Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Childhood Education

On-line version ISSN 2223-7682

Print version ISSN 2223-7674

SAJCE vol.8 n.1 Johannesburg 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v8i1.518

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Imaginative play and reading development among Grade R learners in KwaZulu-Natal: An ethnographic case study

Mitasha NehaI; Peter N. RuleII

ISchool of Education, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

IIFaculty of Education, Stellenbosch University, South Africa

ABSTRACT

This article argues that imaginative play can fulfil a valuable role in the development of reading among pre-school children. It uses Feuerstein's Mediated Learning Experience as a theoretical lens and defines the concepts related to imaginative play, focussing particularly on symbolic and dramatic play. Drawing on an ethnographic case study of the reading development of four pre-schoolers, aged between 5 and 6, in their home environments in KwaZulu-Natal, it shows how imaginative play is a generative aspect of early reading in the home. It is through imaginative play that the children were able to make sense of what they had read, transfer it to other contexts and explore its implications in a child-centred way. Imaginative play can take early reading from the realms of print and digital media into those of movement, dressing-up, role-playing, visual and aural stimulation - holistic and integrative ways of 'comprehending' the text. The article concludes with a discussion of the challenges and potential pedagogical implications of the research findings.

Introduction

What can play contribute to pre-schoolers' reading development? There is a growing body of evidence that play is important in children's learning, and that children's imaginations are enormous reservoirs for their own learning (Copple & Bredekamp 2009; Hurwitz 2002). We might understand their imaginations as fecund estuaries, spawning ideas and possibilities, fed by many rivers. However, formal schooling tends to confine 'play' to the playground and to disassociate it from learning (Hughes 2009). The curriculum and assessment policy statement (Department of Basic Education 2011) document states that play should form part of a child's learning categorised as 'free play inside' and 'free play outside', with examples provided to support these categories. However, the document does not provide substantial information explaining the importance of play for a child's reading development and of integrating play in a child's daily routine. Aronstam and Braund's (2016) study indicates that educators lack personal knowledge and comprehension of the concept of play, resulting in the dearth of knowledge of how to engage unstructured play to develop the learning process. This makes teaching through the use of play difficult for many educators with the result that the tributaries of imagination, which naturally feed children's learning, are often cut off during classroom hours. In addition, there is very little research which has been performed in South Africa on play and learning among pre-schoolers (Aronstam & Braund 2016), and in particular, the links between play and early reading, by which we mean the precursor skills, attitudes and knowledge that children develop as part of their emergent literacy (Christie et al. 2014).

This ethnographic case study of three 5-year-old Grade R learners and one 6-year-old Grade R learner (he was born in the second half of the year and as a result he had to attend school a year later owing to the South African Department of Education's policy) in an Indian community in KwaZulu-Natal focused on their early reading within their family environments. It found that play, in its dramatic and symbolic forms, was an important dimension of their reading experiences. In particular, play was a crucial part of how the children made sense not only of the content of reading but also of the process and social significance of reading. The purpose of this article is to describe and explore the links among play, early reading and meaning-making that emerged from the study. We first examine the scholarship at the nexus of play, learning and reading, and introduce a theoretical framework for understanding this. We then explain the methodology adopted in this study. The findings present three vignettes that show the links between play and the development of reading, focussing particularly on understanding the content (what), the process (how) and the social significance (why) of children's reading-play. Our discussion then explores some of the pedagogical implications of the findings.

Learning, reading and play

There have been numerous studies of early and primary school reading in South Africa (Fleisch 2008; Matjila & Pretorius 2004; Pretorius 2000; Pretorius & Ribbens 2005). These have found that teachers in many schools tend to emphasise decoding, pronunciation and fluency, and reading aloud as oral performance, with little attention to comprehension and meaning-making (Pretorius 2002; Sporer, Brunstein & Kieschke 2009). This is born out in the poor performance of South African learners in the Progress in International Literacy Study (PIRLS) international reading comprehension tests of 2006 (Howie et al. 2007) and 2011 (Howie et al. 2012); and The Southern and Eastern Consortium for Monitoring Educational Quality (SACMEQ) tests (SACMEQ 2002; 2007). While there is little South African research on reading in the home environment (Land & Lyster 2011), the existing local and international scholarship points to the crucial role of parents and caregivers in children's emergent literacy in mediating and modelling reading. Crawford and Zygouris-Coe (2006:261) concur that literacy learning is often rooted in the home experience. In addition, studies in the USA show a very robust association between the amount of literacy materials (newspapers, magazines, books) present in the child's home and children's reading test scores at ages 9, 13 and 17 (Barone 2011:377; Burchinal & Forestieri 2011:86-87; Christie et al. 2014).

Regarding learning and play, a South African study in this journal (Aronstam & Braund 2016) found that teachers have little or no understanding of the pedagogy of play and they feel they have not received sufficient training in this regard. As a result, in many South African classrooms, children 'learn' by sitting still, listening and repeating, and play is excluded from formal learning (Rule & Land 2017). International research shows a vital link between learning and play (Hughes 2009; Tsoa 2008; Wood 2009). Finland, consistently the highest performing country in education, places great emphasis on structured play as part of pre-school learning (Hughes 2009), and there is evidence that play is crucial in developing children's 'executive functions', which are about holding information in mind, resisting distraction, inhibiting impulsive responses and switching goals (Hughes 2009:714). Hughes' (2009) study found that two items regarding family support were especially strong predictors of positive child outcomes: 'talks about fun activities at home' and 'reads regularly at home'. Although play may be an enjoyable activity, Saracho and Spodek (2006) believe that while children are playing they are engaged in reading and writing experiences which develop their literacy skills that are required for formal reading instruction.

There is evidence that reading and play have mutually enriching potential. According to a study conducted by Williamson and Silvern (1991), story re-enactment, which they refer to as thematic fantasy play, was beneficial for reading comprehension and children who engaged in more 'play talk' during play comprehended stories better than those that were less engaged. Eckler and Weininger (1991) found that children's pretend play performances may help children develop the building blocks of a story, thereby developing their early reading skills. However, although this link between learning and play is well-established, there is little research on the links between early reading and play in the South African context.

Framing learning, reading and play in theory

We use as an analytical framework Feuerstein et al.'s (Feuerstein 1979; Feuerstein, Feuerstein & Falik 2010) theory of mediated learning experience (MLE) in order to understand and analyse children's reading development in the home environment. For Feuerstein, MLE refers to 'human interactions that generate the capacity of individuals to change or modify themselves in the direction of greater adaptability and towards the use of higher mental processes' (Feuerstein 1979:110). Kozulin and Presseisen (1995:69) define MLE as 'a special quality of mediated interaction between the child and environmental stimuli' which is achieved by 'the interposition of an initiated and intentioned adult between the stimuli of the environment and the child'. Every such experience thus involves a mediator (e.g. a parent), a mediatee (e.g. a child) and an object (e.g. a book). The parent reading the book to the child mediates the child's experience of reading. For Feuerstein, 'parents are the first and intuitive mediators of the world for their children' (Feuerstein et al. 2010:xviii) and so MLE provides an appropriate lens for looking at parents' involvement in their children's reading development.

Feuerstein developed criteria that are used to understand mediated learning, namely Intentionality or Reciprocity, Transcendence and Meaning (Kozulin & Presseisen 1995). Intentionality refers to the process of deliberately directing attention towards learning (Parent to child: What do you see in the picture?). Reciprocity would be the mediatee's active responding to this intentionality ('I see a big fish and it's smiling'). In a learning situation, there are often two foci in intentionality, one being the object and the other being the child, and in such a situation the child needs to realise that the real object is not the task on hand but rather the child's own thinking (Parent: That's a good answer. You made a lovely story from that picture).

Transcendence is about identifying underlying principles, rules and values, and transmitting them to a wide range of other situations and tasks. In other words, it is about transferring and applying learning to other contexts (Child: I like going fishing with Daddy. Can Daddy catch a whale?) This is closely associated with the third criteria of meaning. Mediated learning experience can only happen when the object (stimulus, event, information) is infused with meaning by the mediator. This enables the mediatee to see the object not merely as an object (e.g. a book as unintelligible signs on a page) but as a bearer of meaning (book as story).

The mediator observes the child closely to discern what might be hindering the child's performance. The obstacle might be at any of the three phases of cognitive functioning: the child's data gathering (e.g. reading words), data processing (e.g. understanding the words) or data expression (e.g. explaining the story) (Seabi 2012). The mediator then intervenes to help the child overcome the particular obstacle.

Symbolic play

Play is associated with pleasurable activities. Aronstam and Braund (2016) characterise play as most commonly associated with children and as an active, enjoyable activity that children engage in voluntarily. Hence, play can be described as an impulsive, voluntary, gratifying and amenable activity comprising interactions of body, object and symbol use as well as relationships. According to Vygotsky (1978), play assists in a child's cognitive development and is essential for a child's success as children do not only apply their current knowledge but also acquire new knowledge through their play. He further affirms that children come to appreciate concepts by engaging in play, as play allows children to express their ideas in a natural way. Hence, children learn by watching and imitating situations around them and it is learning through trial and error that enhances a child's cognitive abilities (Mooney 2000:63).

Over the years, researchers have argued that there are different stages of play and have tried to define the characteristics or qualities of the stages of play to create a better understanding of play and the benefits it has on children. Piaget (1962) identified three stages and categories of play, namely practice play, symbolic play and games with rules. However, Smilansky (1990) has argued that Piaget (1962) has excluded a category which is crucial and that needs to be added to his categories of play, which she stated was constructive play. As cited in Wood and Attfield (2005:39), the four categories are explained:

-

Practice play is a sensori-motor and explanatory play based on physical activities.

-

Constructive play is the manipulation of objects to build or create something.

-

Symbolic play is pretend, fantasy and socio-dramatic play, involving the use of mental representations. When play becomes representational, it is regarded as an intellectual activity.

-

Games with rules is when children are expected to follow the rules of the game, such as sport.

Symbolic play has been recognised as particularly influential in children's cognitive development in that a number of intellectual skills are embedded in such play (Johnson 1976; Rubin, Fein & Vandenberg 1983). Thus, symbolic play is of particular importance as a conceptual frame in this study. As an intellectual activity, it is strongly associated with using mental representations to make meaning. Hence, 'symbolic play' can be viewed as an umbrella term which is used to refer to a range of pretend play behaviours including dress-up and role-playing as well as object substitutions (Lilliard 2001; Lewis et al. 2000; McCune-Nicolich 1981). In other words, as children play they discover that tangible objects can be represented through the use of symbols. For example, a toddler might pretend that his teddy is a phone to call 'mother', a pre-schooler might turn her muddy mixture into a chocolate ice-cream and a kindergartener might paint a picture of his family. These are all signs of emergent literacy. As children play, they are developing oral language through talking and listening, they begin to link words to their actions and as they begin to model, construct and engage in imaginative play, they extend their understanding of the meanings of words. Thus, we can deduce that symbolic play encourages literacy development by facilitating children's knowledge of how sounds and symbols work as they communicate in the play setting.

Methodology

This study was a qualitative ethnographic case study situated within an interpretivist paradigm. An ethnographer can be understood as both storyteller and scientist: 'the closer the reader of an ethnography comes to understanding the native's point of view, the better the story and the better the science' (Fetterman 1998:2). Also, an ethnographer tries to provide a detailed description about a culture or a social group. However, 'no study can capture an entire culture or group, as a result each scene exists within a multilayered and interrelated context' (Fetterman 1998:19). In this study, context, which consists of the child's environment and the settings within their environment as well as the child's social and cultural ties, played a crucial role in understanding the reading development process of each child through imaginative play.

Ethnographic case studies require the researcher to firstly create a close bond with their participants through an extended period of interaction with the participants 'as it takes considerable time to be acquainted with the participants and how they relate to the physical and material environment' (LeCompte & Schensul 1999:85). Also, building a relationship based on trust is crucial when conducting an ethnographic study. In this study, the relationships between the researcher and the participants evolved over several months from strangers to friends. This created a foundation of trust and honesty. As a result, ethnography awarded us the opportunity to gain insight and an understanding of the influence imaginative play has on Grade R learners' reading development, which created a rich and thick description of the case (Rule & John 2011:7). Secondly, ethnographic case studies are a 'step to action': they can initiate the action and add to it (Bassey 1999:23). This to us was important as there are possibilities that this study can be taken further at a later stage. Lastly, case studies as products are easier for diverse audiences to comprehend and may therefore have greater impact with a wide range of stakeholders than some other types of research (Bassey 1999).

Context of study: The setting for the study was a small town in the KwaZulu-Natal Midlands with a sizeable Indian population. Besides their broad common origins in the Indian indentured labourers (mainly Hindu) and traders (mainly Muslim) who arrived in the then British colony of Natal from the 1860s, this population is very diverse in terms of its cultural, religious and linguistic influences. While the vast majority of South African Indians (SAIs) speak English as their home language, their ancestral languages, now dying out with older generations, include Tamil, Gujarati and Hindi. South African Indians also have a range of religious affiliations, including various strands of Hinduism, Islam and many denominations of Christianity, of which most recently charismatic and evangelical have grown rapidly. Some common features of the Indian community are: English as a home language; investment in and valuing of education; strong intergenerational family set-up, which sometimes involves three or even four generations living together; strong involvement in the commercial sector and increasingly the professions; membership of the 'Indian diaspora' as the largest Indian community outside India (Desai & Vahed 2010; Hassim 2002).

The sampling in this study sought to tap into this diversity, recognising Meacham's argument regarding the importance of cultural diversity in understanding students' reading (Meacham 2001). Thus, the four purposively chosen families included one Muslim, one Christian, one Hindu family and one mixed Hindu and Muslim family. These families were sourced via a mutual friend of the researcher. The children were all in Grade R but at a variety of schools, including public and private, as well as attending religious schools (Madrassa). Using a crystallisation of sources and methods, we observed various reading episodes at each home (10 home visits per family were observed in which observations of reading development of each child were conducted with the overall home visits adding to 40 in total). In addition, we conducted semi-structured interviews with parents and handed parents questionnaires for background information. This allowed us to meet the requirements of ethnographic case studies regarding face-to-face interactions with participants. In addition, by using a variety of research methods, we were able to develop a more adequate representation of the study, and a multi-method approach has the potential of enriching and cross-validating the research findings (Gillham 2002:84).

Our first tool used in this study to collect data was questionnaires. Questionnaires are usually used to gather data from a large number of participants (Bless & Higson-Smith 2000:108). Although the sample was small in this study, a closed-ended structured questionnaire was used because we wanted to quickly and easily collect information about the parents' knowledge, belief and practices of reading because we believed this information might have an impact on their involvement in their child's reading development process. Our second method for data collection was the use of semi-structured interviews. This allowed us to gain personalised, unique and nuanced information through flexible conversations. Our third method of data collection was semi-structured observations of each child's reading development at home. Cohen, Manion and Morrison (2007) state that observations gather a lot of first-hand information and this was pertinent in our study as our observations allowed us to see what was actually happening at the participants' homes and how they developed their child's reading. Our observations were guided by several themes, namely process of reading development; methods that are used to develop reading; the involvement of parents in reading development; materials used to develop reading; and spatial and temporal arrangements when dealing with reading development. Yet, semi-structured observations allowed us to record observations which may have fallen outside of these themes, thereby enriching our data. The use of multiple methods of data collection is consistent with the ethnographic approach with its emphasis on extensive field work and multi-method triangulation (Hammersley 1990).

Data analysis consisted of thematic content analysis. Theorists (Burnard 1996; Cohen et al. 2007; Weber 1990) specify that the key feature of all thematic content analysis is that the many words of the text are classified into much smaller content categories. This method of analysis was appropriate as it helped us to refine the data into smaller categories and themes. The next step of this analytical process was to assign codes to the themes and patterns that we identified in the transcription process. These codes labelled the different themes or foci within the data (Rule & John 2011:77). They arose inductively from an analysis of the data. Although this was a time-consuming method, it allowed us to translate the data into a manageable and comprehensible form. It also had a significant impact on our findings, recommendations and conclusions, as it allowed us to get close to the data (Rule & John 2011:77). Through this process, three cross-cutting themes emerged from our analysis of the data which were reading content, reading process and social significance of reading.

The complex situation of researching families with their young children requires serious consideration of ethical issues. Cohen et al. (2007) and Rule and John (2011) believe that ethically sound research contributes to the trustworthiness of the research. Also, Rule and John (2011:112) state that 'research ethical requirements flow from three standard principles, namely: autonomy, non-maleficence (do no harm) and beneficence'. We ensured that we complied with these three standard ethical principles in our study. Informed consent was obtained from all the participating families. In addition, their anonymity was assured and their identities protected through the use of pseudonyms.

Because of the fact that our participants shared no prior relationship with us, building a trusting and ethical relationship with them was central. Hence, our relationship began with an introduction over an initial telephonic call, followed by several other general calls. This resulted in daily communications over social media which were followed by the researcher conducting a home visit to meet the family of each participant. This progressed into social outings which created greater familiarity and trust between the researchers and the participants. This resulted in an open and trusting relationship, which allowed us to visit the families at agreed-upon times without the feeling of invading their privacy.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the University of KwaZulu-Natal's College of Humanities' research ethics committee.

Findings

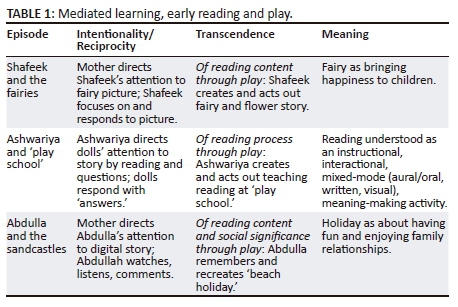

We present our findings through three short reading-play vignettes which highlight some of the links that emerged between early reading and symbolic play. These are drawn from observations of three of the families; observations of the fourth family did not add substantially to this aspect of the findings. Drawing on mediated learning theory, we discuss these vignettes in relation to children's understanding of the content, process and social significance of reading. Pseudonyms are used to protect the anonymity of participating children and families.

Shafeek and the fairies

The Ismail-Naidoo family is a mixed race (mixed race-Indian) and mixed-religion (Muslim-Hindu) family. The parents are very open about religion in their home with many books about different religions. Their son, Shafeek, attends a Waldorf school, which encourages learning through exploration and play. This vignette focuses on the co-construction of a story about fairies that came from Shafeek's 'reading' of pictures. Usually, Mr Ismail and Mrs Naidoo sat around with Shafeek while they introduced a topic that he was interested in and they began guiding each other's ideas with the end product being a remarkable story (see Box 1).

Here the pictures in the book serve as a stimulus for Shafeek's imaginative leaps. He moves from decoding the picture (fairy sitting on flower) to interpreting it ('the fairy is a good fairy … he loves the smell of flowers') and then to enacting it in his dramatic play by dressing-up and becoming the fairy. He thus makes meaning of the content of the picture by transforming it into a dramatic story ('When the fairy is happy he goes around to all the children while they are asleep and he tells them sweet stories …').

Shafeek's mother plays a crucial mediating role by prompting Shafeek with questions to develop his interpretation ('So when the fairy is happy what happens to him?'). She demonstrates intentionality by pointing him towards the next step in the narrative but without prescribing what this should be. She creates an opening for his imaginative exploration. She also encourages him and affirms his responses ('Wow! That is a really good fairy, my son, and that is a wonderful story'.) Here she is drawing attention not only to the object (the fairy story) but to the child telling the story ('good fairy', his 'wonderful story') and so to his cognitive processes of imagining, enacting and telling the story.

Ashwariya and 'play school'

The second vignette (see Box 2) is about Ashwariya Rai whose family practices Hinduism. The Rai's live as an extended family with parents, children and grandparents. The house is a reading-rich environment with book shelves, a daily newspaper, religious pictures and a family tree on the walls. Ashwariya's mother reads aloud to her as she believes this is good for Ashwariya's reading development.

Whereas Shafeek focused on the content of his story (the fairy and the flower), here Ashwariya uses dramatic play to explore the processes of reading. She takes on the role of teacher (mediator) and 'reads' aloud the story to her dolls ('mediatees'). She shows intentionality by asking questions and reciprocity by making up the dolls' answers (correct and incorrect!). Her playful exploration of the process of reading thus shows transcendence in transferring the reading experience from that of being read to (by parent or teacher) to that of reading to others in a 'school' situation. She thus learns about reading from both sides of the interaction and explores its social significance as a teaching and learning activity.

It is interesting that meaning is a powerful imperative in Ashwariya's reading-play. She expects her 'learners' to comprehend the pictures and corrects them when they do not. Also, she wishes to decode and understand the picture of the 'mouse' that she encounters in the book, and so finds out from her mother that it is a 'hamster' and communicates this to her 'learners'. For her, even though she cannot 'read', reading is a meaning-making activity and meaning matters. Her emergent literacy strongly associates reading not only with decoding signs but with constructing and co-constructing their meanings.

Captivatingly, Ashwariya reverts back to 'mediatee' when she joins her dolls to listen to her mother reading them a story. Her dramatic play shows her fascination with the processes of reading and meaning-making as a social activity invested with power relations, not least the power of interpretation ('Tinkerbell, what is in this picture? NO NO Tinkerbell!! ….. ').

Abdulla and the sandcastles

The Majid's are a Muslim family that prizes education highly. Abdulla is a 6-year-old boy who attends both Grade R and Islamic school. He is exposed to both English and Arabic, and the family reads from the Quran daily. The household is both religiously and technologically rich. His mother usually reads him stories from a tablet application (see Box 3), although she also draws books from his small book shelf. His emergent literacy thus includes the notions that reading happens in different languages, from different scripts, and using various media, and that reading can be for religious instruction and also entertainment.

In this vignette, Abdulla makes sense of the story by relating it to his own past experience and the social event of the family holiday. The story thus has social significance for him and conjures important relationships (grandmother, father) and shared activities (going to the beach, playing in the tidal pool). After the reading, he fetches his beach equipment so that he can enact the story, linked to his past experiences and his future expectations. This shows transcendence in his ability to link the story to the context of his own holiday, and meaning-making in his association of the story with fun, relationships and family time. Play may be seen here as an exploratory reworking of the meaning of the story and its social significance.

Discussion

These three vignettes cast an interesting light on the different relations between reading and play among three Grade R children. Firstly, we notice that reading in the home is a MLE in which the parent acts as mediator and imbues the object (reading material) with meaning by transforming textual signs into meaningful words which give pleasure, provoke interest, and in turn, stimulate meaning-making responses from the children in the form of play. In addition, mediated learning occurred in an environment that was understood for the child (mediatee) by the parent (mediator). The parent was actively involved in making components of that environment to suit the child as well as recognising past and present experiences of the child. This indicated that the parent was aware of and understood the child's needs, interests and capacities (Klein 2000). This was evident in Abdulla's reading event in which his mother mediated a reading experience by acknowledging her child's interest (beach) as well being aware of his past experience (family outing to the beach). In doing so, Abdulla was able to make meaning of the story through the association of his past experience.

Ashwariya, who took on the mediating role while playing, used the opportunity by directing her play experience into increasing the schemata of her recipients (dolls) in her play activity (Feuerstein et al. 2010). Also, she created a school environment (setting chairs and tables for her dolls, having a book in her hand and a ruler like a teacher) and showed signs of understanding her learners' capabilities and interests. Through 'imaginative play,' she showed intentionality with them by asking questions about the pictures in the book, and their imaginative answers highlighted reciprocity in this instance, and so her own intentionality and reciprocity in relation to the text which were played out through her imagined roles of teacher and learners, respectively. This event resonates closely with the findings in a study conducted by Eckler and Weininger (1991).

Secondly, the children's dramatic play demonstrates transcendence in the sense that they, with the mediation of their parents, transfer the reading experience to a different, remembered or invented context. While Shafeek acts out and imaginatively extends the content of the story (being a fairy), Ashwariya engages in play to explore the processes of reading (reading aloud and mediating the comprehension of others) in a different social context ('play school'). Abdulla, on the other hand, makes meaning of the story by reminiscing about a family holiday and re-enacting it in his play. This transcendence into another context assisted the young children in understanding the text and relating to the characters. Even though the emphasis in each child's play differed, the children all made meaning, by exploring the content, process and, or social significance of their reading. Hence, through the act of transcendence, the children constructed an understanding or meaning of the text.

A third feature of the reading-play relation is the spontaneity of the children's impulse to explore and express meaning. Play is a natural and pleasurable way in which they can fuse cognitive, affective, kinetic and somatic aspects as agents of meaning-making. While their parents demonstrate intentionality by scaffolding the reading process, asking questions and explaining words and pictures, the children themselves initiate their play as a way of interpreting and expressing the story. This was evident during the manifestations of play that took place in each household (Shafeek's transformation into a fairy, Ashwariya's role as a teacher and Abdulla's pretend 'beach'). These can be closely linked to Isenberg's and Jacob's (1983) understanding of symbolic play as a process in which a transformation occurs from an object or oneself into another object, person, situation or event through the use of motor and verbal actions in a make believe activity, and this provides an important source of literacy development.

Table 1 illustrates the relationship between MLE, early reading and play within each vignette. The table applies the three key concepts from MLE, that is, intentionality or reciprocity, transcendence and meaning, to the vignette.

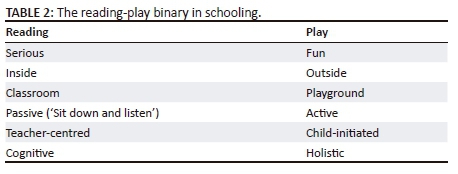

What these vignettes reveal is that play is an important meaning-making tool in these children's emergent literacy. Along with their nascent familiarity with the conventions of print and pictures, the relation between the written and the spoken, the social etiquette of listening to stories and handling reading material, the various purposes of reading, play is part of the repertoire of how they learn to understand texts and make sense of them. These insights are worth considering in a schooling context which typically separates reading from play, and so excises rich resources of children's meaning-making from the reading experience. This schooling conception of reading is based on a number of questionable binaries (Table 2) which might inhibit rather than liberate children's reading development.

We argue that teachers should consider tapping into children's meaning-making energy in the form of play as one way of developing their reading. As the vignettes suggest, play could be used to enhance and extend children's exploration of the content, process and social significance of reading, among other aspects. For example, teacher-guided play could encourage children to act out stories, invent new endings, role play characters and playfully transform the text into other media, contexts and genres. These kinds of play resonate with Hall's (1991:9) belief that children recognise the meaning of objects through exploring and experiencing them during play, but that the relationship between play and literacy is somewhat 'incidental'. In other words, Hall suggests that the relationship happens innately rather than purposely and literacy is learned when experiencing play. Hence, while teachers should preserve the intentionality of reading as a MLE, they should take care not to destroy vital elements of play: fun, creativity and initiative.

Conclusion

This article has explored the relation between early reading and play among 5-year-olds by presenting and discussing three reading-play vignettes. Drawing on the theoretical lens of Feuerstein's MLE, we argue that play is a form of transcendence through which children transfer their ideas from and about reading to other contexts. This transcendence can be enriched by adults' mediation in the form of questions, prompts and affirmative feedback. Play is a meaning-making activity that can enhance children's experience of the content, process and social significance of reading. In a schooling context that often dissociates reading and play by creating exclusionary binaries, it is worth considering how play as a natural and powerful meaning-making resource can contribute to children's reading development.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the families for participating in this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships which may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

M.N. conducted the research, wrote the thesis on which this article is based and drafted the article. P.N.R. made conceptual and interpretive contributions, developed some of the analysis and edited the article.

References

Aronstam, S. & Braund, M., 2016, 'Play in Grade R Classrooms: Diverse teacher perceptions and practices', South African Journal of Childhood Education 5(3), 6-10. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v5i3.242 [ Links ]

Barone, D., 2011, 'Welcoming families: A parent literacy project in a linguistically rich, high poverty school', Early Childhood Education 38, 377-384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-010-0424-y [ Links ]

Bassey, M., 1999, Case study research in educational settings, Open University Press, Philadelphia, PA.

Bless, C. & Higson-Smith, C., 2000, Fundamentals of social research methods, an African perspective, 3rd edn., Juta, Lansdowne, South Africa.

Burchinal, M. & Forestieri, N., 2011, 'Development of early literacy: Evidence from major U.S longitudinal studies', in S.B. Neuman & D.K. Dickinson (eds.), Handbook of early literacy research, vol. 3, The Guilford Press, New York.

Burnard, P., 1996, 'Teaching the analysis of textual data: An experiential approach', Nurse Education Today 16, 278-281. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0260-6917(96)80115-8 [ Links ]

Christie, J., Enz, B.J., Vukelich, C. & Roskos, K.A., 2014, Teaching language and literacy: Preschool through the elementary grades, 5th edn., Pearson, Boston, MA.

Cohen, L., Manion, L. & Morrison, K., 2007, Research methods in Education, 6th edn., Routledge, London.

Copple, C. & Bredekamp, S. (eds.), 2009, Developmentally appropriate practice in early childhood programmes: Serving children from birth through age eight, 3rd edn., Association for the Education of Young Children, Washington, DC, viewed 30 September 2016, from https://www.naeyc.org/store/files/store/TOC/375_0.pdf

Crawford, P.A. & Zygouris-Coe, V., 2006, 'All in the family: Connecting home and school with family literacy', Early Childhood Education Journal 33(4), 261-267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-005-0047-x [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education, 2011, National curriculum statement: Curriculum and assessment policy statement, Department of Basic Education, Pretoria.

Desai, A. & Vahed, G.H., 2010, Inside indenture: A South African story, 1860-1914, HSRC Press, Cape Town.

Eckler, J. & Weininger, O., 1991, 'Structural parallels between pretend play and narrative', Developmental Psychology 25(5), 736-743. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.25.5.736 [ Links ]

Fetterman, D.M., 1998, Ethnography: Step by step, 2nd edn., Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Feuerstein, R., 1979, The dynamic assessment of retarded performers: The learning potential assessment device, theory, instruments and techniques, University Park Press, Baltimore, MD.

Feuerstein, R., Feuerstein, R.S. & Falik, L.H., 2010, Beyond smarter: Mediated learning and the Brain's capacity for change, Teacher's College Press, New York.

Fleisch, B., 2008, Primary education in crisis: Why South African school children underachieve in reading and mathematics, Juta, Pretoria.

Gillham, B., 2002, Developing a questionnaire, Continuum, London.

Hall, N., 1991, 'Play and emergence literacy', in J. Christie (ed.), Play and early literacy development, pp. 3-25, State University of New York Press, Albany, NY.

Hammersley, M., 1990, Reading ethnographic research: A critical guide, Longman, London.

Hassim, A., 2002, The lotus people, Madiba Publishers, Durban.

Howie, S.J., van Staden, S., Tshele, M., Dowse, C. & Zimmerman, L., 2012, PIRLS 2011 summary report: South African children's reading achievement, Centre for Evaluation and Assessment, University of Pretoria, Pretoria.

Howie, S.J., Venter, E., van Staden, S., Zimmerman, L., Long, C., Scherman, V. & Archer, E., 2007, PIRLS 2006 Summary report: South African children's reading achievement, Centre for Evaluation and Assessment, University of Pretoria, Pretoria.

Hughes, F.P., 2009, Children: Play and development, Sage, UK.

Hurwitz, S.C., 2002, 'To be successful - Let them play!' Childhood Education 79, 101-102. https://doi.org/10.1080/00094056.2003.10522779 [ Links ]

Isenberg, J. & Jacob, E., 1983, 'Literacy and symbolic play: A review of the literature', Childhood Education 59(4), 272-276. [ Links ]

Johnson, J.E., 1976, 'Relations of divergent thinking and intelligence test scores with social and non-social make believe play of preschool children', Child Development 47, 1200-1203. https://doi.org/10.2307/1128465 [ Links ]

Klein, P.S., 2000, 'A mediated approach to early intervention', in A. Kozulin & Y. Rand (eds.), Experience of mediated learning: An impact of Feuerstein's theory in education and psychology, pp. 21-33, Pergamon, New York.

Kozulin, A. & Presseisen, B.Z., 1995, 'Mediated learning experience and psychological tools: Vygotsky's and Feuerstein's perspectives in a study of student learning', Educational Psychologist 30(2), 67-75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3002_3 [ Links ]

Land, S. & Lyster, E., 2011, Family literacy evaluation project 2011, viewed 30 May 2015, from http://www.familyliteracyproject.co.za/flps-2011

LeCompte, M.D. & Schensul, J.J., 1999, Designing and conducting ethnographic research, Alta Mira Press, Walnut Creek, CA.

Lewis, V., Boucher, J., Lupton, L. & Watson, S., 2000, 'Relationships between symbolic play, functional play, verbal and nonverbal ability in young children', International Journal of Communication Disorders 35, 117-127. https://doi.org/10.1080/136828200247287 [ Links ]

Lilliard, A., 2001, 'Pretend play as twin earth: A social-cognitive analysis', Developmental Review 21, 495-531. https://doi.org/10.1006/drev.2001.0532 [ Links ]

Matjila, D.S. & Pretorius, E.J., 2004, 'Bilingual and biliterate? An exploratory of Grade 8 reading skills in Setswana and English', Per Linguam 20(1), 1-21. [ Links ]

McCune-Nicolich, L., 1981, 'Toward symbolic functioning: Structure of early pretend games and potential parallels with language', Child Development 52, 785-797. https://doi.org/10.2307/1129078 [ Links ]

Meacham, S., 2001, 'Vygotsky and the blues: Re-reading cultural connections and conceptual development', Theory into Practice 40(3), 190-197. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4003_7 [ Links ]

Mooney, C., 2000, Theories of childhood: An introduction to Dewey, Montessori, Erikson, Piaget and Vygotsky, Red Leaf Press, St Paul, MN.

Piaget, J., 1962, Play, dreams, and imitation in childhood, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London.

Pretorius, E.J., 2000, 'What they can't read will hurt them: Reading academic achievement', Innovation, 21, 33-40. [ Links ]

Pretorius, E.J., 2002, 'Reading and applied linguistics - A deafening silence?', South African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies 20, 91-103. https://doi.org/10.2989/16073610209486300 [ Links ]

Pretorius, E.J. & Ribbens, R., 2005, 'Reading in a disadvantaged high school: Issues of accomplishment, assessment and accountability', South African Journal of Education 25(3), 139-147. [ Links ]

Rubin, K.H., Fein, G.G. & Vandenberg, B., 1983, 'Play', in P.H. Mussen (ed.), Hand in child psychology: Socialisation, personality, and social development, vol. 4, pp. 693-774, Wiley, New York.

Rule, P. & John, V., 2011, Your guide to case study research, Van Schaik, Pretoria.

Rule, P. & Land, S., 2017, 'Finding the plot in South African reading education', Reading & Writing 8(1), a121. https://doi.org/10.4102/rw.v8i1.121 [ Links ]

SACMEQ, 2002, SACMEQ Project 11 2000-2002, UNESCO, Cape Town.

SACMEQ, 2007, SACMEQ Project 111, UNESCO, Cape Town.

Saracho, O.N. & Spodek, B., 2006, Handbook of research on the education of young children, 2nd edn., Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, NJ.

Seabi, J., 2012, 'Feuerstein's mediated learning experience as a vehicle for enhancing cognitive functioning of remedial school learners in South Africa', Australian Journal of Educational & Developmental Psychology 12, 35-45. [ Links ]

Smilansky, S., 1990, 'Sociodramatic play: Its relevance to behaviour and achievement in school', in E. Klugman & S. Smilasky (eds.), Children's play and learning: Perspectives and policy implications, pp. 18-42, Teachers College Press, New York.

Sporer, N., Brustein, J.C. & Kieschke, U., 2009, 'Improving students' reading comprehension skills: Effects of strategy instruction and reciprocal teaching', Learning and Instruction 19(3), 272-286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2008.05.003 [ Links ]

Tsoa, Y.L., 2008, 'Using guided play to enhance children's conversation, creativity and competence in literacy', Education 128(3), 515-520. [ Links ]

Vygotsky, L.S., 1978, Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Weber, R.P., 1990, Basic content analysis, Sage Publications, Newbury Park, CA.

Williamson, P.A. & Silvern, S.B., 1991, 'Thematic-fantasy play and story comprehension', in J. Christie (ed.), Play and early literacy development, pp. 69-90, State University of New York Press, Albany, NY.

Wood, E., 2009, 'Conceptualising a pedagogy of play: International perspectives from theory, policy and practice', in D. Kuschner (ed.), From children to Red Hatters: Diverse images and issues of play, pp. 166-189, University Press of America, Lanham, ML.

Wood, E. & Attfield, J., 2005, Play, learning and the early childhood curriculum, Paul Chapman, London.

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Peter Rule

prule2015@sun.ac.za

Received: 15 Dec. 2016

Accepted: 15 Apr. 2018

Published: 27 June 2018