Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Childhood Education

versão On-line ISSN 2223-7682

versão impressa ISSN 2223-7674

SAJCE vol.10 no.1 Johannesburg 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v10i1.717

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Pre-service teachers' perception of values education in the South African physical education curriculum

Charl J. RouxI; Nazreen DasooII

IDepartment of Sport and Movement Studies, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

IIDepartment of Education and Curriculum Studies, Faculty of Education, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Since the beginning of the new democratic era of 1994 in South Africa, human rights and values concerns have been placed on the forefront of educational research to respond to the needs of the South Africa's Constitution as well as the intentions of public school curricula. It is believed that qualified physical education teachers can address the fading of values and recession of morals in schools by promoting value-based education into their physical education lessons to provide a holistic approach to learning

AIM: This article aims to identify the values that pre-service teachers deem are important to be taught at school.

SETTING: The study was conducted in the Gauteng Province.

METHODS: A questionnaire was employed to collect quantitative data (close-ended questions) and qualitative data (open-ended questions) from all final year BEd physical education students (n = 68).

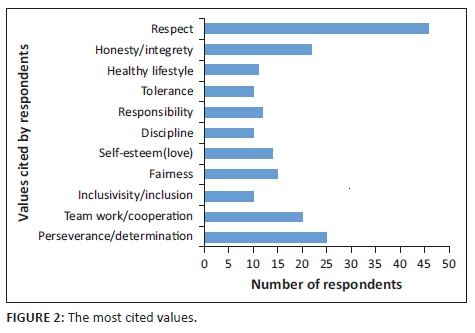

RESULTS: Sixty-eight values were identified: respect (n = 47), honesty/integrity (n = 23) and courage/perseverance/determination (n = 25) were ranked as the three values these teachers considered as important for inclusion in a physical education curriculum

CONCLUSION: These pre-service physical education teachers indicated that learners could learn core values and basic human rights in a conducive and safe learning environment by employing role-play, games and modelling as the main strategies to infuse values in their physical education lessons.

Keywords: values education; quality physical education; pre-service teachers; pre-service teacher training; curriculum development.

Introduction

Since the advent of industrialisation, a raised standard of living developed that resulted in the waning of values in most societies. This is fast becoming a common occurrence globally (Aneja 2014; Anil 2014). In South Africa, education developed from missionary, colonial and Eurocentric education that was mostly influenced by a western ideology (Roux 2009). This education system developed into four segregated school systems for black, mixed race, Indian and white people, supported by the institutionalisation of harsh apartheid policies from 1948 to 1994. However, following the inaugural ceremony of Nelson Mandela as the post-apartheid President of South Africa, on 10th May 1994, a new democratic country begun the process of social, political, economic and educational transformation aimed at developing a healthy egalitarian society (Lomofsky & Lazarus 2001). Yet, more than 20 years into democracy, traces of injustice and various forms of discrimination remain evident (Dasoo & Henning 2012; Roux & Janse van Rensburg 2017). Against this background human rights violation and especially human rights education have become eminent (Simmonds & Du Preez 2017). Given this scenario, Spacey (2017) has argued that the explicit development and teaching of applicable and appropriate values have become an urgent need. This is therefore necessary to address the recession of values from childhood to develop a well-rounded, democratic and humanistic personality.

This article explores the perceptions of pre-service physical education (PE) teachers specifically in South Africa. A common feature of the ever-changing world we live in is that the changes occur rapidly; this change is varied and very unpredictable. Urbanisation, globalisation and westernisation play an important role in this changing world (Anil 2014). Ongoing political, social and cultural changes and development have increased the necessity to acquire values that allow individuals to establish effective and efficient communication; this, in turn, has developed enduring solutions that conform to ethical rules (Hatipoğlu 2017). A plausible argument is that recent historical and technological developments may have also contributed to people turning away from enduring spiritual and human values. Parents, especially mothers, are primary educators at home, which is the first school where values are taught (Anil 2014). Parents are often pre-occupied with their careers such that the inculcation of values in children is largely left to day-care centres.

The scholarships of human rights and human rights education have increased exponentially since the 1970s (Simmonds & Du Preez 2017). Yet, although contemporary education focuses on learners to reach their full potential, children are more exposed to negative situations and matters on TV and mass media where various social ills, such as drugs, alcohol and gambling, are shown and cause instability in a rapidly growing world (Haljasorg & Lilleoja 2016). These TV programmes and public broadcasting media often have negative effects on moral development. This therefore could contribute to juvenile delinquency (Aneja 2014). Although the acquisition of knowledge, skills and attitudes is uniquely structured in different societies through informal and formal learning practices (Roux, Burnett & Hollander 2008), schools have an important role to play because most values are gained and shared at educational institutions.

Conceptual framework

Various prominent childhood development theories and models provide guidelines to understand and assist childhood development in a balanced way (Meier 2014). Examples of such theories and models are the social cultural theory of Vygotsky (1978) and, more recently, Bailey's human capital model (2015). The aim of the six Ministers of Physical Education and Sport (MINEPS) conferences that were held in Paris (1976); Moscow (1988); Punta del Este (1999); Athens (2004); Berlin (2013); Kazan (2017) are all aligned to the development aims of the Kazan Action Plan's implementation as an outcome of the MINEPS VI recommendations (UNESCO, 2017). Since MINEPS VI was held in Kazan, in the Russian Federation, this plan for the implementation of quality physical education was called the 'Kazan Action Plan'. All the above studies have provided frameworks for understanding children's development and learning towards their full potential and self-actualisation.

Schooling means learning, preparing and achieving, and PE provides the necessary content to address the holistic development of learners (Abels & Bridges 2015; Gallahue & Donnelly 2007). This takes place in a framework of human justice where the schools provide the context for developing a sense of community for active and responsible citizens (Talbot 2001).

In this article, values, values education and humanism are explored and defined; then the methods of inquiry are described, followed by a discussion of results. Lastly, without being too prescriptive, the article offers some recommendations.

Values and values education

Learners spend most of their daily lives at school, interacting with educators and peers in curricular as well as co-curricular activities with the aim of acquiring knowledge, various skills and to change attitude (Simonton, Garn & Solmon 2017). However, Jančiauskas (2011) has argued that there is a recession of values; it is a current global experience. This experience is generating instability that is becoming a growing phenomenon, even in South Africa. For this reason, it has become important to develop sets of values that address this recession from the very early stage of a child's life. It seems that during the development of the personality of a child, their self-consciousness and relationship between them and others in their environment need to be fostered (Jančiauskas 2011).

Values are a fluid concept with different interpretations (Solomons & Fataar 2011). They are cognitive constructs (Spacey 2017), moral beliefs (Hatipoğlu 2017) and according to Halstead and Taylor (2000):

[P]rinciples which are usually abstract, but [can] also … be a physical entity to which human beings attach worth and thus can act as general guides to behaviour and as standards by which particular actions are judged to be good or desirable. (p. 169)

Researchers are of the opinion that values may contribute to the formation of an individual's identity (Spacey 2017; Stidder 2017). Value education indexes institutions of education and activities by which learners appropriate values (Hatipoğlu 2017). Etherington (2013) and UNESCO (2010) believe that values for solid citizenry should be explicitly incorporated into educational curriculum.

Values education is viewed as educational activities employed to develop character and basic humanitarian values, such as caring, citizenship, courage, patience, perseverance, respect, responsibility, accountability, trustworthiness, justice, honesty, solidarity, tolerance and peace (Katilmiş 2017). Values education fosters and raises a generation for a liveable world. It aims to cultivate learners' comprehension of basic humanitarian values and solve ethically the challenges and social ills of the society to which they belong (Katilmiş 2017). As captured by the Positive Youth Development (PYD) framework, the development of a positive youth should include the learning of positive habits and the development of psychological elements and characteristics such as a sense of optimism and hope (Gould & Carson 2008). This may help them to cope and find joy at school and thereafter.

Values are a key focus of programmes where behaviour change is the desired outcome (Spacey 2017). Existing facts reveal an essential link between values education and academic excellence (Lovat 2017). In Nordic countries, values are derived from the core curricula and legislation aimed at early childhood schooling and well-being (Sigurdardottir & Einarsdottir 2016).

It is evident that educators who teach values choose how they infuse values, but this is also an area of concern and needs to be investigated (Haljasorg & Lilleoja 2016). According to the sociocultural theory, or the cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT) of Vygotsky (1978) and Engeström (1987), teachers often strictly adhere to the curriculum content and lack critical debate on social issues emanating from contextual realities within the school and community environment (Dasoo & Henning 2012).

Humanism and values

Although parents, most often the mothers, are identified as the first social agents or teachers and home is considered to be the first school, because of contemporary changes in family structures, the family is losing its essence of being a crucial social agent (Anil 2014). Hence, education is largely confined to formal schooling where teachers do not explore beyond the outcomes of a curriculum, which are mostly determined by the government (Anil 2014).

Humanism is delineated as warmness towards another human who is to be loved; it esteems human life, giving it the premier value (Ҫetin 2016). Cetin (2016) argues that human bonding based on human values should be the focus of educating young generations for the development of a mature, democratic and enlightened persona.

Following the South African democratic dispensation of 1994, values and human rights feature nationally in educational research. Issues of human rights and social justice have received attention (Dasoo & Henning 2012).

To develop a positive character, widely shared pivotal core values form the basis (Roux & Janse van Rensburg 2017). Values education should deliberately (Spacey 2017) and constantly form part of teacher's professional development (Solomons & Fataar 2011). However, important questions still to be asked are as follows:

-

Which values are important for young people to live well with a sense of humanity?

-

How can schools as social institutions and teachers as social agents contribute to the process of values education?

Teachers as social agents, according to Vygotsky (1986), can mediate values using a curriculum, where and when the curriculum is designed accordingly. They can also act as human mediators in the capacity of role models (Vygotsky 1986). However, Dasoo and Henning (2012) maintain that to prescribe certain values taught with a specific pedagogy undermines critical inclusive debate on values, especially in a multicultural and diverse society such as South Africa, which is also reflected in schools. Difference exists, on the one hand, in learners' knowledge of appropriate behaviour and, on the other hand, what they know about their actual behaviours. The ability to make decisions is core in the internationalisation of learners' ethical values.

There is consensus in literature that the development of active citizenship should be accompanied by a strong moral code (Solomons & Fataar 2011). Ramphele (2008:10) argues that South Africans are over and above challenged by the 'ghosts of the past' because of apartheid. However, they are also confronted with the 'nightmares of the present', namely, HIV and AIDS, unemployment, poverty, corruption and many other social ills. Solomons and Fataar (2011:5) also conclude that education, especially values education, is characterised by two dissimilar and yet similarly essential phases, namely, socialisation and critical individuation. Socialisation refers to a continuing process whereby values, norms, behaviour and social skills appreciated by a society are attained. Behaviour indexes a person's social values (Ҫetin 2016). Schools should, however, provide appropriate and conducive milieu for such socialisation amplified by 'critical individuation' - a process of not only provoking uncertainty, motivating creativity and fostering critical reflection towards challenges but also eliminating impediments imposed on the 'socialisation' processes (Solomans & Fataar 2011:12). Ethical values encourage learners to conduct themselves humanistically, yet these proper and grounded humanistic conducts emerge from practice. It is therefore not enough to react only to inappropriate behaviour during physical education lessons, but also to create teachable moments, where a scene is set to introduce and practise certain values (Spacey 2017). This can be employed by adapting the rules of games and modelling different situations (Spacey 2017). During such interventions learners should be praised for their good behaviour and also taught to embrace good behaviour from their peers - such as honesty, respect, good relationships between learners and also between learners and their teacher, obeying the rules, and team members as well as their opponents and to create a safe space for all.

Whilst addressing the lesson content that is infused with values in a context-specific learning situation based on the experimental learning theory of Kolb (1984), learners should be invited throughout the lesson to reflect, analyse and discuss situations with their peers (Bunting 2006; Kolb 1984; Spacey 2017). This appropriate behaviour should be taught directly. Learners should also be taught how to adapt humanistic behaviour in real-life situations: outside the PE class, on the playground and at home. The transferability has become a global need and initiative for schools to invest in moral regeneration.

Especially in South Africa, social class and racial divide present a huge challenge for teachers. Therefore, attention should be given to the values that teachers themselves find as necessary, based on a thorough situation and needs assessment, to teach their learners.

Physical education

Physical education is often equated with teaching of games and sports, with technique empowerment as the main aim (Dania, Stasinos & Naki 2018). Participation in sports, PE and other physical activities has been regarded as a way to reach personal and social development of its participants because of the positive conception society has developed around these initiatives regarding the ability to convene change in knowledge, skills and attitudes (Còméz-Marmòl et al. 2017). Yet, as a result of the high occurrence of anti-social, violent and unhealthy behaviour in and around sports and sports-related activities, mere participation is not fruitful (Còméz-Marmòl et al. 2017). Despite the fact that PE is a familiar concept in the lives of many, Stidder (2015) argues that the educational contributions of PE are often taken with doubt and uncertainty. Often sweeping claims are made that PE can entrench character-building qualities in the youth, combat crime, cure obesity, develop responsible citizens and lead to success in school examinations (Stidder 2015).

Katzenellenbogen (1999) said the following about PE:

The name 'Physical Education', implies that classes in PE are meant to be more than merely participating in various physical activities but rather focussing purposefully on educationally planned and presented learning experience, hence enabling learners to know what is of value concerning their movement culture for adulthood. (p. 85)

The core goal of PE is to develop physically erudite individuals who have the competence to move in many physical activities in different contexts that are developmentally healthy and holistic for a person (Liu et al. 2017). In doing so, this addresses physical, psychomotor, cognitive, social and affective developmental domains (Dyson 2014).

Based on the ethical theories of Kant, Aristotle and Plato, Surprenant (2014) argues that PE acclimatises the body to submit to the will, and therefore it is acknowledged as an essential requirement for the prospect of human virtue: 'by overcoming pain and discomfort in non-moral situations, an individual prepares [himself/herself] to respond appropriately [to] moral situations where responding to bodily inclinations [would] lead him/her away from virtue' (Surprenant 2014:535). Whilst participation in PE does not engender individual virtue, it at least forces both will and body to become indifferent to moral education. Physical education teaches learners a wide variety of fine and gross motor skills (CAPS 2011) or physical activity (Dyson 2014). It also develops positive attitudes and values for important and positive living in a changing society (CAPS 2011; Roux 2009; Roux & Janse van Rensburg 2017). Physical education is more than just a movement and physical activity (Dyson 2014); it is integral to the holistic development of a learner.

In spite of the robust rationale for physical education, the quality of PE programmes has declined drastically and hence seriously criticised globally (Dyson 2014; Stidder 2015). Although there are many barriers and challenges faced by many teachers to deliver quality physical education (QPE) (UNESCO 2015), the main concern in South Africa started when PE was removed from the curriculum, and later in 2005 was replaced with outcomes-based education, which was also later replaced by a curriculum and assessment policy statement (CAPS) document. In the latter curriculum, PE was re-introduced as a part of three other learning areas of a subject called Life Skills, in both 'foundation phase (Grade R-3)' and 'intermediate phase (Grades 2-6)'. In secondary schooling, PE forms a part of four other learning areas of the subject called Life Orientation, in both 'senior phase (Grades 7-9)' and 'further education and training (FET) phase (Grades 10-12)'.

Many higher education institutions in South Africa train students to become life skills or life orientation teachers. It is clear that PE teachers do not receive appropriate training to become qualified specialists in physical education (Cleophas 2014). A world-wide survey (Dyson 2014; Stidder 2015) has indicated a decline in the state and status of PE in many countries. Some issues that have contributed to the marginalisation of PE include (1) failure of teachers to articulate programme goals, (2) the Department of Basic Education (DBE) to hold teachers and programmes accountable, (3) teachers to act professionally and (4) educator programmes that equip them to answer to the needs of a fast changing society (France, Moosbrugger & Brockmeyer 2011). Indeed, school is a compelling agent and influencer where young learners are exposed to learning environment in which they feel comfortable and confident to develop positive attitudes towards the subject matter (Bailey, Cope & Parnell 2015). Therefore, in a conducive learning environment, with a language that attributes positive qualities towards people (Roux & Janse van Rensburg 2017), learners are to be encouraged through a more deliberate opportunity to have holistic development (Roux & Janse van Rensburg 2017; Spacey 2017). Physical education, if structured appropriately, could promote positive holistic development.

Methods

For this exploratory, descriptive and contextual design, a mixed-method approach was employed (Thomas, Nelson & Silverman 2011). The goal of this research was to examine the perceptions of pre-service PE teachers regarding the values they considered important to be infused into a PE curriculum for secondary schools in South Africa. A questionnaire with (1) demographical information and (2) five open-ended questions was used to collect qualitative and quantitative data (closed-ended questions) from final year BEd pre-service students at a university in the Gauteng province of South Africa. Informal interviews with students to elicit their experiences were conducted regarding their school experiences. We also had access to their reflective journals where they had recorded their perceptions and experiences gained during their stay in a school.

Participants

The questionnaire was applied to all (n = 68) final year BEd students (pre-service PE teachers) at a comprehensive public university in Gauteng, South Africa. This group comprised 31 male and 37 female students who have been trained in PE as one of their major subjects. At the time of this research, these participants were completing their final segment of school and teaching evaluation comprising 7 weeks of stay at schools they had freely chosen.

Data collection

A pilot study was conducted to determine logic and content validity before the commencement of data collection (Thomas et al. 2011). A week prior to the 7-week period at schools, the students were invited to complete a questionnaire. Respondents were informed beforehand that if they desire they could exit at any stage of the investigation.

In the demographical section of the questionnaire (Section A), the participants were asked to (1) identify the most important place(s) they have learnt values at and (2) list in sequence (1 = most important to 5 = least important) the five most important values according to them. In Section B, the following open-ended questions were posed:

-

What do you understand by values?

-

Why do you think values should be taught in schools?

-

How should we teach values in our physical education classes?

Data analysis

Quantitative data were processed using the Statistical Package of the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21.0. Atlas Ti 7 (2003) was used to code each question for the entire sample. Then the qualitative data were thematically analysed to determine patterns and themes that had emerged (Saldańa 2013). These multiple ways of triangulation contributed to reliability, validity and trustworthiness of investigation. Data sets were analysed until saturation was reached. To keep the identity of the participants anonymous, alphabets were used for their identification. The findings are discussed below.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Faculty of Education, University of Johannesburg. The ethical clearance number is SEM1 2018-012.

Results and discussions

The qualitative and quantitative data collected through the methods discussed above were analysed with the following findings. In Figure 1, participants have listed family (n = 38), school (n = 17) and community (n = 17) as the most likely places to have learnt values. It was interesting to note that as PE pre-service teachers they did not consider sports, sports organisations or clubs (n = 6) to be as important as family, school and community for imparting values. This could be because teachers who were responsible for teaching were not specialists and therefore did not clearly understand the educational value of physical education nor had the knowledge and skills to deliver quality PE programmes (Stidder 2015).

It is evident that although parents (Anil 2014) still play an important role in imparting values, schools and communities still have an essential function towards the holistic development of all learners, especially in the households where family structure has changed because of death or work responsibilities.

According to Bailey et al. (2015) and Spacey (2017), schools through quality PE classes could influence learners through values. Therefore, for values to be inculcated successfully, there is a need to define character-building qualities and develop responsible citizens (Etherington 2013) by fostering a strong relationship between family, school, religious organisations and community. Although parents, guardians and extended family (n = 44) were identified as the most crucial social agents to teach values (Anil 2014), teachers, schools (n = 17) and community are equally recognised as compelling social agents in this regard (Solomons & Fataar 2011; Spacey 2017; Vigotsky 1978).

Participants in the investigation identified 68 values that they considered important for including in a PE curriculum. This phenomenon is in agreement with the findings of Solomons and Fataar (2011), who argue that values are fluid concepts with different interpretations, and Thornberg and Oğuz (2013), who claim that educators often decide on the values necessary to be covered in a curriculum. Figure 2 illustrates 11 most important values (mentioned 10 times or more) for teaching purposes. Respect (n = 47), honesty/integrity (n = 23) and courage/perseverance/determination (n = 25) were ranked as the three most important value clusters that the student teachers considered important for inclusion in a PE curriculum. In a similar study by Dasoo (2010), 144 teachers were asked the same question: 'what are the most important values to be taught?', to which the teachers ranked 'respect' as the highest value to be taught. Thornberg and Oğuz (2013) found that both Swedish and Turkish teachers ranked the value of 'respect' as the most important value to be taught. Similarly, Willemse, Lunenberg and Korthagen (2008) found 'respect' as the highest ranked value.

As determined from informal interviews, journals as well as the open-ended questions of the questionnaire, pre-service PE teachers in this investigation considered the teaching of human values to be important; they mostly described values to be relational (Katilmiş 2017; UNESCO 2010), that is, values about how to treat others, respect for others, honesty, compassion, cooperation, fairness and care for someone other than yourself (Solomons & Fataar 2011; Spacey 2017). For example, 'respect' is the most important value that one should have. Examples of this included 'it's an important life value to have'; 'when learners are taught how to be accountable, they become honest when playing games on a field'; 'by being sensitive to the needs of others you are being compassionate'. Furthermore, values relating to teaching learners their self-worth also featured highly among the values mentioned by PE pre-service teachers. These included being responsible, having humility, taking pride in appearance and performance, and being reliable.

From the qualitative data, the following themes and sub-themes emerged.

Theme 1: Values as a concept

Sub-themes: A guide or set of rules of life; principles and standards reflecting good behaviour and morals; ethics to improve our identity, society and citizenship; life skills.

Participant R 'Values are principles deemed as important qualities and standards of an accepted behaviour.' (Final year BED student, Female, 20 years)

Participant Z 'Values education is about teaching standards of behaviour, morals and life skills to positively influence thinking, decision-making and actions in all aspects throughout life.' (Final BED student, Male, 21 years)

Participant AB 'Values education is personal principles and standards of behaviour, one's judgement of what is important to contribute towards a better society. With all the good values people can reach their highest potential.' (Final BED student, Male, 25 years)

Participant AAP 'It is a very important part of every day's life for every human being to inform thoughts and actions. It additionally helps us in developing and growing. We have personal values, moral values, religious values, and all these play an important role in our lives. Values also guide our behaviours at school and at home and are part of our personality and identity.' (Final BED student, Female, 24 years)

Participant AAW 'Your personal values are a set of characteristics, also norms you have learnt at home and mostly at school. You should apply them in your daily life. It should be a part of your personality.' (Final BED student, Female, 23 years)

The growing recession of values not only in South Africa but also as a global phenomenon is generating instability. That is why it has become important to develop sets of values from the very early stage of a child's life to address this recession. It is important that during the development of child's personality, their self-consciousness and relationship with others in their family, school and community must be fostered (Jančiauskas 2011). With these two themes, the participants provided reasons and practical ways of inducing values education.

Theme 2: Reasons for values education

Sub-themes: To develop guidelines and standards for a more cohesive society; to build character; to bridge diversity.

Participant A 'Due to lack of time at home to interact and learn social and life skills, because we live in a rushed world, where most parents work till late, we as teachers have to teach our learners the main values that can help them to cope in life.' (Final BED student, Female, 23 years)

Participant AQ 'Values are a positive guide in society and therefore provide some solutions for the challenges we currently face in our schools and communities.' (Final BED student, Male, 22 years)

Participant AW 'Learners should be challenged for their current life style, then they should be taught the responsibility to build a better society for a healthy co-existence of all in South Africa.' (Final BED student, Female, 22 years)

Participant AAW 'To build character and social skills to assist learners. Not all come from nourishing environments. Teaching values on how to assert behaviour and actions. Hence, for learners to learn and understand how to behave accordingly.' (Final BED student, Female, 23 years)

The findings of this study are in line with that of Katzenellenbogen (1999) and Còméz-Marmòl et al. (2017), concluding that participation in sports, PE and other physical activities has been regarded as a way to reach personal and social development. These studies also agree that active participation in playful physical activities could develop a positive conception of society (Gould & Carson 2008; Katilmiş 2017).

Theme 3: A practical way of inducing values education

Sub-themes: Explicit and/or inexplicit; role model; conducive learning environment; participation in small multicultural groups; holistic development; physical activity and games to have fun and interaction; create a teachable moment; teach specific value; reflect, repeat and apply in real-life situations.

Participant G 'Work rather in small groups that represent the multicultural society of the school, play games, interact, well-structured with opportunities for learning specific values such as fair play, honesty, friendship, cooperation and teamwork. Learners should also explain how they will apply these values at home.' (Final BED student, Male, 23 years)

Participant AA 'In all physical education and other practical situations and sports where 'play' and 'learning values can happen at the same time'. The teacher should be a role model by acting and demonstrating the values. During the activity, the teacher should stop the class and explain the situation and what the value is all about. All teachers should be responsible for teaching values.' (Final BED student, Female, 22 years)

Participant AD 'By addressing the child in a holistic way with emphasis on effective domain. Although physical education can teach values through practical situations demonstrating the values, the whole school should deliberately plan this as a strategy for everybody. The values, therefore, should be incorporated in all classes.' (Final BED student, Male, 29 years)

Participant AAA 'To create a positive and conducive environment to develop respect and to strive for self-actualisation.' (Final BED student, Female, 24 years)

Using game element (play) as an important strategy was mentioned by most of the PE in-service teachers for infusing values in classroom: 'incorporate values with physical activities with a game that they can play' and 'teach about trust when passing a ball to [a] team member'. Modelling of values was the second most cited strategy that could be used to infuse values (Roux & Janse van Rensburg 2017; Roux et al. 2008; Spacey 2017). In this study, PE teachers stated that 'teachers must physically display these values in themselves, they must model them'. Infusing values in a PE classroom was also seen as a deliberate pedagogy, implying a conscious attempt at infusion of values (Spacey 2017). For example, the participants of this study agreed with the literature who said 'teaching about values through classroom rules, and even when the teacher puts up posters depicting values and then discusses them'.

Conclusion

Physical education cannot be limited to merely physical activity, games and sports. Employing a learner-centred, value-driven programme in which the varied demands of school-going children, especially in multicultural institutions such as South African public schools, are addressed through a holistic approach, should be reiterated (Bailey et al. 2015; Dyson 2014). Learners should be taught deliberately (Spacey 2017) the core values that empower them with necessary knowledge, skills and attitude to cope in school, in their community and in a rapidly changing social, cultural and economic world. However, values education should not merely include universal values, but rather the educators should determine, develop and foster an appropriate set of values in collaboration with learners and their parents (Czyz & Toriola 2012). This should occur in a humanistic manner and in a safe and conducive environment, with a sincere and professional relationship between educators and learners.

As in other programmes and curricula, PE teachers should purposely develop programmes infused with the necessary values and skills of life (Spacey 2017). The outcomes and consequences should not only be clearly stated but also communicated to both the learners and parents. These sets of values should be practised and form part of everyday routine at school, on the sports field, at home and in community as a moral life style of enlightened citizens (Roux & Janse van Rensburg 2017; UNESCO 2010).

With an innovative experiential learning approach (Camiré, Trudel & Berbard 2013; France et al. 2011; Koh, Ong & Camiré 2016), a qualified PE teacher could deliver a quality PE programme (UNESCO 2015) by providing an opportunity to all learners to be successfully introduced to values education (Ҫetin 2016). This innovative way of teaching could enable learners and their parents to find again meaning in PE. The teaching of appropriate values could be seen as pivotal to South African PE and school sports programmes. The PE teacher should develop a culture of lifelong participation in physical activity and sports that not only inspire but also forge a healthy individual from a viewpoint of holistic development.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

Authors' contributions

Both authors worked on the literature review. C.J.R. did the data collection and N.D. did the interpretation thereof. Both authors did the final write-up.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

References

Abels, K.W. & Bridges, J., 2015, Teaching movement education: Foundations for active lifestyles, Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL.

Aneja, A., 2014, 'The importance of values education in the present education system and the role of the teacher', International Journal of Social Science and Humanities Research 2(3), 230-233. [ Links ]

Anil, V., 2014, 'Parent-teacher' partnership in strength and valued based education: Life skills module', Indian Journal of Health and Wellbeing 5(10), 1249-1251. [ Links ]

Bailey, R., Cope, E. & Parnell, D., 2015, 'Realising the benefits of sport and physical activity: The Human Capital Model', Retos 28, 147-154. [ Links ]

Camiré, M., Trudel, P. & Berbard, D., 2013, 'A case study of a high school sport programme designed to teach athletes life skills and values', The Sport Psychologist 27, 188-200. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.27.2.188 [ Links ]

CAPS Document, 2011, National curriculum statement; Curriculum and assessment policy statement in life orientation, Department of Basic Education, Pretoria.

Celikkaya, T. & Filoglu, S., 2014, 'Attitudes of social studies teachers towards value and values education', Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice 14(4), 1551-1556. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1045069.pdf. [ Links ]

Çetin, F., 2016, 'Determination of values education self-efficacy beliefs of prospective teachers', International Online Journal of Educational Science 8(4), 88-96. https://doi.org/10.15345/iojes.2016.04.008 [ Links ]

Cleophas, F., 2014, 'A historical-political perspective on physical education in South Africa during the period 1990-1999', South African Journal for Research in Sport, Physical Education and Recreation 36(1), 11-27. [ Links ]

Còméz-Marmòl, A., Martinez, B.J.S., Sànchez, E.D., Valero, A. & Gonzàlez-Villora, S., 2017, 'Personal and social responsibility development through sport participation in youth scholars', Journal of Physical Education and Sport 17(2), 775-782. [ Links ]

Czyz, S.H. & Toriola, A.L., 2012, 'Polish children's perception and understanding of physical education and sport', Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 31(1), 39-55. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.31.1.39 [ Links ]

Dania, A., Stasisnos, P. & Naki C., 2018, 'Proposal for a value-oriented physical education curriculum for secondary education', in S. Popović, B. Antala, D. Bjelica & J. Gardašević (eds.), Physical education in secondary school. Researches-best practice-situation, Faculty of Physical Education of University of Montenegro, Montenegrin Sports Academy and FIEP, Bratislava.

Dasoo, N., 2010, 'South African teachers' experience of values and values education', Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Dasoo, N. & Henning, E., 2012, 'South African teachers' initiation into values education: Following the script', Education as Change 16(1), 129-142. https://doi.org/10.1080/16823206.2012.692209 [ Links ]

Dyson, B., 2014, 'Quality physical education: A commentary on effective physical education teaching', Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 85(20), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2014.904155 [ Links ]

Engeström, Y., 1987, Learning by expanding: An activity-theoretical approach to developmental research, viewed 31 March 2009, from http://ichc.ucsd.edu/MCA/Paper/Engstrom/expanding/toc.htm.

Etherington, M., 2013, 'Values education: Why the teaching of values in schools is necessary, but not sufficient', Journal of Research on Christian Education 22(2), 189-210. https://doi.org/10.1080/10656219.2013.808973 [ Links ]

France, T.J., Moosbrugger, M. & Brockmeyer, G., 2011, 'Increasing the value of physical education in schools and communities', Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance 82(7), 48-51. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.2011.10598659 [ Links ]

Gallahue, D.L. & Donnelly, F.C., 2007, Developmental physical education for all children, 5th edn., Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL.

Gould, D. & Carson, S., 2008, 'Life skills development through sport: Current status and future directions', International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology 1(1), 58-78. https://doi.org/10.1080/17509840701834573 [ Links ]

Haljasorg, H. & Lilleoja, L., 2016, 'How could students become loyal citizens? Basic values, values education, and national attitudes among 10th-graders in Estonia', TRAMES 20(2), 99-114. https://doi.org/10.3176/tr.2016.2.01 [ Links ]

Hatipoğlu, R., 2017, 'The opinions of the principals about the effectiveness of values education and their suggestions about how to teach them', Multidisciplinary Academic Conference, 11 March 2017, pp. 1-17, MAC Prague Consulting.

Jančiauskas, R., 2011, 'Preconditions of young learners' humanistic education during physical education lessons', Sportas 2(81), 17-23. https://doi.org/10.33607/bjshs.v2i81.326 [ Links ]

Katilmiş, A., 2017, 'Values educatio n as perceived by social studies teachers in objective and practice dimensions', Educational Science: Theory and Practice 17, 1231-1254. [ Links ]

Katzenellenbogen, E.H., 1999, 'Educational dance in a Phys Ed curriculum', in L.O. Amusa, A.L. Toriola & I.U. Oneyewadume (eds.), Phys Ed and sport in Africa, pp. 85-120, LAP Publications, Ibadan.

Koh, K.T., Ong, S.W. & Camiré, M., 2016, 'Implementation of a values training programme in physical education and sport: Perspectives from teachers, coaches, students, and athletes', Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 21(3), 295-312. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2014.990369 [ Links ]

Kolb, D.A., 1984, Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Liu, J., Xiang, P., Lee, J. & Li, W., 2017, 'Developing physical literacy in K-12 physical education through achievement goal theory', Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 36, 292-302. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2017-0030 [ Links ]

Lomofsky, L. & Lazarus, S., 2001, 'South Africa: First steps in the development of an inclusive education system', Cambridge Journal of Education 31(3), 303-317. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057640120086585 [ Links ]

Lovat, T., 2017, 'Values education as good practice pedagogy: Evidence from Australian empirical research', Journal of Moral Education 46(1), 88-96. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2016.1268110 [ Links ]

Meier, C., 2014, 'Windows of Opportunity: Early Childhood Development Prospects in South Africa', Journal of Social Sciences 40(2), 159-168. [ Links ]

Ramphele, M., 2008, Laying ghosts to rest: Dilemmas of transformation in South Africa, NB Publishers, Cape Town.

Roux, C.J., 2009, 'Integrating indigenous knowledge into physical education for the multicultural classroom: A South African context', African Journal for Physical, Health Education Recreation and Dance 15(4), 283-593. https://doi.org/10.4314/ajpherd.v15i4.49545 [ Links ]

Roux, C.J., Burnett, C. & Hollander, W., 2008, 'Curriculum enrichment through indigenous Zulu games', South African Journal for Research in Sport, Physical Education and Recreation 30(1), 89-103. https://doi.org/10.4314/sajrs.v30i1.25985 [ Links ]

Roux, C.J. & Janse van Rensburg, N., 2017, 'The role of an adventure programme infused with Olympic values in teaching Olympism to university students', South African Journal for Research in Sport, Physical Education and Recreation (Special edition) 39(1-2), 63-77. [ Links ]

Saldańa, J., 2013, The coding manual for qualitative researchers, 2nd edn., Sage, London.

Sigurdardottir, I. & Einarsdottir, J., 2016, 'An action research study in Icelandic preschool: Developing consensus about values and values education', International Journal of Early Childhood 48(2), 161-177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-016-0161-5 [ Links ]

Simmonds, S. & Du Preez, P., 2017, 'Discourses shaping human rights education research in South Africa: future considerations', South African Journal of Higher Education 31(6), 9-24. [ Links ]

Simonton, K.L., Garn, A.C. & Solmon, M.A., 2017, 'Class-related emotions in secondary physical education: A control-value theory approach', Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 36(4), 409-418. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2016-0131 [ Links ]

Solomons, I. & Fataar, A., 2011, 'A conceptual exploring of values education in the context of schooling in South Africa', South African Journal of Education 13(2), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v31n2a482 [ Links ]

Spacey, G., 2017, 'Learning and teaching values through physical education', in G. Stidder & S. Hayes (eds.), The really useful physical education book: Learning and teaching across the 11-16 age range, 2nd edn., Routledge, London.

Stidder, G., 2015, Becoming a physical education teacher, Routledge, London.

Stidder, G., 2017, 'Evaluating the "A" list in Physical Education initial teacher training', Physical Education Matters 12(3), 50-56. [ Links ]

Surprenant, C.W., 2014, 'Physical education as prerequisite for the possibility of human virtue', Educational Philosophy and Theory 46(5), 527-535. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2013.779210 [ Links ]

Talbot, M., 2001, 'The case for physical education', in G. Doll-Tepper & D. Soretz (eds.), World Summit on physical education, pp. 15-36, ICSSPE, Berlin.

Thornberg, R. & Oğuz, E., 2013, 'Teachers' views on values education: A qualitative study in Sweden and Turkey', International Journal of Educational Research 59, 49-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2013.03.005 [ Links ]

Thomas, J.R., Nelson, J.K. & Silverman, S., 2011, Research Methods in Physical Activity, 6th edn., Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL.

Willemse, M., Lunenberg, M. & Korthagen, F., 2008, 'The moral aspects of teacher educators' practices', Journal of Moral Education 37(4), 445-466. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240802399269 [ Links ]

UNESCO, 2010, EFA Global Monitoring Report 2010: Reaching the marginalized, UNESCO, Paris.

UNESCO, 2015, Quality Physical Education (QPE). Guidelines for Policy-makers, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation, Paris.

Vygotsky, L.S., 1978, Mind in society: The development of higher psychological process, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Vygotsky, L.S., 1986, Thought and language, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Charl Roux

croux@uj.ac.za

Received: 12 Nov. 2018

Accepted: 24 Nov. 2019

Published: 11 Feb. 2020