Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Childhood Education

On-line version ISSN 2223-7682

Print version ISSN 2223-7674

SAJCE vol.4 n.3 Johannesburg 2014

ARTICLES

'Learning walks': Dialogic spaces for integrating theory and practice in a renewed BEd foundation phase curriculum

Denise Zinn*; Deidre Geduld; Aletta Delport; Christina Jordaan

Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University

ABSTRACT

In teacher education, the integration of theory and practice is perhaps best manifested in work-integrated learning (WiL), which entails the merging of academic and professional knowledge domains (CHE 2011). The redesign of current BEd programmes at Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University (NMMU) to align with the Faculty of Education's new vision and mission started in 2011. Rigorous interrogation of previous and current paradigms and practices led to uncomfortable awareness of the lack of relevance of teacher preparation programmes in relation to conditions in the majority of schools in the country. Furthermore, the undesired schism between theory and practice was clearly exacerbated by the existing teaching practice model. The primary challenge was to design integrated, coherent new BEd programmes, to be responsive to the realities of the majority of South African schools, and to facilitate the connection between theory and practice in the teacher education programme. The study described in this article responded to this challenge through the application of a humanising curriculum framework that had been co-constructed within the Faculty. It led to the implementation of 'learning walks', the name given to the dialogic spaces which were created to develop and inform a new model of WiL.

Keywords: work-integrated learning, foundation phase, curriculum renewal, curriculum reform, post-apartheid South Africa, humanising curriculum framework, learning walks

Introduction

Learning to become a competent and proficient teacher is a complex matter encompassing more than mere acquisition of subject content knowledge. In addition, student teachers need to develop sound pedagogical content knowledge (Shulman 2004) and learn how to develop and work with curricula and learning programmes so as to "organise systematic learning" (Morrow 2007:51)63). They also need to acquire a deep understanding of the unique social, organisational and institutional contexts within which teaching and learning occur. Ultimately, they need to develop eloquent and conscious personal teaching philosophies and secure professional identities as committed, responsive, reflective and resilient future teachers (Morrow 2007; Shulman 2004).

Teacher education programmes are therefore normally designed to incorporate three distinct yet interrelated domains, namely subject matter (content); theories of teaching and learning (pedagogy); and professional experience (the practicum). Although there is general agreement that these domains are interdependent (Darling-Hammond 1999), integration within teacher education curriculum designs continues to be a challenge (Garm & Karlsen 2004; Lawrence & Palmer 2003). A particular challenge relates to the assimilation of the practicum component, which acknowledges that although academic disciplines constitute the knowledge base of the profession, for students to be truly successful in the workplace, the inclusion of meaningful, reflective practice in a real-life professional environment is not negotiable (Barnett 2006). In terms of teacher education, this means that particular attention needs to be paid to the quality of student teachers' classroom-based and school-based learning and to its assimilation into the general teacher education curriculum. With this objective in mind, the term 'work-integrated learning' (WiL) has recently been adopted in teacher education discourse in South Africa, referring in particular to an educational approach that integrates and aligns academic and workplace practices. Ultimately, the purpose is to enable student teachers to experience all dimensions of the workplace and reflect on their experiences as well as the underpinning theory, in order to hone their own conceptual understanding of their roles and identities as teachers (CHE 2011).

Of particular importance is that this kind of learning is not limited to school-based teaching experience or so-called 'teaching practice', but needs to be integrated across the learning programme, hence the notion of 'work-integrated learning' (WiL). Student teachers thus need to learn about practice, in practice, from practice, for practice, and ultimately, to practise. Such learning needs to be contextualised, enabling students to facilitate learning in authentic South African school contexts across an array of school types, ranging from under-resourced schools in poverty-stricken areas to well-equipped schools in affluent communities. In this regard, Matoti and Odora (2013:126) identify integration of theory and practice as one of the key aims of the teaching experience, arguing that,

[...] the aims of the teaching practice experience are to provide opportunities for student teachers to integrate theory and practice and to work collaboratively with and learn from the teachers to prepare a competent, effective and efficient teacher, and to promote ongoing professional development and induction into the teaching profession.

The re-conceptualisation of mere 'practical experience' towards 'work-integrated learning' therefore necessitates a departure from former narrow and detached, disconnected conceptions of 'learning-to-work' towards assimilative aspects of such learning (CHE 2011). As teacher educators, we (the authors and our colleagues in the faculty) grappled with ways to enable our students, over the course of four years, to progress from 'theorising practice' towards integrating and 'practising theory' (Howard & Maton 2011). In order to facilitate such a progression through curriculum design and implementation, we considered questions such as:

• How do we conceptualise such an integrated curriculum?

• How much time should be devoted to school-based experiences?

• How should this be spread across the programme?

• How can we ensure that these experiences are indeed meaningful and that they facilitate students' professional learning?

In this paper, we share aspects of our faculty's transformative journey as we grappled with these questions. We explain the construction of dialogic spaces and 'learning walks'1 (Steiny 2009), the name given to experiences and the dialogic spaces created to develop and inform a new model of WiL, as we aimed to facilitate the assimilation of work-based learning into our curricula, in other words, to promote a connection between theory and practice in our teacher education programmes. The foundation of this transformative journey was the development of a humanising curriculum framework that was co-constructed within the faculty over an extended period of time. The application of this framework led to the implementation of 'learning walks' as we aimed to design integrated, coherent new BEd programmes.

Background

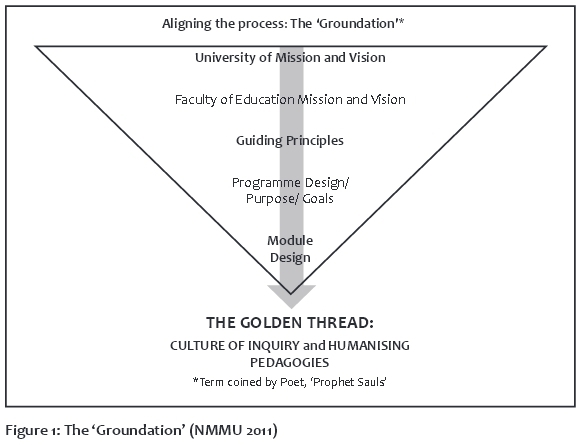

In July 2011, the faculty finalised its new vision and mission after a two-year period of workshops and dialogues focussed on interrogating the previous and current paradigms and practices in the Faculty of Education. The development and acceptance of the new vision and mission necessitated a comprehensive and intensive process of curriculum renewal. During this process, several 'models' were developed to explain how we would go about doing this work. The first of these models (Figure 1) was named the 'Groundation,2 a term coined by a local poet and member of the school governing body (SGB) at one of the schools, and with whom we were working. The conjoined concept of foundations which grounded our work in the everyday reality of schools seemed apt to describe what we were trying to do. Essentially, the Groundation model captured the layered and textured nature of our process, with the 'golden thread' of a humanising pedagogy and a culture of inquiry running through it. The diagram in Figure 1 was designed with the assistance of Dr Carol Rodgers, a Fulbright scholar from the USA working with us in 2011.

This part of the renewal process was characterised by a series of inclusive and participatory conversations drawing on various voices across a wide spectrum of stakeholders, including students, alumni, teachers, and so forth. The series of engagements enabled us to develop a shared understanding of our philosophy of teacher education, rooted in humanising pedagogies advocated by critical theorists such as Paulo Freire (1993) and Bartolome (1994) and humanist educational philosophers such as Dewey (1938), Hawkins (1974) and Palmer (1998). For our 'groundation', we identified six key aspects to focus on in the conceptualisation of our new teacher education programmes. These were teaching, learning, assessment, research, context and knowledge. The following formulations were developed by Dr Carol Rodgers in October 2011 based on ideas arising from participatory workshops that she facilitated and which involved teams of educators in the faculty:

• Teaching we define as a process of inquiry and reflection. It starts from and is guided by what students know, and know how to do. Teaching is deeply linked to assessment. It is a relational act calling for compassion. The purposes of teaching reach beyond the classroom and the individual to the growth and health of the community, South Africa and the planet.

• Learning is conceptualised as a human, social and constructivist process. It involves making meaning from experience, both past and present, both real and imagined. All learning calls upon the vast capacities of all learners. It is 'the thing that makes us human', and involves feelings of liberation, expansion and power. It serves to contribute to the good of the larger society and the planet.

• Assessment of teaching and learning is understood as the starting place of growth. Assessment tells teachers both what and how to teach. It is important that teachers know what students know and feel, as well as what they know themselves. Effective assessment calls upon the capacity of the teacher to be present to students and their learning. Effective assessment of one's own teaching is based upon effective assessment of students' learning. Such evidence guides teaching.

• Another guiding principle deals with research, which we define as a deliberate process of enquiry. It ranges from play to peer-reviewed, highly structured studies. It can be done by anyone, from a child to a professional scholar. It is a natural part of life and deeply linked to what makes us human, namely, a desire to explore the world and to find out what it means and our place in it. In this regard, we argue that learning, teaching and assessment are research.

• As guiding principle we also acknowledge the importance of context. We recognise that we operate in multiple contexts, culturally, socially, politically, economically and historically, and are shaped by each of these. An awareness of these various contexts and the power dimensions inherent in them, especially in post-colonial, post-apartheid South Africa, need to be nurtured.

• The final principle directing our understanding of teacher education deals with the notion of knowledge. In this regard, we hold that a teacher must be deeply grounded in the subject matter of education and its disciplines. In the case of the subject matter of education, we argue that grounding in historical and contemporary orientations and issues, for example, philosophical foundations, political outlooks, economic realities and sociological factors, is essential. With regard to disciplinary knowledge of the subject, we believe that a teacher must be deeply grounded in the ways of thinking of that particular discipline, in other words, historical or scientific thinking, as well as in the connected knowledge of the discipline, for example, concepts, principles, theories and themes that incorporate but do not rely exclusively on facts, and be able to translate that knowledge into learning activities (NMMU 2011).

Specific competence areas were also identified, which correspond with learning categories essential for teacher education as described in the Minimum Requirements for Teacher Education Programmes (RSA DHET 2011).

The development of the 'Groundation' model was a critical milestone in our journey, as it made us revisit individual teaching philosophies, pedagogies, experiences and identities shaped by diverse histories and biographies. The model was a thinking device that helped us to examine and redefine these in the light of what new generations of teachers required of us and our programmes. This provided the grounding for our humanising curriculum framework, which evolved after subsequent creative engagements.

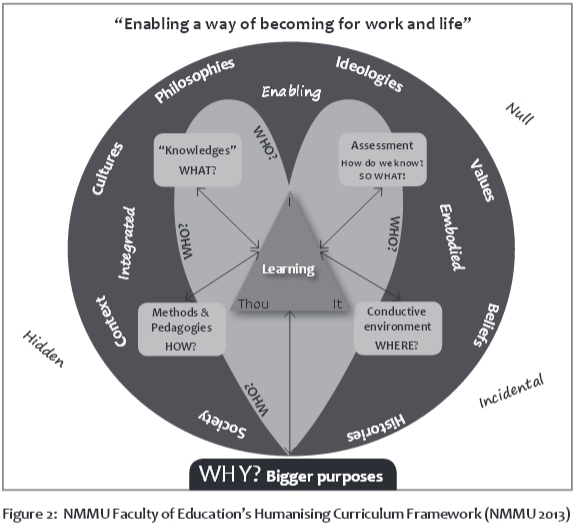

The next significant milestone in our collective engagement in curriculum renewal was the humanising curriculum framework, illustrated in the diagram in Figure 2.

There are several layers of meaning encapsulated in this diagram. The outer layer of the circle acknowledges that our work in education, and all who engage in it, are informed by and seek to contribute to the range of historical, philosophical, political and cultural dimensions of our lives within a society. Central to the educational project is the goal of learning, which is captured and enabled by the interactional relationship of the "I-thou-it" triad (Hawkins 1974:48), where 'I' is the teacher, 'thou' the learner, and 'it' the subject matter. Informing the interactional relationship are the understandings and philosophical orientations of our 'golden thread' of humanising pedagogies and a culture of inquiry. These led us towards a set of fundamental questions guiding the curriculum choices we need to make, namely: what do we choose to teach or learn? (the content of the curriculum); how will we do so? (the pedagogies); where will this learning and teaching take place and be set up? (environments that are conducive to learning); and how do we know that learning has taken place? (the 'so what?' or assessment question). Integral to all these questions is the most important one, the 'who question' (relating to the human beings engaged in the educational interaction). The model depicts the connections to the 'who' element in a heart formation running through all the other questions, as it personifies the humanising element, and indeed goes to the heart of the choices made in response to all the other questions. The 'why question' underpins all of it, as it relates to the purpose of education, of teaching and learning, and how it serves society. The caption, 'Enabling a way of becoming for work and life', speaks both to "the NMMU story",3 in which we see the goal of "graduateness" as preparing students "for work and life" (NMMU 2013:5), as well as to the underpinning philosophy central to a humanising pedagogy as espoused by Freire and others, namely that we are always in the process of 'becoming'; indeed, this humanisation is the "ontological vocation" of human beings (Freire 1993:75).

Transforming teaching practice

The notion of 'teaching practice', its role, function and foundations, emerged frequently during our curriculum renewal conversations. Ambiguous conceptualisations, approaches and practices clearly existed, causing growing discomfort and unease. A pertinent concern was the perpetual embodiment of some tenets of erstwhile philosophies and pedagogies, evident in an obsession with the "right method" (Bartolome 1994:174), which contradicted our faculty's transformative vision, mission and humanising pedagogy. It was thus of utmost importance to also interrogate and critique existing assumptions and practices of student teaching.

Our interrogations guided us to a number of realisations. First, our current teacher education curricula were designed according to a theory-led and not an integrated praxis-led approach, with theory being covered during the first three years of students' studies, followed by practical 'application' in the final year. This model had been one of those put forward as a possibility for teacher education by the Ministerial Commission on Teacher Education (RSA DoE 2005) before the final recommendations of this commission were accepted, which then did not advocate for this model. But in anticipation, NMMU had adopted what was known as the '3+1' model, whereby students embarked on the practicum component only after having engaged with theoretical knowledge and having been equipped with all the assumed conceptual tools needed for teaching practice (Morrow, Samuels & Jiya 2004). Propositional knowledge is thus obtained in a formal university context, and only thereafter are students afforded the chance to put this into practice in real-life contexts. Teacher education is therefore seen as

[...] a theoretically informed field and [...] student teachers first need to acquire theoretical and conceptual knowledge through course work in order to put the knowledge they have gained into practice (Reeves & Robinson 2014:238).

This model is also premised on a deductive relationship between theory and practice, based on the assumption that students by default have the ability to transfer and apply theoretical and conceptual knowledge to practice (Clarke & Winch 2004, cited in Reeves & Robinson 2014). The result is a reductionist conception of teacher education with a primary focus on a ready-made toolkit of teaching tips and 'good ideas' for the classroom (Ensor 2004). As our students spend a significant period of time at a particular school during their final year, for practical reasons, they tend to go back to familiar environments. Hence their exposure to alternative contexts is limited. Furthermore, a dominant focus on summative assessment associated with the '3+1' model encourages students to present what lecturers call 'Christmas tree' lessons, with students more concerned about achieving good marks for their 'crit' lesson than learning how to teach by observing, reflecting and experimenting followed by more reflection.

We have tended, as part of our previous teacher education paradigm and practices, to adopt a technicist stance, whereby our student teachers become the passive recipients of professional knowledge (Zeichner 1983). Similar to Freire's (1993) notion of a 'banking' approach, our teacher education programmes became the 'depositors' of information and our student teachers' the 'depositees'. Anecdotal accounts by student teachers highlighted that we were indeed training them as classroom managers, essentially practising primarily skills-based education. Teachers produced by a technicist model preparation programme are trained to follow instructions explicitly, uncritically and compliantly. In essence, teachers are portrayed as skilled technicians (Owen-Jackson & Fasciato 2013). Within the technicist paradigm, the primary role of the teacher is thus seen as managing the delivery of course material. We realised that while our new graduates were certainly competent to deliver the national school curriculum of the day as mandated by the Department of Basic Education (DBE), an outside source (the DBE) was in actual fact determining the classroom curriculum and methods of instruction. Such an approach necessarily leads to detachment from the human beings the teachers encounter in the classroom and the diversity it holds within context. It also downplays the importance of integration between theory and practice.

We realised that our approach to teaching practice was indeed promoting and emphasising technical knowledge (Schulz 2005). This kind of knowledge however constitutes only a small part of teachers' knowledge and is not sufficient for student teachers' professional learning. In this regard, Darling-Hammond (1999) argues that 'technical' teaching practice experiences can socialise student teachers and other stakeholders into maintaining the status quo rather than developing a critical inquiry approach underpinned by lifelong learning. The implication is that teaching practice is so distinctive and pragmatic that developing some kind of language with which lecturers, mentor teachers and student teachers may communicate about their work becomes very difficult.

It was as a result of this analysis that lecturers in the foundation phase curriculum renewal team embarked on what they came to call 'learning walks'. The 'learning walks' entailed embarking on a range of educational experiences involving visits to schools that would enable prospective teachers and lecturers to understand the intricacy of early years' education and to engage creatively and courageously within the sphere of teacher education. It involved finding ways to invite lecturers and students into discomfort and into contested spaces.

The question that informed the ensuing work described in the rest of this article could be stated as follows: Is there alignment between what lecturers are teaching in the BEd programme and what they observe on the 'learning walks' about learners, classroom resources and teachers/teaching in the schools? A complementary question posed by one of the lecturer participants provided an important lens through which to engage in the 'learning walks': How, through the selection of content and assessment, does the lecturerinclude and/or exclude students from active participation? Do the practice and theory we teach repress and silence students and possibly rob them of their language, culture, history and values when we observe them during practice teaching?

Method of inquiry

One of the major tasks of our BEd curriculum renewal teams was to approach curriculum renewal in a non-technicist manner. In order to do so, and in accordance with the faculty's meta-transformative journey, we adopted a dialogical approach. This approach allows for professional learning in which integration happens through participation in social practice, namely by engaging in the actual realities of classrooms. In such a setting, productive action and understanding are dialectically related (Lave & Wenger 1991) and interpersonal transactions create patterns of meanings, values, and integration (Gallimore & Tharp 1990).

During our curriculum renewal journey, we thus took on the stance of learners ourselves, eager to connect theories of teacher education with practice by also learning through experience (Dewey 1938). Increasingly, we came to the disconcerting realisation that our expectations as lecturers of student teachers and our programmes were fundamentally incompatible and often opposing. We discovered that we had taken on the role of the 'knower', advocating various teaching and learning theories, and that this stance reinforced the disjunction between theory, reality and practice (Smith-Lovin 2007).

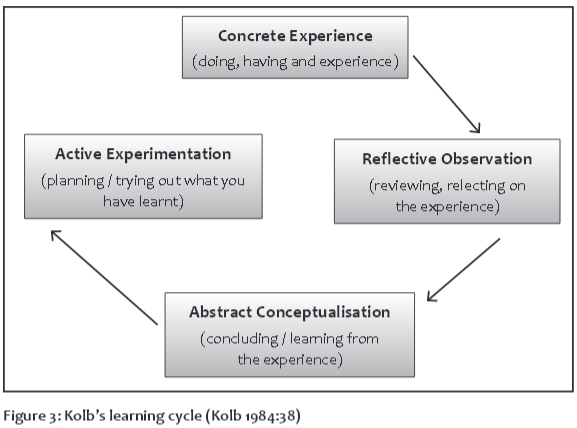

The well-known learning cycle model of Kolb (1984) forms the foundation of many current workplace-based curriculums (CHE 2011), and we proceeded to apply it to our own learning as well. We embarked on a series of 'learning walks' with our partners and co-participants, which included students, alumni and teachers. Kolb's model involves four consecutive stages, as shown in Figure 3.

The cycle starts with concrete experience, and its importance is premised on the belief that one cannot learn something simply by watching it or reading about it. Active involvement is necessary. It was thus important for us to have first-hand experience of the situation. The next phase in the cycle is reflective observation, which implies that attention should be focused on particular elements of the experience. This means pausing to consider what has just taken place. This phase is followed by abstract conceptualisation, during which we had to analyse our observations and explain and integrate them into logically sound theories through a process of inductive reasoning. The final phase involves active experimentation. During this phase, we considered how to put into practice what we had learnt (Gosling & Moon 2001).

Schön (1983) and Biggs (1999) advocate the notion of reflection as critical to learning. Biggs (1999), for example, argues that observation and reflection are prerequisites for learning. In order to learn, we also need to develop concepts that will enable us to make meaning of the experience, where after we need to be afforded opportunities to apply and experiment with these concepts during new experiences (CHE 2011).

Hence, as part of our experiential and reflective 'learning walks', which were designed to enable the manner of learning depicted in Kolb's cycle, we initiated various activities that allowed our students to become co-investigators, continuously attempting to reduce the dichotomy between theory and practice. Activities included visits to classrooms in contexts unfamiliar to both the lecturers and students, and for co-teaching in spaces created within the security of the learning community that was set up in and with these schools. As curriculum renewal programme team members, and therefore teacher-learners ourselves, we took part in activities where, both as individuals and as a team, we negotiated meanings and developed knowledge within 'real' social contexts. This led to a reconceptualisation of the relationships between different participants in the learning experience. We continually amended our practices in our own classrooms as well as our ways of working with our students. Through this collaborative and participative methodology we were able to see how the curriculum could be strengthened by integrating theory and practice. The engagement processes in these 'learning walks' shaped our understanding of how to align and integrate theory and practice in our programme, providing real experience and models of integration for us to use in our curriculum renewal work.

'Learning walks': The settings and the data

We utilised the notion of 'learning walks', described as "visits to classrooms by a small team of school adults using a specific protocol" (Steiny 2009:31), as mode of inquiry-based learning to enter into spaces which were unfamiliar to several of the staff and students, in that they were located in severely under-resourced schools in poor townships that are often regarded as 'dysfunctional' for these reasons. From the outset, we did not 'enter the field to gather research data' on teaching practice. Rather, we regarded ourselves as being in the field as teacher-learners and "members of the landscape" (Clandinin & Connelly 2000:63), always in relationship with our co-participants, namely teacher education colleagues, students and mentor teachers.

The questions we posed (see earlier section of this article) directed our 'learning walks', taking us into diverse learning spaces and environments where we believed our best thinking would take place. We chose two schools situated in poverty-stricken townships in the Nelson Mandela Bay area. We met and negotiated with the school principals to allow our team, consisting of lecturers and student teachers, to observe classroom practices and present a few lessons. To further improve integration of theory and practice in our programmes, we also engaged our student teachers in processes to facilitate and enhance both our and their learning by engaging in reflection and feedback on the effectiveness of their and our learning efforts within these contexts. We set up conversational processes, where we (the foundation phase team) shared feedback sessions with the teachers who allowed us into their classrooms to observe and to teach, with the aim of finding common ground and affording role players the chance to understand each other. Our students, who co-taught with us, were invited to participate as well. We thus created learning 'dialogical spaces' where teacher educators and students' individual truths and stories were acknowledged and respected and where all participants could learn and grow around controversial issues (Rule 2004). Lecturers, mentor teachers and student teachers were enabled to reflect on and talk about their experiences together, emphasising and encouraging group discussion and decision-making in a collegial atmosphere, where we regarded each other as peers.

We took extensive written notes and audio recorded the groups' activities. The notes and recordings constituted the data, which were collectively analysed immediately after the classroom experiences. We adhered to the guidance of Baker, Jensen and Kolb (2002) by respecting each other, being receptive to differing points of view, taking time to reflect on consequences of action, ultimately aiming to facilitate our own growth and development through this process:

Freire (1993:80) holds that,

Through dialogue, the teacher-of-the-students and the students-of-the-teacher cease to exist and a new term emerges: teacher-student with students-teachers. The teacher is no longer merely the-one-who-teaches, but who is himself taught in dialogue with the students, who in turn while being taught also teach.

The data generated indicated that as lecturers, teachers and students, we had indeed co-created the learning experience through dialogue. For example, one student noted:

Telling our stories and sharing our experiences allowed us to name it, to reflect critically on it and to act upon it in a mutually respectful manner.

This same awareness emerged from a lecturer's response:

Creating areas of mutual vulnerabilities allowed us to move out of our comfort zone into discomfort and to critically think about the challenges and context within which my students are supposed to teach.

These two examples reflect a gradual but noticeable shift in focus as our 'learning walks' progressed. Increasingly, it became evident that all participants were slowly departing from measures of organisational performance, which were often limiting and subject to short-term manipulation at the expense of long-term integration between theory and practice.

All the accounts produced by the participants during the 'learning walks' were taken into consideration and analysed in order to identify significant patterns of consistency and variation. Open-ended questions allowed participants to reflect on alignment between what is taught in the lecture halls and the contextual realities of classrooms. Some examples of such questions were:

• Give one word that best describes your experiences whilst observing the classrooms.

• Is there alignment between what you teach and who the learners in the classrooms are?

• Is there alignment between the teaching aids you use and the classroom reality?

All written notes and audio recordings were transcribed and the data analysed using grounded theory. As such, we allowed the data to inform the analysis, rather than forcing a priori categories to fit (Glaser 2011). As a team, we read through all the transcripts as we attempted to design an integrated, coherent new BEd foundation phase programme that is responsive to the realities of the schools of the majority and which facilitates connection between theory and practice. We wrote codes in the margins, creating short line-by-line units and staying as close to the participants' words as possible (Foss & Waters 2007). After finalising line-by-line codes, we lifted the codes and corresponding text and re-categorised these into focused codes (Charmaz 2006) based on what we saw as connections across line-by-line codes that represented larger themes. We then physically cut these line-by-line units out, with only a colour-coded system as to who said what, and created piles of data that shared similar themes. These piles were checked for consistency and put into envelopes, each titled with a label that described the elements needed for our work-integrated model. As we arranged these elements and thought about the relationships between them, our conceptual framework to design an integrated, coherent new BEd programme emerged as the story these labels told together (Foss & Waters 2007).

Towards an integrated BEd curriculum

The aforementioned initiatives led us to a dialogical approach towards designing an integrated, coherent new BEd programme, closing the loop and facilitating connections between theory and practice. One student's feedback noted:

So now, the reality of me going to schools where I've got these good intentions and like I did all my methods and I've studied really hard in my methods. I know what I am doing, I've made my flash cards and for Maths I've made my clock and I've made my 'tema boks'... I've done all these things and I've got these beautiful things but I cannot actually apply it because I cannot respond to them. Like when you talk about emotions, since Life Skills deals with emotions, and feelings describe me. Like don't ask me how I feel in Afrikaans because I don't feel in Afrikaans. I feel in English.

The core transformations in terms of our (re)conceptualisation of work-integrated learning (WiL) are summarised in tabular format below as grounded in our guiding principles:

It is our contention that the proposed new WiL model as described above will generate the destruction of silo walls and the assimilation of practice-based learning experiences into our BEd programmes in meaningful ways that optimise student teacher learning and development.

Conclusion: the world of work and the world of learning

The critical importance of work-integrated learning experiences is emphasised by the CHE:

[...] programmes that promote graduates' successful integration into the world of work and that enable graduates to make meaningful contributions in contexts of development require innovative curricular, teaching, learning and assessment practices (CHE 2011:3).

Within the context of teacher education, the term 'work-integrated learning' thus emphasises an incorporation of knowledge and skills acquired at teacher education institutions within experiences in the workplace (Coll, Eames, Paku et al 2008). It also refers to all and any learning that is situated in or arising from the workplace. Hence teacher educators need to develop both generic and specific competencies that will enhance teacher effectiveness by optimising integration between theory and practice (Fleming, Martin, Hughes & Zinn 2008).

Designing teacher education programmes that successfully merge student teachers' experiences in the workplace with theory introduced at our institution was one of the key curricular and pedagogical reform challenges encountered during our curriculum renewal process. From the outset, we believed that such integration called for collegial discussions between student teachers, mentor teachers and lecturing staff. The re-curriculation of our BEd programmes was thus not driven by predefined inputs from lecturers, but negotiated and co-constructed by all role players engaged in work-integrated learning experiences. As teacher educators and curriculum designers we made conscious shifts, spontaneously shaping, constructing and reconstructing work-integrated learning experiences to optimise integration between theory and practice.

We argue that teacher educators and curriculum designers need to make themselves vulnerable, adopting the identity of learners who are willing to embark on disrupting and transformative 'learning walks'. Teacher educators too need to traverse from silo to splice, appreciating the importance of both classroom and field educational experiences, ultimately learning that there is nothing more practical than a good theory.

References

Baker, A., Jensen, P. & Kolb, D.A. 2002. Conversational learning: An experiential approach to knowledge creation. Westport, CT: Quorum Books. [ Links ]

Barnett, B. 2006. Adobe Mentoring Protocol. Leadership Development. Services, LLC. Victoria, Australia: Hawker Brownlow Education. [ Links ]

Bartolome, L.I. 1994. Beyond the methods fetish: Toward a humanising pedagogy. Harvard Educational Review, 64(2):173-194. [ Links ]

Biggs, J. 1999. Assessing for learning: Some dimensions underlying new approaches to educational assessment. The Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 41(1):1-17. [ Links ]

Charmaz, K. 2006. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

CHE (Council on Higher Education). 2011. Work-Integrated Learning: Good Practice Guide. HE Monitor, No 12. Pretoria: CHE. [ Links ]

Clandinin, D.J. & Connelly, F.M. 2000. Narrative Inquiry: Experience and Story in Qualitative Research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers. [ Links ]

Coll, R., Eames, C., Paku, L., Lay, M., Ayling, D., Hodges, D., Ram, S., Bhat, R., Fleming, J., Ferkins, L., Wiersma, C. & Martin, A. J. 2008. An exploration of the pedagogies employed to integrate knowledge in work-integrated learning in New Zealand higher education institutions. Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Education. [ Links ]

Darling-Hammond, L. 1999. Educating teachers for the next century: Rethinking practice and policy. In G. Griffin (Ed.), The education of teachers: 98th NSSE Yearbook, Part I. Chicago: NSSE. 221-256. [ Links ]

Dewey, J. 1938. Experience and education. New York: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Ensor, P. 2004. Modalities of teacher education discourse and the education of effective practitioners. Pedagogy, Culture and Society, 12(2):217-232. [ Links ]

Fleming, J., Martin, A.J., Hughes, H. & Zinn, C. 2009. Maximizing work-integrated learning experiences through identifying graduate competencies for employability: A case study of sport studies in higher education. The Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education, 10(3):189-201. [ Links ]

Foss, S.K. & Waters, W.J.C. 2007. Destination dissertation: A traveller's guide to a done dissertation. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. [ Links ]

Freire, P. 1993. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum. [ Links ]

Gallimore, R. & Tharp, R. 1990. Teaching mind in society: Teaching, schooling, and literate discourse. In L.C. Moll (Ed.), Vygotsky and Education: Instructional Implications and Applications of Sociohistorical Psychology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 175-205. [ Links ]

Garm, N. & Karlsen, G. 2004. Teacher education reform in Europe: The case of Norway - Trends and tensions in a global perspective. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20:731-744. [ Links ]

Glaser, B.G. 2011. Getting out of the data: Grounded theory conceptualization. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press. [ Links ]

Gosling, D. & Moon, J.A. 2001. How to use learning outcomes and assessment criteria. London: SEEC Office. Retrieved from http://www.aec-music.eu/userfiles/File/goslingmoon-learningoutcomesassessmentcriteria(2).pdf (accessed 22September 2014). [ Links ]

Hawkins, D. 1974. The Informed Vision: Essays on Learning and Human Nature. New York: Agathon Press. [ Links ]

Howard, S. K. & Maton, K. 2011. Theorising knowledge practices: A missing piece of the educational technology puzzle. Research in Learning Technology, 19(3):191-206. [ Links ]

Kolb, D. 1984. Experiential Learning. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Lave, J. & Wenger, E. 1991. Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Lawrence, G. & Palmer, D. 2003. Clever Teachers, Clever Sciences. Preparing teachers for the challenge of teaching science, mathematics and technology in 21st century Australia. EIP Study No. 03/06. Canberra: Department of Education, Science and Training. [ Links ]

Matoti, S.N. & Odora, R.J. 2013. Student teachers' perceptions of their experiences of teaching practice. South African Journal of Higher Education, 27(1):126-143. [ Links ]

Morrow, W. 2007. Learning to teach in South Africa. Pretoria: HSRC Press. [ Links ]

Morrow, W., Samuels, M. & Jiya, Y. 2004. Creating critical discursive spaces for professional teacher development: Research, policy, theory and the practice of teacher education in context. In Developing the field of teacher education in South Africa: Some aspects of the work of the NCTE: Chapter 2. Uncited reference in CEPD 2009a.

NMMU. 2011. The Groundation. Port Elizabeth: Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University Faculty of Education. [ Links ]

NMMU. 2013. Humanising curriculum framework. Port Elizabeth: Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University Faculty of Education. [ Links ]

Owen-Jackson, G. & Fasciato, M. 2013. Sustaining teacher education: Does where you learn to teach make a difference to the teacher you become? PATT 27 Presentation. Christchurch: The Open University. [ Links ]

Palmer, P. 1998. The Courage to Teach. San Francisco, CA: Josey-Bass. [ Links ]

Reeves, C. & Robinson, M. 2014. Assumptions underpinning the conceptualisation of professional learning in teacher education. South African Journal of Higher Education, 28(1):236-253. [ Links ]

RSA DHET (Republic of South Africa. Department of Higher Education and Training). 2011. The Minimum Requirements for Teacher Education Qualifications. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

RSA DoE (Republic of South Africa. Department of Education). 2005. Report of the Ministerial Committee on Teacher Education: A National Framework for Teacher Education in South Africa. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Rule, P. 2004. Dialogic spaces: Adult education projects and social engagement. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 23(4):1-12. [ Links ]

Schon, D.A. 1983. The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books. [ Links ]

Schulz, R. 2005. The practicum: More than practice. Canadian Journal of Education, 28(1/2):147-169. [ Links ]

Shulman, L. 2004. The wisdom of practice: Essays on teaching, learning, and learning to teach. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Smith-Lovin, L. 2007. The strength of weak identities: Social structural sources of self, situation and emotional experience. Social Psychology Quarterly, 70:106-124. [ Links ]

Steiny, J. 2009. Learning Walk. Build hearty appetites for professional development. Journal of Staff Development, 30(2):32-36. [ Links ]

Zeichner, K.M. 1983. Alternative paradigms on teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 34(3):3-9. [ Links ]

* Email address: Denise.Zinn@nmmu.ac.za

Note that although the imperative 'will' is used in this section, these are recommendations to the team constructing the renewed curriculum.

Endnotes

1. 'Learning Walks' (Steiny 2009) is a term used to describe visits to classrooms by small teams, usually of adults wishing to help them to learn and understand the 'big picture' of how the school works. This team had not read the Steiny article, but were attracted to the idea when it first came up in a curriculum renewal discussion facilitated by Dr Carol Rodgers.

2. With recognition to Andrew Sauls, poet from Port Elizabeth and SGB member of one of the schools in the Manyano network.

3. This is a narrative version of NMMU's strategic plan, developed in 2011, underpinning and anticipating the realisation of Vision 2020 (V2020).