Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Childhood Education

On-line version ISSN 2223-7682

Print version ISSN 2223-7674

SAJCE vol.4 n.3 Johannesburg 2014

ARTICLES

Reflections on the development of a pre-service language curriculum for the BEd (Foundation Phase)

Vuyokazi Nomlomo*; Zubeida Desai

University of Western Cape

ABSTRACT

The initiative of the Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) in South Africa to strengthen foundation phase teaching has resulted in the development of new foundation phase (Grades R-3) programmes at institutions that did not previously offer them. In this article we reflect on the conceptualisation and development of a pre-service language curriculum for one such programme. We base our discussion on principles that underpin teacher education programme development for early childhood education and on issues and insights about appropriate language curriculum content for a foundation phase teacher. Whilst awaiting the outcome of our accreditation, the authors, as two of the persons who assisted in the design of the language curriculum, thought it appropriate to subject the curriculum to an internal scrutiny whilst we prepare to offer the programme. This internal dialogue is informed by the literature on early language development, particularly in multilingual contexts such as in South Africa.

Keywords: pre-service teacher education, language curriculum design, multilingual contexts, home language development; foundation phase

Introduction

As a response to the shortage of foundation phase teachers, the Department of Higher Education (DHET) took the initiative to strengthen foundation phase (FP) teaching by increasing the number of institutions offering FP programmes. The DHET, in collaboration with the European Union (EU), offered financial support to institutions to develop new pre-service four-year BEd programmes for the FP and develop scholarship in this field. Many institutions collaborated in the form of consortia to strengthen programme development in FP teaching. These consortia were involved in research that guided the development of new FP programmes and capacitated postgraduate students in preparation for the implementation of programmes in different institutions. The University of the Western Cape (UWC) was part of the Cape consortium - which included three other institutions in the Eastern Cape, namely Rhodes University (RU), Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University (NMMU) and Walter Sisulu University (WSU) - in the EU-funded initiative to develop a BEd (FP) programme.

Given the autonomy of higher education institutions, there is no national curriculum for teacher education and institutions have to design their own curricula, guided by national policy (Kwenda & Robinson 2010). In this article, we reflect on the conceptualisation and development of a language curriculum for a four-year BEd (FP) programme, which was designed as one of the deliverables of the EU-DHET-funded projects for strengthening FP teaching. The aim of this article is to share our experiences with regard to the principles, philosophy and theoretical framework that guided the development of the BEd (FP) programme, particularly with regard to the language curriculum within this programme.

The role of language in learning

Language plays a crucial role in learning as it is through language that children develop ideas or concepts of the world around them; it is through language that children make sense of the input they receive in the classroom from the teacher and the written texts; and it is through language that children express their understanding of what they have learnt from this input (Desai 2012:1).

As language development in the foundation phase is a crucial aspect of children's general conceptual development, we decided to interrogate the language curriculum we have designed in an attempt to improve it before we start offering the programme in 2016. Our aim is to offer an appropriate language curriculum for teacher education that will enable pre-service students to understand the current literacy problems in early childhood, whilst equipping them with suitable knowledge and skills to address these problems in a holistic manner. This philosophy is influenced by our understanding of teaching as a complex activity that integrates different types of knowledge and skills (Fitzmaurice 2010; RSA DHET 2008) and our inclusive and reflective approach to teacher education (Ashby, Hobson, Tracey et al 2008; Darling-Hammond & Bransford 2005; Kemmis 2011), with specific reference to language teacher education curriculum content for the FP. It is also motivated by the need for more and better trained teachers (Kanjee, Sayed & Rodriguez 2010; Kwenda & Robinson 2010), particularly those that can teach literacy in African languages in the FP (Foley 2001; Murray 2009). The overarching question that guides this articleis: What language content and pedagogical skills do pre-service student teachers need to teach literacy well in the FP classes and to enable FP learners to use language as a tool for learning?

Guiding framework for the design of the curriculum

In the design of the language curriculum for the FP programme we were guided by the institutional and the faculty philosophy, the initial teacher education principles, the course content principles, and the implications of these principles for literacy development in early childhood education in multilingual South Africa.

The BEd (FP) Programme: Purpose and institutional philosophy

The general purpose of the FP programme is to provide a four-year BEd degree with the aim of training well-grounded and competent FP teachers who will have adequate knowledge and skills to facilitate learners' epistemological access to the foundation phase curriculum in the subject areas of language and literacy, numeracy, and life skills, and who will be able to teach in the learners' home languages. It also aims at exposing pre-service students to diverse and inclusive learning environments in order to understand the complexities and dynamics of teaching in the South African context.

With regard to the institutional philosophy, we had to consider the institutional vision and mission, as well as the conceptual framework that guides programme development across the faculties. The mission of the institution is to provide students from disadvantaged educational backgrounds not only access to higher education, but also success in it, and to strive for excellence in teaching, learning and research. Currently, one of the major challenges in the South African education system is unevenness in performance along social class and racial lines. The FP programme at UWC therefore aims at recruiting a diverse cohort of students and providing a nurturing and supportive environment for the success of all students. At least 50% of the first FP cohort will be home language speakers of isiXhosa, a much neglected language in education.

As literacy is one of the main challenges in basic education at the moment, particularly among disadvantaged groups of learners, this programme seeks to produce young teachers who will be able to respond meaningfully to this challenge and contribute to the transformation of their own communities through innovative pedagogical practices and also through research that enhances literacy development. As a way of responding to the education faculty's strategic plan for the period 2010 to 2014, this programme is aligned with the Institutional Operation Plan (IOP), which emphasises certain graduate qualities aimed for in the teaching and learning of the students, including the key attributes of critical thinking, lifelong learning and digital literacy.

Initial teacher education principles

The general view, both at the national and international level,is that teacher education is a complex activity that integrates many kinds of knowledge which have to be applied in diverse contexts, and also involves issues of identity (Ashby et al 2008; Darling-Hammond & Bransford 2005; Fitzmaurice 2010; Grosser & De Waal 2008; Kemmis 2011; Korthagen & Kessels 1999; RSA DHET 2008; Rusznyak 2009). According to the Minimum Requirements for Teacher Education Qualifications (MRTEQ), the different kinds of knowledge that student teachers should be exposed to during their training include disciplinary (content) knowledge and pedagogical knowledge (RSA DHET 2011). Disciplinary knowledge has to do with subject (discipline) matter knowledge, while pedagogical knowledge exposes students to various methods of presenting the content of a particular subject or discipline to learners (RSA DoE 2005; RSA DHET 2008; 2011). Students should also have opportunities for practical, fundamental and situational learning during their pre-service training. These kinds of knowledge influence the content (what is taught); the learning process (practice); and the learning context (classroom environment and policies) with regard to student teacher competences, such as practical, fundamental and reflexive competences, as they apply knowledge in different settings and situations (Grosser & De Waal 2008; RSA DoE 2005).

Learning to teach is, essentially, a sociocultural and a mediated process that involves interaction between individuals such as peers, learners, teachers and mentors (Darling-Hammond & Bransford 2005; Fitzmaurice 2010; Kemmis 2011; Korthagen & Kessels 1999). This interaction requires supervision, coaching and feedback to enable the students to apply the different kinds of knowledge in the classroom (Darling-Hammond & Bransford 2005). Therefore, learning to teach is both a cognitive and social process, which involves 'novices' and 'experts' (Shrum & Glisan 2000). As a social process, it is influenced by beliefs, attitudes and prior experiences about teaching (Ashby et al 2008) that may, in some instances, cause a tension between student teachers' beliefs and what they learn in the initial teacher education courses. This in turn, influences the manner in which they apply knowledge in the classroom as they learn to teach (Korthagen & Kessels 1999).

Designing a teacher education programme has to take into consideration the content, the learning process, and the learning context (Darling-Hammond & Bransford 2005). As we conceptualised the BEd (FP) language curriculum, these key elements were borne in mind, together with insights into what content and knowledge was appropriate in order for student teachers to teach early literacy skills to learners who come from diverse language and socio-economic contexts. We were also guided by our understanding of how young children acquire language and literacy skills in their home language, because teaching in the FP occurs in that language. Therefore, as we searched for language content that would be appropriate for the FP teacher, we also had to ensure that this knowledge was spread across the four years of the degree programme in an integrated manner, so as to enhance the depth of subject content knowledge and practical skills and to ensure coherence across the whole FP programme. This led to the design of a curriculum that considered the needs of the pre-service teacher with regard to disciplinary knowledge, pedagogical and practical skills, as well as the needs of the FP learner. As a result, the language and literacy curriculum incorporated the different types of knowledge at various levels of the programme with varying depth and credit weightings.

Course content principles

Multilingual approach and student teachers' individual needs

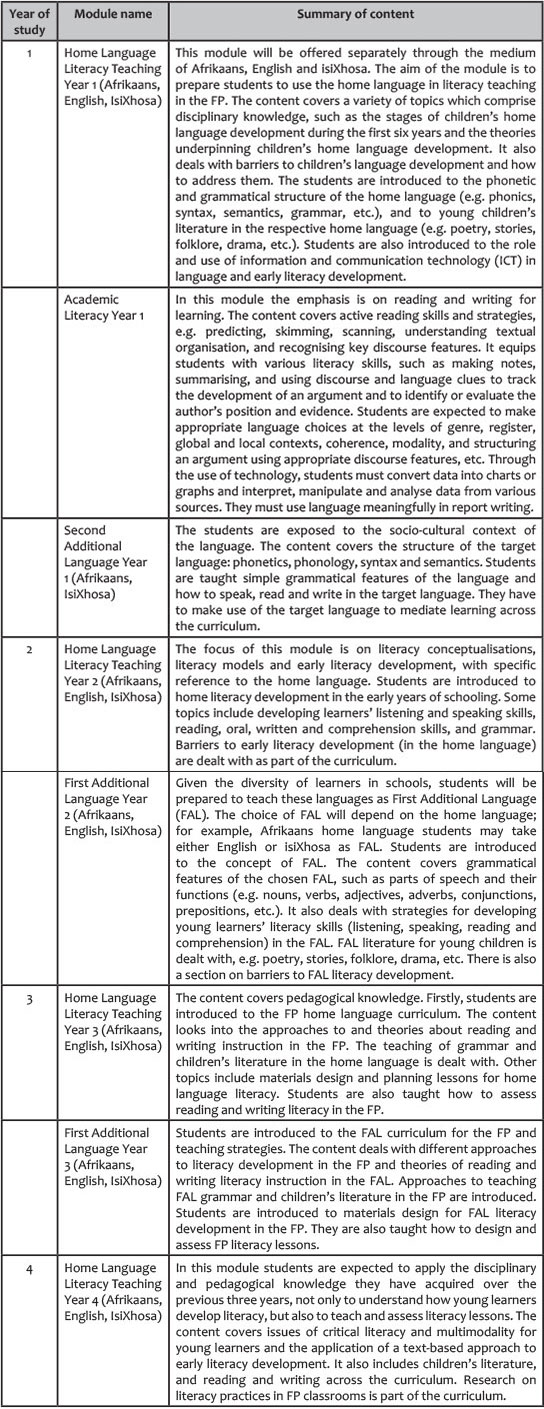

Concerning the selection of content for the BEd (FP) programme, it was not easy to select appropriate content, as most of the faculty members had no formal experience of FP teaching. To bridge this gap, we consulted with colleagues at institutions that were already offering FP programmes. We also learned from our own experiences as language teacher educators and reviewed literature and research on early literacy. This exercise assisted us in thinking through some of the principles that would underpin the content, while others emerged in the process of the curriculum design. Our curriculum design took into account that it should cater for students from different language backgrounds, particularly Afrikaans, English and isiXhosa as the dominant languages of the Western Cape. The language curriculum comprises eight modules spread over the four years of the BEd (FP) programme.

The first principle pertained to strengthening the pre-service students' own literacy skills in their home languages, as they will be expected to teach in learners' home languages in the FP. This principle acknowledges that student teachers bring diverse individual needs to the training that may impact on their chances of success (Ashby et al 2008). These needs include subject content knowledge and an understanding of key concepts that learners must engage with in the classroom. In our design of the FP language curriculum, we therefore took into account that students' own literacy skills have to be strengthened. This was motivated by recent reports that teachers' literacy skills are low and that their pedagogical strategies do not adequately support young learners' literacy skills (see, for example, NEEDU 2012). This necessitated an inclusive and multilingual approach which ensured that the three dominant languages of the Western Cape, namely, Afrikaans, English and isiXhosa would be used as languages of learning and teaching in a number of modules, except for generic modules such as Academic Literacy.

In addition, provision has been made to support students' academic literacy skills, as they are expected to read and write across the disciplines that form part of the FP programme. Therefore, the programme design ensures that students encounter the various academic literacies and discourses across the teacher education curriculum, so as to bridge the gap between literacy learning (and teaching) for school purposes and the academic discourses needed for university education. The Academic Literacy module offered as a year-long module in the first year is designed to facilitate and develop academic literacies such as reading, information and digital literacies/competences, communication and presentation skills, and academic writing.

The overall aim is to prepare students for reading and writing across the teacher education curriculum.

Insights into early language development and FP learners' needs

Teachers are often blamed for children's underdeveloped literacy skills (Dornbrack 2009). In our planning we were guided by the understanding and principle that student teachers learn when they are immersed in theories about learning, development and subject matter (Darling-Hammond & Bransford 2005). Thus, when considering the language needs of FP learners, we inserted the theme of how young children acquire their home languages into the curriculum with the aim of exposing student teachers to solid disciplinary or subject content knowledge that they can apply to build young learners' competence in their home languages, as language plays a significant role in the construction of core knowledge (Henning & Ragpot 2014). Hence, during the first year of the programme the emphasis is on enabling student teachers to know the structure of the home language with regard to phonics, syntax, semantics, lexicon and grammar, so that they can provide proper support to young learners as they formally learn their home languages and also learn to read and write. Pre-service student teachers need knowledge of the language they will be teaching; that is, they need to be proficient in the language. But they also need knowledge about the language; that is, how the language is structured and how it functions in use. Finally, they need to know how language is used for learning, how concepts are developed in and through language. In addition, they also need to distinguish between the spoken and written word.

The module is designed with the understanding that pre-service teachers should have deep insight into language development in young children, which forms the foundation of early literacy development, so that they can be able to support young children's language learning (Whitehead 2007; 2009). Students are also exposed to theories underpinning young children's home language development so that they can understand barriers to language development and use appropriate intervention strategies (Pretorius & Machet 2004). This design takes into account the cognitive, psychological and social issues that underpin young children's language learning and which FP teachers should be familiar with, as they are expected to use the home language of learners for teaching in the FP.

Language diversity and students' identities

The third principle relates to pre-service students' identities and strategies for accommodating diversity in the FP programme as we prepare the students for the multilingual and multicultural South African context. Student teachers bring their own beliefs, experiences and personal identities, shaped by their own backgrounds (Jordaan & Pillay 2009), which influence their learning and professional development (Ashby et al 2008). The curriculum should take this into consideration, as it may determine what student teachers need to learn and how the learning process should take place (ibid).

Given the diversity of languages and cultures in South African classrooms, it is imperative that prospective teachers are exposed to the different languages in the contexts in which they are going to work. This is accommodated in the language curriculum by introducing pre-service students to a second additional language to enable them to cope with diversity and to support the teaching and learning process in their own classrooms. In fact, the policy document on minimum requirements for teacher education requires beginner teachers to have competence in a second additional language (RSA DHET 2011).

The second additional language, which caters for Afrikaans, English and isiXhosa home language speakers, is a year-long module offered in the first year of the programme. Given that English is the main medium of instruction at UWC, the emphasis in this module is on exposing students to other languages that are used in the classroom by learners. For example, Afrikaans and English home language speakers have to do isiXhosa, while isiXhosa home language speakers have to do Afrikaans as a second additional language. Having access to their future learners' home languages could assist student teachers in mediating learning in the classroom.

Early literacy development and biliteracy

Language teachers have a big role to play in developing their learners' language skills, and it is crucial that both teachers and learners have competence in more than one language (Jordaan & Pillay 2009). This view underpinned the fourth principle in the design of the FP language curriculum, as the curriculum aims to strengthen young learners' literacy skills, first in the home language, and subsequently in the first additional language, in other words, biliteracy (Honig 2014). According to Dornbrack1 (2009), learners' home language should be strengthened and developed, as it forms a solid foundation for learning additional languages. This view is echoed by Edwards (2009) in her practical and engaging book on learning to be literate in multilingual contexts. This principle is also in line with the Department of Basic Education's school-based curriculum (RSA DBE 2010), which suggests that learners should be exposed to the first additional language from Grade 1.

The curriculum is designed so as to introduce students to disciplinary knowledge in the home language from year one and in the first additional language from year two of the programme. In terms of home language literacy, the content covers various topics relating to different models and conceptualisations of literacy with regard to listening, speaking, reading and writing in the early years of schooling. Students are also introduced to barriers to early literacy development, so that they can be able to identify learners experiencing difficulties in literacy quite early.

The pre-service students are also introduced to the first additional language with regard to its structure (phonics, syntax, grammar, vocabulary, and so forth) and the ways in which young learners develop second language skills (listening, speaking reading and writing). This entails knowledge and understanding of theories underpinning first additional language learning and teaching. The content also covers young children's literature in the home language as well as the first additional language. By the end of the second year, students are expected to have an in-depth knowledge and understanding of home language and first additional language literacy development, and to know how to assist children to acquire these literacy skills (Edwards 2009; Henning & Ragpot 2014; Honig 2014).

Knowledge application and mentorship

The fifth principle isinfluenced by the notion of knowledge application and apprenticeship or mentorship (Darling-Hammond & Bransford 2005); that is, pedagogical and practical knowledge. Throughout the four years of the BEd (FP) degree, the students will be exposed to literacy teaching in the Grade R-3 classrooms, where they will be expected to observe and assist experienced teachers as they interact with young learners in language and literacy teaching. This experience will be part of practical learning, which is central to this programme, and will consist of a total of twenty-two weeks of teacher practice of varying duration spread across the four years of training. These multiple opportunities for practice and formative feedback will enable student teachers to make sense of their learning and integrate theory and practice (ibid).

Mentorship and peer support are crucial to the process of learning to teach. The context of practice should be supportive, so that students can share experiences and learn from experienced teachers (Ashby et al 2008). In this curriculum, the first two years of the programme focus on students' disciplinary knowledge of language and literacy, while the third and fourth years require them to apply this knowledge in meaningful ways in the classroom. In other words, in the third and fourth years, students will be expected to employ various strategies to design and teach lessons and assess FP literacy, and to provide adequate support to learners who experience reading and writing difficulties. They should also demonstrate an understanding of the language curriculum policy and be able to interpret it to suit the contexts in which they will be teaching. This entails integrated knowledge, which student teachers will be expected to demonstrate in modules such as Education Practice, one of the core modules of the FP programme.

Reflexivity

Finally, the concept of reflexivity in teaching (Kemmis 2011) guided the design of the FP language and literacy curriculum. Reflexivity as a teaching practice entails people observing themselves in their practice and modifying their performance in future practice (ibid). It involves identifying areas that need improvement and considering alternative strategies to transform future practice (Darling-Hammond & Bransford 2005). Reflexivity views teaching as an ongoing process with cognitive and psychological underpinnings, as it involves meaning-making and an individual's social and emotional contexts (Ashby et al 2008; Korthagen & Kessels 1999).

In the final year of the programme, the students will be expected to perform research about literacy practices in FP classrooms. They have to conceptualise and present seminar research papers based on FP literacy practices in order to display their own understanding of issues pertaining to literacy development in FP classrooms within the South African context. The aim of this taskis to stimulate students' creativity as lifelong learners and researchers in their own classrooms and to challenge them to think of appropriate strategies to improve their own teaching practice (Nomlomo 2013). It also encourages them to reinforce and synthesise concepts they have learned in their coursework and allows them to reflect on their own practice and improve their daily interaction with young learners.

To concretise the above discussion, an overview of the BEd (FP) language curriculum is provided at the end of this article (Appendix).

Implications for early literacy development: Some challenges to be expected

In presenting the rationale and principles underlying the language curriculum we have designed for FP teachers at UWC, we are acutely aware of the many challenges that will face our teachers at primary schools in the Western Cape, where many will be placed. What are some of these challenges and how do we hope to address these when offering the FP programme?

Firstly, the home languages on offer to our students are, in many respects, not 'equal'. Despite our intention of offering the same curriculum to all three language groups (Afrikaans, English and isiXhosa), the material realities imply otherwise (Msila 2011). For example, the rich literature available in English and Afrikaans is simply not available in isiXhosa. This means that isiXhosa-speaking teacher trainees will not have access to sufficient appropriate reading material in isiXhosa to excite learners about reading and the wonderful world of books. As the teacher education provider, we at UWC need to address this dilemma with our teacher trainees. One way in which we can work together is to develop new reading materials and to translate key texts into isiXhosa. In addition, we need to do an inventory of what already exists. Like their English and Afrikaans counterparts, isiXhosa-speaking learners too need to have extensive reading opportunities to develop their literacy skills. Technology such as Kindles, tablets and mobile phones can be used to assist in this regard. Student teacher assignments can be constructed around real issues, such as the lack of sufficient reading materials in African languages, so that the learning experience becomes a real one.

The question of literacy in isiXhosa assumes particular significance in view of Cummins' (1979) 'developmental interdependence' hypothesis, which postulates that the development of competence in a second language is partially a function of the type of competence already developed in the first language at the time that intensive exposure to the second language begins. In other words, the acquisition of a second language is influenced by a learner's level of development in his or her first language. Cummins suggests that differences in the ways in which children's first language has been developed by their linguistic experiences prior to school contribute to the differential outcomes of a home-school language switch in minority and majority language situations. This switch is of course very common in South Africa. The FP teacher therefore has the onerous responsibility of developing isiXhosa-speaking learners' home language literacy to an advanced level in order to allow for a transfer of knowledge and skills across languages. A pedagogical implication of this would be that teachers would need to explicitly encourage learners to transfer their first language knowledge and skills to the second language, instead of forbidding them to use their home languages, as is often the case in South African classrooms.

This is a point taken up by the West African linguist Alidou. Drawing on Cummins' (1979) theory of linguistic interdependence and its successful application in North American contexts where both the dominant language and the minority language have long traditions of literacy, Alidou raises some interesting questions about the implications of this theory for multilingual contexts such as those in sub-Saharan Africa. She argues:

This is not the case with African languages. Most are in the process of acquiring an official orthography and few publications are available in these languages. [...] The lack of literate environments in the national languages constitutes a serious barrier, preventing African children from developing adequate literacy skills in the national languages (Alidou 2004:209).

In other words, in such contexts the primary focus must be on the development of the child's mother tongue or home language. Only when a particular threshold has been reached in the mother tongue will we see the kind of transfer to a dominant language (such as English or French) that Cummins talks about. Alidou (2004:210) calls for a partnership between linguists, writers and local publishing houses to coordinate corpus planning in national languages and to encourage writing and the publication and dissemination of texts in these languages. She reminds us that libraries play a crucial role in the development of literacy in resource-poor environments, as "literacy cannot develop without a literate environment" (ibid:114). There is a high correlation between the availability of books and other educational material and academic success. Alidou cautions that:

The effectiveness of the use of African languages in education depends not only on the political and economic support of African populations, including educators and policymakers, but also on the availability of a critical mass of experts who can carry out the technical work involved in the development of effective bilingual education (Alidou 2004:213).

Given these cautionary remarks, the UWC team will also have to form partnerships with select groups of parents, as literacy practices at home determine whether children are bibliophiles or 'book-shy'. An added advantage to working with parents is that learners will not feel so estranged from the school if the language of the school is different from the language of the home.

This brings us to the next challenge. We are mindful that despite all good intentions, many teachers may end up working with learners whose home language is not the same as theirs. In such situations, extreme sensitivity is called for. The importance of the home environment for initial literacy development cannot be overemphasised in this regard (Datta 2007). We must also bear in mind that young learners often lack confidence. In addition to everything else, the FP teacher must therefore also create an environment that is supportive and enhances children's emotional well-being - a tall order indeed!

Concluding remarks

We have tried in this article to share our experiences of developing a language curriculum for pre-service student teachers in the foundation phase. As we have yet to offer the programme, we do not presently have the benefit of reflecting on how such a curriculum works in practice. However, we have tried to pre-empt some of the challenges that we will be facing in offering this curriculum to our FP student teachers. We have briefly looked at some ways of addressing these challenges, but are mindful of the human and material resource implications, particularly with regard to the development of early literacy in African languages.

References

Alidou, H. 2003. Language policies and language education in Francophone Africa: A critique and a call to action. In S. Makoni, G. Smitherman, A.F. Ball & A.K. Spears (Eds.), Black Linguistics: Language, society, and politics in Africa and the Americas. London: Routledge. 103-116. [ Links ]

Alidou, H. 2004. Medium of instruction in post-colonial Africa. In J.W. Tollefson & A.B.M. Tsui (Eds.), Medium of instruction policies: Which agenda? Whose agenda? Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. 195-214. [ Links ]

Allais, S. M. 2003. The National Qualification Framework in South Africa: A democratic project trapped in a neo-liberal paradigm? Paper presented at the Development Studies Seminar, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, 14 March 2003.

Ashby, P., Hobson, A.J., Tracey, L., Malderez, A., Tomlinson, P.D., Roper, T., Chambers, G.N. & Healy, J. 2008. Beginner Teachers' Experiences of Initial Teacher Preparation, Induction and Early Professional Development: A Review of Literature. Nottingham, UK: University of Nottingham Department for Children, Schools and Families. [ Links ]

Chisholm, L. 2004 The Quality of Primary Education in South Africa. Paper commissioned for the EFA Global Monitoring Report 2005, The Quality Imperative.

Coetzee, D. & Le Roux, A. 2007. The challenge of quality and relevance in South African education. South African Journal of Education, 21(4):208-212. [ Links ]

Cummins, J. 1979. Linguistic interdependence and the educational development of bilingual children. Review of Educational Research, 49(2):222-251. [ Links ]

Darling-Hammond, L. & Bransford, J. (Eds.). 2005. Preparing teachers for a changing world. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Datta, M. (Ed.) 2007. Bilinguality and literacy: Principles and practice. Second edition. London: Continuum. [ Links ]

Desai, Z. 2012. A case for mother tongue education? Unpublished PhD thesis. Bellville, Cape Town: University of the Western Cape. [ Links ]

Dornbrack, J. 2009. Our multilingual context: Teaching language in the South African context. In A. Ferreira (Ed.), Teaching Language. Northlands: Macmillan South Africa. 25-40. [ Links ]

Edwards, V. 2009. Learning to be literate: Multilingual perspectives. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. [ Links ]

Fitzmaurice, M. 2010. Considering teaching in higher education as a practice. Teaching in Higher Education, 15(1):45-55. [ Links ]

Foley, A. 2001. Mother Tongue Education in South Africa. Retrieved from http://englishacademy.co.za/pansalb/education.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2012).

Gamede, T. 2005. The biography of 'access' as an expression of human rights in South African education policies. Unpublished PhD thesis. Pretoria: University of Pretoria. [ Links ]

Grosser, M. & De Waal, E. 2008. Recentering the teacher: From transmitter of knowledge to mediator of learning. Education as Change, 12(2):41-57. [ Links ]

Henning, E. & Ragpot, L. 2014. Preschool children's bridge to symbolic knowledge: First literature for a learning and cognition lab at a South African university. South African Journal of Psychology. Retrieved from http://sap.sagepub.com/content/early/2014/08/12/0081246314545199 (accessed on 8 January 2015).

Hill, L.D., Baxen, J., Craig, A.T. & Namakula, H. 2012. Citizenship, social justice and evolving conceptions of access to education: Implications for research. Review of Research in Education, 36(1):239-260. [ Links ]

Honig, B. 2014. Teaching our children to read: The components of an effective, comprehensive reading program. New York: Skyhorse Publishing. [ Links ]

Jordaan, S. & Pillay, R. 2009. Beginning my journey of professional development: The language teacher and the teaching profession. In A. Ferreira (Ed.), Teaching Language. Northlands: Macmillan South Africa. 1-10. [ Links ]

Kanjee, A., Sayed, Y. & Rodriguez, D. 2010. Curriculum planning and reform in sub-Saharan Africa. Southern African Review of Education, 16(1):83-96. [ Links ]

Kemmis, S. 2011. What is professional practice? Recognizing and respecting diversity in understandings of practice. In C. Kanes (Ed.), Elaborating Professionalism: Studies in Practice and Theory. New York: Springer. 139-165. [ Links ]

Korthagen, F.A. & Kessels, J.P.A.M. 1999. Linking Theory and Practice: Changing the Pedagogy of Teachers' Education. Educational Researcher, 28(4):4-7. [ Links ]

Kwenda, C. & Robinson, M. 2010. Initial teacher education in selected Southern and East African countries: Common issues and ongoing challenges. Southern African Review of Education, 16(1):97-113. [ Links ]

Modisaotsile, B.M. 2012. The failing standard of Basic Education in South Africa. In Policy Brief, AISA (Africa Institute of South Africa), Briefing 72. 1-7.

Msila, V. 2011. "Mama does not speak that (language) to me": Indigenous languages, educational opportunity and black African preschoolers. South African Journal of Childhood Education, 1(1):48-67. [ Links ]

Murray, S. 2009. Making sense of the new curriculum: Undersatnding how the new curriculum works and what it means for language teachers. In A. Ferreira (Ed.), Teaching Language. Northlands: Macmillan South Africa. 11-24. [ Links ]

NEEDU (National Education Evaluation and Development Unit) 2012. Report on the State of Literacy Teaching and Learning in the Foundation Phase. Pretoria: NEEDU. [ Links ]

Nomlomo, V. 2013. Preparing isiXhosa Home Language teachers for the 21st century classroom: Student teachers' experiences, challenges and reflections. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies, 31(2):207-217. [ Links ]

Pendlebury, S. 2008. Meaningful access to basic education. South African Child Gauge, 2008/2009:24-29. [ Links ]

Pournara, C. 2009. Developing a new pre-service secondary Mathematics Teacher Education Programme: Principles for content selection and emergent tensions. Education as Change, 13(2):293-307. [ Links ]

Pretorius, E.J. & Machet, M.P. 2004. The socio-educational context of literacy accomplishment in disadvantaged schools: Lessons for reading in the early primary school years. Journal for Language Teaching, 38(1):45-62. [ Links ]

RSA (Republic of South Africa). 1996. Constitution of the Republic of South Africa. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

RSA DBE (South Africa. Department of Basic Education). 2010. Report of the Colloquium on Language in the Schooling System. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

RSA DBE (South Africa. Department of Basic Education). 2011. Report on the Annual National Assessment of 2011. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

RSA DBE (South Africa. Department of Basic Education). 2012. Report on the Annual National Assessment of 2012. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

RSA DHET (South Africa. Department of Higher Education and Training). 2011. National Qualifications Framework, Act 67 of 2008. Policy on the Minimum Requirements for Teacher Education Qualifications. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

RSA DHET (South Africa. Department of Higher Education and Training). 2008. National Qualifications Framework, Act 67. Draft policy on the Minimum Requirements for Teacher Education Qualifications selected from the Higher Education Qualifications Framework (HEQF). Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

RSA DoE (South Africa. Department of Education). 2005. National Curriculum Statement. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Rusznyak, L. 2009. Confronting the 'Pedagogical Immunity' of student teachers. Education as Change, 13(2):263-276. [ Links ]

Sayed, Y. & Motala, S. 2012. Getting in and staying there: Exclusion and inclusion in South African schools. Southern African Review of Education, 18(2):105-118. [ Links ]

Shrum, J.L. & Glisan, E.W. (Eds.) 2000. Teacher's Handbook - Contextualized language instruction. Second edition. Boston, MA: Heinle Publishers. [ Links ]

Whitehead, M. 2007. Developing language and literacy with young children. Third edition. London: Paul Chapman. [ Links ]

Whitehead, M. 2009. Supporting language and literacy development in the early years. Second edition. Maidenhead: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Whitelaw, S., De Beer, J. & Henning, E. 2008. New Teachers in a Pseudocommunity of Practitioners. Education as Change, 12(2):25-40. [ Links ]

* Email: vnomlomo@uwc.ac.za

1. First Additional Language is also referred to as ‘second language’ in the literature; hence the two terms are used interchangeably in this article.

APPENDIX

Overview of the BEd (FP) Language/Literacy curriculum