Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Curationis

versão On-line ISSN 2223-6279

versão impressa ISSN 0379-8577

Curationis vol.37 no.1 Pretoria Jan. 2014

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/curationis.v37i1.1164

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Student nurses' perceptions of guidance and support in rural hospitals

Steppies R. RikhotsoI; Martha J.S. WilliamsII; Gedina de WetII

IDepartment of Nursing Science, University of Pretoria, South Africa

IISchool of Nursing Science, North-West University, Potchefstroom Campus, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Clinical guidance and support of nursing students in rural hospitals is a challenge for novice nurses, who rotate amongst accredited hospitals throughout the province for clinical exposure, and find themselves in an unfamiliar environment. Theory learned at the training college is integrated with clinical exposure at hospitals and supplemented through teaching by hospital staff. Nursing students complain about lack of support and guidance from professional nurses within the hospital, some feeling restricted in execution of their nursing tasks by professional nurses and other staff. Students perceived negative attitudes from clinical staff, a lack of clinical resources, inadequate learning opportunities and a lack of support and mentoring during their clinical exposure.

OBJECTIVES: This article describes perceptions of guidance and support of nursing students by professional nurses in a rural hospital and suggests guidelines for clinical guidance and support of nursing students.

METHOD: A qualitative, explorative, descriptive and contextual design was used. Two focus group interviews were employed to collect data from a sample drawn from level II nursing students from one training college in Limpopo Province, South Africa, on different days (n = 13; n = 10). Qualitative content analysis was used to analyse data.

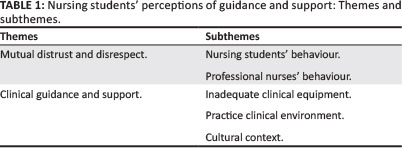

RESULTS: Three themes (mutual distrust and disrespect, hospital environment, and clinical guidance and support) and subthemes (student behaviour and staff behaviour) emerged.

CONCLUSION: Failure to support and guide nursing students professionally may lead to high turnover and absenteeism, resulting in students' refusal to be allocated to a rural hospital for clinical exposure. Proposed guidelines have been formulated for clinical guidance and support of nursing students at the selected rural hospital. The college and hospital management should foster collaboration between the college tutors and professional nurses to ensure adequate guidance and support of nursing students.

Introduction

There is a 'below the surface' tension between clinical staff of training institutions and nursing students from Limpopo College of Nursing. The clinical accompaniment, guidance and support process in a rural hospital was questioned by the students, who are unhappy about professional nurses' attitudes and behaviour. The training of nurses includes both theory (classroom learning) and clinical practice for successful application and integration of new learned knowledge (Bezuidenhout 2003:19). Nursing students should be allowed and supported to interact with clients and their families in any clinical practice environment, to stimulate and acquire critical-thinking, decision-making, psychomotor and affective skills (Stokes & Kost 2009:283).

There seems to be uncertainty about the responsibility for clinical accompaniment, guidance and support of nursing students within the South African context. The Nursing Act 2005 (Act No. 33 of 2005) (Republic of South Africa 2005) empowered professional nurses and midwives to assist, guide and support nursing students throughout their training, with the aim of developing competent, independent nurse practitioners by creating a conducive environment for learning (Bastable 2003:13; Republic of South Africa 2005:34). That professional nurses have an educational role to facilitate development of nursing students both academically and personally is supported by Bond and Holland (1998:12). Stokes and Kost (2009:287) assert that the clinical tutor as a role model plays a crucial role for the successful clinical understanding of nursing students by sharing their clinical experience and knowledge of theory for the practice of nursing and the profession.

Four different levels of nursing students (levels I-IV) are placed at the hospital, with one clinical tutor responsible for a group of about 50 students, allocated in different disciplines. The nursing students do not receive adequate accompaniment, guidance and support during their clinical learning and practice due to the shortage of professional nurses at the rural hospital (Rikhotso 2010:51). The rural hospital where the nursing students obtain clinical exposure and learning posed a challenge to the professional nurses, due to the imbalance of work between patient care and providing guidance and support to nursing students. Lekhuleni, Van der Wal and Ehlers (2004:9) are of the opinion that clinical accompaniment, supervision, guidance and support for nursing students should be shared by a multidisciplinary team including nurse educators, peer group, professional nurses, doctors, dieticians and other allied health professionals.

The clinical professional nurses feel that providing guidance and support for the students is an extra workload which is burdened by understaffing, the impact of poverty and debilitating diseases such as HIV and/or AIDS, tuberculosis and malnutrition. Due to the shortage of professional nurses in the wards, nursing students' guidance and support becomes less important, and they become incompetent employees with inadequate skills as they are tasked to cover the shortage in patient care (Mhlongo 1996:29; Rikhotso 2010:51).

Nursing students are trained by Limpopo College of Nursing and allocated for clinical exposure at accredited hospitals within Limpopo. When this study was conducted the college was using the block system for students to rotate between theoretical and clinical learning settings. During clinical placement the nursing students find themselves in an unfamiliar environment and location on a monthly basis, and some suffer psychologically as the hospital and surroundings are new, with little or no guidance and support within the hospital.

This article reports on a study conducted in a rural area surrounded by underdeveloped villages dependent on farming, 30 km from the nearest town, with taxis and buses the only mode of public transport. The area is dominated by two cultural, ethnic groups (Tshivenda and Xitsonga), and is traditionally conservative. According to literature reviewed by the researcher, limited research has been conducted in Limpopo regarding guidance and support during clinical exposure of nursing students from the Nursing College in this setting. This article explores the perceptions of nursing students in a specific rural hospital, and proposes guidelines for effective clinical guidance and support in similar settings.

Research objectives

The researcher was guided by the following research question: 'How do nursing students perceive clinical guidance and support during clinical exposure?'. The research purpose was achieved using the following objectives: to explore and describe the perceptions of nursing students with regard to clinical guidance and support at the rural hospital; and to suggest guidelines for clinical guidance and support of nursing students.

Definition of key concepts

Professional nurse: A person registered as such in terms of section 31 of the Nursing Act (Act 33 of 2005) (Republic of South Africa2005) in order to practice nursing or midwifery.

Nursing student: A learner nurse registered as such in terms of section 32 of the Nursing Act (Act 33 of 2005) (Republic of South Africa2005) to practice under Regulation R425.

Perception: The sensory experience of the world around the person using the five senses (smell, sight, hearing, touch and taste) that influence the way that person thinks and behaves (Wehmeier 2005:513).

Guidance: Influence of a person who shows the way by leading, advising and being a role model to the neophyte others.

Literature review

The literature review set out to review studies that have been done on the perceptions of nursing students regarding clinical accompaniment, guidance and support at a rural hospital. According to Bjørk et al. (2013:2) the clinical practice environment or wards have a positive influence on the behaviour and attitudes of nursing students towards that hospital, although some students experienced a negative influence (Mabuda, Potgieter & Alberts 2008:19). These negative aspects also hinder guidance and support of nursing students whilst in the clinical area for clinical exposure. Tension was created between the students and the clinical staff due to mistrust and the poor relationship and lack of support which exists at the institution. The nursing students are regarded as extra assistants, a 'pair of hands' as it were, resulting in less than satisfactory clinical guidance and support (Mhlongo 1996:29).

Lekhuleni et al. (2004:9) asserted that clinical guidance and support of nursing students should be shared by all responsible for the students' learning and professional development. Some of the clinical staff members at public hospitals perceive clinical accompaniment, guidance and support as not being their task (Mtambo 2009:28). The nursing student should be afforded an opportunity to be guided and supported towards professionalism, thus enabling the nurse to practise duties accountably and responsibly within set standards (Mogale & Moleki 2011:39).

There are some factors that may contribute to inadequate clinical guidance and support for nursing students, and these include large numbers of students in one setting, shortage of personnel, lack of confidence of professional nurses and students, inaccessibility of students and undesirable characteristics of the students (Siggins Miller Consultants 2012:10). Limited research has been done relating to ethnicity, insults, and the dilapidated students' residence (where reptiles such as snakes are found), the shortage of resources in the students' residence and the clinical practice of caring for patients during the placement and accompaniment, guidance and support of nursing students. Overpopulation in the students' residence remains an issue, with four to eight nursing students occupying one cramped room, with problems such as 'roof leakages' and 'poor electric lights' reported (Rikhotso 2010:53).

Research method and design

Design

A qualitative, explorative, descriptive and contextual research design was used to explore and describe the experiences of nursing students regarding clinical guidance and support in a rural hospital.

Sampling and sample size

The population consisted of all level II nursing students from one college and placed in one rural hospital in Limpopo Province, South Africa, for exposure to clinical work and learning under guidance and support of professional nurses. A purposive sampling technique was used to select a sample from the study population. The participants were contacted through the nursing college and the management of the specific hospital. Two focus groups were interviewed in two different sessions on different days. Thirteen participants formed focus group one (n = 13), with 10 (n = 10) participants forming focus group two in the second week after provisional data analysis due to insufficient data.

Data collection method

Two focus group interviews were done for the main study. The researcher used one central question: 'Describe your perception on clinical accompaniment, guidance and support in this hospital', followed by probing during the interview. The interview was audio-recorded and the tapes stored in a safe. Data collection was discontinued after data saturation had been reached and participants were repeating data that had been obtained from previous or other participants.

Data analysis

The participants were interviewed in English because it is the medium of instruction for nursing students. Verbatim transcriptions of audio-taped data were done by the researcher prior to data analysis. Data were analysed using qualitative content analysis as described by Graneheim and Lundman (2004:106).

Results

The findings were analysed and discussed according to the process of qualitative content analysis as described by Graneheim and Lundman (2004:106), including condensed meaning units, subthemes and themes.

The themes and subthemes identified from the transcribed data are listed in Table 1.

Mutual distrust and disrespect

Disrespectful, mean and aggressive behaviour results in a negative relationship between the nursing students and the hospital staff, particularly professional nurses. The negative attitude of the professional nurses at hospitals reduces the nursing students' respect and trust for them (Leape et al. 2012:1). This creates incivility within the clinical environment where students are exposed to integrating theory into practice, resulting in inadequate guidance and support provision by professional nurses.

Nursing students' behaviour

The negative behaviour of some nursing students, by being disrespectful to the professional nurses, deprives hard-working students of their clinical exposure and educational experiences. The students shift the blame to staff members of the hospital, due to ineffective clinical guidance and support by clinical tutors and professional nurses. This disruptive behaviour or conduct of nursing students may be directed at everyone in the ward, including patients and their families, and is inappropriate (Leape et al. 2012:2) in the profession.

One of the nursing students justified her disrespectful behaviour as follows: 'We undermine the sisters in the ward; we do not follow their instructions, especially sisters with one bar. I personally think they do not have knowledge to feed me.'

Professional nurses' behaviour

The nursing students had mixed perceptions about the behaviour of professional nurses regarding supervision, guidance and support in their learning at the clinical area. Some wards' staff members were reported to be 'joy-stealers' by the nursing students, as they are robbed of their productivity, feelings of belonging and the desire for learning and developing professionally. However, this was not the case in all of the wards. In some wards, as reported by the nursing students, staff members made profane remarks and used abusive language which is inappropriate and demeaning, and were openly hostile. This is evident in the following quote:

'We are not treated well in this hospital and they say we are lazy. They tell us that we do not know the work … we think we are smart, we are going to die of HIV. Sisters cannot give me an answer if I ask for help … she told me to read from the book … I conclude that the sister does not know.' (Focus group [FG] 1, participant [P] 3)

Clinical guidance and support

The nursing students perceived the clinical rural hospital where they were supposed to obtain guidance and support from professional nurses as not conducive to learning. This was due to old-fashioned and insufficient as well as malfunctioning medical and nursing equipment, as well as a shortage of staff to guide and support them during their learning.

Inadequate clinical equipment

The students experienced a lack of clinical equipment for patient care, such as Baumanometers to measure the blood pressure of patients (Magobe, Beukes & Muller 2010:11), and professional nurses and their staff compromise by borrowing from other wards. Thus students felt that the clinical environment was not being conducive to learning and caring for the patients, as evident by the quote below:

'Most wards where I worked do not have adequate patient monitoring machines. Here there are no BP [blood pressure] machines, thermometers and linen for patients. There are no screen/curtains in some wards, curtain holders are there … ask … sent for mending one month ago.' (FG1, P4)

Practice clinical environment

The nursing students experienced mixed feelings about the rural clinical environment during their learning. They had both negative and positive perceptions, depending on how they viewed the hospital and the staff. What one student perceives as a learning opportunity, another may perceive differently. Some nursing students complained of being blamed for wrong actions within the wards by professional and staff nurses, who failed to guide, assist or involve them on ward routines.

This is how one nursing student expressed her perception:

'I did not know what to do … she told me to improvise.' (FG2, P2)

'I learnt a lot in this hospital; doctors are so helpful, the sisters in some wards are always ready to teach and ensure that we meet our objectives. I become confused and lost interest due to the neglect we receive from the ward staff. Others [staff] are not welcoming you, no introducing each other. First arrive in the ward, we are happy, but at the end we are not happy because they are not treating us well.' (FG1, P6)

'There is this sister who has the natural hatred, I see her for the first time but she hates me or all the students from the college.' (FG1, P3)

Cultural context

The nursing students expressed negative perceptions regarding the ethnocentrism they experienced in the clinical environment:

'They call us names … they say we are here to take their husbands and boyfriends, especially us female students.' (FG2, P4)

'They do not like other cultures like Pedi-speaking.' (FG1, P4)

'The college treats us as students, but the hospital segregates us; we are not treated the same like those who speak the language of the sister supervising the ward. Racism is practised in some wards.' (FG1, P4)

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from North-West University (Potchefstroom Campus). The Ethics Committee of the Limpopo Provincial Government's health department issued a permission letter for entry into the institution where the study was conducted (the institution gave verbal permission on the basis of approval by the Ethics Committee of Limpopo Provincial Government). Participants gave informed consent after thorough explanation of the nature and extent of the study by the researcher. The audio tape-recordings were kept under lock and key by the researcher after verbatim transcription of the interviews.

Trustworthiness

In this study the evaluation of data quality was ensured by using Lincoln and Guba's (1985:290) methods, which include credibility, confirmability and transferability. The researcher ensured credibility by prolonged engagement with the participants, planning the study with experts and use of a similar question for all participants. Confirmability was assured by the second researcher, who assisted with analysis and coding, audio-recording of interviews and records kept for the audit trail. Thorough descriptions of the findings were provided to ensure transferability.

Discussion

According to the constructivist approach to teaching and learning (Klopper 2001:103-104; Bruner 1996:42), nursing students should take responsibility for their own learning through active participation and constructing new knowledge. The clinical environment in which nursing students are placed for clinical learning through exposure and experience should have an invitational, positive attitude, create a mutual trusting relationship with all staff members, including students, and accept responsibility for the success of the learning process.

This article reports that the institution where the main study was done lacks the characteristics of the teaching-learning relationship, based on the nursing students' perceptions of clinical guidance and support. The relationship which exists between students and professional nurses does not provide guidance and support for learning due to mutual disrespect and mistrust, resulting in offensive behavioural patterns by both students and staff.

The first author of this article worked in the same rural institution where the study was conducted for many years, and the findings and reports from the literature are true as discussed. The experience of nursing students in the context is true, although somewhat exaggerated. Some district hospitals (level 1) are understaffed (in terms of both doctors and nurses), and have a shortage of clinical equipment as well as drugs due to challenges beyond the scope of the particular hospital's professional nurses.

These challenges adversely affect patient care by causing substitution of safe and effective nursing care and medication with alternative treatments; compromising nursing and medical procedures; or resulting in medical errors as students 'work' without guidance (Hart & Rotem 1994:31; Ventola 2011:740). Most hospital wards are managed by one professional nurse per shift, and thus it becomes difficult for them to take full responsibility for students' guidance and support in learning.

District hospitals are the catchment centres for poor communities, who suffer from chronic and debilitating illnesses, operating with constrained budgets and with a lack of clinical equipment and expert professionals. That rural hospitals or district hospitals try to provide patients with the optimal quality of care whilst simultaneously tackling challenges due to their often remote geographical area and limited resources (human, financial and equipment) is supported by American Hospital Association Trendwatch (2011:2).

Students enjoy learning and working under the guidance and support of a knowledgeable professional nurse for their effective professional development (Beukes, Nolte & Arries 2010:4). A shortage of staff, high bed occupancy, high student ratio and lack of clinical equipment burdens the overstretched professional nurse, thus giving little or no opportunity to provide attention to guide and support nursing students (Mabuda et al. 2008:20).

Jirwe, Gerish and Emami (2009:23) allude to the fact that lack of communication and cross-cultural care encounters are problematic in care of patients from a different background to the professional nurses. This communication problem between cultural and ethnic groups may be transferred to nursing students, and they can experience difficulties in communicating with patients with whom they do not share a common language (Boykins & Carter 2012:2), putting patients at risk in their care.

Interpersonal communication skills should be practised and implemented by all nurses throughout the training of students to embrace the cultural diversity of the South African rainbow population; this has a therapeutic effect on an individual and the clinical environment. The clinical learning opportunities and clinical guidance and support of nursing students, hampered by limited clinical equipment and other resources, poor interpersonal relationships and ineffective communication, may be complicated by ethnocentrism in some hospitals. For effective communication, professional nurses, nursing managers, clinical tutors and the college management should involve the nursing students, as a form of learning guidance in preparation of future competent professional nurses who care for diverse patients within society.

Conclusion

Many articles have been written about the experiences and perceptions of nursing students regarding clinical placement and accompaniment in the clinical setting. The study on which this article is based explored and described the experiences of nursing students in a specific rural hospital. The researcher proposes guidelines, supported by the literature, for the clinical guidance and support of nursing students during their clinical exposure and learning in hospitals. The proposed guidelines include: Creation of a context conducive to a learning environment in the clinical practice by means of clarity on mutual expectations; and the provincial government to launch an enquiry about the status of hospitals' physical infrastructure, maintenance and availability of essential patient equipment.

The findings of the literature review showed that students perceive clinical guidance and support differently, namely negatively or positively. The nursing students experienced lack of support, inadequate mentoring and guidance, isolation from clinical activities, an inhumane attitude by clinical staff, a poor clinical environment and many other aspects as hindering students' learning. Stokes and Kost (2009:283) describe clinical practice for nursing students as any place where they interact with the patient and his or her family or community. During this learning by interaction with the clients the nursing students integrate theory into practice. Support and guidance in this regard should be given by the professional nurses and other health professionals within the hospital (Bezuidenhout 2003:19).

The study which this article reports on was explorative in nature and held in a specific setting; therefore the results cannot be generalised. Evidence from literature and this study demonstrates the need for the college and hospital management of all training institutions to provide placement and accompaniment, guidance and support guidelines for effective learning in the clinical setting.

The findings as described here demonstrate the need to implement the proposed guidelines as soon as possible to avoid nursing students from forming a negative attitude towards clinical placement in this setting. The nursing students should also be supported throughout their training during the rotation amongst the hospitals, to gain more knowledge and skills with or without adequate clinical resources.

This article will assist readers (health professionals - i.e. nursing students, college tutors, professional nurses and hospital and college managers) to be aware of the impact that the clinical setting, guidance and support have on the education and learning of nursing students. This article contributes to the understanding of why nursing students taking part in the current research were reluctant when allocated to certain hospitals. The management of the college and hospitals should be aware of and understand the behaviour of nursing students in this setting, assist them to develop professionally and provide ways to deal with challenges at the hospital. Good interpersonal relationships should be promoted amongst staff, irrespective of the status of the nurse that acts as facilitator, mentor and supporter in the clinical environment.

Acknowledgements

Dr Petra Bester (North-West University) acted as a co-coder, and Dr Marthyna Williams (North-West University) is thanked for assisting in the study. I acknowledge the contribution of the participants and the services of the editor (Dr Pieter van der Westhuizen) and Mrs Jackie Viljoen, Stellenbosch University, who assisted in writing this article.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationship(s) that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

S.R.R. (University of Pretoria) prepared and wrote the manuscript. M.J.S.W. and G.D.W. (North-West University) assisted with data analysis and discussion of results. Proofreading was done by M.D.P. (University of Pretoria), and the final draft was compiled by S.R.R.

References

American Hospital Association Trendwatch, 2011, The opportunities and challenges for rural hospitals in an era of health reform, American Hospital Association, North Mississippi. [ Links ]

Bastable, S.B., 2003, Nurse as Educator: Principles of teaching and learning for nursing practice, 2nd edn., Jones and Barlett, Sandbury, MA. [ Links ]

Beukes, S., Nolte, A.G.W. & Arries, E., 2010, 'Value-sensitive clinical guidance and support in community nursing science', Journal of Interdisciplinary Health Sciences 15(1), 4. [ Links ]

Bezuidenhout, M.C., 2003, 'Guidelines for enhancing clinical supervision', Health SA Gesondheid 8(4), 20. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hsag.v8i4.142 [ Links ]

Bjørk, I.T., Berntsen, K., Brynildsen, G. & Hestetun, M., 2013, 'Nursing students' perceptions of their clinical learning environment in placements outside traditional hospital settings', Journal of Clinical Nursing 23(19), 2958-2967. [ Links ]

Bond, M. & Holland, S., 1998, Skills of clinical supervision for nurses: A practical guide for supervisees, clinical supervisors and managers. Supervision in context, Open University Press, London. [ Links ]

Boykins, A. & Carter, C., 2012, 'Interpersonal and cross-cultural communication for advance practice registered nurse leaders', Journal of Advanced Nursing Practice 11(2). [ Links ]

Bruner, J., 1996, The culture of education, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. [ Links ]

Graneheim, U.H. & Lundman, B., 2004, 'Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness', Nurse Education Today 24(2), 105-112. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001 [ Links ]

Hart, G. & Rotem, A., 1994, 'The best and the worst: Students' perception of clinical education', Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing 11, 26-33. [ Links ]

Jirwe, M., Gerish, K. & Emami, A., 2009, 'Student nurses' perceptions of communication in cross-cultural care encounters', Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 24(3), 436-444. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2009.00733.x [ Links ]

Klopper, H., 2001, Nursing education: A reflection, Amabukhu, Lynwood Ridge. [ Links ]

Leape, L.L., Shore, M.F., Diestag, J.L., Mayer, R.J., Edgman-Levitan, S., Meyer, G.S. & Healy, G.B., 2012, Perspective: A culture of respect, part 1: The nature and causes of disrespectful; behaviour by physicians, Academic Medicine 87(7), 1-8. [ Links ]

Lekhuleni, E.M., Van Der Wal, D.M. & Ehlers, V.J., 2004, 'Perceptions regarding the clinical guidance and support of nursing students in the Limpopo Province', Health SA Gesondheid, 9(3), 15-27. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hsag.v9i3.168 [ Links ]

Lincoln, Y.S. & Guba, E.A., 1985, Naturalistic inquiry, Sage, Thousand Oaks, Calif. [ Links ]

Mabuda, B.T., Potgieter, E. & Alberts, U.U., 2008, 'Student nurses' perceptions during clinical practice in the Limpopo Province', Curationis31(1), 19-27. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/curationis.v31i1.901 [ Links ]

Magobe, N.B.D., Beukes, S. & Muller, A., 2010, 'Reasons for students' poor clinical competencies in Primary Health Care: Clinical nursing, diagnosis treatment', Health SA Gesondheid 15(1), 6. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hsag.v15i1.525 [ Links ]

Mhlongo, C.S., 1996, 'The role of unit sisters in teaching nursing students in Kabuli hospitals', Curationis 19(3), 28-31. [ Links ]

Mogale, L.C. & Moleki, M.M., 2011, 'Student nurses' perceptions of their clinical guidance and support', MCur. dissertation, University of South Africa. [ Links ]

Mtambo, S.N., 2009, 'Student nurses' perception of clinical guidance and support in a public hospital in Gauteng Province', MCur. dissertation, University of South Africa. [ Links ]

Rikhotso, S.R., 2010, 'Clinical accompaniment in a rural hospital: Student and professional nurses' experience', MCur. thesis, Division of Nursing, North-West University. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa, 2005, Nursing Act (Act 33 of 2005), Government Printer, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Siggins Miller Consultants, 2012, Promoting quality in clinical placements: Literature review and national stakeholder consultation, Health Workforce Australia, Adelaide. [ Links ]

Stokes, L. & Kost, G. 2009, 'Teaching in the clinical setting', in D.M. Billings & J.A. Halstead, Teaching in nursing: A guide for faculty, pp. 282-284, Elsevier Saunders, St Louis, Miss. [ Links ]

Ventola, C.L., 2011, 'The drug shortage crisis in the United States: Causes, impact, and management strategies', Pharmacy & Therapeutics36(11), 740-757. [ Links ]

Wehmeier, S., 2005, Oxford advanced learner's dictionary, Oxford University Press, Oxford [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Richard Rikhotso

112 Erasmus Street

Polokwane 0699

South Africa

Email: richard.rikhotso@up.ac.za

Received: 27 Mar. 2013

Accepted: 28 July 2014

Published: 19 Nov. 2014