Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Childhood Education

versión On-line ISSN 2223-7682

versión impresa ISSN 2223-7674

SAJCE vol.4 no.2 Johannesburg 2014

ARTICLES

What challenges do foundation phase teachers experience when teaching writing in rural multigrade classes?

Janet CondyI; Bernita BleaseII

ICape Peninsula University of Technology. Email: condyj@cput.ac.za

IICape Peninsula University of Technology

ABSTRACT

A one-size-fits-all curriculum cannot address the issues faced by rural multigrade teachers and learners. In South Africa, despite government efforts to relieve adversity, poverty in rural areas is still rife and poor education still fails to lift people out of it (Joubert 2010). Equality is essential in ensuring that all South African children have access to quality education where they can learn in an environment free from bias and discrimination (Asmal 2001). Bronfenbrenner's social ecological systems theory underpinned this study. The purpose of this research was to identify the challenges experienced by two foundation phase teachers in teaching writing. This research was a qualitative study embedded within an interpretive case study. The following factors became evident: poor socio-economic backgrounds, transport, parental illiteracy, and teacher challenges that include the following subthemes: reading problems, differentiated teaching, resources, the language of teaching and learning, and writing support from the Western Cape Education Department (WCED).

Keywords: rural, multigrade, writing, challenges, quintile, pedagogies

Introduction

The research topic of this studyincludes the following three concepts: 'rural', 'multigrade', and 'the challenges of writing practices'. It was difficult to locate current internationally published literature that combines all three of these concepts. In the past few years, however, there have been a few local conferences, attended by international researchers, on multigrade education in Cape Town, and it was possible to draw on papers presented at these conferences which focused on 'rural' and 'multigrade' education. In contrast, there are many more books and articles published in the field of general 'writing practices' in urban monograde settings.

Research shows that South Africa needsits own, 'indigenous' solutions to indigenous problems arising from curriculum development. Importing an alien system such as Outcomes-Based Education (OBE) fails to account for, let alone address, the complexity of our country and its culture (Macintosh 2003). A one-size-fits-all curriculum cannot address the issues that rural multigrade teachers and learners face. This is the first study of its nature and could play an important role in recommending solutions to problems identified in the research.

The National Curriculum Statement (NCS) (RSA DoE 2001b) states that the curriculum seeks to create critical and active citizens, lifelong learners who are confident, independent, literate, multi-skilled and compassionate in society. Teachers are encouraged to inspire children with values based on respect, democracy, equality, human dignity and social justice. However, teachers and learners, in rural multigrade classes face challenges that hinder their ability to reach the literacy goals required by the NCS.

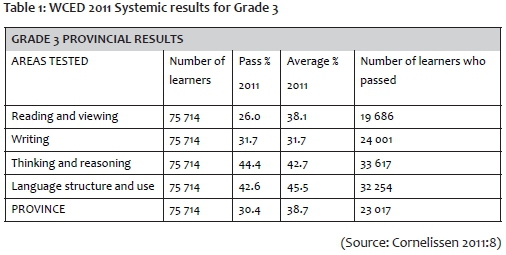

In 2011, the Western Cape Education Department (WCED) conducted the Western Cape Systemic Tests. Table 1 shows the provincial literacy results of Grade 3 learners.

Although the WCED has implemented a Literacy and Numeracy (LITNUM) Strategy for 2006 to 2016 (WCED 2006), these results indicate that writing remains an area of weakness in a national schooling system that leaves much to be desired:

Schooling in South Africa is a national disaster. The vast majority of our schools are simply not producing the outcomes that are their chief objective. What is more, international tests suggest that South African schools are among the world's worst performers in maths and literacy. Worse still is the tragedy that our schools are reinforcing the social and economic marginalisation of the poor and vulnerable.

(Bloch 2009:58)

Countries such as Columbia, India, the Netherlands, Greece and Australia also have to deal with discrepancies in learners' achievement levels and have developed programmes, curricula, resources and strategies to address educational issues in a multigrade setting (Aghazadeh 2010; Berry & Little 2007; Cornish 2010; Joubert 2010; Padmanabha Rao & Rama 2010; Tsolakidis 2010; Vithanapathirana 2010).

Literature review

Since this study focuses on rural multigrade foundation phase teachers' challenges while teaching writing skills, three components have informed the structure of the literature review, namely a discussion on rural multigrade teaching, followed by what constitutes writing skills in a foundation phase class, and finally some possible writing challenges.

Multigrade education is a way of life for most rural communities and constitutes a shift from teacher support to group support, peer support and, ultimately, individual self-directed learning (Mulryan-Kyne 2007). Far from being an impediment to learning, multigrade teaching may be a benefit to the country. This ideology is in line with the development of writing itself. More significantly, Little (2005) finds that friendship patterns, self-esteem, and cognitive and social development are more favourable in multigrade schools. Multigrade classrooms are consequently ideal, as teachers guide children and children guide their peers towards their own independent learning and writing.

Taylor (2008) states that, despite the insults and discrimination of public opinion, South African teachers are dedicated and work hard to educate children under difficult circumstances. However, multigrade teachers, who need to plan and prepare for more than one grade per lesson, face special challenges. Beukes (2006) notes the absence of clear guidance for the combination of grades; inconsistent learner attendance; a lack of classroom management skills; mother tongue influences; grouping; and time management as some of the difficulties faced by rural multigrade teachers in Namibia. In Sri Lanka, according to Vithanapathirana (2010), there are many challenges to multigrade teaching, including high teacher absenteeism; the number of teachers deployed being less than the number of teachers teaching; low learner enrolment; and parents choosing to send their children to accessible, more popular schools, which leads to a decline in learners attending rural multigrade schools.

Tsoloakidis (2010) states that socio-economic development can be defined as economic development followed by specific social improvements, such as a reduction in poverty, unemployment and inequality; better education and health care; and an improvement in moral values. In South Africa, despite government efforts to relieve adversity, poverty is still rife and poor education still fails to lift people out of it (Joubert 2010). Equality is essential in ensuring that all South African children have access to quality education where they can learn in an environment free from bias and discrimination (Asmal 2001). Most rural children adopt the disposition of their families and communities, who in most cases are unschooled and have very poor literacy skills. Downey, Von Hippel and Hughes (2008) note that students at rural schools are more likely to be poor and to rank in the bottom quintile for learning.

According to Joubert and Jordaan (2010), the Department of Education (DoE) has yet to recognise the pedagogy of multigrade teaching. Teacher training programmes and curriculum support programmes have not been developed to support multigrade teachers. Similarly, in Iran, the curriculum used in rural multigrade classrooms is the same as for urban monograde classrooms (Aghazadeh 2010). This implies that multigrade teachers in Iran comply with the curriculum as set out by their government. The Iranian education authorities have been developing structural, planning, training and development solutions in order to address the problems in their curriculum development.

Writing is a skill that can easily be taken for granted. For most rural multigrade teachers and learners, it is a process and an opportunity to learn to become independent writers. Learners need to acquire this skill in order to break free from the stigma and stranglehold of poverty and illiteracy. UNESCO defines writing and literacy as

[T]he ability to identify, understand, interpret, create, communicate and compute, using printed and written materials associated with varying contexts. Literacy involves a continuum of learning in enabling individuals to achieve their goals, to develop their knowledge and potential, and to participate fully in their community and wider society.

(UNESCO 2004:13)

Writing remains the most common form of communication. However, it is a complex skill and children need knowledgeable others to help them develop it. According to Potgieter (2010), multigrade schools account for 30% of all primary schools in South Africa; however, in most cases, the teachers at these schools are neither qualified nor able to provide quality education to their learners, including teaching them to write adequately and independently.

The National Education Evaluation & Development Unit (NEEDU) National Report 2012 (NEEDU 2013) states that learners in the foundation phase should be writing four times a week, including one extended piece of writing. The grade requirements for writing are as follows: Grade 1 - writing sentences; Grade 2 - writing paragraphs; and Grade 3 - extended passages. In order for teachers to teach writing effectively, they need to have teacher knowledge. The report highlights three aspects of teacher knowledge, namely subject knowledge, knowledge of the official curriculum, and knowledge of how to teach the subject. A joint Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) and Education Policy Consortium (EPC) study commissioned by the Nelson Mandela Foundation found that inadequate training affects teachers' ability to meet the high expectations of the writing curriculum. In addition, teachers are further hampered in their work and ability to teach by inadequate resources and support. Learners cannot learn to write without being taught the necessary skills or having pencils, books or paper (HRSC/EPC 2005).

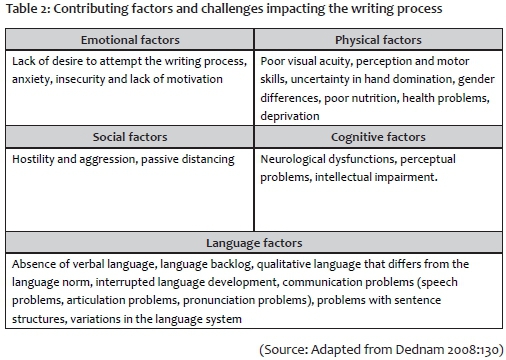

There are many obstacles to writing clearly and logically. Dednam (2008) states that children make spelling errors due to difficulties with letter-sound relations; they ignore spelling rules and write phonetically. Incorrect letter formation and the addition of unnecessary lines and curls exacerbate writing problems. Poor word and letter spacing, uneven slanting of letters, poor line quality, uneven letter size and incorrect placement of letters make it hard for readers to understand what the writer is trying to communicate. The NCS (DoE 2001b) and Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) (RSA DoE 2011) make provision for spending time on the correct formation of letters during handwriting lessons. Table 2 highlights the contributing factors and challenges presented by children which negatively impact the writing process.

Theoretical framework

The present research was conducted in a rural area where poverty and illiteracy prevail, therefore social and cultural constructs had to be carefully considered. The study was underpinned by Bronfenbrenner's social ecological systems theory with regard to addressing social and cultural issues and barriers to writing. Miller (2011) refers to the four systems in Bronfenbrenner's bio-ecological model of child development and how these complex interacting environmental contexts affect learning:

- The microsystem: The level closest to the learner, where there are immediate face-to-face interactions with another person. This system is concerned with the immediate environment and affects the physical, social and psychological wellness of learners.

- The mesosystem: The relationship between the learner, parents and teachers. This system influences how the child functions in the school environment while learning to write (Swart & Pettipher 2005).

- The exosystem: A level further away from the learner, which may influence the learner indirectly, such as the parents' place of work or the health services available to the community. In this study, the fact that their parents were farm workers directly influenced the learners work.

- The macrosystem: The level furthest from the learner that impacts on general cultural belief systems which include democracy, social justice, equity, equality and freedom from discrimination. Social factors such as poverty and discrimination, evident in this study, are important factors when considering the challenges teachers experience when attempting to teach writing (Swart & Phasha 2005).

Methodology

The methodology used was a qualitative study embedded in an interpretive case study. An interpretive case study takes a phenomenon, or our perception of a phenomenon, as starting point (Coe 2012). It aims to represent, describe and understand particular views of the educational world. In this case, the aim was to understand the challenges that rural multigrade foundation phase teachers face in the teaching of writing skills.

Sample

The sample consisted of two rural multigrade foundation phase teachers from two schools in the Western Cape (Teacher A - School A; Teacher B - School B). Based on a situational and contextual analysis (Henning, Van Rensburg & Smit 2007), purposive sampling was done in a non-random manner, based on member characteristics and specific criteria relevant to the research problem (Wiersma & Jurs 2005).

Teacher A was Afrikaans-speaking and taught an Afrikaans Grade 2/3 multigrade class. This class was visited once and observed four times over a period of four weeks from mid-July to the end of August 2010. The visits were made on alternate Mondays from 08.30 to 10.00, which was when writing was taught.

Teacher B, at School B, became part of this research project in 2011. She also taught Afrikaans to a Grade 2/3 multigrade class, and was Afrikaans-speaking herself. One visit and four observations were made at this school every Tuesday from 08.30 to 10.00 over a four-week period.

School and classroom contexts

School A is located at the edge of a rural community and is surrounded by sand and some tar. There was no grass was growing in the playground area, but the grounds were neatly kept and the exterior of the school building had recently been painted. The principal had an assistant to help with his teaching duties, which freed him up for administrative duties. There was also a receptionist and a bursar. There were thirty-nine learners in Teacher A's class, comprising of twenty-three boys and sixteen girls; of this group, twenty learners were in Grade 2 and nineteen in Grade 3. Three boys and two girls had already repeated the phase, making them older than their peers. Although the classroom was spacious, the teacher did not utilise the space adequately. The walls could have done with a coat of paint and there was a lack of storage space as well as books and general resources.

School B is surrounded by farmlands and has spectacular views of the nearby farms. The buildings were in good condition. There were some trees, grass and play equipment, but most of the playground and the surrounding grounds were covered in bare sand. Teacher B had forty-five learners in her class - twenty-five learners in Grade 2 and twenty learners in Grade 3. Fifteen learners were reported to have repeated a grade before and were older than their peers. Although there were learning aids on the walls, the classroom space was small, with little room for the desks, carpet or shelves, and could barely accommodate all the learners comfortably.

Site

The Northern District Education Office was approached to help identify schools that met the study requirements, that is, rural schools that were close to the researcher's home and place of work and which had multigrade classes in the foundation phase. Two schools located within 30 km from the researcher's home were identified. School A was situated on the outskirts of a quaint rural town and School B was located about 10 km from the nearest town.

Data collection techniques

In order to gain a deeper insight into, and a broader perspective of, the challenges faced by the two foundation phase teachers in teaching writing skills in the context of rural multigrade classes, the data capturing methods included one personal interview with each teacher and four video-recorded classroom observations at each school.

An observation schedule (Henning et al 2007; McMillan & Schumacher 2006) was designed to look for and note specific behaviours and focus on the teacher's methodology. The observation schedule guided the classroom observations, enabling the researcher to record video and hence document authentic data of the teachers' writing skills lessons (Fraenkel, Wallen & Hyun 2012; Walsh 2001).

The in-depth personal interviews with each teacher were conducted after school hours in their respective classrooms. The researcher found the interviews insightful, as they made it possible to discover and record the lived experience of the teachers and what and how they thought and felt (Mears 2012) about teaching writing.

Data analysis

The Afrikaans video recordings and interview data were transcribed and English translations were made. Both the Afrikaans transcripts and English translations were then returned to the teachers to check the accuracy of the translations to ensure that they were reliable and that there was a correlation between the data collection methods (Creswell 2012).

The transcripts were read and examined repeatedly in order to obtain an overall impression of the challenges experienced by the two teachers (Creswell 2012). The challenges were coded according to discreet units of meaning deemed relevant to the research question. Redundant data was eliminated. The units of meaning were grouped in a meaningful way based on the literature review and theory. Finally, superordinate themes were developed by identifying the relationship among the codes in a cluster (Cohen, Manion & Morrison 2008; Henning et al 2007; Rapley 2011).

Trustworthiness

Although reliability and validity are debated from a quantitative standpoint, authors such as Cohen et al (2008); Dane (2011); and Creswell (2012) argue that qualitative research can be reliable and validated. Three essential goals had to be achieved throughout the research process, namely reliability, validity and triangulation.

Although the sample consisted of only two participants, the data collected provided noteworthy and reliable information about how these two rural teachers taught writing to their learners in a multigrade setting.

Validity was achieved by meticulously recording and continuously checking, comparing and interpreting all the results and findings. The transcribed interviews were sent to both teachers to be checked and clarified. Henning et al (2007) argue that in order to ensure validity, the researcher needs to check, question, theorise, discuss and share what has been researched.

A combination of data and theory triangulation was attained. Data triangulation was achieved by using four video observations per class, a scheduled observation checklist, two in-depth interviews, and policy documents.

Ethical clearance

In response to written requests, consent was obtained in writing from the WCED, as well as from the principals and the participating teachers of the two schools to conduct the study there. In addition, the university where the researcher was conducting her research granted ethical clearance for the study.

Data collection occurred in a stress-free environment, where the self-esteem of the teachers and learners were nurtured. In order for the teachers to be more comfortable, all communication and correspondence was conducted in Afrikaans.

It was stressed that all participants would remain anonymous and that the information gathered would remain confidential and would only be used for research purposes (Creswell 2009; Henning et al 2007).

Findings

Four main themes became evident in answer to the research question, 'What challenges do foundation phase teachers experience when teaching writing in rural multigrade classes?': poor socio-economic background, transport, parental illiteracy, and teacher challenges. The latter comprised the following five subthemes: reading problems; differentiated teaching; lack of resources; the language of learning and teaching (LoLT); and finally, the lack of writing support from the WCED.

Poor socio-economic background

Schools are arranged in terms of 'quintiles', with the poorest 20% of schools in Quintile 1, 2 and 3, and located in rural areas and townships. As these schools are under-resourced, they consistently underperform in comparison to the wealthier schools in Quintiles 4 and 5 (Gower 2008). Teacher A stated that even though they were poor and from different cultural backgrounds, the learners got on well with one another; however, it was evident from the interviews with the teachers that their learners' poor socio-economic background posed specific challenges to their teaching.

Both schools in the study are recognised as Quintile 1 schools, and as such, they provide learners one meal a day by means of government-subsidised feeding programmes. These meals are often the only daily meal that the children have and it is often this, rather than the desire to learn, which serves as an incentive for their attending school:

"Most of the learners probably only come to school because of the food, but there's no progress in their schoolwork. They cannot progress if they are hungry."

Teacher A

"This is probably the only meal most of them get."

Teacher B

Teacher B also expressed doubts about whether this meal was sufficient to sustain the learners. School B tried to supply each learner with a cooked meal at break time, but had recognised the necessity of providing extra nutrition and therefore supplemented it by giving learners a fruit or a sandwich at the other break.

The teachers expressed concern about their learners' poor nutritional status:

"I cannot go on holiday with peace of mind knowing that these learners may not get food while they are at home. It nearly broke my heart when we came back to school at the beginning of the term and I overheard one of the boys saying, 'I'm so glad to be back at school, I can't remember when I ate last!'"

This lack of nutrition was also evident during the classroom observations. The video recordings of these classes revealed that learners in both classes appeared unable to concentrate early in the morning when asked by the teachers to focus on a writing task and that they were preoccupied with the food that they would get at break time:

"When is it going to be break? I'm hungry."

Learner at School A

Besides lingering hunger, cold weather presented another physical challenge to both learners and teachers. The classroom observations were conducted during winter, and the learners could be observed coming to school without warm clothing. Both teachers commented about their learners' lack of warm clothing. Teacher A said that she would keep learners inside on cold days, rather than let them go out in the cold without suitable warm clothing, while Teacher B said that she had actually brought clothes to school for them:

"I bring warm clothes from home so that I can give these children who are cold something warm to wear. It's one thing to be hungry, but it's another ball game being hungry and cold at the same time."

The learners' poor socio-economic background challenged the teachers in another sense as well. Both teachers were constrained in terms of the authentic content that they could use in reading and writing texts, due their learners' limited knowledge of the world. For example, one teacher gave her learners a text about washing machines. Not having experienced washing machines, the learners could not engage with this text. It was however interesting to observe that some of the learners were rather street-smart, as suggested by conversations about cigarettes or hairstyles such as Mohawks and shaved heads.

The disadvantaged background of the learners in these two rural classrooms impacted on two of the systems in Bronfenbrenner's (2005, in Prinsloo 2005) complex bio-ecological model, namely the microsystem (the learners came to school too cold and hungry to learn) and the mesosystem (their impoverished home environments did not support learning), and presented significant challenges for both teachers in their attempts to teach writing skills to these learners, as it directly and indirectly influenced the learners and negatively impacted on their ability to acquire writing skills.

Transport

Both teachers reported transport-related challenges. According to them, only a handful of learners were from the local community and most of the learners relied on some form of transport to bring them to school from neighbouring farms and communities.

However, transport is often problematic for rural learners (Prinsloo 2005). Buses and taxi services need to be paid for. School A had a bus service, with at least four buses transporting the learners to and from their homes, but School B did not have this option available and relied on the voluntary service of two farmers who transported the children in a minibus and a canopied van, respectively. Both transporters had to make at least six trips to ensure that everyone arrived at school and returned home safely. This not only resulted in absenteeism and learners often arriving late, but also removed any chance for extra lessons to remediate writing challenges.

The evidence showed that three learners from School A frequently arrived late, thereby missing important input and writing demonstrations, which hampered their writing development. Their work was never complete and had many punctuation, grammar, spelling and spatial errors, which needed to be corrected. Again, this was problematic, as the teacher did not have the time from remediation during class time and the learners could not stay after school for extra lessons. This is another manifestation of the impact of exosystem factors (Bronfenbrenner 2005, in Prinsloo 2005), because the parents' place of work (the surrounding farms) and the fact that they did not reside in the immediate school vicinity caused learners to miss class, or important parts of it, and made it difficult for the teachers to offer further writing support to their learners.

Parentalilliteracy

Illiteracy was prevalent among the mostly farm-working parent bodies of both schools and there was no local support offered to assist the parents in developing their literacy level. Teacher A reported that, as a result, they were incapable of assisting their children with reading and writing tasks or of helping them to develop their literacy skills to a higher competency level, and expressed the hope that this situation would be remedied at some stage:

"I am not giving up hope that one day somebody will come and help these parents and things will change [...] At the moment I cannot send any writing tasks home because they will disappear or get too dirty and nobody will help the learners with their tasks."

Teacher A

Moreover, the parents had difficulty communicating with the teachers about their children's education:

"Most of the time, older siblings have to accompany parents to parent meetings to help them understand what the teacher is explaining. It is not always possible for the siblings to assist, so the parents don't come to school."

Teacher A

Parental illiteracy has a deleterious effect on how learners learn to write (Woolfolk, Hughes & Walkup 2008). Despite the teachers' efforts, the learners in the study showed very little interest in writing and appeared to be disengaged. Their lack of interest in reading and writing could stem from a lack of familiarity with the issues of written language and an inability to understand how writing works, since they were not encouraged to write at home (ibid).Their parents' illiteracy impacted on the children's bio-ecological mesosystem (Bronfenbrenner 2005, in Swart & Pettipher 2005) by hampering their language and writing development.

Teacher challenges

Five subthemes were identified within this main theme, namely reading problems; differentiated teaching and learning; lack of resources; the language of learning and teaching (LoLT); and the lack of writing support from the WCED.

Reading problems

Hamston & Resnick (2009) stress the reciprocal relation between reading and writing. This was also echoed by the teachers in the study, both of whom highlighted their learners' lack of reading skills as a reason for their poor writing skills. Although the focus of this research was on the writing practices of the two teachers, it was interesting to note that the most significant obstacle mentioned by both teachers in teaching the learners writing skills was the fact that the learners lacked basic reading skills.

Researcher: "What do you think, besides the parental illiteracy rate, is one of the factors for your learners not progressing in their writing skills as you would have hoped for?"

Teacher A: "They can't read."

Teacher B: "I can see it in their reading. They struggle to read simple stories. They don't understand what they read."

Differentiated teaching

Tomlinson (2005) enumerates the difficulties associated with differentiated instruction in multigrade classes. Both teachers in the study experienced difficulties in finding the appropriate level of teaching to match the policies of the WCED with regard to the different foundation phase grades each had their classes. In order to meet the different requirements of the curriculum for each grade, they should have used differentiated teaching strategies to teach writing skills to the Grade 2 and Grade 3 learners and also teach them separately. However, the data showed that both teachers struggled to this.

Although Teacher A had a spacious classroom, the video-recorded observations of her lessons always showed her teaching the Grade 2 and Grade learners at the same time and using the same pedagogical and methodological strategies for both groups. During the interview, she commented on her need to know more about how to teach writing in mixed ability groups:

Teacher A: "It would be nice if someone could come and demonstrate how to teach our children to write. I want to know different ways of teaching my children to write."

Researcher: "Do you mean something other than the curriculum?"

Teacher A: "They can come and demonstrate the curriculum as well."

Her comments were of interest, as she acknowledged that she lacked differentiated teaching strategies to teach writing skills, but could not identify exactly what it was that she wanted the WCED officials to demonstrate.

In contrast, Teacher B demonstrated a wealth of knowledge of how to teach writing and employed a variety of pedagogical and methodological strategies to teach her learners different writing skills. However, she did not always introduce differentiated teaching activities, perhaps as a result of the limited classroom space. This meant that addressing writing issues were approached as a whole class activity rather than an individual or grade group one.

Having the Grade 3 learners sit through lessons and material that they had already covered in Grade 2 might be viewed as time wasting, but it appeared that the repetition of information did benefit at least some of them. For example, some of the Grade 3 girls showed a marked interest while Teacher B was presenting a lesson on tenses to the Grade 2 group. The researcher noticed one particular Grade 3 girl who seemed to benefit from the exercise. She nodded her head and silently repeated what the teacher was saying to herself, indicating that this was a learning experience for her. Another girl removed a scrunched-up piece of paper from her chair bag and started writing. When the researcher approached to take a closer look, it was discovered that the girl was writing down the tenses from the board. When the teacher walked around the classroom to check the Grade 3's work, the learner scrunched the piece of paper into her pocket and pretended to focus on her work.

The video recordings show two instances of Teacher B having different expectations of the Grade 2 and Grade 3 learners. In the first example, during news writing, Teacher B reminded the Grade 2 learners that she wanted them to write five sentences, while Grade 3 learners had to write a short paragraph. The second instance occurred during a creative writing class. The Grade 2 learners were required to write ten sentences, while the Grade 3 learners had to write three paragraphs (beginning, middle and end). Teacher B understood that the outcomes for Grade 2 and 3 had to be different, in accordance with the curriculum requirements with regard to writing development in Grade 2 and Grade 3 (RSA DoE 2002).

Time constraints also hampered differentiated teaching, as both teachers had to teach two curricula in the time that, in a monograde class, is allocated for teaching a single curriculum. During the interview, Teacher B explained that her learners were not on the same level as average Grade 2 and 3 learners ("they lag behind in important skills development)", which is why she purposefully designed tasks and assessment to suit their specific needs:

"I do it so that these learners can also accomplish a sense of achievement and develop a more positive self-esteem."

Lack of resources

A lack of basic resources such as stationery, work cards and games posed a further challenge to the teachers at both schools and impacted negatively on the learners. For example, there were no games available in Teacher A's classroom, which meant that the learners were denied the valuable learning opportunity of playing educational games. In another example, during the interview, Teacher A expressed the desire to have someone demonstrate to her how to make work cards, but at the same time bemoaned the lack of time to make such resources:

Researcher: "Do you make use of work cards when you teach?"

Teacher A: "No, because I don't have any. I want to make some, but I want to see some examples. But then I must get someone to make them for me, because I don't get time to make any extra resources."

The evidence also showed that learners had poor organisational skills and failed to properly look after what little resources they had. Stationery (pencils, colouring pencils, crayons, erasers and sharpeners) was in short supply and was constantly getting lost. Because there were no sharpeners, both teachers used their own sharpeners to sharpen the learners' pencils. This meant that learners could not sit down and begin their writing tasks, which confirms Woolfolk et al's (2008) observation that very little teaching can occur when so many other activities are taking place. A video recording of Teacher B shows her expressing frustration about the constant search for lost stationery:

"Every day is a battle; you have to spend the first half an hour of your morning arranging stationery, because the children lose it. Yesterday they had a pencil but today they can't find it."

In addition to hampering the teachers' efforts at teaching, this situation also appeared to upset those learners who really looked after their stationery. They would put their things in their chair bag at the end of the school day only to come to school the next day and find that someone else had removed them. This was confirmed by the video recorded observations, which showed learners displaying a lack of respect for their own belongings and those of their peers, taking things without asking and leaving a variety of stationery lying about on the floor or carelessly tossing it into their chair bags. This behaviour echoes Teacher B's earlier comment of every day being a "battle", suggesting that these learners have to contend with a daily fight for survival and to find a voice.

From the perspective of Bronfenbrenner's bio-ecological model, the lack of resources impacts on the learners' mesosytem and negatively affects their experience of learning how to write (Swart & Pettipher 2005). It also places an added imperative on the schools and teachers, because, as Woolfolk et al (2008) explain, when the home lives of children are chaotic and unpredictable, the school must provide a firm but caring structure.

The language of learning and teaching (LoLT)

The language of learning and teaching (LoLT) poses a significant challenge to the teachers across South Africa (see NEEDU 2013). This was also true for the two teachers in this study. In both cases, the teachers were Afrikaans-speaking and taught their classes in this language. However, not all their learners had Afrikaans as home language. Teacher A's class of thirty-nine learners included three isiXhosa-speaking learners, who she said were struggling to cope because they did not speak Afrikaans.

She tried to overcome this difficulty with the help of a Grade 1 teacher who was isiXhosa-speaking, asking her to translate instructions, which affected the teaching and learning time of both classes. On one occasion during the class observations, the isiXhosa-speaking teacher came into the classroom and gave the isiXhosa learners an instruction, then pointed to the teacher and the books, and left. Although brief, this interlude negatively impacted on the learners' impetus to learn to write with meaning and understanding within the correct context.

Teacher B had two isiXhosa-speaking learners in her class of forty-five. Since she did not have recourse to a translator, she resorted to hand and facial gestures to explain instructions. The WCED LITNUM Strategy (WCED 2006) states that, where possible, a learner's mother tongue should be actively supported in the classroom. Evidence from the video recordings showed that, in the case of the isiXhosa-speaking learners, the teachers did not have the requisite language skills to do so.

Writing support from the WCED

The LITNUM Strategy (WCED 2006) focuses on the way that teaching and learning occurs in the classroom. The strategy aims to improve the proficiency of teachers by providing the necessary support to deal with critical aspects of classroom teaching, in order to guarantee effective teaching and learning of subjects and develop a high level of literacy and numeracy skills. When reflecting on the interviews with the teachers in the study and the video-recorded observations of their classes, it was significant to find that the following stipulations/requirements contained in the LITNUM Strategy were experienced as challenges by both teachers (Table 3).

In spite of LITNUM Strategy purporting to offer teachers the necessary support, it appears that the WCED is not explaining to teachers how to manage the planning and teaching of multigrade classes. As indicated above, Teacher A found it challenging to teach writing skills to a rural, multigrade class. She wanted more assistance from the WCED and clearly expressed her frustration during the interview:

"They must come and show us, but that has not happened. The year is over, how do you begin next year? Are we going to have to teach multigrade again? Nobody has ever shown me how. I just carry on with what people say, so when they leave, they take the results and that's it [...] 'Yes,' they say, 'it is easy.' They come in here and tell you to do this and this. They tell you to give the learner who is restless a book. But how can you only give one learner a book? The others are also going to say, 'But I also want to read a book, because that one is drawing.' The WCED makes demands, but offers very little support in order to meet these requirements."

Teacher B was less concerned about WCED support and expressed more concern about her own teaching methodologies and how she could improve her learners' writing processes and strategies:

I am constantly looking for ways to assist these learners to understand and remember what I have taught them. They are capable of so much more and I will continue to try every method I know to help them.

It is clear from Table 3 that very little of the LITNUM Strategy had been implemented by the teachers in the study. From Teacher A's remarks, it appears that demands are constantly made on teachers, but much needed support in rural multigrade education is lacking, with virtually no explicit support and assistance from WCED officials. Moreover, as is evident from the NEEDU report (NEEDU 2013), this situation is not confined to the Western Cape, but applies on a national level. This unsupported educational environment, where there is little practical or tangible assistance for teachers on the part of the authorities, is linked to Bronfenbrenner's exosystem model (Prinsloo 2005).

Conclusion

The emphasis of this study was on the challenges experienced by two foundation phase teachers in teaching writing to their multigrade, rural classes. The study was underpinned by Bronfenbrenner's bio-ecological model (2005, in Prinsloo 2005), which is oriented toward a social realist position. The study therefore viewed writing as a social activity, where the environment in which children develop has a direct impact on their learning, including the acquisition of writing skills. This environment is in turn affected by many factors, such as poverty, illiteracy, illness, and the occupations of family members. The study drew three main conclusions with regard to Bronfenbrenner's interacting bio-ecological systems, that is, the microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem and macrosystem, and how these aspects impact on the teaching of writing skills.

First, the impact of poverty and illiteracy on the development of rural children must be acknowledged and addressed. The theme of poverty forms a thread running through all four of Bronfenbrenner's systems. It is easy to take basic necessities such as water, nutrition, a supportive family and warm clothes for granted. But many rural children lack these basic resources, and without them, effective learning and the development of effective writing skills will continue to be hampered. The national Department of Education should therefore prioritise this problem.

Second, there is an urgent need for curriculum and resource development for rural multigrade teachers, particularly with regard to the teaching of writing skills. This study shows that the change of curriculum has not solved the unique problems of multigrade education. Teachers need stability, but also ongoing training to enable them to effectively teach (writing) in a multigrade environment and remain up to date with curriculum changes. Interactions between teachers and learners are located within Bronfenbrenner's mesosystem, and directly influence learners' academic skills. All pre-service teacher training institutions should therefore include a module in their training that exposes students to the complexity of teaching in (rural or urban) multigrade environments.

Finally, the teaching of writing should be prioritised in teacher training institutions and should also be offered, on an ongoing, part-time basis, by knowledgeable others such as NGOs, the provincial educational departments, or the national Department of Education, for example in the form of in-service workshop. In addition, such training should be easily accessible and affordable to all teachers.

References

Aghazadeh MA. 2010. Multigrade education in Iran. Unpublished paper presented at the Southern African Conference for Multigrade Education, 22 - 24 March 2010, Paarl, South Africa.

Asmal K. 2001. The Manifesto on Values, Education and Democracy. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Berry C & Little A. 2007. Multigrade teaching in London, England. In: A Little (ed). Education for all and multigrade teaching: challenges and opportunities. Amsterdam: Springer. 67-86. [ Links ]

Beukes FCG. 2006. Managing the effects of multigrade teaching on learner performance in Namibia. Unpublished MA thesis. Johannesburg: University of Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Bloch G. 2009. The toxic mix: what is wrong with South Africa's schools and how to fix it? Cape Town: Tafelberg. [ Links ]

Coe R. 2012. The nature of educational research - exploring the different understandings of educational research. In: J Arthur, M Waring, R Coe & LV Hedges (eds). Research methods & methodologies in education. London: Sage. 5-13. [ Links ]

Cohen L, Manion L & Morrison K. 2008. Research methods in education. 6th Edition. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Cornelissen R. 2011. WCED systemic results. PowerPoint presentation. CPUT Staff Room, Mowbray, Cape Town, 25 February.

Cornish L. 2010. Multigrade teaching in Australia. Unpublished paper presented at the Southern African Conference for Multigrade Education, Paarl, South Africa, 22 to 24 March.

Creswell JW. 2012. Educational research: planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. 4th Edition. Boston, MA: Pearson. [ Links ]

Dane FC. 2011. Evaluating research: methodology for people who need to read research. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Dednam A. 2008. First language problems. In: E Landsberg, D Kruger & N Nel (eds). Addressing barriers to learning: a South African perspective. Pretoria: Van Schaik. 119-144. [ Links ]

Downey DB, Von Hippel PT & Hughes M. 2008. Are "failing" schools really failing? Using seasonal comparison to evaluate school effectiveness. Sociology of Education, 81(3):242-270. [ Links ]

Fraenkel JR, Wallen NE & Hyun HH. 2012. How to design and evaluate research in education. 8th Edition. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Gower P. 2008. All schools need decent funding. Mail & Guardian, 8 May 2008.

Hamston S & Resnick LB. 2009. Reading and writing with understanding. Washington, DC: The New Standards. [ Links ]

Henning E, Van Rensburg W & Smit B. 2007. Finding your way in qualitative research. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Hoadley U & Jansen J. 2010. In: U Hoadley & J Jansen (eds). Curriculum: organizing knowledge for the classroom. 2nd Edition. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. 93-168.

HSRC/EPC. 2005. Emerging voices: A Report on Education in South African Rural Communities. Research study commissioned by the Nelson Mandela Foundation. Cape Town: HSRC Press. [ Links ]

Joubert J & Jordaan VA. 2010. Pedagogy of multigrade. Unpublished paper presented at the Southern African Conference for Multigrade Education, Paarl, South Africa, 22 to 24 March.

Joubert J. 2010. Multigrade schools in South Africa: Overview of a baseline study conducted in 2009 by the Centre for Multigrade Education, Cape Peninsula University of Technology. Unpublished paper presented at the Southern African Conference for Multigrade Education, Paarl, South Africa, 22 to 24 March.

Little WA. 2005. Learning and teaching in multigrade settings. Unpublished paper prepared for the UNESCO 2005 EFA Monitoring Report. [Retrieved 12 February 2014] http://portal.unesco.org/education/en/file_download.php/548cfe4ac0864fcea666900c2144e4d1Little.doc.

Macintosh H. 2003. Managing Outcomes-Based Education (OBE). In: M Coleman, M Graham-Jolly & D Middlewood (eds). Managing schools in South Africa: managing the curriculum in South African schools. London: The Commonwealth Secretariat. 195-207. [ Links ]

McMillan JH & Schumacher S. 2006. Research in education: evidence-based inquiry. 6th Edition. New York, NY: Pearson. [ Links ]

Mears CL. 2012. In-depth interviewing. In: J Arthur, M Waring, R Coe & LV Hedges (eds). Research methods & methodologies in education. London: Sage. 170-175. [ Links ]

Miller PH. 2011. Theories of developmental psychology. 5th Edition. San Francisco, CA: Worth. [ Links ]

Mulryan-Kyne C. 2007. The preparation of teachers for multigrade teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23:501-514. [ Links ]

NEEDU (National Education Evaluation & Development Unit). 2013. National Report 2012: The State of Literacy Teaching and Learning in the Foundation Phase. Pretoria: NEEDU. [ Links ]

Padmanabha Rao YA & Rama A. 2010. Redesigning the elementary school - multilevel perspectives from River Rishi Valley Institute for Educational Resources. Unpublished paper presented at the Southern African Conference for Multigrade Education, Paarl, South Africa, 22 to 24 March.

Potgieter M. 2010. Ons vergete skole. Die Burger, 4 February.

Prinsloo E. 2005. Socio-economic barriers to learning in contempory society. In: E Landsberg (ed). Addressing barriers to learning: a South African perspective. Pretoria: Van Schaik. 27-41. [ Links ]

Rapley T. 2011. Some pragmatics of data analysis. In: D Silverman (ed). Qualitative research. 3rd Edition. London: Sage. 271-296. [ Links ]

RSA DoE (Republic of South Africa. Department of Education). 2001a. Manifesto on Values, Education and Democracy. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

RSA DoE (Republic of South Africa. Department of Education). 2001b. National Curriculum Statement. Grade R to 9 (Schools). Policy document. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

RSA DoE (Republic of South Africa. Department of Education). 2002. Revised National Curriculum Statement. Grade R to 9. Policy document. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

RSA DoE (Republic of South Africa. Department of Education). 2008. Foundations for Learning and Assessment Framework. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

RSA DoE (Republic of South Africa. Department of Education). 2011. Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Shor I. 1999. What is critical literacy? In: I Shor & C Pari (eds). Critical literacy in action: writing words, changing worlds. Portsmouth: Heinemann. 1-30. [ Links ]

Swart E & Pettipher R. 2005. A framework for understanding inclusion. In: E Landsberg (ed). Addressing barriers to learning: a South African perspective. Pretoria: Van Schaik. 3-23. [ Links ]

Swart E & Phasha T. 2005. Family and community partnerships. In: E Landsberg (ed). Addressing barriers to learning: a South African perspective. Pretoria: Van Schaik. 213-236. [ Links ]

Taylor N. 2008. What's wrong with our schools and how can we fix them? Unpublished paper presented at the CSR in Education Conference, Cape Town, 21 November.

Tomlinson CA. 2005. Grading and differentiation: paradox or good practice? Theory into Practice, 44(3):262-269. [ Links ]

Tsolakidis C. 2010. Multigrade issues: a policy required. Unpublished paper presented at the Southern African Conference for Multigrade Education, Paarl, South Africa, 22 to 24 March.

UNESCO. 2004. The plurality of literacy and its implications for policies and programs. UNESCO Education Sector Position Paper 13. Paris: UNESCO.

Vithanapathirana MV. 2010. Multigrade teaching innovations in Sri Lanka and challenges of scaling-up. Unpublished paper presented at the Southern African Conference for Multigrade Education, Paarl, South Africa, 22 to 24 March.

Walsh M. 2001. Research made real: a guide for students. Cheltenham: Nelson Thornes. [ Links ]

WCED (Western Cape Education Department). 2006. Literacy and Numeracy Strategy 2006-2016. Cape Town: Edumedia. [ Links ]

Wiersma W & Jurs SG. 2005. Research methods in education. 8th Edition. New York, NY: Pearson. [ Links ]

Woolfolk A, Hughes M & Walkup V. 2008. Psychology in education. London: Pearson. [ Links ]