Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Childhood Education

On-line version ISSN 2223-7682

Print version ISSN 2223-7674

SAJCE vol.8 n.1 Johannesburg 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v8i1.557

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

'Clutch-the-ear' and get enrolled: The antagonistic intrusion of indigenous knowledge systems to the detriment of contemporary educational developments

Felistas R. ZimanoI; Keresencia MatsaureII; Alouis ChilunjikaIII

IDepartment of Sociology and Social Anthropology, Great Zimbabwe University, Zimbabwe

IIMufakose Mhuriimwe Secondary School, Zimbabwe

IIIDepartment of Politics and Public Management, Midlands State University, Zimbabwe

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: The use of non-conventional methods of measurement is a long-established practice in most societies

AIM: To investigate the effectiveness of non-conventional methods of measurement in the placement of children in schools in general and the 'clutch-the-ear' and get enrolled age measurement practice in particular. To expose the shortfalls of a classroom setup in which age-for-grade enrolment is distorted

SETTING: Zimbabwe

METHODS: Literature review and researchers experiences

RESULTS: The use of non-conventional methods has both pros and cons. The practice can be hailed for showing the indigenous knowledge systems as giving, to an extent, transparent and accurate maturity prediction ways that require preservation. However, it works perfectly for people of average height while prejudicing the outliers. The immediate conspicuous consequence is the late enrolment of the affected. In the case of the 'clutch-the-ear' and get enrolled measure, findings are discussed below

CONCLUSION: The use of non-conventional methods of age measurement unobtrusively upsets education quality through facilitating stereotyping, discrimination and age-heterogeneous classes. Researchers propose a 'backward-integration-enrolment' strategy; getting into communities to enrol not to wait for the community to bring children to school

Introduction

Africa is rich in non-conventional ways of measuring objects or events and predicting events or action. Through indigenous knowledge systems (IKSs), predictions have been made for almost every occurrence in human life. This is a situation when IKSs are used in the context of defining a social phenomenon. IKSs allow predictions to be made for literary all occurrences relevant to people's life (Soropa et al. 2015). There are predictions done by ordinary people through reading signs and symbols, while other predictions are done by experts: spirit mediums or 'bone-throwers'. In many communities, IKS becomes the basis for most 'local-level decision-making' (Soropa et al. 2015). This article draws attention to the implications of some IKS practices for educational developments through interrogating a traditional maturity prediction method. For the purpose of this article, the researchers will name the method the 'clutch-the-ear'maturity prediction method. This term, as will be explained in forthcoming sections, is coined from the way the maturity prediction test is carried out in which children are asked to clutch one of their ears. This practice is extensively, though informally, used to ascertain children's maturity for enrolment into the formal education system. The researchers, all Zimbabweans, have experienced this practice and traced it to pre-colonial times through oral tradition. The education-related concepts to be tackled in the understanding of this IKS practice are randomly drawn from literature. Through concepts such as age-heterogeneity, juvenile delinquency, age-for-grade and enrolment, the developments in education alongside IKS are investigated. The sample of concepts used herein involves only concepts relating to enrolment of children into schools and those pertaining to society's beliefs and practices.

The 'clutch-the-ear' concept entails a practical procedure in which children use their hand to clutch the ear at the opposite side to the hand. This means taking the right hand, over the head, to hold the left ear or vice versa. Since time immemorial, the successful completion of this task signified a child's maturity for more demanding task like herding goats, monitoring animal traps and so forth. With the beginning of colonisation, locals continued to use this measure to determine children's readiness for enrolment into the formal education system. Failure to clutch the opposite ear means one is not yet due for formal education or more demanding responsibilities. This method, as the article will discuss, is correct and relevant to a great extent. However, the method's inadequacy comes in its inability to deal with outliers and the subsequent prejudices in their accessing education. Those of below or above average height are bound to be victims. Those with below average height will require more years than their age-mates to succeed in this task. The opposite scenario obtains for those with above average height. While the former will enrol for formal education later than their age-mates, the latter will get enrolled earlier. In both cases, children get disadvantaged. The prejudice is worse in those children living with disabilities. These will get to school long after their age-mates, if at all they eventually get the opportunity. Through listening and evaluating such marginalised stories, a complete understanding of IKS can prevail (Ramose 2016). This 'clutch-the-ear' maturity prediction method is widely used to date, though informally, in Zimbabwe's rural and urban areas.

This article has two focal objectives. Through isolating the maturity prediction practice and analysing it, the article seeks to placate the ardent advocacy for unchallenged adoption of IKS that is going on in various scholarly spheres. On the one hand, there are IKS methods proven relevant by research. An example is the climate indicators from IKS in which knowledge of 'wild fruits, trees, worms and birds' flowering, quantities, breeding and migratory patterns has proved to be consistent with modern climate predicting methods (Soropa et al. 2015). On the contrary, there are a number of intelligent solutions of IKS that fall short to contemporary demands. For example, there are biases and discrimination prevalent in African societies (Dickson & Mbosowo 2014). Yet, there is a general fortification of African epistemologies as superior and pure (Baloyi & Ramose 2016).The researchers' opinion is that the bona fide significance of IKS can be brought out by objective interrogation through looking at practices' implications to the good of humanity. This will permit the adoption and preservation of worthy IKS for contemporary and future use. The biased and indiscriminate defending of IKS defeats and annihilates the quest to extract real value out of them and must be restrained. A greater acceptance and use will only come through increased exposure of facts such that corrections are made where they are due. By so doing, knowledge users and future generations will give more value to the IKS scholarly work, realising its mission as not mere veneration of the marginalised methods but objective questioning and preservation of valuable intelligence. Besides, all ways of knowing must aim to 'understand experience so that it can be used to ameliorate, strengthen and protect especially human life on earth' (Ramose 2016:60).

Secondly, the article seeks to contribute to the debate on challenges in the developing countries' education system by interrogating a maturity prediction method widely used, though informally, in Zimbabwe. The article focuses on hindrances to enrolment as they are inimical to the realisation of education for all targets. Some people are deprived access to education because of a lack of knowledge perpetuated by some practices and beliefs. This is worrisome because education is a fundamental condition through which economic and social developments occur, with primary education as its foundation (World Bank 2003). In a quest to ensure that education is made accessible to all, the United Nations (UN) seeks to 'ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all' (United Nations 2016:5). This is stated as the UN's fourth Sustainable Development Goal. By looking at the 'clutch-the-ear' concept, societal practices affecting the timely enrolment of children into formal education are brought to the fore. The article consequently educates people against following IKS indiscriminately, as there are some practices that perpetuate stereotypes and violation of children's rights through negative social construction. Such negative social norms also impact negatively on the utilisation of education services. For policy-makers, the article recommends a method termed herein, the 'backward-integration-enrolment'. Backward integration is widely understood in business and economics clique. In business sense, backward integration is a scenario in which a company moves to take control of its inputs supply through, for example buying a company that previously supplied it with raw materials (Olanrewaju 2016). By so doing, the company is guaranteed of a stable input supply. By the same principle, through adopting 'backward-integration-enrolment', the school goes into the community to get and possibly 'rescue' children rather than wait for parents to bring children to school for enrolment.

The 'clutch-the-ear' maturity prediction method: Some detail

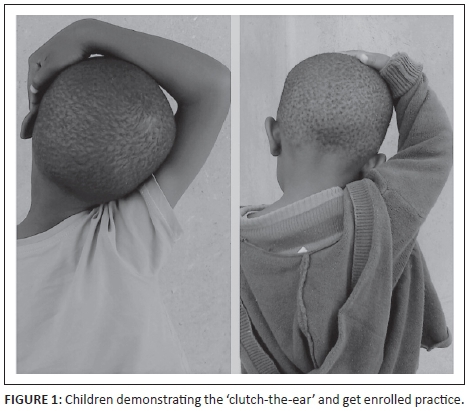

The 'clutch-the-ear' practice is in all probability not documented. We have searched in several places harbouring such type of knowledge to no avail. However, this is a common practice in Zimbabwe. Basically, it is used informally to determine one's maturity or readiness for formal education and more demanding tasks. This is a long-standing practice. The practice entails a practical test in which children who can successfully hold the ear to the opposite side of their hands will be deemed mature. The hand must go over the head to the ear as illustrated below. As shown in Figure 1, the child to the left side is ready to enrol for formal education. The one to the right is not yet mature to get enrolled into formal education as the hand has not gone far enough to clutch the ear at the opposite side. Oral tradition has it that this practise was used since time immemorial to determine children's readiness for various roles in the community. When the formal schooling system was introduced with the advent of colonisation, indigenous people continued to use the method as their maturity predictor.

Theoretical framework: Social construction of knowledge

This article utilises the social construction theory in setting out the explanation on IKS' impact on the understanding of maturity, educational development and prejudices. Generally, social construction pertains to the interest in a phenomenon that depends on a people's culture and the decisions they make (Mallon 2007). This is coming out of the understanding that 'knowledge or reality or both are contingent upon social relations and as made out of continuing human practises' (Honderich 2005:9). This social construction of knowledge deals with the way reality is constructed as well as relationships that exist between human thought and the social life realm in which it emerges (Berger & Luckmann 1966). Social constructions apply to those theories that put emphasis on the socially created or nurtured social life (Scott & Marshall 2009).

IKSs are part of people's culture. The understanding of society in the context of its culture is imperative in appreciating social construction of knowledge. It is from everyday interactions that everyday knowledge about reality is derived (Berger & Luckmann 1966). 'The concept of culture is important in the understanding of disability as cultural norms and values influence conceptions of disability' (Reid-Cunningham 2009:99). This is because it is the society that determines what is right or wrong and what is possible or impossible. 'Disability exists when people experience discrimination on the basis of perceived functional limitations' (Kasnitz & Shuttleworth 2001:2). Once that happens, people face physical or psychological restrains to their abilities.

As a consequence, this theoretical framework facilitates the understanding of IKS in general and 'clutch-the-ear' practice in particular as used to construct 'mature' children for enrolment into school. In that way, it becomes possible to comprehend the extent to which society has invented, created knowledge and made up various phenomena (Mallon 2007). This exposes prejudices, discrimination, stereotypes, stigma and faults that come along with some IKS practices. Our hope is that 'by revealing the contingency of a thing on our culture or decisions, we might alter that thing through future social choices' (Mallon 2007: 94).

The obtaining education context

There have been efforts to ensure equality in the access of education. 'Equality of educational opportunity is nearly universally regarded as a preeminent moral and social principle of society and its educational system' (Jia & Ericson 2017:97). Much has been done to ensure equal access of education through legal and material provisions. At law, 'the right to non-discrimination in the enjoyment of education rights is also protected under international law' (Heymann, Raub & Cassola 2014:131). UDHR Article 2 and ICESCR Article 2 guarantee the right to education regardless of one's 'race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status'.

Developing countries have done much to aid education via supply-side policies (Masino & Niño-Zarazúa 2016). On the contrary, there are calls to improve the composition of classrooms in terms of number and type of pupils in each class to ensure quality schooling (Jones 2016). This increased focus on education, especially primary education, came following the World Declaration on 'Education for all' (Masino & Niño-Zarazúa 2016).

In line with advancing the quality of schooling, three main drivers of change have been identified for developing countries (Masino & Niño-Zarazúa 2016). These are:

-

interventions aiming to enhance the supply-side capabilities of education institutions;

-

interventions targeting supply-side and demand-side changes in preferences and behaviours that affect the utilisation of education services;

-

bottom-up and top-down participation and management interventions.

This article ties the IKS' intelligence discussion to the interventions listed in the second category, interventions targeting supply- and demand-side changes. This covers the preferences and behaviours affecting the utilisation of education services. The associated actions for such interventions include strategies facilitating enrolment and attendance. The idea to look into the non-conventional 'clutch-the-ear' maturity prediction method in this context permits an objective interrogation of this method in particular, the IKS in general and the impact of social construction of knowledge on educational development. It also reveals the challenges impeding the optimum utilisation of educational interventions put in place to ensure the opportune enrolment of children into the formal education system.

The implications of the concept are discussed alongside age-to-grade placement in school. This is because there is evidence that despite progress made in making education available, absolute deprivation in education remains extraordinarily high throughout much of sub-Saharan Africa (UNESCO 2010). There are also concerns that despite improvements recorded in enrolments, the challenge of providing quality education still remains (The Africa-America Institute 2015). The age-for-grade placement is part of measures to ensure provision of quality education.

The African indigenous ways of knowing and imparting knowledge

African indigenous ways of education refer to a system that saw mature members of society preparing children for responsibilities and opportunities occurring in their environment or societies (Ocitti 1973). This involved, to a great extent, the knowledge of signs and their implications on their life routines. The African indigenous ways of knowing are different from those found in the Western world (Nobles, Baloyi & Sodi2016:39). In the African society, knowledge is transmitted from one generation to another through oral performances, games, social events and cultural practices (Kahyana 2016).

When it comes to ways of knowing especially predicting, IKS is rich with signs giving hindsight and foresight through such systems of divination. Divination comes in three major forms: possession, wisdom and intuition (Zuesse 1975). The outputs from divination informed the society and also became part of its education system. These, put together with societal practices, formed the basis of African curriculum and epistemologies. In short, Africans have their unique ways of knowing (Airoboman & Asekhauno 2012). African ways of knowing and education also extend areas that do not require one to be possessed by a spirit. These come as intelligence passed from generation to generation through practice and oral tradition.

'Clutch-the-ear' practice, modern education enrolment practices and social constructions

In modern day education systems, entry is age based. By and large, the formal education begins at the age of 6 (UNICEF 2012, 2016). However, it must be appreciated that albeit this age stipulation, schools do not go into the community to get children. The responsibility is on parents to bring their children to schools for enrolment when they have reached school-going age. It is in this context that the 'clutch-the-ear' age predictor is interrogated. In the event that parents rely solely on this practice, some children are bound to get affected as they will be deemed younger for school using a non-objective measure. The researchers herein are taking cognisance of the fact that there are several places where adult literacy is still very low such that parents are not conversant of the modern age-for-grade conventional practices. According to UNESCO (2010), 38% (translating into 153 million) of adult population in sub-Saharan Africa lacks basic literacy and numeracy skills essential for daily life. These researchers assume that in communities with high illiteracy levels, the use of unconventional measures becomes rife. Children may only get to be released into the formal education system when deemed mature by community standards. There is also evidence that households in rural or remote communities tend to have less access to primary education (UNESCO 2008).

Sending children to school timely is crucial for several reasons. In terms of educational development, the expansion of human capabilities and freedoms hinge on the accessibility of education (Masino & Niño-Zarazúa 2016; UNESCO 2007). 'Formal education is the primary pathway to social mobility in both developed and aspiring societies'. Factors that interfere with ones' steady progression through formal education also interfere with one's social mobility (Jia & Ericson 2017:97). These can be political, economic, sociological, technological, environmental or legal factors. Factors interfering with formal education can occur at any level of the education ladder. The negative effects of these interferences affect one's progression. According to Sunny et al. (2017:68), 'timely progression through school is an important measure for school performance, completion and the onset of other life transitions for adolescents'. As such, anything that affects one's movement up the education stages at any point directly affects one's later stages of life.

In the context of social construction of knowledge on maturity, the modern education enrolment requisites and the IKS intelligence seem not to correspond. When children are in society, they are subjected to various societal measures, and it is inevitable that socially constructed impairments can occur. The risk is, through relying on socially constructed knowledge on maturity, social arrangements and expectations can contribute to impairment and disability even where there is no such (Wendell 1996). In the absence of some societal regulations, some practices can continue to be used. Sometimes, practices done, with sincere intentions or because of ignorance, negatively affect the utilisation of formal education systems.

Utility and challenges of the 'clutch-the-ear' method

In the opinion of these researchers, to a great extent, the method provides accurate ways of predicting maturity and boosting confidence in those approved as mature. The approval comes as a social reinforcement. The system is passed from generation to generation through practice. It is a transparent way of doing things and is free from manipulation. To date, most parents still subject their children to this maturity predictor test although bound by and conforming to the stipulated conventional enrolment ages.

However, predicting one's maturity for enrolment into formal education through the unconventional 'clutch-the-ear' can have negative effects on one's progression. There is evidence of continued use of non-conventional methods for determining children's maturity. According to Nonoyama-Tarumi et al. (2010), late school entries take place on account of parental perception on the child's readiness for school (physical, social and cognitive), financial need and distance to school. The mentioning of parents' perception here points to the continued use of such non-conventional methods like this 'clutch-the-ear' practice under discussion herein. The consequences directly affect enrolment as children end up getting enrolled late. Most of the associated challenges relate to education quality, school completion chances and psychological effects.

Through the use of this method, children with a below average height will get into school later than their age-mates. According to Wils (2004), children who are older at entry have higher repetitions, dropouts and lower school completion rates. A southern African study established that those over age for their grade by 2 or more years were more likely to drop out at later stages (Branson et al. 2014). In times of economic hardships, older children's chances of dropping out are also exacerbated as they are co-opted into fending for the family (Pufall et al. 2016). For example, the then Ministry of Education, Sports, Art and Culture reported that in 2009 the number of boys dropping out of school was more than girls (Government of Zimbabwe/United Nations Country Team 2010). This was at the peak of Zimbabwe's economic crisis, and this dropout can be attributed to the older boys being withdrawn from school to help fend for the family.

Late entry into school also leads to reduced school completion chances for girls. In some communities, the pressure to get married mounts for older girls (Bhagavatheeswaran et al. 2016). This reduces the chances of completing school for those enrolled late. The irony is that at this point, the community will start to evaluate girls' readiness for marriage using biological factors. This does not take into cognisance the years lost before starting school. As such, those who enrolled late have a higher chance of being married off before completing formal schooling widening the gender gap in education. According to Pufall et al. (2016), female adolescents are more inclined to stay in school if they are in the correct 'grade-for-age'.

The effects of marriage before completing school are widely documented (Delprato, Akyeampang & Dunne 2017; Ganira et al. 2015; Özcebe & Biçer 2013; Psaki 2014). A society that does not educate women is its own enemy. 'Advantages conferred to women through education are subsequently transmitted to their offspring' (Kamanda, Madise & Schnepf 2016). Mothers play a very crucial role in the child's health and socialisation from neo-natal stages up until grown up. 'In terms of non-monetary influences, education has been found to affect personal health and nutrition practices, childrearing and participation in voluntary activities' (Heyneman & Lee 2016:9). So, the levels of education for women in a given community determine its prosperity.

One's chances in life are automatically affected by one's level of education. The conventional economic system is based predominantly on merit. A merit-based system means one has to produce evidence of successfully completing formal education to productively participate in the formal economy. As such, the principle of merit legitimates subsequent social and economic inequalities that those who do not progress with education to completion levels, will suffer for the rest of their lives (Jia & Ericson2017).

The negative effects of late enrolment also spread to the rest of the children because of 'age-for-grade' heterogeneity factors. 'Age-for-grade' heterogeneity is when children of various ages are placed in the same grade in school (Sunny et al. 2017). This inadvertently happens when the age of entry into formal education is not properly regulated. Although Jones (2016) argues that such a set-up does not have an effect on pupils' learning, but there is evidence on the contrary. Such learning environments are fertile grounds for juvenile delinquencies like bullying (Jan & Husain 2015). According to World Youth Report (2003), juvenile delinquency is rife when children survive in difficult conditions. In the case of classes of age-heterogeneity, the conditions can be difficult for both the young ones and the older ones.

The foregoing section pointed to the high school non-completion rate in children who enrol late for formal education. As if this is not bad enough, their dropping out of school can influence their younger friends to drop out as well. This works out in a domino effect as dropping out will be seen as the norm (Bhagavatheeswaran et al. 2016). The primary schools' dropout rate also affects countries' chances of attaining universal primary education. For universal primary education to be achieved, all children must have completed a full course of primary education (The Africa-America Institute 2015). As such, there is a need to curb factors that disturb the continued stay of children in school so as to curb this domino effect brought by age-heterogeneity.

Besides the issue of dropping out of school, the 'clutch-the-ear' maturity prediction method can be linked to stereotypes and discrimination. Social stereotypes are simplified and generalised beliefs about individuals or groups (Cox et al. 2012). Stereotypes, in this instance, occur as people label those who will have failed to pass the 'maturity' test the same time with their age-mates as failures. This instigates general stereotyping on those withbelow average height. Stereotyping has a long-term effect on the affected. 'Researchers have found that stereotypes affect attitudes, emotions, and behaviours' (Cuddy et al. 2007). Intrinsically, practices that lead to such stereotypes and discrimination need to be outlawed.

Conclusion

There are positive facets of the IKS intelligence that need to be preserved and incorporated into modern systems. 'African indigenous knowledge systems are critical components in the quest for the provision of quality education for all' (Sithole 2016). The 'clutch-the-ear' practice coined and presented herein has its weaknesses but exposes some valuable attributes that an education system must embrace from the IKS. As explained, the system is a pinnacle of transparency. It is free from manipulation. There is a need to preserve, not the method as it were, but those attributes to the modern education system. There is a need for transparency and consistency in the enrolment system. Systems that require merit for enrolment must use objective measures without manipulation and biases. This will eliminate the social construction that comes with subjectivity (Brickell 2006). Authorities must ensure that enrolment is based on age for those levels where placement of children by age is crucial. This will ensure that the systems work for the good of all in terms of eradicating prejudice.

The negative effects of the practice as discussed above revolve around age-for-grade disparities, stereotypes and discrimination. The subsequent grade-age-heterogeneity becomes rife when the maturity predictor is not objective. However, for educational development, the main concern must not be on the utility of this practice per se, but on eliminating conditions perpetuating problems. It is evident from literature that, lamentably, some children are getting enrolled late into school. The IKS has been utilised herein to expose the possible prevalence of practices and perceptions that need to be worked on for the full utilisation of educational development initiatives to be in place to occur. The discussion has shown the negative effects of age-for-grade discrepancies in the discussions on juvenile delinquencies. In terms of disability, it is evident that there is an interaction between the societal practices and what obtains biologically. This is because the social arrangements and practices can make biological conditions more relevant (Wendell 1996). There is already evidence that the child living with disabilities has two to three times' greater chances of not being in school in Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe (UNESCO 2008). In this case, classical measuring of maturity further inconveniences those living with disabilities by reducing their chances of accessing basic education.

Scholars on IKS must make a positive and unbiased criticism rather than mere veneration for the sake of it. There are scholars who are doing justice in their work and ought to be emulated. De Beer and Whitlock (2009) and De Vynck, Van Wyk and Cowling (2016) have made strides in using scientific methodologies to interrogate IKS, a move that brings objectivity to IKS scholarly work. The former utilises scientific methods of inquiry in life sciences IKS, whilst the later have applied scientific inquiry to botany IKS studies. These researchers also plan to take such scientific approaches in future IKS work. In sociological IKS inquiries, Zungu (2016) presents an arguably unbiased research explaining the rampant perpetuation of women subordination and male domination through chores and unequal treatment as reflected in Zulu proverbs. In a number of cited proverbs, women are presented as inferior humans. The proverbs talk of girls having to know from early years that they should solely aim at getting a good suitor and thereafter become housewives. 'Society perceives men as intelligent in conflict resolution and skilled in societal disputes' (Zungu 2016:221). It is through such socialisation and teachings rife in IKS that the 'gendered' depiction of women in society is perpetuated. This shows that social construction of knowledge is very rife in IKS. As such, there must be sincere effort to speak against it through unbiased presentations.

This article also has a recommendation for policy-makers dealing with increasing enrolment of children into schools. The authors note, with appreciation, proposals already in literature: to implement cost-cutting and demand stimulating or financial measures over and above the construction of more schools and existing ones (Bredie & Beeharry 1998). The Centre for Global Development (2002) suggests economic support for poor households as done in Mexico, back-to-school programmes as done in Angola and increased investments in education as done in Korea as ways to increase enrolment. This article recommends a 'backward-integration-enrolment' strategy in which schools will go into the communities and enrol children as opposed to waiting to enrol those brought to them. By so doing, schools will take modern measures to the people and timely enrol the children at source rather than waiting while the damage will be going on.

Finally, the argument presented in this article is that although the African system is rich in non-conventional ways of measuring, there are practices that need to be abandoned. Practices like measuring maturity through asking children to clutch their ears are, by and large, inadequate and defective. There is need to protect that which is good and pluck out that which is defective on the basis of impact to the society not merely protect for the sake of identity. In terms of educational development, there is a need to ensure timely access to all. The final aim is that 'though equality of educational opportunity may not guarantee an equal outcome in life chances, it does require that the process leading to the achievement and attainment be fair' (Jia & Ericson 2017:97).

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships which may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

The idea to investigate this phenomenon came from F.R.Z., the lead researcher, who then consulted K.M. for better insights from someone currently practising as a secondary school teacher. A.C. then came in as being the lead researcher's usual partner in research, especially on conceptual issues. The three then put together the brainstorm ideas which laid the foundation for the theoretical framework and methodologies to use. F.R.Z. handled the drafting issues; K.M. and A.C. worked on the proofreading and aligning of ideas. The submission task was taken up by F.R.Z. as the corresponding author. All parties contributed in attending to reviewers' inputs.

References

Airoboman, F.A. & Asekhauno, A.A., 2012, 'Is there an 'African' Epistemology?', Jorind 10(3), 13-17. [ Links ]

Baloyi, L. & Ramose, M.B., 2016, 'Psychology and psychotherapy redefined from the viewpoint of the African experience', Alternation 18, 12-35. [ Links ]

Berger, P.L. & Luckman, T., 1966, The social construction of reality, Penguin Books, London.

Bhagavatheeswaran, L., Nair, S., Stone, H., Isac, S., Hiremath, T., Raghavendra, T. et al., 2016, 'The barriers and enablers to education among scheduled caste and scheduled tribe adolescent girls in northern Karnataka, South India: A qualitative study', International Journal of Educational Development 49, 262-270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2016.04.004 [ Links ]

Branson, N., Hofmeyer, C. & Lam, D., 2014, 'Progress through school and the determinants of school dropout in South Africa', Development Southern Africa 31(1), 106-126. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2013.853610 [ Links ]

Bredie, W.B. & Beeharry, G.K., 1998, School enrolment decline in sub-Saharan Africa: Beyond the supply constraint, World Bank Publications, Washington, DC.

Brickell, C., 2006, 'The sociological construction of gender and sexuality', The Sociological Review 54(1), 88-113. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2006.00603.x [ Links ]

Centre for Global Development, 2002, Rich world, poor world: A guide to global development, viewed 20 May 2017, from https://www.cgdev.org/files/2844_file_EDUCATON1.pdf

Cox, W.T.L., Abramson, L.Y., Devine, P.G. & Hollon, D., 2012, 'Stereotypes, prejudice and depression: The integrated perspective', Perspectives on Psychological Science 7(5), 427-449. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1745691612455204 [ Links ]

Cuddy, A.J.C., Fiske, S.T. & Glick, P., 2007, 'The BIAS map: Behaviours from intergroup affect and stereotypes', Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 92(4), 631-648. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.4.631 [ Links ]

DeBeer, J. & Whitlock, E., 2009, 'Indigenous knowledge in the life sciences classroom: Put on your deBono Hats', The American Biology Teacher 71(4), 209-216. https://doi.org/10.1662/005.071.0407 [ Links ]

Delprato, M.A., Akyeampong, K. & Dunne, M., 2017, 'Intergenerational education effects of early marriage in sub-Saharan Africa', World Development 91, 173-192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.11.010 [ Links ]

De Vynck, J.C., Van Wyk, B.E. & Cowling, R.M., 2016, 'Indigenous edible plant use by contemporary Khoe-San descendants of South Africa's Cape South Coast', South African Journal of Botany 102, 60-69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2015.09.002 [ Links ]

Dickson, A.A. & Mbosowo, M.D., 2014, 'African proverbs about women: Semantic import and impact in African societies', Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 5(9), 632-641. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n9p632 [ Links ]

Ganira, K.L., Inda, A.N., Odundo, P.A., Akondo, J.O. & Ngaruiya, B., 2015, 'Early and forced child marriage on girls' education, in Migori County, Kenya: Constraints, prospects and policy', World Journal of Education 5(4), 72-80. https://doi.org/10.5430/wje.v5n4p72 [ Links ]

Government of Zimbabwe/United Nations Country Team, 2010, Country analysis report for Zimbabwe, viewed 20 May 2017, from http://zw.one.un.org/sites/default/files/Country%20Analysis%20Report%20for%20Zimbabwe%202010.pdf

Heymann, J., Raub, A. & Cassola, A., 2014, 'Constitutional rights to education and their relationship to national policy and school enrolment', International Journal of Educational Development 39, 131-141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2014.08.005 [ Links ]

Heyneman, S.P. & Lee, B., 2016, 'International organizations and the future of education assistance', International Journal of Development 48, 9-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2015.11.009 [ Links ]

Honderich, T., 2005, The Oxford companion to philosophy, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Jan, A. & Husain, S., 2015, 'Bullying in elementary schools: Its causes and effects on students', Journal of Education and Practice 6(19), 43-56. [ Links ]

Jia, Q. & Ericson, D.P., 2017, 'Equity and access to higher education in China: Lessons from Hunan province for University admissions policy', International Journal of Educational Development 52, 97-110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2016.10.011 [ Links ]

Jones, S., 2016, 'How does classroom composition affect learning outcomes in Uganda primary schools?' International Journal of Educational Development 48, 66-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2015.11.010 [ Links ]

Kahyana, D.S., 2016, 'Depiction of African indigenous education in AkikiNyabongo's Africa Answers back (1936)', Alternation 18, 241-254. [ Links ]

Kamanda, M., Madise, N. & Schnepf, S., 2016, 'Does living in a community with more educated mothers enhance children's school attendance? Evidence from Sierra Leone', International Journal of Educational Development 46, 114-124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2015.09.008 [ Links ]

Kasnitz, D. & Shuttleworth, R.P., 2001, 'Anthropology in disability studies', Disability Studies Quarterly 21(3), 2-17. https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v21i3.289 [ Links ]

Mallon, R., 2007, 'A field guide to social construction', Philosophy Compass 2(1), 93-108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-9991.2006.00051.x [ Links ]

Masino, S. & Niño-Zarazúa, M., 2016, 'What works to improve the quality of student learning in developing countries?' International Journal of Educational Development 40, 53-65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2015.11.012 [ Links ]

Nobles, W.W., Baloyi, L. & Sodi, T., 2016, 'Pan African humanness and SakhuDjaer as Praxis for indigenous knowledge systems', Alternation 18, 36-59. [ Links ]

Nonoyama-Tarumi, Y., Loaiza, E. & Engle, P.L., 2010, 'Late entry into primary school in developing societies: Findings from cross-national household surveys', International Review of Education 56(1), 103-125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-010-9151-2 [ Links ]

Ocitti, J.P., 1973, African indigenous education as practiced by the Acholi of Uganda, East African Literature Bureau, Nairobi.

Olanrewaju, R.A., 2016. 'Backward integration: A panacea for rural development in Nigeria', Academic Journal of Economic Studies 2(4), 38-56. [ Links ]

Özcebe, H. & Biçer, B.K., 2013, 'An important female child and women problem: Child marriages', Turk Arch Ped (48) 86-93. https://doi.org/10.4274/tpa.1907

Psaki, S.R., 2014, 'Addressing early marriage and adolescent pregnancy as a barrier to gender parity and equality in education', Background paper for the 2015 UNESCO education for all global monitoring report, Population Council, New York.

Pufall, E., Eaton, J.W., Nyamukapa, C., Schur, N., Takaruza, A. & Gregson, S., 2016, 'The relationship between parental education and children's schooling in a time of economic turmoil: The case of east Zimbabwe, 2001-2011', International Journal of Development 51, 125-134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2016.09.003 [ Links ]

Ramose, B.M., 2016, 'But the man does not throw bones', Alternation 18, 60-71. [ Links ]

Reid-Cunningham, A.R., 2009, 'Anthropological theories of disability', Journal of Human Behaviour in the Social Environment 19, 99-111. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911350802631644 [ Links ]

Scott, J. & Marshall, G.A., 2009, A dictionary of sociology, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Sithole, M., 2016, 'Opportunities of incorporating African Indigenous Knowledge Systems (AIKS) in the physics curriculum', Alternation 18, 255-294. [ Links ]

Soropa, G., Gwatibaya, S., Musiyiwa, K., Rusere, F., Mavima, G.A. & Kasasa, P., 2015, 'Indigenous knowledge system weather forecasts as a climate change adaptation strategy in smallholder farming systems of Zimbabwe: Case study of Murehwa, Tsholotsho and Chiredzi districts', African Journal of Agricultural Research 10(10), 1067-1075. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJAR2013.7205 [ Links ]

Sunny, B.S., Elze, M., Chihana, M., Gondwe, L., Crampin, A.C., Munkondya, M. et al., 2017, 'Failing to progress or progressing to fail? Age-for-grade heterogeneity and grade repetition in primary schools in Karonga district, northern Malawi', International Journal of Educational Development 52, 68-80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2016.10.004 [ Links ]

The Africa-America Institute, 2015, State of education in Africa Report, viewed 20 May 2017, from http://www.aaionline.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/AAI-SOE-report-2015-final.pdf

UNESCO, 2007, EFA global monitoring report 2008, Education for all by 2015: Will we make it?, United Nations Education, Science and Cultural Organization, Paris.

UNESCO, 2008, Regional overview: Sub-Saharan Africa, viewed 20 May 2017, from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0015/001572/157229e.pdf

UNESCO, 2010, Education for all global monitoring report, viewed 20 May 2017, from http://en.unesco.org/gem-report/sites/gem-report/files/gmr2010-fs-ssa.pdf

UNICEF, 2012, Ghana country study: All children in school by 2015, viewed 20 May 2017, from http://www.uis.unesco.org/Library/Documents/out-of-school-children-ghana-country-study-2012-en.pdf

UNICEF, 2016, Zimbabwe country case study: Improving quality education and children's learning outcomes and effective practices in the Eastern and Southern Africa region, viewed 20 May 2017, from https://www.unicef.org/esaro/ACER_Report_Zimbabwe_CS.pdf

United Nations, 2016, Sustainable development goals report, viewed 23 March 2018, from https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2016/

Wendell, S., 1996, The rejected body, Routledge, New York.

Wils, A., 2004, 'Late entrants leave school earlier: Evidence from Mozambique', International Review of Education 50(1), 17-37. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:REVI.0000018201.53675.4b [ Links ]

World Bank, 2003, Achieving universal primary education by 2015: A chance of every child, World Bank, Washington, DC.

World Youth Report, 2003, Juvenile delinquency, viewed 20 May 2017, from http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unyin/documents/ch07.pdf

Zuesse, E.M., 1975, 'Divination and deity in African religions', History of Religion 15(2), 158-182. https://doi.org/10.1086/462741 [ Links ]

Zungu, E.B., 2016, 'Defining feminine roles: A 'gendered' depiction of women through Zulu proverbs', Alternation 18, 221-240. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Felistas Zimano

zimanof941@gmail.com

Received: 30 June 2017

Accepted: 27 June 2018

Published: 25 Sept. 2018