Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Childhood Education

On-line version ISSN 2223-7682

Print version ISSN 2223-7674

SAJCE vol.8 n.1 Johannesburg 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v8i1.522

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Absent fathers' socio-economic status and perceptions of fatherhood as related to developmental challenges faced by children in South Africa

Ishola A. Salami; Chinedu I.O. Okeke

School of General and Continuing Education, University of Fort Hare, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: There has been increased attention to the problem of fathers' absenteeism and fathers' participation in the socio-educational development of children among scholars in South Africa in the last decade. Studies have been carried out on extent, causes and possible interventions for fathering in the country. The majority of these studies have adopted a qualitative research approach, which has limited their ability to determine scientifically the cause-effect relationships that exist among several factors identified as the causes and the problems generated by fathers' absenteeism, hence this study

AIM: The aim is to determine which of the socio-economic factors as well as the fathers' perception would significantly determine the challenges faced by the children

SETTING: The study was carried out in one of the universities that have Foundation Phase teacher education programmes in Eastern Cape Province

METHODS: Ex post facto research design was adopted to carry out this study. The sample of the study is 300 participants, out of which 43% are male and 57% are female participants; 78% of the teachers are black, 13% are white, 7% are mixed race and 2% are Indian

RESULTS: There is a significant composite contribution of socio-economic factors and fathers' perception on developmental challenges faced by the children (F(6, 293) = 3.74; p < 0.05) among other findings

CONCLUSION: Inculcation of fathering skills in secondary schools for boys and establishment of a government agency that will ensure equal opportunities for socio-economic status of South African fathers irrespective of their race were recommended

Introduction

The relationship and effectiveness of a couple in the process of family management and childrearing activities can be likened to that of a pair of eyes, ears, hands or legs. When one of these organs is disabled, the effectiveness of that organ is negatively and significantly affected. This must be the reason behind the growing attention among scholars to the problem of absentee fathers, most especially in those societies where fathers' absenteeism and low participation in family affairs is observed. When this happens, the children are usually at the receiving end of the negative impacts. Exposing children to a poor fathering experience not only negatively affects their holistic development but is likely to be transmitted to the next generation (Gould & Ward 2015; Makusha & Richter 2015; Ward, Makusha & Bray 2015). In order to effectively address this problem, this study, through a quantitative method, studied not only the factors that contribute to the fathers' extent of participation but also determined which of the factors have significant contributions to challenges facing the children during the formative years.

The works of Ooms, Cohen and Hutchins (1995), Flishing (2005), Peeters (2007), Richter, Chikovore and Makusha (2010), the United Nations (2011), Nyanjaya and Masango (2012), Okeke (2014), Shwalb and Shwalb (2014), Makusha and Richter (2015), Mncanca, Okeke and Fletcher (2016) and a host of others reveal that the problem of fathering cuts across developed, developing and non-developed nations. Consequently, many scholars in the areas of Psychology, Sociology, Early Childhood Education and other related areas have researched the problem and revealed some facts.

Over the past two decades more attention has been given to fathering in many countries of the world, including South Africa, but the problem as well as the effects it has on children's lives and development does not seem to be decreasing (Ratele, Shefer & Clowes 2012). This calls for scientific studies that can identify, in a more scientific way, those factors that have significant cause-effect relationships with fathering so as to know what kind of interventions should be provided in order to reduce poor fathering practices and improve child development in these societies.

Challenges faced by children experiencing father absenteeism

The literature abounds on challenges faced by children whose fathers are unable to participate in their socio-educational development (Change 2015; Chauke & Khunou 2014; Gray & Anderson 2016; Horn 2002; Lindegger 2006; Mncanca & Okeke 2016; Palkovitz 2002; Richter et al. 2010). In terms of social development and emotional stability, which is a significant determinant of cognitive functionality, Richter et al. (2010) submit that fathers' absence hinders children from receiving and giving love; the lack of a father-child relationship reinforces the pain children feel. Gray and Anderson (2016) support this by submitting that fathers' absence has direct effect on socio-emotional state and behavioural problems of children.

Physical, mental health, social competence, later IQ and other learning outcomes of children whose fathers are not involved in their socio-educational development have been reported to be poorer compared with children whose fathers are physically present and participating in the processes and programmes of their development (Amato 2000; Gray & Anderson 2016; Hofferth 2006; Ward et al. 2015). So far, scholars have shown how the holistic development (social, emotional, physical and intellectual) of children is at stake when their fathers are unable to participate in the provision of their developmental demands.

Nor are other domains of development spared when a father's participation is lacking in the life of an individual. For instance, Richter et al. (2010) reported that children whose fathers are in absentia might face poor nutrition and healthcare services; in addition, their schooling might not be encouraged or supported, which might eventually lead to school dropout. Moreover, such children will not enjoy their fathers' protection and will be denied any benefits from their fathers' position in the community. Gray and Anderson (2016) support this by associating fathers' absenteeism with children's survival in terms of protection against enemy threats. These scholars also reported that this problem is associated with infant mortality in the USA and is one of the primary risk factors for child abuse or infanticide in many other countries.

Boys growing up without involved fathers are likely to develop 'hypermasculine' behaviours such as aggression and emotional instabilities (Holborn & Eddy 2011), while girls who grow up without fathers are more likely to develop lower self-esteem, a high level of risky sexual behaviour and difficulties in forming and maintaining romantic relationships later in life (Malherbe 2015). Children in absentee father households might become victims of violence or AIDS and be susceptible to drug or alcohol abuse, risky sex and involvement in crime (Gould & Ward 2015; Makusha & Richter 2015).

The argument of this paper is not that every child whose father is unable to participate in the socio-educational development will face all these challenges but that at least some of them will; however, the extent to which the mother can play an active role in the developmental processes and programme of her children might reduce the challenges they face.

Fathers' participation in children's development in South Africa

Being a husband is not the same as being a father. The meaning of the term fathering rests heavily on the presence of a child in the family, because a married man who is yet to have a child cannot be called a father. Therefore, fathering responsibilities are oriented more towards the child than to the home and the wife. In supporting this, Chauke and Khunou (2014) submit that when a father fails to provide financial support for his children, his parenting status and powers are relinquished.

The literature has it that the state of fathers' absenteeism and their low participation in the lives of their children is a societal malice confronting South Africa as a nation in this present age (Madhavan, Townsend & Garey 2008; Makusha & Richter 2015; Mncanca & Okeke 2016; Richter 2006; Richter et al. 2010). In the words of Richter et al. (2010), South Africa has the second highest rate of fathers' absence, low rates of paternal maintenance for children and high rate of abuse and neglect of children by men. Gould and Ward (2015) claim that 50% of children in South Africa grow up in families with fathers in absentia. It was also reported that only one-third of preschool children co-reside with their fathers in South Africa (Makusha & Richter 2015).

There are two issues concerning fathering in South Africa, as reflected in the literature, that are worth noting. The first is the issue of absent fathers, while the other is the issue of fathers' participation. A father's physical absence in the home does not necessarily translate to non-participation in the socio-educational development of the children, nor does a father's physical presence in the home automatically translate to holistic development of the children (Chauke & Khunou 2014; Gould & Ward 2015; Richter 2006). This therefore means that the focus of this paper is the extent of fathers' participation in the socio-educational development of the children. The term absent fathers is used here to mean fathers who are unable to participate actively in the fathering roles expected in terms of social, emotional, economic and protective contributions and providing for their children.

In their work titled First Steps to Healing the South African Family, Holborn and Eddy (2011) point out the fact that fathers' involvement in the socio-educational development of their children has direct and indirect influences on the child. Length of time spent in school, educational attainment, self-confidence, adjustment and behavioural control abilities were claimed to be the direct influence, while indirect influences are the supports given to the mother and contributions to the major decisions taken at home. Richter (2006), Richter et al. (2010), Mercer (2015), Makusha and Richter (2015) and Adamsons (2016) reported that South African fathers, most especially black people, have the intention to take part in the socio-educational development of their children but cannot do much in terms of provision of financial and material things as a result of many factors such as cultural and economic issues. Richter (2006) observes that much of the literature on fathers' participation in South Africa based their conclusions mainly on physical availability at home and hands-on care for the children but that if human capital, financial capital, social capital and protection services are considered, most fathers do participate. Madhavan et al. (2014), supporting Richter's argument, say that fathers do make available financial supports for their children even when they are no longer married to the mothers.

As said earlier, fathers' presence or absence at home does not give the accurate measure of their level of participation in the socio-educational development of their children. The extent of challenges experienced by the children will also vary based on the extent of their fathers' participation and the factors militating against fathers' participation. There is the need, therefore, to scientifically trace those factors that make significant contributions to the extent of fathers' participation and hence the possible challenges facing their children during the formative years. In order to address this problem, this study employed a quantitative research approach to measure the socio-economic factors, fathers' perceptions of fatherhood and the challenges facing children whose fathers could not participate in their socio-educational development. The significant relationships that exist between each of the identified factors and the challenges were determined.

Theoretical framework

The educational theory that formed the basis for this study is the ecological systems theory, propounded by Urie Bronfenbrenner in 1979. The theory states that as a child develops, the interaction within the environments becomes more complex and that this complexity can arise as the child's physical and cognitive structures grow and mature (Bronfenbrenner 1986). In other words, the inherent qualities of a child and his environment interact to influence how such child grows and develops. The theory explains how child development is influenced by a number of environmental and interpersonal factors, which are clustered in several environmental systems. In the words of Excell, Linington and Schaik (2015), environment is a system of circles nested inside each other with the child at the centre and the circles or systems interact with and influence each other, as well as influencing the development of the child. The systems presented by the theory are the microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem and chronosystem, but the focus of this study is explained by one of the factors in the microsystem. The microsystem is the one closest to the child and it includes the home - father, mother, siblings and other relatives, adults, peers and neighbours (Penn 2005). Bronfenbrenner submits that interactions within the microsystem involve personal relationships with family members and other members of the system. He further explains that how these members or individuals interact with the child will affect how the child develops. More nurturing and more supportive interactions and relationships will enhance the child's development. Literature also has it that fathers' behaviours and roles, though socioculturally based, have an intense influence on the total development of the children (Gray & Anderson 2016). This corroborates the submissions of Richter (2006) that fathers were the providers and protectors of the typical African family before the advent of Western imperialists. Richter also argues that in a typical African family, the role of the mother usually tends towards care and love while that of the father tends to provision, protection and guidance, career support and discipline.

This study is of the position that fathers' socio-economic status coupled with their perceptions of a father's role are capable of affecting the extent to which they meet their responsibilities of provision, protection, guidance and career support. Moreover, the extent to which these responsibilities are met or otherwise, according to the ecological system theory, will influence the holistic development of the child.

Objectives of the study

The major objective of this study was to determine which of the socio-economic factors as well as the perceptions of the fathers about their participation in the socio-educational development of their children would significantly determine the challenges faced by the children. Specifically, the study examined the following:

-

the relationship that exists between each of the socio-economic factors and fathers' perceptions and the challenges faced by their children during their early development

-

the composite contribution of socio-economic factors and fathers' perceptions to the challenges faced by children during their early development

-

the relative contributions of socio-economic factors and fathers' perceptions to the challenges faced by children during their early development.

Research questions

-

What type of relationship exists between each of the independent variables (socio-economic factors and fathers' perceptions) and the dependent variable (challenges faced by children during their early years)?

-

Is there a significant composite contribution of socio-economic factors and fathers' perceptions to the challenges faced by the children during their early development?

-

Is there a significant relative contribution of socio-economic factors and fathers' perceptions to the challenges faced by children during their early development?

Methodology

The study adopted an ex post facto type of causal comparative research design. This design is capable of collecting already-existing data on independent variables (one of which must be a categorical variable) and a dependent variable from sampled participants, analyse it and find out if there are any cause-effect relationships between the independent and dependent variables (Ary, Jacobs & Sorensen 2010; Isangedighi et al. 2004). Ary et al. claim that ex post facto research design remains the last option when variables of great interest that are not amenable to experimental research are to be studied for cause-effect relationships. For instance, random assignment of children into attribute variables such as 'fathers' absenteeism', 'fathering skills' and 'challenges faced' is not possible; hence, the cause-effect relationship of such variables cannot be determined through experimental study.

The independent variables of this study are socio-economic factors (financial factors, father's absenteeism, fathering skills, relationship with the mother and father's race) and fathers' perception of fatherhood. The one categorical independent variable is the fathers' race, while the dependent variable is the challenges faced by the children. The target population of the study is the entire population of educated fathers and young adults in Eastern Cape Province. The reason for this population was to ensure that participants of this study were not only well-educated individuals but had knowledge about children's education and development, as well as having some level of experience with fathering in South Africa. Faculty of Education students at the University of Fort Hare were used as a case study. A sample of 300 students of the School of General and Continuing Education (SGCE), at the East London campus of the university, were randomly selected. The sample of the study consists of the following distributions: Marital status of the students showed that 20% of the students were married, 69% were single and 11% were divorced. The sample had a gender distribution of 43% male and 57% female students. The racial makeup of the students was 78% black students, 13% white students, 7% mixed-race students and 2% Indian students. The socio-economic factors, Fathers' Perception and Challenges Faced by Children Questionnaire (SeFP_CFCQ: α = 0.92) was used to collect data. SeFP_CFCQ has four sections: Section A measures demographic data, Section B measures socio-economic factors (19 items), Section C measures fathers' perceptions of fatherhood (25 items) and Section D measures the challenges faced by children during their early development (16 items). The response options for Sections B to D are on a five-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (SD) to strongly agree (SA) and were scored from 1 to 5, in that order. Data collected was analysed using both descriptive statistics and multiple regression, and significance was measured at the 0.05 level.

Results

Research Question 1: What type of relationship exists between each of the independent variables (socio-economic factors and fathers' perceptions) and the dependent variable (challenges faced by children during their early years)?

The correlation coefficients in the second column, starting from the third row (Table 1), show that the following independent variables had a significant relationship with the challenges faced by children: financial factors (r = 0.13; p < 0.05); fathering skills (r = 0.21; p < 0.05); relationship with the mother (r = 0.18; p < 0.05) and race (r = -0.15; p < 0.05). However, absenteeism (r = 0.10; p > 0.05) and fathers' perceptions (r = 0.04; p > 0.05) had no significant relationship with the challenges faced by children whose fathers were in absentia.

Research Question 2: Is there a significant composite contribution of socio-economic factors and fathers' perceptions to the challenges faced by the children during their early development?

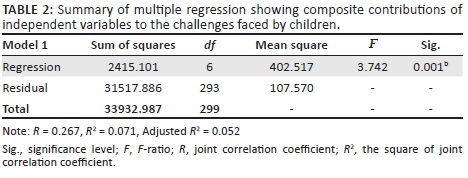

There was a joint relationship (Table 2) between the independent variables (socio-economic factors and fathers' perceptions) and the challenges faced by the children (R = 0.27). This led to the fact that the independent variables, when taken together, accounted for 5.2% of the total variance in the challenges faced by the children (adjusted R2 = 0.052). This composite contribution was shown to be significant (F(6, 293) = 3.74; p < 0.05). This implies that there is a significant composite contribution of socio-economic factors and fathers' perception to challenges faced by the children.

Research Question 3: Is there a significant relative contribution of socio-economic factors and fathers' perceptions to the challenges faced by children during their early development?

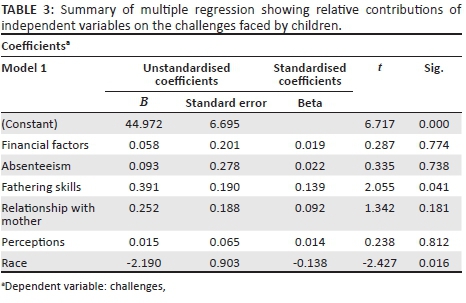

The columns with the beta, t-test and significance values in Table 3 show that out of the six independent variables considered in this study, it is only fathering skills (β = 0.14; t = 2.06; p < 0.05) and race (β = -0.14; t = -2.43; p < 0.05) that had a significant relative contribution to the challenges faced by the children. Others, that is, financial factors (β = 0.02; t = 0.29; p > 0.05); absenteeism (β = 0.02; t = 0.33; p > 0.05), relationship with the mother (β = 0.09; t = 1.34; p > 0.05) and fathers' perceptions (β = 0.01; t = 0.24; p > 0.05) had no significant relative contribution to the challenges faced by the children. Therefore, it can be inferred that it is only fathering skills and race of the father that make significant relative contributions to the challenges faced by children whose fathers are unable to participate in their socio-educational development.

Summary of findings

After the analysis and interpretation of the outcomes, the findings of this study are summarised as follows:

-

Socio-economic factors - financial factors, fathering skills, relationship with the mother and race of the fathers - have a significant relationship with the challenges faced by the children whose fathers are unable to participate in their socio-educational development, while absenteeism and fathers' perception have no significant relationship with the challenges faced by children.

-

There is a significant composite contribution of socio-economic factors and fathers' perceptions of fatherhood to the challenges faced by children whose fathers are unable to participate in their socio-educational development.

-

It is only fathering skills and the race of the father that make significant relative contributions to the challenges faced by the children.

Discussion of findings

The first finding of this study is that some socio-economic factors, that is, financial factors, fathering skills, relationship with the mother and race of the father, are the ones that have significant relationships with the challenges faced by children whose fathers are unable to participate in their socio-educational development. This might be because the financial capacity of fathers is capable of determining how much they can afford in their expected roles (Chauke & Khunou 2014; Gould & Ward 2015; Gray & Anderson 2016; Richter et al. 2010). Moreover, Richter et al. (2010) and Madhavan et al. (2014) also submitted that the search for a good job in order to have enough money to take care of their family is one of the major reasons black fathers do not reside with their children.

Fathering skills, which most men acquire from their fathers, are another important factors that dictate how much care, love, protection and provision South African fathers give to their children (Holborn & Eddy 2011; Mercer 2015). This happens because most of the fathers did not experience positive fathering themselves (Madhavan et al. 2008; Mncanca & Okeke 2016).

A study carried out by Mufutau and Okeke (2016) noted that the relationship between the biological father and the mother of the child goes a long way to affect how much the father will likely participate in the socio-educational development of the child(ren). Race in South Africa also plays a significant role in how much fathers participate in their children's development. Holborn and Eddy (2011), Ratele et al. (2012) and Mncanca et al. (2016) found that fathers' absenteeism and fathers' low involvement in their children's socio-educational development is high among black people and lowest among white fathers. Therefore, this finding that financial factors, fathering skills, relationship with the mother and race of the fathers have significant relationships with the challenges faced by the children should not be overlooked.

The second finding of this study is that there exist significant joint contributions of socio-economic factors and fathers' perceptions of fatherhood to the challenges faced by children whose fathers are unable to participate in their socio-educational development. These socio-economic factors and the fathers' perceptions were estimated to account for 5% of the total variance in challenges faced by the children. The contribution seems small, but it is statistically significant and hence worth taking cognisance of. Many studies that have tried to identify the causes of absent fathers or fathers' low participation in their children's development have asserted that socio-economic factors play major roles (Adamsons 2016; Chauke & Khunou 2014; Gould & Ward 2015; Holborn & Eddy 2011; Makusha & Richter 2015; Mufutau & Okeke 2016; Richter 2006). Therefore, socio-economic factors should be reckoned with as playing a significant role in both fathers' absenteeism and fathers' low participation in their children's socio-educational development.

Lastly, this study found that only fathering skills and race of the fathers have significant relative contributions to the challenges faced by their children. This should not be seen as a contradiction to the earlier claim that socio-economic factors have a significant contribution to the challenges faced by children. This last finding is only specifically identifying which of the socio-economic fathers have a greater and more significant contribution. Fathering skills, which can be referred to as the technical know-how of being a father, may play a major role in the challenges of children. It is one thing to know what is good for children; the ability to do what is in children's best interest such that the children will recognise it as being good is another. It is one thing to have the love of a child at heart and yet another to be able to show love and care for such a child. This might be the reason why Mncanca et al. (2016) submit that fathering is a complex phenomenon that cannot be measured by physical availability at home, hands-on care and provision of financial support. As reported by Holborn and Eddy (2011), Ratele et al. (2012) and Mncanca et al. (2016), black fathers in South Africa recorded the highest rates of absenteeism and lowest rates of participation and white fathers just the opposite. Therefore, this means that white children face fewer developmental challenges compared to mixed-race, Indian and black children. This shows that race plays a significant role in determining the challenges faced by children during their early years.

Conclusion

In the quest to identify the major causes of fathers' inability to participate or low participation in the socio-educational development of their children, this study adopted an ex post facto research design, collected quantitative data and utilised inferential statistics to analyse the data. The study found out that fathering skills and race of the fathers are the two socio-economic factors that significantly influenced fathers' participation in their children's socio-educational development. Other factors such as financial factors and relationship with the mother have a significant relationship with the fathers' participation while all the factors in conjunction with fathers' perceptions of fatherhood have composite contribution to the fathers' participation.

Effective solutions to the problem of fathers' low participation in the socio-educational development of their children must be tailored towards financial empowerment for fathers, most especially black fathers. Again, there is need to put in place an effective mechanism that will ensure economic egalitarianism among the four races that make up South African society.

Recommendations

-

The South African government should endeavour to set up an agency in the country that will ensure equal opportunities for all South African men to access functional higher education and employment irrespective of their race. This is to ensure better socio-economic status for fathers. If possible, special consideration should be given to black men because the apartheid era put them in a disadvantaged state.

-

Fathering skills should be embedded in the curriculum of secondary education, most especially for boys, so as to equip all of them, irrespective of the condition of their fathers, with the necessary skills to be a good father. This should be done in the form of extracurricular activities, after-school activities or men's club. If these are attended to and implemented religiously, poor fathering practices that are currently militating against societal development in one way or another will become a thing of the past in the near future.

Acknowledgements

The study reported in this article was sponsored with a SEED grant from the Govan Mbeki Research and Development Centre, University of Fort Hare, Eastern Cape, South Africa

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships which may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

C.I.O.O was the research leader and also collected the data while I.A.S. reviewed the literature, analysed the data and wrote out the report.

References

Adamsons, K., 2016, 'Commonalities and diversities of fathering, overall commentary on fathering', in J.L. Roopnarine (ed.), Father - Paternity. Encyclopaedia on early childhood development, pp. 39-42, Syracuse University Press, NY.

Amato, P.R., 2000, 'The consequences of divorce for adults and children', Journal of Marriage and the Family 62, 1269-1287. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.01269.x [ Links ]

Ary, D., Jacobs, L.C. & Sorensen, C., 2010, Introduction to research in education, Wadsworth Cengage Learning, CA, United States.

Bronfenbrenner, U., 1986, 'Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives', Developmental Psychology 22(6), 723-742. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.22.6.723 [ Links ]

Change, B., 2015, 'Reaching fathers', International Journal of Childbirth Education 30(1), 9-15. [ Links ]

Chauke, P. & Khunou, G., 2014, 'Shaming fathers into providers: Child support and fatherhood in the South African media', The Open Family Studies Journal 6(12), 18-23. [ Links ]

Excell, L., Linington, V. & Schaik, N., 2015, 'Perspectives on early childhood education', in L. Excell & V. Linington (eds.), Teaching grade R., pp. 15-36, Juta and Company Ltd, Cape Town, South Africa.

Flishing, B., 2005, 'A few remarks on men in child care and gender aspects in Sweden', A paper contribution to the Conference on Men in Child Care held in London on September 19, 2005.

Gould, C. & Ward, C.L., 2015, Positive parenting in South Africa: Why supporting families is key to development and violence prevention, Institute for Security Studies, Policy Brief 77, Pretoria, South Africa.

Gray, P.B. & Anderson, K.G., 2016, 'The impact of fathers on Children', in J.L. Roopnarine (ed.), Father - Paternity. Encyclopaedia on early childhood development, pp. 6-12, Syracuse, NY.

Hofferth, S., 2006, 'Residential father family type and child well-being: Investment versus selection', Demography 43, 53-77. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2006.0006 [ Links ]

Holborn, L. & Eddy, G., 2011, First steps to healing the South African family. A research paper by the South African Institute of Race Relations, South African Institute of Race Relation Press, Johannesburg.

Horn, W.F., 2002, Father facts, National Fatherhood Initiative, Washington, DC.

Isangedighi, A.J., Joshua, M.T., Asim, A.E. & Ekuri, E.E., 2004, Fundamentals of research and statistics in education and social sciences, University of Calabar Press, Calabar, Nigeria.

Lindegger, G., 2006, 'The father in the mind', in L. Richter & R. Morrell (eds.), Baba: Men and fatherhood in South Africa, pp. 121-131, HSRC Press, Cape Town, South Africa.

Madhavan, S., Richter, L., Norris, S. & Hosegood, V., 2014, 'Fathers' financial support of children in a low income community in South Africa', Journal of Family and Economic Issues 35, 452-463. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-013-9385-9 [ Links ]

Madhavan, S., Townsend, N. & Garey, A.I., 2008, 'Absent breadwinners: Father-child connections and paternal support in rural South Africa', Journal of Southern African Studies 34, 647-663. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070802259902 [ Links ]

Makusha, T. & Richter, L., 2015, 'Non-resident Black fathers in South Africa', in J.L. Roopnarine (ed.), Father - Paternity. Encyclopedia on early childhood development, pp. 30-33, Syracuse University Press, NY.

Malherbe, N., 2015, 'Interrogating the "crisis of fatherhood": Discursive constructions of fathers amongst peri-urban Xhosa-speaking adolescents', A Master's Dissertation, University of Cape Town, Cape Town.

Mercer, G.D., 2015, 'Do father care? Measuring mothers' and fathers' perceptions of fahters' involvement in caring for young children in South Africa', A Doctoral Thesis, The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada, 295 p.

Mncanca, M. & Okeke, C.I.O., 2016, 'Positive fatherhood: A key synergy for functional early childhood education in South Africa', Journal of Sociology and Anthropology 7(4), 221-232. https://doi.org/10.1080/09766634.2016.11885720 [ Links ]

Mncanca, M., Okeke, C.I.O. & Fletcher, R., 2016, 'Black fathers' participation in early childhood development in South Africa: What do we know?', Journal of Social Science 46(3), 202-213. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718923.2016.11893528 [ Links ]

Mufutau, M.A. & Okeke, C.I.O., 2016, 'Factors affecting rural men's participation in children's preschool in one rural education district in Eastern Cape Province', Studies on Tribes and Tribals 14(1), 18-28. https://doi.org/10.1080/0972639X.2016.11886728 [ Links ]

Nyanjaya, A.K. & Masango, M.J., 2012, 'The plight of absent fathers caused by migrant work: Its traumatic impart on adolescent male children in Zimbabwe', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 68(1), 167-177. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v68i1.1004 [ Links ]

Okeke, C.I., 2014, 'Effective home-school partnership: Some strategies to help strengthen parental involvement', South African Journal of Education 34(3), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.15700/201409161044 [ Links ]

Ooms, T., Cohen, E. & Hutchins, J., 1995, 'Disconnected dads: Strategies for promoting responsible fathers', Background Brief Report of the Policy Institution for Family Impact Seminar held on June 23, 1995 at Washington, DC.

Palkovitz, R., 2002, Involved fathering and men's adult development: Provisional balances, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hills Dale, NJ.

Peeters, J., 2007, 'Including men in early childhood education: Insight from the European experience', New Zealand in Early Childhood Education 10, viewed 16 January 2017, from www.vbjk.be/ecce_ama.htm [ Links ]

Penn, H., 2005, Understanding early childhood education issues and controversies, Bell & Bain Press, Glasgow.

Ratele, K., Shefer, T. & Clowes, L., 2012, 'Talking South African fathers: A critical examination of men's constructions and experiences of fatherhood and fatherlessness', South African Journal of Psychology 42(2), 553-563. https://doi.org/10.1177/008124631204200409 [ Links ]

Richter, L., 2006, 'The importance of fathering for children', in L. Richter & R. Morrell (eds.), Baba: Men and fatherhood in South Africa, pp. 53-61, HSRC Press, Cape Town, South Africa.

Richter, L., Chikovore, J. & Makusha, T., 2010, 'The status of father and fathering in South Africa', Childhood Education 86(6), 360-365. https://doi.org/10.1080/00094056.2010.10523170 [ Links ]

Shwalb, D.W. & Shwalb, B.J., 2014, 'Fatherhood in Brazil, Bangladesh, Russia, Japan and Australia', Online Reading in Psychology and Culture 6(3), viewed 16 January 2017, from https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1125. [ Links ]

United Nation, 2011, Men in families and family policy in a changing world, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, viewed 16 January 2017, from http://www.um.org/esa/socdev/family/docs/men-in-families.pdf

Ward, C., Makusha, T. & Bray, R., 2015, Parenting, poverty and young people in South Africa: What are the connections? South African Child Gauge, Cape Town, South Africa.

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Ishola Salami

snappy600@gmail.com

Received: 02 Feb. 2017

Accepted: 04 Aug. 2018

Published: 13 Nov. 2018