Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Childhood Education

On-line version ISSN 2223-7682

Print version ISSN 2223-7674

SAJCE vol.4 n.2 Johannesburg 2014

ARTICLES

Biography, policy and language teaching practices in a multilingual context: Early childhood classrooms in Mauritius

Aruna Ankiah-GangadeenI; Michael Anthony SamuelII

IMauritius Institute of Education. Email: a.ankiah@mieonline.org

IIUniversity of KwaZulu Natal

ABSTRACT

Language policies in education in multilingual postcolonial contexts are often driven by ideological considerations more veered towards socio-economic and political viability for the country than towards the practicality at implementation level. Centuries after the advent of colonisation, when culturally and linguistically homogenous countries helped to maintain the dominion of colonisers, the English language still has a stronghold in numerous countries due to the material rewards it offers. How then are the diversity of languages - often with different statuses and functions in society - reconciled in the teaching and learning process? How do teachers deal with the intricacies that are generated within a situation where children are taught in a language that is foreign to them? This paper is based on a study involving pre-primary teachers in Mauritius, a developing multilingual African country. The aim was to understand how their approach to the teaching of English was shaped by their biographical experiences of learning the language. The narrative inquiry methodology offered rich possibilities to foray into these experiences, including the manifestations of negotiating their classroom pedagogy in relation to their own personal historical biographies of language teaching and learning, the policy environment, and the pragmatic classroom specificities of diverse, multilingual learners. These insights become resources for early childhood education and teacher development in multilingual contexts caught within the tensions between language policy and pedagogy.

Keywords: biographical experiences of learning English, multilingual context, language policy, pedagogical practices in ECE

Introduction

Teaching languages in a multilingual context is rarely a simple process, especially when the medium of instruction and the most prominent language in the curriculum is the first language of neither the teacher nor the students. The problem can be exacerbated when educational policies regarding language, which are closely related to the aspirations of developing postcolonial nations, appear viable and sound from economic and political perspectives but may be problematic at the level of implementation. Inevitably, it is teachers who transact these decisions in the classroom that have to grapple with the intricacies of interpreting policy and putting these into practice. Paradoxically, the experiences of these teachers are inadequately documented and there is little attempt to understand the influences that shape their pedagogy. This is more apparent in developing African countries, like Mauritius, that harbour a number of languages as a legacy of their colonial past and where there is a constant tug between native languages and a foreign Western language of instruction, generally English. The complex situations that arise from conflictual relationships between home languages and languages bearing capital promoted by policy - especially with respect to education - are widely discussed in the literature (Bruthiaux 2002; Chimbutane 2011; Mashiya 2011; Msila 2011; Smitherman 2004). It must nevertheless be pointed out that language policies are not problematic solely in postcolonial societies. Paris (2012:95), for instance, decries the way in which English-only policies in the United States deliberately promote "a monocultural and monolingual society based on White, middle-class norms of language and cultural being" to the detriment of the diversity of communities in the pluralistic American society.

This paper emanates from a doctoral study conducted at pre-primary level in Mauritius. The aim was to gain an understanding of the way in which the biographical experiences of teachers impacted upon their approach to the teaching of English and to identify the main factors that shaped their pedagogy. Our endeavour was to hear the voices of the teachers in order to understand, from their perspective, the intricate process whereby their pedagogical practices developed in a multilingual context.

Background

Our focus on the teaching of the English language is due to it being the language of administration as well as the medium of instruction in Mauritius, despite not being the first language of the majority of Mauritians (see Appendix I). Though there is leeway to use the children's mother tongue in the early years of schooling, according to the Education Ordinance (1957), which still governs the educational system, English is viewed as being of such significance in this sphere that it is taught right from pre-primary level. Moreover, a pass in this subject at School Certificate and Higher Certificate1 levels is mandatory. The uncritical acceptance that the hegemonic force of the exit target of schooling should be competence in English prompts one to wonder whether this edifice is being adequately scaffolded from foundational levels in the early years when English is not the dominantly understood or experienced language of many early school-going learners. Our decision to examine the teaching of English at pre-primary level was motivated by the fact that the early years are crucial for the child's development (Menyuk & Brisk 2005; Ritblatt, Garrity, Longstreth, Hokoda & Potter 2013; Roberts & Neal 2004; Weikart 2000; Wortham 2006) and that language plays a significant role in that process. Additionally, it was our conviction that language choices are shaped in the initial years and that the early schooling experiences of children, to a great extent, determine their proficiency as well as their attitude towards particular languages.

In the local context, however, a striking shortcoming in the pre-primary National Curriculum Framework (NCF) is that it presents a single curriculum and set of descriptors for all languages taught. In doing so, the NCF overlooks the learners' and teachers' multilingual profile. It fails to acknowledge that, in such a context, both the teachers' and learners' mother tongues and their mastery of different languages are bound to vary. It expects pre-primary teachers to display an equal degree of fluency in all languages taught in order to act as models and, similarly, it expects the language learners to attain the same level of proficiency in all languages. It fails to consider the degree to which the lowly qualified pre-primary teachers (Ministry of Education, Arts and Culture 1991; Ministry of Education, Science and Technology 1996; Ministry of Education, Culture and Human Resources 2008), often with limited fluency in English, are capable of enacting the curriculum. This inevitably places the teachers at the interface between policy and practice, having to mediate a curriculum they may not be equipped to implement in a classroom comprised of learners with varied linguistic profiles. Thus, while at the macro level broad policy strokes emanating from the Jomtien Conference and Dakar Framework for Action (2000) established expected outcomes, at the micro level there is no enabling framework that supports the teachers in achieving these outcomes. As Mattson and Harley (2003:285) argue, "the danger inherent in policy-making is that it can effortlessly reconcile on paper what cannot be reconciled in practice". Consequently, "policy on teachers' roles and competencies [is] out of step not only with teachers' professional identities but also with their personal and cultural identities" (ibid:287). When applied to the Mauritian context, the position adopted by the NCF betrays a lack of consideration for the reality of contexts as well as the relationship between different languages. In fact, this stance flouts the stated prerequisites for the successful implementation of education programmes, namely:

[...] a relevant curriculum that can be taught and learned in a local language and builds upon the knowledge and experience of the teachers and learners.

(Dakar Framework for Action, 2000:np)

The discrepancy between what is expected and what is feasible triggers the following questions, which formed the crux of our study: How do teachers with varied linguistic profiles reconcile policy and practice? How do they "negotiate the tensions and contradictions sidestepped by the policy in their day-to-day classroom practice" (Mattson & Harley 2003:286)? To what extent do they espouse and enact the curriculum? What teaching approaches do they opt for in teaching English? What guides them in their choice of approach?

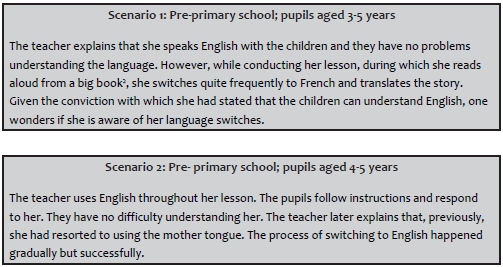

With the onus to manage the diversity of languages in the classroom being put on the teacher, it is not surprising that different scenarios of language use and teaching can be observed, as revealed by the vignettes below.

These glimpses into two classrooms not only foreground the variation in language use, but also highlight the teachers' agentic potential in establishing this variation. Thus, in order to gain an insight into the factors that influenced the way in which teachers present the English language to their learners, it was deemed necessary to probe into their lives and understand how their biographical experiences of learning English shape their conceptions of language and hence their pedagogy. The researchers were keen to establish why teachers choose the kinds of strategies they do to engage with the teaching of English.

Research methodology

The endeavour to discover multiple truths prompted us to opt for life history research, which allows participants to shape and relate their stories, as the emphasis is on the participants' interpretation of what they have lived. These stories are, however, not mere renderings of lives as a series of events, but rather of lives that have been interpreted and made textual (Goodson & Sikes 2001). As Sosulski, Buchanan and Donnell assert:

Life story techniques introduce the opportunity to collect rich data textured by respondents' own interpretations of their experiences and the social circumstances in which their story has unfolded, and the ways in which they continue to be active agents.

(2010:37).

With subjectivity and positionality being privileged (Riessman 2000), the focus, then, is not on the events themselves, but on the participants' understandings of these events (Kouritzin 2000). Since our focus was on the participants' personal experiences of language learning and their conceptions of English, this approach was propitious to a better understanding of the pedagogical orientation of individual teachers.

Narrative inquiry was chosen as the research methodology in order to generate rich data on the phenomenon being studied. Combining life history with narrative inquiry became an obvious choice because, as stated by Hatch and Wisniewski,

Understanding individual lives or individual stories is central to the research process and products of life history and narrative [...] Individual lives are the unit of analysis of life history work and individual stories are the stuff of narrative analysis.

(1995:116).

Narrative inquiry captures the dialectical relationship between individuals, spaces or contexts, and time, and thereby affords a better insight into the deeply textured and complex process of identity development. Given the situatedness or embeddedness of knowledge construction, it is essential for researchers exploring teachers' knowings to foreground the context. It was therefore premised that insight into teachers' "personal practical knowledge" (Clandinin & Connelly 2000:3) would best be understood in the light of their biographic experiences since "their teaching is grounded in their personal resources, values, and life experiences" (Elbaz-Luwisch 2007:364). Here, too, narrative inquiry finds its relevance, as it enables the storyteller (be it the researcher and/or the 'researched') to situate the chain of events and formulate insights with respect to the complex chronicle of events that constitutes life (ibid; Pinnegar & Daynes 2007; Stephens & Trahar 2012).

Narrative inquiry prizes individual voices, as explained by Andrews:

"Stories do not come out of nowhere, nor do they simply represent experience or an event as it actually happened. Rather they are always a representation of that, and as such are a very rich means for accessing inner truths, those ideas, beliefs and commitments which an individual holds dear."

(2012:34).

The chosen methodology would thus allow the participants to retain their individuality, as "human actions are unique" (Polkinghorne 1995:7) and experiences subjective. This epistemological position linked up effectively with the interpretivist research paradigm within which the study was situated.

Participants and data production tools

Six pre-primary school teachers were involved in the study: Sandy, Preety, Jyotee, Mala, Chantal and Francine. They presented an interesting variation in terms of age group, number of years of experience, school context and the profile of their learners - all factors that are deemed to impact significantly on one's language teaching approach. As life history research thrives on representing "subjectively meaningful experiences through time" (Hitchcock & Hughes 2003:185), the participants brought with them a diversity of biographical experiences that added to the richness of the data.

All the participants were women as, in Mauritius, all pre-primary teachers are women. They had between 2 and 30 years of teaching experience in the pre-primary sector. They were, at the time of the study, working at private or government schools located in both rural and urban areas. It must be pointed out that, given the small size of the island, rural and urban areas are proximate in Mauritius and the rural/urban variations or schisms regarding language use in bigger countries are not necessarily valid. Forinstance, prestigious English- or French-medium private pre-primary schools located in rural areas admit children who come from around the island and whose parents can afford to send them there. On the other hand, some schools in urban areas are attended by Creole-speaking children, mostly of low socio-economic status, because of the mother-tongue policy. The profile of the school emerged as an interesting factor with respect to the issue of language and social class, and we were interested in understanding how far these factors determined the pedagogical practices of the teachers. The participant and school profile sheet in Appendix II provides an overview of the selected participants and their locations.3

Data generation lasted six months and the following tools were employed: informal biographic interviews where the participants were encouraged to share their experiences of language use and language learning from childhood to date; classroom observations for insight into their teaching practices; informal conversations to clarify any point or seek additional information; photographs to trigger memory; and artefacts to shed further light on teaching practices and language use. Learners' worksheets; letters from parents to one of the teachers; testimonials from heads or inspectors; a teacher's form for the Pay Research Bureau4 containing details pertaining to her responsibilities; a PowerPoint presentation of a teacher's pedagogical approach, which had been used during a workshop with colleagues; a teacher's visual representation of her metaphor to represent her self as a teacher; and the National Curriculum Framework pre-primary and/or the teaching programme being implemented, which varied in private schools, also offered useful additional data regarding language learning and teaching. While the interviews, observations and informal conversations were systematically carried out in all cases, the artefacts varied according to what the teachers found to be significant and felt inclined to bring. No pressure was exerted on them, as this was considered to be unethical. The choice of tools was guided by the need to delve into the human experience, which, according to Polkinghorne (2005), is a difficult area to study, given its multilayered and complex nature. Moreover, it was deemed that visual data, such as photographs, was an effective means of bringing an element of reflexivity (Mitchell 2011) into the research process, with participants actively engaged in interpreting their past experiences.

Findings

Researchers based in developing countries with limited research output are often compelled to rely on foreign literature, which does not always shed much light on phenomena in dissimilar contexts. The use of life history research in this study foregrounded a number of contextual features that impacted upon the development of teachers' conceptions and the teaching of English.

Home influences on language pedagogy

An interesting revelation that emerged from the study was the power of informal language experiences to shape the way the teachers conceived of particular languages. The informal experiences of the participants were in fact seen to be as telling as formal experiences, and turned out to be the feature that impacted most significantly on them. Early experiences of language use in the home stood out as the determining factor in eventual language choices and preferred languages. Budding notions of language emanated from the home environment and were reinforced in the later years. For instance, Sandy's parents encouraged her to learn English, but looked down on Creole. And as it was reinforced in the schools she had attended, this attitude was duly instilled in her. On the other hand, Chantal's and Mala's parents never consciously exerted a push towards learning English - both these participants therefore grew up operating in French/Creole and Creole only environments respectively, encountering English only in an academic setting. As opposed to Sandy, who made a concession when she used Creole in the classroom, Chantal and Mala staunchly acknowledged the need to prize the child's first language.

The findings also highlighted the fact that the lived language experiences of the teachers had frequently taught them more about pedagogy than what had been formally advocated. Enlightened by their own experiences as learners (of rejection and alienation in the classroom, but also of fascinating and innovative English teachers and lessons), the teachers espoused a teaching philosophy that was child-friendly and adopted an approach that was inclusive. Their concern for making the child feel included overshadowed purely academic considerations. Mala's case was an apt illustration of this fact. She was raised in a home where she did not feel the need to speak English or French, these languages being of no import in her immediate environment. Due to her lack of proficiency (she could neither understand nor communicate in these languages), Mala felt isolated in the classroom. Moreover, the teacher-centred approaches that had prevailed during her schooling and pushed students to passive roles reinforced her position as an outsider. She described the effect this had on her as follows:

My lack of confidence has resulted in an innate fear that makes me apprehensive about what the teacher will say, the language he will use and the way he will talk to me. I can only communicate partly in English as I end up being lost for words.

(Extract from Mala's narrative)

This justifies her stance:

Compelling children to speak English is not a good way to teach them. The children must express themselves in their mother tongue - be it Creole, English or French. When the children have just left home to join preschool, they are like newborn babies who have just entered a new world. It is crucial to avoid creating an abrupt disruption in their lives. Teaching children demands a different approach. If we teach the children another language at this point, it becomes too difficult for them to learn it. But if we speak their mother tongue, the children are happy and blossom. They feel close to us and tell us whatever is on their mind. This is something they wouldn't have been able to do if they had to use another language.

(Extract from Mala's narrative)

English as capital

The study further revealed that one's socio-economic and ethnic background, by influencing the choice and purposes of the language(s) that one uses, shapes one's conceptions of languages and budding pedagogical ideology. The participants evolved in a multilingual setting that promoted exposure to and the use of diverse languages. However, the language(s) in which participants had been socialised5 from an early age, in the home, had a dominant influence on the way that they grew to use and perceive different languages. Their linguistic creed was shaped by home experiences and, in later years, they displayed more sensitivity towards influences that reinforced these notions about language use. Thus, if, irrespective of their level of proficiency in English, all participants acknowledged the need to master this language, the degree to which and the way in which it was used in the classroom varied. Participants who had experienced an overt push towards English as linguistic and/or cultural capital - forinstance, due to parental influence - displayed particular appreciation of teachers who used communicative and child-centred approaches to teaching it, as this had enabled them to be fully involved in the lessons and appreciate the language. Not only did they strive to learn the language, but eventually, as teachers, they saw the need to make their learners communicate more extensively in English. On the other hand, in cases where English had been absent or less prominent in the home, participants were more struck by the feeling of alienation they had felt as learners because they had been unable to understand and communicate in that medium, and hence, participate in the lesson. These participants were eventually seen to emphasise on the value of the mother tongue. As their lack of proficiency had severely hampered their ability to understand and communicate in English, making them outsiders in their own classrooms, they displayed added sensitivity to the predicament of their learners and a willingness to accommodate the children's mother tongue in the learning process. Pedagogical choices are thus closely derived from one's language experiences in the home.

Local anchorage/global outlook

An interesting finding relates to the 'local anchorage/global outlook' concept, which adds fuel to the local/global debate by drawing attention to the limited notions of language use and pedagogy that may result from the adoption of too restrictive an outlook by focusing exclusively on the here and now. In small island contexts, individuals who have not experienced the use (hence, utility) of the English language in their everyday life may be prone to harbouring a myopic vision of language policies with respect to that language. The need to master an international language becomes more meaningful if one has the opportunity to experience its use in real life or authentic situations, either by being in a foreign land or by interacting with people who have done a stint abroad. Failing such experiences, the insularity of the place may lead to a restrictive view of the use of the English language and the way in which it should be taught. The narratives revealed a consistent pattern regarding the impact of 'foreign contact' on the participants' learning and teaching of English. Such contact was seen to open up avenues for participants to recognise the communicative and cultural aspects of the English language and even to identify the communicative approach to teaching language as being most beneficial to learners. It emerges that the positive ramifications of such contact may lead to the adoption of a more global outlook and a different conception of the language taught. The discourse of the participants who had experienced a 'foreign brush' - either through time spent abroad, or interaction with foreigners or people who had lived abroad - contrasted sharply with that of those who had not. For instance, while Sandy, who had had British teachers and had spent time in Australia, equipped her students with basic vocabulary and used English predominantly, Mala, who had had no foreign experience, was of the view that it was more important to communicate in the child's first language and that English would be learnt at primary school.

Interpretation: Teachers chart the navigation map

Since narrative inquiry probes into the different spheres of life, it proved a significant tool for theorising teachers' developing conceptions of language and their practice in a multilingual country. In contexts with a multiplicity of languages, teachers grow to understand and appreciate the value and functions of different languages - cultural, functional, communicative, academic, economic, affective and so on - and of language teaching approaches from their biographical experiences as language users, learners and teachers. Their conceptions of language and teaching are shaped by their:

- Socio-economic background, which influences language choices in their home and environment and their impetus to learn English;

- Ethnic background, which predisposes individuals towards predominant languages they are exposed to or in which they interact with family members and relatives;

- Schooling experiences, whereby, being at the receiving end of various language teaching methods, they are able to gauge the effectiveness or influence of these;

- Apprenticeship experiences as trainees, where they observe language pedagogy in practice and its effect on learners;

- Professional experiences as teachers, where they constantly strive to meet the needs of their learners while attempting to attain programmatic targets.

The above-mentioned factors do not act in isolation. The fuzzy boundaries of language use cause them to act in conjunction with one another and thereby shape teachers' beliefs. It should be noted that these factors are themselves shifting in nature and subject to change when triggered by micro or macro forces. The teachers' belief system is thus in constant motion and evolves accordingly.

The paradox within which teachers, as those in Mauritius, operate was highlighted earlier: they have to teach and promote the use of a language that is neither their own mother tongue nor that of the majority of their learners and which is hardly used in everyday life. Additionally, they have to operate amidst a number of considerations: policy guidelines and requirements, learners' needs and level, as well as programmatic concerns, both at school and national levels. In such circumstances, as the study revealed, teachers adopt a pragmatic approach to reconcile the two odds, that is, maintaining communication with learners while teaching a second/foreign language. Driven by their own experiences as language learners, teachers understand the need to include learners in the instructional process. The pedagogy of the participants was based on affective considerations, as they placed their learners at the centre of their decisions. The extent to which the English language is spoken (as opposed to French and Creole) and the way in which it is taught (through a communicative or audio-lingual approach) are thus mostly dependent on what they perceive their learners' profile to be, namely their background and mother tongue.

However, the teachers' underlying notion of the need to develop their learners' fluency in English also plays an important role. The extent to which they uphold this notion is derived from early 'messages' about the English language in the home and their own motivation to learn it. English language teaching in a multilingual space is an extension of the teachers' selves, as it embodies both their beliefs about language and their pedagogical ideologies. However, they do not strive to reach their objective at the expense of their learners' communicative ability. A pedagogical approach that is based on affective considerations ensures that their dual goal of teaching English and involving their learners in the process is achieved. This explains why different classrooms reflect diverse teaching approaches and uses of English.

The teachers within this sampled context, therefore, do not indulge in the "strategy of mimicry" (Mattson & Harley 2003:297), of pandering superficially to the policy expectations, nor do they blindly adhere to established curricula; their pedagogical practices are based on conscious choices forged by their pedagogical ideology, the foundation of which was laid in their own biographical experiences. Adopting an operational stance, teachers take programmatic and instructional decisions with respect to the profile and perceived needs of their learners - even if this entails the rejection (fully or partially) of programmes that are imposed from the 'top'. Teachers interpret the curriculum and evaluate its feasibility with their learners in mind. They appropriate it in a way that they believe will work for their learners. This explains why the programmatic force varies in different classrooms.

The study revealed that teachers' professional development undergoes a movement from practice to theory. Much of what they experience is more credible to them as they are able to derive in situ - in both formal and informal contexts, and from the perspective of a learner, trainee or teacher - the do's and don'ts of language teaching. Their apprenticeship or development is ongoing and spans various spheres and periods of their lives: they learn about effective methods from their roles as learners in the home and the school, as observers during internship, and as practitioners. With teachers, 'seeing is believing': the experiential weighs more than what may be espoused by policy makers, academics, researchers or theorists. This dualistic stance is seen in the way teachers refute the same theories when these are advocated if they deem these theories not to meet their learners' needs. In this respect, the teachers' pedagogy is innately dynamic and constantly being readapted in line with new understandings of teaching and attempts to tailor it to their students' profile.

In direct contrast to the above, we also note that the manner in which teachers negotiate the various influences and interpret their language experiences is imbued with subjectivity. The teachers rely on their personal experiences of language learning and teaching and their perceived knowledge of their learners to make pedagogical decisions. The centrality of their learners in the decision-making process originates from their own harsher and/or more supportive biographic language experiences in their homes, schools and communities. However, while they seek to protect their learners and create a safe environment - arguably a prerequisite for learning - they run the risk of pathologising their learners by projecting their selves onto them and, hence, of limiting rather than opening up possibilities to learn the target language. In failing to maintain a critical distance between their experiences and their learners, teachers fall into the trap of exercising the tyranny of care, as being too caring may be to the detriment of the intellect (Amin 2011). The drawbacks of teachers' knowings thereby become evident - more so when they indiscriminately reject established educational theories only to adopt them if these same theories emanate from their personal biographies. This over-reliance on their personal lived experiences is indicative of the dangers of adopting too narrow an outlook and, thus, of the need for teachers to be more reflexive in relation to their biographic understandings.

Implications for teacher education

The findings of the study have significant implications for teacher education bodies. The study reveals that teachers come to teacher education programmes (TEPs) already equipped with rich experiences that inform their understanding of their role as teachers and the teaching process. However, this is often not embraced as a resource for affirmation and/or contestation in the process of professional learning and development. Ironically, the acknowledgement of learners' heritage of experiences is often the overt propositional stance that teacher educators argue prospective teachers should adopt when working with learners, yet teacher educators themselves often do not practice what they preach with their students. Teacher education is often experienced as an imposition of preferred theoretical roles and identities onto student teachers and even, at times, as irrelevant to the classroom reality. We propose that teacher development courses should aim to build on teachers' understandings, instead of brushing them aside in order to establish new theoretical bases. Prospective and in-service teachers work towards their knowings on the basis of their personal experiences, drawn from their personal biographical localities. Prior to introducing them to 'new' knowledge, it is necessary to understand where and how they are positioned. The effectiveness of TEPs lies in the way in which they are made to articulate with teachers' prior knowledge. The lesson that teacher educators can learn from teachers is to align teaching to the profile of learners in order to enhance its effectiveness. While teacher educators have rich theoretical understandings, teachers possess a wealth of practical knowledge. Teacher development is to be conceived of more as a partnership between teachers and teacher educators, because grounding TEPs in contextual realities will enhance chances to reconcile theory and practice. By acknowledging and considering the teachers' knowledge of the context and of learners, teacher educators make their way towards a better understanding of those whose education they seek to enhance. Moreover, the study reveals that the traditional dichotomies between a purely 'theory-less' practice, arising from the context of lived school classrooms, and a purely non-practical university teacher education programme are caricatures of the complexities of teaching and teacher development. Both the worlds of teacher education and teaching in school contexts offer abundant resources for theory and practice.

Conclusion

Reconciling policy and practice is no easy feat, especially when weak mechanisms hamper policy implementation. The study undertaken showed how teachers' biographical language experiences empower them to make strategic choices with respect to the teaching of English in a multilingual context. As reflexive practitioners, teachers draw on their own experiences of language learning to devise a pedagogical approach that places the child at the centre of their teaching. Nevertheless, when hazy policy guidelines put the onus for implementing these policies largely on teachers, the subjectivity of their experiences may undercut their beliefs about teaching - more so when they identify too closely with their learners - and be to the detriment of learning. The use of the life history approach allowed us to explore the deeply layered biographical experiences of our participants to reveal that language teaching is not a mere matter of theory application but, rather, that teachers engage in an ongoing process of personal theory construction. By delving into the very messiness of life to examine the dialogical and at times dissonant relationships between the various factors influencing language learning, language conception and language pedagogy, we were able to understand how ECE teachers translate policy into classroom practice without undermining the home language - and, one may argue, the affective needs of their learners. The insight into how teachers in a multilingual context construct their language teaching practices suggests a need to rethink teacher education so that teachers' knowings are acknowledged and mined in order to create more coherence between TEPs and classroom reality.

References

Amin N. 2011. Critique and care in higher education assessment: From binary opposition to Mobius congruity. Alternation, 18(2):268-288. [Retrieved 13 November 2013] http://food.ukzn.ac.za/. [ Links ]

Andrews M. 2012. Learning from stories, stories of learning. In: I Goodson, A Loveless & D Stephens (eds). Explorations in narrative research, Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. 33-41. [ Links ]

Bruthiaux P. 2002. Hold your courses: language education, language choice, and economic development. TESOL Quarterly, 36(3):275-296. [ Links ]

Chimbutane F. 2011. Rethinking bilingual education in postcolonial contexts. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. [ Links ]

Clandinin DJ & Connelly FM. 2000. Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Colony of Mauritius. The Education Ordinance. 1957. A collection of ordinances, proclamations and government notices published during the year 1957. Port Louis: J Eliel Felix, ISO, Government Printer. [ Links ]

Dakar Framework for Action. 2000. Education for all: Meeting our collective commitments. Dakar, Senegal, 26-28 April 2000. [Retrieved 9 May 2013] http://www.unesco.org/education/wef/en-leadup/dakfram.shtm.

Elbaz-Luwisch F. 2007. Studying teachers' lives and experience. In: DJ Clandinin (ed). Handbook of narrative inquiry: Mapping methodology. 357-382. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Goodson I & Sikes P. 2001. Life history research in educational settings: Learning from lives. Philadelphia, PA: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Hatch JA & Wisnewski R. 1995. Life history and narrative: Questions, issues and exemplary works. In: JA Hatch & R Wisnewski (eds). Life history and narrative. London & Washington, DC: The Falmer Press. 113-135. [ Links ]

Hitchcock G & Hughes D. 2003. Research and the teacher: A qualitative introduction to school-based research. London and New York: Routledge Falmer. [ Links ]

Kouritzin SG. 2000. Bringing life to research: Life history research and ESL. TESL Canada, 17(2):1-35. [ Links ]

Mashiya N. 2011. IsiZulu and English in KwaZulu-Natal rural schools: How teachers fear failure and opt for English. South African Journal of Childhood Education, 1(1):19-31. [ Links ]

Mattson E & Harley K. 2003. Teacher identities and strategic mimicry in the policy/ practice gap. In: K Lewin, M Samuel & Y Sayed (eds). Changing patterns of teacher education in South Africa: Policy, practice and prospects. Cape Town: Heinemann. 284-305. [ Links ]

Menyuk P & Brisk ME. 2005. Language education and development: Children with varying language experiences. Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Ministry of Education, Arts and Culture. 1991. Education Masterplan for the Year 2000. Mauritius.

Ministry of Education, Culture and Human Resources. 2008. Draft Education and Human Resources Strategy Plan (2008-2020) Mauritius. Mauritius.

Ministry of Education, Science and Technology. 1996. Policy on Educational Reforms. Mauritius.

Mitchell C. 2011. Doing visual research. London & New York: Sage. [ Links ]

Msila V. 2011. "Mama does not speak that (language) to me" - Indigenous languages, educational opportunity and Black African preschoolers. South African Journal of Childhood Education, 1(1):48-67. [ Links ]

Paris D. 2012. Culturally sustaining pedagogy: a needed change in stance, terminology, and practice. Educational Researcher, 41(3):93-97. [Retrieved 23 September 2014] http://er.aera.net. [ Links ]

Pinnegar S & Daynes JG. 2007. Locating narrative inquiry historically: Thematics in the turn to narrative. In: DJ Clandinin (ed). Handbook of narrative inquiry: Mapping methodology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. 3-34. [ Links ]

Polkinghorne DE. 1995. Narrative configuration in qualitative analysis. In: JA Hatch & R Wisnewski (eds). Life history and narrative. London & Washington, DC: The Falmer Press. 7-23. [ Links ]

Polkinghorne DE. 2005. Language and meaning: Data collection in qualitative research. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(2):137-145. [ Links ]

Riessman CK. 2000. Analysis of personal narratives. [Retrieved 21 September 2013] http://alumni.media.mit.edu/-brooks/storybiz/riessman.pdf.

Ritblatt SN, Garrity S, Longstreth S, Hokoda A & Potter N. 2013. Early care and education matters: A conceptual model for early childhood teacher preparation integrating the key constructs of knowledge, reflection and practice. Journal of Early Childhood Education, 34:46-62. [ Links ]

Roberts T & Neal H. 2004. Relationships among preschool English language learners' oral proficiency in English, instructional experience and literacy development. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 29:283-311. [ Links ]

Smitherman G. 2004. Language and African Americans: Movin on up a Lil Higher. Journal of English Linguistics, 32(3):186-196. [Retrieved 23 September 2014] eng.sagepub.com. [ Links ]

Sosulski MR, Butchanan NT & Donnell CM. 2010. Life history and narrative analysis: Feminist methodologies contextualising black women's experiences with severe mental illness. Journal of Sociology and Mental Welfare, 37(3):29-57. [ Links ]

Stephens D & Trahar S. 2012. Just because I'm from Africa, they'll think I'll want to do narrative. In: IF Goodson, AM Loveless & D Stephens (eds). Explorations in narrative research. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. 59-69. [ Links ]

Weikart DP. 2000. Early childhood: need and opportunity. Fundamentals of Educational Planning Series No 65. Paris: UNESCO. [ Links ]

Wortham SC. 2006. Early childhood curriculum: Developmental bases for learning and teaching. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Zhang H. 2010. Cultivating an inclusive individuality: Critical reflections on the idea of quality education in contemporary China. Frontiers of Education in China, 5(2):222-237. [ Links ]

1. The School Certificate and Higher School Certificate are examinations conducted by the University of Cambridge, UK, which Mauritian students take at the end of the fifth and seventh year of secondary schooling, respectively.

2. An enlarged storybook for children with large print and colourful illustrations.

3. Pseudonyms have been used in order to protect the anonymity of the contexts and participants.

4. The Pay Research Bureau (PRB) reviews the pay, grading structures and conditions of service in the public sector.

5. The term 'socialised into language use' here refers to the explicit or implicit 'push' towards particular languages given their predominance as language(s) of the environment or because they stand as cultural capital.

6. The Early Childhood Care and Education Authority, which oversees the running of pre-primary schools.

7. BEC: "[T]he executive office of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Port-Louis for its education services [... It] coordinates the administration of the primary RCA schools and the main policy directions of the catholic secondary schools with the collaboration of the other congregations". (http://www.bec-mauritius.org/bureau)