Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Childhood Education

On-line version ISSN 2223-7682

Print version ISSN 2223-7674

SAJCE vol.4 n.3 Johannesburg 2014

ARTICLES

A research base for teaching in primary school: A coherent scholarly focus on the object of learning

Ruksana Osman*; Shirley Booth

University of the Witwatersrand

ABSTRACT

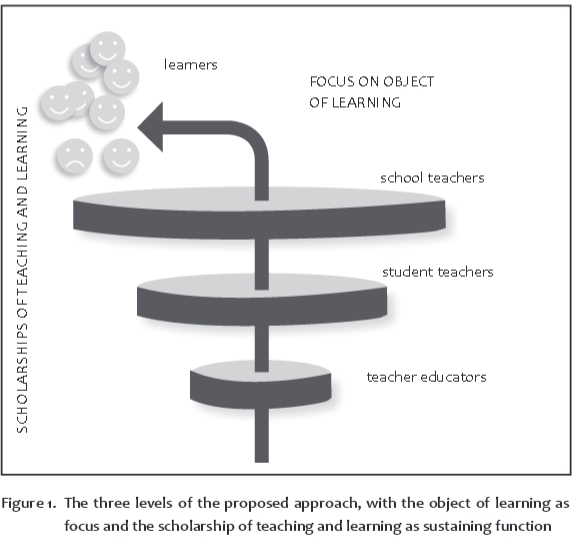

This paper makes a case for a new impetus in creating a coherent research basis for childhood education and teacher education in South Africa. We are proposing a three-level - teacher educators, student teachers and practising teachers - research-led approach that integrates teacher education, schooling and early learning. The aim of the approach is to enhance the quality of learning in primary schools through systematic focus on the object of learning, whether in terms of teaching in school or educating entrants to the teaching profession at the university, or teacher educators inquiring into their practice. There are two thrusts involved: on the one hand bringing the focus of teachers, teaching students and teacher educators coherently onto the object of learning and thereby bringing it to the attention of their respective learners, and on the other hand invoking the principles of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL) movement, thereby enabling its sustainability. We illustrate our case with two examples from the literature that show clearly how learning in school can be enhanced when teachers are actively studying what and how their learners are learning in connection with their teaching and where the work is disseminated in a scholarly manner.

Keywords: Childhood learning, childhood education, teacher education, object of learning, scholarship of teaching and learning, South Africa, variation theory

Introduction

The central argument of this paper is that there is a need for a new impetus to create a coherent research basis for childhood teaching and teacher education in South Africa. Researchersin this sector, although having recently established a scholarly organisation, the South African Association for Research in early Childhood Education (SARAECE), are only in their first five years of working together. As is the case with other educational sectors, the 'apartness' motive of the apartheid regime also kept researchers apart. We would argue that South African education (with its researchers) is still, more than twenty years after the change of regime, in a period of transformation from a historically divided system. In this system, some received the finest available education and others received minimal training for what was considered suitable employment (Sedibe 1998). There are still multiple threads of improvement called for in the schooling system, from preschool to higher education. A recent report on the state of schooling in the first three grades shows compellingly that the system is underperforming across nine provinces in South Africa (Taylor 2012), and areas of great weakness in literacy teaching and learning in the early years of schooling still persist (Nel 2011). The school system is intended to move towards an equitable curriculum, where critical understanding and lifelong learning are two of the key concepts. This means, in turn, a change in curriculum for pre-service teacher education as well as a long-term programme of in-service development, and that curriculum, education and development for teaching need to be put on a firm research base. Here we are outlining a new impetus for such a research base, at three levels of the education system, and with two research thrusts. The underlying thinking is that in order to achieve the above, there needs to be research; furthermore, this research must be coherent and able to look at education practice from various positions within the practice of education.

For such thinking, one has to explore some of the ways in which theories of teaching were utilised during the apartheid era, and also what teacher educators expressed about their knowledge of children's learning. As one policy maker, Sigamoney Naicker wrote:

(E)ducation departments and teacher training institutions in South Africa adopted or developed theories of learning that supported this idea that teachers should be controllers in the classroom [...] Teaching was seen as providing, in the classroom, well-established facts, exercises and mental drills which would get these [innate] ideas going. Knowledge came to be seen as fixed, innately known, and learning involved its repetition in order to get it out and get it going (Naicker 2006:3).

This rather general description by Naicker may refer to schools that he had investigated and leaves some questions unanswered; for example, if knowledge is "innately known", does this mean that it was present at birth? Teachers in the majority of primary schools were not educated and trained to teach inquiry and to work conceptually. Many teachers still work in this way, despite a curriculum that requires conceptual learning and inquiry.

When Curriculum 2005 was introduced in 1996, it "was described as a single curriculum that was learner-paced, learner-based and of an inclusive nature", and when the curriculum was once again revised in 2002, it highlighted the principles of "inclusion, human rights, a healthy environment and social justice" (Naicker 2006:4). However, although separate schooling has been abandoned altogether, it has left a legacy of problems. Evidence suggests that the range of educational opportunities offered to children still differs widely depending on the locality, history, teacher competence and leadership in the schools they attend (Fleisch 2008). In general terms, rural schools are less well equipped than urban schools; schools that were formerly intended for white children have better resources than many others; private schools have better qualified teachers than many state schools (where teachers without qualifications are not unknown); and the culture of teaching and learning has had to be reinstated in schools that, not too long ago, were characterised more by their political opposition to apartheid than a dedication to teaching and learning (Christie 1998).

In recent times the media has focused sharply on failing school learners, poor foundations in early education, dysfunctional schools, and the downfall of outcomes-based education in South Africa (Bergman & Bergman 2011). Implicitly, the media focus has also been on ineffective teacher preparation, raising questions about quality teacher training for childhood education, the most efficient pathway for teacher preparation, the ideal location for such teacher preparation programmes (universities, colleges of education or teaching schools), and issues of teacher identity and teachers' work.

This scrutiny is not going to go away; if anything, it will become sharper and harsher during the next few years, as market driven demands for accountability and efficiencies in teacher education become the order of the day. Educational quality will be judged based on the extent to which institutions comply with state policies and programmes on the extent to which the state is getting value for money invested in education. This state of affairs needs to be turned around; confidence and trust in teacher education needs to be rebuilt, as teacher education has many stakeholders: parents, whose young children are going to be educated by these teachers; the department of education that funds the teachers in their studies; and the universities where schools of education are located. There may be many approaches one could take to rebuild the academic project of schooling and teacher education; the one that is proposed in this article is to bring a focused scholarship to teaching and teacher education. If early schooling and teaching are to change and reform, then teacher education must show similar change and reform (Cochran-Smith & Lytle 1993; Reis-Jorge 2005). This link between early schooling and reform in teacher education, and in society more broadly, has also been confirmed in a study undertaken by Petersen and Petker (2011).

Teacher education, currently located in universities and recognised as an academic education, rather than the 'training' associated with the former teacher training colleges, has the task of wiping out educational injustices and providing the country and its children with a school system that is accessible, fair and committed to a transformed culture of learning and teaching.

The Bachelor of Education programme, a four-year programme for whichever stage of schooling the student teacher is focusing on, is governed throughout South Africa by a comprehensive set of norms and standards laid down by central government. In 2000, the then Minister of Education, Kader Asmal, issued the 'Norms and Standards for Educators' (RSA DoE 2000), which were also indirectly aimed at programmes of teacher education. The policy defined seven roles that an educator must be able to perform and described in detail the knowledge, skills and values that are necessary to perform these roles successfully. The roles were those of learning mediator; interpreter and designer of learning programmes; leader, administrator and manager; scholar, researcher and lifelong learner; assessor; a community, citizenship and pastoral role; and a learning area/subject/discipline/phase specialist role. The main criticisms levelled against the Asmal policy were that it was not possible to expect all teachers to be able to play all these roles and that the roles were not hierarchically ordered, so that, for example, the pastoral and administrative roles were put on the same level as those of assessor and discipline specialist. The policy was subsequently extended and elaborated in the 'Minimum Requirements for Teacher Education Qualification' policy document (RSA DHET 2011), which focuses more sharply on disciplinary knowledge and foregrounds its importance for classroom teaching and learning. This is an important feature of our emphasis on focused scholarship in teacher education.

There is now an expectation that future teachers will need to be prepared in a way that will enable them to respond to the learning needs of learners and to decide which pedagogies are best suited for this purpose, as well as to prepare learners to participate effectively as fully fledged citizens of a country that is attempting to transform itself in all spheres of life. These different layers of demands on teachers place a responsibility on teacher educators to ensure that teacher education programmes resonate with the problematic of the practitioner and that they produce teachers who can teach in all schools in the country, not just elite schools reserved for the privileged few. The different layers of demand place teachers' disciplinary knowledge, or knowledge of school subject matter, as central to transforming teacher education and schooling at all levels, starting from childhood.

Although the shift in policy foregrounds teachers and teachers' knowledge, it does so without considering the connection between teachers and teacher education (Du Plooy & Zilindile 2014). How this is interpreted (Rousseau 2014) and implemented (Du Plooy & Zilindile 2014) remains unclear.

In this paper we are proposing a three-level - teacher educators, student teachers, practising teachers - research-led approach to relevant aspects of the education system that can ameliorate some, though by no means all, of the shortcomings in primary school through measures that integrate teacher education, schooling and early learning. The aim of the approach is to enhance the quality of learning in primary schools through systematic focus on the object of learning, whether in teaching in the schools, educating entrants to the teaching profession at the university, or conducting research on teacher education at the university. There are two thrusts involved in the approach: bringing the focus of teachers, teaching students and teacher educators coherently onto the object of learning and thereby bringing it to the attention of their respective learners; and invoking the principles of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL) movement, thereby enabling its sustainability. We will offer two examples below which can be interpreted in terms of our proposed focus on objects of learning for primary education.

Focus on the object of learning: what it signifies and how it can be sustained

Morrow (1994) identified epistemological access as an obstacle to success in schooling and higher education, and we make the point here that such access is essential for long-term success even in the earliest years of schooling and education, but has hitherto been largely underdeveloped in South Africa. A shift from epistemological access as a political issue related to the democratisation of access to higher education (ibid) to a learning issue related to access to the early foundations of learning is necessary (Du Plooy & Zilindile 2014). The latter authors call for "less research philosophising about what is needed to achieve success in schools and more research into how this could be made possible" (ibid:198-i99).

This is where the first thrust of our proposal for a three-level research-led approach to primary education comes into play. The object of learning is a construct which has emerged from a body of research that has been developed over the past ten years or so. It is grounded in phenomenography and variation theory of learning (Marton & Booth 1997; Marton & Tsui 2004), and the learning studies, where these have been applied to classroom teaching and learning (Pang 2006; Pang & Marton 2005). These authors argue that throughout an educational system, teachers have objectives, whether articulated or not; they know what they want the learners to learn and they know how it is to be assessed. But the object of learning differs somewhat from these objectives, in that it is not only seen in the single dimension of what to teach and what to assess, but also in the many dimensions of what is intended to be learned, how is it enacted in the classroom, and how it is experienced by learners during the class and lived by them afterwards1. Thus it raises the question not only of what learners are to learn, but also how they relate to what they have learned. Ming Fai Pang, a scholar in the field, differentiates between teachers' learning objectives and the object of learning as follows:

The main difference between our concept of the object of learning and the far more common concept of learning objective is that whereas the latter refers to the goal, target, or aim of learning, the former also refers to the conditions and the outcome of learning. The idea is to describe goal, conditions, and results in commensurable terms (Pang 2006:41).

But more importantly for the purpose of this paper, a number of empirical questions arise, offering a framework for inquiry into classroom practices and outcomes that focus on the object of learning: What is it that is intended to be learned? What approaches to enacting these intentions are to be found in the classroom? How are the learners experiencing what is being learnt? And what effects are to be seen in the longer term? Each of these four questions lend themselves to study with a phenomenographically inspired approach, where qualitatively different ways of experiencing the phenomenon (what is intended, how it is enacted, how it is experienced, and how it is lived) can be revealed (Bowden & Walsh 2000).2

This first thrust to our proposal, then, involves teacher educators, student teachers and practising teachers focusing on the object of learning, asintended, enacted, experienced and lived. Much of the work with such a focus has been carried out in the form of learning studies, a form of lesson study, where variation theory provides the conceptual framework for design through consideration of critical features and a commensurate analysis of outcomes, all carried out by teams of teachers with a common interest and goal (Elliott 2012). Pang explains learning study as follows:

Above all, the learning study is a systematic attempt to improve teaching and learning which combines theory and practice, and which focuses primarily on the objects of learning as well as the professional collaboration of teachers. It can be used for research, for teacher education and for teachers' professional development in a school. The learning study provides opportunities to improve student learning, as well as for teachers to enhance their professional learning (Pang 2006:41).

While the intended object of learning will come directly from the planned curriculum and the teacher's knowledge of it, its enactment will reflect the teacher's understanding of her learners and of appropriate pedagogy. In order to reveal the learners' experienced and lived object of learning, an inquiry needs to be made, capturing the ways in which the object has been grasped by generating, collecting and analysing appropriate data. On the one hand this can lead to the development of teaching that particular object of learning by that particular teacher, and on the other, to a shared understanding of teaching it among teachers working in teams.

Two studies focusing on clear objects of learning for primary education

We illustrate the first thrust of research-led approaches to primary education with two examples taken from different parts of the overall education system - one from South Africa and one from Sweden - where we can clearly identify an object of learning which has been investigated with the purpose of developing pedagogy with a clear content focus. We have chosen one object of learning that is value-laden rather than cognitive, and one that typifies fundamental learning in the primary school.

The first example is from a first-year pre-service programme in teacher education, where the object of learning was food security, tackled within a broader agenda of equity and social justice as it affects education. Petersen (2014) introduced this object of learning by means of a simulation game during a week-long excursion with culturally diverse South African students. As an intended object, it was enacted by having the students role-play one of three roles, namely members of a small minority of well-resourced individuals, a larger minority of medium-resourced individuals, and a large majority of under-resourced individuals, based on set amounts of 'play' money allocated to each student. Food was made available, but came with a price tag attached to each item, so that the well-resourced could enjoy a full plate while the under-resourced could afford, maybe, a cracker or piece of bread; in other words, they could have what they could pay for. As the students were isolated and dependent on the camp organisers for food and shelter, the exercise had a degree of authenticity. The respective groups were then given the opportunity to discuss and report on the feelings they experienced as they contemplated the plates of others. Petersen explains that the experienced object of learning was to be found in "such words as 'hopeless', 'desperate', 'sadness', 'humiliated', 'ashamed', 'deprived', 'frustration', 'excluded', and 'devalued'", which students used "to describe their feelings about the situation". Among the poorly resourced, statements included: "We banded together to survive; it empowered us, but even when we put our money together it was still not enough to buy anything from the table. Those with money had taken it all"; and "We felt justified in resorting to stealing from those who have more" (ibid:9-10).

The long-term object of the exercise was to make these future teachers more aware of learners' varied situations, in particular the effects of poor nutrition. Reflective diaries kept by the students give evidence of such forward-looking learning, for example, "I have begun to realise the impact of a lack of resources on children and their ability to learn"; and "I have a constant awareness of how various factors intersect in children's lives and what this means for the teacher's job. It directly affects the teacher's level of care and accountability" (Petersen 2014:10).

The important things to note here are (a) the topic of food security was an ongoing focus for the teacher educator's commitment to social justice and equity; (b) the enactment of a simulation game brought new and alternative perspectives to the issue and to the participating students; and (c) that the student teachers were encouraged, and able, to offer ways in which the topic would influence their own perspectives on food security and nutrition in future. The intended, the enacted, the experienced and the lived object of learning are all seen here.

The above is an example of a teacher educator bringing a specific object of learning to the attention of her students, with the longer term purpose that her students, when practising teachers, will pay attention to issues of social justice in their classrooms and in the lives of their learners. The second example we offer involves a Swedish teacher educator and a group of six experienced primary school teachers designing and executing lessons with a focus on plant growth for children aged seven to twelve years in mixed age groups (Wikström 2008).

The teachers had previously studied biology with the same teacher educator in order to teach it as part of the Swedish lower secondary school curriculum. The goal, for this age group, was to be "able to give examples of the life cycle of some plants and their growth processes" (Wikström 2008). In preparation for teaching the topic, the teacher educator and teachers met three times to establish what the object of learning should be if special attention was to be drawn to photosynthesis and cellular respiration: "What does 'being able to give examples' really mean? How can that goal in the biology syllabus be interpreted?" They "agreed that it could involve being able to answer such questions as: What is a seed? How is the seed formed? What is inside a seed? What happens when the seed germinates and the plant grows and reproduces again?" There was an understanding that the subject was complex and that different answers would be given, especially considering the age range of the pupils. However, it was agreed that all the pupils should understand that "during the right environmental conditions, cellular respiration is (a) going on inside the seed when it germinates; (b) that it is a combustion process that demands fuel and oxygen; and (c) that this process provides the seed with energy for different kinds of work" (ibid:216-217).

After these planning sessions the teachers were left to conduct their teaching over a number of lessons in whichever ways they believed appropriate for their classes; there was no expectation that they would enact the object of learning in the same ways, but it was expected that the intended object would be strongly in focus in their teaching. The aim of the teacher educator was to study what the teachers did - in what ways they enacted the object of learning - and what the pupils were able to learn. The first two lessons were observed, and the final one - in which the teachers had been told to summarise the whole teaching sequence - was video recorded and a number of pupils from the different classes were interviewed.

In the study in question, the teacher educator's first task was to analyse what had happened during the lessons that had the potential to bring critical features to the attention of the pupils; in other words, what spaces of learning had been created. The second task was to analyse the interviews to see what the pupils had experienced, that is, what they had learned from the lessons. The third task was to relate the pupils' learning to the teachers' teaching in collaboration with the teachers, who acted as informants and critical validators.

The outcome of the study as research is not central to the interest of this paper; however (a) the way in which the object of learning was discussed and agreed upon; (b) the fact that the different teachers brought different aspects to the fore in their teaching, thereby creating different potential spaces for learning among their pupils; and (c) the fact that the teachers were able to learn more about handling this object of learning by collaborating in analytical procedures are to be noted.

Scholarship of Teaching and Learning for sustainability

We are only able to show the two examples above because they have been framed as research studies, generating relevant data and analysing them in various ways. Above all, the work was shared with the global community of teacher educators like ourselves and our readers, and in the case of Wikström (2008), also shared with the community of teachers. The first example points to studies based in higher education, specifically teacher education, while the second points to a study based on school teaching. Both involved generation of data through surveys, observations and interviews. The examples described above bring objects of learning into focus at different levels of the educational system. Petersen (2014), a teacher educator, focused on social justice and the issues of equity and food security with her student teachers, in the process not only bringing them to a greater understanding of their future pupils' life situations, but also equipping them to better teach related issues when they eventually stand in front of a classroom. Wikström, also a teacher educator, brought a specific object of learning to the attention of practising teachers who, in turn, taught their classes with that object in focus, though in different ways. Through their scholarly participation in the study, these teachers had the opportunity to discern improvement for their future teaching of that object.

We now have a picture of focused scholarship in primary education. We see teacher educators interacting with their students (whether student teachers or experienced teachers) and associated school teachers (whether Petersen's student teachers in their future practice or Wikström's teachers in their classrooms) taking part in different kinds of studies in the context of their teaching, and this taking place in two different demographic and educational contexts.

Educational research in general is often characterised (and criticised) as being diffuse and small-scale; for not building a body of coherent knowledge that can be shared and disseminated (Deacon, Osman & Buchler 2010). Our picture thus far does nothing to counter such criticism, albeit that we propose a common focus for study. Stenhouse (1981:113) described educational research as:

[...] systematic and sustained inquiry, planned and self-critical, which is subjected to public criticism and to empirical tests where these are appropriate. Where empirical tests are not appropriate, critical discourse will appeal to judgment of evidence - the text, the document, the observation, the record. In applied or action research the test or evidence may be provided by substantive action, that is, action which must be justified in other than research terms.

Building on this view of research, our research-led approach has a second thrust, which is intended to ameliorate the fragmentation that is not only the object of criticism, but also leaves the practising teacher and even the teacher educator without a coherent research base for professional development. The movement that has come to be known as the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL) is generally acknowledged to have originated in the work of Ernest Boyer of the Carnegie Foundation (Boyer 1990). In an attempt to raise the status of teaching at institutions of higher education, where research is more highly prized, he identified four domains of scholarship, namely discovery, integration, application and teaching. The fourth of these - more commonly known today as the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning to emphasise the purpose of teaching - has grown into a multifaceted movement with international journals and conferences where academics from all disciplines meet to disseminate their scholarly work in, and thoughts on, their profession as teachers.

The major principles underpinning SoTL in higher education in general are that the academic investigates his or her own practices of teaching and/or the students' practices of learning; that the outcomes of such investigation are open for inspection and validation by colleagues; and that they are disseminated either locally or globally (Ashwin & Trigwell 2004) - or, Stenhouse (1981:113) might have added, "provided by substantive action". In our conceptualisation of a research-led approach to childhood education with scholarship focusing on the object of learning we see the potential for sustainability and for the building of a coherent body of knowledge that is relevant to classroom learning.

One area of the academy that one might expect to be well represented in the SoTL community is that of teacher education, but it seems to be outnumbered by the natural and applied sciences. The disciplines of academic, educational or pedagogical development in institutions of higher education are dominant in the field, but the voices of teacher educators at school level are rarely heard. On the other hand, teacher educators have a rich access to theory and research on learning and teaching as well as other aspects of education and society which are generally not readily available to academics in other disciplines. This suggests that teacher educators should be supported in investigating their own and their students' learning and teaching and encouraged to engage teachers in the work. The opportunities are many, and the potential rewards are great. Apart from being teachers in their own right, in the university, teacher educators also have direct access to schools while supervising their students' professional teaching experience sessions. Without doubt, both of these opportunities give rise to scholarly activity, but it is rare that they are studied rigorously, problematised, questioned, collected, collated and analysed to form the basis for such rigorous study, or shared with those outside the immediate circle of close colleagues. The rewards can come at the level of enhanced insight into student teachers' knowledge, skills and understanding of their chosen profession.

Discussion

Sustaining change for learning

While the SoTL movement focuses mainly on the 'S' and the T, our two examples - and our research-led approach - foregrounds the 'L', learning. The examples show clearly how learning in school can be enhanced when teachers are actively studying what and how their learners' are learning in connection with their teaching, whether they have become habituated through their own teacher education, or whether in collaboration with ongoing school experience. Learning in the teacher education programmes can be enhanced when teacher educators focus on the object of learning and actively pursue studies of their own students' learning in the schools of education. Focus on the object of learning to the extent of carrying out learning studies collaboratively and iteratively has been found to enhance pupils' learning even after the learning studies have been completed. This so-called generative learning has been described in the literature for learning English as a second language, Swedish literacy (first language), and telling the time in the Swedish primary school (Holmqvist, Gustavsson & Wernberg 2007), where it is reported that there was a significant improvement in a delayed test compared to a post-lesson test.

Figure 1 shows our proposed research-led approach to primary education, where SoTL - complete with 'S', 'T' and 'L' - can be characterised as having transformative potential at three levels: at the individual, the institutional and the societal levels. All three levels of the education system are open to such transformation, as illustrated to a first order in Figure 1. At the individual level there will be teachers and teacher educators who are learning about their professional practices, potentially transforming those practices. At the institutional level we have, on the one hand, the school, where teachers are able to discuss and collaborate in a more reflective mode on their learners' experiences in the classroom, and on the other, the university schools of education where staff will be contributing to their professional body of knowledge. And at a societal level, in the long run, there will be an enhanced quality of learning in the schools. This is where SoTL fulfils a sustaining function, through gradual and coherent transformation at these three levels.

Theory and practice bridged for professional development

Our approach has a direct bearing on the perennial debate about the relation between theory and practice in both teacher education and school teaching. There is a tradition of seeing teaching in the early years of schooling as a craft or skill, and teacher education (or 'teacher training') as preparation for such teaching, with an emphasis on method. When the shortcomings in such an approach to teaching are revealed -for example, the difficulties experienced by teachers with the 'skill' mindset when it comes to introducing new curricula or considering new approaches to teaching -there is a polar shift to an emphasis on theory in teacher education, so that teaching becomes regarded as needing the application of theory from what are viewed as the foundational disciplines of sociology, psychology and philosophy, and teacher education is subsumed under those disciplines. Such a seesaw has characterised teacher education in South Africa: the colleges of education with a skill bias were closed in favour of university-based schools of education with a theoretical bias.

There is a worrying trend in the education systems and schools of many countries, including South Africa, to reduce teacher autonomy and to de-professionalise teaching by, for example, expecting teachers to deliver scripted lessons without necessarily engaging with the knowledge their pupils need to engage with. This reduces the learners' position to that of receptacles of given, unproblematised, bodies of knowledge. Bringing focus to objects of knowledge, designing lessons, and inquiring into learning outcomes by means of the approach that we are promoting here suggests a different role for the teacher. It allows teachers to imagine a progressive social vision that could deepen their understanding of teaching in environments characterised by inequality and which are distinct and distant from the university classroom. More importantly, this orientation to their education could bring teachers closer to research and scholarship, rather than isolating them from it, as is the case traditionally.

We envisage development of teachers and teacher educators where their practices in relation to the objects of learning are the focus of ongoing study. Teacher educators could be engaged in studies where they are not looking in the first place to theories from the foundational disciplines, but to the issues of teaching and teacher education themselves. Others might investigate their own practices, again within the context of teacher education focusing on classroom practices, or work with their students to study issues arising from their teacher education. Thus a community of learning would be built in which teachers, student teachers and teacher educators work together to, on the one hand, build a knowledge base for teacher education where theory and practice are integrated with focus on the objects of learning and, on the other hand, offer future teachers a grounding in scholarship for their own future professional development.

Conclusion

We have been making a case for a new impetus in creating a coherent research basis for childhood education and teacher education in South Africa: a three-level research-led approach that integrates teacher education, schooling and early learning. A systematic focus on the object of learning, whether in teaching in school, or educating entrants to the teaching profession at the university, or teacher educators inquiring into their practice, is one thrust of the approach. The principles of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL) movement, which holds inquiry as central, is proposed as a sustaining function. In this way we can arrive at what we would call 'learning classrooms' with 'learning teachers' at all layers of the system - from students to teachers to teacher educators - and 'learning pupils'. This process is incremental; it plays out over time. Most importantly, it is about teachers who bring the objects of learning to the fore in their teaching and their inquiry into teaching practice.

References

Ashwin, P. & Trigwell, K. 2004. Investigating staff and educational development. In D. Baume & P. Kahn (Eds.), Enhancing staff and educational development. London: Routledge Falmer. [ Links ]

Bergman, M.M. & Bergman, Z. 2011. Perspectives of learners and teachers on school dysfunction. Education as Change, 15(1):35-48. [ Links ]

Bowden, J. & Walsh, E. 2000. Phenomenography. Melbourne: RMIT University Press. [ Links ]

Boyer, E.L. 1990. Scholarship reconsidered: Priorities of the professoriate. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Christie, P. 1998. Schools as (Dis)organisations: The breakdown of the culture of learning and teaching in South African schools. Cambridge Journal of Education, 28(3):283-300. [ Links ]

Cochran-Smith, M. & Lytle, S. 1993. Inside outside: Teacher research and knowledge. New York: Teachers College Press. [ Links ]

Deacon, R., Osman, R. & Buchler, M. 2010. Scholarship in teacher education in South Africa: 1995-2006. Perspectives in Education, 28(3):1-12. [ Links ]

Du Plooy, L. & Zilindile, M. 2014. Problematising the concept of epistemological access with regard to foundation phase education towards quality schooling. South African Journal of Childhood Education, 4(1):187-201. [ Links ]

Elliott, J. 2012. Developing a science of teaching through lesson study. International Journal for Lesson and Learning Studies, 1(2):108-125. [ Links ]

Fleisch, B. 2008. Primary education in crisis: Why South African schoolchildren under achieve in reading and mathematics. Cape Town: Juta. [ Links ]

Holmqvist, M., Gustavsson, L. & Wernberg, A. 2007. Generative learning: Learning beyond the learning situation. Educational Action Research, 15(2):181-208. [ Links ]

Ling Lo M. 2012. Variation theory and the improvement of teaching and learning. Gothenburg: Acta Universitatis Gothobergensis. [ Links ]

Marton, F. & Booth, S. 1997. Learning and Awareness. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Marton, F. & Tsui, A.B.M. 2004. Classroom discourse and the space of learning. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Marton, F. 2014. Necessary conditions of learning. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

McCarthy, M. 2008. The scholarship of teaching and learning in higher education: An overview. In R. Murray (Ed.), The scholarship of teaching and learning in higher education. Berkshire, UK: McGraw-Hill. 6-15. [ Links ]

Meyer, J.H.F. & Land, R. 2005. Threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge (2): Epistemological considerations and a conceptual framework for teaching and learning. Higher Education, 49(3):373-388. [ Links ]

Morrow, W. 1994. Entitlement and achievement in education. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 13(1):33-47. [ Links ]

Naicker, S. 2006. From policy to practice: A South-African perspective on implementing inclusive education policy. International Journal of Whole Schooling, 3(1):1-6. [ Links ]

Nel, C. 2011. Classroom assessment of reading comprehension: How are pre-service foundation teachers being prepared? Per Linguam, 27(2):41-66. [ Links ]

Pang, M.F. & Marton, F. 2005. Learning theory as teaching resource: Enhancing students' understanding of economic concepts. Instructional Science, 33(2):159-191. [ Links ]

Pang, M.F. 2006. The use of learning study to enhance teacher professional learning in Hong Kong. Teaching Education, 17(1):27-42. [ Links ]

Petersen, N. & Petker, G. 2011. Foundation phase teaching as a career choice: Building the nation where it is needed. Education as Change, 15(1):40-61. [ Links ]

Petersen, N. 2014. Childhood education student teachers' responses to a simulation game on food security. South African Journal of Childhood Education, 4(1):1-16. [ Links ]

Reis-Jorge, J. 2005. Developing teachers' knowledge and skills as researchers: A conceptual framework. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 33:303-319. [ Links ]

Rousseau, N. 2014. Integrating different forms of knowledge in the teaching qualification Diploma in Grade R Teaching. South African Journal of Childhood Education, 4(1):167-186. [ Links ]

RSA DHET (Republic of South Africa. Department of Higher Education and Training). 2011. Minimum Requirements for Teacher Education Qualification. Government Gazette Vol. 553, No. 34467. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

RSA DoE (Republic of South Africa. Department of Education). 2000. Norms and Standards for Educators. Government Gazette Vol. 415, No. 20844. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Sedibe, K. 1998. Dismantling apartheid education: An overview of change. Cambridge Journal of Education, 28(3):269-281. [ Links ]

Stenhouse, L. 1981. What counts as research? British Journal of Educational Studies, 29(2):103-114. [ Links ]

Taylor, N. 2012. The state of literacy teaching and learning in the foundation phase. Pretoria: National Education Evaluation and Development Unit (NEEDU). [ Links ]

Wikström, A. 2008. What is intended, what is realized, and what is learned? Teaching and learning biology in the primary school classroom. Journal of Teacher Education, 19(3):211-233. [ Links ]

* Email address: Ruksana.osman@wits.ac.za

1. The current usage in research involving objects of learning refers only to the intended, enacted and lived object, and emphasises that all these are seen from the standpoint of the researcher. However, we introduce the experienced object of learning to make it possible to include the child's (or the student teacher's) immediate way of understanding the object as it is taught. In addition, we turn the concepts away from the exclusive domain of the researcher and make them accessible to the practising teacher.

2. There is more theoretical understanding of the constitution of an object of learning than we have hitherto touched upon, grounded in variation theory of learning and its empirical forerunner, phenomenography (Bowden & Walsh 2000). Phenomenographic research has shown that a given phenomenon can be understood (or experienced) in a small number of qualitatively distinct ways which can be hierarchically ordered in terms of complexity and completeness in relation to given goals, on a collective level (which is to say that the research does not seek to identify individual understanding or experience, but the qualitatively distinct ways in which the phenomenon can potentially be understood or experienced within the population of people of interest). What distinguishes one way of understanding from another is seen to be critical for moving from one understanding to another. Learning is then seen, simply put, as becoming able to distinguish such a critical feature which has the necessary (but not necessarily sufficient) key to opening a new way of understanding (or experiencing) the whole phenomenon. Learning becomes possible when one such critical feature is made invariant against a background of other features that are allowed to vary; a space for learning is created through the creation of certain patterns of variation (Marton 2014).