Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Childhood Education

On-line version ISSN 2223-7682

Print version ISSN 2223-7674

SAJCE vol.10 n.1 Johannesburg 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v10i1.709

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

The triple cocktail programme to improve the teaching of reading: Types of engagement

Geeta B. Motilal; Brahm Fleisch

Division of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: South African-structured reading programmes have been implemented in schools in South Africa. The Early Grade Reading Study (EGRS) is an education triple cocktail programme, which attempts to improve home language reading in a number of schools.

AIM: The objective of this research was to find out how the educators involved in the implementation of the triple cocktail intervention programme enact the implementation of the lesson in the classroom. The second objective was to ascertain whether there were any effects in improving the teachers' knowledge and skills bringing about changes to their practice.

SETTING: The context of the study were four primary schools from the North West province that participated in the EGRS study. Foundation Phase teachers from these schools where the home language is Setswana were selected to be the participants of this study.

METHODS: A case study approach using an interpretive paradigm provided an empirical comparison of the effects of different types of implementation that can affect the outcomes of the programme. Foundation Phase teachers from four schools participating in the EGRS were observed in their classrooms and interviewed to gather data

RESULTS: The Guskey's model for teacher change was used to analyse the data, focusing on teacher change and the professional development of teachers.

CONCLUSION: The results indicate that enactment of new approaches to early grade reading teaching can happen in four different ways. Teacher change occurs gradually and within a paradigm of mentoring and coaching.

Keywords: reading; intervention programme; fidelity of implementation; reading strategies; teacher change; professional development.

Introduction and background

According to various researchers (Fleisch 2009; Spaull 2013; Taylor 2013), education in South Africa is in crisis. International tests such as the Southern and Eastern Africa Consortium for Monitoring Educational Quality (SACMEQ) II (2011), Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMMSS) (2015), Howie et al. (2017), and Alitnok (2013) provide a picture of the crisis that we face. The PIRLS Howie (2017) report indicated that the biggest developmental challenge facing South Africa is the large number of children who do not learn to read for meaning in the early years of school.

Over the past decade, there has been a growing recognition that a substantial proportion of South African school children perform one or more years below acceptable levels of achievement, particularly in key subjects such as English First Additional Language and Mathematics National Education Evaluation and Development Unit (NEEDU) (NEEDU 2013; Spaull 2013; Taylor 2014). Spaull (2015) argues convincingly that school children who are academically behind in the Foundation Phase are likely to fall further and further behind their peers as they progress through the school system. This is clearly not a conventional 'remedial' problem, in which a small number of individuals in a class have specific learning barriers or challenges. The learning deficits are systemic, often affecting almost all the learners in the majority of disadvantaged schools.

The Department of Education has implemented a number of interventions (Gauteng Primary Literacy and Mathematics Strategy [GPLMS] in Gauteng, Early Grade Reading Study [EGRS] 1 in the North West province, EGRS 11 in Mpumalanga, National Education Collaboration Trust (NECT) and Primary School Reading Improvement Programme [PSRIP]) in an attempt to improve learner outcomes. One of these initiatives is the EGRS, which was introduced in 230 schools in two provinces - North West and Mpumalanga provinces. The aim of the EGRS 'triple cocktail' programme1 is to fulfil the Department of Education's vision and mission to increase the number of learners in Grade 3 and to improve the professionalism, teaching skills, subject knowledge and computer literacy of teachers throughout their career (De Clercq & Shalem 2015).

High-quality professional development for teachers is critical to proposals that improve education (Guskey 2002). Guskey (2002:387) emphasises that schools 'cannot be better than the teachers who work in them'. The teachers' knowledge, skills, pedagogy and professionalism are central to what is taught and how it is taught. Many of the teachers are untrained or semi-trained Foundation Phase teachers, especially in rural and semi-rural schools, as they received no specialised training to teach in this highly specialised phase although they are qualified teachers.

The EGRS programme was designed to support educators to build a professional knowledge base in teaching that achieves the following three objectives:

-

to provide the practice of teaching is deprivatised through the use of structured lesson planning, support from coaches and resources

-

to improve professionalism and teaching skills by accumulating professional knowledge over time and sharing this knowledge as teachers implement the programme in the classroom

-

to develop improved practice through collaborative refinement and ongoing practice of lesson plans and pedagogy.

The aim of the EGRS programme was to provide the teachers teaching Setswana to Grades 1, 2 and 3 learners with training in how to teach learners to read, using strategies stipulated in the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS).

The programme provided a 'triple cocktail' intervention programme, providing teachers with lesson plans, reading materials and coaching, together with pedagogical training. The training took place in two sessions and was implemented at the schools where the research was conducted. Schools in the first training group had no coaches, while schools in the second group were assigned coaches for up to 1 year.

Two cohorts of teachers were trained: (1) Group 1 used teachers who received EGRS training to teach literacy using different reading strategies - this group is called 'training teachers' for the purpose of this article. (2) Group 2 received the training but were given coaching support when they began implementing the programme - this group is called the 'coaching teachers'.

The defining characteristic of the model used for the EGRS Group 1 was the use of trained teachers without coaching support for the first set of schools and coaching teachers who received coaching support for the second set of schools. The programme clearly indicated the importance of the one-to-one relationship between the teacher and the coach, which was designed to support continuous professional development (CPD) for a period of 1 year. While the teachers who were coached had this experience in common, Group 1 teachers were not offered this support. The teachers who were coached received skills-based support and monitoring from their coaches.

In a mentoring or coaching model, relationships can be collegial, for example, in the use of peer coaching. This form of coaching may be hierarchical because the new teacher will be guaranteed a 'supporter' who supports the CPD process which is being implemented. It also involves the assessment of the new teacher's competence; and in this case, the assessment is carried out against the key principles of the EGRS 1 intervention programme.

In the coaching and/or mentoring model, professional development takes place within the school context by sharing learning between colleagues and also by keeping an open dialogue between the coach and the coachee. This model can be enhanced further by providing on-site coaching in the form of face-to-face interactions or off-site support via WhatsApp messages. These types of coaching can help teachers improve their knowledge and skills while implementing the programme.

From early results and despite the training provided, the following was observed at the end of the first year of the study.

The vast majority of learners in the 230 schools did not develop substantial reading skills during the first year of schooling. From our sample, we found that 13% of learners could not identify a single letter correctly, 29.5% could not correctly read a single word and 65% scored zero in the sentence reading section. In the full sample, the mean score for the number of letters correctly identified was 22.7, the average number of words correctly read at the end of Grade 1 after three interventions was only 7, and when reading sentences, no more than four words in each sentence were identified correctly in sentence reading (notes on the EGRS 1 midline results).

It is clear from these midline results that after the implementation of the structured programme the schools still struggled to show improvement in reading. These findings are consistent with Spaull's study of oral reading fluency, which found that by Grade 5, a substantial number of learners scored zero on reading fluency, with most learners reading below 40 words a minute. The EGRS 1 study clearly shows that the slow reading progress is already evident in Grade 1 (Spaull 2015).

Given the above, it became apparent that the Foundation Phase educators who were part of this programme did not implement the EGRS programme as expected. The main concern lies around the implementation of the EGRS programme. To investigate the tensions and problems, we conducted a study that explored:

-

How did the educators enact the implementation of the EGRS intervention programme?

-

Did the training provided by the EGRS intervention programme change teachers' practice?

The objective of this research was first to find out how the educators involved in the implementation of the triple cocktail intervention programme enact the implementation of the lesson in the classroom. The second objective was to ascertain whether there were any effects in improving the teachers' knowledge and skills bringing about changes to their practice.

The objective was to report on the variety of ways and degrees to which teachers enact the new lesson plans in their Foundation Phase classroom. In addition to exploring the ways teacher enact the lesson plans, we investigated teachers learning from the lesson plans, the educational materials, the training and the coaching process.

Literature review

This study is nested in three specific research literatures. There is a growing set of published research papers on the Early Grade Research Study itself, and this case study responds to and extends the findings of these predominantly quantitative papers. The second literature is broader and explores a key theme in large-scale change, that is, the challenge of fidelity. The final literature draws on research on how teacher learning takes place. The latter two areas of research inform the theoretical framing of this study.

The early grade readers study

Improving the quality of education in developing countries such as South Africa has been a huge challenge and has received much attention since the inception of democracy in 1994. Because of this there has been a plethora of interventions aimed at affecting change such as the EGRS programme together with the evaluation of these. The Department of Basic Education (DBE), non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and researchers have written a number of papers and reports on the EGRS programme.

The early grade reading programme in South Africa drew on the design features and the lesson plans in particular that were developed for the GPLMS that was implemented in the Gauteng province in 2010. The GPLMS was evaluated using a Regression Discontinuity Design, but suffers from various limitations in the identification of a control group and with the outcome data. Notwithstanding these limitations, both the implementation and the evaluation of GPLMS suggested that a high-quality structured learning programme supported by instructional coaching could be effective at a relatively large scale (Fleisch et al. 2016). This was the basis of the EGRS. To implement the EGRS in schools, the Theory of Change was used to underpin the EGRS programme. The Theory of Change is grounded on training, understanding, trying, evaluating and change, which is an iterative process of progress in teaching and learning of reading in the early grades. The programme ran three different interventions in the North West province, which all targeted home language literacy (Setswana).

The EGRS was designed and implemented in these schools from Grade 1 in 2015 and Grade 2 in 2016. The study showed that two methods were used: one with lesson plans and training at centralised workshops twice a year, and the second method provided ongoing support to teachers through onsite coaching and small cluster training sessions (triple cocktail method).

In notes by the Zenex Foundation (Taylor, 2016) from a panel presentation by Taylor, he explains the need for the EGRS and a research agenda. The research agenda that the DBE embarked on is focused on understanding of how to improve the teaching and learning of reading in the early grades. This research agenda elucidates on how qualitative research is usually conducted in small scale and how it is exploratory, hypothesis-generating and deals with fine-grained questions of how, why and when (Taylor 2016).

A study by Mabuza (2017) states that an early grade Setswana reading improvement of about 40% in Setswana at selected schools in the North West province (Mabuza 2017), a result of an evaluation conducted by the DBE. The study found that the coaching intervention showed a substantial positive impact after the end of Grade 2.

The results of the EGRS were also reported in another meeting report. This report specifically highlighted the findings that girls were outperforming boys, large classes did not seem to limit children's progress and the impact of the interventions was seen mostly in urban schools as opposed to rural schools.

Fidelity of implementation

The fidelity of implementation, according to O'Donell (2008:36), 'is traditionally defined as the determination of how well an intervention is implemented in comparison with the original programme design during an efficacy and/or effectiveness study'. More specifically, it is 'the extent to which the user's current practice matche[s] the … "ideal"'. 'Fidelity of implementation is a relatively recent construct in K-12 curriculum intervention research, but its use in programme evaluation dates back 30 to 35 years' (Mowbray, Holter, Teague, & Bybee, (2003); as cited in O'Donell 2008:34).

The fidelity of implementation, therefore, involves the application of tools and procedures designed for the specific programme to ensure that the implementers replicate it exactly. It is to strictly control implementation to make sure that programmes are effective. There is an expectation that the implied methodologies proposed by the programme will make the programme effective. The EGRS is one programme which provides lesson plans, tools and procedures and strictly controls implementation. Thus, teachers are compelled to pursue the fidelity of implementation. Exact reproduction is an integral part of the programme, although it may produce different effects in different circumstances. Many other variables exist, and the main variable that may affect the implementation of the programme is the context. It is difficult to accommodate different contexts.

Integrity of implementation

The idea of integrity of implementation allows for 'programmatic expression in a manner that remains true to essential empirically-warranted ideas while being responsive to varied conditions and contexts' (LeMahieu 2011:6, 8). Thus, integrity of implementation 'addresses real problems of practices and generates knowledge that genuinely improves practice'. This comes from the theory of improvement science and improvement research. In order for the integrity of implementation to be realized, the programme design and the implementation strategies require more flexibility. LeMahieu (2011) recognises that when we design for implementation we design differently.

Finding the right pieces does not constitute the key to success but figuring out how to make the pieces fall into place as you go. Implementation, therefore, not only requires rigour but also requires juggling and perception to make it successful.

The teaching of reading

In the last 100 years, there has been an unprecedented and multidisciplinary research into reading (psychology, psycholinguistics, sociology, linguistics and theories of learning). Goodman (1967) and Goodman and Gollasch (1982) defines reading as a psycho-linguistic puzzle, which involves a process of prediction, reading, confirmation, re-reading, which is applied to whole texts and to words. Larson (2004) describes reading as a science of word recognition, eye movements moving back and forth over the text. Rumelhart (1980) describes reading as a process that requires the use of three cues as we read: the grapho-phonics, the semantic and the syntactic cues. Reading includes different neurological pathways, which change as we become expert readers using language, logic and memory centres of the brain (Woermann et al. 2003).

Intentional instruction

Zimmerman (2001) asserts that reading requires both cognitive and metacognitive strategies as a complex, strategic process. Teaching reading in any language requires the mediation of a set of skills that the proficient reader uses, namely, cognitive reading strategies. Doing so involves 'deliberate, goal directed attempts to control and modify the reader's efforts to decode texts, understand words, and construct meaning of texts' (Afflerbach, Pearson & Paris 2008:368, 369). To master the required skills, 'readers need to have attained a level of metacognitive awareness, including declarative, procedural and conditional knowledge'. Sailors and Price (2015) have dubbed these cognitive and metacognitive strategies 'intentional instruction'. In their observation of the reading lesson, the researchers observed whether the teachers did the following:

-

provided 'opportunities for children to engage in reading strategies'

-

identified 'the strategies required during reading'

-

explicated and discussed with learners 'their own cognitive' process during reading (Sailors & Price 2015:118).

According to Reynolds, Wheldall and Madelaine (2011:257), many researchers found that '… all aspects of the reading process need to work together in harmony in order for a child to be a competent reader' (Ehri 2003; Snow, Burns & Griffin 1998; Stuart, Stainthorp & Snowling 2008). As reading is a complex process, many things '… can go wrong during the acquisition process, resulting in difficulties and breakdowns in getting the complementary parts of the reading process working together smoothly' (Reynolds et al. 2011:257).

Acquisition of oral language

In acquiring a language, oral language forms the basis to learn a language. The main component of oral language is the development of vocabulary. According to Fielding, Kerr and Rosier (2007):

[… O]ral language consists of phonology, grammar (syntactic), morphology, vocabulary, semantics, discourse and pragmatics. The acquisition of these skills often begins at a young age, in a child's home language, before they begin focusing on print-based concepts such as sound-symbol correspondence and decoding. Because these skills are often developed early in life, children with limited oral language ability are typically at a distinct disadvantage by the time they enter kindergarten. (p. 489)

Oral language is the foundation of learning a language and begins in the early stages of development beginning as early as 4 years old. Oral language development has a significant effect on the children's preparedness for preschool and their academic achievement in Foundation Phase and throughout their academic career. Children enter school with a wide range of background knowledge and oral language ability because of their own home experiences, exposure to language from their adults at home, in their environment and resources available in their socio-economic status (SES) (Fernald, Marchman & Weisleder 2013; Hart & Risley 1995). Gaps result in academic ability because of the same factors and continue to grow throughout their school experience (Fielding et al. 2007; Juel et al. 2003), which is why a strong focus on the development of oral language in the early years is imperative for learning and academic success. Oral language plays a critical role in reading instruction, comprehension, writing and assessment and has implications for classroom teachers. Thus, the role of oral language in reading is critical for children to progress in their learning.

Researchers, such as Catts et al. (2001:40), found that children with oral language impairment 'are more likely to present with reading difficulties than their peers'. In addition, children who struggle with phonemic awareness in their early years have difficulty acquiring phonic word-attack strategies and struggle with decoding. Also, researchers such as Foorman et al (2015) state that the 'child's level of vocabulary significantly impacts reading development, but there is debate about whether or not it is only vocabulary or if reading acquisition is affected by all of the oral language components of syntactic, semantic and grapho-phonic'. A recent study of reading comprehension finds that 'both reading accuracy as well as oral language skills, rather than vocabulary alone, predict performance on outcome measures' (Foorman et al. 2015:17).

Oral language affects all the components of reading such as word recognition, comprehension and reading fluency. Cain and Oakhill (2007) emphasise that:

[N]ot only are oral language skills linked to the code-related skills that help word reading to develop, but they also provide the foundation for the development of the more advanced language skills needed for comprehension. (p. 31)

The diversity that exists in a classroom poses immense challenges for teachers who teach children how to read. Teachers require to assess each child's need and provide sufficiently powerful instruction to meet the needs of each student.

Professional development and teacher change

The notes by Zenex Foundation (Taylor, 2016) explain that when implementing a pedagogical intervention in schools one is actually trying to change teacher practice on scale. According to them, this is 'the central challenge, quite aside from intrinsic quality of the new pedagogical methods. One is trying to change the ingrained behaviours of teachers with whom one has limited contact …' (Taylor 2016:2). It is for this reason that this study sought to understand teacher change from the EGRS interventions.

One of the core assumptions in the theory of action in the EGRS study is that external interventions lead to changes in teachers' instructional practices, which, in turn, lead to changes in learner achievement or outcomes (Cilliers et al. 2019). This assumption, therefore, envisages a level of professional development and teacher change. There is also a growing consensus that the professional development of teachers lies at the centre of educational change and instructional improvement (Elmore & Burney 1997). In South Africa, continued professional development is the most effective method of bringing about changes and to provide quality education for children in the post-apartheid period.

To address issues of equity, programmes such as the EGRS are used to develop teachers, to facilitate the expansion of their knowledge and skills, to contribute to their growth and competency and to implement instructional strategies that enhance the teachers' content knowledge, pedagogy and teaching styles. Providers of professional development should recognise that change is a gradual and difficult process for both new and seasoned teachers. It is essential to ensure that teachers receive regular feedback on student learning, as well as ongoing follow-up, support and guidance (Guskey 2002).

Guskey (2002) points out that for the sake of becoming better teachers, most teachers engage in professional development programmes because of the contractual agreements. Guskey adds that the teachers perceive professional development as an opportunity to grow in their jobs and upgrade teaching and learning in their classrooms and to improve their learners' outcomes.

Theoretical framework

The theoretical framework, which underpins this study, is Guskey's model of teacher change.

This study used a model of teacher change (Figure 1) that is about 20 years old (Guskey 1986). Guskey adds that the model depicts the sequential progression from professional development experiences to sustainable change in teachers' beliefs and attitudes. This particular model of Guskey afforded the opportunity to gauge if there was any change in students' outcome and in teachers' beliefs and attitude by observing teaching and learning and by interviewing the teachers (Guskey 2001).

Research methodology

The goal of the research was to gain an understanding of the enactment of the EGRS programme in four schools by using an exploratory case study design (Yin 2008). The use of the case study approach allowed for methodology flexibility (Denzin & Lincoln 2000). Cresswell et al. (2007) states that a:

[Q]ualitative study is defined as an inquiry process of understanding a social or human problem, based on building a complex, holistic picture, formed with words, reporting detailed views of informants, and conducted in a natural setting. (p. 645)

Qualitative research involving an interpretive and naturalistic approach was employed to describe classroom observations and perspectives from teachers' interviews taken 'from their natural settings, attempting to make sense of, or to interpret phenomena in terms of meanings people bring to them' (Denzin and Lincoln, 2005:6)

Context of this study

The context of this study is of particular importance in this inquiry. The research sites of this study were four schools from the North West province that participated in the EGRS study. Two rural schools and two farm schools were selected. The number of learners in the classroom varied between 19 and 36 learners. The research was based on classroom observations and semi-structured interviews of seven teachers who were part of the EGRS programme.

Participants

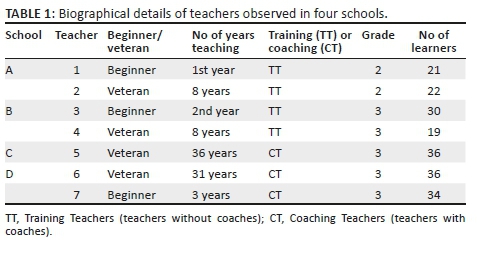

To add precision to the researchers' estimates, the teachers were categorised, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1 refers to beginner teachers and veteran teachers. The beginner teachers are those teachers who are new to the profession and have taught between 1 and 3 years. The veteran teachers are the older teachers who have taught from 8 to 36 years. The Department of Education (DoE) and Class Act selected the participating schools and teachers. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Human Sciences Research Council for the larger study.

Research methods

A self-designed observation schedule was used to record observations made in the classroom. An interpreter was used to interpret the lesson as it was taught in Setswana. The observation schedule enabled the researcher to gather first-hand information on the enactment of the lessons in the Grade 2 or Grade 3 classrooms. The strength of this schedule was that it yielded information on the existing situation and allowed for the information to be captured and recorded immediately.

The second method was the semi-structured interview of the teacher. This allowed the teacher to give her perceptions of the programme and gave insight into her attitude as a teacher and implementer of the EGRS programme. The strength of the interview was that it helped clarify any misconceptions of the viewed lessons and to provide additional information about the EGRS training and implementation of the programme.

Data generation

The researcher visited the schools and observed selected classrooms together with an interpreter, the district official and the coaches over a 2-week period in August 2017. Letters of consent were delivered to the principals and each of the participants with a cover letter explaining the purpose and significance of the study.

Data presentation and analysis

As the nature of inquiry was exploratory, descriptive and contextual, descriptive statistics (Leedy & Ormrod 2005) were used to discuss the trends and analyse the data. The classroom observations were conducted during each teacher's facilitation of a reading lesson and were documented in field notes. The field notes were analysed after each observation, as recommended by Braun (Braun & Clarke 2006). The researcher compared the opportunities that the teachers provided for learners to engage in cognitive reading strategies and the instructional strategies actually used. We also looked at the interactions between teachers and learners, specifically taking note of how the teachers explained and used the strategies. We also examined how the training model and the coaching model may have contributed to changes in teacher attitude and practices and the learners' ability to read with meaning.

This article presents a perspective on the enactment of teachers in implementing the 'triple cocktail' programme and the teacher's perspective of teacher change. It examines teachers' attitudes, perspectives and instructional changes, how particular types of change occurred and how specific types of change can be facilitated and maintained. It proposes a model for viewing change in teachers that can assist in improving learning.

Ethical consideration

Ethical clearance for this study was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the Human Sciences Research Council (ethical clearance number: protocol number REC 8/19/02/14). The Department of Basic Education granted permission to conduct the research in schools.

Findings and discussion

The data were analysed around two broad sections, namely, 'Fidelity of implementation' and 'Teacher change'.

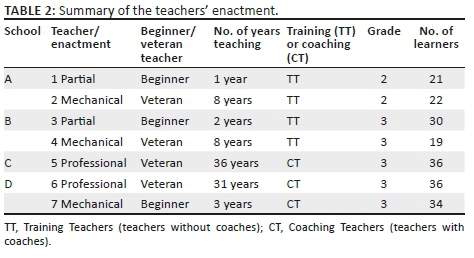

The results demonstrated in Table 2 emphasise that the selection of teachers in terms of experience and training received without coaches and with coaches increased the complexity of the implementation in the research context.

Fidelity of implementation

Most of the teachers underwent two sets of training. They were trained to use the lesson plans and to identify the instructional strategies to teach reading. They were shown how these strategies work in the classroom. To the teachers, these strategies were 'new' and most of them said that they had never used them before.

Teacher 1 said:

'I thought the training was really good. After the training I started implementing creative writing strategies in the classroom by using discussion and examples to show writing. I started giving learners homework from the Workbook. I also began using shared reading and group guided reading strategies. I also started using shared writing strategies and then moving to individual writing. If I struggle (with my teaching), I send them to the principal, who attended the EGRS training as well. Learners have improved a lot. They are reading more with understanding, do handwriting (cursive) lessons.' (Teacher 1, School A, 1st year of teaching)

Although this teacher tried to implement the EGRS lesson to the best of her ability, she struggled with the implementation without a coach. She admitted to being able to use some parts of the programme such as teaching phonics and doing some shared reading, therefore, managed a partial implementation of the programme.

In this empirical qualitative case study, the concept of fidelity of implementation refers to the implementation of a structured pedagogical programme in education. It clearly showed that four types of enactment exist when a programme is implemented.

Not at all

Firstly, we can gauge if there is a 'Not at all' response from the teachers. Although this was not evident in this data, the possibility exists where there would be no take up of the programme.

Partial enactment

Secondly, we can see a partial or incomplete enactment. This was observed when a group of teachers taught the first part of the lesson demonstrating the introduction of the lesson and did not want to complete the remaining activities. As a result, these teachers did not complete the entire lesson as set out in the lesson plan.

Mechanical enactment

The third type of enactment is best characterised as mechanical. In some classrooms, we observed a formal or mechanical enactment, with little understanding of the underlying rationale for the new approaches. They followed the lesson plans in a structured, mechanical way to appear to be on task. They went through the whole lesson in a perfunctory manner by going through the motions of the lesson as set out in the lesson plan without understanding the purpose of each part of the lesson or thinking about the development of higher order skills. It clearly showed that the teachers were able to follow the new routines but lacked both in content knowledge and metacognitive knowledge required for greater rigour.

This enactment was evident when, for example, the group-guided reading strategy was being implemented. The groups were set up according to reading ability groups. Learners were called to sit in a group with the teacher and given individual basal readers. However, when implementing the group guiding strategy children read in 'groups', more in unison, in chorus or in a 'round robin' manner. There was no evidence of the use of decoding skills, use of syllabification or picture cues, individual reading and using the five-finger strategy to recognise words and the use of comprehension strategies to develop meaning. As a result, very little reading for meaning took place as comprehension and understanding of the story was not discussed.

Professional implementation

Professional competency in the teaching of reading has been recognised as an educational priority at all levels of formal education (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO] 2005), and it has been proposed that learners should be empowered to act in ways that increase their ability to read for meaning. Professional implementation of the EGRS intervention programme targets to enhance the teacher's professional competence by improving their pedagogy. Some of the teachers developed a good sense of the programme and navigated through set lesson plans by adapting and using content knowledge and pedagogical skills to implement the strategies for teaching reading. Lessons for these teachers catered for the individual learners in the classroom, helped integrate other learning and made reading more meaningful. The lessons allowed for metacognitive development. This was difficult to observe in most of the teachers' classrooms. Two teachers in particular demonstrated these characteristics. The teacher was able to adapt the lesson plans, components of the structure, adopting and changing key methodologies and using higher thinking order skills.

Therefore, one of the key findings of this research was around the implementation of the EGRS intervention programme. There were four different types of responses by the teachers to this structured pedagogical programme. It was evident from the teachers observed that, firstly, there was mixed implementation of the programme. Secondly, it was found that the teachers were using time and space more effectively. Thirdly, it was found that when implementing the intervention programme with fidelity there were two ways of implementing, namely, mechanical implementation and professional implementation.

Teacher change

Another finding of this research shows that teachers' professional development does not adhere to the principles of Guskey's model.

Change in learner outcomes

Unlike teacher 1, others reported very little change in learner outcomes, which contradicts what teacher 1 said. These teachers all felt that although they had tried to implement changes, the overall outcomes showed little or no improvement. Guskey (2000:388) regards this as a 'crucial point of professional development as the experience of successful implementation that changes teachers' attitudes and beliefs resides in the outcomes'. Constant reflection and feedback on students' successes is a catalyst for change. Students' successes contribute to empowering teachers to be positive about the changes they made in their teaching and thereby making more changes. However, 50% of the teachers were not provided with coaches and thus received no feedback, with the result that they were left on their own to implement changes and reflect on their practice. In the case of these teachers, there was partial implementation. Without any feedback and very little success indicated that the teachers were not overly enthusiastic with their efforts.

Where there were coaches, the teachers said:

'After I implemented the EGRS programme I find that the learners have improved, they can read better and those who are struggling are getting more help. The coach is very good and we were grateful for getting resources. I could now WhatsApp the coach if I did not understand anything. Although everything is great now, there are some learners who are very slow. Time is the main challenge.' (Teacher 5,6 and 7, School C and School D, Grade 3 teachers)

The learners are performing 'great' after implementing the programme. When doing revision, they showed understanding. However, while writing assessments, they wrote something else. They cannot read and understand instructions on their own. They cannot read for meaning.

This teacher worked at a school that had a coach, and the subject advisor was also present regularly. The teacher said that the coach taught her and guided her, and she really appreciated the help. The EGRS intervention programme had helped her in teaching phonics, writing, reading and diary-writing in Setswana lessons and in teaching English as well. She had also been shown how to organise a spelling bee. There was a change in pedagogy as she was using the innovative strategies. The teacher said, 'after the training I started implementing creative writing strategies in the classroom by using discussion and examples to show writing' (Teacher 1). Her teaching practice and methodology had changed over time, and she knew her learners better. Her learners were now writing simple sentences, but they did not always construct what she had asked for.

However, although professional development had taken place and was followed up with coaching, a minimal success rate was reported. Teachers had committed to the change in practice but with the 'guarded' outcomes of learners and the continuous struggle of the teachers, they became disillusioned and resorted to laboriously following lesson plans without any passion for their work. One can assume that this supports the idea that changes in teachers' attitudes take place primarily after there is evidence of change in student learning. In this case there was partial implementation.

Where there were no coaches, the situation was more depressing, as learner outcomes did not improve. One of the teachers indicated that:

'The training did not provide a coach and I was left on my own to continue teaching as I remembered my training. There was no further guidance and no one came to see me teach. I am visited for the first time by the researcher.' (Teacher 4, School B, teaching for 8 years)

In this case, the teacher indicated clearly that coaching might have had an impact on the reading achievement of learners from participating classrooms. She did not know how to work with the time she was allocated to do reading. She did not understand that time should allow for flexibility. She said:

'I found that the time is too short to implement the EGRS programme as she would like. I have a number of slow learners and I struggle to finish the work in the given time. The work accumulates and I cannot be finish by the time the spelling test is written on Friday.' (Teacher 4, School B, teaching for eight years)

This teacher needed to be shown how to use time on task. The support that she required was to be given more resources and a complete supply of reading books. Another teacher said, 'Although I manage with time better, it is still a struggle due to the expectations from the tight lesson plans'. These teachers were negatively affected, and their attitude towards the changes was hostile. One teacher remarked rudely, 'I do things for the sake of doing it. I do not understand the strategies fully'. She admitted that she did not actually teach to improve herself as a teacher.

According to a study performed by Kuzborska (2011), intervention programmes in the early stages tend to create, '… high anxiety and confusion amongst most teachers'. After 6 months, teachers should have cognitively mastered individual teaching skills, but the teachers showed that they 'had little sense of integration of separate parts or, more globally, how certain skills or exercises are related to specific outcomes' (Guskey 2000:365).

Sailors and Price (2015:124) agreed with (Guskey, 2000) findings, which 'align with research that demonstrated that teacher explicitness in cognitive reading instruction leads to an increase in reading achievement on the part of students'. If the participating teachers were given an opportunity to explain the reading strategies, talk to coaches about them and reflect with other teachers, there would be significantly greater awareness and understanding of the strategies. Teachers can be taught to be strategic in their thinking (Pressley 2000) and to make their learners strategic in their thinking (Pressley 2000). A more intensive model of professional development for classroom teachers is needed to provide the context of such learning (Sailors & Price 2015:124).

A sustainable intervention to improve student outcomes should carry with it the impetus to change teacher's attitudes and beliefs in order for effective change to take place. Sailors and Price (2015) also indicate a need to seriously interrogate the concept of quality teachers and the assumption that teachers are ready to implement the teaching strategies stipulated in the official curriculum without any sustained professional development activities.

Teacher change was developed mainly from a model presented by early theorists such as Guskey (2000). However, when the experienced teachers were analysed in this research, it showed a different result. This model suggests that the professional development goals for teachers should change in terms of their classroom practices, beliefs and attitudes, as well as from changes in student outcomes (Guskey 2000).

Changes in teacher's classroom practices

The EGRS provided the necessary opportunities to participate in deliberate and purposeful professional endeavours and to expect developmental goals to be fulfilled. This study is underpinned by the theory of change. However, it is not professional development that brings about teacher change, but the actual implementation that leads to change in teachers' practices, attitudes and beliefs.

One of the teachers indicated that:

'I started writing and reading lessons, which I did not do before. I tried to follow the training and implementing all the reading strategies according to how I was trained.' (Teacher 5, School C, teaching for 36 years)

For her, change in teacher practice was essential, as the EGRS intervention programme was the first training that she had received in Foundation Phase teaching. The instructional strategies were new to her, and she implemented them according to her own understanding. However, she reported little improvement in the learners' outcomes. This revealed that the change in practice must be accompanied by ongoing support and an ability to analyse what is working and what is not. This is critical in improving skills, as it enables an individual to adapt and make adjustments according to the needs of different learners and of the class as a whole. However, this kind of analysis, as a component of change, is not taught. Those teachers who have coaches valued the support and input they received and displayed more positive change in the classroom.

Change in teachers' beliefs and attitudes

Several studies show that teachers who saw improvements liked teaching more and believed that they had a greater influence on student learning outcomes (Bloom 1968; Guskey 1979, 1982, 2000; Miles & Huberman 1984). Similar changes did not occur where teachers did not see the improvements. One of the teachers commented:

'I received EGRS training twice. I learnt the group guided reading process, how to mark their books, checking and editing in the `writing process. I applied the rubrics and memos. I learnt a lot. I know my learners, working with them all the time (time on task) not sitting at tables. I see a big difference in class in terms of cursive writing. Learners like to work with the teacher, so that's what I do. There's more involvement. I need more training. I am confused on the reading strategies. I am still fumbling but applying it to the way I know it.' (Teacher 2, School A, teaching for eight years)

This teacher exuded warmth and positivity in her comments and was looking forward to the changes she was implementing. Being with her learners gave her satisfaction that motivated her to keep trying. She reflected on her practice and could see where her challenges lay. The positive reactions of her learners inspired her to change her attitude and beliefs. If the students' outcomes were more significant, these beliefs and attitude changes will be enhanced and sustained.

On the contrary, another teacher said:

'I found that the time is too short to implement the EGRS programme as I would have liked. I have a number of slow learners and I struggle to finish the work in the given time. The work accumulates and I cannot be finished by the time the spelling test is written on Friday.' (Teacher 3, School B, 2nd year teacher)

In the case of this teacher, the partial or incomplete implementation or enactment made deep changes in her; therefore, changes in attitudes and beliefs were unlikely. Her remarks indicated that she was not entirely convinced about possible changes in student outcome, and she doubted the sustainability of the changes in her attitudes and beliefs as a teacher.

This teacher struggled with the implementation of the programme because of time constraints. This problem with the time management caused negativity in her attitude towards the programme. She admitted that because of having 'slow learners' she struggled to finish the work in the given time. The EGRS programme does not allow for pacing of work according to the needs of individual learners.

However, in the case of the third teacher there was a glimmer of positivity as she had been trained in strategies that she was able to implement more successfully with her learners. She indicated that:

'… [T]he training helped me cater for children with different learning abilities. Before, I used only whole class teaching. I learnt the different reading strategies and reading attention. I only did choral reading before. I now try all the strategies as per lesson planning.' (Teacher 3, School B, 2nd year teacher)

In her case, changes had occurred because she saw some improvement as a result of catering for differing abilities. She was prompted to continue trying out new procedures for effective changes in her students. This indicates that it is imperative for reflection to take place and for teachers to see the change to make them more receptive to the change.

One of the findings concur with Porter and Brophy's study (1988) and emphasise that teachers need to be knowledgeable about their students, adapting instruction to their needs and anticipating misconceptions in their existing knowledge. Their recommendations are as follows:

-

Address higher as well as lower level cognitive objectives. It should not be assumed that learners from a lower socio-economic background should be provided with inferior or lower-level instruction.

-

Monitor students' understanding by offering regular and appropriate feedback.

-

Integrate their instruction with that in other subject areas.

-

Accept responsibility for student outcomes and use data to assess where teachers are not meeting expectations.

The curriculum design and implementation is not in consonance with the progressive critical thinking teacher and does not serve as a reflective practitioner teacher education model, which this programme requires. The curriculum, and especially the lesson plans of the EGRS, is overloaded and has not taken the context and language into account, leaving little time to focus on development of knowledge, understanding and skills that Foundation Phase teachers will need to help learners grasp and improve in their learning.

Causes of ineffective classroom practices

Ineffective classroom practices, as reiterated by Stoll and Fink (1994), occur for the following reasons:

-

inconsistent approaches to the curriculum and teaching

-

inconsistent expectations for different learners learning from low socio-economic backgrounds

-

low levels of teacher-student interactions

-

low levels of student involvement in their work

-

student perceptions of their teachers as not caring, unhelpful, under-appreciating the importance of learning and their work

-

more frequent use of negative criticisms and feedback.

Stoll and Fink (1994) make the point that, when dealing with learners from deprived socio-economic backgrounds and who are not meeting teaching objectives, the teacher must decide if she should slow down her pace of teaching, differentiating her methods of delivery to suit the learners' ability levels, or carry on teaching and allow the learners to catch up as she teaches. They also emphasise the necessity for supervising and communicating about routines and getting learners used to working independently. More training and support is desirable for sustainability of the pedagogy in a robust and beneficial way.

Early grade reading study training and change in teachers' practice

The teachers in the EGRS programme were unanimous in applauding the training they received and all of them developed their understanding of the teaching of reading to some extent. It changed their teaching practice by allowing them to move from the traditional approach they were familiar with (rote-learning and choral reading) to making use of reading strategies such as reading aloud, shared reading and group-guided reading.

They were not completely versed in these strategies and did not understand their cognitive and metacognitive aspects, and this led to a failure to implement the strategies effectively, but they managed to change their teaching styles. However, more interaction with learners is necessary in the enactment of lessons. The use of independent activities during group-guided reading and independent and silent reading is non-existent.

It was found that more experienced teachers used the traditional ways of teaching such as using rote and memorisation techniques.

Time on task: The more experienced teachers divided their teaching time in such a way that, by the time a period is over, they had covered the content.

Home-language use: The teachers emphasised the use of the Setswana language in their teaching, from the pronunciation of words to listening to other learners as they are reading.

Of the four schools that were visited, there were more similarities than differences in the teachers' teaching styles. It was a top-down style of teaching, with some level of stricter teaching that instilled an element of fear in the learners. This was indicated by the lack of engagement; the researchers were not sure if teachers were aware of this.

Overall, it was observed that teaching and learning did take place. Some of the teachers performed efficiently while others did not understand why they were teaching in the way they were trained. As for the novice teachers, very little teaching and learning took place, although they had a better command of the English language. One teacher spent the first 15-min teaching and the rest of the time moving around the classroom, not knowing what to do.

All the teachers' knowledge of levelled texts needed to be developed, such as an awareness of structure, language conventions, comprehension, subject knowledge demands and levels of meaning, as well as the ability to judge the suitability of a text for particular learners.

Another aspect that required attention was the development of comprehension strategies before, during and after group-guided reading. These are techniques to enhance meaning and understanding that the teachers did not employ.

Implications for educational interventions

This research has implications for educational interventions in literacy teaching in different literacy programmes. Various studies Barnett et al. (2008) have shown that, regardless of the language of instruction, children in literacy programmes which featured specific mediation of print knowledge and phonological awareness showed much greater gains in literacy and other language outcomes.

Additional research is required that tests the efficacy and effectiveness of specific curricula designed for children learning in an African language (Hammer, Scarpino & Davison 2011:130) and to successfully improve pedagogy to improve learner outcomes.

Implications for learning to read

Firstly, all children can learn to read, even if they have intellectual disabilities. However, their existing phonological, vocabulary and syntax deficits, as well as their cognitive skills, affect the extent to which they are likely to become fluent readers in the early stages of learning to read. Therefore, processes related to phonological awareness, as well as those related to vocabulary development, syntactic production and comprehension, should be part of the teacher's daily instructional practice.

Secondly, early acquisition of vocabulary follows a predictable pattern, and thus, the problem of expressive language deficit in children could be identified by teachers through proper assessment and should be taken into consideration in determining group-guided reading. Appropriate instruction should be provided to increase expressive language and work with delays that appear in the reading classroom. Thus, differentiated instruction and levelled reading materials can provide much-needed scaffolding for increasing vocabulary and reading repertoire.

Thirdly, reading consists of two broad categories of skills: decoding (recognising printed words) and comprehension (understanding the meaning of printed words). Teachers using the various reading strategies should be well versed in teaching both skills and be able to constantly and implicitly reinforce these skills in their reading lessons.

In addition:

-

Teachers should adopt a learner-centred approach and lucid teaching objectives, appropriate teaching strategies and resources to promote class interaction to enable students construct knowledge.

-

Teaching should stimulate thinking, develop students' potential and foster their learning ability. Appropriate values and attitudes are fostered in the process.

-

Teachers should extend student learning through providing life-wide learning opportunities and developing cognitive and metacognitive skills.

Conclusion

Learning from different teachers and commitments to different programmes helps us understand how teachers enact different tools provided to them during training. The EGRS has provided teachers with tools to change their practice. Although teachers have tried to do so, some are still to see changes in their students' outcomes. A positive outlook and some support in terms of their practice would further allow teachers to enhance their practice and make the gains they desire.

Acquisition of oral language and learning to read with meaning is affected by various factors, some of which are a focus on content, teachers' application of reading strategies in the classroom, opportunities for active learning and engagement of learners, coaching of teachers, a concerted effort to change teachers' classroom practices, a change in teachers' attitudes and beliefs and the global development of specific skills for learning the phonological, lexical and morpho-syntactic systems. More research will illuminate how these factors can be better explored and used in the enhancement of teacher practice and to improve the reading of learners in Foundation Phase.

Recommendations

Based on the findings of the study, the following recommendations can be made:

-

Ongoing training and teacher development should be provided.

-

The sustainability of a literacy programme such as the EGRS should be considered.

-

Teachers should participate in an ongoing community of practice (CoP) in cluster groups.

-

The coaching method should be made a part of the programme as it seems to be the most effective way of addressing the poor level of readings.

-

Teach students metacognitive strategies and give them opportunities to master them.

-

Teachers should be taught to reflect on their practice and to think critically about their own pedagogy and that of their colleagues. They should be allowed to observe each other teach and learn from each other.

Acknowledgements

The researchers would like to thank the EGRS project, Class Act and the Department of Education for the support they provided to carry out the research.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Authors' contributions

G.B.M. is the main author and B.F. is the co author of this article. The main author contributed to the writing of the article in full with the guidance in terms of the theoretical framework and final corrections made by the co author.

Funding information

Financial assistance for this study was provided by the EGRS project funds to carry out the research, use an interpreter, edit the article and pay for the publishing fee.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and not an official position of the institution or funder.

References

Afflerbach, P., Pearson, P.D. & Paris, S.G., 2008, 'Clarifying differences between reading skills and reading strategies', The Reading Teacher 61(5), 364-373. https://doi.org/10.1598/RT.61.5.1 [ Links ]

Altinok, N., 2013, Performance differences between subpopulations i n TIMSS, PIRLS, SACMEQ and PASEC, Background paper for EFA Global Monitoring Report 4.

Barnett, W.S., Jung, K., Yarosz, D.J., Thomas, J., Hornbeck, A., Stechuk, R. et al., 2008, 'Educational effects of the Tools of the Mind curriculum: A randomized trial', Early Childhood Research Quarterly 23(3), 299-313. [ Links ]

Bloom, B.S., 1968, 'Learning for mastery. Instruction and curriculum. Regional education laboratory for the Carolinas and Virginia, topical papers and reprints, number 1', Evaluation Comment 1(2), 12. [ Links ]

Braun, V. & Clarke, V., 2006, 'Using thematic analysis in psychology', Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [ Links ]

Cain, K. & Oakhill, J. (eds.), 2007, Children's comprehension problems in oral and written language, Guilford, New York, NY.

Catts, H.W., Fey, M.E., Zhang, X. & Tomblin, J.B., 2001, 'Estimating the risk of future reading difficulties in kindergarten children: A research-based model and its clinical implementation', Language, Speech and Hearing Services in Schools 32, 38-50. https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461(2001/004) [ Links ]

Cilliers, J., Fleisch, B., Prinsloo, C. & Taylor, S., 2019, 'How to improve teaching practice? An experimental comparison of centralized training and in-classroom coaching', Journal of Human Resources 55(3), 926-962. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.55.3.0618-9538R1 [ Links ]

Creswell, J.W., Hanson, W.E., Clark Plano, V.L. & Morales, A., 2007, 'Qualitative research designs: Selection and implementation', The counseling psychologist, 35(2), 236-264. [ Links ]

De Clercq, F. & Shalem, Y., 2015, 'Teacher knowledge and professional development', in M. Felix & P. Martin (eds.), Twenty years of education transformation in Gauteng 1994 to 2014, African Minds, Gauteng Department of Education, Pretoria.

Denzin, N. & Lincoln, Y., 2000, Handbook of qualitative research, Sage, London.

Denzin, N.K. & Lincoln, Y.S., 2005, 'Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research', in N.K. Denzin & Y.S. Lincoln (eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research, 3rd edn., pp. 1-32, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Ehri, L.C., 2003, Systematic phonics instruction: Findings of the national reading panel, viewed 12 July 2019, from http://www.standards.dfes.gov.uk/pdf/literacy/lehri_phonics.pdf.

Elmore, R.F. & Burney, D., 1997, Investing in teacher learning: Staff development and instructional improvement in Community School District# 2, New York City, National Commission on Teaching & America's Future, Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, NY.

Farver, J.A., Lonigan, C.J. & Eppe, S., 2009, 'Effective early literacy skill development for young Spanish-speaking English language learners: An experimental study of two methods', Child Development 80(3), 703-719. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01292.x [ Links ]

Fernald, A., Marchman, V.A. & Weisleder, A., 2013, 'SES differences in language processing skill and vocabulary are evident at 18 months', Developmental Science 16(2), 234-248. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12019 [ Links ]

Fielding, L., Kerr, N. & Rosier, P., 2007, Annual growth for all students, catch-up growth for those who are behind, The New Foundation Press, Kennewick, WA.

Fleisch B. & Schindler J., 2009, 'Gender repetition: school access, transitions and equity in the 'Birth-to-Twenty' cohort panel study in urban South Africa', Comp Educ. 45, 265-79. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050060902920955 [ Links ]

Foorman, B.R., Herrara, S., Petscher, Y., Mitchell, A. & Truckenmiller, A., 2015, 'The structure of oral language and reading and their relation to comprehension in Kindergarten through grade 2', Reading and Writing 28(5), 655-681. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-015-9544-5 [ Links ]

Goodman, K.S. & Gollasch, F.V., 1982, Language and literacy: The selected writings of Kenneth S. Goodman. Volume I: Process, theory, research, Routledge & Kegan Paul, Boston, MA.

Guskey, T.R. & Monsaas, J.A., 1979, 'Mastery learning: A model for academic success in urban junior colleges', Research in Higher Education 11(3), 263-274. [ Links ]

Guskey, T.R., 1982, 'Differences in teachers' perceptions of personal control of positive versus negative student learning outcomes', Contemporary Educational Psychology 7(1), 70-80. [ Links ]

Guskey, T.R., 1986, 'Staff Development and the Process of Teacher Change', Educational Researcher 15(5), 5-12. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X015005005 [ Links ]

Guskey, T.R., 2000, 'Grading policies that work against standards… and how to fix them', Nassp Bulletin 84(620), 20-29. [ Links ]

Guskey, T.R., 2001, 'Helping standards make the grade', Educational Leadership 59(1), 20. [ Links ]

Guskey, T.R., 2002, 'Professional development and teacher change', Teachers and Teaching 8(3), 381-391. https://doi.org/10.1080/135406002100000512 [ Links ]

Hammer, C.S., Scarpino, S. & Davison, M.D., 2011, 'Beginning with language: Spanish-English bilingual preschoolers' early literacy development', Handbook of Early Literacy Research 3, 118-135. [ Links ]

Hart, B. & Risley, T.R., 1995, Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children, Paul H. Brookes, Baltimore, MD.

Hofmeyr, J., 2016, International literature review on alternative teacher education pathways, Prepared for the zenex foundation, JET Education Services, Johannesburg.

Howie, S.J., Combrinck, C., Roux, K., Tshele, M., Mokoena, G.M. & McLeod Palane, N., 2017, Progress In International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) Literacy 2016 Progress in International Reading Literacy Study 2016: South African Children's Reading Literacy Achievement, Centre for Evaluation and Assessment, Pretoria.

Juel, C., Biancarosa, G., Coker, D. & Deffes, R., 2003, 'Walking with Rosie: A cautionary tale of early reading instruction', Educational Leadership 60(7), 12-18. [ Links ]

Kuzborska, I., 2011, 'Links between teachers' beliefs and practices and research on reading', Reading in a Foreign Lan guage 23(1). [ Links ]

Larson, K., 2004, The science of word recognition, Advanced Reading Technology, Microsoft Corporation.

Leedy, P.D. & Ormrod, J.E., 2005, Practical research: planning and design, Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ.

LeMahieu, P.G., 2011, What we need in education is more integrity (and less fidelity) of implementation, Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, Stanford, CA.

Leonard-Barton, D., 1990, 'A dual methodology for case studies: Synergistic use of a longitudinal single site with replicated multiple sites', Organization Science 1(3), 248-266. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1.3.248 [ Links ]

Mabuza, N., 2017, 'The experiences of parents with special needs children in terms of access, resources and support for their children at special needs schools', Doctoral dissertation, University of Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Miles, M.B. & Huberman, A.M., 1984, 'Drawing valid meaning from qualitative data: Toward a shared craft', Educational Researcher 13(5), 20-30. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X013005020 [ Links ]

Mowbray, C.T., Holter, M.C., Teague, G.B. & Bybee, D., 2003, 'Fidelity criteria: Development, measurement, and validation', American Journal of Evaluation 24(3), 315-340. [ Links ]

National Education Evaluation and Development Unit (NEEDU), 2013, NEEDU National report 2012: The state of literacy teaching and learning in the Foundation Phase, National Education Evaluation and Development Unit Posted, Pretoria.

O'Donnell, C.L., 2007, 'Fidelity of implementation to instructional strategies as a moderator of curriculum unit effectiveness in a large-scale middle school science quasi-experiment', The George Washington University, Washington, DC.

O'Donnell, C.L., 2008, 'Defining, conceptualizing, and measuring fidelity of implementation and its relationship to outcomes in K-12 curriculum intervention research', Review of Educational Research 78(1), 33-84. [ Links ]

Porter, A.C. & Brophy, J., 1988, 'Synthesis of research on good teaching: Insights from the work of the institute for research on teaching', Educational Leadership 45(8), 74-85. [ Links ]

Pressley, M., 2000, 'What should comprehension instruction be the instruction of?', in M.L. Kamil, P.B. Mosenthal, P.D. Pearson & R. Barr (eds.), Handbook of reading research, vol. 3, pp. 545-561, Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ.

Reddy, V., Zuze, T.L., Visser, M., Winnaar, L., Juan, A., Prinsloo, C.H., et al., 2015, Beyond benchmarks: What twenty years of TIMSS data tell us about South African education, HSRC Press, Pretoria.

Reynolds, M., Wheldall, K. & Madelaine, A., 2011, 'What recent reviews tell us about the efficacy of reading interventions for struggling readers in the early years of schooling', International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 58(3), 257-286. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2011.598406 [ Links ]

Rumelhart, D., 1980, 'Schemata: The building blocks of cognition', in R.J. Spiro, B.C. Bruce & W.F. Brewer (eds.), Theoretical issues in reading comprehension, Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ.

Rumelhart, D.E., Spiro, R.J., Bruce, B. & Brewer, W., 1980, Theoretical issues in reading comprehension, pp. 33-58.

Sailors, M. & Price, L., 2015, 'Support for the improvement of practices through intensive coaching (SIPIC): A model of coaching for improving reading instruction and reading achievement', Teaching and Teacher Education 45, 115-127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.09.008 [ Links ]

Snow, C.E., Burns, S.M. & Griffin, P., 1998, 'Predictors of success and failure in reading', in C.E. Snow, S.M. Burns & P. Griffin (eds.), Predicting Reading Difficulties in Young Children, pp. 100-133, National Academy Press, Washington, DC.

SACMEQ II, n.d., 'Visualization of research results on the quality of education', Southern and Eastern Africa Consortium for Monitoring Educational Quality viewed 1 June 2011, from http://www.sacmeq.org/?q=research-visualization

Spaull, N., 2013, 'Poverty & privilege: Primary school inequality in South Africa', International Journal of Educational Development 33(5), 436-447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2012.09.009 [ Links ]

Spaull, N., 2015, 'Examining oral reading fluency among rural grade 5 English Second Language (ESL) learners in South Africa: An analysis of NEEDU 2013', South African Journal of Childhood Education 5(2), 44-77. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v5i2.382 [ Links ]

Stoll, L. & Fink, D., 1994, 'School effectiveness and school improvement: Voices from the field', School Effectiveness and School Improvement 5(2), 149-177. https://doi.org/10.1080/0924345940050203 [ Links ]

Stuart, M., Stainthorp, R. & Snowling, M., 2008, 'Literacy as a complex activity: Deconstructing the simple view of reading', Literacy 42(2), 59-66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-4369.2008.00490.x [ Links ]

Taylor, N., 2014, NEEDU national report 2013: Teaching and learning in rural primary schools, Government Printer, Pretoria.

Taylor, N., 2016, 'Thinking, language and learning in initial teacher education', Perspectives in Education 34(1), 10-26. https://doi.org/10.18820/2519593X/pie.v34i1.2 [ Links ]

UNESCO, 2005, UN decade of education for sustainable development 2005 - 2014: The DESD at a glance, UNESCO, Paris.

United States National Institutes of Health, 2000, Report of the National Reading Panel: Teaching children to read. An evidence-based assessm ent of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction - Reports of the subgroups, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, United States Department of Health and Human Services.

Woermann, F.G., Jokeit, H., Luerding, R., Freitag, H., Schulz, R., Guertler, S. et al., 2003, 'Language lateralization by Wada test and fMRI in 100 patients with epilepsy', Neurology 61(5), 699-701. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.WNL.0000078815.03224.57 [ Links ]

Yin, R.K., 2008, Case study research: Design and methods, 4th edn., Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Zimmerman, B.J. & Schunk, D.H., 2001, 'Self-regulated learning and academic achievement: theoretical perspectives', in B.J. Zimmerman & D.H. Schunk (eds.), Self-regulated learning and academic achievement: Theoretical perspectives, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Routledge, Mahwah, NJ.

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Geeta Motilal

geeta.motilal@wits.ac.za

Received: 11 Sept. 2018

Accepted: 07 Mar. 2020

Published: 23 July 2020

1 . The triple cocktail programme of teaching reading is a reading intervention programme that provided teachers with lesson plans, reading materials and coaching, together with pedagogical training to teach learners reading.