Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Childhood Education

versão On-line ISSN 2223-7682

versão impressa ISSN 2223-7674

SAJCE vol.10 no.1 Johannesburg 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v10i1.738

REVIEW ARTICLE

Expanding vocabulary and sight word growth through guided play in a pre-primary classroom

Annaly M. StraussI; Keshni BipathII

IFaculty of Education, International University of Management, Windhoek, Namibia

IIDepartment of Early Childhood Development, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: This article is based on a study that aimed at finding out how pre-primary teachers integrate directed play into literacy teaching and learning. Play is a platform through which young children acquire language

AIM: This study uses an action research approach to understand how guided play benefits incidental reading and expands vocabulary growth in a Chinese Grade K classroom

METHOD: Data collection involved classroom observations, document analysis, informal and focus group discussions

RESULTS: The results revealed the key benefits of play-based learning for sight word or incidental reading and vocabulary development. These are: (1) teacher oral and written language learning, (2) learners' classroom engagement is promoted, (3) learners were actively engaged in learning of orthographic features of words, (4) learners practised recognising the visual or grapho-phonemic structure of words, (5) teacher paced teaching and (6) teacher assesses miscues and (7) keep record of word recognition skills

CONCLUSION: In the light of the evidence, it is recommended that the English Second Language (ESL) curriculum for pre-service teachers integrate curricular objectives that promote practising playful learning strategies to prepare teachers for practice

Keywords: guided play; cognitive development; literacy; sight word learning; explicit teaching.

Introduction

This article examines the use of directed play as a teaching and learning strategy during English Second Language (ESL) lessons in a Chinese Grade K classroom. Using a play-based strategy for teaching sight words may expand vocabulary. Play is an important vehicle for promoting language learning during early childhood and a developmentally appropriate way of teaching a range of skills and knowledge (NAEYC 2013). Playful learning refers to free play, whereas guided play is child-directed. Guided play also refers to learning experiences that combine the child-directed nature of free play with a focus on learning outcomes and adult mentorship. Guided play offers an exemplary pedagogy because it respects children's autonomy and their pride in discovery (Weisberg et al. 2016).

According to Copple and Bredekamp (eds. 2009:14), 'play is an important vehicle for developing self-regulation and for promoting language, cognition and social competence'. When young children do not gain an understanding and knowledge of the alphabet and its sound structure, the child will not be able to make connections to speak, read or write. Brown (2014:36) stated that 'learning to read is a developmental process'. According to the National Institute of Childhood Development, early reading skills can be grouped into categories with three elements: phonemic awareness, knowledge of high-frequency sight words and the ability to decode words.

Letter names and letter sounds could be taught concurrently within an early literacy lesson. Letter name knowledge is defined as the ability to recognise and identify the letters of the alphabet, whereas letter-sound knowledge refers to the ability to recognise and pronounce the sounds that represent each letter of the alphabet (Mann & Foy 2003). For this article, sight words refer to automatic reading of high-frequency words. The article emphasises the role that the teacher can play in making play-based teaching and learning a developmental and education experience in second language classrooms.

In a comparison of Chinese and Namibian early literacy teaching and learning, the following features were prominent: (1) Chinese teachers have a monoculture, whereas the language culture of Namibian teachers in pre-primary learning communities differ from that of the learner and (2) basic education in China includes 3 years of compulsory preschool education (3-6 years), whereas Namibia has 1 year of preschool education (5-6 years) for those who can afford the service. Therefore, many learners may not benefit from language learning within these culturally vast and linguistically diverse environments of Namibia (Strauss & Bipath 2018). When pre-primary learners do not understand their teachers who speak a different native tongue, they may lose out on potential language learning. Unlike teaching and learning within a Namibian early childhood context, Chinese foreign language learning environments allow young children to gain meaningful language skills. Within these language learning environments, teachers provide environment-rich materials and experiences to encourage learners to explore the environment and their ideas through play (Epstein 2014). In a study, Frolland et al. (2013); Hood, Conlon & Andrews (2008) stated that home literacy teaching experiences are more important in developing emerging literacy skills. In the absence of these experiences, well-trained pre-primary teachers may provide literacy-rich experiences to affect children's language growth and learning positively. When teacher training prepares pre-service teachers to implement explicit play-based teaching and learning strategies it can bridge the gap that often exists between 'teachers' teaching beliefs and their classroom practices' (Strauss 2018:148).

Research argues that play and language learning go hand in hand (Zigler & Bishop-Josef 2009). Depriving children of play denies them vital opportunities to practice important cognitive and social skills that develop their imagination and creativity (Christie & Roskos 2000; Hirsh-Pasek et al. 2008; Pellegrini 2009). Pre-primary classroom contexts influence play activities and language learning for young children. To be particular, classroom environment and space arrangements are two key elements to enhance young children's play within the classroom context (Heidemann & Hewitt 2010). In highly structured didactic and overcrowded early childhood classrooms the role of play, and thus language learning is at risk. Overcrowded pre-primary classes, lack of resources and untrained early childhood teachers hamper children's possibilities to benefit from language learning. There is a need for pre-service teacher training in Namibia to explore play-based teaching and language-learning strategies that can advance teachers' classroom performance under such circumstances. Teacher training provides a terrain to expand the pre-service teachers' curriculum that may strengthen teaching and learning in practice. The question of this study is: How do teachers integrate play during literacy teaching to expand sight word and vocabulary growth in pre-primary classrooms?

Definition of play

Danniels and Pyle (2018) defined play as 'an enjoyable', intrinsically motivated behaviour that is non-rule-governed, non-goal-oriented and 'just pretend'. Play-based learning results from the active engagement of a child or the interaction between the child and peers and the environment. Young children need safe spaces for social interaction to promote play-based language learning. Genishi and Dyson (2009:61) indicated that 'play is a socially complex and communicative act'. These authors highlight the benefit of play and reveal that 'young children learn from their teachers about symbols and their use to take action in childhood worlds' (p. 82). On the other hand, Hughes (2010) argued that there is not a clear definition of play. Play is both play and work. Play allows children to manipulate objects, follow prompts, and apply their minds to create new worlds. Goodman (1994) cited by Hughes (2010:8) revealed that 'it is at the midpoint between play and work that the best teaching occurs'. Adults design the setting to highlight a learning goal whilst ensuring that children have the autonomy to explore within that setting. Autonomy allows young children the freedom to take initiative, be persistent and creative whilst gaining language skills during guided play. Copple and Bredekamp (eds. 2009) stated that early childhood professionals who employ a literacy engaging atmosphere where developmentally appropriate practices are used prove to have thriving and successful learners.

Theoretical underpinnings of play

Research shows that play facilitates intellectual growth. Bruner (1985) and Sutton-Smith (1967) maintained that play provides a comfortable and relaxed atmosphere in which children can learn to solve a variety of real-world problems, which may be of great benefit to them. Vygotsky (1978) argued that there are several acquired and shared tools that aid in human thinking and behaviour - tools that allow for clear thinking and understanding within a specific context such as teaching guided play. These tools are provided during formal instruction, and the role of parents and teachers is critical in transmitting their knowledge and beliefs to children (Maratsos 2007). Vygotsky (1978:102) further postulated that 'to play together, children construct imaginary situations in which meanings and perceptions have a "mediated" relationship'. Bruner's (1985) theory aligned with Vygotsky's (1978) sociocultural theory in terms of the zone of proximal development (ZPD), scaffolding and learning within a social community. Play provides this social community and serves as a vehicle to advance language and literacy development. The ZPD refers to the distance between children's 'actual' and 'potential' levels of development (Vygotsky 1978). When children independently solve problems, they function at the 'actual' level of development. Justice and Ezell (2001) indicated that some children may identify all alphabet letters, whereas others know very few concepts about print (e.g. alphabet knowledge, the directionality of print, the concept of word), whereas others know a great deal. Thus, the focus of teaching within the ZPD or effectively 'scaffolding children's understanding' is centred on allocating tasks that children cannot yet accomplish on their own, but that they can accomplish within the ZPD (Vygotsky 1978).

Language and literacy development

Hughes (2010:74) indicated that 'children are beginning to represent reality to themselves through symbols to let one thing stands for another'. When children start using a language they point to objects and people using words to name reality. Hughes (2010) termed this action 'symbolic play'. Symbolic or make-believe requires the ability to use symbols (McCune 1995 cited by Hughes 2010) and prepares young children for school literacy. Social experiences acquired through play lay the foundation for later reading and writing (DeZutter 2007 cited by Hughes 2010). When teacher training prepares pre-service teachers to use a variety of teaching and learning strategies for practice, children from diverse economic and language backgrounds may thrive in their language learning.

Literacy-rich environment

One of the characteristics of a high-quality classroom is that it exhibits an appropriate language-rich environment (Howes et al. 2008; Pianta et al. 2008; Thomason & La Paro 2009). Children who attend quality pre-kindergarten and pre-primary facilities know more letters, more letter-sound associations and are more familiar with words and book concepts than their peers who do not attend such a programme (Barnett, Larny & Jung 2005). As the classroom's physical environment provides the foundation for literacy learning (Morrow, Tracey & Del Nero 2011), teachers must provide the appropriate environment and materials that emphasise the importance of speaking, reading and writing. Providing space and props that focus on literacy that invites exploration, discovery and stimulates behaviours in which children and teachers are more engaged in teaching and learning activities for longer periods.

The term 'sight word' denotes to any word read automatically. High-frequency words are also known as sight words and learners should be able to read the words automatically and fluently (Brown 2014). Sight words refer to high-frequency irregularly spelt words, presumed to be impervious to decoding (Murray et al. 2019). Recognising words incidentally is important during early literacy development. Sight words stimulate learners' experiences and background so that meaning can be constructed from print. Print referencing occurs when an adult uses both verbal and non-verbal cues to guide an early reader's attention to language elements in the text. Johns and Wilke (2018) revealed that the beginning reader must learn at least 13 words at sight. These 13 words are a, and, for, he, in,is, it, of, that, the, to, was and you. Repeated exposure to sight words or matching pictures to text allows children to recognise orthographic patterns in words and as a result improve their sight vocabulary. According to Ehri (2014), orthographic mapping (OM) involves the formation of letter-sound connections to bond spelling, pronunciation and meaning of specific words in memory. Orthographic mapping is enabled by phonemic awareness and grapheme-phoneme knowledge. Orthographic mapping supports sight word reading and facilitates beginners to learn articulatory features of phonemes and grapheme-phoneme relations when letter-embedded picture mnemonics are taught. It explains how young children learn to read words by sight, spell words from memory and to acquire vocabulary words from print. Print experiences become helpful during individual reading when learners point to and track words in the text. Words should be meaningful and of interest to children to have a better understanding of the new words and what they mean for them (Johns & Wilke 2018 cited Hans et al. 2005). According to Justice and Ezell (2004), print experiences could serve as explicit techniques when making comments or providing explanations about concepts of print and the use of elaborative questions. Young readers who master sight words by late childhood will become efficient and effective readers (Johns & Wilke 2018).

The role of the teacher

It is the teacher's responsibility to set up the environment not by just adding words or labels, but adding meaningful print so that children can communicate and learn new information and concepts (Heroman & Jones 2010). The intentional teacher continually assesses each child's progress and adjusts his or her strategies to meet the child's individual needs (eds. Copple & Bredekamp 2009; Epstein 2014). In working with the teachers, Jones and Reynolds (2011) identified seven roles that teachers take on in children's play. These consist of the teacher as a 'stage manager, mediator, player, scribe, assessor, communicator and planner, observer and recorder' (Jones & Reynolds 2011).

The 'stage manager' is the role teachers take when setting up the classroom environment to include props and materials and allow time for children to play. The role of 'mediator' is when the teacher works with children to help them solve conflicts, teaching them problem-solving skills (Jones & Reynolds 2011). The teacher in the role of 'player', sustains play as the teacher participates in the children's play (Jones & Reynolds 2011). As a 'scribe', 'recorder' and 'observer' the teacher to identify the children's experiences as they play can find ways to support and enhance children's play (Jones & Reynolds 2011). As an 'assessor' and 'communicator' the teacher identifies what can be done to support children in the learning process (Jones & Reynolds 2011).

In the role of 'player', the teacher may inhibit children's learning by interrupting the play or directing it (Jones & Reynolds 2011). Encouraging teachers to plan for children's learning through play is not easily accepted, therefore, the role of 'assessor' and 'communicator' becomes necessary so that teachers can see how children learn as they played (Jones & Reynolds 2011).

^rND^1A01^nSharon^sMcAuliffe^rND^1A01^nCosmas^sTambara^rND^1A02^nEmine^sSimsek^rND^1A01^nSharon^sMcAuliffe^rND^1A01^nCosmas^sTambara^rND^1A02^nEmine^sSimsek^rND^1A01^nSharon^sMcAuliffe^rND^1A01^nCosmas^sTambara^rND^1A02^nEmine^sSimsekORIGINAL RESEARCH

Young students' understanding of mathematical equivalence across different schools in South Africa

Sharon McAuliffeI; Cosmas TambaraI; Emine SimsekII

IFaculty of Education, Cape Peninsula University of Technology, Cape Town, South Africa

IICentre for Mathematical Cognition, Loughborough University, Loughborough, United Kingdom

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Mathematical equivalence is a critical element of arithmetic understanding and a key component of algebraic thinking which is necessary for success in all levels of mathematics. Research studies continue to highlight misconceptions related to equivalence and reveal that many primary school students have a narrow and limiting view of the equals sign as an operation

AIM: This study aims to investigate young students' understanding of mathematical equivalence in South Africa with a particular focus on their interpretations of the equals sign

SETTING: Research data was obtained from students across six schools from different contexts within the Western Cape

METHODS: We gave students an adapted standardised assessment containing 15 items related to equivalence

RESULTS: Our analyses indicated that students focus more on the equals sign as an operation which involves calculating an answer. While some referred to equivalence as meaning the same as, most of them were inclined to accept the operational definition of the equals sign (i.e. the answer to the problem) as a better and preferred definition. In addition, student performance was poor on equation-solving problems and they rarely used comparative relational strategies in their solutions

CONCLUSION: The findings of this research confirmed that difficulties with equivalence reported by earlier research is widespread across this group of grade 4 students. This has implications for both curriculum, textbook and materials design and teacher professional development

Keywords: Mathematical equivalence; The equals sign; Early algebra; Operational view; Relational view.

Introduction

Equivalence is a foundational concept for algebraic thinking and is necessary for success at all levels of mathematics. Research studies reveal that many primary school students have a narrow view1 of the equals sign as an operation and difficulty solving equivalence problems. The concept of equivalence is a well-recognised challenge for many students, and there is evidence to suggest that difficulties with equivalence are linked to inappropriate generalisation of knowledge constructed from overly narrow experience with arithmetic (McNeil 2014; McNeil & Alibali 2005).

This study looked at grade 4 students' understanding of mathematical equivalence across different schools in South Africa. This is important given the links between the concept of equality and future development of algebraic ideas (Alibali et al. 2007; Carpenter, Franke & Levi 2003). Grade 4 was selected to better understand what students had learned from their exposure to equivalence in the Foundation Phase (age 6-9 years) and how it is manifested at this level. Another reason for the selection of a specific school-year group was because a similar study (McNeil 2007) showed that operational view was most entrenched around age 9 across (American) elementary school students. We aim to investigate whether difficulties understanding equivalence are also prevalent in South African primary students at this specific age and grade. We also aim to compare our results with those from similar international studies to gain a better understanding of what is needed in the teaching of equivalence. We believe this research will help us to determine what content focus is needed to teach equivalence in schools, given there is a strong argument in South Africa for better mathematical support in the early grades.

Literature review

Key concepts regarding students' views of the equals sign

Mathematical equivalence is a relation which is reflexive, symmetrical, and transitive (Jourdain 1912, cited in Asghari 2019). The reflexive property of equality states that a number is always equal to itself, transitivity means that if a = b and b = c then a = c, and symmetry means that a = b is identical to b = a. Mathematics education researchers describe mathematical equivalence as the relationship between two quantities which are the same and interchangeable (e.g. 2 + 3 = 1 + 4) (McNeil 2014). Essien and Setati (2006) concur that the equals sign is used to indicate the relationship between quantities or values in mathematics. Earlier research has shown that primary school students have different interpretations of the equals sign. Some view the equals sign as an operation and interpret it as an arithmetic computation. Such a view is called an operational view of the equals sign (Kieran 1981; Knuth et al. 2006). However, the formal understanding of mathematical equivalence involves seeing the equals sign as a relational symbol that has both sameness and substitutive components (Carpenter et al. 2003; Jones et al. 2012; Kieran 1981). This means that students should be able to recognise the equals sign 'as same as' and also as meaning 'can be substituted for' (e.g. 31 + 40 = 30 + 1 + 40 and so 30 + 1 + 40 = 31 + 40). Such views of the equals sign are called relational views of the equals sign. Relational views thus constitute two aspects: sameness and substitution.

As discussed above, the equals sign has a variety of meaning and purpose which can be confusing for students, and its meaning is highly dependent on the nature of the task and the tools available (Essien & Setati 2006; Jones & Pratt 2005). However, there are some studies which suggest that students who view the equals sign as an operational symbol perform poorly in algebra compared with those who hold a relational view of the equals sign (Hattikudur & Alibali 2010; Knuth et al. 2006). There is also evidence to suggest that viewing the equals sign relationally and flexibly, which correlates with arithmetic competence, can assist with mastery of algebra and other mathematical concepts in the higher grades (Matthews et al. 2012). Thus, we conclude that although viewing the equals sign operationally can help students solve some arithmetic problems (especially traditional arithmetic problems in operations-equals-answer form, a + b = c), students need to hold a relational view of the equals sign to solve more complex equations (for example non-traditional equations different than equations in operations-equals-answer form, such as a = a, a = b + c, a + b = c + d) and for future algebra learning (see McNeil et al. 2016).

The change-resistance account and students' difficulties with mathematical equivalence

Previously, students' difficulties with equivalence have been attributed to their immature cognitive skills and logical structures, low working memory capacity and lack of proficiency with basic number facts (Kaye 1986; Kieran 1981; McNeil 2014). However, McNeil and Alibali (2005) argued that the early learning environment could hinder students' understanding of mathematical equivalence. Based on this, they formulated the change-resistance account. This theory claims that students detect and extract (often subconsciously and incidentally) patterns which they encounter regularly in traditional arithmetic computation. These patterns are called operational patterns. McNeil and Alibali (2005) highlight three operational patterns that students develop through over-practising traditional equations (i.e. a + b = c): (1) students think that all operations should be on the left side of the equals sign, (2) operations should be followed by the equals sign and then by a blank for the unknown and (3) all given operations on all given numbers must be used as the equals sign means to 'do something' (McNeil & Alibali 2005).

Although some of these operational patterns can help students solve traditional arithmetic problems, these representations become entrenched and students begin to rely on them as their default representations when they encounter novel mathematics problems later (Machaba & Makgakga 2016; McNeil & Alibali 2005). Moreover, students fail to highlight the interchangeable nature of the two sides of an equation (McNeil et al. 2006; Seo & Ginsburg 2003). All these imply that too much exposure to traditional equations in the early years of schooling can impact students' future understanding of mathematical equivalence. McNeil and Alibali (2005) contended that in the United States, students learn arithmetic in a procedural fashion for years before they learn to reason relationally about equations. Li et al. (2008) argued that students are seldom challenged in their interpretation of the meaning of the equals symbol in the primary school.

There is evidence showing that students in some countries have better understanding of mathematical equivalence than their peers of the same age in other countries (Capraro et al. 2007, Capraro et al. 2010; Jones et al. 2012). Some other studies within the United States showed that practising non-traditional equations and having conceptual instruction (e.g. emphasis on relational interpretation of the equals sign, using the equals sign in different contexts including symbolic and non-symbolic contexts) can improve understanding of mathematical equivalence in some students (e.g. Baroody & Ginsburg 1983; Jacobs et al. 2007). These findings support the change-resistance account and suggest that given the right circumstances, young students can understand mathematical equivalence. Thus, students should be encouraged to solve various non-traditional equations in different formats, and classroom instruction should support the relational meaning of the equal sign which include sameness and substitution components.

Students' understanding of mathematical equivalence in South Africa

Many studies conducted in Western countries reveal that students understand the equals sign not as relational, but rather as operational, requiring them to 'work out the answer' (Baroody & Ginsburg 1983; Knuth et al. 2006). There are some studies which show that South African students also have difficulties with viewing the equals sign as a relational symbol and understanding mathematical equivalence. For example, the study by Essien and Setati (2006) explored grades 8 and 9 students' interpretations of the equals sign in the South African context and found that grades 8 and 9 students viewed the equals sign as a tool to compute the answer rather than a relational symbol to compare the quantities. Machaba and Makgakga (2016) revealed that grade 9 students in one participating school interpreted the equals sign as a 'do something' and unidirectional (one-sided) sign, not as the concept that represents an equivalent (concept of keeping both sides of the equals sign equal) of two quantities. Results from the Vermeulen and Meyer (2017) study of grade 5 and 6 students' understanding of equivalence indicated that few students had a well-developed relational understanding of the equals sign and many could not describe the meaning of the equals sign correctly. Machaba and Makgakga (2016) attributed misinterpretation of the equals sign to how students had been taught the concept of equivalence at lower grades, where greater emphasis was placed on rules rather than the meaning of a concept. Essien (2009) argued similarly in his study of the introduction of the equals sign in grade 1 textbooks. He claimed the textbook examples introduced the equals sign within the context of addition and subtraction entrenching the 'understanding of the equals sign as an operational rather than symbolic symbol' (Essien 2009:29). The notion of equivalence was embedded in the operations, making it difficult for students to develop a relational understanding of the concept. He also highlighted the lack of emphasis of equivalence in Foundation Phase curriculum documents which is also true of the current Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (Department of Basic Education 2011) and has implications for teaching and learning.

How to assess students' understanding of mathematical equivalence: A theoretical framework

There have been many studies over the past 35 years looking at students' understanding of equivalence. The Mathematical Equivalence Knowledge Construct Map designed by Rittle-Johnson et al. (2011:3) provides a 'representation of the continuum of equivalence knowledge' broken into different levels. In this map, there are four continuous levels. Each level describes what students are likely to do at that level, such as how they perform on specific types of equations and how they interpret the equals sign (see Table 1). However, these levels should not be interpreted as discrete because the literature has shown that students may develop different interpretations of the equals sign synchronously (e.g. Jones et al. 2012), or their equation-solving performance might also depend on the other features of the problems rather than traditional versus non-traditional equations dichotomy (e.g. Hornburg, Wang & McNeil 2018). Matthews et al. (2012) used this Construct Map to develop a valid and reliable assessment to measure students' understanding of equivalence. The researchers developed the Mathematical Equivalence Assessment (MEA) and this has been frequently used in research focusing on students' understanding of equivalence (e.g. Fyfe et al. 2018). Not only does the Construct Map depict how most of students develop a sophisticated understanding of mathematical equivalence, but it also provides a useful basis for researchers who desire to develop instruments to reliably measure students' understanding of equivalence.

We used this Construct Map for the adaptation of the MEA to our study to use the MEA with South African students aged 9-10 years old. We sampled items from different levels of the Construct Map to be able to provide a comprehensive picture regarding a group of South African grade 4 students' understanding of mathematical equivalence in six schools in the Western Cape.

The present study

Despite the vast literature investigating students' understanding of mathematical equivalence in Western countries in early grades of primary schooling, whether students' difficulties with equivalence, reported in the literature, are common in South African context has been unclear. To fill this gap in the literature, this study examined grade 4 students' understanding of mathematical equivalence in South Africa with a particular focus on their interpretations of the equals sign. Through this study, we also aimed to compare our findings from a sample of grade 4 students with the findings of three other studies conducted with grade 5 and 6 as well as grade 8 and 9 South African students (Essien & Setati 2006; Machaba & Makgakga 2016; Vermeulen & Meyer 2017) to see if the same pattern of results of students' understanding of mathematical equivalence occurs.

Method

Participants

A total of 410 grade 4 primary school students, from six different primary schools across the Western Cape, volunteered to participate in the study. The schools are classified quintiles 4 and 5 which means that they are fee paying schools and all have English as their language of learning and teaching (LoLT) from grade 1. Two of the schools have a mixture of students with either Afrikaans or isiXhosa as their home language. The test was administered in the middle of the grade 4 academic year and nine of the students from the group were excluded from the analyses, as there were more than 1/3 of the assessment items unanswered. This left us with 401 students (Mage = 9.91, SD = 0.61, ranging from 9 to 12). This is the largest sample of grade 4 students that have been tested for understanding of equivalence in South Africa to date, as far as we are aware.

All students gave written consent to participate in the study, and parent consents were obtained. The mathematics teacher of each class and the head teacher were informed about the purpose and procedure of this research.

Materials and procedure

The students were given a paper-and-pencil assessment to complete within their usual lesson time, under test conditions. We used the MEA developed by Rittle-Johnson et al. (2011) and Matthews et al. (2012) in this study. The MEA was formed with 27 items involving three types of items: (1) open-ended equation-solving items, (2) True/False equation-structure items and (3) definition items. These items were developed to assess students' interpretations of the equals sign, how they perform on different types of equations and whether they use shortcuts to solve equivalence problems.

We made a few adaptations to the original assessment. There were a few reasons for that: (1) we expected grade 4 students to have higher abilities than past international samples, which also include grade 2 and grade 3 students, (2) we used a shorter version of the original assessment for practicality, (3) we increased the difficulty of items by increasing the size of numbers in some questions to make them suitable for our sample (e.g. instead of 7 + 6 = 6 + 6 + 1, we used 70 + 60 = 60 + 60 + 10), (4) we used the substitution definition of the equals sign in one of the questions (i.e. the equals sign means 'the two sides can be swapped') (similar to Jones et al. 2012), and (5) were placed letters, used as unknowns, in the questions with boxes given that some students might not have been taught letters as unknowns. Finally, we should note here that there was another difference in the equation-solving items between the original MEA and the adapted version of the MEA that we used in the present study. In the original assessment, Matthews et al. (2012) encouraged students to find a shortcut to solve problems by stating that 'You can try to find a shortcut so you don't have to do all the adding'. We did not ask students to use shortcuts as we were interested in students' spontaneous use of solution strategies. We asked students to show their working for all equation-solving problems.

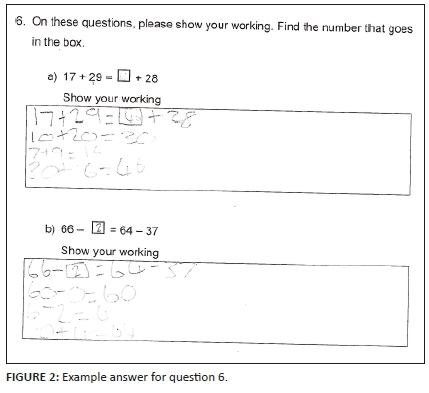

The assessment instrument used in the present study consisted of 15 items: 4 True/False equation-structure, 6 definition and 5 equation-solving items. Figure 1 depicts examples from the final form of the student assessment for each question type. Through the equation-structure items, we measured whether students were able to judge correctness of an equivalence statement, and which non-traditional equations they did not accept. Definition items assessed students' interpretations of the equals sign. Finally, equation-solving items measured students' performance on non-traditional equivalence problems and whether they exploited comparative relational strategies (see Table 1 for the definition of comparative relational strategies) to solve these questions.

The assessment was completed by students on a whole-class basis, within their usual lesson time, under test conditions, and was administered by their regular classroom teachers. To ensure that assessment administration was identical across the schools, we provided detailed information to the teachers in relation to testing procedure.

Coding

We used two different scoring schemes to code students' responses to the assessment items. Firstly, students' responses to the items were scored for correctness irrespective of the solution method (i.e. 1 for a correct answer and 0 for an incorrect answer). We marked blank items as incorrect unless a participant left more than one third of the assessment blank (more than 5 items). In that case, we excluded the participant altogether as mentioned previously. In the second scoring scheme, for five open-ended equation-solving items, the students received a point if they mentioned the equality relation between values on the two sides of the equation. In other terms, students received a point if they use a 'comparative relational strategy' (e.g. 17 + 29 = _ + 28, if students mention that the answer is 18 because 28 is 1 smaller than 29, so the answer should be one larger than 17). We call these strategies relational strategies hereinafter. According to the Construct Map, the use of relational strategies shows that students move to the final and fourth level in their development of equivalence knowledge.

We excluded one of the definition items (item 4b) from the analyses because of this item being used as a distractor (see Jones et al. 2012). The performance of the instrument and coding activity for the rest of the items was checked by estimating internal consistencies. Cronbach's alpha was 0.715 for all of 14 items for whole sample when the items were scored as correct/incorrect. Cronbach's alpha was 0.746 for five relational codes for five equation-solving items. These Cronbach's alpha values are acceptable. We checked the factor structure of the assessment using Mplus 8.1 software, and found that three-factor model had the best-fit indices (similar to Fyfe et al. 2018; Matthews et al. 2012). The 14 assessment items loaded positively onto their relevant factors that were definition, equation-structure and equation-solving.

Ethical considerations

Approval to conduct this study was received from the Education Faculty Ethics Committee, Ethical Clearance number: EFEC 6-8/2018, 19 August 2018.

Results

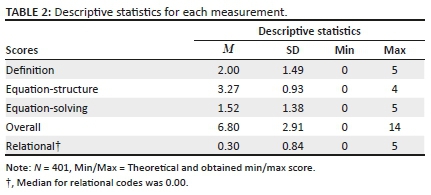

Descriptive statistics

We first calculated definition, equation-solving and equation-structure scores for each student, based on students' accuracy on each item type. We then calculated an overall score for each student based on these three scores. Next, we calculated a relational score for each student, based on our relational codes. Table 2 depicts the descriptive statistics regarding these scores. The results demonstrate that there was good variance in performance on each sub-scale and overall assessment except for use of relational strategies. The mean score for relational showed that students rarely used relational strategies.

Student performance

Students' definitions of the equals sign: We asked the students to rate the different definitions of the equals sign. Sixty-six per cent of whole sample rated the sameness definition (i.e. the equals sign means the same as) as good, and 36% of whole sample rated the substitution definition (i.e. the equals sign means the two sides can be swapped) as good. As expected, the number of students who endorsed the substitution definition of the equals sign was lower than those who endorsed the sameness definition. Moreover, 82% of the students who endorsed the substitution definition already rated the sameness definition as good.

In terms of the operational definition, 84% of whole sample rated 'the equals sign means the answer to the problem' as good. This shows that most of the students viewed the equals sign operationally. Moreover, 26% (n = 103) of the whole sample did endorse neither the sameness nor the relational definition but endorse only the operational definition, whereas 58% (n = 233) of whole sample endorsed at least one of the relational definitions together with the operational definition. This implies that just above one fourth of the students viewed the equals sign only as an operational symbol.

Three hundred and sixty-one students made a valid decision about the best definition amongst the provided definitions. Fifty-nine per cent of these students chose 'the answer to the question' as the best, 29% of them chose 'the same as' as the best, and 12% of them chose the substitution definition as the best definition. According to this, most of the students were inclined to think that the operational definition best explains the meaning of the equals sign, and less than half of the students recognised relational definition of equals sign as the best definition.

In terms of generating a definition, only 44% of the participating students provided a relational definition of the equals sign (e.g. such as 'the same as', 'equal to', and 'equivalent to') to at least one of the following two questions 'What does the equals sign '=' mean? Does it mean anything else?' This is consistent with the results above that 41% of the students chose one of the relational definitions of the equals sign as the best definition. Choosing and generating a relational definition of the equals sign appear to be necessary to move to Level 3 and further on the Construct Map.

Equation-structure and equation-solving performance, and relational strategy use: We found that 99% of whole sample answered at least one of four equation-structure questions correctly, and 53% of those answered all four questions correctly. These findings illustrate that the students performed successfully on equation-structure problems. This suggested that most of the students fulfilled one of the requirements of level 3 of the Construct Map, which is evaluating successfully mathematical sentences in non-traditional format.

Unlike their high scores on equation-structure items, students performed poorly on equation-solving items. Twenty-nine per cent of whole sample did not answer any of five items correctly, 28% answered only one item correctly, and only 2% of whole sample answered all equation-solving questions correctly. Many of the answers showed that students held an operational view of the equals sign as they interpreted the equals sign as an operation to 'work out an answer' (see Figure 2).

When considering relational strategy use, there seemed to be little variance in the scores as the students rarely used relational strategies. Eighty-four per cent of the participating students never used a relational strategy. Relational-strategy use is necessary for the Levels 3 and 4 of the Construct Map. Thus, for these questions, these students currently did not show the knowledge to move them to Level 3 or 4 of the Construct Map.

Discussion

The findings of the present study shed some light on what understanding of equivalence South African grade 4 students have. This is the first study investigating the equivalence concept with a sample of grade 4 students in South Africa as opposed to other studies with older students (Essien & Setati 2006; Machaba & Makgakga 2016; Vermeulen & Meyer 2017). First, we found that the students were inclined to think operationally in terms of defining equivalence. Although they performed better on equation-structure items, they performed poorly on equation-solving items and provided little to no relational strategies when solving equivalence problems.

We found that most of the students tended to think of the equals sign as an operational symbol, indicating that an answer should be followed after this symbol. Evidence for this came from our three findings: (1) most of the students rated 'the equals sign means the answer to the problem' definition as good, (2) just above half of them chose this definition as the best definition amongst the others and (3) nearly half of the students were not able to provide a relational definition when they were asked to define the equals sign. It can be concluded that the South African students researched in this study interpreted the equals sign operationally, and this is consistent with what other studies found with students at similar ages across different countries (Capraro et al. 2010; Fyfe et al. 2018; Jones et al. 2012; Knuth et al. 2006; Molina & Ambrose 2008; Powell & Fuchs 2010). In terms of development of equivalence knowledge based on the Construct Map of Rittle-Johnson et al. (2011), most of the students lacked the necessary knowledge (i.e. recognising and generating a relational definition of the equals sign) to be able to move to level 3 and level 4 of this map. On the contrary, we found that just above half of the students endorsed sameness and/or substitution definitions while they also endorsed the operational definition (answer to the problem). This provided further evidence to suggest that students may hold different views of the equals sign simultaneously (Lee & Pang 2020) and the levels at the Construct Map should not be interpreted as discrete stages.

Our finding shows that students performed better on equation-structure items compared to equation-solving items. This was expected since Matthews et al. (2012) item analysis showed that equation-structure items were easier to solve for students as opposed to equation-solving items. This could be because students were less familiar with the open-ended equation solving items or because students were less likely to produce operational patterns in equation-structure items because there were no blanks. The results support our thinking that solving arithmetic equations is challenging for students but more so for equation-solving items. Matthews et al.'s (2012) study showed the items become even more difficult for students when they are asked to use comparative relational strategies (shortcuts). We did not ask students to use shortcuts to solve problems. However, we investigated students' solution strategies in their responses to equation-solving items, and found that students' use of shortcuts remained very low in our study. Other studies showed similar results in the use of shortcuts to solve arithmetic questions which were low in school students (Fyfe et al. 2018; Rittle-Johnson et al. 2011). This finding provides further evidence that many of the participating students did not show the knowledge and skills (i.e. using efficient relational strategies) necessary to move to the most sophisticated level of the Construct Map (level 4), and illustrated that students rarely use comparative relational strategies when solving equation items.

In conclusion, there are two important aspects of this research that need some elaboration. Firstly, our findings contribute to the research literature, showing for the first time in South Africa that problems in understanding mathematical equivalence start in the younger grades. While it was grade 4 students who were tested, the knowledge needed for relational understanding of equivalence was subject to their learning experiences in the Foundation Phase. And the recommendations of the Essien (2009) study of grade 1 textbook and equivalence still remain relevant today. There is a need for curriculum change to include a more explicit explanation of the importance and meaning of equivalence as a big idea in mathematics in the Foundation Phase (Fyfe et al. 2018). This could involve the revision and redesign of the types of examples and activities used in class and textbooks as well as the assessment tasks given to students in the early grades. McNeil and Alibali (2005) suggested that excessive experience with traditional arithmetic examples leads students to develop operational patterns and prevents them from producing flexible strategies. We cannot expect our students to demonstrate the knowledge and skills needed to solve equations using relational strategies if we do not plan and use such examples in class. This is an important area for future research if we expect to influence change within our school curriculum.

Second, these results suggest that teachers need to pay greater attention to the meaning of mathematical equivalence in the early grades. Previous research shows that many teachers are not aware of the students' use of operational patterns and relational strategies (Jacobs et al. 2007) and most teachers underestimate the number of students who have an operational view of the equals sign (Asquith et al. 2007). This could also be the case with South African teachers. Vermeulen and Meyer (2017) showed, with a sample of three primary school teachers, that they lacked the knowledge and skills to identify, prevent, reduce or correct students' misconceptions about the equals sign. Future research is needed to investigate South African primary teachers' knowledge of and knowledge for teaching equivalence and this could inform the continuous professional development of both preservice and in-service teacher education.

Despite the contributions of the current research, there are some limitations that need to be mentioned. Firstly, the sample of schools was taken from quintiles 4 and 5 and does not represent the majority of students in our schools. However, it gives us some understanding of the knowledge of equivalence of grade 4 students, and highlights the need for further work in more diverse settings. Secondly, the test was administered in English only and in the middle of the grade 4 school year so some students may have had problems in understanding questions, and the results may not represent their knowledge of equivalence from the Foundation Phase only. Future research could consider whether these issues impact students' understanding of equivalence.

We conclude from this research it is imperative for students to develop and work with relational understanding of equivalence in the early grades to support their further success in mathematics.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this research article.

Authors' contributions

S.M., C.M. and E.S. contributed equally to this research article.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

Data is available from the corresponding author, upon request.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

References

Alibali, M.W., Knuth, E.J., Hattikudur, S., McNeil, N.M. & Stephens, A.C., 2007, 'A longitudinal examination of middle school students' understanding of the equal sign and equivalent equations', Mathematical Thinking and Learning 9(3), 221-247. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10986060701360902 [ Links ]

Asghari, A., 2019, 'Equivalence: An attempt at a history of the idea', Synthese 196(11). [ Links ]

Asquith, P., Stephens, A.C., Knuth, E.J. & Alibali, M.W., 2007, 'Middle school mathematics teachers' knowledge of students' understanding of core algebraic concepts: Equal sign and variable', Mathematical Thinking and Learning 9(3), 249-272. https://doi.org/10.1080/10986060701360910 [ Links ]

Baroody, A.J. & Ginsburg, H.P., 1983, 'The effects of instruction on children's understanding of the "equals" sign', The Elementary School Journal 84(2), 199-212. https://doi.org/10.1086/461356 [ Links ]

Capraro, M.M., Ding, M., Matteson, S., Capraro, R.M. & Li, X., 2007, 'Representational implications for understanding equivalence', School Science and Mathematics 107(3), 86-88. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1949-8594.2007.tb17773.x [ Links ]

Capraro, R.M., Capraro, M.M., Yetkiner, E.Z., Özel, S., Kim, H.G. & Küçük, A.R., 2010, 'An international comparison of grade 6 students' understanding of the equal sign', Psychological Reports 106(1), 49-53. https://doi.org/10.2466/PR0.106.1.49-53 [ Links ]

Carpenter, T.P., Franke, M.L. & Levi, L., 2003, Thinking mathematically: Integrating arithmetic and algebra in elementary school, Pearson Education, Heinemann, Portsmouth.

Department of Basic Education, 2011, Curriculum and assessment policy statement: Grades 4-6: Mathematics, Government Printer, Pretoria.

Essien, A., 2009, 'An analysis of the introduction of the equal sign in three Grade 1 textbooks', Pythagoras 69(1), 28-35. https://doi.org/10.4102/pythagoras.v0i69.43 [ Links ]

Essien, A. & Setati, M., 2006, 'Revisiting the equal sign: Some Grade 8 and 9 learners' interpretations', African Journal of Research in Science, Mathematics and Technology Education 10(1), 47-58. https://doi.org/10.1080/10288457.2006.10740593 [ Links ]

Fyfe, E.R., Matthews, P.G., Amsel, E., McEldoon, K.L. & McNeil, N.M., 2018, 'Assessing formal knowledge of math equivalence among algebra and pre-algebra students', Journal of Educational Psychology 110(1), 87-101. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000208 [ Links ]

Hattikudur, S. & Alibali, M.W., 2010, 'Learning about the equal sign: Does comparing with inequality symbols help?', Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 107(1), 15-30. https:/doi:10.1016/j.jecp.2010.03.004 [ Links ]

Hornburg, C.B., Wang, L. & McNeil, N.M., 2018, 'Comparing meta-analysis and individual person data analysis using raw data on children's understanding of equivalence', Child Development 89(6), 1983-1995. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13058 [ Links ]

Jacobs, V.R., Franke, M.L., Carpenter, T.P., Levi, L. & Battey, D., 2007, 'Professional development focused on children's algebraic reasoning in elementary school', Journal for Research in Mathematics Education 38(3), 258-288. https://doi.org/10.2307/30034868 [ Links ]

Jones, I., Inglis, M., Gilmore, C. & Dowens, M., 2012, 'Substitution and sameness: Two components of a relational conception of the equals sign', Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 113(1), 166-176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2012.05.003 [ Links ]

Jones, I. & Pratt, D., 2005, 'Three utilities for the equal sign', in Proceedings of the 29th International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education Conference, PME, Melbourne, pp. 85-192.

Kaye, D.B., 1986, 'The development of mathematical cognition', Cognitive Development 1(2), 157-170. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-2014(86)80017-X [ Links ]

Kieran, C., 1981, 'Concepts associated with the equality symbol', Educational Studies in Mathematics 12(3), 317-326. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00311062 [ Links ]

Knuth, E., Stephens, A.C., McNeil, N.M. & Alibali, M.W., 2006, 'Does understanding the equal sign matter? Evidence from solving equation', Journal for Research in Mathematics Education 37(4), 297-312. [ Links ]

Lee, J. & Pang, J., 2020, 'Students' opposing conceptions of equations with two equal signs', Mathematical Thinking and Learning 22, n.p. https://doi.org/10.1080/10986065.2020.1777364 [ Links ]

Li, X., Ding, M., Capraro, M.M. & Capraro, R.M., 2008, 'Sources of differences in children's understandings of mathematical equality: Comparative analysis of teacher guides and student texts in China and the United State', Cognition and Instruction 26(2), 195-217. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370000801980845 [ Links ]

Machaba, F. & Makgakga, S., 2016, 'Grade 9 learners' understanding of the concept of the equal sign: A case study of a secondary school in Soshanguve', in J. Keirk, A. Ferreira, K. Padayachee, S. Van Putten & B. Seo (eds.), Towards Effective Teaching and Meaningful Learning in Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, Proceedings of 9th Annual ISTE Conference on Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, Kruger National Park, Limpopo.

Matthews, P., Rittle-Johnson, B., McEldoon, K. & Taylor, R., 2012, 'Measure for measure: What combining diverse measures reveals about children's understanding of the equal sign as an indicator of mathematical equality', Journal for Research in Mathematics Education 43(3), 316-350. https://doi.org/10.5951/jresematheduc.43.3.0316 [ Links ]

McNeil, N.M., 2007, 'U-shaped development in math: 7-year-olds outperform 9-year-olds on equivalence problems', Developmental Psychology 43(3), 687-695. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.3.687 [ Links ]

McNeil, N.M., 2014, 'A change-resistance account of children's difficulties understanding mathematical equivalence', Child Development Perspectives 8(1), 42-47. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12062 [ Links ]

McNeil, N.M. & Alibali, M.W., 2005, 'Why won't you change your mind? Knowledge of operational patterns hinders learning and performance on equations', Child Development 76(4), 883-899. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00884.x [ Links ]

McNeil, N.M., Grandau, L., Knuth, E.J., Alibali, M.W., Stephens, A.C., Hattikudur, S. et al., 2006, 'Middle-school students' understanding of the equal sign: The books they read can't help', Cognition and Instruction 24(3), 367-385. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532690xci2403_3 [ Links ]

Molina, M. & Ambrose, R., 2008, 'From an operational to a relational conception of the equal sign: Third graders' developing algebraic thinking', Focus on Learning Problems in Mathematics 30(1), 61-80. [ Links ]

Powell, S.R. & Fuchs, L.S., 2010, 'Contribution of equal-sign instruction beyond word-problem tutoring for third-grade students with mathematics difficulty', Journal of Educational Psychology 102(2), 381. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018447 [ Links ]

Rittle-Johnson, B. & Alibali, M.W., 1999, 'Conceptual and procedural knowledge of mathematics: Does one lead to the other?', Journal of Educational Psychology 91(1), 175-189. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.91.1.175 [ Links ]

Rittle-Johnson, B., Matthews, P.G., Taylor, R.S. & McEldoon, K.L., 2011, 'Assessing knowledge of mathematical equivalence: A construct-modeling approach', Journal of Educational Psychology 103(1), 85-104. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021334 [ Links ]

Seo, K.H. & Ginsburg, H.P., 2003, '"You've got to carefully read the math sentence…": Classroom context and children's interpretations of the equals sign', in A.J. Baroody & A. Dowker (eds.), The development of arithmetic concepts and skills: Constructing adaptive expertise, pp. 161-187, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, NJ.

Vermeulen, C. & Meyer, B., 2017, 'The equal sign: Teachers' knowledge and students' misconception', African Journal of Research in Mathematics, Science and Technology Education 21(2), 136-147. https://doi.org/10.1080/18117295.2017.1321343 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Sharon McAuliffe

mcauliffes@cput.ac.za

Received: 31 Aug. 2019

Accepted: 24 July 2020

Published: 26 Nov. 2020

Note: Special Collection: Supporting Excellence in Early Childhood Mathematics Education.

1 . The terms 'students' views of the equals sign' and 'students' interpretations of the equals sign' have been used interchangeably in the literature. We used these terms interchangeably in this article.

REVIEW ARTICLE

Expanding vocabulary and sight word growth through guided play in a pre-primary classroom

Annaly M. StraussI; Keshni BipathII

IFaculty of Education, International University of Management, Windhoek, Namibia

IIDepartment of Early Childhood Development, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: This article is based on a study that aimed at finding out how pre-primary teachers integrate directed play into literacy teaching and learning. Play is a platform through which young children acquire language

AIM: This study uses an action research approach to understand how guided play benefits incidental reading and expands vocabulary growth in a Chinese Grade K classroom

METHOD: Data collection involved classroom observations, document analysis, informal and focus group discussions

RESULTS: The results revealed the key benefits of play-based learning for sight word or incidental reading and vocabulary development. These are: (1) teacher oral and written language learning, (2) learners' classroom engagement is promoted, (3) learners were actively engaged in learning of orthographic features of words, (4) learners practised recognising the visual or grapho-phonemic structure of words, (5) teacher paced teaching and (6) teacher assesses miscues and (7) keep record of word recognition skills

CONCLUSION: In the light of the evidence, it is recommended that the English Second Language (ESL) curriculum for pre-service teachers integrate curricular objectives that promote practising playful learning strategies to prepare teachers for practice

Keywords: guided play; cognitive development; literacy; sight word learning; explicit teaching.

Introduction

This article examines the use of directed play as a teaching and learning strategy during English Second Language (ESL) lessons in a Chinese Grade K classroom. Using a play-based strategy for teaching sight words may expand vocabulary. Play is an important vehicle for promoting language learning during early childhood and a developmentally appropriate way of teaching a range of skills and knowledge (NAEYC 2013). Playful learning refers to free play, whereas guided play is child-directed. Guided play also refers to learning experiences that combine the child-directed nature of free play with a focus on learning outcomes and adult mentorship. Guided play offers an exemplary pedagogy because it respects children's autonomy and their pride in discovery (Weisberg et al. 2016).

According to Copple and Bredekamp (eds. 2009:14), 'play is an important vehicle for developing self-regulation and for promoting language, cognition and social competence'. When young children do not gain an understanding and knowledge of the alphabet and its sound structure, the child will not be able to make connections to speak, read or write. Brown (2014:36) stated that 'learning to read is a developmental process'. According to the National Institute of Childhood Development, early reading skills can be grouped into categories with three elements: phonemic awareness, knowledge of high-frequency sight words and the ability to decode words.

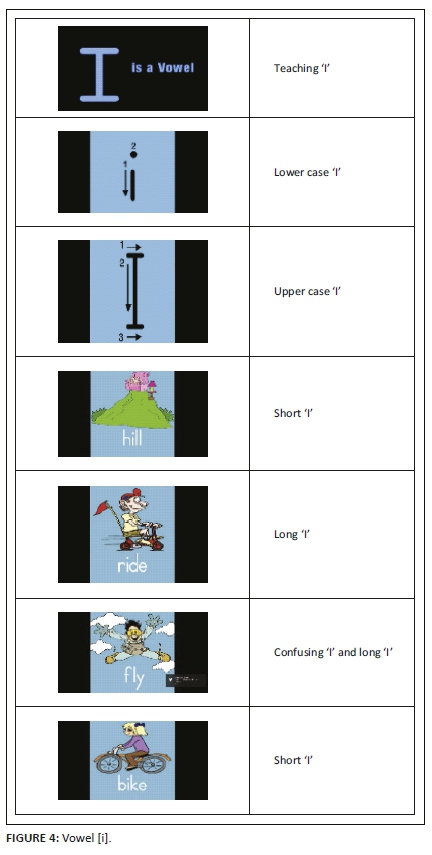

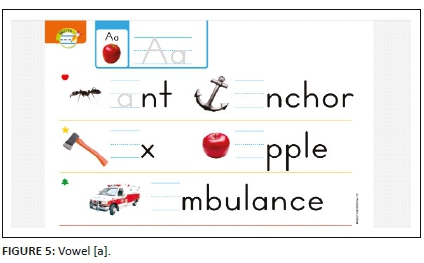

Letter names and letter sounds could be taught concurrently within an early literacy lesson. Letter name knowledge is defined as the ability to recognise and identify the letters of the alphabet, whereas letter-sound knowledge refers to the ability to recognise and pronounce the sounds that represent each letter of the alphabet (Mann & Foy 2003). For this article, sight words refer to automatic reading of high-frequency words. The article emphasises the role that the teacher can play in making play-based teaching and learning a developmental and education experience in second language classrooms.

In a comparison of Chinese and Namibian early literacy teaching and learning, the following features were prominent: (1) Chinese teachers have a monoculture, whereas the language culture of Namibian teachers in pre-primary learning communities differ from that of the learner and (2) basic education in China includes 3 years of compulsory preschool education (3-6 years), whereas Namibia has 1 year of preschool education (5-6 years) for those who can afford the service. Therefore, many learners may not benefit from language learning within these culturally vast and linguistically diverse environments of Namibia (Strauss & Bipath 2018). When pre-primary learners do not understand their teachers who speak a different native tongue, they may lose out on potential language learning. Unlike teaching and learning within a Namibian early childhood context, Chinese foreign language learning environments allow young children to gain meaningful language skills. Within these language learning environments, teachers provide environment-rich materials and experiences to encourage learners to explore the environment and their ideas through play (Epstein 2014). In a study, Frolland et al. (2013); Hood, Conlon & Andrews (2008) stated that home literacy teaching experiences are more important in developing emerging literacy skills. In the absence of these experiences, well-trained pre-primary teachers may provide literacy-rich experiences to affect children's language growth and learning positively. When teacher training prepares pre-service teachers to implement explicit play-based teaching and learning strategies it can bridge the gap that often exists between 'teachers' teaching beliefs and their classroom practices' (Strauss 2018:148).

Research argues that play and language learning go hand in hand (Zigler & Bishop-Josef 2009). Depriving children of play denies them vital opportunities to practice important cognitive and social skills that develop their imagination and creativity (Christie & Roskos 2000; Hirsh-Pasek et al. 2008; Pellegrini 2009). Pre-primary classroom contexts influence play activities and language learning for young children. To be particular, classroom environment and space arrangements are two key elements to enhance young children's play within the classroom context (Heidemann & Hewitt 2010). In highly structured didactic and overcrowded early childhood classrooms the role of play, and thus language learning is at risk. Overcrowded pre-primary classes, lack of resources and untrained early childhood teachers hamper children's possibilities to benefit from language learning. There is a need for pre-service teacher training in Namibia to explore play-based teaching and language-learning strategies that can advance teachers' classroom performance under such circumstances. Teacher training provides a terrain to expand the pre-service teachers' curriculum that may strengthen teaching and learning in practice. The question of this study is: How do teachers integrate play during literacy teaching to expand sight word and vocabulary growth in pre-primary classrooms?

Definition of play

Danniels and Pyle (2018) defined play as 'an enjoyable', intrinsically motivated behaviour that is non-rule-governed, non-goal-oriented and 'just pretend'. Play-based learning results from the active engagement of a child or the interaction between the child and peers and the environment. Young children need safe spaces for social interaction to promote play-based language learning. Genishi and Dyson (2009:61) indicated that 'play is a socially complex and communicative act'. These authors highlight the benefit of play and reveal that 'young children learn from their teachers about symbols and their use to take action in childhood worlds' (p. 82). On the other hand, Hughes (2010) argued that there is not a clear definition of play. Play is both play and work. Play allows children to manipulate objects, follow prompts, and apply their minds to create new worlds. Goodman (1994) cited by Hughes (2010:8) revealed that 'it is at the midpoint between play and work that the best teaching occurs'. Adults design the setting to highlight a learning goal whilst ensuring that children have the autonomy to explore within that setting. Autonomy allows young children the freedom to take initiative, be persistent and creative whilst gaining language skills during guided play. Copple and Bredekamp (eds. 2009) stated that early childhood professionals who employ a literacy engaging atmosphere where developmentally appropriate practices are used prove to have thriving and successful learners.

Theoretical underpinnings of play

Research shows that play facilitates intellectual growth. Bruner (1985) and Sutton-Smith (1967) maintained that play provides a comfortable and relaxed atmosphere in which children can learn to solve a variety of real-world problems, which may be of great benefit to them. Vygotsky (1978) argued that there are several acquired and shared tools that aid in human thinking and behaviour - tools that allow for clear thinking and understanding within a specific context such as teaching guided play. These tools are provided during formal instruction, and the role of parents and teachers is critical in transmitting their knowledge and beliefs to children (Maratsos 2007). Vygotsky (1978:102) further postulated that 'to play together, children construct imaginary situations in which meanings and perceptions have a "mediated" relationship'. Bruner's (1985) theory aligned with Vygotsky's (1978) sociocultural theory in terms of the zone of proximal development (ZPD), scaffolding and learning within a social community. Play provides this social community and serves as a vehicle to advance language and literacy development. The ZPD refers to the distance between children's 'actual' and 'potential' levels of development (Vygotsky 1978). When children independently solve problems, they function at the 'actual' level of development. Justice and Ezell (2001) indicated that some children may identify all alphabet letters, whereas others know very few concepts about print (e.g. alphabet knowledge, the directionality of print, the concept of word), whereas others know a great deal. Thus, the focus of teaching within the ZPD or effectively 'scaffolding children's understanding' is centred on allocating tasks that children cannot yet accomplish on their own, but that they can accomplish within the ZPD (Vygotsky 1978).

Language and literacy development

Hughes (2010:74) indicated that 'children are beginning to represent reality to themselves through symbols to let one thing stands for another'. When children start using a language they point to objects and people using words to name reality. Hughes (2010) termed this action 'symbolic play'. Symbolic or make-believe requires the ability to use symbols (McCune 1995 cited by Hughes 2010) and prepares young children for school literacy. Social experiences acquired through play lay the foundation for later reading and writing (DeZutter 2007 cited by Hughes 2010). When teacher training prepares pre-service teachers to use a variety of teaching and learning strategies for practice, children from diverse economic and language backgrounds may thrive in their language learning.

Literacy-rich environment

One of the characteristics of a high-quality classroom is that it exhibits an appropriate language-rich environment (Howes et al. 2008; Pianta et al. 2008; Thomason & La Paro 2009). Children who attend quality pre-kindergarten and pre-primary facilities know more letters, more letter-sound associations and are more familiar with words and book concepts than their peers who do not attend such a programme (Barnett, Larny & Jung 2005). As the classroom's physical environment provides the foundation for literacy learning (Morrow, Tracey & Del Nero 2011), teachers must provide the appropriate environment and materials that emphasise the importance of speaking, reading and writing. Providing space and props that focus on literacy that invites exploration, discovery and stimulates behaviours in which children and teachers are more engaged in teaching and learning activities for longer periods.

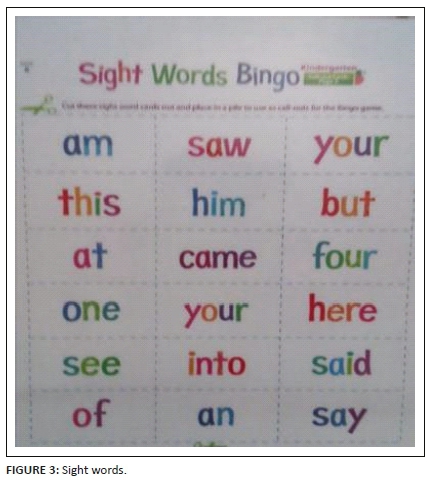

The term 'sight word' denotes to any word read automatically. High-frequency words are also known as sight words and learners should be able to read the words automatically and fluently (Brown 2014). Sight words refer to high-frequency irregularly spelt words, presumed to be impervious to decoding (Murray et al. 2019). Recognising words incidentally is important during early literacy development. Sight words stimulate learners' experiences and background so that meaning can be constructed from print. Print referencing occurs when an adult uses both verbal and non-verbal cues to guide an early reader's attention to language elements in the text. Johns and Wilke (2018) revealed that the beginning reader must learn at least 13 words at sight. These 13 words are a, and, for, he, in,is, it, of, that, the, to, was and you. Repeated exposure to sight words or matching pictures to text allows children to recognise orthographic patterns in words and as a result improve their sight vocabulary. According to Ehri (2014), orthographic mapping (OM) involves the formation of letter-sound connections to bond spelling, pronunciation and meaning of specific words in memory. Orthographic mapping is enabled by phonemic awareness and grapheme-phoneme knowledge. Orthographic mapping supports sight word reading and facilitates beginners to learn articulatory features of phonemes and grapheme-phoneme relations when letter-embedded picture mnemonics are taught. It explains how young children learn to read words by sight, spell words from memory and to acquire vocabulary words from print. Print experiences become helpful during individual reading when learners point to and track words in the text. Words should be meaningful and of interest to children to have a better understanding of the new words and what they mean for them (Johns & Wilke 2018 cited Hans et al. 2005). According to Justice and Ezell (2004), print experiences could serve as explicit techniques when making comments or providing explanations about concepts of print and the use of elaborative questions. Young readers who master sight words by late childhood will become efficient and effective readers (Johns & Wilke 2018).

The role of the teacher

It is the teacher's responsibility to set up the environment not by just adding words or labels, but adding meaningful print so that children can communicate and learn new information and concepts (Heroman & Jones 2010). The intentional teacher continually assesses each child's progress and adjusts his or her strategies to meet the child's individual needs (eds. Copple & Bredekamp 2009; Epstein 2014). In working with the teachers, Jones and Reynolds (2011) identified seven roles that teachers take on in children's play. These consist of the teacher as a 'stage manager, mediator, player, scribe, assessor, communicator and planner, observer and recorder' (Jones & Reynolds 2011).

The 'stage manager' is the role teachers take when setting up the classroom environment to include props and materials and allow time for children to play. The role of 'mediator' is when the teacher works with children to help them solve conflicts, teaching them problem-solving skills (Jones & Reynolds 2011). The teacher in the role of 'player', sustains play as the teacher participates in the children's play (Jones & Reynolds 2011). As a 'scribe', 'recorder' and 'observer' the teacher to identify the children's experiences as they play can find ways to support and enhance children's play (Jones & Reynolds 2011). As an 'assessor' and 'communicator' the teacher identifies what can be done to support children in the learning process (Jones & Reynolds 2011).

In the role of 'player', the teacher may inhibit children's learning by interrupting the play or directing it (Jones & Reynolds 2011). Encouraging teachers to plan for children's learning through play is not easily accepted, therefore, the role of 'assessor' and 'communicator' becomes necessary so that teachers can see how children learn as they played (Jones & Reynolds 2011).

Play-based learning

Play-based learning approach comprises 'play as peripheral to learning' and 'play as a vehicle for social and emotional development' as opposed to having 'play as a vehicle for academic learning' (Pyle & Bigelow 2015). When play is considered peripheral to learning the overall focus is on the teaching of academic skills that administration requires teachers to teach (Pyle & Bigelow 2015). Pre-service teachers can thus benefit from instruction to guide phonemic awareness and attention to sounds in spoken words to improve children's success in learning to read through play-based strategies. Evans (2005) revealed that reading printed text involves 'multilevel processing' at a letter, word, syntactic and semantic levels. Thus, there is a pressing issue about the relationship between kinds of reading and writing fostered in pre-primary schools, children's everyday experiences and teacher training.

Methodology

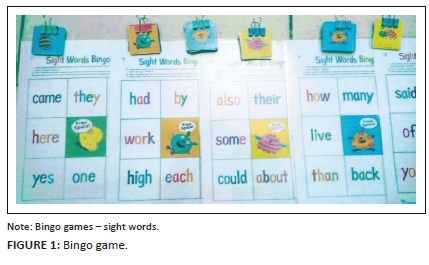

This study used an action research approach to explore play-based teaching that supports young children's language and literacy development in a pre-primary classroom. 'Action research has its goal to address a specific problem within a specific setting, such as a classroom, a workplace, a program or an organisation' (Merriam 2009:4). The study highlights the use of board games as a directed play-based learning strategy. During observations, data collection solicits and documents teaching and learning strategies that promote early literacy development and how play benefits incidental reading that expands learners' vocabulary. Action research is often conducted by 'people in the real world' who are interested in practical solutions to problems and who are interested in social change (Bogdan & Biklen 1998:234).

Data were collected using observations, documents, informal and focus group discussions. The analysis of data collected from observations, documents, informal and focus group discussions was performed using an inductive approach and critical discourse analysis. This analysis allowed for a more authentic picture of all experiences because the goal of the inductive analysis is to use the literature or a theoretical framework to anticipate themes and let them develop as the study proceeded (Corbin & Strauss 2008). Furthermore, all lessons were video recorded and field notes were taken during the observations and focus group discussions. During these discussions, the researcher gained an understanding of Chinese teachers' teaching and learning practices. The video recordings focused on the teachers' teaching actions only. These recordings allowed the researcher to replay the teaching experiences, imagining solutions for practice, modifying ideas and reflections for action. In the analysis of documents, descriptive discourse analysis was used. Rogers (2011) indicated that print literacy practices - reading and writing - are privileged in school settings and foregrounded visual modes (gaze, print) for accessing textual information through primarily paper media (Kress 2010) as revealed in the play-based activities that supported language learning. Peer reviews included informal chats and reviews of video recordings with ESL teachers. This process is known as 'member checks' (Merriam 2009) to rule out any misinterpretation of the teachers' teaching details. During repeated visits for 1 month, data were collected and a review of documentation, observations of literacy teaching to promote language and literacy development and field notes noted during informal 'chats' and focus group reviews with teachers were also included.

The ethical route to obtain permission from the school principal and participants was followed (See acknowledgement of the study). It is important to minimise any threats that included the procedures, treatments or experiences of the participants that change or threaten the researcher's ability to gather correct details or draw incorrect inferences (Creswell 2009). To ensure the validity of the research design, the researchers utilised several data collection strategies. To triangulate, we coded the data collected, using sources that include observations, documents and field notes. For a code to be valid it had to be evident in more than one data source (Merriam 2009).

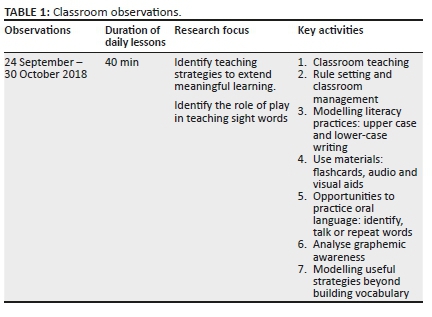

Participants