Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Childhood Education

On-line version ISSN 2223-7682

Print version ISSN 2223-7674

SAJCE vol.4 n.1 Johannesburg 2014

"We are workshopped": Problematising foundation phase teachers' identity constructions

Kerryn Dixon; Lorayne Excell; Vivien Linington

University of the Witwatersrand. Email: kerryn.dixon@wits.ac.za; lorayne.excell@wits.ac.za; vivien.linington@wits.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The new Minimum Requirements for Teacher Education Qualifications (MRTEQ) document outlined by the Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) envisages a particular type of teacher. These teachers need to be, amongst other things, reflective, committed, critical practitioners with sound content knowledge (DHET 2011). It is with this in mind that a remark made by a foundation phase teacher in Limpopo raised several questions for the research team investigating communities of practice in the foundation phase. The fact that teachers considered themselves to be "workshopped", where something is done to them, is in opposition to the kind of teacher envisaged by government, which sees teachers as pivotal to educational transformation. This paper unpacks the implications of teachers constructing themselves as "workshopped" and its relation to workshops as vehicles through which knowledge is acquired. Using Halliday's (1994) systemic functional linguistics (SFL), two instances of this statement used by teachers are analysed. We consider how the mode of the workshop currently presented as a form of professional development is inimical to knowledge acquisition and how it may even negatively impact a teacher's ability to reflect on pedagogical gaps.

Keywords: Workshop, foundation phase teachers, identity construction, discourse analysis

Introduction

"We are workshopped" is a claim made by a foundation phase teacher during a recent interview in Limpopo province. Over a number of years, in a number of research contexts and across provinces each of the three authors has heard this statement in conversations with teachers. It seems to have entered into teacher discourse and become an accepted and naturalised way for teachers to express their experience of attending workshops in the context of ongoing teacher education. It is the nature of this statement that caused us to pause and reflect on its meaning and implications for practice.

This statement "we are workshopped" troubles us. Janks (2010:61) argues that people make:

Lexical, grammatical and sequencing choices in order to say what they want to say. All these selections are motivated: they are designed to convey particular meanings in particular ways to have particular effects. Moreover they are designed to be believed.

Janks's argument is the starting point for this article: To interrogate what has become a commonplace statement by considering the meaning conveyed in this phrase, what effects it has and the implications of believing this particular statement. We draw on data from foundation phase teachers who used this statement in conversation with us and read it against recent literature on teacher identity and policy documents such as Norms and Standards for Educators (DOE 2000) and the Minimum Requirements for Teacher Education Qualifications (MRTEQ) (DHET 2011) that present an idealised construction of the teacher. We argue that the representation of teachers in these documents is in contrast to the passive "we are workshopped" identity articulated by the teachers we interviewed. Furthermore, this aspect of their articulated identity is not concomitant with the kind of teacher this country requires for educational transformation and, in addition, raises questions about the efficacy of the workshop as a mode of delivery for in-service professional development.

We begin by discussing some of the literature on teacher identity and the ideal teacher as constructed in policy documents. We use Halliday's (1994) systemic functional linguistics (SFL) as a tool to analyse the statement "we are workshopped" and then examine two examples of the ways in which teachers, one from Limpopo and one from Gauteng, use this statement in ways we believe exemplify its common usage.

Teacher identity and agency

Poststructuralist literature contests the notion of a unified, fixed, essentialised identity. Rather, identity is foregrounded as dynamic, fluid and multifaceted (Blackledge & Pavlenko 2002). Identity is maintained by social and material conditions, but these conditions can lead to contradictions between the different identity positions that people take up (Woodward 1997). There may also be a mismatch between the collective and the individual (Welmond 2002). With regard to work on teacher identity in the South African context, Jansen (2001:242) cites the work of Drake, Spillane and Hufferd-Ackles who describe teachers' identities as "their sense of self as well as their knowledge and beliefs, dispositions, interests, and orientation towards work and change". Thus, the way teachers feel about themselves professionally, emotionally, and politically (Jansen 2001) may shift based on the social and cultural conditions under which they work, and other identity positions they take up in their lives. Their teacher identity may also be in tension with official representations in policy documents.

The statement "we are workshopped" flags identity issues which alert us to the importance of exploring teacher identity in the South African educational landscape. We read this statement as an expression of teachers' working conditions and its lexical and grammatical construction as evidence of how this affects them professionally, emotionally and politically. In fact, Sachs (2005:15) asserts:

Teacher professional identity ... stands at the core of the teaching profession. It provides a framework for teachers to construct their own ideas of "how to be", "how to act" and "how to understand" their work and their place in society. Importantly, teacher identity is not something that is fixed nor is it imposed; rather it is negotiated through experience and the sense that is made of that experience.

The sense teachers make of attending workshops has, we contend, played a mediating role in our participants' construction of their identities. This claim resonates with Welmond (2002:42) who argues that teacher identity refers to both the personal experience of teaching and role of teachers in a given society. It includes both the subjective sense of individuals who engage in the occupation of teaching and how others view teachers. A workshop potentially provides personal experiences for teachers, but the types of workshops presented also give clues about how teachers' roles are collectively envisaged in a society. The state's view of teaching and the role of the teacher are embedded in presented workshops.

There is little doubt that state apparatus, in this case its teacher development programmes, has played some part in the construction of identity held by the subjects of this paper. Welmond (2002:43) makes the case:

Because the development and maintenance of a mass education system are important functions of modern nation-states, the role that the state reserves for teachers is a critical factor shaping teacher identity. Of all the forces that influence teachers, the state's objectives for education are perhaps the most determining ones.

The state's objectives and expectations for teachers are set out in the Personnel Administrative Measures (PAM) document. It explicitly states that ongoing professional development is expected, and core professional duties include attending "meetings, workshops, seminars, conferences, etc" (DOE 2003:5). Other roles are outlined in a number of other policy documents and an examination of these documents lends credence to Jansen's (2001) claim that conflict can exist between the policy representations of teachers and their personal identities as practitioners. Furthermore, he suggests that this identity conflict might lie at the heart of the implementation dilemma in educational reform. The vision of this reform can be seen in the South African policy documents which contain idealised images of teachers. Gilmour and Soudien (2009) take this argument one step further in their consideration of the current state of education. They argue that the national curriculum, which began its roll out in 1998, envisioned a teacher that does not exist. The reality is in fact a "deprofessionalised corps operating in schools" (Gilmour & Soudien 2009:288). If this is the case, then it will take more than idealised policy constructions of teachers to counter this kind deprofessionalisation. We would argue that although this ideal teacher constructed in the policies may not fully exist in reality, many teachers embody aspects of a professional teacher identity.

Idealised constructions of the teacher in policy documents

Since 2000 all teachers, both newly qualified and experienced, are required by policy documents to meet a set of minimum requirements. Teachers are expected to take on seven roles of the teacher which were first articulated in the Norms and Standards for Educators (NSE) document (DOE 2000). Ongoing educational review has led to the NSE being replaced in its entirety by the National Qualifications Framework Act 67 of 2008: Policy on the Minimum Requirements for Teacher Education Qualifications (MRTEQ) (DHET 2011).

The MRTEQ (DHET 2011:7) acknowledges that "teaching is a complex activity that is premised upon the acquisition, integration and application of different types of knowledge practices or learning". It highlights the need for competent teachers who are able to adapt to changing contextual situations and disregards what it labels a technicist approach based purely on skills that rely on the evidence of demonstrable outcomes as measures of success. As such, the various types of knowledge that underpin teachers' practice are encapsulated in the notion of integrated and applied knowledge. By explicitly foregrounding knowledge, reflection, connection, synthesis and research, the document gives renewed emphasis to what is to be learned and how it is to be learnt (DHET 2011).

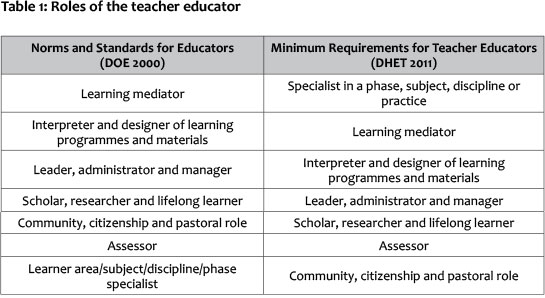

The seven roles of the teacher contained in the NSE have been retained in the MRTEQ. Their order has, however, been rearranged with the role of phase specialist being given priority (table 1). We argue that this reorganisation is significant in reshaping and reprioritising aspects of teacher identity.

The roles, the document argues, continue to be useful tools to assist in the design of learning programmes which, in turn, result in the development of teachers who are able to contribute to the collective work of educating children in a school at different stages of teachers' careers (DHET 2011). However, for the purposes of this paper, only four roles are described and interrogated in relation to the statement "we are workshopped".

Firstly, the teacher as the specialist in a phase, subject discipline or practice is someone who is:

Well-grounded in the knowledge, skills, values, principles, methods and procedures relevant to the phase, subject, discipline or practice. The educator will know about different approaches to teaching and learning (and where appropriate, research and management), and how these may be used in ways which are appropriate for the learners and the context. The educator will have a well developed understanding of the knowledge appropriate to the specialisation (DHET 2011:49).

This role is a demanding one for any teacher. It envisages a teacher who has indepth subject and phase knowledge and keen insight into planning, implementing and, in this case, managing the relevant learning programmes at the foundation phase level. This role suggests that the teacher has more than a superficial general knowledge of relevant subject matter. Teachers are also required to have deep insight into how children learn and be fully aware of contextual factors that might impact learning. In fact, this role requires the foundation phase teacher to be both a phase and subject expert. It alludes to a proactive teacher; one who can take initiative to ensure that learners are both stimulated and challenged in the classroom by employing a variety of suitable teaching strategies.

The second role we interrogate is that of learning mediator. This role is described as follows:

The educator will mediate learning in a manner which is sensitive to the diverse needs of learners, including those with barriers to learning; construct learning environments that are appropriately contextualised and inspirational; and communicate effectively, showing recognition of, and respect for the differences in others. In addition, an educator will demonstrate sound knowledge of subject content and various principles, strategies and resources appropriate to teaching in a South African context (DHET 2011:50).

This definition requires a complex set of skills and mastery. We note that learning mediation is framed in terms of difference and diversity before the final sentence, which explains the concept of learning mediation. Effective mediators promote learning through the use of a variety of strategies and teaching and learning resources (MacDonald 1991). This in itself is a complex act; mastering effective classroom talk that presents sound content in a meaningful way is a daily challenge. Placing diversity first in this explanation potentially backgrounds the importance of learning. We are not arguing that understanding diverse needs and being sensitive to cultural differences is not crucial, nor should they be separated from the daily teaching, but rather that mediation of learning, which is the name of this role, is a complex act that should be foregrounded. Sensitivity to culture and diversity are not unique to this role and should be reflected in all the roles.

Teachers' deep knowledge and ability to plan should manifest themselves in the third role, interpreter and designer of learning programmes and materials. This is outlined as such:

The educator will understand and interpret provided learning programmes, design original learning programmes; identify the requirements for a specific context of learning; and select and prepare suitable textual and visual resources for learning. The educator will also select sequence and pace the learning in a manner sensitive to the differing needs of both the subject and the learners (DHET 2011:50).

This too, is a demanding role for teachers. It also suggests a contradictory role which has to be delicately negotiated by teachers. On the one hand, they are required to be able to follow a predetermined learning programme. On the other hand, teachers are expected to be designers of original learning programmes. Deciding when to follow and when to design a programme requires, we suggest, a lot of initiative and fortitude. Teachers are also required to select and prepare appropriate learning and teaching support material, sequence and pace lessons in accordance with the subject requirements and the needs of the learners. We would argue that this role is a nuanced one that, in reality, demands that a teacher be a spirited, creative, flexible and independent thinker who can adjust to ever-changing classroom contexts.

Teachers also have to fulfil a community, citizenship and pastoral role. MRTEQ states:

The educator will practice and promote a critical, committed and ethical attitude towards developing a sense of respect and responsibility towards others. The educator will uphold the Constitution and promote democratic values and practices in schools and society. Within the school the educator will demonstrate the ability to develop a supportive and empowering environment for the learner, and respond to the educational and other needs of learners and fellow-educators. Furthermore, the educator will develop supportive relations with parents and other key persons and organisations, based on a critical understanding of community and environmental issues. One critical dimension of this role is HIV/AIDS education (DHET 2011:50).

This role could be seen to underpin the other roles. It envisages that teachers will behave in ways that are far removed and much more demanding than merely being the passionate and nurturing teacher who loves children (Day & Kington 2008). It requires the teacher to be both a role model and a teacher of democratic values and practices; a person who teaches for democracy, through democratic practices. In fact, this requires a teacher who is able to promote those identified dispositions in children such as responsibility, perseverance, curiosity and trust that support and enrich learning (Carr 2001). The success of this role requires cultural awareness and an understanding of diversity, although it is not explicitly stated. In short, this role creates the image of a proactive teacher who can take the initiative, negotiate difficult learning terrain, reflect critically and work collaboratively with all members of the school community.

In taking on these roles, we argue that teachers need to negotiate their individual identities in relation to the collective and social and material conditions under which they work.

Analysing the statement "we are workshopped"

In thinking about the statement "we are workshopped", we felt that it was important to define what the word workshop means. In its original usage, workshop was used as a noun. It is the room or place in which items are made (Corpus of Contemporary American English 2013). In its modern usage it also refers to a "usually brief, intensive educational program for a relatively small group of people that focuses especially on techniques and skills in a particular field" (Corpus of Contemporary American English 2013). Workshops are described as instances where a group of people usually work collaboratively in an interactive or hands-on way. In an educational setting a workshop's aim may be to improve an aspect of practice in an interactive way.

The term is ubiquitous in educational settings, but the meaning appears to have shifted. Informal conversations with teachers and presenters, in fact, reveal that such training/short courses are often not the interactive group collaborations that define a workshop, but more often a transmission model of training with large numbers of teachers attending. This was evidenced by the initial CAPS training in Gauteng. Thus, the way the word workshop is currently used colloquially, we would define as, some form of input for teachers to improve knowledge and skills that are not necessarily delivered in an interactive mode for a small group. And, we would argue, this mode of presentation is ironically at odds with the concept of leaner-centred education.

The construction of this statement was interesting. We used aspects of Halliday's SFL to analyse the statement and interrogate its meaning. Language, for Halliday (1994:xvii), is a "system for making meaning"; a social semiotic resource that people use. Rather than foregrounding an analysis of syntax and surface structures, SFL emphasises the choices made in producing linguistic structures during communicative acts. Halliday (1978) argues that language transmits, maintains and can change the social order.

Understanding that the "lexical, grammatical and sequencing choices" teachers make are motivated (Janks 2010:61) and that these particular choices then negate other choices, provides some insight into how teachers construct their professional identities.

Halliday (1994:101) posits that the framework he provides for analysing clause structure (in this case, "we are workshopped") is important because it provides the "frame of reference for interpreting our experiences of what goes on". This framework has three aspects: The process (what is going on), the participants (the who or what of the process) and the circumstances under which the process happens.

In terms of the participants in this clause, the participants are referenced by the pronoun "we", which implies that the speaker sees herself as part of a group. When these workshops comprise a group of teachers coming together for a particular purpose, it is unsurprising that the speaker identifies herself as belonging to this group. A second set of participants, those who run the workshop, are absent in this construction. But, in the second example from teacher interviews that we present later in this paper, this teacher made a different lexicogrammatical choice by saying, "they workshopped us", which introduces the missing nominal group. This group is also referred to using a pronoun. "They" refers to the DOE officials who run the workshops. Workshops are seldom run by groups. Workshops are usually run by an individual presenter/facilitator. It could be argued that the use of "they" and "we" constructs an us/them binary. In this construction the workshop presenters represent the education department which is set against teachers as another group rather than different stakeholders who all attended a workshop in different capacities.

The use of pronouns in the two constructions reveals the working of power relations where the "they", the education department, does things to the "we", the teachers. Fairclough (1989:33) notes that:

Institutional practices which people draw upon without thinking often embody assumptions which directly or indirectly legitimize existing power relations. Practices which appear to be universal and commonplace can often be shown to originate in the dominant class or the dominant bloc, and to have become naturalized (original emphasis).

Going to workshops organised and run by the department is what teachers are expected to do - the practice of attending these often compulsory events is a part of teachers' discourse. The fact that the presenter is not named, although workshops can be and are run by other organisations and experts apart from the education department, could imply a number of things. It might be that the audience who hears this statement knows that the absent participant/s (or the "they") is/are connected to the department because they are likely to form part of the group referenced by the pronoun "we". The lack of specific reference to who runs the workshops may indicate a lack of knowledge of workshop content and/or presenters' identities. This was the case with Miss G, the teacher we discuss later in the paper.

In analysing the processes involved (what is done), the use of the verb "are" indicates a relational process, a process of being. In the teachers' grammatical construction, the use of the verb "are" implies a relational process: x = y (Halliday 1994). This means that the x, "we", is in essence the outcome of the workshop rather than the people involved in a workshop who collaboratively or interactively make something or improve skills or practice. When "workshopped" is used as a verb it usually implies that something (like a play) is worked on to produce a particular outcome (e.g. an adapted play). What is implicit in this particular usage is that people interact together to create an outcome. ("We workshopped the play to perform for a school audience"). But, in the workshopped construction, the use of the present passive implies a lack of agency. Something is done to the group.

We would argue that there are possibly traces of the older meaning of workshop present here. In this usage of workshopped, what is made are the teachers. They are what emerge from the workshop, rather than skills or techniques or new practices they have learned. This is also evident in the construction: "They workshopped us". The image of teachers being constructed or reconstructed, worked on, rather than working together, works to position teachers as disempowered rather than empowered.

One concern that may be raised about our interpretation of this statement that constructs the teacher as passive and dependent rather than active and independent, relates to language usage. It could be argued that for second language speakers of English this statement may be a turn of phrase. But we have heard this statement across language and race groups. In discussions with African language speaking colleagues about how this sentence would be said in African languages, it appears this statement is not a direct translation into English. This sentence is not a grammatically incorrect translation from these African languages. Rather, it is a reflection of how teachers from different racial and linguistic backgrounds construct their experience of the workshop as disempowering, and thus it raises questions about the professional identity of many teachers in this country. It also raises questions about the type and quality of training that is made compulsory for them to attend.

In addition, neither of the statements ("we are workshopped" and "they workshopped us") contain any information about the circumstances (time, place, manner) in which these workshops take place. This information could easily be given by teachers. The fact that no reference is given to circumstances within these sentences, we argue, is important for teachers. The lack of specific circumstances could be seen to be indicative of a process that holds little value for teachers in increasing their own knowledge base and skills, and thereby contributing to a strong professional identity. Or, as reflected in the use of the simple present tense, the repeated action may in fact be a mundane and forgettable event that does not stand out as worthwhile. This point is strengthened when one considers pronoun choice and the absence of names of workshop presenters.

Data set and analysis

In January 2013, when reviewing data collected in an ongoing research project into foundation phase teacher development, the authors were struck by a remark made by one participant that she "had been workshopped". Further reflection by the authors revealed that over a period of at least five years they had all heard similar remarks being made by research participants in a number of different research projects located within the foundation phase (Excell, 2011; Dixon; 2011; Wits School of Education, 2009). In all these instances we had heard this statement in informal conversations with teachers and it re-emerged in semi-structured interviews.

The four research projects mentioned above were all investigating specific aspects of foundation phase pedagogy. All the projects were qualitative in nature and the number of participants varied from six in the smallest project to eighty three in the largest of these projects. In all projects data collection followed a similar pattern. After obtaining permission and ethical clearance for the research, we began with classroom observations. The observation periods varied in length. In all of the projects specific foundation phase lessons were observed. The researchers took detailed field notes during the observations. The observations were guided by the specific foci of the projects. In the two instances we present here the observation instrument was informed by the notion of productive pedagogies (Hayes, Mills, Christie & Lingaard 2006), which builds on the work of authentic pedagogies done by Newmann and Associates (1996). The observation schedule that provided the basis for the classroom observations was adapted from one used in an Australian study entitled, In Teachers' Hands (Commonwealth of Australia 2005). After each classroom observation, participants in all the research projects (n = 108) were invited to take part in an individual semi-structured interview. Common to all interviews were questions centring on teachers' perceptions of themselves and their views of curriculum development and implementation, as well as their own professional development. However, as already mentioned, it was only during our current research project that the remark "we are workshopped" struck a particular chord. We were then challenged to go back and retrospectively review previous data sets from the other three research projects to explore other instances of this usage when the participants had made reference to being "workshopped". This exploration, we thought, could provide insight into the effect and implications of the usage of this statement.

Twenty transcripts which contained references to workshops were identified. It is important to note that in none of the interviews was professional development through workshops a focus - rather this was unsolicited and raised by the teachers themselves. Had such a question been posed the incidence of this statement may have been higher across all the data sets. But what the data highlights is the usage of the statement in teacher discourse, particularly when teachers talk about professional development.

We present two examples of teachers' particular use of this statement: One experienced grade 2 teacher from Limpopo (Mrs L) and one relatively inexperienced grade R teacher from Gauteng (Miss G). The data selection was influenced by the fact that the teachers are located in different provinces, and that despite their different backgrounds, training and experience they both talked about being "workshopped". In addition, Miss G was interviewed in 2009, and Mrs L in 2012, which we contend depicts a particular state of being that appears to be consistent over a period of time.1 In the first example we consider the way in which Mrs L describes her experience of a workshop. In the second instance we examine the way in which content from a workshop was taken up by Miss G. In choosing only two examples we do not aim to make generalised claims about teachers' experiences of workshops. These examples illustrate the ways in which specific experiences of the workshop are represented and the implications of these experiences which, we argue, should be interrogated.

Mrs L's workshop experience

Mrs L has been teaching for 19 years. What was striking in her interview was her strong identification with her pastoral role. During the interview she stated she became a foundation phase teacher because she "likes working with small kids. I'm patient and small kids need a patient somebody." She further commented on the importance of laying a strong foundation to ensure children reach their academic potential. Like many foundation phase teachers, her professional identity is framed by a nurturing component (Anning, 1997, 2006; Day & Kington, 2008).

The pastoral role is not sufficient. Mrs L identified elements of other roles of the teacher when she said "it's important to know the curriculum, to know the kids and their background". She also discussed the importance of her own continuous learning:

You must keep on learning. Don't say that I'm teaching the small kids and then you relax and ... don't do anything ... You must keep on reading ... They keep on sending us the ... the different types of policies and if you don't read them [the policies], you won't be able to walk step by step with them [the children] in terms of the ever-changing education.

Despite her implicit acknowledgement of the roles of the teacher in terms of being a specialist in disciplinary and curricula knowledge, a learning mediator and lifelong learner, she admits to being overwhelmed by curricula changes and alternative pedagogies:

The education system is confusing us. Training ... OBE, [happened] out of the blue ... We start doing this and I'm not trained to do that thing. It becomes very difficult... We are trained for three days or for a week ... I think we have the knowledge; it's just the government is confusing us by ever changing the knowledge - we have got the knowledge - immediately when they introduced the new education system they must train us - train enough. The knowledge we have got, it's just that the government is confusing us... When we are still busy doing this they change ... adjust, and then they change to a new thing altogether ... They are confusing us ... Every five years ... [they the government] politicise education ... They keep on confusing us (our emphasis).

There is a tension in Mrs L's explanation. She states that she thinks she has the appropriate knowledge ("I think we have the knowledge"), but in the face of ongoing change they have confused her. Importantly, it is interesting that the passive construction re-emerges in the rest of her discourse. Mrs L makes five references to her confusion. Firstly Mrs L blames the system for her confusion - "the education system is confusing us". She then blames the government for the confusion ("the government is confusing us", "they must train us", "they keep on confusing us"), because they "change to a new thing altogether". Then she emphasises her discomfort with change by expressing it as a continuous state, "they keep on confusing us". The binary construction between us (the teachers) and them (the department) is apparent. Mrs L uses the first person pronoun to express what she understands about the group ("I think we have the knowledge"). Her use of the third person pronoun places her as a member of a group who has continuously been confused by them. Although she mentions it being necessary to read the policy documents, her insistence on training is seen as a panacea for confusion rather than an opportunity to draw on the knowledge and skills of a phase specialist.

Mrs L's remarks appear to indicate a loss of confidence and insecurity within her classroom. For example she references a normalised teacher-centred pedagogy that forms part of her teacher identity: "[We] are used to standing in front, most 'specially in foundation phase - and teaching them". This practice is challenged during workshop training:

We teach them and somebody comes and says you must not spoonfeed these kids, you must give them work to do. Just imagine ... A grade 2 foundation phase learner needs to be spoonfed.

Her comment reveals an understanding of learners as passive receivers of knowledge and constructs them as dependent, needing to be given work. The role of learning mediator and phase specialist envisaged in the documents (DHET 2011) is at odds with her own idea of "how to be" and "how to act" like a teacher (Sachs 2005:15).

Rather than address these different identity constructions, the workshops appear to cover pedagogical practices without engaging teachers' beliefs or the theories underpinning desirable practices. This is made evident by Mrs L feeling that she was unable to articulate her views on spoonfeeding in the workshop. If the mode of delivery for a workshop was aligned with its original definition, then its collaborative nature would have enabled teachers to engage in discussion. We suggest that the mode of the workshop and the environment created may in fact compromise teacher knowledge and confidence, and thus their professional development.

An inability to express opinions can create a sense of dependency. When asked what would assist her to provide quality teaching, Mrs L replied "more workshops". She stressed the importance of "the workshops, when they, they workshop us (our emphasis)." She talked about needing facilitators to provide more support:

then when they did the follow-up it's then that they help us. But if they don't come, I don't know whether what I'm doing it's the right thing. When they come they sit down like we do and then they ask me to give them my file and they page through. Then they see what I am doing. If I'm not doing something correctly then they correct me. Then they tell me that on this day, on this date, we'll be back to see whether you have improved, that thing helps a lot.

When Mrs L was probed further in the interview, one-on-one follow-ups appeared to be more valuable than the workshops. But she also noted that this type of support is infrequent and unreliable. We contend that when workshops do not adequately address the consequences of shifting teacher knowledge and practice, the result may be confusion. Confusion undermines the way teachers feel about themselves and their conditions of work (Jansen 2001) thus inadvertently reinforcing old practices, and creating a discourse of disempowerment. Mrs L's interview reveals a committed, caring teacher who is not sure how to be, act or understand her work (Sachs 2005:15). But, she was not averse to personalised attention to improve her understanding and classroom practice.

Miss G implementing workshop training

Miss G was teaching at a government primary school for three years. She was one of two grade R teachers, each with a class of 48 children. This study was conducted in 2009 when schools were following the Revised National Curriculum Statement (RNCS) (DOE 2005). It was during classroom observations and the subsequent interview that the particular incident relating to the statement "we are workshopped" took place.

Miss G presented a movement ring (similar to a physical education lesson) to all the grade R children. She took approximately 70 children onto the rather sparsely grassed playing field. On a hot November morning the hatless children participated in this ring, which lasted for over 45 minutes - a long time for any teacher-guided grade R activity. Miss G instructed the children to make a ring by holding hands and forming a large circle of which she was part. Because of the location (outdoors) and the size of the ring, it was very difficult for the children to hear and therefore follow any instructions. The children did their best to follow, often copying other children. There was no break between the different activities and children were not really given sufficient time to explore any of the suggested movements fully. Many children became restless and inattentive, some started crying and others ceased to participate. But the ring carried on until its planned completion. There were enough different activities to form the basis of a term's movement rings; especially if concepts and skills inherent in each activity were fully explored. For example, this movement ring included creative dance, locomotor and non-locomotor movements, educational gymnastics, as well as music, which are all components of an early childhood programme.

It was during the interview (when probing aspects relating to curriculum development) that Miss G made a remark in relation to a workshop held in her district that she had recently attended. She commented: "We were workshopped with LO4" (Learning Outcome 4). Initially it was difficult to place the remark in context, because all eight designated learning areas comprising the RNCS (DOE 2005) had a range of learning outcomes. When asked which learning area she was referring to she could not name it. After further probing, Miss G said this outcome was related to the movement ring. She was asked if she was referring to the Life Orientation learning area (in this learning area, physical development was described as the number 4 learning outcome). She could only repeat that, "they said we should do these things to meet LO4". She then stated, "at the workshop we [grade R teachers] have been shown many different movement activities that we can do with the children". It transpired that Miss G had incorporated every activity that had been demonstrated at the workshop into the observed movement ring.

Based on her account, the workshop's aim was to support and improve her practice and appears to have specifically met three roles of the teacher educator (phase specialist, learning mediator and interpreter and designer of learning programmes and materials) (DHET 2011).

From the observation and interview it is apparent that Miss G is struggling to meet these roles. Her inability to connect LO4 to the curriculum indicates her lack of understanding of the curriculum as a phase specialist. Therefore the workshop was seemingly not successful in supporting teacher professional development. Miss G also did not appear to have a deep understanding of the value of movement in early learning (Gallahue & Donnelly 2003). This would be expected phase knowledge for a grade R teacher. A lack or limited knowledge of the curriculum and understanding of how children learn (learning mediator) has a knock on effect, as her programme design took on a one-size-fits-all approach. These misconceptions cannot all be addressed in a single workshop.

This incident raises questions about workshop design and teacher needs:

• What are the assumptions made by workshop designers about what teachers should already know and understand? (Was a knowledge of movement in early learning assumed?)

• What are teachers' assumptions about the outcomes of workshops they attend? (Will they get practical advice for lessons or just information about curriculum changes?)

• How does the situation arise that a teacher can attend a workshop, yet not know what it was about? (Was the content not made clear, was the mode of delivery inappropriate or do teachers think there is no benefit and "zone out"?)

This is a teacher who attended a workshop, who felt that she had learned something. She showed some initiative and tried to implement it for an observed lesson. But it became apparent that the workshop had not made it clear how to explicitly sequence and pace these activities, i.e. how to appropriately implement the content over a period of time. Had the workshop been run in its correct format, these issues would likely have been addressed, even if not explicitly, because teachers would have planned together. It is possible that when teachers' experience of workshops is that which gets done to them they then do the same to their learners, falling back into a teacher-centred role.

What emerges for us from Miss G's experience is her misunderstanding of content appropriate for teachers and content appropriate for children. As a mode of delivery, workshops should be practical applications of theorised pedagogy. But when this term has come to mean a (mass) transmission model of curriculum change, not a model of refinement and improvement of practice for professional development, then confusion is understandable. We would argue that what teachers think they are getting (practical ideas for teaching) is not what facilitators are delivering (mass transmission), and this results in confusion where teachers like Miss G take the workshop content and transpose it directly into their teaching. Teachers' roles are undermined if they believe they are only at workshops to receive input.

In Mrs L's case a real workshop model would have interrogated the notion of spoonfeeding. She is not completely incorrect in her assumption; there are times when rote learning and spoonfeeding might be appropriate in the foundation phase, for example, when learning Dolch words. But it is not appropriate if it is the only pedagogical approach. If teachers are workshopped, rather than participants in a workshop, the knowledge they do have is silenced. Participants do not have a chance to explore and build on their understandings of good pedagogy. For an experienced teacher to feel she had no voice to express her opinion means that inexperienced teachers like Miss G might also not be in a position to ask for clarification, let alone express dissent. This has implications for the ways in which teachers feel about themselves professionally and emotionally (Jansen 2001), and how receptive they are to change.

Conclusion

What we have tried to show in our analysis of the statement "we are workshopped" and the examples of these two teachers' experiences are the consequences of being workshopped. There is repeated mundanity in the choice of tense, the use of the passive and the change of workshop into a verb. The meaning that results from this specific wording (Halliday 1994) reveals that teachers who used this statement construct themselves as dependent. The binary us/them construction of the department doing things to the teachers also points to a power relationship that potentially undermines, rather than supports, the kind of teacher the department holds as ideal. The experience of attending workshops by the teachers in our examples do not work to empower them or let their voices be heard, but reinforce a passive identity construction. There seems to be a gap between what is provided and what teachers need.

We are not suggesting that all workshops are transmission modes, or are ineffective in meeting the needs of teachers. Nor are we suggesting that the onus is solely on the department to empower teachers, because that would imply that teachers have no agency in negotiating their own professional identity. We are also not suggesting that all teachers lack agency, or lack agency all the time. What we do want to highlight is, what we think is, a disturbing trend captured in teacher discourse around professional teacher development. By believing things are done to them they undermine their ability to meet the roles of the teacher desired by the department.

The mode and content of current teacher professional development needs to be critically assessed. This assessment needs to take what teachers say about how professional development is offered seriously, because what they say conveys particular meanings with particular effects (Janks 2010). The effects of a teaching corps who use language to express a lack of agency is in no one's best interest.

References

Anning, A. 1997. The first years at school: Education 4-8. Milton Keynes: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Anning, A. 2006. Early years education: Mixed messages and conflicts. In Kassem, D., Mufti, E. & Robinson, J. (eds.). Educational Studies: Issues and Critical Perspectives, pp. 5-17. Berkshire: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Corpus of Contemporary American English. Workshop. Retrieved from http://corpus.byu.edu/coca/x.asp?w=1024&h=600 (accessed 12 July 2013).

Blackledge, A. & Pavlenko, A. 2002. Ideologies of language in multilingual contexts. Multilingua 21:2-3. [ Links ]

Carr, M. 2001. Assessment in early childhood settings: Learning stories London: Paul Chapman.

Commonwealth of Australia. 2005. In teachers' hands: Effective literacy teaching practices in the early years of schooling. Perth: Edith Cowan University.

Dixon, K. 2011. Literacy, power and the schooled body. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Day, C. & Kington, A. 2008. Identity, wellbeing and effectiveness the emotional contexts of teaching. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 16(1):7-23. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education (DBE). 2011. Minimum requirements for teacher education qualifications. Pretoria.

Department of Education (DOE). 2003. Personnel Administrative. Government Gazette, 24948 (21 February 2003).

DOE. 2000. Norms and standards for educators. Pretoria.

DOE. 2005. Revised national curriculum statement grades R-9. Pretoria.

Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET). 2011. Minimum requirements for teacher education qualifications. Pretoria.

Excell, L. 2011. Preschool teachers' perceptions of early childhood development and how these impact on classroom practice. (Unpublished PhD thesis). Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand. [ Links ]

Fairclough, N. 1989. Language and power. London: Longman. [ Links ]

Gallahue, D.L. & Donnelly, P.L. 2003. Developmental physical education for all children. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. [ Links ]

Gilmour, D. & Soudien, C. 2009. Learning and equitable access in the Western Cape, South Africa. Comparative Education, 45(2):281-295. [ Links ]

Hayes, D., Mills, M., Christie, P. & Lingard, B. 2006. Teaching and schooling make a difference: Productive pedagogies, assessment and performance. Sydney: Allen & Unwin. [ Links ]

Halliday, M. 1994. An introduction to functional grammar. (2nd edition). London: Edward Arnold. [ Links ]

Halliday, M. 1978. Language as social semiotic, pp. 183-193. London: Edward Arnold. [ Links ]

Janks, H. 2010. Literacy and power. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Jansen, J. 2001. Image-ining teachers: Policy images and teacher identity in South African classrooms. South African Journal of Education, 21(4):242-246. [ Links ]

MacDonald, C. & Burroughs, E. 1991. Eager to talk and learn and think. Cape Town: Maskew Miller Longman. [ Links ]

Newmann, F. & Associates. 1996. Authentic achievement: Restructuring schools for intellectual quality. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Sachs, J. 2005. Teacher education and the development of professional identity: Learning to be a teacher. In Denicolo, P. & Kompf, M. (eds.). Connecting policy and practice: Challenges for teaching and learning in schools and universities, pp. 5-21. Oxford: Routledge. [ Links ]

Welmond, M. 2002. Globalization viewed from the periphery: The dynamics of teacher identity in the Republic of Benin. Comparative Education Review, 46(1):37-65. [ Links ]

Wits School of Education. 2009. Implementation of the national curriculum statement in the foundation phase. Johannesburg.

Woodward, K. 1997. Concepts of identity and difference. In Woodward, K. (ed.). Identity and Difference, pp. 7-62. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Endnotes

1. We are not arguing that this is the first instance in which this statement is made. But, that it has been identified as occurring within this data set at this particular time. Further research would need to be done to establish when this statement entered into teachers' discourse.