Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Childhood Education

On-line version ISSN 2223-7682

Print version ISSN 2223-7674

SAJCE vol.5 n.2 Johannesburg Dec. 2015

Informing principal policy reforms in South Africa through data-based evidence

Gabrielle Wills*

University of Stellenbosch

ABSTRACT

In the past decade there has been a notable shift in South African education policy that raises the value of school leadership as a lever for learning improvements. Despite a growing discourse on school leadership, there has been a lack of empirical based evidence on principals to inform, validate or debate the efficacy of proposed policies in raising the calibre of school principals. Drawing on findings from a larger study to understand the labour market for school principals in South Africa, this paper highlights four overarching characteristics of this market with implications for informing principal policy reforms. The paper notes that improving the design and implementation of policies guiding the appointment process for principals is a matter of urgency. A substantial and increasing number of principal replacements are taking place across South African schools given the rising age profile of school principals. In a context of low levels of principal mobility and high tenure, the leadership trajectory of the average school is established for nearly a decade with each principal replacement. Evidence-based policy making has a strong role to play in getting this right.

Keywords: School principals, principal turnover, mobility, attrition, principal appointments, competency-based testing, performance management systems

Introduction

Despite both anecdotal evidence that school principals matter for learning and convincing international quantitative evidence that supports this notion, often too little policy attention is given to harnessing the benefits of school leadership for educational improvements. In reference to Chile, José Weinstein and colleagues sum up the problem well, noting that "[p]rincipals form part of a strategic sector that has not been duly explored in its potential for contributing to education progress" (Weinstein, Munoz & Raczynski 2011:298). In South Africa, however, there have been notable shifts in the past decade that raise the value of school leadership and management as critical levers for learning gains and in increasing levels of accountability within the education system. This has been expressed in amendments to legislation, statements and actions of the Department of Basic Education (DBE) and in national policy plans.

In particular, with the release of the National Development Plan (NDP) in 2012, the need to strengthen the policy framework governing principals has arguably gained traction as it explicitly identifies the importance of strengthening school leadership as a national priority (NPC 2012:309-310). The NDP proposes policy improvements for school principals in three broad areas: the principal appointment process, managing their performance and providing them with greater powers over school management (ibid).

Concurrently, quantitative research has not kept abreast with needed policy improvements governing school principals. There is a lack of empirical evidence in the local context to guide and support policy implementation in this area; this is particularly problematic when politically interested groups are likely to have convincing arguments against proposed reforms. This paper summarises evidence from a larger body of research by the author on the labour market for school principals in South Africa to contribute to the wider discourse on school leadership in South Africa (Wills 2015a). Four overarching quantitative characteristics of this market are highlighted to inform, support and debate recent policy developments involving school principals. In light of these findings, the NDP policy proposals to raise the calibre of school leadership are considered and additional policy recommendations are proposed. The intention is to identify the seeds of a better future system of policies while considering current provisions already made to improve school leadership.

International evidence on principal effectiveness

For years, a large education administration literature located primarily in the United States of America (USA) and Europe has purported that school leaders are critical to school effectiveness and student learning. For example, Leithwood, Louis, Anderson and Wahlstrom (2004) in their review of case studies noted that principals are only second to teachers in terms of their importance for student learning and school effectiveness in general. In this literature, much of the anecdotal evidence elucidating the importance of principals has unfortunately been dampened by quantitative analyses noting very small effects of leadership on school outcomes (Witziers, Bosker & Kruger 2003). These small effects are attributed to the non-representative samples used in analyses, inadequate quantitative methodologies adopted and narrow frameworks used in measuring leadership (Hallinger & Heck 1996; Robinson, Lloyd & Rowe 2008).

In the economics literature, a new and emerging evidence-base using large scale data sets and value-added models provide convincing evidence that school principals matter considerably for student learning (Branch, Hanushek & Rivkin 2012; Chiang, Lipscomb & Gill 2012; Coelli & Green 2012; Grissom, Kalogrides & Loeb 2012). Value-added models identify the additional value that principals bring to student learning after isolating out the contributions of individual teachers, the school and also the ability and backgrounds of individual students. Widely cited research by Branch et al (2012) using data on schools in Texas, suggests that highly effective principals can raise the achievement of the average student in their schools by between two and seven months of learning in a school year; ineffective principals lower achievement by the same amount. These are educationally significant effects, second only to the direct effects of individual teacher quality on student learning. But the difference between teachers and principals is that principals affect all students in a school rather than just the students a single teacher instructs. The overall impact from increasing principal quality therefore substantially exceeds the benefit from a comparable increase in the quality of a single teacher (Branch, Hanushek & Rivkin 2013). The obvious implication of this international evidenceis that the effective placement and distribution of principals across schools really matters for school effectiveness and student learning (Clotfelter, Ladd, Vigdor & Wheeler 2007; Loeb, Kalogrides & Horng 2010). Policy has an important role to play in ensuring that principals are distributed as equitably as possible across the school system, ensuring that the right principals are appointed and in raising the performance of existing leadership.

Background on policies influencing school leadership in the local context

Beyond anecdotal evidence or findings from small case studies of schools, there is little to no research that has provided any systematic quantitative evidence linking school principals or their competencies to school performance in the South African context.1 Hoadley and Ward (2009) in their review of literature on school management and leadership reiterate earlier remarks by Bush, Glover, Bischoff et al (2006) that our understanding is limited in terms of how the actions and behaviours of school leaders in South Africa are contributing to or detracting from school functionality, particularly with respect to producing learning outcomes. One reason for this is that reliable quantitative research is hampered by the lack of representative data linking teachers and principals to students over time.

In the policy environment, however, there have been some interesting developments during the past decade. With promulgation of the Education Laws Amendment Act in 2007, more accountability for school performance was placed in the hands of principals as legislation required of them to plan for academic improvements in schools and report progress against school plans (RSA 2007). A recent example of how this legislation is used at a provincial level to improve accountability is a gazette released by the Western Cape Government Department that imposes binding performance indicators on schools, holding principals responsible for setting performance targets and implementing plans to achieve these targets (PGWC 2015). However, policies of this nature may not produce the kind of behavioural changes required for school improvement. There is considerable evidence that the majority of principals are complying and that they are developing improvement plans and performance reports in line with legislation (Taylor 2014). An analysis of the School Monitoring Survey of 2011 indicates that as many as 85% of schools had school improvement plans, 78% had academic improvement plans and a further 94% had academic performance reports (RSA DBE 2014a:24). Whether these documents are actually meaningful, of good quality and implemented to improve learning outcomes is another question. Accountability mechanisms must have clear links to school improvement rather than merely imposing another compliance burden on the system (Pritchett 2013; Taylor 2014). This should be a key consideration in the design and implementation of performance management systems affecting principals' work.

For the most part, principals' performanceis still assessedin terms of the Integrated Quality Management System (IQMS) agreed to in 2003 (ELRC 2003). This system has a number of weaknesses in terms of both its design and implementation, which impedes its ability to introduce the levels of accountability initially intended. It has not provided sufficiently clear standards against which to assess the work of principals (Smit 2013). Attaining good ratings has been too easy (RSA DBE 2012:22). Moreover, many principals have often not been evaluated by their immediate supervisors (circuit managers) as initially proposed by the agreement: in the sample of schools visited by IQMS moderators in 2011/12 only 41% of principals had been evaluated by their circuit manager (RSA DBE 2012:44).

Finally, the 'carrots and sticks' of IQMS are arguably ineffective in inducing changes in behaviour. In particular, its capacity to introduce notable threats to job security is stifled in the face of stringent labour legislation and substantial union involvement which create significant barriers to dismissals. Van Onselen (2012) indicated that between 2000 and 2011 a total of ninety-seven educators were permanently struck off the register of the South African Council of Educators - an average of less than ten a year. However, estimations based on 2011 termination data from the DBE point to a much larger number of dismissals - roughly 350 per year across provincial departments. As a proportion of educators this is arguably still low at about one in 1 000 educators although this ratio varies across provincial departments. Using the same data, roughly twenty-two principals were dismissed in 2011, less than one in a 1 000 principals in South Africa. As a point of comparison, in the USA for example, roughly twenty-one in 1 000 teachers are dismissed annually for poor performance (Aritomi, Coopersmith & Gruber 2009).

The national DBE has made a number of statements pertaining to holding principals accountable for school performance through the introduction of new performance contracts (Khumalo 2011; Phakathi 2012). A draft performance agreement for principals was proposed by the DBE in June 2011 that would hold principals accountable for the performance of teachers and also student test results. Unfortunately, as explained in a succinct description by Louise Smit (2013) of these Educational Labour Relations Council (ELRC) negotiations during the past ten years, introducing more effective performance management for principals has been resisted by teacher unions, and the June 2011 proposal was withdrawn in 2012 (ibid).

In the context of weak existing accountability systems for school principals, the NDP reiterated the need for introducing performance contracts for principals and deputy principals aimed at improving their performance and targeting their training needs. It also advocated replacing underperforming principals; a proposal supported by current legislation. The Education Amendment Act of 2007 makes provision for tackling poor leadership in poorly performing schools through i) identifying underperforming schools, and ii) taking action to either counsel the principals of these underperforming schools or to appoint academic mentors to take over their functions and responsibilities for a period of time as determined by provincial Head of Departments (RSA 2007). In addition, the Employment of Educators Act makes provision for the dismissal, after an inquiry, of an educator who is unfit for the duties attached to his or her post. However, there are variations in the extent to which this is legislation is implemented. For example, in the Western Cape, an educator is six times as likely to be dismissed compared to an educator in Limpopo.

Importantly, the NDP also stresses the importance of making the right principal appointment at the outset. Nationally, appointment processes and short-listing criteria governing teacher and principal appointments are expressed in the Personnel Administrative Measures (RSA DoE 2003). After short-listing applicants who meet minimum appointment criteria, interviews are conducted at schools by a panel consisting of parents, the principal, a department representative (who may be the principal) and a union representative whose role is only to 'observe' that due process is followed. The panel then submits recommendations of their choice of candidate to the head of department who makes the final appointment decision (ibid:21). In recent years, various reports have highlighted the undue influence of unions in selection processes beyond mere observation. There have also been allegations of bribery, cronyism and concerns that School Government Bodies (SGBs) do not possess the necessary capacities to interview and select the right person for the job (Taylor 2014; NPC 2012; City Press 2014). In improving the appointment process for principals, the NDP recommends reducing the undue influence of unions in the appointment process while providing increased support to SGBs to fulfil their general mandate.

It also suggests raising entry level requirements for principals where a prerequisite for principal promotion should be an Advanced Certificate in Education (ACE) in School Management and Leadership. As expressed in the Personnel Administrative Measures, observed credentials including qualifications and years of experience are the key criteria guiding principal appointments (RSA DoE 2003). However, these criteria do not substantially differ from that of an entry level teacher. In addition to raising the minimum entry level criteria for principal appointments, the NDP proposes augmenting the appointment process with competency-based assessments for principal applicants to determine their suitability and identify the areas in which they would need development and support. This in turn will limit the undue influence of unions and other interested parties in the appointment process, especially where an independent contractor manages this process.

These NDP proposals are the latest in a number of attempts to raise the calibre of school leadership. For example, raising minimum criteria for entry into principal positions was considered as early as 2007 through the initial introduction of the ACE programme in School Management and Leadership and its later review and redesign (Bush et al. 2009; NPC 2012). More recently, the DBE has set in motion a series of additional actions towards implementing policies in line with the NDP recommendations. In August 2014, a national gazette of a draft policy stipulating the Standard for Principalship was released for public comment (RSA DBE 2014b). The document outlined the qualities and competencies school leaders should have. As noted by Christie (2010), the setting of 'professional standards' for principals forms part of the broader drive for accountability. These standards are likely to form the framework on which competency tests and any forthcoming improved performance management systems for principals will be based. Moreover, provincial education departments in the Western Cape and Gauteng have already embarked on a process of piloting competency tests in the principal appointment process (RSA 2015). The DBE's commitment to this goal was also expressed in their 2015 Annual Performance Plan where the number of new principal appointments involving competency-testing was introduced as a key performance indicator in tracking the attainment of the DBE goals expressed in their Action Plan 2019: Towards Schooling 2030 (RSA DBE 2015a; RSA DBE 2015b).

Despite the steps taken to accelerate policy developments for increased principal accountability, progress toward implementing these goals has been slow, particularly with regards to improving the principal appointment process. As presented in the next discussion, a substantial number of new principals have been appointed in recent years, but for the most part this has occurred in the absence of new legislated policies governing their appointment.

Data

The empirical results summarised in this paper have been drawn from an analysis of a panel data set of schools and their principals, constructed by matching South African payroll data on educators (referred to as Persal data) to administrative data collected on schools including the Annual Survey of Schools data, Snap survey data as well as the EMIS master list of schools. Payroll data of individuals working in the public education sector was made available to the author for the months of September 2004, October 2008, October 2010 and November 2012.2

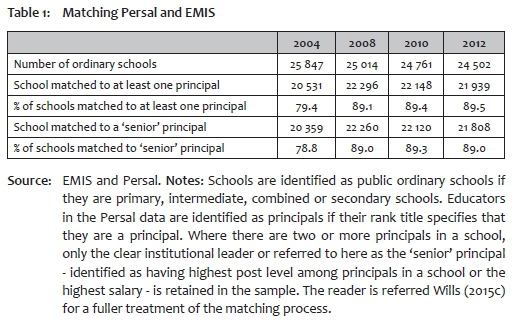

Connecting the administrative data sets is a challenging task. EMIS and payroll data are managed and collated by two distinct national departments and the different data sets were never designed to be used for analyses over time or for linking them together. Furthermore, systems for identifying schools are not the same across the two data sets. Payroll-school links are made through matching across two codes in payroll that point to school establishments. For a more comprehensive discussion of the matching process the reader is referred to Wills (2015b). For the total school sample, the number of successful matches is identified in Table 1. The number of ordinary public schools for each year is identified in the EMIS master list followed by the number of schools that are matched to at least one principal in payroll. In some schools there may be more than one principal identified in payroll but the analysis that follows is concerned with the main school leader. A small number of principals that could not be distinguished as the clear institutional leader in a school using the payroll post level rankings or salary indicators are excluded from the analysis. For each year, between 79% and 89% of ordinary public schools in EMIS are matched to principals, with the number of successful matches increasing in recent years.

Four characteristics of South Africa's cohort of principals are identified using the data which are relevant to the policy discussion on adopting more effective mechanisms for appointing principals, managing their pay and performance (Wills 2015a).

Characteristic one: An aging profile of school principals

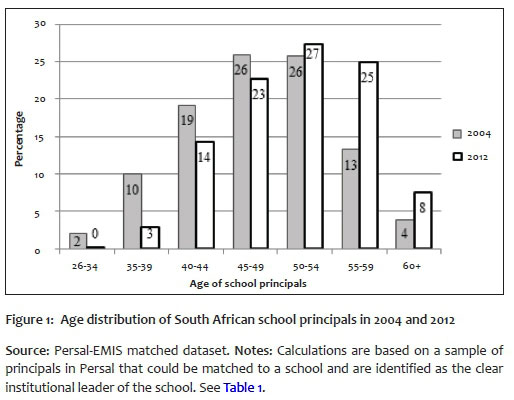

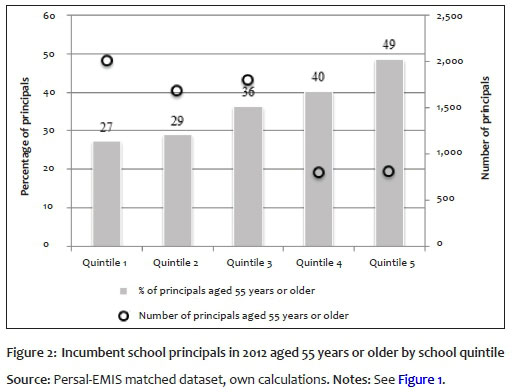

Internationally, teachers and principals are getting older and South Africa is no exception in this regard (Pont, Nusche & Moorman 2008). The average age of principals in 2004 was forty-eight years. In 2012 this average had increased to fifty-one years, closely approaching the average age at fifty-three years for principals in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries (OECD 2014). Figure 1 compares the age distribution of principals in 2012 to that in 2004. Whereas 17% of school principals were aged fifty-five or older in 2004, two thirds were this age by 2012. In absolute terms, if almost a third of principals were fifty-five years or older in 2012, and we assume that they are likely to retire at age sixty,3 as many as 7 000 outgoing principals may have to be replaced between 2012 and 2017. As a yearly average, this equates to about 1 100 to 1 200 principal replacements for retirement per year over this period, compared to a yearly average of about 350 to 500 principals required to replace retiring principals between 2004 and 2008. Proportionally more principal replacements will need to take place in wealthier schools given the differences in the age profile of principals across schools. In 2012, nearly a half of Quintile 5 schools had incumbent principals aged fifty-five years or older as opposed to 27% of Quintile 1 schools as identified in Figure 2. The demand for new principal replacements is considerably higher in poorer schools simply because there are more poor schools. Despite use of the term 'quintile' in the ranking of school wealth by the DBE, there is an unequal share of schools represented in lower quintiles.

The public education system is clearly facing a substantial number of principal retirements. Finding suitable replacements and managing leadership transitions poses a notable challenge for schools and provincial administrations. An additional complication in finding suitable principal replacements relates to the uneven age profile of teachers. In the recently released report on teacher demand and supply by the Centre for Development and Enterprise, the uneven spread in the age profile of teachers is apparent which has implications for the future supply of school leaders. The report provides an estimated teacher age profile in 2025 on the basis of the 2013 age profile of educators in South Africa, attrition rates and patterns of teacher retirement (CDE 2015). The report notes that there is a dip in the current teacher population at around thirty to thirty-four years who will move through the system. By 2025, the smallest number of teachers will be forty to forty-four years old, which is

[...] the age at which teachers typically have sufficient experience to be eligible for senior management positions, such as principal, deputy-principal and HoD. The very small pool from which they can be drawn means that less experienced teachers may have to be promoted to those positions.

CDE 2015:18

This statement, however, is based on the premise that experience is a valid indicator of principal quality and should guide the selection process.

The retirement of principals poses challenges for education planners (Wills 2015c) but it also provides an opportunity to raise the calibre of school leadership through the right appointments. As explained in a report on improving school leadership in OECD countries,

[t]he imminent retirement of the majority of principals brings both challenges and new opportunities for OECD education systems. While it means a major loss of experience, it also provides an unprecedented opportunity to recruit and develop a new generation of school leaders with the knowledge, skills and disposition best suited to meet the current and future needs of education systems.

Pont, Nusche & Moorman 2008:29

Characteristic two: The unequal distribution of principals across schools in terms of qualifications and experience

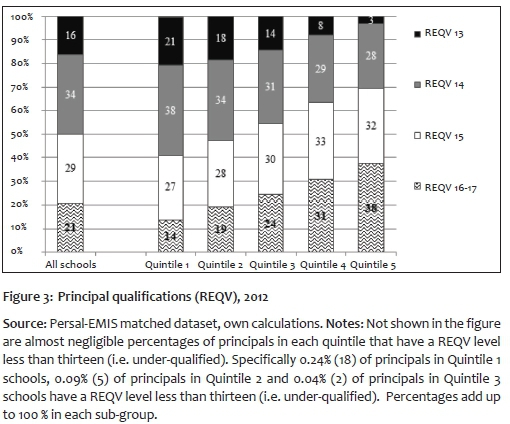

A defining feature of South Africa's labour market for principals is that they are unequally distributed across schools with less qualified and less experienced principals typically represented in poorer schools (Figure 3).

In the education payroll data, qualifications of educators are identified using the Relative Educational Qualifications Value (REQV) system. This is a value ranking on a scale of ten to seventeen, where the determination of the REQV ranking is based primarily on the number of recognised full-time professional or academic years of study at an approved university, technikon or college of education, while taking into account the level of school education attained (RSA DoE 2003). Higher rankings are assigned to more advanced qualifications with implications for promotions, the status of contracts and salary levels. A REQV level ten, for example, is associated with having at most a Grade 12 academic qualification and no teachers' qualification. A REQV level seventeen is equivalent to having Grade 12 plus seven years relevant training which includes at least a recognised master's degree. The minimum requirement for entry into a permanent teaching post is REQV level thirteen - a Grade 12 qualification plus three years of relevant training which is typically a three year teaching diploma.4 In the figures presented, the quintile ranking of schools provided by the DBE is used as an imperfect measure of wealth status as no background data on schools or their students was available in the administrative data used. Identified as the poorest, Quintile 1 to 3 schools are non-fee paying while Quintile 4 and 5 schools receive much smaller state funding allocations but are left to determine the amount of school fees charged in consultation with parents.

In 2012, roughly 34% of principals matched to schools had REQV level fourteen signalling a four year bachelors' degree, 29% had REQV level fifteen and 21% were very well-qualified with REQV level sixteen or seventeen, equivalent to a post-graduate degree. A further 16% of schools had principals with a qualification ranking equivalent to an entry level requirement for a permanent teaching post (REQV level thirteen). The poorest schools are significantly less likely to have well-qualified principals than wealthier schools. For example, 38% of Quintile 5 schools have very well-qualified principals compared with only 14% of Quintile 1 schools.

In part, this unequal distribution is attributable to historically imposed policies that matched teachers and principals to schools along racial lines. During apartheid, the race of teachers and school leaders would have been matched to the race of the students in their schools with separate education departments formed to administer these segregated schools. Moreover, policies also favoured the educational advancement of the white race group over others, which meant that white educators would have been exposed to more training and academic opportunities than educators of other races. Although racial controls on schooling were lifted in 1994, there have been inertial influences of these state imposed controls on the patterns by which teachers and principals are positioned (otherwise referred to as 'sorted') across schools. This pattern is particularly strong in the case of principals given that the average principal in 2012 entered the education system twenty-five years previously, seven years before democratic freedom. Due to the fact that race had historically been tied to wealth and privilege, it is expected that less qualified principals are overrepresented in the poorer parts of the schooling system.

While inequalities in the qualifications of principals across school types may have been attributed to historically imposed policies, in the absence of apartheid controls on principal sorting, newly appointed principals in poorer schools continue to have substantially lower qualifications than those appointed in wealthier schools. This is shown in Figure 4 which presents the qualifications by school quintiles of principals newly appointed during the period 2008 to 2012 (incoming) and those of principals exiting the system (outgoing) over the same period. A second feature of the figure is that, with the exception of Quintile 5 schools, newly appointed principals have fewer qualifications than outgoing principals. Wealthier schools have historically had more qualified principals and continue to appoint increasingly better qualified candidates in comparison to poorer schools.

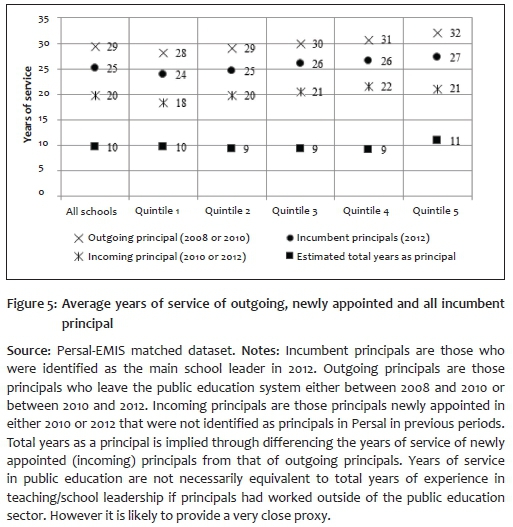

The observed differences in appointment across poorer and wealthier schools are mirrored in the years of service of newly appointed principals. The only available measure of experience is 'years of service'. This is not the same as total work experience in the education sector as individuals may have moved in and out of the public education sector. Nevertheless, it provides a close proxy for total experience in the teaching profession. The typical educator in South Africa has roughly twenty years of service before accessing a principal position for the first time, as shown in Figure 5. On average they will serve ten years in a principal post before exiting the system. In the poorest (Quintile 1) schools, however, principal positions can on average be reached three years earlier compared with positions in Quintile 4 and 5 schools. Access to principal promotion posts in poorer schools is therefore possible with lower qualifications and fewer years of experience. This finding holds even when controlling for compositional differences (including primary and secondary level, school size and teacher numbers) across schools.

In designing policies to address this inequity, it is necessary to distinguish between two factors underlying principal sorting. Firstly, sorting is likely to be driven by the preferences of individuals for posts in wealthier schools. There may simply be a larger pool of good candidates available for posts in wealthier schools, particularly where teachers are more qualified in these schools. Secondly, there may be variations in the recruitment and selection processes across schools where wealthier schools impose more stringent appointment criteria and/or are more likely to follow due process. More research is required to disentangle how much each factor weighs on the patterns observed; however, policies would need to be targeted at both factors to improve the initial matching of principals to schools.

Inequities in the observed credentials of principals across different parts of the schooling system point to resourcing inequities and are clearly important to track given the historical legacy of apartheid policies. Moreover, if qualifications and experience are indicators of principal quality, the sorting patterns noted above pose concerns about the capacity of school leaders in the underperforming part of the school system to execute their roles and responsibilities. The question as to whether traditional credentials actually signal principal quality in South Africa is considered in the discussion that follows.

Characteristic three: Traditional credentials do not signal principal quality

Internationally, credentials such as qualifications and experience are usually the key criteria used in the recruitment of teachers and principals and in determining their pay. South Africa is no exception in this regard. However, international studies provide mixed evidence that credentials have any bearing on actually raising student performance in schools (Ballou & Podgursky 1995; Clark, Martorell & Rockoff 2009; Eberts & Stone 1988). This is consistent with the evidence on whether teacher credentials provide an explanation for differences in student performance across schools (Clotfelter, Ladd & Vigdor 2010; Hanushek 2007). For example, in America both Eberts and Stone (1988) and Ballou and Podgursky (1995) found a negative correlation between school performance and principal education, as measured by advanced degrees and graduate training. Using a methodology that allows them to obtain more reliable estimates of how principal characteristics impact on student test scores than prior studies, Clark et al (2009) found little evidence of any relationship between school performance and principal education or pre-principal work experience. However, they did find a positive relationship between experience in a principal role and school performance as measured by mathematics test scores and student absenteeism.

Identifying whether observed credentials are a signal of quality has implications not only for designing effective selection processes, but it also has direct fiscal implications. Across the board, the qualifications of principals in South Africa have been rising. In just four years, between 2008 and 2012, about 3% more schools had principals with REQV level sixteen to seventeen, roughly equivalent to a post-graduate degree. However, in the majority of schools the rise in qualifications of principals is not due to the appointment of more qualified replacement principals compared with outgoing principals. Rather, incumbent principals are acquiring higher level qualifications while on the job through in-service training. This was evident in Figure 4 which compared the qualifications of newly appointed principals and those of principals exiting the system during the period 2008 to 2012. A similar pattern is observed with respect to teachers in general in South Africa who build up their qualifications on the job, often over many years (CDE 2015). While some may consider this a positive indicator of professional development and a signal of leadership quality improvements, the acquisition of higher level qualifications is not necessarily a route to improve skills but a way to advance along the salary schedule. Unless qualifications improve the proficiencies of school leaders this is unlikely to translate into improvements for the core outcome of concern, student learning. Instead, the system is at risk if principals access higher salaries with higher qualifications but fail to match their increased cost with added value, for example through engaging in positive behavioural change, increased responsibilities or raising their performance.

In a working paper by the author that the present discussion draws from (Wills 2015a), an attempt is made to determine whether principal credentials, as measured by REQV levels and years of service, have an effect on school performance in South Africa. It is important to highlight that there are various challenges associated with estimating reliably how principal credentials are related to school performance. Different types of principals are attracted to different types of schools. Moreover, certain principals may attract or be attracted to different types of students. By exploiting the longitudinal nature of the panel dataset constructed for the study, an attempt was made to control some of these patterns of sorting to schools that may bias estimates of how principal characteristics affect school performance. A subset of the matched payroll-EMIS data set was used for the estimation, limiting the sample to schools that offered Grade 12 in 2008, 2010 and 2012 and could be connected to school matriculation examination outcomes in these years. The author drew on a school level examination series dataset constructed by Martin Gustafsson in modelling the impact of South Africa's 2005 provincial boundary changes on school performance (Gustafsson & Taylor 2013).

The results showed that in the majority of schools (Quintiles 1 to 3) principal credentials, as measured through REQV levels and years of service5, appear to have little observable impact on matriculation outcomes, specifically schools' percentage pass rate in the National Senior Certificate examination and the average mathematics score out of one hundred obtained by Grade 12 learners who take Mathematics. The results do not imply that school principals do not matter for school performance, but rather that the value they bring to schools is not signalled through their observed credentials as captured in the education payroll data. Due to the potential concern that REQV levels are not good measures of qualifications (Welch 2009), one is cautioned in implying that the educational qualifications of principals are not important for their performance. What is clear, however, is that the REQV level system is not an effective signal of principal quality in the majority of schools. While this estimation is still subject to some limitations, this is an important finding with implications for the design of recruitment policies and pay schedules.

Characteristic four: Low levels of mobility and high tenure

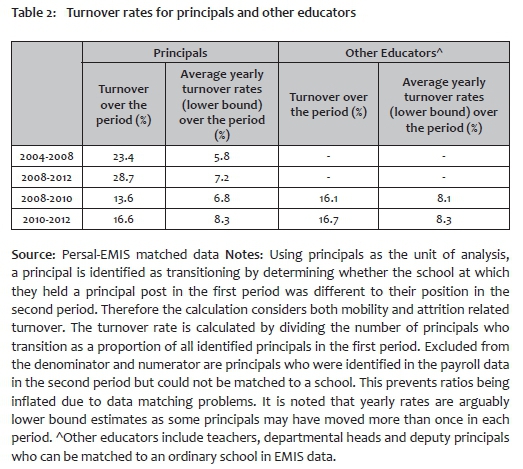

The fourth feature of South Africa's labour market for principals is low levels of turnover. Although this has started to change in recent years, principal turnover rates, which include both attrition and mobility related movements, have historically been low. The average rate of turnover among principals ranged between 5% - 8% between 2004 and 2012, as reflected in Table 2. These turnover rates are not dissimilar to those observed among teachers in general6; but compared to employee turnover benchmarks in the local public sector and internationally they are comparatively low. For example, using twelve months of public sector payroll data over a one year period, Pillay, De Beer and Duffy (2012) calculated annual employee turnover rates across thirty-three South African public sector departments that range between 9% - 32%. As an international benchmark, about 20% - 30% of public school principals leave their positions each year in the United States (Beteille, Kalogrides & Loeb 2012; Miller 2013:71).

A key reason for low levels of principal turnover is that principal moves within the system are uncommon. Instead, the majority of the turnover is accounted for by attrition (i.e. moves out of the public education system). Between 2004 and 2008 attrition accounted for two-thirds of principal turnover. This rose to three-quarters between 2008 and 2012 due to rising retirement-related turnover. With little churning across schools, principal tenure among incumbent school principals closely follows their total years of principal experience. In the Verification-ANA 2013 questionnaire presented to roughly 2 000 school principals from a nationally representative sample of schools, principals were asked about their years of principal experience and tenure as a principal at their current school. The median years of total principal experience was nine years, only one year more than the median total years served in their current school.

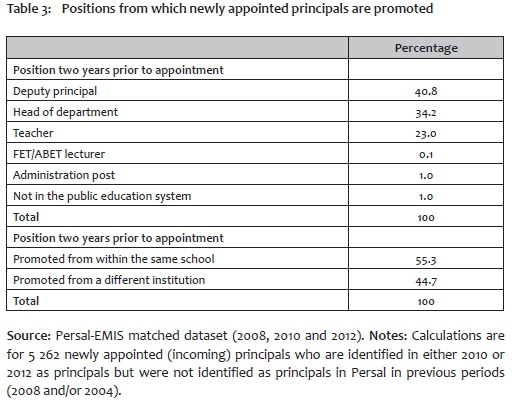

An added feature of the low levels of mobility in the sector is that over half of newly appointed principals (55%) are promoted from within the same school. Table 3 identifies the position of principals in the data two years before they are identified as newly appointed principals. As expected a large proportion of newly appointed principals (41%) are promoted from deputy principal positions, and a third from head of department positions. Surprisingly, as many as 23% of newly appointed principals were only in a teaching post two years prior to their appointment as principal.

There are likely to be various reasons for low levels of principal mobility, such as low relocation benefits, language and cultural factors or nepotistic appointment arrangements. International literature also indicates that low mobility may be strongly related to a lack of accountability measures affecting principals. When hard-stakes performance management systems are in place with principal performance evaluations based on school performance, job security concerns incentivise principals to move schools. For example Clotfelter et al (2007) found that in North Carolina in the USA, there was a sharp increase in rates of principal turnover in response to the introduction of the state's test-based accountability system. To avoid low performance ratings, principals are more likely to move from worse to better performing schools, which usually involves moving from poorer to wealthier schools (Branch et al 2012; Gates, Ringel, Santibanez et al 2006; Loeb et al 2010).

Where the current design of performance management systems for principals in IQMS is weakly linked to threats to job security or very favourable monetary rewards, it is unlikely to drive mobility related principal moves. Yet evidence suggests that there may be other incentives at play that affect mobility patterns. A combination of econometric and descriptive evidence using the payroll-EMIS matched dataset indicates that principals may view positions in slightly wealthier schools or urban schools as more attractive options. This is not surprising if associated working conditions in these schools are better than in poorer or rural schools. Furthermore, school-to-school transfer patterns suggest that principals seek positions in larger schools as opposed to smaller ones. This is not surprising since salaries are linked not only to qualifications but to school size.

The race of the principal relative to the race of the student composition of the school also appears to influence patterns of transfer in South Africa. In the literature from the United States, the likelihood that a principal or teacher leaves a school rises as the racial composition of the student body deviates from that of the principal or teacher (Gates et al 2006; Hanushek, Kain & Rivkin 2001). In the South African context, there is also evidence that the racial composition of students relative to the principal is significantly associated with their decision to move. Black principals are more likely to move out of a school if there is a non-majority black student enrolment. White principals are more likely to move out of a school when the majority race composition of the school is black. In this respect, historical patterns of principal sorting to schools along racial lines continue to persist through patterns of principal transfers.

In summary, this section has identified that the South African labour market for principals is characterised by low levels of mobility. With low numbers of school-to-school transfers, principal transfers within the system do not pose a substantial threat to widening existing inequalities in the distribution of principals across schools. However, among those principals who do move within the system there appear to be incentives operating in the direction of increasing existing inequalities, specifically where race informs transfer decisions.

Discussion: Evidence informing policy

The preceding discussion has highlighted four overarching characteristics of the labour market for principals. In summary:

1. The age profile of principals has been rising, indicating the need for a substantial number of principal replacements in the near future. While proportionally more retirements are taking place in wealthier schools, the absolute demand for principal replacements is highest in the poorest schools. Moreover, the demand for replacement principals is particularly large at the primary and intermediate school level comprising over 60% of anticipated principal replacements due to retirement.

2. Principals are unequally distributed across schools with less qualified and less experienced principals represented in greater proportions in poorer schools. Initial matching of new principals to schools continues to persist in line with historical patterns.

3. There is some evidence that in the majority of schools principal credentials as measured in the educator payroll data, namely REQV levels and years of service, have little observable positive relationship with school performance as measured by matriculation outcomes. This does not imply that qualifications are not important. Rather the value principals bring to schools is not signalled through their observed credentials as measured, specifically, in the educator payroll data.

4. Despite rising levels of retirement related attrition, low levels of mobility and consequently high levels of average tenure characterise this market. Although the number of within sector transfers is low, there is some evidence that among principals who move from school to school, transfer patterns tend to exacerbate existing inequalities.

In a sector characterised by low levels of mobility and high levels of tenure, policies should be aimed at improving the initial match of principals to schools while developing the effectiveness of incumbent principals over their length of tenure. Moreover, where observed credentials provide weak signals of quality, policies guiding the selection and rewarding of principals should extend beyond qualifications and experience to identify expertise and skills that better signify quality.

In light of this, the relevance of proposed policies in the National Development Plan (NDP) to improve the calibre of school leadership is considered, and for ease of reference summarised in Table 4. The findings strongly support proposals to i) introduce competency-based assessment in the appointment process and ii) implement performance management for incumbent school principals aimed at increasing the quality of leadership provided to schools. However, the design and implementation of these policies are important to ensure that they generate the desired outcomes and this warrants additional research. In brief, some issues are discussed in this regard.

Competency-based testing should be designed to identify competencies that distinguish better quality school leaders from weaker ones. Currently little evidence exists on the types of skills or attributes that matter for school performance in the South African context. What is clear from both local and international literature, is the need for principals with a strong instructional focus who lead the activities of the school to focus on the core business of teaching and learning (Bush et al 2006; Hallinger & Heck 1996).

Improving performance management systems for principals, either in the existing IQMS or in designing a replacement system, is complex. It involves issues such as what performance criteria are monitored, who evaluates performance and how it is rewarded. Performance must be assessed in terms of standards for leadership and managerial behaviours that are logically linked to learning improvements in schools. Alternatively, performance may be directly measured by improvements in student learning in the schools principals lead. A clear weakness with the existing IQMS is that, although management and leadership evaluation criteria are included, the evaluation of a principal's role is not treated distinctly from his or her role as teacher (Smit 2013). IQMS is also not linked to measurable indicators of school performance. Of course, identifying suitable learning indicators against which to measure performance is a notable challenge in designing a new system. While the Annual National Assessments (ANA) provide a very useful mechanism for diagnosing learning deficits (and are an important addition to accountability more broadly), in their current form they have shortcomings. Progress is needed in ensuring that ANAs become a truly standardised test before considering them as measures for tracking learning improvements over time, let alone rewarding schools and principals for these improvements. Currently ANAs are not designed to be compared over time (John 2012; Taylor 2012). Moreover, linking principal performance to student test scores, for example, poses potential threats of introducing perverse incentives. For example, principals may move out of schools with underperforming students and transfer to more attractive schools. This pattern of transfer typically involves moving out of poorer schools, thereby aggravating existing inequalities in the distribution of principals and reducing the pool of applicants for posts in underperforming schools.

Inimplementing performance management systems there are also notable challenges. Arranging performance evaluation meetings with principals in more than 24 000 public schools is likely to pose logistical problems. This was identified as a clear challenge in the implementation of the existing IQMS, providing few guarantees that direct line managers will conduct evaluations in the future (RSA DBE 2014c; RSA DBE 2012). Increased accountability for principals goes hand-in-hand with improvements at a district level to support and monitor schools (Elmore 2000). Finally, performance management is likely to be met with considerable resistance not only from teacher unions, but from principals themselves if they feel that the system is unfair or that there are too many variables affecting their performance that they feel are outside of their control (Heystek 2015). These concerns are expressed in a context where they have no control over hiring and firing of those they are appointed to lead.

Improved performance management systems must be packaged carefully to minimise resistance. Proposals are likely to be more palatable where performance evaluations are strongly connected to training and mentoring to actively address areas of non-performance. More generally, carefully crafted packages of policies are necessary to ensure that the individual aims of each are realised. This is particularly relevant in reference to the NDP proposal to delegate more authority to school leaders. Hanushek and Woesmann (2007), in reviewing evidence on strategies for school improvement, noted that providing increased decision-making authority to schools has been shown to have significant impacts for improving school outcomes, even in developing country contexts. They caution, however, that "Local autonomy without strong accountability may be worse than doing nothing" (ibid:74). The NDP does suggest that more autonomy be given to school principals conditional on exhibiting a level of leadership quality. This indirectly implies that this policy be packaged with performance management where a rewarded outcome of assessments is increased autonomy.

The NDP proposal to raise minimum principal qualification criteria to having an Advanced Certificate in Education (ACE) in School Leadership and Management is not strongly supported by the available evidence. Research has previously been conducted into evaluating the effectiveness of the ACE programme in raising the quality of school leaders (Bush, Duku, Glover et al 2009). While the report makes many positive qualitative links between the programme and its ability to raise principal competencies, there was no conclusive improvement in the performance of the schools led by these ACE trained graduates. It is cautioned that unless the revised ACE programme results in improved leadership and management competencies it is unlikely to act as a useful indicator of principal quality. It might rather have the unintended consequence of reducing the available pool of potential principal candidates to those who have obtained this certificate. Already the pool of suitable principals is likely to be too small to meet the replacement demand for the substantial number of retirements taking place. It is noted that the ACE programme makes useful provisions for forms of mentoring and on-site training for school principals in raising leadership quality. In light of the evidence presented, the extensive number of principals who are retiring, particularly those from well-functioning schools, provides a pool of available trainers and mentors for growing numbers of newly appointed principals.

An additional policy that was not considered in the NDP, and is relevant in light of the evidence provided, is introducing monetary incentives to improve the available pool of principal candidates applying for posts in hard-to-staff and poor performing schools. Directing a pool of good applicants to poorer schools is particularly important not only for improving the distribution of principals across schools, but also to meet a much larger demand for replacement principals in these schools.

In conclusion, this research has attempted to contribute to an evidence base on principals to inform policy to raise the quality of school leadership and management. It may take many years before more effective systems for the appointment and performance management of principals are finalised and implemented. Nevertheless, these are urgent priorities in light of the substantial number of principal replacements to be made in schools both currently and in the near future. With each principal placement, the leadership trajectory of the average school is established for almost a decade. Evidence-based policy making has a strong role to play in getting this right.

References

Aritomi, P., Coopersmith, J. & Gruber, K. 2009. Characteristics of Public Schools in the United States: Results for the 2007-2008 Schools and Staffing Survey. Washington, DC: National Centre for Education Statistics. [ Links ]

Ballou, D. & Podgursky, M. 1995. What Makes a Good Principal? How Teachers Assess the Performance of Principals. Economics of Education Review, 14(3):243-252. [ Links ]

Beteille, T., Kalogrides, D. & Loeb, S. 2012. Stepping stones: Principal career paths and school outcomes. Social Science Research, 41:904-919. [ Links ]

Branch, G., Hanushek, E. & Rivkin, S. 2012. Estimating the Effect of Leaders on Public Sector Productivity: The Case of School Principals. NBER Working Paper Series No 17803. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. [ Links ]

Branch, G., Hanushek, E. & Rivkin, S.G. 2013. School Leaders Matter. Education Next. Retrieved from www.educationnext.org (accessed 1 June 2015).

Bush, T., Duku , N., Glover, D., Kiggundu, E., Kola, S., Msila, V. & Moorosi, P. 2009. External Evaluation Research Report of the Advanced Certificate in Education: School Management and Leadership. Pretoria: Department of Basic Education. [ Links ]

Bush, T., Glover, D., Bischoff, T., Moloi, K., Heystek, J. & Joubert, R. 2006. School Leadership, Management and Governance in South Africa: A Systematic Literature Review. Johannesburg: Matthew Goniwe School of Leadership and Governance. [ Links ]

CDE (Centre for Development and Enterprise). 2015. Teachers in South Africa: Supply and Demand 2013-2025. Johannesburg: The Centre for Development and Enterprise. [ Links ]

Chiang, H., Lipscomb, S. & Gill, B. 2012. Is School-Value Added Indicative of Principal Quality? Working Paper. Princeton, NJ: Mathematica Policy Research. [ Links ]

Christie, P. 2010. Landscapes of Leadership in South African Schools: Mapping the Changes. Educational Management Administration and Leadership, 38(6):694-711. [ Links ]

Christie, P., Butler, D. & Potterton, M. 2007. Schools that Work: Report of the Ministerial Committee. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

City Press. 2014. How Sadtu sells its posts. Retrieved from http://www.news24.com/Archives/City-Press/How-Sadtu-sells-its-posts-20150429 (accessed 6 May 2015).

Clark, D., Martorell, P. & Rockoff, J. 2009. School Principals and School Performance. CALDER Working Paper Series 38.. Washington, DC: CALDER, Urban Institute. [ Links ]

Clotfelter, C., Ladd, H. & Vigdor, J. 2010. Teacher Credentials and Student Achievement in High School: A Cross-Subject Analysis with Student Fixed Effects. Journal of Human Resources, 45(3):655-681. [ Links ]

Clotfelter, C.T., Ladd, H.F., Vigdor, J.L. & Wheeler, J. 2007. High-poverty schools and the distribution of teachers and principals. North Carolina Law Review, 85:1345-1379. [ Links ]

Coelli, M. & Green, D. 2012. Leadership Effects: School Principals and Student Outcomes. Economics of Education Review, 31(1):92-109. [ Links ]

Eberts, R. & Stone, J. 1988. Student Achievement in Public Schools: Do Principals Make a Difference? Economics of Education Review, 7(3):291-299. [ Links ]

Elmore, R.F. 2000. Building a New Structure for School Leadership, Washington DC: The Albert Shanker Institute. [ Links ]

ELRC (Education Labour Relations Council). 2003. Collective Agreement 8 of 2003. Integrated Quality Management Systemi. Pretoria: Education Labour Relations Council. [ Links ]

Gates, S., Ringel, J., Santibanez, L., Guarino, C., Ghosh-Dastidar, B. & Brown, A. 2006. Mobility and turnover among school principals. Economics of Education Review, 25:289-302. [ Links ]

Grissom, J., Kalogrides, D. & Loeb, S. 2012. Using Student Test Scores to Measure Principal Performance. NBER Working Paper Series No 18568. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. [ Links ]

Gustafsson, M. & Taylor, S. 2013. Treating schools to a new administration. The impact of South Africa's 2005 provincial boundary changes on school performance. Stellenbosch Working Paper Series No WP28/2013. Stellenbosch: Department of Economics, Stellenbosch University. [ Links ]

Gustafsson, M. 2009. Teacher Supply Patterns in the Payroll Data. Unpublished report produced for the Department of Basic Education.

Hallinger, P. & Heck, R. 1996. The Principal's Role in School Effectiveness: An Assessment of Methodological Progress, 1980-1995. In: K. Leithwood (Ed.). The International Handbook of Research on Educational Leadership and Administration. New York: Kluwer Press. [ Links ]

Hanushek, E. & Woesmann, L. 2007. The Role of School Improvement in Economic Development. NBER Working Paper Series No 12832. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. [ Links ]

Hanushek, E. 2007. The Single Salary Schedule and Other Issues of Teacher Pay. Peabody Journal of Education, 82(4):574-586. [ Links ]

Hanushek, E., Kain, J. & Rivkin, S. 2001. Why Public Schools Lose Teachers. NBER Working Paper Series No 8599. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. [ Links ]

Heystek, J. 2015. Principals' perceptions of the motivation potential of performance agreements in underperforming schools. South African Journal of Education, 35(2):1-10. [ Links ]

Hoadley, U. & Ward, C. 2009. Managing To Learn: Instructional Leadership in South African Schools. Teacher Education in South Africa Series. Cape Town: Human Sciences Research Council. [ Links ]

John, V. 2012. Improved Annual National Assessment results impossible, say academics. Mail and Guardian, 7 December. Retrieved from http://mg.co.za/article/2012-12-07-improved-annual-national-assessment-results-impossible-say-academics (accessed 25 June 2015).

Khumalo, G. 2011. Mixed feelings on principals' performance contracts. South African Government News Agency, 29 June. Retrieved from http://www.sanews.gov.za/south-africa/mixed-feelings-principals-performance-contracts (accessed 26 June 2015).

Leithwood, K., Louis, K., Anderson, S. & Wahlstrom, K. 2004. Learning from Leadership Project: Review of Research - How Leadership Influences Student Learning. Ontario: Center for Applied Research and Educational Improvement, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education. [ Links ]

Loeb, S., Kalogrides, D. & Horng, E. 2010. Principal preferences and the unequal distribution of principals across schools. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 32(June):205-229. [ Links ]

Miller, A. 2013. Principal turnover and student achievement. Economics of Education Review, 36:60-72. [ Links ]

NPC (National Planning Commission). 2012. National Development Plan 2030: Our future - make it work. Pretoria: National Planning Commission. [ Links ]

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2014. Chapter 3: The Importance of School Leadership. In: TALIS 2013 Results: An International Perspective on Teaching and Learning, TALIS. Paris: OECD Publishing. [ Links ]

PGWC (Provincial Government of the Western Cape). 2015. Regulations on the issuing of performance indicators binding on public schools. Provincial Gazette Extraordinary 7399. Cape Town: PGWC. [ Links ]

Phakathi, B. 2012. Minister wants principals' performance contracts this year. Business Day Live, 8 August. Retrieved from http://www.bdlive.co.za/articles/2012/03/13/minister-wants-principals-performance-contracts-this-year;jsessionid=A56104C4F14221BA855F55AE5BFA5919.present2.bdfm (accessed 26 June 2015).

Pillay, S., De Beer, M. & Duffy, K. 2012. Evaluating and managing employee turnover using benchmarks: A study of national government departments based on organisational size. Fourth International Conference on Establishment Surveys, June 11-14, Madrid, Spain.

Pont, B., Nusche, D. & Moorman, H. 2008. Improving School Leadership. Volume 1: Policy and Practice. Paris: OECD Publising. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/education/school/44374889.pdf (accessed 11 May 2015).

Pritchett, L. 2013. The Rebirth of Education - Schooling Ain't Learning. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development. [ Links ]

Robinson, V., Lloyd, C. & Rowe, K. 2008. The Impact of Leadership on Student Outcomes: An Analysis of the Differential Effects of Leadership Types. Education Administration Quarterly, 44(5):635-674. [ Links ]

RSA (Republic of South Africa). 2007. Education Laws Amendment Act No. 31 of 2007. Government Gazette, Vol 510, No 30637, 31 December 2007. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

RSA DBE (Republic of South Africa. Department of Basic Education). 2012. IQMS Annual Report 2011/12. Pretoria: Department of Basic Education. [ Links ]

RSA DBE. 2014a. Second Detailed Indicator Report for the Basic Education Sector. Pretoria: Department of Basic Education. Retrieved from http://www.education.gov.za/researchreports/tabid/708/Default.aspx (accessed 23 June 2015).

RSA DBE. 2014b. The South African Standard for Principalship. Government Gazette, No. 37897, Notice 636 of 2014, 7 August 2014. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

RSA DBE. 2014c. Vote No. 15 Annual Report 2013/14. Pretoria: Department of Basic Education. [ Links ]

RSA DBE. 2015a. Action Plan to 2019: Towards the realisation of schooling 2030. Pretoria: Department of Basic Education. [ Links ]

RSA DBE. 2015b. Annual Performance Plan for 2015-2016. Pretoria: Department of Basic Education. [ Links ]

RSA DoE (Republic of South Africa. Department of Education). 2003. Personnel Administrative Measures (PAMS). Government Gazette, No. 24948, 21 February 2003. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

RSA. 2015. Western Cape Education Expands Competency Based Assessments. Media statement, 21 April 2015. Retrieved from http://www.gov.za/speeches/western-cape-education-department-wced-expand-competency-based-assessments-appointment (accessed 30 April 2015).

Smit, L. 2013. Wanted: Accountable Principals. Helen Suzman Foundation. Retrieved from http://hsf.org.za/resource-centre/focus/focus-68/(9)%20Louise%20Smith.pdf/view (accessed 24 June 2015).

Taylor, N. 2012. NEEDU National Report 2012: The State of Literacy Learning and Teaching in the Foundation Phase. Pretoria: National Education Evaluation and Development Unit (NEEDU). [ Links ]

Taylor, N. 2014. NEEDU National Report 2013: Teaching and Learning in Rural Primary Schools. Pretoria: National Education Evaluation and Development Unit (NEEDU). [ Links ]

Taylor, N., Gamble, J., Spies, M. & Garisch, C. 2012. Chapter 4: School Leadership and Management. In: N. Taylor, S. van der Berg & T. Mabogoane (Eds.). What Makes Schools Effective? Report of South Africa's National School Effectiveness Study. Cape Town: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Taylor, S. 2011. Uncovering indicators of effective school management in South Africa using the National Schools Effectiveness Study. Stellenbosch Working Paper Series No WP10/2011. Stellenbosch: Department of Economics, Stellenbosch University. [ Links ]

Van Onselen, G. 2012. How Sadtu and the SACE have damaged accountability in SA education. Retrieved from http://inside-politics.org/2012/06/25/how-sadtu-and-the-sace-have-damaged-accountability-in-sa-education/ (accessed 24 June 2013).

Weinstein, J., Munoz, G. & Raczynski, D. 2011. Chapter 18: School Leadership in Chile: Breaking the Inertia. In: T. Townsend & MacBeath, J. (Eds.). International Handbook of Leadership for Learning. New York: Springer. [ Links ]

Welch, T. 2009. Teacher Education Qualifications: Contribution by Tessa Welch to a working paper for the Teacher Development Summit, 29 June to 2 July 2009. Unpublished manuscript.

Wills, G. 2015a. A profile of the labour market for school principals in South Africa: Evidence to inform policy. Stellenbosch Working Paper Series No WP 12/2015. Stellenbosch: Department of Economics, Stellenbosch University. [ Links ]

Wills, G. 2015b. Integrating administrative datasets in education: The case of educator payroll data and national schools data. Unpublished paper.

Wills, G. 2015c. Investigating the consequences of principal leadership changes for school performance in South Africa. Paper presented at the 2015 MASA conference, Salt Rock, South Africa. [ Links ]

Witziers, B., Bosker, R. & Kruger, M. 2003. Educational leadership and student achievement: The elusive search for an association. Educational Administration Quarterly, 39(3):398-425. [ Links ]

* Email address: gabriellewills@gmail.com

1 The little we know about the practices of school leaders and managers and how their actions influence learning has been informed through a few case studies of schools, particularly exceptional schools that have achieved excellent academic results despite facing various school constraints. Christie, Butler and Potterton (2007) for example conducted case studies of 18 schools that achieved good to excellent results in the matric certificate. Their research concluded that effective leadership was a critical success factor explaining student achievement across these schools. There is also some suggestive evidence of the importance of school management more broadly for learning in schools (Taylor 2011; Taylor, Gamble, Spies & Garisch 2012.)

2 Access to Persal data was obtained through the Department of Basic Education in order to assess the degree to which different datasets could be merged with a view to monitoring the movement of staff across schools over time. Assistance from Martin Gustafsson at the Department of Basic Education in understanding the data is acknowledged. Snap data has recently been made publically available to researchers through the DataFirst Portal. Access to other non-public datasets was obtained through participation in a research project conducted for The Presidency and titled 'Programme to Support Pro-poor Policy Development' (PSPPD).

3 Mandatory retirement age for educators in South Africa is 65 years. However, where pensions are accessible at earlier ages the majority of teachers retire well before 65 years.

4 The Personnel Administrative Measures identify the minimum qualification criteria for a permanent entry level teacher appointment as REQV level thirteen (RSA DoE 2003). In practice, however, this has increased to REQV fourteen where teachers should possess a four-year bachelor degree in teaching or a three-year degree in another subject area and one additional year specialising in education.

5 It is entirely possible that years of service as a principal specifically, may provide a more useful indicator of a principal's capacity to execute his or her leadership function - principal experience may matter more than just teaching experience. But it was not possible to distinguish between years in a principal post from overall teaching experience in the public education sector with the data available. This is a limitation of the analysis.

6 Martin Gustafsson's report produced for the Department of Basic Education in 2009 entitled 'Teacher supply patterns in the payroll data', identifies six % year-on-year attrition for educators in South Africa. However he finds that attrition is halved if you exclude 'churners' being those that exit then return to public education. It is important to note that depending on the definition of attrition used and the data years considered in calculations, rates of attrition may vary considerably. Multiple years of data are required to fully account for multiple entries and exits of individuals (Gustafson 2009). The turnover rates that have been calculated in this paper for principals and other educators only calculate turnover between two points of data. Churning may occur between these data points.