Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Childhood Education

versão On-line ISSN 2223-7682

versão impressa ISSN 2223-7674

SAJCE vol.8 no.1 Johannesburg 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v8i1.525

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Strengthening early childhood teacher education towards a play-based pedagogical approach

Alta J. van AsI; Lorayne ExcellII

IMusic Education, Foundation Studies Division, Wits School of Education, South Africa

IIWits School of Education, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Music as one of the creative arts offers an ideal vehicle to implement alternative teaching and learning strategies, including the implementation of purposeful but playful pedagogies that are increasingly being acknowledged as the most appropriate way of teaching young children. However, within higher educational institutions, it is becoming more difficult to develop sufficient content knowledge and confidence in student teachers to teach playfully through music. Students being unaware of playful music strategies favour 'desk bound' methodologies.

AIM: This article explores a music intervention aimed to deepen students' understanding of and ability to teach playfully through music and reflects on a shift in students' understandings and perceptions in response to the intervention.

SETTING: This article reports on the first 2 years of a music intervention programme which was offered to second-year early childhood education students studying for their BEd degree

METHODS: The research design is both qualitative and quantitative in nature. It explores how students experience challenges with music education and to explain the nature of these challenges. We outline a music intervention programme designed to deepen student teachers' understanding, ability and confidence to teach playfully through music. We made use of questionnaires, interviews and observations to explore the success of this intervention programme.

RESULTS: These showed that students' were positive, showing that students deepened their insights and increased their confidence to teach playfully through music.

CONCLUSION: In conclusion, the authors show that well-considered music education offers a viable way to enhance a playful approach to teaching and learning in the early years.

Introduction

The creative arts offer innovative opportunities not only for study within the arts, but also as a catalyst for alternative playful pedagogies in a wide range of contexts. This is particularly true for early childhood education (ECE) where there is strong consensus that young children learn best through playful approaches towards teaching and learning (Moyles 2010; Riley 2007). There is increasing evidence that playful approaches should not only focus on how children learn but also on how teachers teach through play (Brown & Patte 2013; Wood 2009); in other words, how teachers adopt playful approaches towards teaching and learning.

Despite this heightened awareness about the value of play-based learning and teaching, young children are being increasingly immersed in more formal teaching programmes where the emphasis is on paper and pencil representations (Wits School of Education 2009; Wood 2009). Thus, play-based pedagogies are being increasingly marginalised. One way to counter this marginalisation is through the adoption of appropriate arts - and for the purpose of this article, music education methodologies which foreground playful pedagogies. These methodologies deepen the acquisition of academic skills and concepts, enhance the young child's imagination and creativity and, at the same time, embrace a playful pedagogy (Pound 2010; Wood 2009).

To teach successfully through music requires teachers to have insight into both music content and methodologies (Shulman & Shulman 2011) as this directly affects their future teaching behaviour (Van Dooren, Verschaffel & Onghena 2002). However, the authors suggest that student teachers in ECE programmes at higher education institutions (HEIs) are having less and less exposure to music education.

The reasons are twofold. Firstly, during informal discussions with student teachers, most reported that they had few or no meaningful music education lessons while at school. Secondly, within the South African context, changes to teacher education programmes at a national and university level have resulted in less time being allocated to methodological subjects such as the creative arts (DHET 2015). Darling-Hammond and Baratz-Snowden (2007) note that internationally traditional teacher preparation programmes are criticised for being excessively theoretical, having little connection with practice, offering fragmented courses, and lacking a clear conception of teaching.

Consequently, pre-service teachers are not sufficiently developing their pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) (Neiss 2005). They are not able to draw on their own schooling experiences for ideas for facilitating meaningful music-making experiences in the classroom and neither are teacher education curricula providing sufficient opportunities for students to hone their methodological strategies. These factors, we suggest, have eroded their confidence to engage in music-related activities. We, therefore, argue that music education and education through music within the South African context are becoming increasingly marginalised. Thus, we asked ourselves the following question: how could we provide student teachers with relevant music input to build their confidence and enable them to include appropriate music content in the early learning curriculum based on a playful pedagogical approach?

We concluded that a music intervention programme designed to deepen student understanding, ability and confidence to teach playfully through music was the answer. This article reports on the first 2 years of an intervention programme which was offered to second-year ECE students studying for their BEd degree. The article, therefore, explores the effect of the music intervention aimed to deepen students' understanding of and ability to teach playfully through music. Furthermore, it reflects on a shift in students' understandings and perceptions in response to the intervention.

The research component of the project was framed by the following questions:

-

Before the music intervention:

■ What was students' understanding of music and in what music-making endeavours had they participated?

■ How did they view the value of music for young children and their learning?

■ How competent and confident did students feel they were to incorporate music as a teaching strategy?

-

After the music intervention:

■ How had students' understanding of music shifted?

■ How did they now view the value of music for young children and their [children's] learning?

■ How did they now view their competence and confidence to incorporate music as a playful teaching strategy?

Why music and early learning?

Music is a natural and important part of young children's growth and development. Early interaction with music positively affects the quality of children's lives. Successful experiences in music help all children bond emotionally and intellectually with others through creative expression in song, rhythmic movement and listening experiences (National Association for Music Education [US] n.d.). Furthermore, music is a child's first patterning experience, a 'highly social, natural, developmentally appropriate way to engage even the youngest child in math learning' (Geist, Geist & Kuznik 2012:78). This is the case even when they do not recognise the presence of mathematics in the activities.

Early engagement with music sharpens the brain's early encoding of linguistic sound; thus, musical experiences in the early years can enhance the acquisition of language, which in turn positively influences reading ability (Hallam 2010). Focused music listening instruction can benefit listening comprehension for children learning a second language (Goh & Taib 2006). Register (2001) found that music input has a positive effect on both phonological and spelling skills and that music-enhanced teaching promotes children's print awareness and writing skills. Children who have mastered steady beat independence are better readers, more successful at mathematics and are less aggressive in physical contact with peers (Geist et al. 2012). Brown (2013) concludes that benefits of engagement in music include language development, spatio-temporal skills, concentration, memory recall, social competence and happiness (wellbeing).

In 2012, Brandt, Gebrian and Slevc published one of the most comprehensive studies to date on music and early language acquisition. In reviewing 255 studies, they proposed a new definition of music that would be consistent globally, across cultures and music genres, and is particularly appropriate and helpful in the context of our music intervention: 'Music is creative play with sound; it arises when sound meets human imagination' (Brandt et al. 2012:327). They conclude with describing the spoken language as a special type of music and note that the review of existing studies presents a 'compelling case that musical hearing and ability is essential to language acquisition' (Brandt et al. 2012). In light of the current global emphasis on early mathematics and literacy learning, it becomes unthinkable that teaching through music is not an integral part of ECE teaching and learning strategies.

A pedagogy of play

According to Wood (2009), ECE teachers appear to have little understanding of how to teach playfully, resulting in ECE programmes becoming more formal. One way to counter this 'formal creep' is to give teachers good insight into well-planned and rigorous play-based methodologies, which include music education. Wood (2009) refers to such strategies as a 'pedagogy of play', which she defines as:

The ways in which early childhood professionals make provision for play and playful approaches to learning and teaching, how they design play/learning environments, and all the pedagogical decisions, techniques and strategies they use to enhance learning and teaching through play. (p. 27)

This approach, underpinned by a socio-cultural perspective, recognises children as powerful players in their own learning. They are viewed as capable, competent and unique human beings who are able to make and co-construct meaning together with responsive adults such as the teacher, to develop increasingly complex forms of knowledge, skills and understanding (Fleer, Anning & Cullen 2009). Thus, the focus in ECE is shifting to teacher and child interacting through the adoption of playful but meaningful teaching strategies based on the children's interests.

Children's interests remain central to curriculum planning while the subject disciplines enrich and extend their learning. Co-construction requires that teachers, for example, find out more about content knowledge, know how to set out stimulating learning environments and make provision for playful approaches to learning and teaching (Jordan 2009). The teacher is not necessarily 'the expert'. Learning happens together with the children in ways that support holistic development and are culturally and contextually responsive to each child's circumstances. Furthermore, the activities, both child-initiated and teacher-guided, must be of sufficient intellectual challenge to guarantee optimal learning opportunities (Bennett, Wood & Rogers 1997). When these criteria are met, play is associated with the development of creative skills, which in turn 'fosters creativity of thought, imagination, strategies for problem solving and the development of divergent thinking ability' (Lester & Russell 2008:34).

Music education, which demands an insightful understanding of the discipline and an interactive approach with the children, becomes an important strategy to further playful approaches to teaching and learning in ECE. As Pramling-Samuelson and Asplund-Carlsson (2008) note, this approach demands an extremely high professional competence from teachers. And, as previously argued, student teachers do not have these competencies, and this poses a considerable challenge to teacher education in the ECE phase.

Addressing the challenges: Researching and describing a music intervention programme

Teachers teach as they were taught (Kagan 1992; Pajares 1992). As many have not experienced either playful or music teaching strategies, it is not surprising that Woods (2009) and Moyles (2010) cite increasing evidence that ECE teachers themselves do not know how to teach playfully. Consequently, it becomes more difficult for student teachers to incorporate playful methodologies involving music into their teaching strategies. To address these concerns, we explored a music intervention programme as a way of supporting student teachers to implement meaningful and playful music teaching strategies.

In 2013, we planned and developed a 7-week interactive music programme. This programme was rooted in the widely accepted and appraised pedagogies of Orff1,2 Dalcroze3 and Kodàly4. In the first year of the intervention, students were introduced to a variety of music concepts including beat, meter, duration, tempo, pitch, dynamics, form and mood. Each music session was a combination of carefully selected theoretical input and thoughtfully designed opportunities to put this theory into practice in an interactive way, incorporating playful learning strategies such as singing, exploring beat through example, different joyful dance movements, body percussion and percussion instruments. We adopted a playful experiential approach requiring students to firstly hear (live and recorded music); secondly do (singing, moving, playing instruments or body percussion); then see (engaging with visual representation of beat, rhythm and pitch) and lastly, based on observation and reflection, create (dance movements, rhythms, rhymes and simple children's songs. Vannatta-Hall (2010) notes that all available evidence suggests:

when teacher educators provide opportunities for students to create, perform, and respond to music, they are better positioned to provide meaningful, enriching musical experiences for their students. (p.38)

Responding to, performing and creating music were important aspects of our intervention programme. Further, from the outset the programme was continually informed and adapted by student responses. Together with the lecturers, students were encouraged to co-construct their knowledge and understandings of the music concepts through continual practical application: experimenting and creating new ways of expressing their understanding of each concept through movement, playing and singing. Thereafter, they would create new activities for children to experience the concept, and teaching aids to visually represent the essence of the concept. This included graphic notation of newly composed simple pentatonic melodies for rhymes and rhythm game cards. Students would play their rhythm compositions on a range of percussion instruments each student was required to design and make.

Together with the lecturers, students were encouraged to co-construct their knowledge and understandings of the music concepts through exploring music pedagogies in a playful way.

We continually stressed this playful approach. Just as young children are sensorimotor learners (Piaget 1997) who learn through active participation and exploration of their environment, so too do adults. A successful music programme for both children and adults should therefore incorporate visual, auditory, tactile and kinaesthetic strategies to provide vividly experiential opportunities for advancing music and non-music ability (Brown 2013). We propose that our music intervention, based on interactive participation and reflection, is such a programme.

After the first intervention, based on reflective consideration and student feedback, we resolved that 'less was more' and, in the second-year of the intervention (2014), focused on only three music concepts, namely beat, rhythm and pitch.

A great focus was placed on singing as this is the most important and assessable form of music-making for children (Kodàly, in Houlahan & Tacka 2008). Singing was both the most challenging and rewarding part of the intervention. Many adults have negative perceptions about their own singing voices and find singing embarrassing - usually because somewhere in their childhood they were told that they cannot sing. In the first intervention, some students were actually crying when they heard that they would be expected to sing. It was heartening to observe these students becoming more comfortable with their own voices. Increasing confidence allowed for more experiences and learning (often incidental) through singing traditional (representing the cultures in the group) and specially composed children's songs. Through dancing and instrumental or body percussion accompaniment to songs like Funga Alafia, SaobonamahSithole, Dumela and Mary had a little lamb, additional layers of music understanding such as pitch, mood, form and thoughtful interpretation of lyrics were incidentally experienced in lively and enjoyable ways. At the end of the 2013 intervention (first cycle in the research), it was particularly gratifying to see the same students participating in singing without angst in their practical presentations.

Once students had been familiarised with and had practically engaged with the music concepts, they were expected to consolidate their newly acquired skills and knowledge by designing their own music activities appropriate for young children. Activities had to include singing children's songs, storytelling through music, rhythm exercises and teaching one simple song. Students were expected to work in groups and to present these activities to their peers.

Guidelines were provided and specific activities were allocated to each group to prevent repetition. To build their levels of confidence, original student work was strongly encouraged. The process was carefully scaffolded, and lecturers were available for consultation throughout the process. Certain periods were assigned specifically to support the students in their planning process. During the presentations, students seemed pleasantly surprised by their own and peers' capabilities to develop and facilitate meaningful, experiential music activities. After each group presentation, through a process of collaborative reflection between the presenters, their peers and lecturers, a range of alternative activities were considered. This collaboration was a highlight in the programme. In the process all participants had the opportunity to experience and evaluate the efficacy of old and new activities. The approach of requiring students to reflect and then create their own movements and rhythms and rhymes after engagement with each music concept in the programme seemed to have been a constructive strategy.

The class unanimously decided to share their presentations with each other enabling all of them to increase their collection of music resources. These resources enabled students to increase their repertoire of teaching strategies and material. Students reported that this was extremely helpful during their teaching experience5 when they were expected to individually present at least two music activities or rings to the children.

The research process

The research design is informed by pragmatic knowledge claims where we were interested in determining numerical data and exploring the reasons behind the responses. Thus, this study was both quantitative and qualitative in nature. According to Creswell (2003), a pragmatic paradigm opens the door to multiple methods and different worldviews.

There were two reasons for adopting a mixed-method research design. Firstly, we wanted to verify our initial premise (based on our informal conversations with students) that most have not had any meaningful music-making experiences. This required the collection of numerical data through questionnaires. Secondly, there was a qualitative element. According to Merriam and Tisdell (2015), this would allow us insight into students' perceptions of music and teaching playfully through music. We believe that the insight we gained through these data allowed us to develop authentic strategies for building student levels of self-confidence and providing relevant support for their music-making activities. Thus, a dual approach provided us with the best understanding of our research problems (Braun & Clarke 2013).

We adopted a sequential process for data gathering beginning with quantitative data collection. Students were invited to complete a questionnaire at the commencement of the study in order to gather numerically related data. This process was repeated after the intervention. After the initial questionnaire was administered, we probed more deeply to better understand reasons for the initial responses. We made use of open-ended questionnaires, observations which were detailed through field notes and video recording (Bogdan & Biklen 2007). In addition, we obtained data though student reflections on their own and each other's activities, informal conversations with students during and after the intervention, as well as observations during their teaching experience.

The sample comprised 71 students. In 2013, we had a 68% compliance rate and a 100% in 2014. Ethical clearance was obtained, and protocols were observed throughout the project.

Data were thematically coded into four themes. These themes, which are presented in the findings, were determined by the literature review, responses given to the questionnaires, observations, video footage and reflections on student presentations (Rule & John 2010). Quantitative data are presented in graphs, showing the percentage of students for each criterion which was specifically determined for the four themes. In each graph, the number of students for each criterion is presented as percentage on the Y axis. Each criterion is shown as a bar graph on the X axis. Pre- and post-course responses to the questionnaires were analysed for the 2013 and 2014 interventions. Individual student responses between pre- and post-intervention questionnaires were compared. After the second intervention in 2014, we also compared responses between the two years. We verified the results obtained from the questionnaires through observations, transcribed video footages and reflections.

The data obtained from the questionnaires enabled us to determine if there had been any improved understandings of the benefits and value of music in the early years and if students thought their confidence to present music activities had increased. The video recordings clarified the extent to which students had developed their ability to incorporate music playfully into their teacher-guided activities. The initial findings were further corroborated through reflections, informal conversations and observations during students' practical teaching experience.

Ethical consideration

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Wits School of Education Ethics Committee (number 2013ECE099S) and protocols were observed throughout the project.

Findings and discussion of findings

We present the findings and relevant discussions for each of the four themes.

Theme 1: Students and their interaction or engagement with music

We divided this theme into three subcategories. These were students':

-

enjoyment of music

-

participation in music

-

understanding of music.

The findings for the pre-course questionnaires were remarkably similar in both groups (2013 and 2014) for these three subcategories.

Enjoyment of music

All students mentioned that they enjoyed music and vacillated between absolutely loving it to liking it. No student disliked music. There was no significant change in post-course findings in relation to this category.

Participation in music

Just over two-thirds of the group had had some personal music experiences during their school years. School music experiences included singing in the school choir and/or playing in a school marimba band (15). A number of students had taken private lessons in piano (11), keyboard (1), drums (3), guitar (2) and clarinet (2) (see Figure 1). Most students stressed that this input happened during primary school; it was not memorable and they have had little, if any, music experiences since then. This lack of music experience, we argue, reinforced the lack of confidence that they demonstrated when commencing the intervention (questionnaire and lecturer observations).

In addition to their school experience, the majority of students indicated that they currently continue to interact with music in at least two or three different ways as shown in Figure 2. The majority listen and sing to music. Some dance to music. A few said that they play a musical instrument; drums, guitar, piano and clarinet were mentioned. The playing of instruments was closely linked with their personal experiences of music (see theme 2). A small number (less than 10%) said they do not participate in any music activities. Further probing revealed that these were Muslim students, who for religious reasons could not actively participate in music activities.

Post-questionnaire responses indicate a small percentage increase in extracurricular music activity. For example, two students said they now sing in a church choir, which indicates an increased confidence in their singing voice (see theme 3). We would also argue that the music course encouraged students to start realising the value of music, both for learning and emotional and social wellbeing as confirmed by Brown (2013). Evidence to support this claim comes from post-course questionnaires and informal conversations during the intervention and teaching experience.

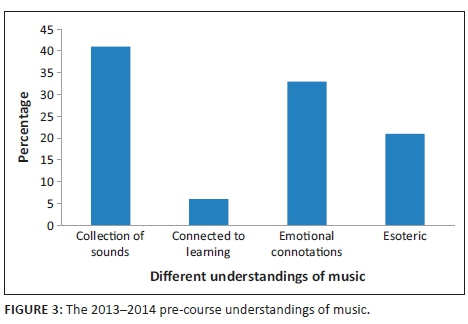

Understandings of music

As Figure 3 shows pre-course responses for both groups were similar. For example, in the pre-course questionnaire, students described their understanding of music as a collection of sounds but did not expand on this general understanding. A few mentioned that it was related to expressions of feelings and emotions and that 'it makes you feel happy'. Some alluded to more esoteric understandings of music. Responses included 'It is part of who I am' and 'Music is life', with no further explanation provided. These responses accentuate the importance of music in the personal lives of many student teachers. It is paradoxical that while music apparently plays an important role in the personal lives of these students, it was virtually absent from their professional practice (see theme 2).

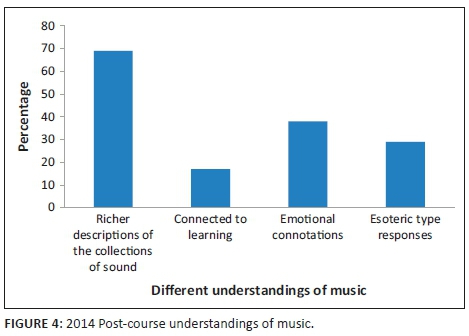

Post-course responses for the 2013 group demonstrated no significant shift. Students still gave fairly general and simplistic responses. However, we found a small but significant shift in post-course responses of the 2014 cohort, which demonstrated more insightful understandings of music. They gave a combination of responses, indicating that the 2014 cohort appeared to have gained a deeper understanding of the complexities of music as shown in Figure 4.

For example, students expanded on their understanding of music being a collection of sounds; the sounds now contained concepts of music such as beat, pitch and rhythm. This improved understanding is captured in the following comments which relate to the three concepts taught. One mentioned … 'different sounds that come together to form a melody and a coherent sound', and another mentioned 'sounds with beat, pitch and rhythm'. Students also expanded on how music made them feel as an expression of emotion, '… beat and rhythm that inspires moods'; and 'beat you move to'; and 'rhythm, beat and pitch that you feel in your body and soul'.

Students also referred to the more esoteric nature of music. For example, 'Music is within us all'; 'It is that intrinsic need to move and express oneself'; 'It is beauty that can be felt regardless of what you do or who you are'; 'Music is something you do see and feel … use it to express yourself;' and 'Music is a fun way in which to escape and deal with realities'. This enriched understanding of music can be attributed, we argue, to the more focused and structured course given to this cohort. Less proved to be more. By focusing on only three concepts, we were able to adopt an intensive experiential, hands-on approach. This approach enabled students to identify and relate more closely to music knowledge - the theoretical underpinnings of what comprises an appropriate music education (Vannatta-Hall 2010) and to PCK - the practical realisation - (Neiss 2005). Together, we co-constructed knowledge and shared experiences framed by a pedagogy of play (Wood 2009). Over time, increasing student participation contributed to their expanded understanding of music. Students realised that we did not expect them to be 'experts' but to work collaboratively together to extend their music skills and teaching strategies. Lecturer observations also revealed that over time students began to establish good working relationships with each other, a testament to the holistic value of music education (Alsup 2005).

Theme 2: Students' views on sufficient musical exposure for young children

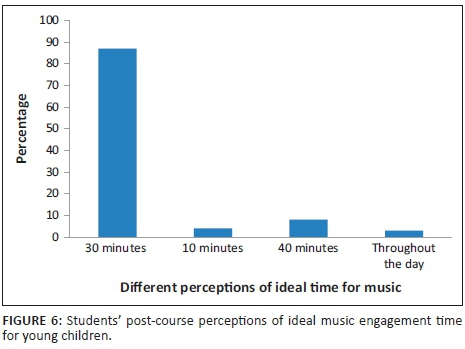

Almost all of the students agreed that children enjoy music and would benefit from having planned classroom music experiences. Figure 5 shows the pre-course responses. Noticeably, despite agreeing that children would benefit from planned music experiences the majority of students did not think that children required much music input during the school day. Only one student indicated that it was ideal to include music throughout the learning day. We would argue that this lack of insight relates to Jordan's (2009) claim that most teachers have a poor understanding of playful pedagogies and are not able to successfully implement play-based learning activities, especially those related to music activities (Pound 2010).

Nearly half of the students said that they included music in their personal teaching, but this was mainly singing and nursery rhymes. Observations showed that their repertoire was very limited. A small number of students mentioned that they had never thought of including music activities in their teaching. A typical comment from this group was, 'no - have not thought of it until now'.

As Figure 6 shows, the post-course responses revealed a small but significant shift in how students viewed children's participation in music. All students now thought children needed exposure to music, indicating some acceptance of the value of learning through music (Hallam 2010). In the pre-course questionnaire, one student stated that music activities should be offered throughout the day but then post-course admitted she only offered music activities sometimes. What had led, we asked ourselves, to this disjuncture between action and belief? Could it possibly be attributed to a lack of confidence to which she readily admitted during her teaching experience? Students' lack of confidence to teach music is well documented in the literature (Russel-Bowie 2012) and is captured in theme 3.

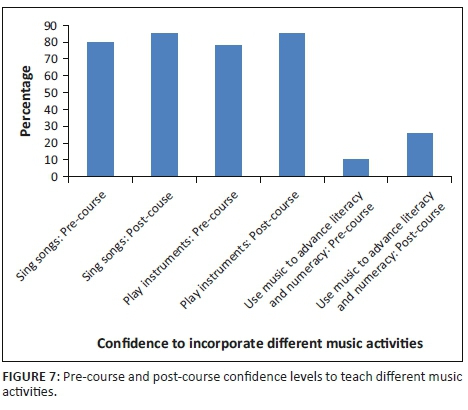

Theme 3: Students' confidence to offer music activities

Figure 7 presents the pre- and post-course confidence levels to teach music and the extent to which students would incorporate music activities. It is evident that the majority admitted to having little or no confidence to teach music. However, they agreed that if they knew more about music, they would endeavour to offer it during the school day. The students who said they would not offer music were Muslim students who had expressed their discomfort with music based on their faith. Music is a highly contentious issue in Islam (Szego 2005:199). But they admitted to also lacking confidence.

Figure 7 shows that most students admitted to having learnt something during the intervention programme and the majority expressed a growth in their confidence level. These confidence levels grew slowly, we suggest, because of the experiential nature of the course. During their teaching experience (TE), we observed many students beginning to incorporate appropriate music activities into their planned teaching strategies and use music to enrich incidental teaching moments. For example, they would introduce toilet routine with a song and encourage children to sing while tidying up. All these students acknowledged the value of music and how important it is to incorporate it into their teaching activities. Observations during TE revealed that even the Muslim students began to use music as a teaching tool. In fact, one student at a Muslim preschool made use of structured music rings as well as incidental music activities during the Holy month of Ramadan. When asked why, she replied:

'music is a fun and exciting way of teaching children many different concepts'. (Observation, female ECD 11 2013 student)

Typical post-intervention comments:

'At the start I had no music knowledge and did not know how to teach it; now I can see how fun and exciting it is to teach through music.' (Post questionnaire response, female ECD 11 2013 student)

and :

'It is actually easy to learn and fun to teach'. (Post questionnaire female ECD 11 2014 student)

But perhaps the best indication of increasing confidence levels, and indeed during TE, is this remark:

'First day-eish this is difficult but now hell I can do this'. (TE interview, female, ECD 11 2013 student)

Those students who had been involved in music during their school days mentioned that the course bolstered their confidence and helped them to more comfortably use what had been learnt during primary school. For example:

'I feel more able to use piano in my teaching; I can teach basic music and teach children to enjoy music' (Post questionnaire, female, ECD 11 2014 student)

and:

'Before the course could play music but had no idea how to teach children, now I feel much more confident'. (Post questionnaire, female, ECD 11 2014 student)

Pointing to an increase in confidence and basic music knowledge, a more common yet welcome response is reflected in these sentiments:

'I am not so scared of making a fool of myself.' (Post questionnaire, female ECD 11 2013 student)

'I now have some idea of what to do in the classroom.' (Post questionnaire, female ECD 11 2014 student)

Vannatta-Hall (2010) notes that all available evidence 'suggests that when teacher educators provide opportunities for students to create, perform, and respond to music, they are better positioned to provide meaningful, enriching musical experiences for their students'. We attribute the increase in confidence to the generous opportunities provided for creating, performing and responding in the intervention programme. Their increasing confidence was supported by the experience of co-constructing music activities with the lecturers. This was consolidated through methodologies that allowed them to experience the concepts of music over and over again (Hallam 2010). Our focus was on playful teaching and learning (Wood 2009) which deepened students' PCK through collaborative interactions (Shulman & Schulman 2011) and enhanced feelings of wellbeing (Brown 2013). As one commented:

'I have learnt many things that my voice can do and can create fabulous songs out of everyday words, phrases etc.' (Post questionnaire, female ECD 11 2014 student),

reinforcing the assertion that if one were to attempt to express the essence of Kodàly's education principles in one word, it could only be - singing (Houlahan & Tacka 2008).

However, despite acknowledging an increase in confidence and testifying to increased learning, some said they still felt nervous and a number of students said they would like more music input. They wanted examples of 'music rings' and wanted to learn many more songs. One student acknowledged that she was still not sure how to teach music:

'I think I have not learned much but do like the songs I was taught … I have some idea'. (TE interview, female ECD 11 2013 student)

Another student admitted:

'I'm more confident but still do not want to teach music - not my interest; I am not musically talented'. (Post questionnaire. female ECD 11 2013 student)

This remark speaks, we think, more to a lack of confidence than to a lack of interest or talent. We believe that over time with more input their confidence and professional teacher identity will grow. In part, we attributed their hesitance to a lack of PCK. PCK takes time to root (Shulman & Schulman 2011) and if appropriate support is given, we suggest that most students will become sufficiently confident to teach using playful music methodologies.

Theme 4: Incorporating music as a teaching strategy

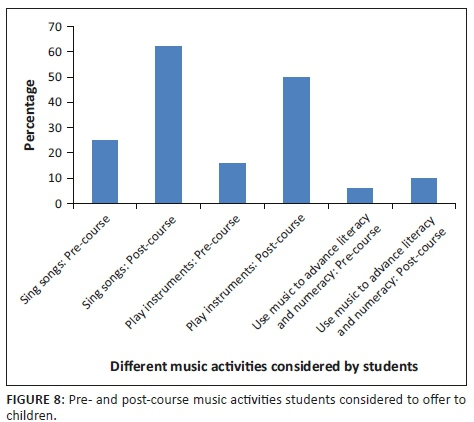

Figure 8 shows a comparison between pre- and post-course responses for both cohorts. Post-course, students were increasingly willing to offer more and a greater variety of music activities to children. Additional activities included the use of music in a school concert; specific music rings during teacher-guided activities; facilitating other activities such as visual arts and drama through music and making links between music and theme discussions as a way of gaining and keeping children's attention. Mention was also made of using music as an incidental teaching strategy such as 'at the beginning of the day', and as a 'positive discipline strategy'. We observed that the majority of students began to implement many of these strategies during their TE.

We posit that through this intervention students have still retained the fun image but have begun to deepen their pedagogical insights, sharpened their PCK (Neiss 2005) and realised the value of playful teaching and learning (Wood 2009) through primarily using the human voice (Houlahan & Tacka 2008). An additional finding was that they also made stronger links between music and mathematics and language learning, thus showing a deepening understanding of the value of music in ECE. Students remarked:

'I will try to incorporate music into learning concepts, e.g. shapes, colour and number.' (Post questionnaire, female, ECD 11 2014, student)

and:

'to include music in more subjects.' (Post questionnaire, female, ECD 11, 2013, student)

There was a greater realisation that music is an excellent way to encourage children to develop listening skills. Students referred to some of the activities such as percussion playing that were shared with them during the music course (post-course questionnaire). We viewed these findings as a positive shift from pre-course responses where music was seen as a fun activity for children but not as a usable teaching strategy. Our findings, in fact, suggest that post-course students had begun to deepen their theoretical understanding of the value of music in ECE and to demonstrate an increased competence to teach playfully through music.

Conclusion

We would argue that well-considered music education input, which is both interactive and innovative, offers a viable way to enhancing a playful approach to teaching and learning in the early years. Despite the numerous constraints and challenges that exist in current ECE teacher education programmes, a short, theoretically sound music intervention, which offers experiential learning opportunities that are culturally and contextually sensitive, can enhance students' perceptions of teaching and teaching methodologies. Although students initially displayed apprehension and reluctance to participate in music activities, they gradually relaxed, and within the span of 7 weeks, there was a notable shift in their confidence and competence. We acknowledge that developing proficiency in music-making and teaching takes time and requires ongoing support; we pose that an intervention such as this acts as a first but important step in developing ECE teachers' proficiency to engage children joyfully through a sound pedagogy of play.

Seemingly once students have been exposed to alternative music teaching practices, they appear to be willing to embark upon a journey of continuous developing. Such willingness was aptly captured by a student who commented:

'Practice makes perfect!' (Post questionnaire, female, ECD 11, 2014, student)

In so doing, she reiterated in a playful, colourful way (see Figure 9) - a tuneful ditty they had been taught: the beat, the beat, the beat is in my feet.

It seems that the music intervention programme proffered students the opportunity to experience music as 'creative play with sound [that] arises when sound meets human imagination' (Brandt et al. 2012). We sincerely wish for them to keep teaching to a constant music beat.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

Both A.J.v.A and L.E. contributed equally to the wrting of this article.

References

Alsup, J., 2005, Teacher identity discourses: Negotiating personal and professional spaces, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc, Mahwah, NJ.

Bennett, N., Wood, E. & Rogers, S., 1997, Teaching through play: Reception teachers' theories and practice, Open University Press, Buckingham.

Bogdan, R.C. & Biklen, S.C., 2007, Qualitative research in education. An introduction to theory and methods, Pearson, New York.

Brandt, A., Gebrian, G. & Slevc, L.R., 2012, 'Music and early language acquisition', Frontiers in Psychology 3(327), 1-17, viewed 30 April 2016, from http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00327/full [ Links ]

Braun, V. & Clark, V., 2013, Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners, Sage, London.

Brown, F. & Patte, M., 2013, Rethinking children's play, Bloomsbury, London.

Brown, L.L., 2013, The benefits of music education, viewed 21 December 2014, from http://www.pbs.org/parents/education/music-arts/the-benefits-of-music-education/

Creswell, J.W., 2003, Research design. Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Dalcroze Society of America, n.d., What is Dalcroze?, viewed 19 November 2015, from http://www.dalcrozeusa.org/about-us/history

Darling-Hammond, L. & Baratz-Snowden, J., 2007, 'A good teacher in very classroom', Educational Horizons 85(2), 111-132. [ Links ]

Department of Higher Education and Training, 2015, Minimum requirements for teacher education qualifications, Pretoria, viewed 30 November 2015, from http://www.dhet.gov.za/Teacher%20Education/National%20Qualification s%20Framework%20Act%2067_2008%20Revised%20Policy%20for %20Teacher%20Education%20Quilifications.pdf

Estrella, E., n.d., The Orff approach, viewed 19 November 2015, from http://musiced.about.com/od/lessonplans/tp/orffmethod.htm/

Fleer, M., Anning, A. & Cullen, J., 2009, 'A framework for conceptualising early childhood education', in A. Anning, J. Cullen & M. Fleer (eds.), Early childhood education. Society and culture, pp. 187-204, Sage, London.

Geist, K., Geist, E.A. & Kuznik, K., 2012, 'The patterns of music: Young children learning mathematics through beat, rhythm, and melody', Young Children 67(1), 74-79. [ Links ]

Goh, C. & Taib, Y., 2006, 'Metacognitive instruction in listening for young learners', ELT Journal 60(3), 222-232. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccl002 [ Links ]

Hallam, S., 2010, 'The power of music: Its impact on the intellectual, social and personal development of children and young people', International Journal of Music Education 28(3), 269-288. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761410370658 [ Links ]

Houlahan, M. & Tacka, P., 2008, Kodály today: A cognitive approach to elementary music education, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Jordan, B., 2009, 'Scaffolding learning and co-construction of understanding', in A. Anning, J. Cullen & M. Fleer (eds.), Early childhood education: Society and culture, pp. 40-52, Sage, London.

Kagan, D., 1992, 'Implications of research on teacher belief', Educational psychologist 27(1), 69-90. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep2701_6 [ Links ]

Lester, S. & Russell, W., 2008, Play for a change: Play, policy and practice. A review of contemporary perspectives, National Children's Bureau, London.

Merriam, S.B. & Tisdell, E.J., 2015, Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, NJ.

Moyles, J., 2010, The excellence of play, Open University Press, Berkshire.

National Association for Music Education (US), n.d., Early childhood education, viewed 15 May 2016, form http://www.nafme.org/about/position-statements/early-childhood-education-position-statement/early-childhood-education/

Neiss, M.L., 2005, 'Preparing teachers to teach science and mathematics with technology: Developing a technology pedagogical content knowledge', Teaching and Teacher Education 21, 509-523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2005.03.006 [ Links ]

Orpheus Academy of Music, n.d., What is the Kodaly method?, viewed 19 November 2014, form http://www.orpheusacademy.com/kodaly/

Pajares, M.F., 1992, 'Teachers' beliefs and educational research; Cleaning up a messy construct', Review of Educational Research 62(3), 307-332. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543062003307 [ Links ]

Piaget, J., 1997, 'Development and learning', in M. Gawerain & M. Cole (eds.), Readings on the development of children, pp. 20-28, W.H. Freeman and Company, New York.

Pound, L., 2010, 'Playing music', in J. Moyles (ed.), The excellence of play, pp. 139-153, Open University Press, Buckingham.

Pramling- Samuelsson, I. & Asplund-Carlsson, M., 2008, 'The playing learning child: Towards a pedagogy of early childhood', Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 52(6), 623-641. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313830802497265 [ Links ]

Register, D., 2001, 'The effects of an early intervention music curriculum on prereading/writing', Journal of Music Therapy 38(3), 239-248. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/38.3.239 [ Links ]

Riley, J., 2007, Learning in the early years, Paul Chapman, London.

Rule, P. & John, V., 2010, Your guide to case study research, Van Schaik, Pretoria.

Russel-Bowie, D.E., 2012, 'Developing preservice primary teachers' confidence and competence in arts |education using principles of authentic learning', Australian Journal of Teacher Education 37(1), 60-74. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2012v37n1.2 [ Links ]

Shulman, L.S. & Schulman, J.H., 2011, 'How and what teachers learn: A shifting perspective', Journal of Curriculum Studies 36(2), 257-271. https://doi.org/10.1080/0022027032000148298 [ Links ]

Szego, C.K., 2005, 'Praxialfoundations of multicultural music education', in D. Eliott (ed.), Praxial Music Education: Reflections and dialogues, pp. 199-204, Oxford University Press, New York.

Van Dooren, W., Verschaffel, L. & Onghena, P., 2002, 'The impact of preservice teachers' content knowledge on their evaluation of students' strategies for solving arithmetic and algebra word problems', Journal for Research into Mathematics 33(5), 319-351. [ Links ]

Vannatta-Hall, J., 2010, 'Music education in early childhood teacher education: The impact of a music methods course on pre-service teachers' perceived confidence and competence to teach music', Doctoral dissertation, University of Illinois, viewed 11 October 2017, from https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/bitstream/handle/2142/16854/1_ VannattaHall_Jennifer.pdf?sequence=4

Wits School of Education, 2009, Implementation of the National Curriculum Statement in the Foundation Phase, Wits School of Education, Johannesburg.

Wood, E., 2009, 'Developing a pedagogy of play', in A. Anning, J. Cullen & M. Fleer (eds.), Early childhood education: Society and culture, pp. 27-38, Sage, London.

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Alta van As

aletta.vanas@wits.ac.za

Received: 24 Feb. 2017

Accepted: 03 Aug. 2018

Published: 29 Nov. 2018

1 . Musical concepts are learned through singing, chanting, dance, movement, drama and the playing of percussion instruments. Improvisation, composition and a child's natural sense of play are encouraged (Estrella n.d.).

2 . The Dalcroze approach to music education teaches an understanding of music - its fundamental concepts, its expressive meanings, and its deep connections to other arts and human activities - through ground-breaking techniques incorporating rhythmic movement, aural training, and physical, vocal and instrumental improvisation (Dalcroze Society of America n.d.).

3 . The Kodaly method is a philosophy of music education that develops a complete musician through the finest musical experiences. Each concept is learnt through aural, visual, kinesthetic and cognitive activities (Orpheus Academy of Music n.d.). Kodaly believed that 'if one were to attempt to express the essence of this [Kodaly approach to] education in one word, it could only be - singing''.

4 . Teaching experience refers to work integrated learning. It is the block of time that students spend in the schools honing their practical teaching experience.

5 . A music ring is a teacher-guided activity that usually includes all the children in the group. It lasts between 15 and 30 min, depending on the age of the children.