Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Childhood Education

versão On-line ISSN 2223-7682

versão impressa ISSN 2223-7674

SAJCE vol.12 no.1 Johannesburg 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v12i1.1043

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Finding myself by involving children in self-study research methodology: A gentle reminder to live freely

Ntokozo S. Mkhize-Mthembu

Department of Higher Education, Faculty of Education, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pinetown, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: This article describes my exploration of social and emotional learning as a primary school teacher in a Grade 4 classroom.

AIM: This article aimed to illuminate how I improved my teaching practice through valuing and listening to children's voices.

SETTING: I am a teacher at a primary school in the Umlazi education district, KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa. As a PhD candidate, I explored social and emotional learning in a Grade 4 classroom from a scholarly perspective.

METHOD: I present a detailed description of the methodological interactions and the theoretical underpinning that guided my interactions with the Grade 4 study participants. I documented the lessons, which were audio-recorded and photographed, in my teaching development portfolio. By employing self-study research and adopting a sociocultural theoretical perspective, I explored the principles of social justice. The importance of working collaboratively with children in a primary school educational setting to make sense of both the teacher's and the learners' collective and individual experiences is emphasised. The methodology included working with critical friends to help me uncover different ways of making sense of my research and to enhance my own learning about teaching.

RESULTS: The findings affirm that young children's voices need to be foregrounded to enhance teaching and learning practices. Children's dignity and perspectives need to be acknowledged as they are the key contributors to and recipients of educational processes

CONCLUSION: The study affirms the importance of crediting young learners' diverse perspectives and lived experiences in classroom interactions and asserts that this obligates teachers to listen to children emotively and consciously.

Keywords: children's voices; collaborative learning; emotions; self-study research; social and emotional learning; social justice.

Introduction

The larger study on which this article is based aimed to discover ways of improving my teaching practice. In this process, I became deeply conscious of the importance of valuing and listening to children's voices during classroom interactions. I learned that teachers should embrace opportunities to see themselves through their learners' eyes as this enhances their teaching practices to ensure that learners' social and emotional needs are accommodated. The self-study process allowed me to find myself and understand my practice as I acknowledge the children's voices, which in turn enriched the teaching and learning interactions that occurred in the classroom with deep social value. I documented 10 lessons and continuously wrote journal entries about my insights and experiences as my learners engaged in planned written and drawing activities. The lessons were also audio-recorded with the permission of the learners and their parents. This self-study project allowed me to explore my own learning as a teacher from a social and emotional perspective as the study was underpinned by the sociocultural theoretical framework. This theory emphasises the importance of working together in educational settings to make sense of collective and individual experiences. I also engaged with three critical friends who helped me to uncover different ways of making sense of my research and to enhance my learning and teaching. These friends offered constructive criticism and continuously identified gaps in my approach, which I attended to. The findings affirm that school children's voices should be foregrounded in the educational context in ways that respect their dignity and perspectives and acknowledge them as key contributors to their learning. Giving credit to young children's voices was accomplished by means of emotive dialogues and by reflecting on the insights that could be gained from our conversations and other interactions. I also focused on my learners' experiences beyond the classroom.

The main research question was: 'How can I improve my teaching practice by valuing and listening to children's voices'? I wanted the classroom atmosphere to be infused with positive emotions and ideas, and my learners to embrace values that stimulated their learning. It was important that they learnt to be emotionally mature at an age-appropriate level and that they would face new challenges confidently. I hoped that they would be capacitated to interact with others in a compassionate, kind and respectful manner.

During the study, I needed to acknowledge and be conscious of the many contextual factors that might influence the teacher-learner relationship inside the classroom and in the outdoor areas where I presented some lessons. I was inspired by Newberry (2013:16) who believed that teachers '… must be given opportunities to reflect so that the decisions [they make] that lead to relationships are based on accurate information rather than quick impressions'. It is a fundamental requirement that we tap into our learners' social and emotional needs, and that we are attentive to and empathetic towards them at all times (Newberry 2013). I envisaged that my mindset and relationships with my learners would be newly forged by their unique personalities, their need for supportive relationships, and the positive emotional energy they would require and exude. I took heart from Panayiotou, Humphrey and Wigelsworth (2019) who enlightened the point that emotional knowledge may nurture effective learning through collaboration in the classroom, which would ultimately result in learners' successful emotional development and academic achievements. I had to be conscious of all these factors when I planned to explore social and emotional learning. I wanted to be responsive to my learners' social and emotional challenges regardless of their diverse academic abilities or character traits.

In this article, I first deliberate on my quest for positivity through an exploration of social and emotional learning in my classroom. I then elaborate on the principles of social justice and how these assisted me in acknowledging and giving credibility to my learners' voices. I also discuss how the creation of a learning community encouraged a sense of belonging in the classroom. Furthermore, I discuss the sociocultural perspective and how this illuminated my understanding of my own and my learners' experiences. I conclude by sharing some of my most valuable learnings regarding fore fronting my learners' voices and by offering recommendations based on the new insights that I gained.

A quest for positivity

Going on a 'quest' is a voyage that an intrepid traveller undertakes to explore the unknown. I thus commenced this research journey by venturing into the unknown, understanding that it would be a new experience for the learners and myself. I was cognisant that my learners came from different backgrounds and adhered to different belief systems derived from their parents and home environments. I was sensitive to the fact that some might know how to express themselves and identify with others, while some would be shy and aloof. I had to acknowledge that we were all emotional beings who experienced joy, sadness and fear. I accepted that some learners tended to be shy and embarrassed when they had to share information about their social backgrounds, and that many might lack emotional security. I therefore wanted to construct a classroom culture that would radiate positivity so that social and emotional learning would instil the values of compassion, love and tolerance in my learners. Bradford (2021) highlighted the importance of acknowledging multiple perspectives in a classroom and stressed that it is pivotal to recognise and respect the different views of learners in such a setting. I knew that my learners' different personalities would not only require different approaches to guide their choices but also that these choices would have consequences for them for the rest of their lives.

Social justice

Crosby, Howell and Thomas (2018) argued that instead of incriminating learners for their responses to their situations, teaching has to be embedded in a social justice perspective that seeks to abolish domineering systems from the school. I decided to adopt a social justice stance in my teaching because I was conscious of my learners' traumatic experiences and wanted to respond to them sensitively. I also wanted to see them as equal participants in my study.

I adopted a stance that was inspired by Crosby et al. (2018:21) who explained that learners learn when they are provided with opportunities '… to practice social skills and empathy within the lesson plan'. I thus resolved to focus on activities that would encourage assertiveness, non-violent communication and 'fair fighting' through debate and reflection. I thus planned, amongst others, the writing and journaling of activities that would allow my learners to discuss their stress and other emotions in a frank and non-coerced manner.

Creating a learning community in my Grade 4 classroom

As the teacher, I needed to play a fundamental role in nurturing social development. Northfield and Sherman (2004) explained that creating opportunities for interaction with peers is fundamental to acquiring social aptitudes. A primary foundation of social knowledge in children of all ages is their relations with other children. I understood that my learners might experience some dilemmas as they would constantly try to find themselves and preserve their identities, even if it meant getting negative attention rather than no attention at all. Classroom teachers thus need to create an environment that nurtures sociability in the classroom community.

Schools need to engender a sense of belonging within the school in general, and in smaller classroom communities in particular, by balancing children's need for individual identity and autonomy with sound social relationships in which needs of others are also considered: 'Teachers can influence peer relationships by establishing values, standards and norms in a caring classroom that is supportive of strong nurturing relationships' (Northfield & Sherman 2004:294). I wanted my learners to understand that they were worthy of love and care, which are values that need to be carefully negotiated in collaboration with other teachers and classmates. Our actions, how we perceive ourselves and how we treat others stem from the values and central beliefs we grow as we mature in our relationships with others.

The sociocultural theoretical perspective

I adopted a sociocultural theoretical perspective in the broad study. Kelly (2006) clarified that according to the sociocultural view of learning, learners bring conceptual resources to the classroom based on or adapted from the cultural background they were immersed in and the beliefs they imbibed even before attending school. Furthermore, Luthuli, Phewa and Pithouse-Morgan (2020) explained that taking a sociocultural approach in working collaboratively with people from different backgrounds could nurture beneficial exchanges in terms of personal understandings and social and cultural relations. Kelly (2006) stated that learning can be enhanced when resources are provided in the classroom that consider and build on learners' conceptual resources. I thus used a variety of teaching resources to integrate social and emotional learning. For example, I focused on using indigenous musical instruments in my teaching. This was an exciting approach that my learners related to and enjoyed. Introducing indigenous resources into a learning environment can link classroom concepts to learners' daily encounters outside the classroom, thus making learning more interesting for them (Nkopodi & Mosimege 2009).

Learning at school requires a classroom community from whom individuals learn and with whom they share insights. According to Gerhard and Mayer Smith (2008:5), sociocultural theories of learning '… are based on the assumption that learning is not an individual activity, but rather a social phenomenon'. This presupposes a relationship that engenders learning through interaction and collaboration. Understanding this notion encouraged me to devise collaborative tasks and allow my learners to share ideas and experiences.

According to McMurtry (2015:1), 'most human cognitive skills originate in social interactions, practices and tools'. When I read this statement, I realised that learning occurs through social interactions and when learners communicate with their parents, family members, fellow learners and friends. I realised that my teaching practices needed to be shaped in such a way that they encouraged my learners to form positive relationships in the classroom. These relationships would, in turn, facilitate social interaction and active participation in the learning tasks I devised. I also needed to use different tools that would encourage them to work collaboratively such as observation, listening and conversations. I fervently hoped that my learners and I would embrace such relationships and activate them in the classroom. John-Steiner and Mahn (1996) agreed that learning occurs through social interaction as we learn best by interacting with our social environment. I thus realised that my learners would learn best by participating in classroom discussions, interacting with their peers on the playground and communicating with people around them.

People learn through their lived experiences (Pithouse-Morgan, Deer-Standup & Ndaleni 2019) and by adopting the sociocultural theory I came to understand and embrace this notion. Samaras and Freese (2006:50) argued that this theory is constructed on the belief that humans are profoundly influenced by their social and historical backgrounds that facilitate their experiences. In my view, the sociocultural theory encourages the formation of learning communities in which all role-players work together, and it was this kind of culture that I wanted to instil in my classroom.

Research methods and design

I employed a self-study research methodology. Pithouse, Mitchell and Weber (2009) argued that self-study methodology is frequently used by teacher educators and teachers who are studying their practice. By employing the self-study methodological approach, I imagined that I would be allowed to reflect on and improve my teaching approaches and methods. I also envisaged that this methodology would facilitate my exploration of social and emotional learning in my Grade 4 classroom.

Self-study research employs diverse methods such as arts-based and memory work, and the investigator's personal history in order to respond to the research questions (Samaras 2011). I employed the personal history and arts-based self-study methods in this study. Data were thus generated, amongst others, by means of journal and poetry writing and critical reflection. By adopting these methodologies, I was enthused to question my own educational and learning experiences as a child and teacher. LaBoskey (2004:829) argued that '… the challenge for teacher educators is … to provide ways for students to articulate and interrogate their personal histories and resultant understandings'. I also encouraged my learners to formulate mutual goals and to cooperate through classroom discussions. Hausfather (1996) suggested that collective commitment and shared problem-solving activities are necessary to aid cognitive, social and emotional trading, which means that learning in the zone of proximal development (ZPD) does not only require the internalisation of exterior lessons but also the utilisation of shared activities where learners are interpersonally engaged. Vygotsky (1978) described the ZPD as:

[T]he distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem-solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers. (p. 86)

Thus, by interacting with my learners in various activities, I created opportunities that directed and scaffolded their social and emotional interactions and hence their learning. I used ice-breakers with tasks such as, 'Rate your day from 1 to 10 and tell us why you are giving your day a low or high rate'. I did not see my learners as empty vessels that I needed to fill but acknowledged that they had already acquired knowledge. I thus needed to guide them to acquire new knowledge from a platform where they could identify their emotions and express themselves.

I employed a qualitative research approach to explore my own and my young participants' experiences related to social and emotional learning. Denscombe (2010) posited that qualitative researchers aim to understand fundamental explanations and impulses that enlighten a particular research topic. It permits the researcher to obtain fresh insights into the topic being explored and yields ideas that clarify the research problem. Furthermore, Denscombe (2010) stressed that the qualitative researcher defines and illuminates relationships, individual experiences and group norms.

Firstly, I needed to explore my own emotions before looking at my youthful participants' feelings and experiences. Collins and Cooper (2014) argued that in qualitative research, emotional intelligence reinforces the researcher's ability to relate to participants and competently listen to and understand their lived worlds. By following this advice, I explored my own and my participants' feelings and learnt by wading respectfully and unintrusively into their life experiences. Furthermore, Collins and Cooper (2014) highlighted that qualitative research is unmatched in scope because it entails both emotional development and solid collaborative skills to gather data. This is carried out by listening to the stories of others and using their words to make meaning. Even though my participants were young, I sought to understand their perceptions better and to discover how they related to their social and emotional learning.

I envisioned that the qualitative research approach would allow me to gain greater emotional and social maturity. Brandenburg and McDonough (2019) argued that our reflections on our narratives in self-study research regarding power dynamics allow us to be better teachers, mentors and advisors as we become sensitised to power flow. I did not want to take advantage of my teaching position, so I encouraged my learners to participate actively in our lessons. This empowered me to better understand the social collaborations that I explored.

To facilitate my professional growth over a selected period (Samaras 2011), I concertedly documented my learning and experiences. For this I used a developmental portfolio as it allowed me to record and unpack my teaching practices and professional growth.

Ethical considerations

I adhered to all ethical considerations as required for studies of this nature. I approached my principal and requested her permission to explore social and emotional learning in my Grade 4 classroom. Permission to conduct the study was granted by the Research Ethical Committee of the University of KwaZulu-Natal. Upon receiving all the gatekeepers' letters of approval, I presented the research proposal in writing and was granted permission to proceed with the study.

I also sought and received written permission from the learners' parents to involve their children in this study. To ensure confidentiality, the learners' class work is presented under pseudonyms when I refer to particular learners and their faces are not visible in the photographs.

Involving children in self-study research

I explained to my learners that I would involve them in a self-study project and value their ideas and participation. The letters I sent to the parents/guardians offered a clear explanation of the study's aims and assured them that their children would not be compelled to participate. I iterated that neither participation nor non-participation would affect the learners' academic results or my attitude towards them in any way, and that they could withdraw from the study at any time. Also, they were assured that their diverse beliefs and value systems would be respected and approached ethically. I received learners' assent verbally, I explained that it was not compulsory to participate and that they could stop participating at any time.

According to Graham, Powell and Taylor (1996:335), 'children involved [in research] are entitled to justice' and I thus resolved to ensure that my learners would not be harmed in any way. Because the learners who participated knew that their parents supported what we would do, a harmonious relationship was created between the learners and me. I commenced by clearly explaining at an age-appropriate level what I meant by social and emotional learning and this helped me to manage the daily challenges that occurred, to adopt an optimistic mindset and to establish healthy relationships. Most learners seemed intrigued, but some seemed doubtful initially. Of the 41 learners in my class, 40 agreed to participate with their parents' permission. Only five withdrew during the research activities. As I respected this decision, I did not probe for reasons.

Data generation and analysis

Pithouse-Morgan and Samaras (2020) stated that self-study researchers may use numerous methods to generate data. After a comprehensive literature review in the self-study field, I embraced this opportunity by utilising multiple data generation tools, particularly journal writing, artefact retrieval, photographs, poetry and audio recordings of my lessons. My purpose was to unearth everything I could about social and emotional learning and utilising these tools would, in my view, enrich the findings regarding social and emotional learning. By utilising these tools, I was able to apply my knowledge and experiences to the activities I devised and I endeavoured to offer my learners opportunities to unwittingly and sometimes deliberately express their emotions regarding their social and emotional experiences.

Data generation

Journal writing

Journal writing entails writing down one's thoughts and personal insights. It can also be used to reflect on daily experiences and to record questions on professional topics. Masinga (2012) argued that journal writing facilitates a delicate reflection on our work and experiences, which exposes our deepest thoughts and even our vulnerabilities. Journal writing was thus a tool to document my learning journey and record my sincere feelings and vulnerabilities. In fact, I shared my deepest feelings without holding back.

Poetry

Furman, Coyne and Negi (2008) argued that writing poetry is a valuable process of self-discovery and self-reflection. It opens new perspectives on the world and encourages us to reflect on emotions and feelings that have previously been unexplored. My learners thus had opportunities to reflect on their previously unacknowledged emotions and be genuine and honest about their feelings and life experiences.

Photographs

I took photographs to record and facilitate close observation of my learners' interactions as I could capture distinctive and meaningful moments. Moskal (2017) explained that visually supported research allows children to be active in the research process and reverses the typical role of having research carried out about them and not with them. I took photos of my learners hugging trees and writing how they felt, in these activities, as active research participants. As children are often silenced and marginalised in society and research, these activities enhanced social justice.

Audio recordings

Audio recording my lessons supported my narrative writings about them. Masinga (2012) stated that audio recordings can play a fundamental role in discussions and can clarify what participants said or intended to say. Moreover, the audio recordings were invaluable in unpacking the data and my reflections on the findings. I was able to replay and listen to critical points and to analyse my learners' responses, and I could, upon reflection, detect the real emotion behind these responses.

Data analysis

I employed thematic analysis to evaluate the data. Braun and Clarke (2006) stated that inductive analysis occurs when data-driven themes are identified. Braun and Clarke (2006:83) emphasised that an inductive approach means that '… the themes identified are strongly linked to the data themselves'. Inductive reasoning is thus based on learning from experience as patterns, similarities and consistencies in experiences are used to reach conclusions. I thus generated meanings from the data set to identify patterns and relationships on which my conclusions were based. I searched for similar patterns and identified relationships amongst the rich body of data I had collected. Braun and Clarke (2006) advised that it is important to review data and identify where elements collate and how they are relevant to the topic of a study.

These themes emerged from two primary data sources, namely the classroom and my memories. I addressed the following three themes: (1) social and emotional learning promotes self-awareness, (2) social and emotional learning cultivates positive relationships and (3) social and emotional learning develops resilience and an optimistic approach to life.

Social and emotional learning promotes self-awareness

The following extract from my reflective journal demonstrates how my self-study research allowed me to grow in self-awareness and identify and to respect others' feelings. This was an essential learning point about social and emotional learning. This extract reflects my growing self-awareness: Retrospective Journal Entry:

Looking back, I understand that children need to be allowed to engage in different real-life experiences. I think this will enable them to understand different relationships. I realise that social and emotional learning is essential for discovering a sense of self when learners begin to uncover and explore their identities. My learners should thus develop holistically by taking responsibility for their surroundings, relationships, and emotions. I also acknowledge that childhood experiences are not acquired in isolation, but that they are entrenched in our everyday activities and encounters. I look forward to creating experiences for my learners that will warm their hearts and enrich their minds. (Mkhize 2020:147)

Social and emotional learning promotes self-awareness and freedom. Along my journey of social and emotional learning, I was able to identify and understand different emotions and both pleasant and unpleasant feelings. Swartz (2017) outlined that self-awareness exposes one's feelings, values and know-how that all influence behaviour. I learnt to regulate my feelings and behaviours, and not suppress my emotions either inside or outside the classroom. This understanding now gives me the power to empathise with others, the willingness to understand different emotions and the open-mindedness to respect different backgrounds and life experiences.

The following extract is from an audio-recorded lesson. Figure 1 illustrates an activity that promoted my learners' self-awareness and thus their social and emotional learning. After reading the text titled: The people who hugged trees, my learners had to express what they felt strongly about and many responses were enchanting as they were infused with emotion and honesty:

Jessica said: 'I feel strongly about my family because they mean everything to me, and I love them with all my heart. I will never be the same without them. They make me happy.'

Tristen conveyed that he also felt strongly about certain things when he asserted:

[I] feel very strongly about myself, God and my family. The reason is that God made me who I am, and my family supports me. That is why I feel strongly about God and my family.

I asked Tristen to explain why he felt strongly about himself. He was a bit puzzled and reluctant at first but then responded, 'Umm … I feel strongly about myself … Ummm … to be honest, I don't know why I feel strongly about myself.'

My learners showed awareness of their feelings when they expressed who they felt strongly about and why. This was a vital indication of self-awareness, as being self-aware also means identifying how other people see you.

Theme 2: Social and emotional learning cultivates positive relationships

I realised that social and emotional learning requires meaningful dialogues and working collaboratively. I also understood that knowledge is acquired in a learning community. The image in Figure 2 illustrates my understanding that learning is not isolated from cultural, religious and social experiences. I was intrigued to engage with my learners and gain knowledge from their experiences and thoughts. When presenting my collage, I explained the following:

Ntokozo: 'This is a picture of a family. I do not want to isolate learning within a classroom only as I am conscious that learning takes place within our cultural and social backgrounds that we share within our social settings or communities. I also think this image is related to a socio-cultural perspective as it symbolises that learning and teaching take place collaboratively.'

I apprehended that crucial abilities such as having self-control, self-awareness and managing emotions can cultivate positive relationships. Durlak and Weissberg (2018) advised that social and emotional learning has been intellectualised in many ways, such as being a tool to gain and effectively apply knowledge and attitudes. My learners and I had to engage in social and emotional learning daily and adopt a positive approach to learning. We also had to progress cautiously and consider different social backgrounds and experiences such as trauma, loss and religious beliefs. I longed for my learners to feel and display compassion for others, create and preserve encouraging relationships and make decisions for which they would accept accountability.

The sociocultural perspective also refers to channelled participation (McMurtry 2015). I thus saw myself not only as a mediator but also as a participant in the learning process. Gerhard and Mayer-Smith (2008) explained that from a sociocultural perspective, community building and collaboration are vital for development. Furthermore, we can tap into our learners' experiences and discover who they are through involvement and participation. In my view learners who actively participate, gain new social and emotional skills and experiences through evocative, collaborative activities, especially when assisted by a non-intrusive but more experienced other.

I yearned to cultivate relationships in a pervasive and caring manner. Social and emotional learning allowed me to live in an environment where I encouraged justice, adopted an optimistic attitude and found freedom. Figure 2 symbolises situations where the heart of justice unfolds and where love and compassion thrive. It also symbolises friendship as it is here where the foundation of sound relationships is forged within the family circle.

Social and emotional learning undeniably cultivates healthy relationships that are spirited and inspirational. Figure 3 symbolises a safe and joyful relationship within the family. I love the fact that this family represents happiness and contentment as mirrored by their facial expressions. Swartz (2017) revealed that having relationship proficiencies means listening emotively, collaborating with others and resisting negative social pressure. Social and emotional learning fostered a resilient learning community in my classroom as we shared heartfelt feelings for one another. My learners were able to embrace hope, and I knew that I would open the door to a journey of learning and development during which they would flourish. Their relationships needed to encompass love, acceptance, support and safety. I understood that social and emotional learning would embolden them to build nurturing, close relationships, that would involve being compassionate and loving.

Social and emotional learning develops resilience and an optimistic approach to life

By exploring the social and emotional aspects of my personal memories and my Grade 4 learners' classroom activities, I am able to share some stories that relate to my learners' activities and responses and the learning that occurred through my own childhood experiences. The spirit in the classroom was enriched by our joyful commitment to our respective learning and teaching activities and our relationships. I learned that being optimistic creates openness, honesty and sincerity. Durlak and Weissberg (2018) suggested that social and emotional competencies aid learners' academic performance, facilitate positive social behaviours, and strengthen social relationships. It was important to apply social and emotional learning in my teaching to minimise behavioural problems and psychological grief.

I devised activities that encouraged my learners to express themselves. For instance, before starting a lesson I asked my learners to rate their day from 1 to 10. This ice-breaker was effective because it allowed my learners to interact and share their emotions about what they had faced that day. As I also shared what I had experienced that day, we identified parallel experiences and feelings and talked freely about how we had confronted our challenges and responded to our emotions. For example:

San stated: 'I rate my day 3 out of 10. I was ill-mannered and mischievous in the hall this morning.' I asked, 'Oh, so what happened'? San replied, 'Mr. S took away my first break. I felt bad and embarrassed.'

It was courageous of San to be honest about how he felt about his day and to acknowledge that his behaviour had been unacceptable. His response depicted his growing sense of responsibility and accountability. This lesson allowed me to give my learners a voice and to help them build on their self-perspective. They seemed to realise that it was necessary to acknowledge their mistakes and take responsibility. At the time, guiding my learners to self-awareness was a work in progress from which I also had to learn if I wanted to grown and improve my teaching. I had to be hard on myself at times.

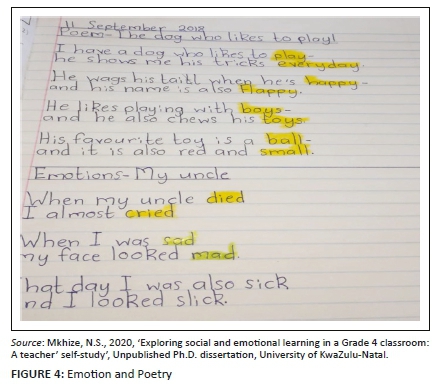

I also encouraged my learners to explore what they had learned socially and emotionally by encouraging them to write poetry (see Figure 4). Here is an example of one such poem:1

In love

Hello, Thabo is my name, I have not told anyone, but I am in love.

She is bright like a holy dove

Soon, I will have time

In the future, she will be mine

When I am in my 20s in spring

I will give her an engagement ring

I have not told you, but she is kind

Now you see that I am love blind.

-Thabo Langa-

Christelle wrote the following:

I prompted the learners to write poetry by encouraging them to reflect on their lives, think about their feelings and notable people and to remind themselves of the challenges they faced. I also encouraged them to focus on a single memory such as a colour, a taste and even music to evoke their emotions.

My learning

At the beginning of each lesson, we reflected on the previous lesson. I also shared some of my thoughts as my learners needed to perceive me as a 'partner' who shared their experiences or who had her own. Flewitt (2005) stated:

[T]he ethical solutions I found often resulted from sharing my reservations and fears with the research participants, and it is my firm belief that this sharing approach significantly enhanced the quality of the overall study. (p. 564)

When I emulated this advice, it opened the door to clarity and helped me interpret parts of lessons I might have misinterpreted or assumed.

The journal entries of the learners also opened my mind to the discoveries and emotions that prompted their social and emotional learning. At the end of each lesson I highlighted the need to work cooperatively and reiterated how important it was to adopt positive values such as compassion, thoughtfulness and resilience. Shabani (2016) illuminated the idea of shared scaffolding, which is rooted in Vygotskian thinking. This notion advocates that the group ZPD is larger than that of the individual, meaning that working together is beyond what each individual achieves alone. This philosophical stance assisted me in reflecting on how vital assenting and collaborative relationships serve as tools that facilitate the social competency to manage and identify emotions.

A beaming light and hope: Learning with children

In my conscious engagement with Grade 4 learners to explore social and emotional learning, I was constantly aware that these young learners reminded me to draw courage from my inner strength. They were passionate about life and making a positive impact on society. They taught me that power lies in believing in oneself and having the courage to try something new, even if it is daunting. We embarked on an emotional journey and fed our emotions with optimistic thoughts. I was eager to find new, meaningful ways of teaching and learning, and in this process the sociocultural perspective was invaluable. It compelled me to acknowledge my learners' background knowledge and I became fascinated with their uninhibited way of living. John-Steiner and Mahn (1996) stated that in classroom settings, cooperative learning and discovery are embedded in the culturally shaped value systems that learners bring to school. I was alerted to this insight and I saw my learners as crucial contributors to educational change.

I also appreciated the insights the sociocultural theory enlightened and the support and validation it brought to my research. John-Steiner and Mahn (1996:204) explained that the sociocultural perspective '… can thrive with the continued and at times discordant, articulation of the many voices of this thought community'. This process enhanced my relationship with my learners and I was able to learn valuable lessons from them as I saw them as active agents within the sociocultural community and not merely as empty vessels that needed to be filled. In turn, my learning allowed them to express themselves freely and even to protest against or dispute specific topics. It was a liberating experience to let my learners drive parts of my research with their own experiences. Children are undoubtedly invaluable in research and their voices need to be considered and recognised in society.

In my search for wisdom about social and emotional learning, I did not want my narratives to overshadow those of my learners. This meant that I sometimes had to mute myself and listen attentively to what they said. This gave them a chance to form healthy relationships and relate to the world around them. It was imperative that I consistently uttered words of affirmation as my learners flourished on positive feedback.

Reinventing myself through research that involved children

When I worked with these learner participants, I drew knowledge and insight from my personal and professional experiences and infused my teaching with this knowledge. I hoped this would enhance my expertise as a professional and strengthen my relationship with my learners. John-Steiner and Mahn (1996:202) argued that 'analysing how students work, as well as acknowledging and attempting to understand the cultural conditioned knowledge they bring to the classroom, can … lead to effective teaching'. I thus critically pondered my learners' voices and analysed my findings to gain new insights by looking at my subjects through the sociocultural lens. I also reflected on how this theoretical perspective on learning supported my understandings and discussions of the themes that emerged from the data.

I was able to identify who I was as a teacher as I was eager to understand my own emotional and social framework. I was invigorated to reflect on my teaching and recognised that self-awareness was an ongoing journey built on experience, self-reflective questions and acknowledged emotions. It was thus vital that I did not disregard my own feelings even in turbulent times. I also became conscious that self-awareness offered autonomy. When we are aware of our emotions, we respond and react in certain ways to a given situation. In other words, I learned to manage my feelings in an orderly manner. Self-awareness is undeniably a building block of social and emotional learning.

By acknowledging that self-study research learning can promote self-awareness, I faced the challenge to identify my learners' unique skills. Some of them were still inclined to imitate their friends or popular classmates and I therefore had to devise creative ways to determine what influenced the decision-making of some individual young learners. In a class of 41 learners, it was sometimes difficult to maintain personal contact whilst also promoting self-awareness in every learner. I thus believe that my exploration of social and emotional learning through poetry and journal writing opened doors through which my learners and I could venture to share moments of genuine amusement, self-inquiry, humour, imaginative visions and also uncertainty. I became aware that my teaching and own learning were enriched by creativity and novelty, and were deepened by collaboration.

I discovered that it was fundamental to establish mutual respect and forge positive relationships. I became mindful of creating a sense of community and belonging in my classroom. It was imperative that I did not dismiss my learners' emotions or marginalise their issues. I thus prevailed by providing support and creating an intensive learning atmosphere in which I treasured diverse insights and social backgrounds. I also realised that it was disturbing when I engaged my learners in dialogues that made them feel uncomfortable and apprehensive. It was thus incumbent upon me to build a welcoming atmosphere and learning environment in my classroom for the social and emotional enrichment of my learners.

It was in this atmosphere that my learners were able to forge healthy relationships on which we built a resilient foundation for teaching and learning. I became enthused as an activist for social change and justice within this valued learning community. My learners epitomised the power of diversity and taught me to recognise and value different human experiences and perspectives.

Challenges, tensions and complexities in self-study research involving children

A problem I encountered was that some of my learners' parents were hesitant to allow their children to participate in the study as they did not understand the nature of this investigation despite my explanations and assurances. I tried to encourage these parents and guardians to consider giving their consent by explaining how important this study would be for improving my teaching practice that would be to the benefit of their children. Eventually, only a very few refused their consent or withdrew their children from the study. Nevertheless, I treated all the learners with the same level of respect and ensured that data for the study thesis would reflect only the engagement of those learners whose parents had given their consent.

I vividly recall my lesson on bullying that explored the impact of this phenomenon on my learners' growth and emotions. They all admitted to having been victims of bullying and that they had also bullied others, primarily as a defence mechanism. It was a thought-provoking lesson as I listened emotively and had to hold back tears when a learner narrated her experiences that reminded me of my own broken spirit in my childhood. Taylor and Larson (1999) elucidated that by joining in discussion, learners can cultivate respect for different viewpoints, appreciate differences and learn to cope with powerful feelings. I thus had to develop sensitive ways of expression when addressing topics my learners opposed. It was vital that I encouraged positive self-talk, insisted on peaceful conflict resolution and found ways to deal with bullying. At times I battled to learn more about my learners' daily struggles, fears and what they did not like about themselves as this was a large class and some were reticent and shy. However, I watched in awe as powerful emotions were revealed (and also healed in some instances) in my classroom that became a powerhouse of confessions of how bullying affected these young, vulnerable learners.

In dealing with bullying, there were professional psychological resources available to the learners and myself to deal with such emotions. The school had a social worker who supported the learners and helped them cope with overwhelming feelings, which she did professionally and compassionately. She made referrals in cases where the learners needed additional psychological help or a medical doctor. The social worker also strengthened the social and emotional development of the learners by engaging with other teachers and learners and parents. This collaboration encouraged community collaboration and filled the gaps that occurred when teachers inadvertently overlooked a child's needs or took their well-being for granted.

I realise now that bullying occurs in complicated spaces and that the phenomenon is fraught with power struggles that are often indiscernible to school management teams and teachers. As a result, I revisited my lesson on bullying quite frequently as I became conscious of the feelings of defencelessness, powerlessness and vulnerability that were evident in some of my learners' stories.

Establishing a solid relationship with all my learners was a challenge as I found myself unconsciously being sympathetic and attentive to the group of more outspoken learners. Bradford (2021) posited that listening first-hand to children's feelings about their experiences of exclusion and rejection is heart-wrenching. I agree, as I often had to remind myself to remain calm and open to their emotions so that they would feel safe to share their stories. What seemed meaningless to me was potent and absorbing in their young minds. I constantly had to remind myself that social and emotional learning is for everyone. I now realise that the more teachers are willing to bond with their learners, the more efficient learning and teaching become. Taylor, Newberry & Clark (2020) pointed out that a deep concern for learners' development is critical in classroom interactions. Cohen and Marans (1999) cautioned that numerous children in our classrooms are in jeopardy of becoming 'stuck' academically, socially or emotionally. I was thus mindful that it would be essential to know their individual capacities before I could become effective as a teacher.

Various educational specialists have argued that it is vital to understand who our learners are developmentally, academically, psychologically and socially (Cohen & Marans 1999). However, the social and emotional development of many learners unfortunately occurs in environments that cannot provide the sense of security that is vital for young children, and it is therefore the teacher's responsibility to fill this space.

Teachers should not assume that young learners think alike or belong to a harmonious group. I know this because I needed to identify their individual needs and quirks, and I was accountable for the emancipation of my learners and for protecting them against any physical and emotional harm. All people are different and therefore learn and react differently to emotional prompts. So, I had to step into my learners' minds to discover how they interpreted the world around them and what they found enthralling and vital in their daily lives.

Another challenge that I faced was that I had to ensure that my study was consistently aligned with the theoretical perspective that I employed. It was initially a challenge to triangulate the literature, the theoretical perspective and the data, but as I grew in experience this process was mastered. I constantly revisited the research questions and collated different perspectives and resources, which was a process that enhanced the validity of the study.

My learners' experiences of participating in the study

I can describe my learners' social and emotional learning as a journey that taught them to see themselves as walking resources that should never be underestimated. They filled my classroom not only with a tangible spirit of positivity but also with sadness as we experienced it as a safe space for both genuine chuckles and tears. In brief, social and emotional learning allowed us to be raw and authentic about our life experiences.

My learners' knowledge of and insight into nature was astounding, and this underscored the educational reality of the value of prior learning as a foundation for new knowledge. My learners taught me the value of nurturing positive relationships and experiences, being optimistic, building relationships and valuing honesty and trust. Allison and Ramirez (2020) stated that if we hope to impart learning that empowers children, teachers must be compassionate and emotionally alert. In my classroom, the focus on social and emotional learning encouraged us to reflect on our learning and life experiences.

I recall how I had to learn from my triumphs and failures and come to terms with my flaws. In the same way, it was enthralling to notice how many shy learners unfolded their wings and spread them to fly, whilst the more verbal and outgoing ones learned to accept constructive criticism and allowed others to shine. I found inspiration and felt encouraged by exploring dynamic and creative learning opportunities such as poetry writing, drawing, paragraph writing and listening to music.

Moving forward

I plan to utilise the new insights that I gained. Now, I highly regard the value of listening to children's voices and embrace what I discovered about how they dealt with death, despair, bullying, disability, joy and building friendships. I am eager to kindle my learners' interests and their life experiences, and I would like to encourage transparency in their thoughts and an expansion of their emotional vocabulary and creativity. I look forward to a future when I shall design and use classroom ice breakers that uncover sincere emotions. I shall also endeavour to be more pioneering by working closely with my colleagues to uncover social and emotional learning in the schools where we teach.

I have always striven to utilise teaching methods and approaches that inspire social justice in my classroom. The Department of Education (2008) stated that our colourful South African flag is an example of South Africa's pledge to a non-discriminatory society. The unique design and colours liberate South Africans to make the flag personally meaningful and to celebrate diversity. Inspired by my study, my thoughts are rooted in diversity and inclusive education as an instrument that nurtures teaching and learning in a multicultural environment.

Embarking on a journey of social justice requires the equal participation of all groups in inclusive classrooms where educational endeavours meet everyone's needs. It is my responsibility to emulate role-models such as our former president, Mr Nelson Mandela, so that I shall enkindle a spirit of reconciliation and respect for diversity in my classroom and amongst my colleagues. It is my mission that my learners, now and in the future, will understand what social justice entails and how to achieve it. I shall thus encourage them to accept unequivocally that this is a social responsibility because of our cultural and religious differences. Issues that entail inequality and prejudice need to be handled delicately but assertively as we are all answerable to our public duty and social conscience. In my view, it is essential that we begin to break the chains of social prejudice and boundaries that threaten social justice in classrooms in the junior phase. It is in all classrooms, but in these early year classrooms in particular, that we must instil respect for diversity and find a balance between the well-being of society and the preservation and sustainability of the environment. If our young children accept and embrace these tenets, it will augur well for future generations.

Recommendations

I advise scholars who wish to involve children in research projects to embrace the notion of a content-intensive yet culturally approachable curriculum that entrenches social and emotional learning with the purpose of achieving social justice. Samaras (2002) emphasised that students' upbringing and social and cultural experiences play an imperative role in their development. I endorse this notion as I witnessed the importance of acknowledging and valuing my learners' diverse backgrounds, views and interests.

It is undeniably the role of the teacher to ensure that all the emotions children experience are deemed valid and that their voices are heard. It is critical to safeguard relationships that are not driven by discrimination or any form of prejudice. The classroom must radiate equality and democracy for all. The tenets of social and emotional learning and social justice in education advocate interactive learning that allows all role-players in the classroom to share their stories and reflect on their experiences. Learners should feel free to ask questions, raise their fears and express their hopes. Moreover, it is imperative that all classrooms become safe spaces where children, regardless of their age or background, have a voice and are heard.

Conclusion

The discourse elucidated how important it is that teachers are mindful of children's relationships and emotions. My key learnings were that social and emotional learning and self-study research could anchor explorations of learners' views. Together, my learners and I embarked on a social and emotional self-discovery journey that allowed us to express ourselves liberally. Nevertheless, it was challenging to accommodate all my learners in every aspect of this learning process because embracing one way to express sympathy and love was not enough. I had to get to know my learners personally and acknowledge that each was remarkable and unique. Sadly, I realised that I had not paid enough attention to my learners' social and emotional well-being or emotionally challenging experiences before I commenced this self-study research. I now see that making social and emotional learning a focal point in my teaching allowed them to locate their emotions and thoughts through journal and poetry writing and drawings. These activities encouraged self-awareness and a sense of security.

I also learned to appreciate the significance of the persistent need to build relationships with my learners and colleagues. My critical friends' inputs were invaluable in this regard. I learned that creating and sustaining an optimistic teaching and learning climate inside and outside the classroom is a prerequisite for learning, forging relationships and building character. By encouraging effective and dynamic dialogues, I manged to explore and understand children's voices. This self-study research was thus a portal through which I gained personal self-awareness and emancipation as a teacher. Self-study research involving children can ignite a hopeful mindset, vitalise a sincere attitude to learning and foster social relationships.

The broader significance of this study is that it may encourage positive social change as individuals (particularly teachers of young children) who are informed of its findings may become more understanding, empathetic and supportive of learners' diverse emotional needs. This study endorses a sensitive teaching approach as children have unique needs and encounter trials and tribulations during their lives. This reality compels us to accept that children are vulnerable and that we should thus participate empathetically in emotive conversations and social relationships. It means that we need to be aware not only of children's challenges and emotional/traumatic experiences but also of our own.

I was honoured not only to have the opportunity to value children's voices during my research but also to expose myself to new learnings. The multiple tools for data collection that I used allowed me to step into my learners' world, understand their lived experiences and explore their youthful but insightful perceptions. At the beginning of the study, my learners and I were reluctant to engage at a deep level. Chained by traditional and 'time-honoured' practices and power relations we had built walls around our emotions and tip-toed on invisible boundaries. However, by being expressive and defenceless about my own emotions, I validated their feelings and traumatic experiences. The study opened my eyes to how to reposition my teaching and address social and emotional learning. I also embrace the fact that learners are a valid resource for educational research and development.

The study illuminates how ongoing dialogues with my learners supported my quest for personal and professional development. This self-study research utilising children elicited a sense of belonging and it was a phenomenal experience to be reminded to be genuinely sincere with myself and my learners because we were all learning from one another. It was a captivating experience to be so aware of the dissimilar personalities, social upbringings and diverse emotions that developed inside and outside my classroom.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author has declared that no competing interest exists.

Author's contributions

I declare that I am the sole author of this research article.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the author.

References

Allison, V.A. & Ramirez, L.A., 2020, 'Employing self-study research to confront childhood sexual abuse and its consequences for self, others, and communities', in J. Kitchen, A. Berry, H. Guðjónsdóttir, S. M. Bullock, M. Taylor & A.R. Crowe (eds.), International handbook of self-study of teaching and teacher education, 2nd edn., pp. 1-28, Springer, Singapore.

Bradford, B., 2021, The Doctoral journey: International educationalists' perspectives, Brill, Leiden, viewed 26 May 2021, from http://search.ebscohost.com.ukzn.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=2653214&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

Brandenburg, R. & McDonough, S., 2019, 'Ethics, self-study research methodology and teacher education', in Ethics, self-study research methodology and teacher education, pp. 1-14, Springer, Singapore.

Braun, V. & Clarke, V., 2006, 'Using thematic analysis in psychology', Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [ Links ]

Cohen, J. & Maran, S., 1999, 'Social and emotional learning: A psychoanalytically informed perspective', in J. Cohen (ed.), Educating minds and hearts: Social and emotional learning and the passage into adolescence, pp. 112-123, Teachers College Press, New York, NY.

Collins, C.S. & Cooper, J.E., 2014, 'Emotional intelligence and the qualitative researcher', International Journal of Qualitative Methods 13(1), 88-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691401300134 [ Links ]

Crosby, S.D., Howell, P. & Thomas, S., 2018, 'Social justice education through trauma-informed teaching', Middle School Journal 49(4), 15-23. https://doi.org/10.1080/00940771.2018.1488470 [ Links ]

Denscombe, M., 2010, The good research guide for small-scale social research projects, 4th edn., Open University Press, Berkshire.

Department of Education, 2008, My country South Arica: Celebrating our national symbols and heritage, 2nd edn., Government Printer, Pretoria.

Durlak, J.A., Weissberg, R.P., Dymnicki, A.B., Taylor, R.D. & Schellinger, K.B., 2011, 'The impact of enhancing students' social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school based universal interventions', Childhood Development 82(1), 405-432. [ Links ]

Flewitt, R., 2005, 'Conducting research with young children: Some ethical considerations', Early Child Development and Care 175(6), 553-565. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430500131338 [ Links ]

Furman, R., Coyne, A. & Negi, N.J., 2008, 'An international experience for social work students: Self-reflection through poetry and journal writing exercises', Journal of Teaching in Social Work 28(1-2), 71-85. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841230802178946 [ Links ]

Gerhard, G. & Mayer-Smith, J., 2008, 'Casting a wider net: Deepening scholarship by changing theories', International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching & Learning 2(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2008.020120 [ Links ]

Goleman, D., 1996, Emotional intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ, Bloomsbury, London.

Graham, A., Powell, M.A. & Taylor, N., 2015, 'Ethical research involving children: Encouraging reflexive engagement in research with children and young people', Children & Society 29(5), 331-343. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12089 [ Links ]

Hausfather, S.J., 1996, 'Vygotsky and schooling: Creating a social context for learning', Action in Teacher Education 18(2), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1080/01626620.1996.10462828 [ Links ]

John-Steiner, V. & Mahn, H., 1996, 'Sociocultural approaches to learning and development: A Vygotskian framework', Educational Psychologist 31(3-4), 191-206. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.1996.9653266 [ Links ]

Kelly, P., 2006, 'What is teacher learning? A sociocultural perspective', Oxford Review of Education 32(4), 505-519. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054980600884227 [ Links ]

LaBoskey, V.K., 2004, 'The methodology of self-study and its theoretical underpinnings', in J.J. Loughran, M.L. Hamilton, V.K. LaBoskey & T. Russell (eds.), International handbook of self-study of teaching and teacher education practices, Vol. 1, pp. 817-869, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dorchrecht.

Luthuli, K., Phewa, N. & Pithouse-Morgan, K., 2020, '"Their drawings were eloquent": Learning about drawing as an arts-based self-study method for researching with children', Studying Teacher Education 16(1), 48-65. https://doi.org:10.1080/17425964.2019.1690984 [ Links ]

Masinga, L., 2012, 'Journeys to self-knowledge: Methodological reflections on using memory work in a participatory study of teachers as sexuality educators', Journal of Education 54, 121-137. [ Links ]

McMurtry, A., 2015, Liked your textbook … but I'll never use it in the courses I teach, Teachers' College Record, ID Number 18058, viewed 11 June 2021, from http://www.tcrecord.org/ContentID=18058.

Mkhize, N.S., 2016, 'Integrating cultural inclusivity in a Grade 4 classroom: A teacher's self-study', Unpublished M.Ed. dissertation, University of KwaZulu-Natal, viewed 11 June 2021, from http://researchspace.ukzn.ac.za/handle/10413/14891. [ Links ]

Mkhize, N.S., 2020, 'Exploring social and emotional learning in a Grade 4 classroom: A teacher' self-study', Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of KwaZulu-Natal. [ Links ]

Moskal, M., 2017, 'Visual methods in research with migrant and refugee children and young people', in P. Liam-Puttong (ed.), Handbook of research methods in health social sciences, pp. 1-16, Springer Nature, Singapore.

Newberry, M., 2013, 'Reconsidering differential behaviours: Reflection and teacher judgment when forming classroom relationships', Teacher Development 17(2), 195-213. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2012.753946 [ Links ]

Nkopodi, N. & Mosimege, M., 2009, 'Incorporating the indigenous game of "morabaraba" in the learning of mathematics', South African Journal of Education 29(3), 377-392. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v29n3a273 [ Links ]

Northfield, S. & Sherman, A., 2004, 'Acceptance and community building in schools through increased dialogue and discussion', Children & Society 18(4), 291-298. https://doi.org/10.1002/chi.788 [ Links ]

Panayiotou, M., Humphrey, N. & Wigelsworth, M., 2019, 'An empirical basis for linking social and emotional learning to academic performance', Contemporary Educational Psychology 56, 193-204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2019.01.009 [ Links ]

Pithouse, K., Mitchell, C. & Weber, S., 2009, 'Self-study in teaching and teacher development: A call to action', Educational Action Research 17(1), 43-62. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650790802667444 [ Links ]

Pithouse-Morgan, K., Deer-Standup, S.O. & Ndaleni, T., 2019, 'Stories blending, flowing out: Connecting teacher professional learning, remembering, and storytelling', in K. Pithouse-Morgan, D. Pillay & C. Mitchell (eds.), Memory mosaics: Researching teacher professional learning through artful memory-work, pp. 155-173, Springer, Cham.

Pithouse-Morgan, K. & Samaras, A.P., 2020, 'Methodological inventiveness in writing about self-study research: Inventiveness in service', in J. Kitchen, A. Berry, S.M. Bullock, A.R. Crowe, M. Taylor, H. Guðjónsdóttir et al., (eds.), 2nd International handbook of self-study of teaching and teacher education, pp. 427-460, Springer, Singapore.

Samaras, A.P., 2002, Self-study for teacher educators: Crafting a pedagogy for educational change, Peter Lang, New York, NY.

Samaras, A.P., 2011, Self-study teacher research: Improving your practice through collaborative inquiry, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Samaras, A.P. & Freese, A.R., 2006, Self-study of teaching practices primer, Peter Lang, New York, NY.

Shabani, K., 2016, 'Applications of Vygotsky's sociocultural approach for teachers' professional development', Cogent Education 3(1), 1252177. [ Links ]

Swartz, M.K., 2017, 'Social and emotional learning', Journal of Pediatric Health Care 31(5), 521-522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2017.06.001 [ Links ]

Taylor, H.E. & Larson, S., 1999, 'Social and emotional learning in middle school', The Clearing House Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues, and Ideas 72(6), 331-336. https://doi.org/10.1080/00098659909599420 [ Links ]

Taylor, L.P., Newberry, M. & Clark, S.K., 2020, 'Patterns and progression of emotional experiences and regulation in the classroom', Teaching and Teacher Education 93, 103081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2020.103081 [ Links ]

Vygotsky, L.S., 1978, 'Sociocultural theory', Mind in Society 6, 52-58. [ Links ]

Wiseman, A.M., 2010, '"Now I believe if I write I can do anything": Using poetry to create opportunities for engagement and learning in the language arts classroom', Journal of Language and Literacy Education 6(2), 22-33. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Ntokozo Mkhize-Mthembu

MkhizeN39@ukzn.ac.za

Received: 22 June 2021

Accepted: 10 Nov. 2021

Published: 29 Mar. 2022

1 . Pseudonyms are used to refer to the learners.