Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Childhood Education

On-line version ISSN 2223-7682

Print version ISSN 2223-7674

SAJCE vol.8 n.1 Johannesburg 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v8i1.477

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Arts across the curriculum as a pedagogic ally for primary school teachers

Eurika N. Jansen van VuurenI, II

IDepartment of Childhood Education, University of Johannesburg, South Africa

IIDepartment of Childhood Education, University of Mpumalanga, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The arts as a pedagogic medium can be an important tool for language learning, and yet many teachers avoid it, often because of a lack of confidence. The main purpose of this study was to explore the possibility of generalist educators, as opposed to art specialists, using the arts successfully as a cross-curricular tool to accelerate English First Additional Language acquisition. Most South African learners speak African languages as a mother tongue, yet they are taught in English from Grade 4 onwards. With the use of an action research project, learners' English proficiency was assessed with a custom-designed tool and, thereafter, they participated in 10 weekly sessions of arts-integrated English activities before being re-assessed. Positive results confirmed that generalist educators are able to utilise arts, and it showed the urgency for more focused arts-integrated educational training in generalist educator courses at South African universities. Although the research was limited in scope, it raises the question of how teachers for the primary school are educated with regard to learning a language with the use of the arts.

Introduction

The current situation in South African schools

In rural South Africa, many learners lack English skills as it is not the vernacular, and exposure to English of a suitable quality that will assist learners to progress optimally in school is limited. This situation is exacerbated when parents with skills migrate to urban areas to find employment and leave their children in the care of unemployed and sometimes illiterate relatives (Nores and Barnett 2010:272). Unfortunately, many of these households in which the children are left are poor and these children most often do not reach literacy and numeracy milestones. 'Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest prevalence of children at risk of not reaching developmental potential' (Black et al. 2017:77). The learners in these rural schools not only lack literacy and numeracy skills but also experience challenges with fine motor skills, like cutting with a scissor or even tying their shoelaces. When these learners start school, they also have extremely limited English skills. They need to be supported to acquire English skills rapidly because English serves as the language of learning and teaching (LoLT) from Grade 4 onwards.

The teachers

Sadly, the teachers in many of the rural schools do not have the necessary English language skills to prepare learners for the transition from mother tongue teaching and learning to English as LoLT in Grade 4. To conceal their limited English skills, teachers sometimes use code-switching as a way of coping.

The author would argue that, to assist generalist teachers in their endeavour of teaching English, integrating the arts (dance, drama, music and visual arts) can be an invaluable pedagogic ally. In this study, she specifically refers to generalist teachers since South African public primary schools rarely have specialists who can teach the arts and must, therefore, rely on the class teacher to teach the art components (Russell-Bowie 2010). The proper skills needed to be able to use arts-integrated teaching methods are lacking in the education sector in general. Educators often have limited art skills because of their own education having been compromised by insufficiently-trained arts educators (LaJevic 2013:3). If pre-service and in-service training does not address the shortfall, the situation is repeated when educators do not have the skills to enrich their own learners through the arts. If generalist educators can be empowered to use the arts confidently in class, it can assist not only with learners' acquisition of art skills but also be invaluable in general subjects, improving the serious English language deficiencies in the schooling system (Appel 2006; Department of Basic Education 2014).

When exploring the literature, it is clear that using arts as teaching support in an educational setting is not novel (Hallam 2010; Lowe 2002; Paquette & Rieg 2008). The challenge is to train and motivate generalist educators to use arts-integrated teaching without compromising the integrity of the arts. Much is said about the plight of generalist educators having to teach all the arts (Jeanneret & DeGraffenreid 2012), yet adaptations to curricula and practical ideas are not forthcoming. Many educators do not have the confidence to use the arts because of their never having had the practical experience. LaJevic (2013:3) maintains that 'Arts Integration [is] a scary place for teachers' because they were not exposed to it in their own schooling.

Defining arts-integrated teaching

When referring to arts-integrated teaching, there are varying definitions. To delineate an appropriate definition, Russell-Bowie's (2009:5) three models of arts-integrated teaching must first be considered, namely, service connections, symmetric correlations and syntegration. The service connection model refers to a situation where a subject is taught and an activity from another subject is used to assist with retention, for example, teaching about the history of ships and then singing a song like 'Michael row the boat' to learn about elements of ships. In this case, no music concepts are taught.

Symmetric correlations is a model in which there is equal emphasis on both subjects, for example, the history of ships is taught and the song 'Michael row the boat' is used as a song to teach learners about rowing and trimming the sails. In this instance, different aspects of music would be included and the song would not only be used for its lyric content but also for teaching elements of music. The teacher could discuss the type of song and then teach the use of dynamic differences and their terminology.

Syntegration is a combination of the words 'synergy' and 'integration', and it implies that better outcomes are achieved when the subjects work together than when they work alone.

In this study, the author uses the symmetric correlations model in her definition of arts-integrated teaching. She defines it as a teaching strategy in which the arts are integrated into another subject as a meaningful component, and not merely as a decorative or time-filling activity in which learners draw a picture or sing a song.

Why use arts integration?

Many authors concur that arts integration is important in primary school as a way to enhance teaching and learning, and even more so if there are no arts specialists in the school (Appel 2006) to assist in developing the creativity that goes along with art skills. According to Dewey (1986) and Gardner (1993), the use of an integrated curriculum provides learners with multiple access points because it takes into consideration a range of learning styles and intelligences. Chapman (2015) adds a myriad of benefits to integrated arts teaching by mentioning, among others, the development of deep and unique ways of knowing, respect for other cultures and enhanced socio-emotional development, and creativity. The author agrees with Loepp (1999:2) that real-world problems are not limited to one discipline - a multidisciplinary approach is needed to solve these problems.

Teacher training

The arts are underutilised worldwide and existing research mentions several reasons for this, including lack of sufficient pre-service (Collins 2014; Chapman 2015; Russell-Bowie 2010) and in-service training (Power & Klopper 2011). Failoni (1993) refers to the importance of pre-service training to ensure that the arts are meaningfully integrated and not relegated to entertainment status. The intrinsic value of the arts forms must be retained through the incorporation of art principles and elements. Furthermore, LaJevic (2013:2) adds another facet to the value of arts-integrated teaching by arguing that we need to move away from static arts teaching and learning to not only connect the arts to other academic subjects, but also to explore the arts 'as a way to make meaning of learners'/teachers' lives and the world in general.'

South African universities generally have single-semester modules that cover all aspects of the four basic arts forms, but it is not possible to learn and master a new skill in such a short time (Van Vuuren & van Niekerk 2015). Russell-Bowie (2012) agrees and states that:

teacher educators need to reflect carefully on how they can address these challenges and increase the confidence and competence of their generalist pre-service primary teachers through innovative approaches despite the decrease in face-to-face hours. (p. 62)

In addition, Vermeulen, Klopper and van Niekerk (2011:201) are concerned that 'most higher education institutes provide an overview of the various arts forms without focusing on the development of knowledge and specific skills in each discrete arts form'. The lack of depth in arts knowledge is a contributing factor to educators avoiding the arts in the classroom. When teachers have not acquired practical skills in the arts (in addition to theoretical knowledge), they will not use them effectively in the classroom.

How is language learnt?

As a framework for this research, the author used the music philosophy of Suzuki Talent Education Association of Australia (Victoria) (n.d.), who asserted that mother tongue learning occurs through a process of listening, imitation and repetition. He consequently based his method of music tuition on the premise that music and language skills are acquired in a similar way. Utilising this resemblance between music and language learning to complement second language acquisition makes sense in the music-rooted African context.

To complement Suzuki's ideas, the author used elements of the English First Additional Language (EFAL) research of Konishi et al. (2014:414), which provides six principles of language learning. These principles, which harmonise with the use of the arts, are as follows: learners must hear more English (through singing songs, doing drama and reading), learning materials must capture the interests of learners (most children enjoy arts activities), learning environments must be interactive and fun (the arts are often interactive and meet the criterion of fun), learners must hear different accents by different English speakers (which can be met through listening to different recorded versions of songs or the accent of the teacher), vocabulary and grammar must play a complementary role in language learning (vocabulary and grammar is included in the complementary mode as the arts activity is usually the focus) and learning must occur within a meaningful context (correctly chosen songs, explorative visual arts activities and drama provide meaningful contexts).

Aims and objectives

The main aim of this study is to gauge the possible impact of arts-integrated teaching in the EFAL classroom setting through the use of simple art activities. The research objectives are, first, to explore art activities as support for English language acquisition and, second, to ascertain the skills needed by generalist educators to implement the arts-integrated teaching style effectively. Furthermore, general arts activities are suggested that support the South African curriculum topics and that can be used confidently in arts-integrated teaching by generalist educators. The knowledge gained could assist universities and education departments to reconsider and streamline arts curricula for generalist educators.

Research methods and design

The pragmatic paradigm described by Mackenzie and Knipe (2006:4) as having aspects of mixed models and which looks at the consequences of actions is perfectly suited to the research as it is 'real-world practice orientated'. The author explored 'consequences of actions' by initiating an arts-integrated language programme and studying its outcomes through a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods.

Data were collected during the author's involvement as subject advisor in a project initiated by the Zululand Education District during 2013. Subject advisors were encouraged to start educational projects of their choice in the district. The author chose to assist a class in a rural school with English skills through the use of traditional English children's songs and other complementary arts activities that integrate well with the curriculum.

Permission to use the observations and data for research purposes was obtained from the Chief Education Specialist for Curriculum in the Zululand Education District. All educators involved in informal interviews signed forms of consent.

The unit of research was not preselected. The class that was made available to the author was a Grade 4 class with only 10 learners, making it possible to develop a trust relationship despite the culture and language differences. The author is a white person and from the Afrikaans culture, whereas the learners were predominantly African and isiZulu speakers. According to the class educator, the majority of the learners live in informal settlements with relatives who are often early school leavers and speak English with difficulty. These learners were fairly representative of the majority of learners in the rural areas of KwaZulu-Natal, where 42% of learners are orphaned - having lost either one or both parents (Anderson & Phillips 2006).

For the author's intervention, she chose 10 songs that link to topics in the National Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) regarding EFAL, Life Skills and Natural Sciences, and built a programme around these. The author only spoke English and did not resort to continuous code-switching (between isiZulu and English) like many educators (Jantjies & Joy 2015) in the current South African education system. It is important to note that the learners in rural areas, who are in Grade 4, have very little language skills and the programme was developed keeping their English ability in mind.

CAPS topics that were included from the Grade 4 curriculum included the following:

EFAL: Listening and Speaking, Reading and Viewing, Writing and Presenting, Language Structures and Conventions.

Life Skills: Social Responsibility, Development of the Self, Performing Arts (warm-up and play; improvise and create; read, interpret and perform; and appreciate and reflect) and Visual Arts (visual literacy; create in two dimensions [2D] and three dimensions [3D]; and elements and principles).

Natural Science and Technology: Life and Living, Planet Earth and Beyond.

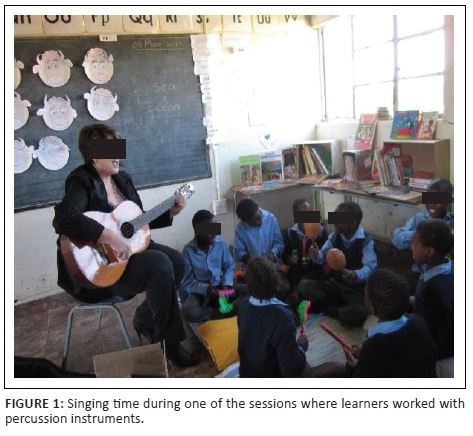

Learners were presented with a book into which traditional English children's songs were pasted, complemented with a worksheet and/or instructions for an art activity. A word wall was created and new words that occur in the songs were added during each session. The word wall consisted of an alphabet frieze, and learners were invited to take turns to add the newly-learnt words (on flash cards) to it. A variety of instruments, mainly percussion, were incorporated into most of the sessions, which consisted of the following: djembe, one guitar, maracas, claves, tambourines and homemade rattles and shakers. Easily obtainable, cheap materials were used for art activities to add to the learning experience and to demonstrate that expensive resources are not required. The envisaged programme (Table 1) was discussed with all educators at the school, and they were invited to observe the sessions if they were able. On the last day of the programme, educators were interviewed informally. Table 1 presents an outline of the contents covered in each session.

A test, used as both pre- and post-test, was set using a format similar to that used by the South African Department of Basic Education during the Annual National Assessment (Appendix 1). Only three of the words that are in the song lyrics were included in the test.

Teaching sessions

The first session started with mutual introductions and activities like the creation of a word wall and an explanation of the concept of a word wall to the learners. They were taught the names of the instruments and how to play them. Each learner had the opportunity to play their name rhythm and the rhythm of the instruments' names using a percussion instrument. At this stage of the lesson, learners were merely improvising with the instruments and playing in unison. Instrument names were added to the word wall. The author sang a song ('Lord of the Dance') using a guitar as accompaniment, and learners were invited to join in during the simple repetitive chorus, using their percussion instruments (Figure 1). Learners then read the lyrics of the song with the author and were assisted with linking the content of the song to a religion. A selection of difficult words from the song were explained and added to the word wall. Christianity as religion was briefly discussed. After repeating the song chorus in several different ways using dynamics and tempo variations, learners proceeded to complete a baseline assessment test to determine their English proficiency. The mother tongue isiZulu-speaking class teacher explained to them in isiZulu that the purpose of the test was to see how they could be assisted and that it was not going to make them pass or fail. They were not assisted with any of the questions. To end the session, 'Lord of the Dance' was sung several times with percussion accompaniment variations.

All sessions shared a similar format: greeting, singing previously learnt songs and a quiz about previously-learnt vocabulary. After the revision, a new song was learnt and repeated several times with a focus on linking subject content, art elements and principles as well as vocabulary. To assist with vocabulary, pictures were sometimes used as additional resources. A variety of percussion instruments were used in different combinations as song accompaniment. New vocabulary was added to the word wall and then followed by an art activity and/or completion of a worksheet. At the end of each session, the new song was repeated. Some educators often came in to join the lessons.

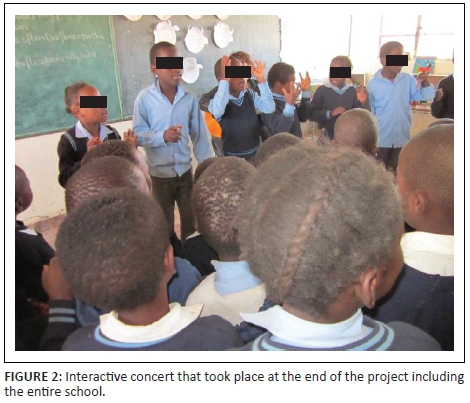

During the final session, the Grade 4 class rewrote the baseline test and presented an interactive concert (Figure 2), among other activities.

Results

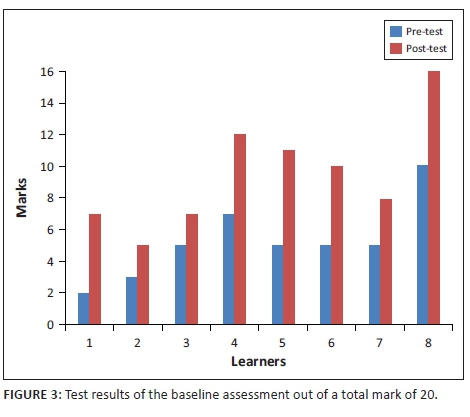

Quantitative results were obtained from the test results and qualitative results from interviews, observations and video clips. As only eight learners were present on the day of the test, only eight tests could be compared (Figure 3).

The pre-test showed an average mark of 26.25% and the post-test had a 47.5% average - equating to an average improvement of 21.25%. Three of the test questions covered vocabulary that was contained in the songs, and these answers showed a 45.8% average improvement. A question in which a calculation needed to be done showed no improvement.

There was a marked increase in the confidence of the learners during communication with the author (in English), as can be seen in videotaped snippets of the sessions. The class educator reported that the general interest in English communication had risen and that learners frequently asked whether they could sing the songs they had learnt. Learners were very proud of their displayed artwork that they had completed during the sessions.

Interviews held with generalist educators after the programme suggested that they would be able to implement the programme and cope with the activities but they had never 'thought' of doing it together in such a way. Some educators were worried that they could not play a guitar and that this might deduct from the novelty of singing with instrumental accompaniment. The general view, however, was that it would not matter. Two of the educators mentioned that they would need to be assisted with new ideas and songs. An educator from an adjacent class noticed that some learners were often practising to read the new vocabulary on the word wall by pointing to it with the educator's stick when they were left alone in class. The children's activity shows that the word wall has an important role in the classroom.

Discussion

The key findings are that arts activities have a positive impact on second language acquisition as was noticeable in the test results that showed a general improvement in the answering and understanding of the questions as well as vocabulary. The more pronounced improvement in the test questions that contained song vocabulary can be seen as possible evidence that the improvement is even more enhanced when specific vocabulary is targeted in songs.

Despite the absenteeism of some learners during some sessions, everybody showed an improvement in marks, which confirms that arts-integrated teaching can have a positive effect on the development of language skills. This teaching method created a relaxed and creative atmosphere conducive to learning, and generalist educators indicated that they would be able to replicate it.

Although it is evident that music and song in particular, and arts in general, have an influence on the acquisition of an additional language, it was difficult to measure the precise influence because of a variety of factors:

-

It was the second time that these learners wrote the exact same test, which could have assisted them in understanding the structure of the questions better. Two similar tests should be used rather than one test.

-

The learner improvement could be partially because of the teaching method.

-

The author only spoke English to the learners during the sessions as opposed to the code-switching to which they are accustomed.

It would be interesting to duplicate the study in a more affluent area to see whether the results correspond.

Conclusion

In South Africa, where there is a need for interventions to master English in schools, the use of arts-integrated teaching makes sense. Universities need to ensure that generalist educators do not only have theoretical arts knowledge but also have the opportunity to develop practical skills so that they can use integrated arts teaching confidently in the classroom. Using the arts does not require vast financial resources - a voice, homemade percussion instruments, cardboard, glue, crayons and scissors will suffice. By training pre-service and in-service generalist educators sufficiently in arts integration, the EFAL deficiency in South African schools can be markedly improved.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships which may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

References

Anderson, B.A. & Phillips, H.E., 2006, Trends in the percentage of children who are orphaned in South Africa: 1995-2005 (03-09-06), Statistics SA, Pretoria, viewed 04 April 2016, from http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/Report-03-09-06/Report-03-09-062000,2005.pdf

Appel, M.P., 2006, 'Arts integration across the curriculum', Leadership 36(2), 14-17. [ Links ]

Black, M.M., Walker, S.P., Fernald, L.C., Andersen, C.T., DiGirolamo, A.M., Lu, C. et al., 2017, 'Early childhood development coming of age: Science through the life course', The Lancet 389(10064), 77-90. [ Links ]

Chapman, S.N., 2015, 'Arts immersion: Using the arts as a language across the primary school curriculum', Australian Journal of Teacher Education 40(9), 86-101. [ Links ]

Collins, A., 2014, 'Neuroscience, music education and the pre-service primary (elementary) generalist teacher', International Journal of Education and the Arts 15(5), 1-20. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education, 2014, Report on the Annual National Assessment of 2014: Grades 1-6 & 9, Department of Basic Education, Pretoria.

Dewey, J., 1986, 'Experience and education', The Educational Forum 50(3), 241-252. [ Links ]

Failoni, J.W., 1993, 'Music as means to enhance cultural awareness and literacy in the foreign language classroom', Mid-Atlantic Journal of Foreign Language Pedagogy 1, 97-108. [ Links ]

Gardner, H., 1993, Multiple intelligences: The theory in practice, Basic Books, New York. [ Links ]

Hallam, S., 2010, 'The power of music: Its impact on the intellectual, social and personal development of learners and young people', International Journal of Music Education 28, 269-289. [ Links ]

Jantjies, M. & Joy, M., 2015, 'Mobile enhanced learning in a South African context', Journal of Educational Technology & Society 18(1), 308-320. [ Links ]

Jeanneret, N.E.R.Y.L. & DeGraffenreid, G.M., 2012, 'Music education in the generalist classroom', The Oxford Handbook of Music Education 1, 399-416. [ Links ]

Konishi, H., Kanero, J., Freeman, M. R., Golinkoff, R. M. & Hirsh-Pasek, K., 2014, 'Six principles of language development: Implications for second language learners', Developmental Neuropsychology 39(5), 404-420. [ Links ]

LaJevic, L., 2013, 'Arts integration: What is really happening in the elementary classroom?', Journal for Learning through the Arts 9(1), 1-28. [ Links ]

Loepp, F.L., 1999. 'Models of curriculum integration', The Journal of Technology Studies 25(2), 21-25. [ Links ]

Lowe, A., 2002, 'Power of the integration of the arts in the language classroom', Journal of Border Educational Research 3(2), 1-9. [ Links ]

Mackenzie, N. & Knipe, S., 2006, 'Research dilemmas: Paradigms, methods and methodology', Issues in Educational Research 16(2), 193-205. [ Links ]

Nores, M. & Barnett, W.S., 2010. 'Benefits of early childhood interventions across the world: (Under) Investing in the very young', Economics of Education Review 29(2), 271-282. [ Links ]

Paquette, K.R. & Rieg, S.A., 2008, 'Using music to support the literacy development of young English language learners', Early Childhood Education Journal 36(3), 227-232. [ Links ]

Power, B. & Klopper, C., 2011, 'The classroom practice of creative arts education in NSW primary schools: A descriptive account', International Journal of Education & the Arts 12(11), 1-26. [ Links ]

Russell-Bowie, D., 2009, 'Syntegration or disintegration? Models of integrating the arts across the primary curriculum', International Journal of Education & the Arts 10(28), 1-23. [ Links ]

Russell-Bowie, D., 2010, 'Cross-national comparisons of background and confidence in visual arts and music education of pre-service primary teachers', Australian Journal of Teacher Education 35(4), 65-78. [ Links ]

Russell-Bowie, D.E., 2012, 'Developing pre-service primary teachers' confidence and competence in arts education using principles of authentic learning', Australian Journal of Teacher Education 37(1), 60-74. [ Links ]

Suzuki Talent Education Association of Australia (Victoria) 'What is the Suzuki Method?', n.d., viewed 06 February 2016, from http://www.suzukimusic.org.au/suzuki.htm

Van Vuuren, E.J. & Van Niekerk, C., 2015, 'Music in the Life Skills classroom', British Journal of Music Education 32(3), 273-289. [ Links ]

Vermeulen, D., Klopper, C. & Van Niekerk, C., 2011, 'South-south comparisons: A syntegrated approach to the teaching of the arts for primary school teacher preparation in South Africa and Australia', Arts Education Policy Review 112(4), 199-205. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Eurika Jansen van Vuuren

eurika.jvvuuren@ump.ac.za

Received: 11 Jul. 2016

Accepted: 13 Jan. 2018

Published: 28 Mar. 2018

Note: The research of this article is based on a master’s thesis previously published by the author.

Appendix 1: The test (pre-and post-test) used during the action research project

Baseline assessment: Grade 4 Second Language Project

Name:_______________________________________

Read the text below and then answer the questions:

Cindy is a girl of 10 years old. She lives near Vryheid with her grandmother and two little brothers: Sipho who is 4 years old and Elias who is 8 years old. Their home is very small but it is tidy and clean. All the children help their granny to clean the house.

They are a very happy family and spend a lot of time planting and caring for the vegetables in their garden. They have planted mealies, potatoes and pumpkins and always have fresh vegetables to eat.

Sipho is still very young and does not go to school. When Cindy and Elias come back from school in the afternoon, they read stories to Sipho because they want him to be clever. Their teachers told them that children get very clever if they read many books. Sipho's favourite stories are the ones about animals.

Choose the correct answer and circle the letter next to it.

Question 1

Cindy is the youngest child in her family.

a) Yes

b) No

c) Unsure (1)

d) Sometimes

Question 2

Granny sells vegetables to the neighbours.

a) Yes

b) No

c) Unsure (1)

d) Sometimes

Question 3

Sipho likes stories about animals.

a) Yes

b) No

c) Unsure (1)

d) Sometimes

Question 4

Elias is _______ years older than Sipho.

a) 2

b) 3

c) 4 (1)

d) 5

Question 5

Sipho is in Grade 1.

a) True

b) False (1)

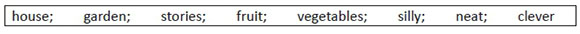

Complete the sentences below by choosing a word from the box:

Question 6

Elias and Cindy often read _____________ to their little brother. (1)

Question 7

Mealies and potatoes are ______________. (1)

Question 8

Children who read a lot get very _______________. (1)

Question 9

This family spends a lot of time in the _______________. (1)

Question 10

The children's home is very _________________. (1)

Study the school timetable below and then answer the questions:

Question 11

What do the children do after 14:00 every day? (1)

_______________________________________________________________________

Question 12

At what time during the school day do the children go out to play? (1)

_______________________________________________

Question 13

What do the children do in Lesson 4 on Thursday? (1)

_______________________________________________

Question 14

Name the two days that come after Friday. (2)

_________________

_________________

Question 15

Study the pictures below and then write which body part is injured using correct English. (3)

Question 16

Write a sentence where you tell us which subject is your favourite. Give a reason. (2)

_______________________________________________________________________

TOTAL: 20