Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Childhood Education

On-line version ISSN 2223-7682

Print version ISSN 2223-7674

SAJCE vol.6 n.1 Johannesburg 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v6i1.406

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Interrogating quality in early childhood development: Working towards a South African perspective

Lorayne Excell

Foundation Studies, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Within the South African context, early childhood development (ECD) is receiving increasing attention at both government and civil society levels. This has resulted in children accessing ECD services in increasing numbers. But although access may open the doors to learning, it does not ensure a quality early learning experience for children. The pivotal factor is quality. Quality ECD has the potential to drive redress and realise the promise inherent in the South African Constitution. The study draws on the three dimensions of a community of practice, to explore how new dialogic spaces are emerging, spaces that have the potential to generate innovation, reflection and new understandings of what could constitute quality ECD throughout South Africa. Using an action research design, this study will trace how understandings of what constitutes quality ECD in South Africa have already begun to be interrogated by a number of different stakeholders.

Introduction

We live in an age where quality has become the buzz word. Every product and service must offer quality; every consumer wants to have it (Dahlberg, Moss & Pence 2013). Early childhood development (ECD) is no exception. For example, the word quality is mentioned over 200 times in relation to ECD service delivery, teaching and learning in the draft Early Childhood Development Policy Document (Department of Social Development [DSD] 2015). But nowhere in this document is an attempt made to qualify what is intended or understood by this word.

This uncritical blanket acceptance of the word supports the argument by Dahlberg, Moss and Pence (2007), Dahlberg et al. 2013) that quality has become reified. It treated as if it is an essential attribute of services or products that gives them value, assumed to be natural and neutral. But, as Dahlberg et al. (2007, 2013) point out, quality is not a neutral concept. Neither are understandings of what constitute quality uncontested. It is a complex and multifaceted concept with interpretations predominately drawn from western perspectives (Dahlberg et al. 2013). However, these perspectives, might not be germane to the current, disparate ECD contexts found in South Africa.

Despite these contested views of what constitutes quality, it is widely accepted that if ECD input is to have any lasting positive impact on children's development and learning, quality (whatever it might mean) is key to improving the health, as well as the cognitive and socio-emotional development of young children (Administration for Children and Families 2002; La Paro, Pianta & Stuhlman 2004; Pausell, BollerHallgren & Mraz-Esposito 2010 ). Yet, according to Britto, Yoshikawa and Boller (2011), we lack understanding of how to measure the quality of early learning environments, especially in low- and middle-income countries, and how to apply the results to improve ECD practice and policy. The task of conceptualising, measuring and improving quality is important because, along with access, quality is a key feature of successful policies. Together, access and quality enable policies to contribute to the goal of equity in ECD (Britto et al. 2011).

Internationally, there appear to be some generally accepted indicators (to be outlined later in the text) of what could constitute quality in ECD. Therefore, the author argues that if there is not some common understanding of quality within disparate South African contexts, child outcomes in relation to development and learning will continue to be compromised. A relevant question thus becomes what constitutes quality from a South African ECD perspective?

This study is part of an ongoing project that attempts to answer this question. The aim is not to seek a definitive answer but rather to describe a collaborative process of how ECD stakeholders came to some initial common understandings of what could constitute quality in different ECD settings. The study first interrogates the contested nature of quality and explores an alternative lens through which different understandings of quality could be interrogated. It then examines, using an action research model, how through a participatory, interactive process, a fledgling ECD community of practice (CoP) negotiated different understandings of the concept of quality with the ultimate aim of developing a conceptual framework that would be informed by these shared understandings. Finally, the study outlines the draft conceptual framework of shared understandings of quality in ECD and explores a way forward for the ECD CoP.

An understanding of quality in early childhood development

As already mentioned, quality is key to effective ECD service delivery, but as a dynamic, flexible and adaptable construct, it is difficult to pin down. According to Moss and Pence (1994):

quality in early childhood services is a constructed concept, subjective in nature and based on values, beliefs and interest, rather than an objective and universal reality. (p. 172)

Dahlberg et al. (2013) claim that contemporary conversations about quality have come to acknowledge diversity and the notion of 'both/and' rather than the more dualistic 'either/or' approach. This open-ended approach allows for the possibilities of multiple understandings of the concept in varying teaching and learning contexts. As Britto et al. (2011) comment 'quality contours itself across cultures, settings, time and types of intervention' strengthening Peralta's (2008) observation that real quality improvement happens when there is a shared understanding and agreement by stakeholders of what quality is and how it can be achieved.

But the term 'quality' also suggests uniform standards (Britto et al. 2011). This understanding of quality is easy to accept as in many policy documents the notion of uniform standards is reinforced. As Alexander (2009), writing from an English perspective comments, various contradictory policy documents guide practice and set out a developmental framework and a series of learning goals that all children should attain before commencing school. These learning goals frequently drive ECD practice. The author suggests that the situation is no different in South Africa where on the one hand policy documents suggest a quality practice based on children's play interests but on the other hand curriculum and other guidelines establish relatively fixed learning goals (see, e.g. the Curriculum Assessment Policy Statement [Department of Basic Education - DBE 2011; the National Curriculum Statement [DBE 2015]; National Early Learning Development Standards [DBE 2009]). Within these frameworks, the flexible and dynamic aspects of quality can be easily disregarded in favour of a more prescriptive approach to teaching and learning.

Although the author has previously argued that the construct is multifaceted and resists a simple definition, there are nonetheless some overall elements of childcare that are identified as critical to the well-being of children. Paramount is ensuring the well-being of children through adequate health and safety practices, which include good hygiene and nutrition. In addition, a well-maintained and resourced environment appropriate for children is crucial. Sammons et al. (2007) note that staff receptiveness is important and is dependent upon an adequate number of appropriately qualified staff who are sensitive and responsive to children. Staff, who guide children's learning by providing opportunities for active as well as quiet play and rest, join children in their play and ask open-ended questions that promote sustained shared thinking are essential to high-quality teaching and learning (Sammons et al. 2007). Such practices also provide opportunities for developing motor, social, language and cognitive skills through play, support and positive interaction among children and facilitate emotional growth and well-being. Furthermore, support for communication with parents as well as respect for diversity and difference, social justice, gender equality and inclusion of children with disabilities are essential indicators of quality.

Proponents of high-quality childcare thus advocate broad learning and development outcomes for children. These go beyond narrow academic aims limited to early literacy and numeracy. Social, emotional, cultural, creative and physical outcomes are also emphasised. The approach is one that 'allows children to be children' and one that promotes experiential learning through play (Irwin, Siddiqi & Hertzman 2007; National Forum on Early Childhood Program Evaluation 2007; Peralta 2008).

Yet, despite overwhelming agreement that these are the essential elements of quality in ECD, Siraj-Blatchford and Woodhead (2009) maintain that in both developed and developing countries the average level of quality in ECD is not high enough to ensure that all children reap the benefits of early childhood education. One possible reason is that these elements do not take cognisance of the broader ECD field and its complexities. They become uniformly interpreted negating aspects related to contexts and cultural appropriateness. Peralta (2008) argues that this is one of the challenges within current ECD service delivery in South Africa.

ECD delivery is indeed challenging. The sector's players and target population vary enormously making it extremely difficult to conceptualise what quality would look like in different ECD settings and contexts. There are a wide range of ECD programmes and settings, varying from mere places of care for infants and children to preschools offering comprehensive early education and care services. In addition, there are parenting and home visiting programmes as well as early stimulation, nutrition interventions and other related healthcare programmes.

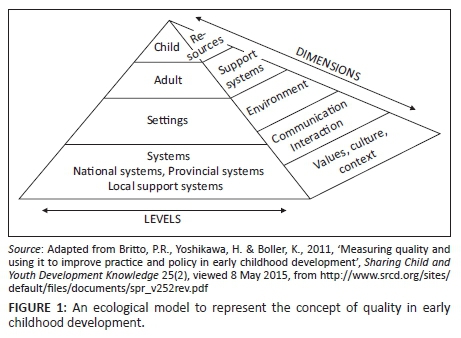

Thus, a broader conceptual framework outlining common understandings of quality ECD education and care could possibly prevent some of the current narrow static interpretations and promote an increased in-depth understanding of what comprises quality in ECD. In an attempt to broaden this understanding of quality, Britto et al. (2011) have developed an ecological pyramid model that argues for a more complex conceptualisation of quality and provides an alternative lens for in-depth interrogation of this concept in disparate and complex ECD settings and could provide a lens through which, within the South African context, quality in ECD could be interrogated.

Unpacking the levels and dimensions of quality

The model is based on four different levels and five dimensions, which cut across these four levels (see Figure 1).

Levels of quality

The first level of the pyramid, starting from the top down, considers the children and their well-being. Children's well-being is usually measured by the characteristics shown by carers demonstrated through their interactions with children. Well-being (physical, emotional and social), cognitive stimulation, language and managing behaviours typically form part of these interactions.

The second level targets the adults (parents, practitioners, childcare providers, health and other service providers) who are responsible for the care and education of children. Again, according to Britto et al. (2011), quality can be measured through observing the characteristics of the adult and how these might influence children's health, development and learning.

The third tier is that of settings. These are conceived broadly and include a variety of centre- as well as home-based and other communal settings; in fact, any space where childcare services are offered. Quality assessment measures include adult-staff ratios, qualifications of caregivers, quality of interactions with children and other stakeholders.

The base of the pyramid comprises the larger organisational and institutional structures within which ECD services are situated and managed. These structures are referred to as systems and three sublevels outlined in Figure 1 are identified. These are local support systems, subnational (provincial) systems and national systems. These systems align well with existing governing structures found in South Africa and which provide similar functions to those outlined by Britto et al. (2011).

Functions of the local support systems might be delivered by non-governmental organisations (NGOs), private providers or local government and include ways of providing resources to local programmes, training provisioning and places of local service delivery such as health centres. In this model, subnational systems could be viewed as a provincial competence responsible for administering the local support systems and coordinating policy. They could be private, public or a combination. The third sublevel is the national system comprising various government departments, international NGOs and foreign-based support. Though Britto et al. (2011) recognise that it is essential to assess quality at all four levels, they note that it is more challenging to assess quality at a systems level. Consequently, the quality of these support systems is frequently overlooked when conceptualising ECD.

Dimensions of quality

The dimensions, which cut across each of the four levels, provide opportunities to consider what constitutes quality in fundamentally different contexts. The five dimensions are:

1. Alignment with the values and principles of a community or society: This dimension recognises cultural and contextual differences and allows for quality to be viewed accordingly. For example, child-rearing patterns might differ and tensions between approaches that might arise can be resolved in appropriate and different ways. Or the values and principles that drive donor organisations may clash with local values and result in misguided implementations of ECD programmes. It is an important dimension especially within the South African context.

2. Resource levels and their distribution within a setting or system: Resources include both human and material. Examples of human resources are the educational level of the caregiver or the skills of the health worker. Material resources include appropriateness and accessibility of toys or equipment, provisioning of nutritious food and other health services.

3. Physical and spatial characteristics: These are associated with meeting basic needs and minimising environmental dangers. This dimension includes infrastructure and the physical environment. Safety factors and the reduction of accidents become important considerations. Do facilities allow adequate access for those with disabilities?

4. Leadership and management: Requirements differ for each level. At the top of the pyramid, for example, an important question becomes how does the adult manage the learning environment? At the setting level, this dimension encompasses the relative degree of priority given to ECD and responsiveness to issues such as provider or teacher turnover. At the support systems level, it includes such factors as responsiveness to local staffing shortages, commitment to improve professional development opportunities and capacity to monitor local delivery channels for material resources. At the subnational and national systems levels, intersectoral ECD policies require collaborative leadership and sharing of information across donor agencies, ministries and their associated subnational organisations.

5. Interactions and communications: Britto et al. (2011) stress that interactions and communications are critical to quality ECD implementation. This dimension, which also captures the nature of the communications in all settings, is applicable to all levels and incorporates communications with and between children, adults and across sectors, organisations and institutions.

How it all began: An early childhood development community of practice

In South Africa, ECD is a fragmented, complex field comprising the levels identified in the previously mentioned ecological model. Collaboration between and among these different levels is at best tenuous, despite numerous attempts over the years, by various organisations and individuals, to improve communication in the sector. In 2012, there was a renewed effort to promote and support collaboration. A group of disparate ECD stakeholders (representing the previously mentioned levels - bar the children) came together with the intention of exploring how to take the ECD sector forward, to improve collaboration between and among private and public organisations and institutions, influence policy development and to enhance ECD service delivery regardless of context. The coordinating organisation of this newly formed ECD CoP had not had any previous direct involvement with the sector.1 The CoP began in Gauteng and soon attracted members from neighbouring provinces as well as the Eastern Cape. Shortly after its inauguration, interest was expressed in the Western Cape where another ECD CoP hub was established.

The way forward was through social participation, a pivotal premise of a CoP (Wenger 1998). The lead organisation provided superb organisational as well as administrative support. Other essential enabling elements included, for example, a convivial meeting place where open dialogue was encouraged and all members had a safe space to voice their thoughts and ideas. Over time, a sense of community was established, and this was reinforced through the mutual engagement, joint enterprise and shared repertoire of the group (Lave & Wenger 1991). Through these dialogues, common threads of concern were identified, one of which was the question, what constitutes quality in disparate ECD contexts? The mutual decision to explore components of quality in greater depth became a negotiated goal (Wenger 1998).

This goal became an integral part of the CoP activities providing a needed focus, which directed the group's social energy (Wenger 1998). This has been an extremely generative process. Over a period of time, the group began to create a set of shared resources and a common understanding of what quality means in the ECD sector. There was not necessarily agreement on every aspect, but the group's strength, drawn from the CoP, enabled lively discussions about different understandings of what constitutes quality in disparate ECD contexts. Ultimately, shared understandings were negotiated allowing the process to move forward.

Initially, there was no thought that these deliberations could be the beginning of a research project. It was the evolving nature of the deliberations that led to the author asking early on in the process if the findings could be recorded and published. There was unanimous agreement. Thus, this research project grew out of an identified area of concern common to all CoP members.

The strength of the community of practice

A CoP is a social theory that explains learning and comprises a group of people who share social practices and work together towards common goals (Lave & Wenger 1991; Wenger 1998). Fuller (2007:19) acknowledges that 'people learn through their co-participation in the shared practice of the community or the "lived-in-world"'. According to Wenger (1998), an important premise of a CoP is social participation, which as a process of learning and knowing and entails four steps. These are meaning (experiencing our life and world as meaningful), practice (talking about the shared historical and social resources, frameworks and perspectives that sustain the process), community (recognising the social situations in which are our enterprises exist and encouraging competent participation) and finally identity (recognising how learning changes who we are and creates personal histories of becoming within community contexts) (Wenger 1998).

Hager (2005:23) further notes that as levels of participation increase, participants' identities and understandings become increasingly aligned to the practice and to 'acquiring the right characteristics (the products of learning)'. From the beginning, this process has been evident in the fledgling ECD CoP.

Lave and Wenger (1991) acknowledge that a CoP is a somewhat intuitive and flexible notion; it cannot be tightly defined. In addition, the concept of novices and experts is neither stable nor uniform. This has been evident in the ECD CoP, where members have brought a wide variety of differences in the richness and extent of their individual learning territories as noted by Fuller (2007). Thus, participants have followed different trajectories of participation depending upon their different experiences and perceptions in terms of their individual backgrounds and interests. Wenger himself acknowledges that disagreement, challenges and competition can all be forms of participation in a CoP. A shared practice thus 'connects participants to each other in ways that are diverse and complex' (Wenger 1998:77).

A CoP is recognisable by the presence of three dimensions, which provide a valuable framework for this research project (Wenger 1998).

Mutual engagement

Engagement requires the ability of all in the group to work towards achieving a common goal, the negotiation of meaning and to the development of a shared practice. Sharing is broadly defined and includes aspects that enable engagement, diversity and partiality. Disagreement, challenges and competition can all be forms of participation. Ensuring diversity and partiality means that both differences and similarities are recognised and valued and the unique identity of each participant is acknowledged and encourages mutual relationships. An enabling environment, which includes, for example, safe spaces to talk and simple comforts that make work more pleasant, for example, the timely arrival of snacks (Wenger 1998), is essential if mutual relationships are to be encouraged and each participant in a CoP is to find their unique place and gains a unique identity within the CoP.

Joint enterprise

Through mutual engagement, members of the CoP negotiate their joint enterprise. Participants negotiate responses to their situations creating goals for which they are mutually accountable. These negotiated goals become an integral part of practice. Total agreement is not the aim of joint enterprise, but rather 'that it is communally negotiated' (Wenger 1998:78). Deciding on an outcome and the best way to achieve this becomes a generative process. As an enterprise, it both engenders and directs social energy, encouraging action and providing a focus (Wenger 1998).

Shared repertoire

Over time, the group develops a shared repertoire. Through the joint pursuit of an enterprise, in our case quality in ECD, resources are created for negotiating meaning. The repertoire is heterogeneous and Wenger 1998 acknowledges it can comprise:

routines, words, tools, ways of doing things, stories, gestures, symbols, genres, actions, or concepts that the community has produced or adopted in the course of its existence. (p. 83)

as well as:

the individual discourses by which members make 'meaningful statements about the world'. (p. 83)

The repertoire combines two characteristics that allow it to become a resource for the negotiation of meaning. These are that it reflects a history of mutual engagement and it remains inherently ambiguous. Ambiguity does not have a negative connotation in relation to a CoP. 'It is not simply an obstacle to overcome; it is an inherent condition to be put to work' (Wenger 1998:84). It is a condition of negotiability and enables different interpretations.

The journey: Action research and a community of practice

The evolving nature of the project and the participatory nature of a CoP pointed towards a flexible research model. An action research model that would support the developmental nature of the project and could be readily aligned to the identified dimensions of a CoP seemed an appropriate choice.

The action research process

Action research supports a participatory and interpretive paradigm based on the belief that knowledge is socially constructed, subjective and influenced by culture and social interactions (Carr & Kemmis 1986). Action research is not as such a research methodology. Rather, it provides a specific lens through which to review the research process; a collaborative, participatory and empowering lens which is consistent and aligns well with the dimensions of a CoP.

Like the development of a CoP, action research is an emergent process and takes place in real-life situations (O'Brien 2001) as it addresses issues that are pertinent to participants. Context-specific knowledge is created through joint action in safe dialogic spaces by participants who have a common purpose (Koshy, Koshy & Waterman 2010; Cohen & Manion 1998). Thus, action research has a knowledge building as well as a practical component. In addition, action research develops reflection based on interpretations made by the participants. The purpose of action research is to learn through action that then leads to personal or professional development through its focus on generating solutions to practical problems (Meyer 2000).

Kemmis and McTaggart (2000:595) describe action research as a cyclical model involving a number of spiral self-reflective steps. The cycle begins with planning and is followed by doing and observing the process. The next step involves reflecting on these processes and the consequences thereof. The final step is re-planning. These four steps form part of an ongoing cycle requiring participation from all the participants and are illustrated in Figure 2.

Though the described process appears to be neat and self-contained, Kemmis and McTaggert (2000) acknowledge that in reality this is a very fluid process. In taking the process forward, initial steps might become obsolete as the participants learn from experience. As Reason and Bradbury (2008) note, a flexible approach that allows participants to adopt or adapt the models to best suit their own purposes is essential. This was the approach followed by the CoP.

When establishing the CoP, an open-ended invitation was sent to ECD stakeholders throughout Gauteng. Stakeholders comprised government officials (from different departments at both regional, provincial and national levels, including representation from the Office of the President), members of ECD training organisations, representatives from Higher Education Institutions (both state funded and private), representatives from other ECD NGOs, funders, civil society, teachers and practitioners. This open and inclusive invitation continues to be extended to any interested parties throughout the country.

In order to streamline the 'quality debate' process, a representative working committee was elected from the larger CoP forum. However, in keeping with the inclusive and participatory nature of the CoP, the invitation to attend meetings was extended to any other interested persons. The lead organisation appointed a facilitator/project manager and provided strong administrative support, which was a strong enabling element (Wenger 1998). This has resulted in an extremely supportive environment where the working committee has been able to work in a collaborative and participatory way with all contributing to the change process according to their specific knowledge and expertise.

The process has been powerful. The working committee, based on feedback from the larger forum meetings, reflects on what has been said and takes the process forward to share input at the next CoP forum. This approach loosely follows the four cyclical action research steps of plan, do, review and re-plan. Together, ideas are discussed and debated and common understandings are negotiated. The CoP members reflect on the process and provide suggestions for the way forward. This has led to interesting and rich discussions, which have been recorded at all meetings, resulting in an authentic and credible data-gathering process.

Data collection tools have included detailed field notes (recorded by the author and the administrative support team) as well as audio and video recordings of the relevant CoP discussions. In addition, during CoP meetings, participants have been divided into discussion groups to debate various aspects, and the outcomes of these deliberations have also been recorded, by participants on poster paper and by the facilitator and researcher who captured important points during feedback sessions. These deliberations have provided interesting data on different members' understandings about what constitutes quality in their contexts.

This collaborative, participatory approach has afforded all members of the CoP and the working committee the opportunity to contribute to the analysis and interpretation of findings in this ongoing study. Data were categorised and coded according to identified themes drawn from the literature and the initial findings. This too has been an extended reflective process.

The following section draws on this collaborative analysis and on the researcher's reflections to report how shifts in participants' thinking about what constitutes quality within the ECD sector have begun to emerge.

Findings and discussion: Towards a paradigm shift

The emergence of a critical dialogue

At first, conversations were low key. From the outset, there was a realisation among all members that quality is important, and during early brainstorming sessions, participants began to articulate their understandings of quality. However, they were neither able to unpack in any depth the complex nature of quality nor for whom this quality was intended. Quality was referred to in general terms and comments included broad stroke descriptions such as, 'all children require quality learning opportunities', 'there is a need to standardise ECD training' and 'the environment must be safe'.

Therefore, initially there was no articulation of the notion that quality might be an extremely nuanced and highly contested concept. However, as the shared collaboration on understandings of quality evolved (Wenger 1998), strengthened through the planned interventions of the working committee and supported by the self-reflective element that was built into each CoP meeting (Kemmis & McTaggert 2000), participants grew in confidence. As participants' insights into the various elements comprising quality began to deepen, this resulted in an increasingly richer and more perceptive dialogue, which was reflective of a shared repertoire (Wenger 1998).

The uncritical acceptance of quality as a neutral, uncontested concept began to shift. Participants began to debate its contested nature and recognise that the parameters of quality might vary from one context to another (Dahlberg et al. 2013). An animated discussion centred on possible meanings of quality in different rural as well as urban areas. Questions were asked. All contexts have challenges, but are these challenges always the same? And how do these challenges influence understandings of quality? It also became evident that as more and more critical questions were asked, there were not necessarily definitive answers. The awareness of problematising issues and asking probing questions was strengthened.

The deepening of discussions led to more searching questions such as 'could the evaluative criteria outlined in certain policy documents be equally applied to all situations?' These exchanges generated further questions supporting Peralta's (2008) claim that policies cannot be rigidly enforced across all contexts. Participants began asking 'how could policy guidelines be adapted to ensure equity for all children?' Though this joint pursuit of an enterprise (namely what is quality in ECD), which was underpinned by an emerging critical discourse and reflection, the participatory and collegial nature of the CoP was strengthened.

Shifting perspectives of quality

The emergence of a more critical dialogue was instrumental in shifting the group's thinking about quality. Initially, understandings of quality were dominated by generalised assumptions (Dahlberg et al. 2013) and the belief that most people in the forum had similar understandings of this term. Quality was generally understood to be a neutral, uncontested term.

One of the first tasks of the working committee was to explore and share various definitions of quality. Through this collective exercise, the committee and the CoP came to the realisation that quality was not a definable term but rather, as suggested by the literature, a nebulous concept difficult to 'pin down' (Dahlberg et al. 2013). Three important realisations stemmed from these discussions.

Firstly, the CoP acknowledged, as asserted by Britto et al. (2011), that when talking about quality there is always a value judgement. The debate was key and confirmed Wenger's (1998:77) assertion that participants can follow different trajectories of participation depending upon their different experiences and perceptions in terms of their individual backgrounds and interests and that a shared practice 'connects participants to each other in ways that are diverse and complex'. Though the evaluative nature of quality had been recognised from the outset, this shift in understanding enabled the CoP to explicitly acknowledge that it was not its intention to draw up a regulatory framework or another check list related to preconceived standards. Rather, the focus was developmental, for example, to assist practitioners in becoming more reflective about their own practice. It was envisaged that conversations in relation to quality would be opened in a more nuanced way and enable stakeholders to gain a greater insight into the multifaceted, complex nature of quality in their specific contexts, thereby dispelling the notion that quality in ECD is akin to the notion of 'one size fits all'.

The second realisation was that the child and child well-being are the pivotal reasons for ensuring a quality service and that all players in the sector are responsible for ensuring quality ECD roll-out. Quality is not the sole the responsibility of practitioners and training organisations. As Britto et al. (2011) have identified, there are many different stakeholders and the responsibility to ensure quality ECD service provision has to be equally distributed across the sector. However, it was agreed that because of the pivotal role of practitioners, their understandings of what constitutes quality in ECD would be the starting point for taking the process further (see ECD reflection toolkit).

Thirdly, the CoP recognised that it would be valuable to categorise the identified indicators of quality. These had been generated by the ongoing collaborative processes of the CoP. The deepening insight that understandings of quality cannot be neatly packaged into boxes and applied verbatim to any situation or context led, after much planning and reflection, to the identification of dimensions of quality and elements describing these dimensions, which formed the basis of the 'ECD quality reflection toolkit'.

Dimensions of quality: The development of an 'early childhood development quality reflection toolkit'

Identifying and refining dimensions of quality confirmed the observation by Winter and Munn-Giddings (2001) that action research can become a lengthy and time-consuming process. Deliberations, which were participatory and collaborative, were shared between the two CoP hubs Gauteng and the Western Cape. Initially, five dimensions of quality namely, practitioners, leadership and management, environment, support systems and resources were agreed upon. In order to unpack each dimension, participants were invited to identify elements that described each of these identified dimensions deepening the shared repertoire that had been established.

Even deciding upon the terms 'dimensions' and 'elements' resulted in rigorous debate. These debates were characterised by various degrees of consensus, diversity and/or conflict, common hallmarks of a CoP (Contu & Willmott 2003). Members began engaging with deeper and alternative meanings of chosen words. Should they, for example, rather be categories or characteristics? One member viewed these terms in a more traditional sense as belonging to the 'management field'. Others disagreed. The process was an invigorating one, deepening critical conversations and furthering insights into the nuanced meanings of quality. These heated debates over what comprised dimensions and elements led to the crystalisation of the intended outcome of the project, namely the development of an 'ECD reflective toolkit' for practitioners.

Though the CoP took cognisance of the levels and dimensions articulated by Britto et al. (2011), it was recognised that there was not sufficient input from practitioners on what constitutes quality practice in their contexts. It was envisaged that by obtaining greater practitioner input, the CoP would be in a stronger position to support the development of a common discourse on quality, which is informed by 'on the ground practices'.

This shift in placing the initial focus on the practitioner led to a refinement of the dimensions and eventually four were decided upon, namely, quality in leadership and management, quality in teaching and learning, quality in the ECD environment and quality in the ECD policy framework. Each of these dimensions was further unpacked into different elements, with guiding questions for each element and has become known as the ECD quality reflection tool (see Table 1).

Many elements describing each dimension were identified. However, it was decided to reduce the number of elements so that the reflection tool would not be too overwhelming. This decision was taken because many ECD practitioners work in disparate contexts, are not well qualified and find aspects of their practice challenging (DSD 2015). The ECD reflection tool ('tool') is intended to be both participatory (to allow practitioners to voice their opinions) and developmental (to assist practitioners to think about different components of quality ECD practice and the extent to which they do [or not] offer quality services). To meet this second criterion, it is envisaged that a strong self-reflective element will be built into the 'tool', which will be mediated to the practitioners. This decision was taken because of the realisation that quality is multifaceted, presents itself in different ways that are contextually driven and that there is an inextricable link between quality and practice.

Table 1 is an example of the reflection tool. It provides a comprehensive overview of the important indicators of quality that are identified in the literature.

The way forward: Extending the possibilities

To date, this has been a rich and enabling experience for many in the ECD field. To the author's knowledge, it has been one of the first successful attempts to unite a fragmented field through a participatory, collaborative approach. Perhaps a contributory factor has been the lengthy period of time, which has allowed members of the CoP to develop a sense of trust and collegiality with one another (Wenger 1998). An important contributory factor has been the negotiation of common goals. Despite some disagreement over meanings and understandings of quality, it has been an enabling experience for all participants. This is noted in the depth and richness of the dialogue and the ongoing reflective process, which has also been responsible for promoting critical dialogue (Brookfield 2005). The open-ended nature of the deliberations has allowed all participants to have a voice and spurred them to think more deeply about a number of pertinent issues facing the ECD sector, not least quality.

The ECD reflective tool is undoubtedly more than a regulatory framework. It is envisaged to have two purposes. Firstly, it is a developmental tool. Through a self-reflective process, practitioners will be encouraged to think about their understandings of quality in their specific contexts. This process will be supported by trained mediators. Secondly, it will be used as a research instrument. With their permission, practitioners will be invited to share their ideas on what is quality in their particular contexts. These responses will be recorded and the data gathered used to take the quality debate forward.

The first step in this process will be the implementation of a pilot project. This is currently being set up and will be rolled out later this year. Through the intentional research element which will underpin the pilot project, it is envisaged that should findings be positive this model (with informed adaptations) could be replicated in a larger research project with the eventually inclusion of other levels of stakeholders as outlined by the Britto et al. (2011) model.

But important questions remain and need to be borne in mind as the process evolves. The first is, 'does the tool sufficiently address the complexities and nuances of the complex multifaceted notion of quality within disparate South African contexts?' Possibly not, if compared to the Britto et al. (2011) model. However, given the current constraints (which include funding, human and material resources), the author would argue that this tool is a plausible first step.

A second question relates to the roles of context and culture. Are these made sufficiently explicit? Would it perhaps be germane to overtly acknowledge these as dimensions of quality given the current challenges in relation to social justice issues in South Africa? Children, regardless of their settings, are shaped by multiple factors (beneficial or otherwise), which are determined by a variety of contexts. However, though not an explicit dimension, culture and context have been strongly foregrounded in the tool with regard to each element.

Thirdly, are patterns of interaction between all stakeholders, for example, the child and practitioner, the child and child, health workers and practitioners, practitioners and parents, the site/centre and authorities, adequately detailed? The current tool focuses on practitioners, but is this sufficient? All adults who interact with the child, as well as state authorities and relevant policies, will have an impact on child outcomes. A first step is to share the 'tool with practitioners', but consideration will have to be given to how to expand roll-out to other stakeholders.

Fourthly, how will the model be adapted to ensure it is sufficiently comprehensive and explicit to enable evaluation of state-controlled quality at various government levels, for example, intersectoral collaboration? As Britto et al. (2011) argue, despite the importance of assessing quality at all three sublevels, the assessment at a systems level is the most challenging. Consequently, the quality of these support systems is frequently overlooked when conceptualising quality in ECD. Given the current challenges to ECD within many of these systems, a way will need to be found to ensure stakeholders at this level participate fully in the quality debates.

There is no doubt that the CoP's adoption of an action research approach supported Peralta's (2008) observation that real quality improvement happens when there is a shared understanding and agreement by stakeholders of what quality is and how it can be achieved. Through a collaborative process, there is now a negotiated agreement of important dimensions and their informing elements in relation to quality in ECD. This has been an important first step in what is envisaged to become a lengthy action research journey to deepen the discourse about what comprises quality in various ECD settings.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank the lead organisation for permission to publish this study and to acknowledge the valuable contributions of the CoP.

Competing interests

The author declares that she has no financial or personal relationships which may have inappropriately influenced her in writing this article.

References

Administration for Children and Families, 2002, Making a difference in the lives of infants and toddlers and their families: The impacts of early head start (Final technical report), Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Washington, DC.

Alexander, E., 2009, 'Understanding quality and success in early years settings/practitioners' perspectives: Full research report', ESRC End of Award Report, RES-061-23-0012, Swindon, viewed 29 April 2015, from https://www.google.co.za/#q=Alexander+E.+Understanding+Quality+in+Early+Years +Settings:+practitioners%E2%80%99+perspectives+Background

Britto, P.R., Yoshikawa, H. & Boller, K., 2011, 'Measuring quality and using it to improve practice and policy in early childhood development', Sharing Child and Youth Development Knowledge 25(2), viewed 8 May 2015, from http://www.srcd.org/sites/default/files/documents/spr_v252rev.pdf [ Links ]

Brookfield, S.D., 2005, The power of critical theory: Liberating adult learning and teaching, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA.

Carr, W. & Kemmis, S., 1986, Becoming critical: Education, knowledge and action research, Deakin University, Victoria.

Cohen, L. & Manion, M., 1998, Research methods in education, Routledge, London.

Contu, A. & Wilmott, H., 2003, 'Re-Embedding Situatedness: The Importance of Power Relations in Learning Theory', Organision Science 14(3), 283-296. http://pubsonline.informs.org/doi/abs/10.1287/orsc.14.3.283.15167 [ Links ]

Dahlberg, G., Moss, P. & Pence, A., 2007, Beyond quality in early childhood education and care: A language of evaluation, Falmer Press, London.

Dahlberg, G., Moss, P. & Pence, A., 2013, Beyond quality in early childhood education and care: Languages of evaluation, Routledge, London.

Department of Basic Education (DBE), 2009, National early learning and development standards for children birth to four years (NELDS), Department of Basic Education, Pretoria.

Department of Basic Education (DBE), 2011, National Curriculum Statement (NCS) Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS), Grades R-3, Department of Basic Education, Pretoria.

Department of Basic Education (DBE), 2015, The South African National Curriculum Framework for children from birth to four years, Department of Basic Education, Pretoria.

Department of Social Development (DSD), 2015, Draft Early Childhood Development Policy. No. 38558, Government Printers, Pretoria.

Fuller, A., 2007, 'Critiquing theories of learning and community of practice', in J. Hughes, N. Jewson & L. Unwin (eds.), Communities of practice. Critical perspectives, pp. 17-29, Routledge, New York.

Hager, P., 2005, 'Current theories of workplace learning: A critical assessment', in N. Bascia, A. Cumming, A. Dannow, K. Leithwood & D. Livingstone (eds.), International handbook of education policy, pp. 849-846, Kluwer, Dordrecht.

Irwin, G., Siddiqi, A. & Hertzman, C., 2007, Early childhood development: A powerful equalizer, Report for the World Health Organisation's Commission on the Social Determinants of Health, Human Early Learning Partnership, Vancouver, BC.

Kemmis, S. & McTaggart, R., 2000, Participatory action research. Communicative Action and the Public Sphere, viewed 8 July, from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.473.4759&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Koshy, E., Koshy, V. & Waterman, H., 2011, Action Research in Healthcare, Sage, London.

La Paro, K.M., Pianta, R.C. & Stuhlman, M., 2004, 'The classroom assessment scoring system: Findings from the pre-kindergarten year', The Elementary School Journal 104, 343-360. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/499760 [ Links ]

Lave, J. & Wenger, E., 1991, Situated learning. Legitimate peripheral participation, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Meyer, J., 2000, 'Using qualitative methods in health related action research', British Medical Journal 320, 178-181. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7228.178 [ Links ]

Moss, P. & Pence, A. (ed.), 1994, Valuing quality in early childhood services, Paul Chapman, Los Angeles, CA.

National Forum on Early Childhood Program Evaluation, 2007, A Science-based framework for early childhood policy, Center on the Developing Child, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, viewed September 2011, from http://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/reports_and_working_papers/policy_framework/

O'Brien, R., 2001, 'An overview of the methodological approach of action research', in R. Richardson (ed.), Theory and practice of action research, Universidade Federal da Paraíba, João Pessoa, Brazil, viewed 7 July 2015, from http://www.web.ca/~robrien/papers/arfinal.html

Paulsell, D., Boller, K., Hallgren, K. & Mraz-Esposito, A., 2010, 'Assessing home visiting quality: Dosage, content, and relationships', Zero to Three 30(6), 16-21. [ Links ]

Peralta, M., 2008, 'Quality: Children's right to appropriate and relevant education', Early Childhood Education Matters 110, 3-22. [ Links ]

Reason, P. & Bradbury, H., 2008, The SAGE handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice, 2nd edn., SAGE, London.

Sammons, P., Sylva, K., Melhuish, E., Siraj-Blatcford, I., Taggart, B. Grabbe, Y., et al., 2007, Effective pre-school and primary education 3-11 project (EPPE 3-11) influences on children's attainment and progress in key stage 2: Cognitive outcomes in year 5, Research Report RR828, Institute of Education, University of London, London.

Siraj-Blatchford, I. & Woodhead, M., 2009, Effective Early Childhood Programme. Early Childhood in Focus 4, Open University, London.

Wenger, E., 1998, Communities of practice: Learning, meaning and identity, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Winter, R. & Munn-Giddings, C., 2001, A Handbook for Action Research in Health and Social Care, Routeledge, London.

Woodhead, M., 1998, 'Quality' in Early Childhood Programmes - A contextually appropriate approach', International Journal of Early Years Education 6(1), 5-17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0966976980060101 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Lorayne Excell

lorayne.excell@wits.ac.za

Received: 29 Feb. 2016

Accepted: 04 May 2016

Published: 29 July 2016