Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Childhood Education

versión On-line ISSN 2223-7682

versión impresa ISSN 2223-7674

SAJCE vol.8 no.1 Johannesburg 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v8i1.511

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Service-learning through Art Education

Georina Westraadt

Faculty of Education, Cape Peninsula University of Technology, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Intermediate Phase students in the Bachelor of Education programme who elect art as one of their majors often experience problems in the teaching of art at schools during teaching practice. To overcome this problem, a service-learning project was designed by which students were granted the opportunity to teach art to children from a children's home. This project proved to be a valuable component in curriculum studies in the fourth year of Art Education. To determine in which way and to what extent art lessons contribute to the development of children and students, a case study was conducted. Data were obtained from studying their conduct and the results of their work. Additional data were drawn from interviews with caregivers at the home and discussions with children to determine to what extent art classes had an effect on their lives. Student evaluations and interviews upon completion of the project provided data which emphasised the reciprocal nature of this service-learning project. Considering the data, inferences can be drawn about the value of service-learning to learners and students, accompanied with suggestions for the future development of the project.

Introduction

Teaching practice is an important aspect of learning for teachers in training. When students visit schools for teaching practice, they are confronted with varying circumstances. Because of their substantial teaching practice assignments, it is often difficult to fit in all the subjects they need to teach. In many cases, class teachers are not keen to allow them time to teach art, despite it being a compulsory part of the school curriculum. This lack of teaching time is a problem for students in the Bachelor of Education (B Ed) intermediate and senior phases who elect Art Education as one of their majors: students seldom have the opportunity to practise the didactics of their major subjects with learners in real-life situations at schools.

To overcome this obstacle, a service-learning project was designed by which fourth year B Ed students with Art Education as major gained the opportunity to teach art to a group of children from a nearby children's home, who came to the campus in the afternoon for art lessons. Initially, the institution's service-learning policy and procedure of the Centre for Community Engagement and Work Integrated Learning was consulted. Application was made for the project to be registered, with accompanying budget of expenditure and contract with the children's home.

Research methodology

A descriptive case study enquiry was conducted to answer two research questions:

1. How does service-learning in art contribute to the holistic development of Intermediate Phase learners?

2. What is the effect of service-learning on the learning of students with Art Education as major for their fourth year of study?

One group of participants in the study were six children from a local children's home, who attended weekly art lessons on campus, and their caregivers at the home. The lessons formed part of a service-learning project. The other participants in the study were four B Ed 4 I/SP (Intermediate Phase) students with Art Education as one of two major electives for their degree.

Theoretical framework for the study

Freire's co-intentional education theories apply to service-learning theory and pedagogy. Freire (1970:60-61) believes that 'committed involvement' was essential in an education that valued both teachers and learners as active participants in the teaching and learning process. Freire looks at teachers and pupils as co-learners or co-workers who work together towards mutual goals of social justice and personal transformation. This reciprocity is a crucial aspect of service-learning theory: constant and meaningful exchange between all parties involved are critical for mutual respect, values, needs and expectations (Taylor 2005:582).

Literature review

Prior to the study, literature on service-learning was reviewed. According to Lazarus et al. (2008:62), service-learning is defined as an educational experience by which students partake in an organised service activity in a specific community. The project forms part of their course, counts towards their assessment and meets the needs of a community. Participation in the project assists in their understanding of the course content and leads to a broader appreciation of the discipline and an enhanced sense of personal values and civic responsibility. This definition reinforces the importance of reciprocity with the community and reflection by the students and emphasises civic learning outcomes as key (Hatcher & Erasmus 2008:50). Prentice and Robinson (2010:1, 2) define service-learning as the combination of community service with academic instruction, focusing on critical, reflective thinking and personal and civic responsibility. Service-learning provides students with experiences that link course content with skills to impart that knowledge to learners. Service-learning is reciprocal learning by which everyone is in service and everyone can learn (Stanton & Erasmus 2013:67).

In South Africa there has been a growth in service-learning since 2000, which was originally initiated by the Joint Education Trust (JET), through the Community Higher Education Service Partnership (CHESP) initiative (Lazarus et al. 2008:57). At the inception of the CHESP initiative in South Africa, the JET reinforced aspects of this definition in programme documents by stating that service-learning is a 'thoughtfully organized and reflective service-oriented pedagogy' and added that it is:

focused on the development priorities of communities through interaction between, and application of, knowledge, skills and experience in partnership with community, academics, students, and service providers within the community for the benefit of all participants (JET 2001:94).

The African National Congress (ANC) government's Ministry of Education issued the Education White Paper 3, in which 'A Programme for Higher Education Transformation' was outlined. The white paper called for transformation within the education sector, in terms of maximising its engagement with, and contributions to, the resolution of the complex issues that an emergent South Africa faced internally after years of systematic, external isolation. Higher education institutions were called upon to 'demonstrate social responsibility and show their commitment to the common good by making available expertise and infrastructure for community service programmes'. The white paper stated that a major goal of higher education should be to 'promote and develop the social responsibility and awareness amongst students of the role of higher education in social and economic development' (Stanton & Erasmus 2013:74). Stanton and Erasmus (2013:79) discuss how staff of the JET and CHESP worked with the South African Department of Education to develop policy guidelines that would encourage community engagement. They worked with the Higher Education Qualifications Authority to develop criteria for assessing institutional progress to implement a pilot service-learning project at national, institutional and programmatic levels.

Service-learning in Art Education

Taylor (2002:124) proposed service-learning within Art Education 'as a transformative and socially reconstructive practice' emphasising the reciprocal learning experience that is possible through service-learning. Because of the social character of service-learning, and the emotional challenges inevitably faced by the participants, it is a natural means to nurture social and emotional learning (Russell & Hutzel 2007:7).

Washington (2011:270) feels that out-of-school settings can provide an environment for art teachers to experiment with new types of learning relations. Such sites provide ample room for refinement of art teaching practices that include a greater emphasis on the growth of relations, social structures and culture. Art teaching and learning uncovers new ways to address community problems or concerns when the objectives of our work include paying attention, responding, making connections and learning (Washington 2011:272).

Russell and Hutzel (2007:8) describe three characteristics of service-learning in Art Education:

1. It is part of the art curriculum. Service-learning is a planned unit in the art curriculum. The lecturer supports and participates in the planning and implementation of the activity, which is critical for educational integrity.

2. Students serve and learn, and pupils benefit and learn because of their involvement.

3. Involvement in service-learning extends student learning.

Service-learning and art classroom management

Art room management and learner behaviour often pose problems that affect the quality of learning in art. Research in classroom management clarifies the need for stimulating and successful learning in an emotionally secure setting (Jones & Jones 2004:282-283). Good art teaching includes creating conditions for effective learner behaviour. Responsible pupil behaviour should be taught specifically and directly to children, like any other subject in the curriculum, not conditionally managed.

Lampert (2007:268) believes that pre-service teachers are often concerned with art classroom management: they prepare for work in the Intermediate Phase. Many students have voiced concerns about a lack of experience in managing learners: in some cases, children call out responses meant to get a laugh, or they laugh loudly at another child's answer. In service-learning all stakeholders work together in the after-school art programme, in which students gain experience in the formulation of a classroom management system that addresses the special requirements of art classroom management.

Service-learning and children at risk

Children from an institution such as a children's home were removed from their parents' homes for valid reasons. Although they are well cared for at the home, it was evident that some of the learners were experiencing emotional or learning problems; methods had to be designed to calm the atmosphere in the after-school programme which was often disruptive. Often, at the schools attended by these children, their timetable does not offer an art component. Quality after-school programmes can provide hope for these children. It offers structured activities for the youth, providing constructive interactions with adults who can serve as role models. The creation of art classes fosters a sense of belonging, success and creativity. Children can develop positive relations with peers and adults and be engaged in meaningful activities during after-school art programmes (Shepard & Booth 2009:15).

Phases in service-learning

According to Russell and Hutzel (2007:10), successful service-learning requires the following phases:

1. Planning, setting goals and analysing situations: Students work with the lecturer to plan the project as a curriculum unit. Students assess issues of time and materials and the creation of artwork. Short- and long-term objectives are considered.

2. Assessment and reflection: Methods for assessment and reflection can include student journals, group discussions and personal interviews.

Assessment and service-learning

In South Africa academic credits are not awarded for engaging in community service, but rather for the academic learning that occurs and is demonstrated as a result of the community service experience (Hatcher & Erasmus 2008:50). Prentice and Robinson (2010:14) recommend ways other than the traditional grade point average in the assessment of service-learning.

In the art and service-learning study, student learning was assessed in relation to their participation and by means of an end-of-course survey. The student voice in this study validates the benefits of the service-learning pedagogy as an active, engaged method of learning skills and knowledge which is important beyond graduation. Lampert (2007:265-266) describes how a service-learning project closed the gap between the role of observer and the real-life situation in the evaluation of students teaching art to primary school children.

Data for the Art Education service-learning project

Data collected for this study came from the children, their caregivers and from the students who taught them art.

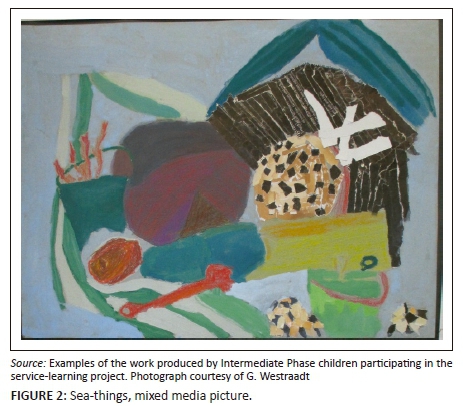

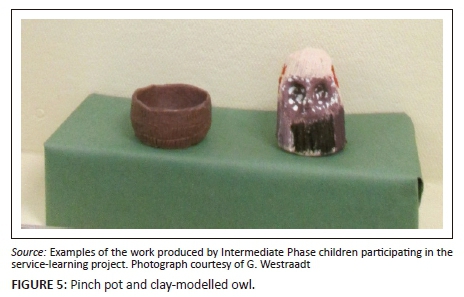

Field notes recorded observations of the children's conduct and working methods during the art lessons, from the first to the last session of the programme. An important source of data was the examples of the completed works done by the children, which comprised two- and three-dimensional practical work. The learners' work was mounted and exhibited at the annual student exhibition, and children were invited guests at the opening, where they each received a bag containing art materials, supplied by the service-learning unit of the university.

The service-learning programme, which ran from May to October, included a visual literacy lesson where the children looked at, and discussed art elements in the work done by a well-known South African artist. Students wanted to assist children in developing an awareness of the elements of art. The work of Maggie Laubser was chosen, which would acquaint the children with the multiple ways artists create their views of the world.

Another source of data was made up of recorded informal interviews with children at the end of the programme. During the interviews, questions were asked about their experience of the art making and appreciation lessons. A final source of data was discussions with the caregivers at the children's home, in an attempt to glean information about the effect of the programme on the school marks, and general development and behaviour of the children.

The students followed the phases in service-learning, such as planning and situation analysis, while working with the lecturer to pay attention to the logistics of the project as a curriculum unit. Students had to work out a timescale, plan the use of media for the creation of the artwork and determine factors that might influence individual responses from learners. Short- and long-term objectives were considered.

The students knew that their time invested in the service-learning project was possibly the most important experience they would have in their teacher training. The reciprocal learning experience that they experienced through service-learning was evident during the reflection and group discussions held after lessons. These discussions were captured in journals which they kept for reference. The student voice in this study validates the benefits of service-learning pedagogy as an engaged method of learning skills and knowledge which is relevant and beneficial beyond graduation (Prentice & Robinson 2010:14).

Assessment and reflection took place the day after the lesson was taught to the children, in the form of a class discussion, after viewing the DVD of the student in action, as well as analysis of the children's artwork. The competencies and skills that needed to be developed were considered when following sessions were planned. Students' marks after assessment of the project reflected the seriousness with which students approached their work with the children. Students were asked to evaluate the project using the service-learning evaluation sheets adapted for the Art Education project. Evaluations were used as data to measure the success of the project for the students' learning.

To comply with the institution's service-learning policy and to reiterate the description of the characteristics of service-learning in Art Education by Russell and Hutzel (2007:8), the project formed part of the Art Education curriculum as a planned, credit-bearing unit.

Ethical considerations

Prior to the research, written permission was obtained from the head of the children's home to collect data by means of observation of their work as well as from interviews with the caregivers and the children. The undertaking was that the identities of the children would not be revealed in the study and that no information that could lead to their identification would be divulged. The caregivers consented to be participants in the interviews and the children were asked permission for their answers to the questions about the project to be recorded. Ethical clearance was obtained from the university. Students involved signed a letter of consent for their reflections and assessments to be used as data for the study.

Results of the research

To answer the two research questions, data obtained with regard to the children's development were transcribed from field notes, the photographs of the work that the children produced and the interviews with children and caregivers. Added to this were data that emerged from student reflection, DVD recordings of students in action and final assessment of the project. These sources provided rich data which were categorised into themes and sub-themes for analysis. These themes addressed the holistic development of the children and students' learning after termination of the service-learning.

The first set of data extracted from the field notes on the conduct and work methods of the children is discussed briefly.

It was observed that with many of the projects, students reported that children did not pay attention to initial introductory explanation and often needed individual re-explanations. They had trouble carrying out instructions. There was evidence that they worked on a small scale and wanted to cover up their work; they often laughed at their own efforts and those of other children. On some days, the children were more restless than at other times. The following remarks were recorded during a drawing session:

-

Child A, a grade 6 boy plays and fidgets, turning the page in different directions all the time, drawing the same line over and over, looking at the other children's work, trying to copy that. He replaces the pastel from right to left hand, working slower with the left hand.

-

Child B, a grade 6 girl battles with the placing of the objects on the page, does not really concentrate or try to make it work.

-

Child C, a grade 5 girl turns the page in different directions, uncertain about right or left dominance.

In spite of a thorough explanation by the student, during which children were encouraged to work slowly and to think about the lines they drew, they often scribbled, working scratchily and roughly. It was noted that they fidgeted, made strange sounds and did not concentrate, or had short concentration spans. They were afraid to dare and constantly needed assistance, especially in the mixing of paint to create different shades. Although the lessons were carefully planned and elementary for this age group, they posed several challenges to the children. This was a valuable learning experience for the students when it came to decisions about subject-matter for picture-making lessons: students learnt that it sometimes requires re-thinking and adjusting preliminary ideas to match the abilities of learners.

The next set of data was extracted from the children's art. Some examples produced by the children are discussed.

When the examples of their work were mounted and exhibited, it was evident that there was a remarkable growth and progress in the work the children produced in the drawing project, as can be seen in Figure 1.

The children gradually managed to grasp and pay attention to the explanations and eventually completed their projects, as is evident from the following figures of the picture-making project, a collection of 'sea-things' such as a spade, shells, a hat, a ball and so forth (Figure 2), followed by a later picture by the same learner, of himself playing ball (Figure 3).

It is evident from Figures 2 and 3 that this learner gained control over the medium and successfully filled the picture plane in an aesthetically successful sensible way. There is evidence of control of the media and successful portrayal of the human figure in the context of playing sport.

The students gained considerable insight in the design of lessons for this age group, as is evident from the fact that the latter picture (Figure 3) was a more manageable topic. It posed less of a challenge and all the children were able to complete the project with less disruption and problems. The significance and pedagogical import of careful consideration of the choice of topics for diverse groups of children became clear to students.

Examples of the work of a girl who experienced particular problems with the placing, utilisation of the picture plane and left or right dominance illustrate this point. It is clear that she still drew the human figure, herself, not being able to stretch the legs to reach the bottom of the page (Figure 4).

The next set of data was extracted from interviews with the children and is discussed briefly.

All the children were asked if it would be in order to record their replies to the interview questions. They were willing to talk about their experiences of the art lessons. A student came in with the children to make them feel comfortable. The evident answers, namely that they were proud of their work, revealed that they looked forward to art every week, that it made them feel good and that they had learnt new things. When asked what kind of things, one learner, a grade 6 girl explained:

'Ek sukkel by die skool met Wiskunde en Engels. Die Kunsklasse het my kalm gemaak toe kon ek meer luister in die klas. Dit het my ook gehelp met Afrikaans want ek het nuwe woord geleer en ek moes mooi luister vir die juffrou'. ['I have trouble at school with Maths and English. The art made me feel calm, and then I can concentrate better. It helped me with Afrikaans (their language), because I learned new words and I had to listen to the teacher.'] (Grade 6 learner, female, 11 years old [Authors own translation translation]).

Another learner, a grade 6 girl commented about the art lessons:

'Die kuns het my gehelp met my Aardrykskunde. Ons moet teken in Aardrykskunde, kaarte en ander goed wat ons lees en dan moet ons dit teken. Die kunslesse het my baie daarmee gehelp. Dit het my ook gehelp met Afrikaans. Ek kan nou beter oplet en ek ken nou meer woorde.'

[It helped me with Geography. We have to draw in Geography, maps and things that we read and then we must draw it. The art lessons helped me a lot with that. It also helped me with Afrikaans. I can concentrate more and I know more words now] (Grade 6 learner, femal 12 years old [Authors own translation translation]).

The majority of the children said that the clay work (Figure 5), the modelling of a barn owl, was the most enjoyable and that they looked forward to that the most. Looking at the art of real artists was another part of the course which the children commented on as meaningful, adding to their vocabulary, and understanding and enjoyment of art.

The following set of data emerged from interviews with the caregivers:

At the home, there is a caregiver, acting as 'mother' for 10-12 children. She stays with them in a house and is involved in the lives of all the children in her care. The children vary from 2 to 16 years of age. The caregivers were interviewed at the home. They were willing to participate in the study and consented to the use of their reports for the research.

These interviews highlighted increased concentration, improvement in marks and a raised confidence, evident from the children as the art project progressed during the year.

A female caregiver from the children's home reported as follows:

'Die kinders was elke week opgewonde en wou graag na die kuns toe gaan. Die klasse het struktuur en hulle het nodig om veilig te voel in 'n goed beheerde omgewing. Baie van die kinders is aandag afleibaar en die individuele aandag wat die studente aan hulle gee by die kunsklasse het hulle gehelp met van hulle probleme om op te let. Hulle kuns kom van binne, hulle druk hulleself so uit.'['The children were excited and motivated every week before they went to art. It is structured and they need that as they feel safe within a controlled environment. Many of the children suffer from ADHD and the individual attention from the students during art helped them to overcome some of their attention problems. The expression really comes from within them.'] (Caregiver 1, female, caregiver at children's home, [Authors own translation translation])

A female caregiver from the children's home reported as follows:

'Die kuns werk positief in op ons huis. Hulle werk is gelamineer en teen die mure opgesit en dit laat die huis mooi lyk. Ander is daardeur geïnspireer, selfs kinders wat nie kuns toe gegaan het nie, het die huis begin mooimaak. Die kinders se skoolpunte het opgegaan van April af, hulle kan langer konsentreer en sien fyner dinge raak.' ['The art had such a positive impact in their house. They laminated their work and put it up on the walls to beautify the place. Others were inspired by that and even the children who did not go to art, became involved in decorating the house. Learners' school marks showed an improvement since April, they have a longer concentration span and observe more detail.'] (Cargiver 2, female, caregiver at children's home [Authors own translation translation])

A female caregiver from the children's home reported as follows:

'Die kinders geniet die kunsklasse want hulle leer dinge waarvan hulle hou. Dit maak hulle sterker en hulle sien uit daarna om te gaan en leer elke week iets nuut. Hulle kom terug, so trots op hulle werk, veral die kleiwerk. Dit is iets nuttig wat hulle doen. Hulle punte het verbeter, een kind het die eerste twee kwartale gedruip, maar die laaste kwartaal geslaag. Hulle was so trots op hulle uitstalling en dat hulle die spesiale gaste wat by so 'n belangrike aandfunksie.' ['The children enjoy the lessons as they learn through something that they like doing. This strengthens the learners and they look forward to going and learning something new every week. They were very proud of their work, especially the clay work. This is something very useful that they are doing. School marks have improved; one child failed the first two terms, but passed in the final term. They were extremely proud of the exhibition and that they were invited guests at an important evening function.'] (Caregiver 3, female caregiver, caregiver at children's home. [Authors own translation translation])

The final source of data was the student reflection and evaluations of the service-learning project.

Reflections upon termination of the project revealed how students experienced the project. They were informed about the project early in the year and started to prepare lessons under the lecturer's guidance timeously. They had individual tasks, especially when it was their turn to teach, but worked on the project as a group. The lessons were considered carefully and planned as a group during weekly sessions, led by the lecturer. The students were certain about all the lessons and the media to be used in each lesson. The lecturer guided them but students were encouraged to give their opinion and make suggestions for improvement of the lessons.

The students' learning was enhanced as they had the opportunity to practise teaching skills and identify the areas in which children experienced difficulties. They learnt to present art to a group and make adjustments to presentation techniques. Prior to the discussion after each lesson presentation, the groups watched and discussed the DVD recording of the student in action. Viewing the recordings revealed that one student in the group, when she saw the children struggling, knowing their background and where they came from, became too involved and wanted to do too much to help them succeed. This led to a dependency problem, often evident in children from children's homes. After a discussion in the group, the situation was corrected and this student learnt to step back and allow for experiential and discovery learning, which were the initial aims of the project.

The students had to meet children at their level and proceed from there. Students needed to learn to become part of the larger whole, devising new ways of teaching and different approaches to meet the needs of the children. Students had to recall and use their knowledge of didactics of Art Education and implement what they had learnt during their 3 years of study. Knowledge of, and skills needed for, Art Education was put into practice: students helped the children develop skills. The students acquired new skills of lesson presentation and had to overcome certain boundaries because they had to explain art procedures well and give individual attention and encouragement because many of the children were slowed down by one or another form of learning hindrance. The group learnt from each other, co-operated and supported one another while working together and assisting one another. They gained patience and had to think on their feet about how to deal with unexpected situations and especially how to motivate learners to believe in their own ability to create.

The lecturer prepared them for dealing with the children from the children's home and communicated the social issues involved, so that they felt adequately equipped. They were able to connect with the children and treat them with respect.

The group had a discussion after every lesson, and the lecturer guided and assisted them when certain strategies did not work well. The lecturer helped them to overcome stumbling blocks. Successes were examined. It was clear that children developed as their skills improved. Students were of the opinion that the project was a success because the children's work and conduct improved.

Discussion

The conduct and work methods of the children that attended the service-learning in art posed challenges to the students: learner behaviour sometimes required strict discipline, reprimands, individual attention and encouragement. At some stage, interventions had to be designed with the assistance of the lecturer. This is a valuable learning experience for students because they become aware that an art classroom warrants a different form of management, something that they were not able to acquire in the true sense during the teaching practice period before.

The work that the children produced clearly illustrates their initial struggle to manage the media and to pay attention to the explanations. However, as the project progressed, their work improved and eventually their development could be confirmed when viewing the exhibition of their art. Because of this progress, they gained confidence in their own ability, applied themselves in a more concentrated manner to the lessons and produced improved results. This improved self-concept made them feel worthy and had the added benefit of improving their schoolwork.

Discussions with the children and their caregivers emphasised the beneficial effect of the art lessons on their development, resulting in increased vocabulary, self-confidence, pride in their own attempts, and appreciation and general improvement in their school performance. Clearly visible was the enrichment of which Koopman (2005) writes, when children experience quality Art Education. Being involved in art activities gave the children a sense of fulfilment: they became happy and content because they derived pleasure from the experience, and this confidence brought about a sense of spiritual well-being.

Reflections from the students, as well as their evaluation of the project, indicated that their learning was enhanced and their knowledge of, and skills for teaching, art to Intermediate Phase children improved remarkably, far more than during the teaching practice period. This improvement was underscored in the marks they attained for Subject Didactics at the end of the project.

In conclusion, it can be stated that service-learning in Art Education was beneficial to all parties involved. It led to the holistic development of the children and contributed to the students' learning and growth as educators. Projects such as this re-enforce in a practical and demonstrable manner, the didactics of Art Education. The reach and impact of service-learning in art continued beyond the lessons taught: it shaped the lives and character of all parties involved.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the Service-Learning Unit of Cape Peninsula University of Technology for their assistance to facilitate transportation for the children.

Competing interests

The author declares that she has no financial or personal relationships which may have inappropriately influenced her in writing this article.

References

Freire, P., 1970, Pedagogy of the oppressed, The Continuum Publishing Company, New York.

Hatcher, J.A. & Erasmus, M.A., 2008, 'Service-learning in the United States and South Africa: A comparative analysis informed by John Dewey and Julius Nyerere', Michigan Journal of Community Service-Learning 15, 49-61. [ Links ]

Joint Education Trust, 2001, Community Higher Education Service Partnership Implementation Grantstrategy, viewed 04 November 2014, from http://www.chesp.org.za

Jones, V.E. & Jones, L.S., 2004, Comprehensive classroom management: Creating communities of support and of solving problems, 7th ed., Allyn & Bacon, Boston, MA.

Koopman, C., 2005, 'Art as fulfilment: On the justification of education in the arts', Journal of Philosophy of Education 39(1), 85-97, viewed 16 August 2010, from http://proquest.umi.com [ Links ]

Lampert, N., 2007, After school arts program serves as real-world teaching lab, Shannon Research Press, Virginia Commonwealth University, United States, viewed 04 November 2014, from http://iej.com.au

Lazarus, J., Erasmus, M., Hendricks, D., Nduna, J. & Slamat, J., 2008, 'Embedding community engagement in South African higher education', Education, Citizenship and Social Justice 3(1), 57-83. https://doi.org/10.1177/1746197907086719 [ Links ]

Prentice, M. & Robinson, G., 2010, 'Improving student learning outcomes with service-learning', American Association of Community Colleges 2-15, viewed 11 December 2014, from www.aacc.nche.edu/servicelearning [ Links ]

Russell, R.L. & Hutzel, K., 2007, Promoting social and emotional learning through service-learning, Art Education 60, 6-11. [ Links ]

Shepard, J. & Booth, D., 2009, 'Empowering homeless children and youth', Reclaiming Children and Youth 18(1), 121 Spring, viewed 11 December 2014, from www.reclaimjngjournal.coni [ Links ]

Stanton, T.K. & Erasmus, M.A., 2013, 'Inside out, outside in: A comparative analysis of service-learning's development in the United States and South Africa', Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement 17(1), 62-90. [ Links ]

Taylor, P.G., 2002, 'Service-learning as postmodern art and pedagogy', Studies in Art Education 43(2), 24-140, viewed 11 December 2014, from http://iej.cjb.net [ Links ]

Taylor, P.G., 2005, 'The children's peace project: Service-learning and art education', International Education Journal 6(5), 581-6, viewed 11 December 2014, from http://iej.cjb.net [ Links ]

Washington, G.E., 2011, 'Community-based art education and performance: Pointing to a place called home', Studies in Art Education: A Journal of Issues and Research 52(4), 263-77. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Georina Westraadt

westraadtg@cput.ac.za

Received: 17 Nov. 2016

Accepted: 08 Apr. 2018

Published: 18 July 2018