Malone & Hartung 2010; Sinclair 2004). Within this study's data limits, participation was investigated mainly as an institutional and interactional level phenomenon.

The commitments in the Finnish curricula concerning learning and learners correspond to the sociocultural paradigm (Rogoff 2003; Vygotsky 1978) that emphasises humans as active agents who learn and develop holistically and dialogically in cultural contexts and interpersonal relationships, as well as the new sociology of childhood paradigm (James, Jenks & Prout 1998) that supports the views of childhood with its own justification and children as social actors with their own interests and competence, who both influence their world and are influenced by surrounding structures and relationships. These paradigms form the basis of this study, combined with the child's rights paradigm, especially concerning UNCRC Articles 2, 3, 5, 12, 13, and 17. They outline everyone's equal right to be informed and listened to, to have one's opinions taken into account and to express oneself freely, with respect to young children's needs for protection as well as guidance and support in the exercise of their rights and with primary consideration of the best interests of the child (CoE 2012; Lansdown 2010).

Concerning the data, the researchers understand the cooperatively formulated pedagogical plans of the centre staff as joint commitments to act in a certain way based on Shier's (2001) conceptualising of the phases of educators' readiness to help progress children's participation in pedagogical plans. According to him, in the stage of 'opening', individual educators are personally ready to think and act in a certain new way. Secondly, the organisation must create an 'opportunity' to operate according to this personal readiness by providing needed resources, knowledge, skills and approaches. Finally, the organisation establishes an 'obligation' along which the new operation method becomes the jointly agreed policy.

Studying the content of these plans provided a multidimensional picture of children's and guardians' participation, concretised in operations of ECE practice. The data are derived uniquely from the coworking organisations at the time when the new national regulations have urged service providers to develop their programmes towards children's participation. The results will guide the next steps taken in ECE policy, professional development and related research.

Participation as a concept

The actualisation of children's participation in ECE settings is challenged by the many alternative ways to conceptualise young children's participation (Theobald 2019). Based on the UNCRC, it is generally formulated as a child's right to express his or her views freely in all matters affecting the child and to have them taken into account 'in accordance with the age and maturity of the child' (Article 12). This kind of conditional formulation, also found in the Finnish Act on ECEC (540/2018), allows space for varying and tensional interpretations amongst service providers and educators (e.g. Lundy 2007). When looking at them from different perspectives, the interpretations may focus narrowly on individuals or more widely also on their communities and contexts (Thomas & Percy-Smith 2010).

Firstly, whilst young children are regarded as capable to participate in many ways - for example, by making choices and communicating in numerous ways, even before gaining spoken language (Nyland 2009) - their evolving competence may be seen only as a personal psychological property that is developed through learning and maturation (CoE 2012). Instead, a wider relational approach takes into account the expectations, support and restrictions of the environment, pinpointing the fact that children's capacities are situated and negotiated in everyday praxis (Oswell 2013:188).

Secondly, participation can be seen as an individual right or as a shared one. The individualistic perspective focuses on personal well-being, autonomy and self-realisation through expressing one's own views and making individual choices (Bae 2009). Increasingly, however, the focus is moved to collective and relational aspects of participation (Horgan et al. 2017), such as learning about exercising democracy, influencing practices and environments, children and families' participation in service development, delivery and evaluation and opportunities for dialogue and information-sharing with mutual respect and cooperation amongst participants (CoE 2012). The wider approach aims to reconcile both individual and collective aspects in a way that does not harm the child or others (cf. Alderson 2008).

Thirdly, individuality refers to educators' personal views on children's capacities and interests and individuals' power to decide to what extent each child is informed, listened to and involved in decision-making. In turn, the wider, contextual approach elaborates on the status of children so that educators need to provide children with opportunities and support to exercise their rights and evolving capacities by sharing power and involving them in negotiations and decision-making (UNCRC Article 5; Lansdown 2010). This kind of empowerment of children leans on the commitment of entire educator teams to enhance this objective with shared practices (e.g. Shier 2001).

The well-known participation models of Hart (1992) and Shier (2001) describe personnel's stepwise proceeding of children's empowerment in decision-making through ladders or pathways. Shier (2010, 2019), however, has later regarded these one-dimensional models as inadequate to catch the multidimensional and relational participation processes. Further, some criticism (Kirby et al. 2003; Malone & Hartung 2010; Sinclair 2004) is targeted towards their hierarchy that may lead to achieving only the top level as the main objective, although different levels of empowerment are appropriate in different situations.

Finally, children's participation practices are critiqued for being based too much on separate, formal techniques and choice routines about matters determined by educators instead of children's unique forms of participation in all interactions and interests embedded in their daily life (Bae 2009; Lundy 2007). Within a holistic approach, children are regarded to experience their participation as meaningful through everyday practices of playing, caring and 'doing' education (Horgan et al. 2017; Nyland 2009). Actually, this leads to a participatory pedagogy (Kangas 2016).

We approach the concept of children's participation widely and holistically as described above and by taking multiple factors and dimensions into account in this study. In the analysis, we have applied Turja's (2017; 2018) a multidimensional conceptual model of children's participation, which is described next. It is constructed abductively, based on both earlier research and conceptual models of participation, as well as the data of narratives on children's participation collected from Finnish ECE educators in several refresher courses during 2006-2016. The tentative model variations have been reflected within the courses in the long run.

The multidimensional model of participation

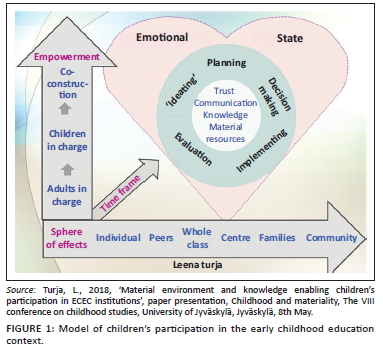

The model (Turja 2017) strives to organise multiple adequate dimensions and aspects into one conceptual framework that is simple enough for ECE practitioners to manage as a tool to reflect on and develop their practices. It consists of prerequisites enabling children's participation, dimensions of participation and the process viewpoint to involvement (Figure 1) - all explained in the following.

The four intertwined prerequisites refer to children's evolving but situated competence (UNCRC Article 5), the most fundamental of which is the atmosphere of trust (Alderson 2008; Lundy 2007; Owens 2005; Shier 2010). To start an interaction and cooperation with companions, all the participants need to feel safety, self-confidence and mutual trust. Educators need these for sharing power with children. Communication is key to successful participation: children need opportunities to communicate with adequate means in order to make themselves understood and to understand others and the information shared with them (Clark 2005; Lundy 2007; UNCRC Articles 5, 13). Furthermore, educators and children need to co-create knowledge concerning all matters essential for the children to enable their meaningful initiations and participation (Bae 2009; Hart 1992; UNCRC Article 17). Lastly, access to all essential materials, places and other resources is important for children's agency, especially concerning the youngest children, who ideate and start activities and make choices guided by their immediate physical environment (Owens 2005). Educators are responsible for promoting these prerequisites.

The three dimensions of participation unify several dimensions presented by Kirby and others (2003). Children's empowerment (Hart 1992; Shier 2001) focuses on the power relations between child and educator in pedagogical activities. This dimension is simplified according to Lansdown (2010:20) into three categories, with a notice that each of them may be appropriate depending on the context and the phase of activity:

-

Adult-led position where children are heard, consulted, asking permissions and making restricted choices

-

Child-led position where adults watch over or assist children with their ideas

-

Equal position between adults and children with joint negotiations, decisions and collaboration.

The sphere of effects corresponds with Kirby and others' dimensions of 'focus' and 'content' of decision-making. It describes how widely influential and recognisable the child's or children's participation is. The continuum extends from personal matters towards those shared with peers, the whole group, the centre, families and even the wider community. Time frame takes into account the duration of an activity and its effects (Kirby et al. 2003: 'frequency and duration of participation'). Some activities, such as co-constructing rules for a group, may take a relatively short time but have lasting effects throughout the whole year. Deciding on free-play activities represents the short-term 'on-off' participation, whereas cooperative project works belong to long-term practices.

Children and their guardians should be involved in every step of the pedagogical process including planning, implementation and evaluation (Act on ECEC 540/2018). Each phase involves decision-making (Lansdown 2010). Finally, a successful participation process has various impacts on children's lives, benefitting both individuals and the community (Lansdown 2010). The immediate impact is a positive emotional state, referring to a sense of belonging (Rinaldi 2005), increasing self-esteem, empathy and responsibility (Shier 2001), as well as experiences of solidarity, unity and fellowship (Sandberg and Eriksson 2010); therefore, it further strengthens the 'atmosphere of trust'.

Children's participation in the practices of early childhood education settings

Correia et al. (2019) completed a systematic review of 36 publications of empirical research on children's participation in ECE settings published during 2001-2017. Majority of the studies were qualitative studies conducted in northern European countries, investigating ideas of participation and focusing on the educators' viewpoint. Interestingly, no one analysed the curricula or pedagogical plans of ECE centres. A third of the studies focused on practices related to participation - those being relevant to this study's interests. Only a few of the reviewed studies reported positive child outcomes of participation in self-regulation, autonomy, communication and problem-solving skills.

Venninen and Leinonen (2013) studied the effects of long-term training on practices of 82 teams in 21 Finnish ECE centres, pinpointing the necessity of reflection, evaluation and continuous transformation for acquiring new practices. The teams' self-reports revealed development in delving into children's perspectives, being present for children, supporting them in self-expression and with their own ideas, emphasising play and spontaneous activities and especially in giving room to their choices. They had learned to include children's viewpoints better in their own planning and to make spontaneous adaptations to ongoing pedagogic activities according to children's suggestions. Instead, shared decision-making as well as designing activities and physical environments together with children were slightly developed but implemented quite rarely.

As above, some other studies (Bae 2009; Einarsdottir 2005; Ivrendi 2017; Rosen 2010) also considered play to be remarkable for children's involvement, learning, self-determination, individual and joint choices and open-ended activities. However, children's limited opportunities to influence playtimes, materials and environments, as well as educators' withdrawal from play interaction are seen as drawbacks for participation (Brotherus & Kangas 2018). Actually, Roos (2015) concluded, based on her research in child groups, that children are living in two cultures: their own peer culture (e.g. play) and the adults' organised one.

According to some studies (Almqvist & Almqvist 2015; Kangas 2016; Leinonen & Venninen 2012), apart from play, educators tend to give children only restricted opportunities to make choices and take initiative within the preplanned frames. Evidence from earlier studies (Bae 2010; Nyland 2009; Roos 2015; Virkki 2015) shows that this also concerns caregiving activities (e.g. mealtimes, nap, dressing, toileting) that are often implemented only according to unconscious rules and habits (Kettukangas 2017).

Further, children may be listened to, but it is up to the adults how their views are finally taken into account in decision-making (Lundy 2007). Alasuutari (2014) studied teacher-parent meetings concerning the child's individual education plan with the result that, mostly, children's opinions gathered beforehand were not seriously valued or included in the plans. Children as active agents, however, can use many strategies to exercise their rights and to accommodate and resist educators' orders in daily interactions and negotiations (Markström & Halldén 2009; Sairanen, Kumpulainen & Kajamaa 2020).

Children's empowerment is successfully enhanced by many strategies. Weckström and others (2021) reported how a narrative 'storycrafting' method was used to enable children's agency within long-term projects based on their stories. Clement (2019) described children's own agency in building their classroom environment. According to Knauf (2019), such features of the physical environment as open views, flexible usage, accessibility and multifunctionality of material and representations of children facilitated children's self-determined activities.

Many studies (Bae 2009; Emilson & Folkesson 2006; Kangas 2016; Mesquita-Pires 2012; Sairanen et al. 2020; Salminen 2013; Sandberg & Erikson 2010) have indicated that respectful and reciprocal adult-child interaction as the core of participation practices is connected to educators' acceptive and less controlling role, jointly negotiated rules and constructive group management skills, as well as child-friendly nonverbal and verbal communication styles, responsivity and pedagogical sensitivity.

The recognised facilitators and restrictors of children's participation are the opposite sides of the same coin. Attitudinal factors are linked to educators' image of the child and understandings of participation (Bae 2010; Kangas 2016; Sandberg & Erikson 2010), causing, for example, the underestimation of children's competence and worries about undermined pedagogical authority (Lundy 2007). Factors linked to professional development concern pedagogical roles (Bae 2009; Salminen 2013), skills and knowledge in involving children and supporting their participation at different ages and with diverse backgrounds or disabilities (Almqvist & Almqvist 2015; Emilson & Folkesson 2006; Franklin 2013; Kangas 2016; Sairanen et. al.2020; Sévon et al. 2021) and teamwork enhancing reflection and shared understanding of participation practices (Mesquita-Pires 2012; Venninen & Leinonen 2013). Structural and environmental factors consist of built environments, staff resources and grouping of children, as well as cultural ways to organise pedagogical activities, schedules, routines and material environments (Kangas 2016; Knauf 2019; Mesquita-Pires 2012; Sandberg & Erikson 2010; Virkki 2015).

To conclude, supporting children's competence and autonomy and acknowledging their 'voices' within adult-led activities seem to be less challenging to embrace than activities based on adult-child collaboration and power balancing, although successful strategies are established as well. Furthermore, the ideas of participation may vary greatly, leading to diverse focuses in practices and research (e.g. Correia et al. 2019). This study has adopted a wide, holistic and multidimensional approach to find out how practices of children's participation are used in pedagogical plans made by ECE staff, representing a focus that is rare in the existing body of research.

Study objectives and methods

The aim of this study was to investigate educators' commitment to implementing children's participation in pedagogical practices in their ECE settings, as written in the pedagogical plans formulated by the staff of 10 ECE centres in Finland. Statements in these plans concerned objectives, principles and concrete work methods. Informed by the multidimensional participation model as the basis of analysis, the research task was defined with the following research questions:

-

What kinds of prerequisites for children's participation are ECE educators committed to in order to enhance their practice, according to statements included in the pedagogical plans?

-

How is the enactment of dimensions of children's participation conceived by the ECE professionals in accordance with the statements included in the pedagogical plans?

Research data

The data were collected during the year 2017. Ten centre-based plans for children's participation in ECE were selected for the document data in this study. The plans for children's participation were documents composed by ECE staff at ECE centres in one municipality in Finland. The composition of centre-based plans is not obligatory in Finland. The ECE leader of the municipality initiated the planning process as part of the local ECE curriculum implementation project. Children's participation in ECE was emphasised as a development goal in the local curriculum of the municipality. To ensure the implementation of children's participation as required by the National Core Curriculum for Early Childhood Education and Care (EDUFI 2018) and the local ECE curriculum, the ECE leader instructed each ECE centre to draft a plan for how children's participation would be implemented in the daily pedagogical activities (e.g. basic and pedagogical activities and play) of all child groups in the centre. The ECE centre directors led the composition of concrete action plans, with which the staff aimed to enact the goals of children's participation during the next year. This was based on a shared discussion and agreements amongst the whole staff about the practices and how to enact them in the daily pedagogy. Plans were made to guide practices of all educators in the centre for the whole year. This process did not include guidance from outside the centre. The ECE centres were located in a medium-sized municipality in Finland. All centres in the municipality participated in the study. The centres consisted of 1‒10 child groups with 12‒24 children in each group. The staff at each centre consisted of 3‒31 persons, and the total number of ECE teachers participating in the study was 43. Along with the ECE teachers, there were ECE professionals, such as child carers, working in the centres. The total number of ECE staff participating in drafting plans was approximately 150, of which nearly 35% were ECE teachers and 47% were child carers. The plans differed slightly in length and content. One plan was approximately 1‒10 pages. Most of the plans were three to six pages long. One of the plans was one page long, and one plan was two pages long. One of the plans was eight pages long, and one plan was 10 pages long. Most of the plans included subheadings such as 'adult-child interaction', 'taking care of the well-being of children in basic activities' and 'children's participation in play'. However, subheadings varied between plans, and some of the plans did not include subheadings (e.g. the shortest plan). Some of the plans were written very concisely and others were written in more detail.

Data analysis

Coffey (2014) characterised documents as artefacts produced in a study setting for certain purposes. A document is a social contract and reflects how the authors perceive social reality. This starting point provides the purpose of analysis and directs the methodological choices of the research. The methods of the document analysis are chosen so that the meaning-making of the authors on the analysed documents can be revealed.

Enquiry into the substantive content of the plans for children's participation in ECE was performed through the application of deductive qualitative analysis (Patton 2015). Qualitative content analysis was used to organise, condense and categorise the document data to investigate ECE professionals' perceptions of the prerequisites and dimensions of children's participation in ECE. The data analysis process followed the conceptual framework of children's participation developed by Turja (2017). This approach led to the categorisation of the data according to the concepts derived from Turja's conceptualisation of children's participation. The fundamental prerequisites for children's participation were ways of communication, atmosphere of trust and access to knowledge and material resources. The dimensions of participation were empowerment, sphere of effects and time frame.

To start, it was important to compare the analyses of one document (10% of the data) done by three researchers and confirm that the categories were being coded in a similar way to ensure the reliability of the findings (cf. Krippendorff 2013). The first step in the actual data analysis process was to identify the expressions connected to the key concepts selected for the study, which were the three dimensions of children's participation presented in the model. The unit of analysis was the part of the text that had a factual connection with the concepts that were important for the study. For example, a bit of text about providing positive feedback for children formulated a unit connected with the subcategory of children's self-confidence in the analysis. This first phase of the analysis resulted in the identification of the main categories in the data. After the main categories were identified, based on the theoretical concepts, the content of the categories was reduced and clustered to form subcategories. After this phase, the researchers organised the subcategories under the main ones to form a comprehensive picture of the categories and their content, as well as their hierarchical relationships within the whole data set. To support the credibility of the study, some excerpts from the data are included in this article.

Findings

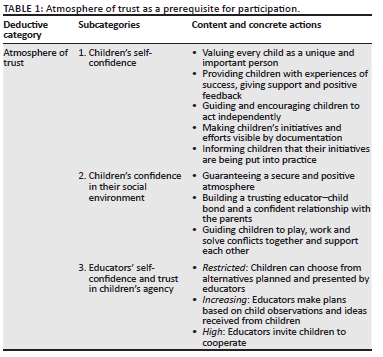

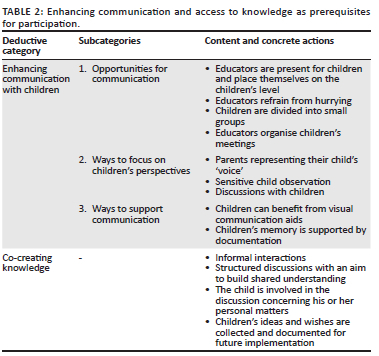

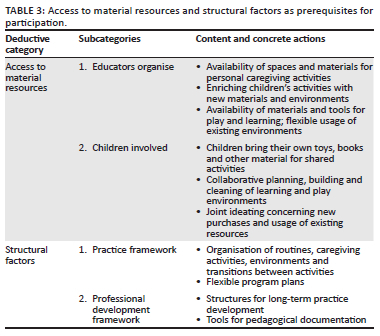

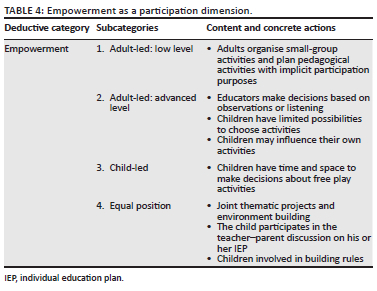

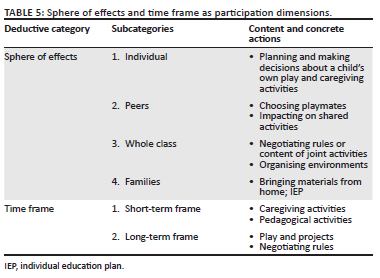

The findings and the related categories of the prerequisites and dimensions of children's participation in ECE plans are presented here. The descriptive contents of the main categories are presented in Tables 1-5.

Prerequisites for children's participation in early childhood education plans

The prerequisites for children's participation consist of four deductively formed main categories: atmosphere of trust, enhancing communication with children, co-creating knowledge of daily life and access to material resources. The prerequisites of participation are intertwined, and the dimensions form a three-dimensional space for participation activities, and one activity can hence be included in different categories. In addition, this study identified structural factors to be added into these main categories. All the categories with descriptive contents are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

The first main category, atmosphere of trust, consists of three subcategories (see Table 1). Several statements, in general, aimed to strengthen children's positive self-image and self-confidence as categorised in the 'children's self-confidence' subcategory. Treating children as unique, important persons is seen in the following example: the educator must in a positive atmosphere 'encourage everybody to play in their own way' (Plan 6). Further, expressions about providing children with experiences with success, self-guided activities and feedback that indicates the worth of their ideas and initiatives were included here. Statements like '[a] child is aware of when his or her wish has come true' (Plan 5) were visible in several plans.

Expressions in the 'confidence in their social environment' sub-category dealt firstly with the general atmosphere and social relationships. For example, educators should enhance 'positive pedagogy and attitudes towards one another, noticing each other's strengths' (Plan 6). Many statements concerned positive communication amongst participants, educators' availability for children, stability and predictability with routines and rules, forbidding bullying, having fun together and holding children. Secondly, according to the statements, educators must build a trusting educator-child bond by being sensitive and responding to individual needs, emotions and personal traits that are also supported by a confidential relationship with the child's guardians. Thirdly, mutual confidence in the group can be enhanced by guiding every child to play and work with the other children, support each other and solve conflicts together.

The 'educators' self-confidence and trust in children's agency' subcategory was only implicitly recognisable in the statements that dealt with educators' child view and readiness to involve children in pedagogical processes. Actually, these statements belong primarily to the children's empowerment dimension described in detail in that part of the results. Therefore, the following classification is only tentative. Firstly, educators with only restricted readiness allow children to choose from alternatives that are preplanned and presented by educators. Secondly, those with increasing readiness make plans based on their own observations of children and ideas received from them. Thirdly, educators with a high readiness build thematic activities and projects together with children based on the children's ideas. What is remarkable is whether educators regard themselves as enablers of children's present agency or whether they wait for the children to learn and grow older: 'When the play becomes more self-directed, the educator trusts children and she doesn't have to be involved all the time. The educator gives space for children-initiated play' (Plan 8).

Statements belonging to the second main category, enhancing communication with children, were classified into three subcategories (see Table 2). 'Opportunities for communication' included statements describing multiple ways to create proximity, time and space for informal communication. In addition, organising children's meetings for discussion was mentioned several times. 'Ways to focus on children's perspectives' consisted of statements involving parents as transmitters of their child's voice as well as using sensitive child observation and discussions to listen to children's views: 'Educators listen to children respectfully and strive to reach the child's interpretation of the situation' (Plan 8). The subcategory 'ways to support communication' concerns statements referring to visual communication such as drawings, pictures and photographs as a means of communication. Documentation to visualise discussed issues such as children's wishes for activities was mentioned in some plans, including 'a tree with wish-leaves' on the wall and 'a blog of the child group'.

Expressions belonging to the third main category, co-creating knowledge (Table 2), are related to actions aiming to understand each other's thoughts and co-create shared understanding about various daily life issues in order to contribute to them meaningfully. Knowledge co-creation was mentioned to happen in informal interactions (Plan 1: educators shall 'model young children's play; discuss more with children'), in joint pedagogical discussions (circle times, weekly planning meetings) and, for example, by involving the child in parent-educator discussions about the child's individual education plan (IEP). Discussing the group rules or building them together was seldom mentioned. More common were statements about collecting children's ideas and wishes to inform future planning: 'We write and visualise children's wishes on the wall' (Plan 6).

The fourth main category, access to material resources, was divided into two subcategories depending on children's influence on material resources (see Table 3). The statements of the first subcategory focused on how educators organise equipment, materials and environments, including the habits of their use, so that they meet individual caregiving needs (access to toilet or resting place), enrich play and exploring and are available to children without restrictions. For example, 'a child's young age does not restrict him/her to play in various group environments' and 'older children are encouraged to independently get the materials they need' (Plan 1). Statements classified into the second category concerned practices that strengthen children's involvement in organising material resources: 'Children plan and build play areas together with educators. For example, children bring "merchandise" from home for market-play' (Plan 7), and they may take care of environments. Some statements valued children's expertise in ideating material resources: 'Children are involved in mapping out needed materials' (Plan 6).

The new main category, structural factors (Table 3), was divided into two subcategories (see Table 3). The statements referring to practice framework of ECE institutions concerned various routines (e.g. cleaning and daily schedules), caregiving activities, gradual and smooth transitions from one activity to another and flexible usage and transformability of indoor environments. These were mentioned almost in every plan. Critical assessment of conventional habits was recommended to remove unnecessary barriers to implementing children's ideas and participation. Flexible monthly and weekly programme plans that 'allow space for changes and children's wishes and needs' (Plan 6) were also often mentioned. Statements referring to professional development framework concerned jointly negotiated values and principles, as well as strategies and tools for the long-term development of educators' own work based on evaluation and feedback from parents and children. Furthermore, tools for pedagogical documentation (e.g. child-group plans and agreements, individual plans and portfolios) were seen as key to developing ECE practices towards children's participation.

The dimensions of children's participation in early childhood education plans

The three dimensions of children's participation, namely empowerment, the sphere of effects and time frame, were present in the plans representing educators' commitment to the pursuit of children's participation (Tables 4 and 5).

In the dimension of empowerment (Table 4), the adult-child power balance is central. In the plans, empowerment was described as an extension of a child's competence to make decisions. The child's capacity for participation was seen to expand with age and development. Instead of the original three subcategories, we formed four subcategories. The first one, adult-led on low level, included statements showing that decisions are made purely by adults in order to enhance children's participation somehow. An example of this is to 'divide children into small groups', but without an explicit explanation for that. Supposedly, the idea was to ease interaction and listening to children in small groups.

The second subcategory, adult-led on advanced level, concerned such statements where adults are in charge and their decisions are based on the information they hold about the children. Several of them referred to adults making decisions and planning based on their observations of children or listening to them. The statements expressed that adults notice children's ideas and initiatives in planning. More than half of the expressions included in this category concerned children's right to make choices; they may choose their play or activities from a given selection, which is sometimes limited. Some statements indicated restrictions concerning the right to choose, choosing only 'every now and then' (Plan 6), choosing materials for handicrafts and choosing a song to sing and play in a music session. Within caregiving activities (mealtimes, toilet, nap, dressing), children were allowed to choose whether they wanted to quit playing and go dress in order to transition outdoors earlier and when to go to the toilet. Mealtime choices concerned the portion size and content of meals and whether to use a spoon or a fork. Some participation plans included mentions that children are allowed to make choices about naptime. Some statements made reservations for adults' consideration, as described in Plan 5: 'A child may influence their clothing' and 'children may influence their bed's placement'.

The third subcategory, child-led, consists of statements that put children in charge. These expressions concerned mainly play, more specifically free play, where children were given time and space for self-directed activities and opportunities to choose what and with whom they wanted to play, but usually the effect of the sphere was individual. Children's cooperation was mentioned quite rarely in the plans. It concerned negotiation and solving contradictions and influencing the day's story by voting.

The fourth subcategory, equal position, included some statements describing the collaboration between educators and children. Planning and implementing themes and projects were mentioned to happen in cooperation and it was stated that planning is done together with children and educators in small groups. Cooperative environmental planning and construction were also mentioned. Statements did not explain in detail the planning practices, although noticing, discussion, negotiation and responding to children's interests were mentioned in almost every plan: 'We shall live in the moment, observe, sense and listen to the child, seize the wishes and thoughts of the children' (Plan 5). One plan described a children's meeting that implements both planning and assessment. One statement concerned the joint planning of rules for outdoor safety. Only a few plans included mentions of children's involvement in teacher-parent discussions on the child's IEP, although it is obligatory for everyone to make the IEP by listening to the child.

Statements on the dimension of sphere of effects (Table 5) focused mainly on individual issues concerning children's opportunities to plan and make decisions about their own play and caregiving activities. The sphere of effects extended to 'peers' and included statements about choosing playmates or impacting on shared activities in a small group. The sphere of effects was classified to extend to concern the whole class or even the entire centre when expressions of cooperation targeted organising activities or play environments for everyone in the group or negotiating the rules. In the plans, the sphere of effects hardly extended to concerned families except for a few expressions, noting that children could bring some materials from home and contribute to IEP discussions. None of the participation plans included expressions about the sphere of effects on the community level.

The main category of the time frame of participation (Table 5) refers both to the duration of an activity or project and to the duration of its effects. Analysis of the participation plans showed that expressions referring to long-term frame duration or effects focused mostly on play, and short-term frame participation concerned mostly caregiving activities but also play. Many short-duration activities are individual in their effects. Regularly repeated short-term participation practices (circle times, music sessions), however, can be classified as belonging to the long-term frame. Children's age, development and experience were factors to be considered: the younger the children, the shorter the duration of their action.

Regarding the short-term frame participation, expressions of caregiving activities concerned children's opportunities to choose their place during mealtimes and educators' trust on children's estimations of portion sizes. Children may also influence their personal clothing and toilet times. Statements of play noted that children may choose their play and their playmates. A few short-term frame participation expressions concerned pedagogical activity sessions such as music sessions where children can choose the songs within educators' pre-planned frames.

The duration of long-term frame play, as the most often mentioned activity, was extended by allowing children to leave the materials in their spots for the next playtime. Another main issue was involving children in designing and constructing play environments. This kind of planning is effective for a single day or for weeks, sometimes even permanently. Only one plan described caregiving activities with long-lasting effects concerning children's right to choose their own bed and to bring a naptime toy (sleeping buddy) from home. Another plan described a safety area the children planned for themselves to stay in whilst waiting for educators before transitioning to outdoor play. This kind of activity, including negotiation of rules, represents a long-duration effect and simultaneously also concerns the whole group.

Children's participation in the different phases of the pedagogical process has been noted in the pedagogical plans. Most statements mentioned children's participation in planning pedagogical activities and constructing a learning and play environment. Children's participation in enacting and evaluating pedagogical activities was mentioned more rarely. The plans mentioning evaluation, however, did not describe how it was intended to be put into practice. The effects of practices were not expressed explicitly.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated plans on children's participation formulated reflectively by the staff in Finnish ECE centres. The findings revealed that children's participation is well rooted in educators' thinking. However, much remains to be learned in order to understand how participation can be enacted holistically in practice. In the first research question, we asked what kinds of prerequisites for children's participation are ECE educators committed to in order to enhance their practice, according to statements included in the pedagogical plans? The data were rich in terms of prerequisites of participation, especially regarding the atmosphere of trust and enhancing communication. However, the intended activities did not optimally support the conditions for the child's participation. Children's participation was perceived in the plans mainly in relation to listening to and documenting children's wishes about pedagogical activities and providing possibilities for them to influence and make choices within activities.

Institutional structures may challenge or benefit the implementation and development of pedagogy of participation (e.g. Salminen 2013). In this study, the structural prerequisites of children's participation were identified as the organisation of the daily activities in the child groups, so that they enabled individual decision-making in terms of pace, caregiving and play. A pitfall in the educators' thinking was that participation was considered from the perspective of individual children, with less emphasis on community aspects. The holistic approach aims to reconcile both individual and collective aspects (cf. Alderson 2008; Horgan et al. 2017). According to Kangas (2016), children's participation should be regarded as opportunities for children to influence their peer group culture. The role of the educator is to act as an enabler of the children's influence.

The second research question asked was 'how is the enactment of dimensions of children's participation conceived by the ECE professionals in accordance with the statements included in the pedagogical plans?' Children's participation was highest in terms of time and the sphere of effects in play activities, whereas in other pedagogical activities, their level of participation was limited to making short-term choices, mainly about their own actions within activities planned by educators. Also, Kangas (2016) and Leinonen and Venninen (2014) showed that pedagogical activities are usually preplanned by educators. However, children's ideas regarding activities are taken into consideration. Children's participation practices are critiqued for being too much based on choice routines and formal techniques instead of children's holistic forms of participation regarding their daily interactions and actions (Bae 2009; Lundy 2007). The wider, contextual approach elaborates on the role of children so that they are provided with support to exercise their rights and evolving capacities by sharing power and involving them in negotiations and decision-making (UNCRC Article 5; Lansdown 2010). Instead of seeing participation as taking place within the limits and place allowed by adults, it should define all situations that are relevant to children (Horgan et al. 2017; Nyland 2009). This view corresponds with the National Core Curriculum for Early Childhood Education and Care (2018).

The significance of professional development emerged in the plans. The community perspective (Shier 2001) to participation in education requires commitment from all educators in the child groups to develop pedagogy by a conscious critical review of practices through the training and development of pedagogical thinking (Lim & Lim 2013). Professional development is needed to understand the multidimensionality of children's participation throughout the pedagogical process and to communicate it in the pedagogical plans. The previous studies (Kettukangas, Heikka & Pitkäniemi 2017) revealed that educators evaluate their practices as participative, but in-depth investigation indicates that educators' capabilities of making informed evaluations about their practices might be limited because of their narrow conceptualisation of children's participation. Woodhead (2010) noted that participation is ambiguous and complex in nature, and its realisation relies, first of all, on educators understanding this concept and their attitudinal readiness to share power. Holding onto the traditional professional role of the teacher with a power status over children limits children's empowerment (Bae 2010; Emilson & Folkesson 2006; Salminen 2013).

The realisation of children's participation in ECE practice is related to the limitations of this study, as the intention was to study only the plans, and when the effects on the implementation of the plans are manifold, this study cannot reach knowledge on how the participation will be realised in practice based on these plans. As this was not the aim of this study, it can only suggest how planning may function as one of the obstacles to achieving the potentials of participation-based pedagogy. However, teacher planning implements teachers' pedagogical thinking being 'a gate of consciousness' between a curriculum and teachers' actions, as Salminen and Annevirta (2016) described it. In addition, according to Shier (2001), the educators' readiness to enhance children's participation is connected to the obligation established by the organisation.

The plans analysed in this study represent a curriculum text being a consensus produced collegially by the educational community. The expression is concise but generous, which can undermine interpretation. The reliability of interpretation was sought to be strengthened by researcher triangulation, as interpretations were confirmed by the analysis of the three researchers. One of the benefits of the plans as research data was that the data produced new categories to the model of children's participation (Turja 2017).

Nordic countries have decisively embraced rights-based perspectives as core to the policy, curriculum and pedagogy of ECE programmes (Theobald 2019), which has also increased research on children's participation, especially in Sweden, Finland and Norway (Correia et al. 2019). Accordingly, the results of this study as well as the other related ones can benefit other countries in research, policy and practice. We have supposed that statements written in the studied pedagogical plans are joint commitments based on educators' readiness and settled practices for children's participation. However, more empirical studies with multiple methods and data sources are needed to find associations amongst ideas, developed practices and their potential outcomes, as Correia and others (2019) have suggested.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

J.H. presented the idea of the research and the use of L.T.'s model. J.H. implemented the data collection. J.H., T.K. and L.T. carried out the analysis. All authors (J.H., T.K., L.T. and N.H.) contributed to the conclusions of the results and to the writing of the manuscript.

Ethical considerations

This article followed all ethical standards for research without direct contact with human or animal subjects.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

For ethical reasons, the data that support the findings of this study are not openly available for people outside of the research group for reasons of sensitivity (e.g. human data). They are available from the project administrator, J.H., upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

References

Act on Early Childhood Education and Care (540/2018), viewed 07 February 2021, from https://www.finlex.fi/en/laki/kaannokset/2018/en20180540.pdf.

Alasuutari, M., 2014, 'Voicing the child. A case study in Finnish early childhood education', Childhood 21(2), 242-259. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568213490205 [ Links ]

Alderson, P., 2008, Young children's rights. Exploring beliefs, principles and practice, 2nd edn., Jessica Kingsley, London.

Almqvist, A.-L. & Almqvist, L., 2015, 'Making oneself heard - Children's experiences of empowerment in Swedish preschools', Early Child Development and Care 185(4), 578-593. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2014.940931 [ Links ]

Bae, B., 2009, 'Children's right to participate: Challenges in everyday interactions', European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 17(3), 391-406. [ Links ]

Bae, B., 2010, 'Realizing children's right to participate in early childhood settings: Some critical issues in a Norwegian context', Early Years 30(3), 205-218. [ Links ]

Brotherus, A. & Kangas, J., 2018, 'Leikkiympäristön haasteet ja rajoitukset lasten osallisuudelle', ['Challenges and restrictions of play-environments for children's participation'], in J. Kangas, J. Vlasov, E. Fonsén & J. Heikka (eds.) Osallisuuden pedagogiikkaa varhaiskasvatuksessa 2, [Participation related pedagogy in ECE 2], pp. 20-34, Suomen Varhaiskasvatus ry, Early Childhood Education Association Finland, Tampere.

Clement, J., 2019, 'Spatially democratic pedagogy: Children's design and co-creation of classroom space', International Journal of Early Childhood 51(1), 373-387. https://doi-org.ezproxy.jyu.fi/10.1007/s13158-019-00253-4 [ Links ]

Clark, A., 2005, 'Ways of seeing: Using the mosaic approach to listen to young children's perspectives', in A. Clark, A.T. Kjørholt & P. Moss (eds.) Beyond listening: Children's perspectives of their early childhood environment, pp. 29-49, Policy Press, Bristol.

CoE (Council of Europe), 2012, Recommendation CM/Rec (2012) 2 of the committee of ministers to member states on the participation of children and young people under the age of 18, viewed 02 January 2021, from https://rm.coe.int/168046c478.

Coffey, A., 2014, 'Analysing documents', in U. Flick (ed.), The Sage handbook of qualitative data analysis, pp. 367-380, Sage, London.

Correia, N., Camilo, C., Aquiar, C. & Fausto, A., 2019, 'Children's right to participate in early childhood education settings: A systematic review', Children and Young Services Review 1000, 76-88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.02.031 [ Links ]

EDUFI, 2016; 2018, National core curriculum for early childhood education and care, Finnish National Agency of Education, Helsinki.

EDUFI, 2014; 2016, National core curriculum for pre-primary education, Finnish National Agency of Education, Helsinki.

Einarsdottir, J., 2005, '"We can decide what to play!" Children's perceptions of quality in an Icelandic playschool', Early Education and Development 16(4), 469-488. [ Links ]

Einarsdottir, J., Purola, A.-M, Johansson, E.M., Broström, S. & Emilson, A., 2015, 'Democracy, caring and competence: Values perspectives in ECEC curricula in the Nordic countries', International Journal of Early Years Education 23(1), 97-114. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2014.970521 [ Links ]

Emilson, A. & Folkesson, A.-M., 2006, 'Children´s participation and teacher control', Early Child Development and Care 176(3 & 4), 219-238. [ Links ]

Emilson, A. & Johansson, E., 2013, 'Participation and gender in circle-time situations in pre-school', International Journal of Early Years Education 21(1), 56-69. [ Links ]

Franklin, A., 2013, A literature review on the participation of disabled children and young people in decision making, VIPER Project, The Alliance for Inclusive Education, the Council for Disabled Children, the National Children's Bureau (NCB) Research Centre and the Children's Society, London.

Hart, R., 1992, Children's participation: From tokenism to citizenship, UNICEF, International Child Development Centre, Florence.

Horgan, D., Forde, C., Martin, S. & Parkes, A., 2017, 'Children's participation: Moving from the performative to the social', Children's Geographies 15(3), 274-288. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2016.1219022 [ Links ]

Ivrendi, A., 2017, 'Early childhood teachers' roles in free play', Early Years, 40(3), 273-286. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2017.1403416 [ Links ]

James, A., Jenks, C. & Prout, A., 1998, Theorizing childhood, Polity Press, Cambridge.

Kangas, J., 2016, 'Enhancing children's participation in early childhood education through participatory pedagogy', academic dissertation, Department of Teacher Education, Faculty of Behavioural Sciences, University of Helsinki, viewed 10 April 2019, from http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-51-1833-2.

Kettukangas, T., 2017, 'Perustoiminnot-käsite varhaiskasvatuksessa' [Concept of basic activities in early childhood education], Publications of the University of Eastern Finland, Dissertations in education, humanities, and theology, 110, University of Eastern Finland.

Kettukangas, T., Heikka, J. & Pitkäniemi, H., 2017, 'Lasten osallisuus perustoiminnoissa - varhaiskasvattajien arviointeja' [Children´s participation in basic activities - Assessments by educators], in A. Toom, M. Rautiainen & J. Tähtinen (eds.), Toiveet ja todellisuus. Kasvatus osallisuutta ja oppimista rakentamassa [Hope and reality. Education constructing participation and learning], Kasvatusalan tutkimuksia - Research in Educational Sciences 75, pp. 169-195, Suomen Kasvatustieteellinen Seura, Jyväskylä.

Kirby, P., Lanyon, C., Cronin, K. & Sinclair, R., 2003, Building a culture of participation. Involving children and young people in policy, service planning, delivery and evaluation, Research report, The National Children's Bureau, Department for Education and Skills, Nottingham.

Knauf, H., 2019, 'Physical environments of early childhood education centres: Facilitating and inhibiting factors supporting children's participation', International Journal of Early Childhood 51(1), 355-372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-019-00254-3 [ Links ]

Krippendorff, K., 2013, Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology, 4th edn., Sage, Los Angeles, CA.

Lansdown, G., 2010, 'The realisation of children´s participation rights. Critical reflections', in B. Percy-Smith & N. Thomas (eds.), A handbook of children and young people´s participation. Perspectives from theory and practice, pp. 11-23, Routledge, London.

Leinonen, J. & Venninen, T., 2012, 'Designing learning experiences together with children', Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 45, 466-474. [ Links ]

Lim, C. & Lim, S., 2013, 'Learning and language: Educator-child interactions in Singapore infant settings', Early Child Development and Care 183(10), 1468-1485. [ Links ]

Lundy, L., 2007, '"Voice" is not enough: Conceptualising Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child', British Educational Research Journal 33(6), 927-942. [ Links ]

Malone, K. & Hartung, C., 2010, 'Challenges of participatory practice with children', in B. Percy-Smith & N. Thomas (eds.), A handbook of children and young people's participation. Perspectives from theory and practice, pp. 24-38, Routledge, London.

Markström, A.M. & Halldén, G., 2009, 'Children's strategies for agency in preschool', Children & Society 23(2), 112-122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1099-0860.2008.00161.x [ Links ]

Mesquita-Pires, C., 2012, 'Children and professionals' rights to participation: A case study', European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 29(4), 565-576. [ Links ]

Nyland, B., 2009, 'The guiding principles of participation: Infants, toddler groups and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child', in D. Berthelsen, J. Brownlee & E. Johansson (eds.), Participatory learning in the early years: Research and pedagogy, pp. 26-43, Routledge, New York, NY.

Oswell, D., 2013, The agency of children. From family to global human rights, Cambridge University Press, New York, NY.

Owens, A., 2005, 'Involving children in program planning', Putting children first: newsletter of the National Childcare Accreditation Council (NCAC) 13, 6-8. [ Links ]

Patton, M.Q., 2015, Qualitative evaluation and research methods, Sage, London.

Rinaldi, C., 2005, In dialogue with Reggio Emilia, Routledge, London.

Rogoff, B., 2003, The cultural nature of human development, Oxford University Press, New York, NY.

Roos, P., 2015, 'Lasten kerrontaa päiväkodin arjesta', [Children's narratives of daily life in an early childhood education centre], Acta Universitatis Tamperensis, Tampere University Press, Tampere.

Rosen, R., 2010, '"We got our heads together and came up with a plan." Young children's perceptions of curriculum development in one Canadian preschool', Journal of Early Childhood Research 8(1), 89−108. [ Links ]

Salminen, J.E., 2013, 'Case study on teachers' contribution to children´s participation in Finnish preschool classrooms during structured learning sessions', Frontline Learning Research 1, 72-80. [ Links ]

Salminen, J. & Annevirta, T., 2016, 'Curriculum and teachers' pedagogical thinking when planning for teaching', European Journal of Curriculum Studies 3(1), 387-406. [ Links ]

Salminen, J. & Poikonen, P.L., 2017, 'Opetussuunnitelma pedagogisena työvälineenä' [Curriculum as a pedagogical tool], in M. Koivula, A. Siippainen & P. Eerola-Pennanen (eds.), Valloittava varhaiskasvatus. Oppimista, osallisuutta ja hyvinvointia [Captivating early childhood education. Learning, participation and wellbeing], pp. 56-74, Vastapaino, Tampere.

Sandberg, A. & Eriksson, A., 2010, 'Children's participation in preschool. On the conditions of the adults? Preschool staff's concepts of children's participation in pre-school every day', Early Child Development and Care 180(5), 619-631. [ Links ]

Sairanen, H., Kumpulainen, K. & Kajamaa, A., 2020, 'An investigation into children's agency: Children's initiatives and practitioners' responses in Finnish early childhood education', Early Child Development and Care 192(1), 112-123. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2020.1739030 [ Links ]

Sevón, E., Hautala, P., Hautakangas, M., Ranta, M., Merjovaara, O., Mustola, M. et al., 2021, 'Lasten osallisuuden jännitteet' [Tensions in children's participation], Journal of Early Childhood Education Research 10(1), 114-138, viewed 07 February 2021, from https://jecer.org/issues/jecer-101-2021-special-issue/. [ Links ]

Shier, H., 2001, 'Pathways to participation: Openings, opportunities and obligations. A new model for enhancing children's participation in decision-making, in line with Article 12.1 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child', Children and Society 15(2), 107-117, viewed 10 April 2019, from http://ipkl.gu.se/digitalAssets/1429/1429848_shier2001.pdf. [ Links ]

Shier, H., 2010, 'Children as public actors: Navigating the tensions', Children & Society 4(1), 24-37. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1099-0860.2008.00208.x [ Links ]

Shier, H., 2019, 'Student voice and children's rights: Power, empowerment, and "protagonismo"', in M.A. Peters (ed.), Encyclopaedia of teacher education (on-line early), pp. 1-6, Springer Nature, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-1179-6_27-1

Sinclair, R., 2004, 'Participation in practice: Making it meaningful, effective and sustainable', Children & Society 18(2), 106-118. [ Links ]

Theobald, M., 2019, 'UN Convention on the Rights of the Child: "Where are we at in recognising children's rights in early childhood, three decades on ...?"'. International Journal of Early Childhood 51(1), 251-257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-019-00258-z [ Links ]

Thomas, N. & Percy-Smith, B., 2010, 'Introduction', in B. Percy-Smith & N. Thomas (eds.), A handbook of children and young people's participation: Perspectives from theory and practice, pp. 1-7, Routledge, London.

Turja, L., 2017, 'Lasten osallisuus varhaiskasvatuksessa' [Children's participation in early childhood education], in E. Hujala & L. Turja (eds.), Varhaiskasvatuksen käsikirja [The handbook of early childhood education], pp. 38-55, 4th rev. edn., PS-kustannus, Jyväskylä.

Turja, L., 2018, 'Material environment and knowledge enabling children's participation in ECEC institutions', paper presentation, Childhood and materiality, The VIII conference on childhood studies, University of Jyväskylä, Jyväskylä, 8th May.

United Nations, 1989, The convention on the rights of the child, viewed 07 February 2021, from https://www.unicef.org/child-rights-convention/convention-text#

United Nations, 2006, General comment No. 7. Implementing child rights in early childhood, (CRC/C/GC/7/Rev.1), UN Office of High Commissioner for Human Rights, Geneva, viewed 02 January 2021, from http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/crc/docs/AdvanceVersions/GeneralComment7Rev1.pdf.

Venninen, T. & Leinonen, J., 2013, 'Developing children's participation through research and reflective practices', Asia-Pacific Journal of Research in Early Childhood Education 7(1), 31-49. [ Links ]

Virkki, P., 2015, 'Varhaiskasvatus toimijuuden ja osallisuuden edistäjänä' [Early childhood education promoting agency and participation], Dissertations in Education, Humanities, and Theology 66, University of Eastern Finland.

Vygotsky, L., 1978, Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes, Harvard University Press, Boston, MA.

Weckström, E., Lastikka, A.-L., Karlsson, L. & Pöllänen, S., 2021, 'Enhancing a culture of participation in early childhood education and care through narrative activities and project-based practices', Journal of Early Childhood Education Research 10(1), 6-32, viewed 10 February 2021, from http://jecer.org/fi. [ Links ]

Woodhead, M., 2010, 'Foreword', in B. Percy-Smith & N. Thomas (eds.), A handbook of children and young people's participation: Perspectives from theory and practice, pp. x-xxii, Routledge, London.

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Titta Kettukangas

titta.kettukangas@uef.fi

Received: 28 Dec. 2021

Accepted: 01 June 2022

Published: 19 Aug. 2022