Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Curationis

On-line version ISSN 2223-6279

Print version ISSN 0379-8577

Curationis vol.37 n.1 Pretoria Jan. 2014

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners' ideas and needs for supervision in private practice in South Africa

Annie M. Temane; Marie Poggenpoel; Chris P.H. Myburgh

Department of Nursing Science, University of Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Supervision forms an integral part of psychiatric nursing. The value of clinical supervision has been demonstrated widely in research. Despite efforts made toward advanced psychiatric nursing, supervision seems to be non-existent in this field.

OBJECTIVES: The aim of this study was to explore and describe advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners' ideas and needs with regard to supervision in private practice in order to contribute to the new efforts made in advanced psychiatric nursing in South Africa.

METHOD: A qualitative, descriptive, exploratory, and contextual design using a phenomenological approach as research method was utilised in this study. A purposive sampling was used. Eight advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners in private practice described their ideas and needs for supervision during phenomenological interviews. Tesch's method of open coding was utilised to analyse data. After data analysis the findings were re-contextualised within literature.

RESULTS: The data analysis generated the following themes - that the supervisor should have or possess: (a) professional competencies, (b) personal competencies and (c) specific facilitative communication skills. The findings indicated that there was a need for supervision of advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners in private practice in South Africa.

CONCLUSION: This study indicates that there is need for supervision and competent supervisors in private practice. Supervision can be beneficial with regard to developing a culture of support for advanced psychiatric practitioners in private practice and also psychiatric nurse practitioners.

Introduction

Advanced practice and the advanced practitioner can be considered to be inextricably linked by the common theme of advanced knowledge and skills (Christensen 2011:873). Globally, advanced practice nurses are viewed as experts in their respective domains, being engaged in activities that extend beyond the narrow application of technically-complex procedures (Canadian Nurses Association 2008:22; Hamric, Spross & Hanson 2009:78; Schober & Affara 2006:12). Sheer and Wong (2008:204) describe advanced practice nursing as being an umbrella term signifying nurses that practise at a higher level than do traditional nurses. Broom et al. (2008:131) indicate that advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners possess specialised clinical skills and bring with them expertise in communication, facilitation, relationship dynamics and interpersonal and organisational systems.

Advanced practice nursing is new in South Africa, even though there are professional nurses who are trained by higher education institutions to a master's or doctoral level with the focus on a specialised discipline such as psychiatric nursing. Professional psychiatric nurses have been registered with the South African Nursing Council (SANC) under R212 of the Nursing Act 50 of 1978 since 1993 (South African Nursing Council 1993). However, the terminology in advanced practice nursing with regard to professional nurses being advanced practitioners is still currently being clarified by delegated subcommittees in the SANC. Upon attaining their qualification, these advanced professional nurses register with the SANC for an additional qualification. It is not clear as yet just how their expertise is utilised in the private practice or hospital settings.

Lakeman (2000:90) defines expertise as the capability of nurses to express the scope of practice within their particular workplace. The scope of practice for advanced nurse practitioners encompasses a broad range of activities. These include advanced health assessment, diagnosis, disease management, health education and promotion, referral ability, prescription of diagnostic procedures, medications and treatment plans, admitting and discharging privileges, patient caseload management, collaborative practice, evaluation of healthcare services and research (Fulcher 2011:17; Pulcini et al. 2010:32). The scope of practice for advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners over and above what is mentioned includes psychotherapy for individuals, groups, families and communities; prescription of psychiatric treatment; and ordering. Their scope of practice furthermore includes consultant liaison, assisting in clinical supervision for other mental health team members and interpretation of diagnostic and laboratory testing; however, this depends on the regulations that govern their actions (Kneisl, Wilson & Trigoboff 2004:20). There is much debate about the what, when and why regarding when advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners should or should not conduct psychotherapy. Wheeler (2005:151) argues that psychotherapy is an important competency that all psychiatric nurse practitioners must attain in preparation for advanced psychiatric nursing.

In South Africa, there is no clear legislation that defines the scope of practice for advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners, either in private practice or in hospital settings. However, the SANC has drafted a position statement for advanced practice nursing wherein they indicate that it should be distinguished into two levels: the clinical nurse specialist and the advanced nurse practitioner. Currently, these specialists can only be registered for an additional qualification with the SANC as part of post-basic training. A clinical nurse specialist is defined as an individual having a qualification in the area of specialisation, as well as in-depth knowledge and expertise that enable her to focus on facility care and work closely with medical officers on a consultative basis. An advanced nurse practitioner is defined as a person who focuses on primary care, health assessment, diagnosis and treatment (South African Nursing Council 2012:1). Kucera, Higgins and McMillan (2007:44) report that there is still debate about the roles and functions of an advanced practice nurse, which largely emphasises inconsistencies in advanced nursing practice. Lakeman (2000:89) argues that the advancement of nursing has become tied to the quest for recognition of nursing as a profession. The development of clearly-defined roles for nurses may provide a platform from which to market nursing and further develop the agenda of professionalisation.

As independent nurse practitioners in private practice, advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners assume independence in using complex skills to understand and operationalise interpersonal communication and other theories as they relate to client care and professional practice (Hines-Martin & Robinson 2006:293). However, as they are in private practice, there is significant risk to advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners of becoming isolated in their work (Savic-Jabrow 2010:231). Whyte (quoted in Savic-Jabrow 2010:231) points out that it is easy when one is isolated to experience difficulty in accessing support, even when it is available, because one has had to develop working practices that rely heavily on 'self' rather than 'other' as a means of achieving restorative gain. The literature indicates that independent practitioners can benefit from an ongoing learning process such as supervision, since supervision is an essential element in the professional development of advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners (Binnie 2011:584; Hines-Martin & Robinson 2006:294).

Hawkins and Shohet (2006:5) emphasise that it is necessary to have a support system that is most appropriate to an independent practitioner's working situation. The challenge is that supervision beyond graduation is not a common practice and sometimes ends altogether after qualification (Hawkins & Shohet, 2006:5; Savic-Jabrow 2010:229). It is well documented in international literature that supervision is a supportive method of professional reflection and counselling, enabling professional workers to acquire new professional and personal insights through their own experiences (Bedward & Daniels 2005:54; Binnie 2011:585; Cleary & Freeman 2006:995; Hines-Martin & Robinson 2006:293; Lakeman 2000:90; McKenna et al. 2010:267; Zorga 2002:266). Hawkins and Shohet (2006:5) point out that supervision can be an important part of taking care of oneself and remaining open to new learning; it can also become an indispensable part of the helper's well-being, ongoing self-development, self-awareness and commitment to development. The educational preparation of advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners is two academic years. This curriculum of advanced psychiatric nursing differs from one higher education institution to the next. The first year of study prepares advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners in four advanced roles in clinical practice: care provision and management, professional practice, consultation and leadership and personal development and quality of care. The second year of study consists of preparation in research approaches and methods, evaluation, analysis and interpretation of research.

With a qualification at an advanced level, advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners have an opportunity to register for private practice with the Board of HealthCare Funders (BHF) to provide services to private clients. Working in private practice means that the advanced psychiatric nurse practitioner is an independent practitioner. As such, advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners work in isolation to set up business plans, marketing strategies and seeing clients for consultation on a daily basis, all of which can bring about challenges with regard to the efficient running of a private practice. Being in private practice, advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners can benefit from ongoing feedback, which will assist them in their professional development and recognition and in the avoidance of pitfalls such as counter-transference (Hines-Martin & Robinson 2006:293).

Problem statement

Supervision is a neglected issue pertaining to advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners in sustaining their therapeutic abilities. Psychiatric nurses are trained and supervised at a postgraduate level to develop clinical skills in individual, group and family psychotherapy.

Whilst the value of clinical supervision has been demonstrated in research, there is little research about how advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners sustain therapeutic abilities and whether they engage in supervision when in private practice. Being isolated in private practice can bring about issues such as burnout and stress. There is relatively little known about the support needs of advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners. Furthermore, there is little information available about advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners' need for and ideas on supervision in private practice in South Africa. The research questions that arose from the problem statement were: 'What are the advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners' ideas and needs with regard to supervision in private practice in South Africa?' and 'What recommendations can be made with regard to the supervision of advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners in private practice in South Africa?'

Aim of the study

The aim of this study was to explore and describe advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners' ideas and needs regarding supervision in private practice and to make recommendations regarding the supervision of advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners in private practice in South Africa.

Definitions of key concepts

Mental health is defined as the 'state of well-being in which the individual realises his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community' (World Health Organization 2001:1).

An advanced psychiatric nurse practitioner is a nurse practitioner who has acquired an expert knowledge base, complex decision-making skills and clinical competencies for expanded practices, the characteristics of which are shaped by the context and/or country in which he or she is certified to practise (Schober & Affara 2006:12).

Supervision is a formal process that provides professional support to enable practitioners to develop their knowledge and competence in order to assume responsibility for their own practice and to promote service users' health outcomes and safety (Binnie 2011:584; Hines-Martin & Robinson 2006:293; McKenna et al. 2010:267).

Private practice refers to the workplace of a professional person who works independently and is not an employee (TheFreeDictionary 2013).

Research design

A qualitative, exploratory, descriptive, and contextual design was used in this study. The main aim of this design is to give an in-depth description of the phenomenon under study (Creswell 2007:57). This is a suitable approach for this study, since little is known about advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners' ideas and needs for supervision and how they sustain their therapeutic abilities in private practice. Kilcullen (2007:1032) maintains that this design is suitable when the topic studied is new or where there is a dearth of facts in previous information. A constructivist philosophy of science was adopted in this research in that the assumption is that there are many truths and not only one truth.

Research method

A phenomenological approach was implemented in this research. A phenomenological approach aims to understand and interpret the meaning that participants give to experiences in their everyday lives. The design gives a descriptive passage that describes the essence of what the participants experienced and how they experienced it (Creswell 2007:57).

Population and sampling

The population of this study was advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners in private practice who were sampled purposively. Purposive sampling is a non-probability method of sampling in which the researcher selects participants who are considered to be typical of the population (LoBiondo-Wood & Haber 2009:584; Polit & Beck 2012:517). Kilcullen (2007:1032) maintains that purposive sampling is utilised in order to recruit a sample of participants who have information and experience that the researcher wants to elicit. Certain advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners in private practice were selected by the researcher on the basis that they were willing to participate in sharing their views on supervision and had been active in private practice for two to three years. Data saturation was achieved after eight interviews with participants, as evidenced by repeating themes, and no new information emerged from the interviews. Data saturation refers to the point when the information being shared with the researcher becomes repetitive and new data yields redundant information (LoBiondo-Wood & Haber 2009:584; Polit & Beck 2012:742).

Data collection

Data were collected from advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners by conducting phenomenological interviews until data saturation was achieved. Phenomenological interviews are in-depth interviews used to explore and describe the ideas and needs of the interviewees; in this case, advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners. Rubin and Rubin (2012:3) state that this type of interview assists the researcher in exploring in detail the experiences, motives and opinions of participants and in learning to see the world from a perspective other than his or her own.

Data were collected by a skilled interviewer who has experience in qualitative research and use of facilitative communication skills. Informed consent to record the interviews was requested from the advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners. It was indicated that the purpose of recording the interviews was to capture data for analysis. The researcher arranged interview times with the advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners and confirmed with them by email.

The practitioners were prompted by the open-ended statement: 'Tell me about your ideas and needs for supervision'. Communication skills such as reflection, paraphrasing, minimal responses and clarification were used in order to facilitate the interview process. The interviews lasted for approximately 45 minutes and were audio taped. Field notes were also compiled after each interview so as to describe the underlying themes and dynamics during the interview.

Data were collected until there was a repetition of themes about the participants' ideas and their need for supervision. Similar descriptions were reported repeatedly, indicating saturation of data in the study.

Data analysis

The recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed for repetitive themes. Data were analysed according to Tesch's method of open coding (quoted in Creswell 2013:191) and themes were formulated. An independent coder experienced in the field of qualitative research was used to code the data. A consensus meeting was held between the researcher and the independent coder in order to verify results.

Trustworthiness

Trustworthiness was ensured by utilising Lincoln and Guba's model (De Vos et al. 2011:419-421; Polit & Beck 2012:584-597; Shenton 2004:73). In this study, the strategies utilised to ensure trustworthiness were credibility, transferability, dependability and conformability. To enhance credibility, the researcher held discussions with other advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners who did not take part in the research but were interested in supervision. The researcher wrote field notes throughout the research process in order to reflect on the process. Triangulation was achieved through the use of in-depth interviews, capturing of field notes and researcher triangulation. Researcher triangulation occurs when two or more skilled researchers are involved in the analysis of data in an attempt to compensate for single-researcher bias (Curtin & Fossey 2007:91).

Transferability was enhanced by way of a dense description of the demographic data of the participants and a rich description of the results with supporting direct quotations from the participants. Dependability of the study was enhanced through dense description of the research methodology. In addition, the researcher held a consensus discussion with an independent coder, who is very conversant with qualitative data methods. The research process was identified clearly in this study. Confirmability was the last measure considered and evidence for the data process was provided. Literature review of international publications was utilised extensively in order to support the findings of the results. Authenticity of the research was attained by a description of how the advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners view supervision.

Ethical considerations

The ethical standards in this research were based on the three ethical principles of respect for autonomy, beneficence and justice (Dhai & McQuoid-Mason 2011:140). The research was approved by the High Degrees and Academic Ethics Committee of the University of Johannesburg (reference number 36/06). Informed consent was obtained from the participants after an explanation about the research purpose and methods was given to them, along with an explanation regarding their right of voluntary participation and right to withdraw at any stage of the research. The obligation to respect anonymity and confidentiality was applied to the interviewers and independent coders. For the purpose of the principle of beneficence, the participants were informed about the benefits of the research study: that they would be contributing to advanced psychiatric nursing practice and supervision. The principle of justice connotes fairness and equity (Dhai & McQuoid-Mason 2011:15; Polit & Beck 2012:155). The participants were all given an equal opportunity to take part in the study. Criteria for inclusion guided the eligibility of participants to take part in the study in order to share their ideas and needs regarding supervision.

Discussion

Eight advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners participated in this research. All of the participants had been in private practice for more than two years, were English-speaking, of middle socio-economic status and between the ages of 40 and 60 years. Two of the practitioners had PhD qualifications in psychiatric nursing and a Master Coach qualification, three had a PhD in psychiatric nursing and three had a master's qualification in psychiatric nursing.

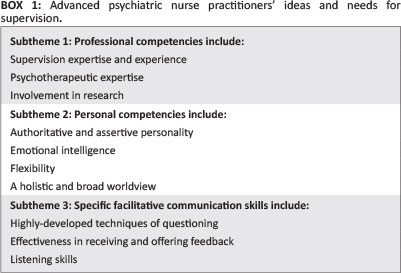

The participants identified one central storyline: that a supervisor should possess certain competencies for supervision. The central theme indicates that a competent supervisor is needed for the supervision of an advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners. The competence of the supervisor is demonstrated by professional competencies, personal competencies and specific facilitative communication skills. This central storyline was clustered into three themes, as is shown in Box 1.

Subtheme 1: Professional competencies

From the findings it can be shown that the participants highlighted the need for a supervisor who possessed professional competencies such as supervision experience and expertise, psychotherapeutic experience and active involvement in research activities. Epstein and Hundert (2002:226) refer to professional competence as the habitual and judicious use of communication, knowledge, technical skills, clinical reasoning, emotions, values, and reflections in daily practice for the benefit of both the individual and the community being served. Binnie (2011:585) suggests that competence should be considered an important factor in supervision, as it is a measure thereof and can also highlight areas for development.

Supervision expertise and experience

The participants indicated that a supervisor needs to be knowledgeable and have vast experience in supervision. They indicated that they need a supervisor who has 'been there' before. This means that a supervisor must have gone through the process of being supervised. The participants stated:

'It would be if I looked at the person, it would definitely be someone that they themselves have gone through supervision'. (P1, Female, 55)

'I think the person that is doing the supervision has to be on a master level'. (P3, Female, 50)

'I would want to be supervised by a person that they, themselves are being supervised'. (P2, Female, 50)

In a study conducted by Sloan (2006:136) on the characteristics of a good supervisor, participants indicated that they relied on their previous experiences of receiving supervision in order to guide the supervision process with supervisees. Alexander and Renshaw (2005:47) indicate that a supervisor must have the experience and capabilities to ensure that there is value in every supervision interaction and to enable people to go beyond what they thought was possible.

Watkins (2012:47) argues that a supervisor's experience and expertise is considerably important, as it affects all aspects of supervisee learning, as well as personal and professional growth. A competent supervisor must have education, training and the experience necessary to be competent in the areas of expertise in which they are providing supervision (Gold, Samios & Lockwood 2000:119; Haynes, Corey & Moulton 2003:159; Kilminster et al. 2007:4).

Psychotherapeutic expertise

Psychotherapy is grounded in the counselling and psychology professions. However, advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners are also trained in psychotherapy during their educational preparation at an advanced level. In contrast to advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners, psychologists and counselling psychologists are expected by the Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA) to both receive and give supervision. In psychiatric nursing, however, there is a paucity of empirical knowledge concerning supervision in the field.

The advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners (APNPs) indicated a preference for a supervisor who has psychotherapeutic expertise. They stated the following:

'A supervisor should have [a] background in either psychology or psychiatry'. (P4, Female, 55)

'Supervisor should have [a] background in either psychology, psychiatric nursing'. (P2, Female, 50)

'... a supervisor also needs to have extensive knowledge in terms of behaviour modification'. (P3, Female, 50)

From the comments above, it is evident that a supervisor should have a clear understanding of and be knowledgeable about the theoretical models utilised in supervision. A supervisor also needs to have a sound theoretical basis on which his or her knowledge of clinical practice rests (Gold et al. 2000:119; Haynes et al. 2003:130).

The number of trained supervisors with psychotherapeutic experience in psychiatric nursing is limited. McKenna et al. (2010:269) suggest that it is possible that the APNPs could be supervised by colleagues from disciplines other than psychiatric nursing. The debate continues in health professions circles about what the exact role is of APNPs when conducting psychotherapy.

Involvement in research

The APNPs expressed a need for a supervisor who keeps abreast of new developments and who is engaged in research activities. The following statements illustrate the need for a supervisor to be involved in research:

'A supervisor must be well read and also well researched'. (P4, Female, 55)

'A supervisor should be very involved in research and also in our context ...'. (P2, Female, 50)

Research is viewed as being an integral component in the practice of any profession. An involvement in research activities will indicate a commitment to the advancement of the psychiatric nursing profession. Supervisors must be involved in research in order to hone their skills in relation to various researched approaches to supervision. This means that the supervisor should remain widely read and actively seek details of advances in the supervision field, which will inevitably bring with it a raised awareness of both supervisor and supervisees (Clutterbuck & Lane 2004:198).

According to Haynes et al. (2003:159), a competent supervisor periodically updates his or her knowledge and skills on supervision through research, workshops, conferences and vast reading.

Subtheme 2: Personal competencies

The personal competencies identified by the APNPs in private practice included being an authoritative and assertive person, as well as having emotional intelligence, flexibility and a holistic and broad worldview.

An authoritative and assertive personality

The APNPs indicated that a supervisor should be authoritative and assertive. An authoritative and assertive personality denotes a person who is direct - standing firm and saying what she or he means in communicating with others.

One of the advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners noted:

'An assertive kind of person, who speaks with authority, a connector ... I think a high[ly] emotional intelligent person'. (P1, Female, 50)

Another commented:

'I want a person who is credible and has credible qualifications and experience ... not someone young, someone who is mature ...'.(P2, Female, 50)

Scaife (2001:203) proposes that when supervision is undertaken a discussion of authority and hierarchy, as well as the implications of these factors, needs to take place at the outset. The supervisor and the advanced psychiatric nurse practitioner may come to supervision with preconceived notions of what it means to be an authority and these notions will affect their capacity to handle their relationship. Haynes et al. (2003) refer to authority as the right to influence or control others. The authors argue that the supervisory relationship has a built-in power differential and that the supervisor is the authority in the relationship. An assertive personality denotes a character of person who communicates in an honest, confident manner and who exercises his or her own rights without denying the rights of others.

Emotional intelligence

The APNPs indicated that a supervisor who conducts supervision should be emotionally intelligent. They had the following to say about such a supervisor:

'These persons' emotional intelligence is utmost important [sic]. The supervisors should be emotionally secure, self-aware and authentic ...'.(P5, Female, 55)

'I think in terms of also emotional intelligence that would be very important to me that the person reflects emotional intelligence in terms of self-control, being sensitive of my emotions, being able to identify my emotions correctly, elicit that for me, motivate me, because I believe motivation is ... being able to inspire me'. (P3, Female, 50)

Goleman (1996:46) argues that emotionally intelligent individuals excel in human relationships, show marked leadership skills and perform well in whatever they do. Davys and Beddoe (2010:163) support the view that a person who has emotional intelligence is someone who conveys warmth and respect and elicits those responses from others, communicates clearly and does not play power games, achieves a balance between personal acknowledgement of others and the formal aspects of professional relationships, has broad networks of relationships, is optimistic, examines mistakes for opportunities to learn and looks for solutions with mutual benefits.

Wall (2007:66) suggests that individuals cannot teach something to others that they themselves do not possess. To be a credible supervisor, the supervisor must embody the very competencies that the supervisor is developing in others.

Flexibility

The participants agreed that the supervisor should demonstrate flexibility in the supervision. One of them commented:

'They should be open minded and flexible and be able to tolerate ambiguity'. (P2, Female, 50)

Another added:

'And I think another thing is flexibility. That the supervisor needs to be flexible in his or her approach'. (P3, Female, 50)

Yet another stated:

'I think the supervisors also need to be aware of the fact that when there is training needs, when there is a consistent message coming through that we need to be trained in a particular area, to be able to make that available as an added value'. (P5, Female, 50)

In supervision, flexibility refers to collaboration between the supervisor and the APNPs to define what to work on and how to work together in the supervision process. However, Hawkins and Shohet (2006:50) describe flexibility as being a quality that a supervisor can utilise in order to move between theoretical concepts and for a wide variety of interventions and methods. Similarly, Haynes et al. (2003:159) agree that a competent supervisor must be flexible and able to assume a variety of roles and responsibilities in supervision.

Furthermore, Austin and Hopkins (2004:77) state that without flexibility a supervisor is seriously constrained in today's constantly changing environment.

In addressing this issue, the authors argue that the supervisor must be flexible within the supervision relationship with the supervisees and take guidance from a growing number of new role definitions such as mentoring, coaching and 'shadowing' (Austin & Hopkins 2004:77).

In practice, effective supervisors should move appropriately and skilfully in order to be flexible and adaptable, developing their own unique style, playing to their own strengths and modulating their approach according to the circumstances and needs of the APNPs under their supervision (Austin & Hopkins 2004:77; Hawkins & Shohet 2006:50; Haynes et al. 2003:159).

A holistic and broad worldview

Advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners in private practice expressed the view that the supervisor must have a holistic and broad worldview. This is in order to bring about different perspectives in the supervision.

One of the APNPs stated:

'The supervisor's world view should be congruent with my own'. (P6, Female, 55)

Another APNP agreed, saying:

'I want a relationship with this person where the result is holistic performance for me and my coaches'. (P3, Female, 50)

Yet another APNP added:

'This person must have a broad view of things...'.(P5, Female, 50)

Fitzgerald and Berger (2002:13) suggest that, in order to establish rapport, it is important to understand how others see the world and to discover their goals and what they care about. Furthermore, they suggest that, with time, it is possible to challenge a client's view gently and offer ideas or approaches, but initially it is vital to be on the same wavelength.

Subtheme 3: Specific facilitative communication skills

There was agreement amongst the APNPs that a supervisor should have interpersonal skills in order to facilitate supervision. Facilitative communication skills form an integral part of any helping relationship - it is all about knowing how to listen, talk, ask questions and establish a rapport with people and how to guide and motivate them to perform the desired actions.

Specific facilitative communication skills identified by the advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners included highly-developed questioning techniques; effectiveness in receiving and offering feedback; and listening skills.

Highly-developed questioning techniques

Effective questioning lies at the heart of any helping relationship such as psychiatry, social work and psychology. Dembkowski, Eldridge and Hunter (2006:45) suggest that questioning should be linked intimately to the supervisor's listening abilities so that that he or she listens for what the APNPs are not detailing in their descriptions of their clients' challenges. The APNPs expressed their agreement in the comments below:

'The supervisor must be skilled in terms of questioning so that I am able to identify my own gaps that I have ...'. (P6, Female, 55)

'The supervisor must also be aware of how to facilitate, how to listen, how to integrate, how to question ...'. (P3, Female, 50)

'To also ask questions and develop my own competencies maybe a complete questionnaire so that you can develop as an advanced psychiatric nurse practitioner in private practice'. (P1, Female, 55)

The skilful use of questioning will require the supervisor to be reflective, to think about the phrasing of questions and the intended outcomes of the questions and, most importantly, to notice the effect that the question has on the participant in the process. The development of effective questioning abilities is therefore an iterate process involving practice, experimentation, observation and reflection (Dembkowski et al. 2006:48).

Questions are asked in order to generate responsibility on the part of the person being supervised to decide what action, from possible options, needs to be taken and what is needed to put that action into effect (Smith 2004:102).

Effectiveness in receiving and offering feedback

Feedback is the process of telling another individual how they experience the process. It is a central skill of supervision and carries an expectation that the supervisee will hear, acknowledge, consider and review his or her understanding (Davys & Beddoe 2010:139). The participants commented:

'Personally, for me, in a supervision relationship things would be important like confidentiality, trust, integrity, honesty also in terms of providing feedback'. (P3, Female, 50)

'I think the supervisor should be candid as well and be able to talk to you and give you any feedback of what he says'. (P6, Female, 55)

'This person must be a good communicator, implying the ability to carry over a message adequately, give and receive feedback in a constructive manner'. (P4, Female, 55)

Hawkins and Shohet (2006:83) argue that giving and receiving feedback is fraught with difficulty and anxiety, because negative feedback re-stimulates memories of being rebuked as a child and positive feedback goes against injunctions not to 'have a big head'. Davys and Beddoe (2010:139) are of the opinion that effective feedback needs to be present at all stages of the supervision process. The giving and receiving of feedback both enhances and tests the supervision relationship and is a skill which can be employed by both the supervisor and the supervisee.

Dembkowski et al. (2006:53) suggest that, in supervision, it is the supervisor's responsibility to provide feedback that is purposeful and with positive intent. In addition, the overall aim is to provide relevant feedback at the most effective point in the supervision process.

The literature indicates that feedback is a difficult art that needs to be practised and it can be difficult for supervisors to know when to employ it. However, it is possible for supervisors to give constructive feedback. Smith (2004:114) suggests that supervisors must create a climate that will encourage the supervisees to seek feedback. In addition, the supervisor must be able to provide honest, fair and constructive feedback (Hawkins & Shohet 2006:83; Kilminster et al. 2007:12).

Listening

The participants were of the opinion that listening is crucial for a supervisor during the supervision process. They stated:

'In the supervision process the person should listen attentively and have good skills in terms of communication ...'. (P6, Female, 55)

'The supervisor must also be aware of how to facilitate, how to listen...'. (P4, Female, 55)

'Sometimes it's not so much about getting ... the outcome it can be just to get someone that listens to you reflects back, ask you thought-provoking, reflective questions'. (P2, Female, 50)

In the study by Sloan (2006:29), participants indicated that having good listening skills is one of the important competencies that a supervisor should possess. Haynes et al. (2003) agree that a competent supervisor must have effective interpersonal skills and be able to work with a variety of groups and individuals in supervision. Stickley and Freshwater (2006:18) point out that listening is an art; it is more than a biological function between the ears and brain.

Dembkowski et al. (2006:40) argue that listening, in any context, requires one to concentrate on what the client is saying, how the client is saying it and what he or she is not saying. In addition, Smith (2004:80) suggests that effective listening involves hearing what is being said, understanding the message and its significance and communicating the understanding back to the audience. He further comments that good rapport, effective long-term relationships and working well together all depend on effective listening.

Limitations of the study

There were no real limitations to the study. However, there was a constraint experienced in the scheduling of the interviews with the participants because of their demanding work schedules, meaning that some of the interviews had to be rescheduled.

Recommendations

From the findings of the study, the following recommendations were made in relation to nursing practice, nursing research and nursing education.

Nursing practice

Supervision should be implemented in mental health settings and private practice as best practice in order for psychiatric nurse practitioners to reflect on their daily challenges in nursing practice. This can be beneficial with regard to assisting psychiatric nurse practitioners to improve their nursing practice. Clouder and Sellars (2004:262) concluded, in their study conducted on reflective practice and clinical supervision, that supervision can be advantageous to individual practitioners and professional groups with regard to enhancing practice and accountability and promoting professional development.

Continued professional development for advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners should be implemented so as to equip them as supervisors for psychiatric nurse practitioners. Cleary et al. (2011:3562) point out that continued professional development is part of professional responsibility and accountability and is essential to professional success.

Advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners can act as supervisors or facilitators to assist nurses to reflect on their daily challenges in nursing practice.

In-service training workshops can be conducted in order to improve the art of communication and the professional and personal competencies for psychiatric nurse practitioners.

Nursing research

The possibility for future research focusing on supervision and psychiatric nurse practitioners is vast. Research can be conducted in mental health settings with psychiatric nurse practitioners so as to explore their ideas about and needs for supervision. Cleary and Freeman (2006:995) point out that psychiatric nurse practitioners can benefit from supportive strategies such as supervision in order to encourage professional practice.

Nursing education

Nurse practitioners can be trained as supervisors from a cohort of advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners to facilitate supervision in mental health settings. The advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners are prepared in postgraduate education and possess therapeutic skills in conducting psychotherapy. It is suggested that the content of training should include education on supervision models in nursing, supervision relationship and the supervision process.

Conclusions

It is evident from the study that there is a need for a supervisor who possesses professional and personal competencies as well as facilitative communication skills. A culture of support needs to be fostered in mental health settings for psychiatric nurse practitioners and advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners in order to enhance professional practice. Advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners cannot continue to work in isolation in private practice. They will benefit from ongoing feedback that will assist them in their professional and personal development. Wheeler (2007:3) indicates that advanced psychiatric nurse practitioners should receive supervision in order to gain proficiency and to deepen their knowledge in modalities of psychotherapy.

Acknowledgements

My thanks go to the University of Johannesburg for financially supporting this project, to Mrs L. Romero for her assistance with the technical editing of the manuscript and to Dr Y. Havenga for the independent coding of the data.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationship(s) which may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

M.A.T. (University of Johannesburg) prepared and wrote the manuscript. M.P. (University of Johannesburg) and C.P.H.M. (University of Johannesburg) were the supervisors of the study and assisted with the final draft of the manuscript.

References

Alexander, G. & Renshaw, B., 2005, Supercoaching: the missing ingredient for high performance, Random House, London. [ Links ]

Austin, M.J. & Hopkins, K.M., (eds.), 2004, Supervision as collaboration in the human services: building a learning culture, Sage Publications Inc., New York. [ Links ]

Bedward, J. & Daniels, H.R.J., 2005, 'Collaborative solutions - clinical supervision and teacher support teams: reducing professional isolation through effective peer support', Learning in Health and Social Care, 4(2), 53-66. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1473-6861.2005.00090.x [ Links ]

Binnie, J., 2011, 'Structured reflection on the clinical supervision of supervisees with and without a core mental health professional background', Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 32(9), 584-588. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2011.576325 [ Links ]

Broom, C., Shirk, M.J., Pehrson, M.S. & Peterson, K., 2008, 'Perspectives on psychiatric consultation liaison nursing: psychiatric-mental health-advanced practice nurses: transforming nursing practice', Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 44(2), 131-134. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6163.2008.00163.x [ Links ]

Canadian Nurses Association, 2008, Advanced nursing practice: a national framework, viewed 30 December 2013, from http://www2.cna-aiic.ca/CNA/documents/pdf/ publications/ANP_National_Framework_e.pdf [ Links ]

Christensen, M., 2011, 'Advancing nursing practices: redefining the theoretical and practical integration of knowledge', Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20(5-6), 873-881. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03392.x [ Links ]

Cleary, M. & Freeman, A., 2006, 'Fostering a culture of support in mental health settings: alternatives to traditional models of clinical supervision', Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 27(9), 985-1000. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01612840600899907 [ Links ]

Cleary, M., Horsfall, J., O'Hara-Aarons, M., Jackson, D. & Hunt, G.E., 2011, 'The views of mental health nurses on continuing professional development', Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20(23-24), 3561-3566. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03745.x [ Links ]

Clouder, L. & Sellars, J., 2004, 'Reflective practice and clinical supervision: an interprofessional perspective', Journal of Advanced Nursing, 46(3), 262-269. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.02986.x [ Links ]

Clutterbuck, D. & Lane, G. (eds.), 2004, The situational mentor, London, Gower Publishing Ltd. [ Links ]

Creswell, J.W., 2007, Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches, 2nd edn., London, Sage Publications, Inc. [ Links ]

Creswell, J.W., 2013, Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches, 3rd edn., Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage Publications, Inc. [ Links ]

Curtin, M. & Fossey, E., 2007, 'Appraising the trustworthiness of qualitative studies: guidelines for occupational therapists', Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 54(2), 88-94. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1630.2007.00661.x [ Links ]

Davys, A. & Beddoe, L., 2010, Best practice in professional supervision: a guide for the helping professions, Philadelphia, Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [ Links ]

De Vos, A.S., Strydom, H., Fouché, C.B. & Delport, C.S.L., 2011, Research at grass roots: for the social sciences and human services professions, 4th edn., Pretoria, Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

Dembkowski, S., Eldridge, F., & Hunter, I., 2006, The seven steps of effective executive coaching, London, Thorogood. [ Links ]

Dhai, A & McQuoid-Mason, D., 2011, Bioethics, Human Rights and Health Law: Principles and Practice, Cape Town, Juta Legal and Academic Publishers. [ Links ]

Epstein, R.M. & Hundert, E.M., 2002, 'Defining and assessing professional competence', Journal of the American Medical Association, 287(2), 226-235. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.287.2.226 [ Links ]

Fitzgerald, C. & Berger, J.G. (eds.), 2002, Exclusive coaching: practices and perspectives, Palo Alto, CA, Davies-Black Publishing. [ Links ]

Fulcher, C.D., 2011, 'Roles of psychiatric and mental health APNs', ONS Connect, 26(6), 17. [ Links ]

Gold, J.H., Samios, K. & Lockwood, J., 2000, 'The question of psychotherapy supervision', Australasian Psychiatry, 8(2), 116-120. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1665.2000.00258.x [ Links ]

Goleman, D., 1996, Emotional intelligence, London, Bloomsbury Publishing. [ Links ]

Hamric, A.B., Spross, J.A. & Hanson, C.M., 2009, Advanced practice nursing: an integrative approach, 4th edn., St Louis, MI, Saunders Elsevier. [ Links ].

Hawkins, P. & Shohet, R., 2006, Supervision in the helping professions. 3rd edn., Berkshire, McGraw-Hall Education, Open University Press. [ Links ]

Haynes, R., Corey, G. & Moulton, P., 2003, Clinical supervision in the helping professions: a practical guide, Pacific Grove, CA, Brooks Cole. [ Links ]

Hines-Martin, V. & Robinson, K., 2006, 'Supervision as professional development for psychiatric mental health nurses', Clinical Nurse Specialist, 20(6), 293-297. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00002800-200611000-00010 [ Links ]

Kilcullen, N., 2007, 'An analysis of the experiences of clinical supervision on registered nurses undertaking MSc/graduate diploma in renal and urological nursing and on their clinical supervisors', Journal of Clinical Nursing, 16(6), 1029-1038. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.01661.x [ Links ]

Kilminster, S., Cottrell, D., Grant, J. & Jolly, B., 2007, 'AMEE guide No. 27: effective educational and clinical supervision', Medical Teacher, 29(1), 2-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01421590701210907 [ Links ]

Kneisl, C.R., Wilson, H.S. & Trigoboff, E., 2004, Contemporary psychiatric-mental health nursing, Upper Saddle River, NJ, Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Kucera, K., Higgins, I. & McMillan, M., 2007, 'Advanced nursing practice: a futures model derived from narrative analysis of nurses' stories', Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 27(4), 43-53. [ Links ]

Lakeman, R., 2000, 'Advanced nursing practice: experience, education and something else' [commentary], Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 7(1), 89-94. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2850.2000.00257.x [ Links ]

LoBiondo-Wood, G. & Haber, J., 2009, Nursing research: methods and critical appraisal for evidence-based practice, 7th edn., St Louis, MI, Mosby Elsevier. [ Links ]

McKenna, B., Thom, K., Howard, F. & Williams, V., 2010, 'In search of a national approach to professional supervision for mental health and addiction nurses: the New Zealand experience', Contemporary Nurse, 34(2), 267-276. http://dx.doi.org/10.5172/conu.2010.34.2.267 [ Links ]

Polit, D.F. & Beck, C.T., 2012, Nursing research: generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice, 9th edn., Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [ Links ]

Pulcini, J., Jelic, M., Gul, R. & Loke, A.Y., 2010, 'An international survey on advanced practice nursing education, practice, and regulation', Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 42(1), 31-39. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2009.01322.x [ Links ]

Rubin, H.J. & Rubin, I.S., 2012, Qualitative interviewing: the art of hearing data, 3rd edn., Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage Publications, Inc. [ Links ]

Savic-Jabrow, P.C., 2010, 'Where do counsellors in private practice receive their support? A pilot study', Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 10(3), 229-232. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14733140903469889 [ Links ]

Scaife, J., 2001, Supervision in the mental health professions: a practitioner's guide, Philadelphia, Taylor & Francis Group. http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780203360941 [ Links ]

Schober, M. & Affara, F., 2006, International Council of Nurses: advanced nursing practice, Oxford, UK, Blackwell Publishing Ltd. [ Links ]

Sheer, B. & Wong, F.K., 2008, 'The development of advanced nursing practice globally', Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 40(3), 204-211. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2008.00242.x [ Links ]

Shenton, A.K., 2004, 'Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects', Education for Information, 22, 63-75. [ Links ]

Sloan, G., 2006, Clinical supervision in mental health nursing, West Sussex, UK, John Wiley & Sons Ltd. [ Links ]

Smith, G., 2004, Leading the professional: how to inspire and motivate professional service teams, London, Kogan Page Ltd. [ Links ]

South African Nursing Council, 1993, Teaching guide for a course in clinical nursing science leading to a registration of an additional qualification, (Based on Regulation R212, Regulations relating to the course in Clinical Nursing Science leading to registration of an additional qualification), Pretoria, SANC. [ Links ]

South African Nursing Council, 2012, Advanced Practice Nursing -SANC's draft position paper/statement, viewed 1 November 2012, from http://www.sanc.co.za/position_advanced_practice_nursing.htm [ Links ]

Stickley, T. & Freshwater, D., 2006, 'The art of listening in the therapeutic relationship', Mental Health Practice, 9(5), 12-18. http://dx.doi.org/10.7748/mhp2006.02.9.5.12.c1899 [ Links ]

TheFreeDictionary, 2013, 'Private practice', viewed 14 February 2013, from http://www. thefreedictionary.com [ Links ]

Wall, B., 2007, 'Being smart only takes you so far: the most successful leaders are masters of emotional intelligence but sometimes they need coaching', Training + Development, January, 64-68. [ Links ]

Watkins, C.E., 2012, 'Development of the psychotherapy supervisor: review of and reflections on 30 years of theory and research', American Journal of Psychotherapy, 66(1), 45-83. [ Links ]

Wheeler, K., 2005, 'The primacy of psychotherapy [Guest editorial]'. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 41(4), 151-152. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6163.2005.00031.x [ Links ]

Wheeler, K., 2007, Psychotherapy for the advanced practice psychiatric nurse, St Louis, MI, Mosby Elsevier. [ Links ]

World Health Organization (WHO), 2001a, Strengthening mental health promotion, Fact Sheet No. 220, viewed 14 February 2013, from http://www.who.int/inf-fs/en/fact220.html [ Links ]

Zorga, S., 2002, 'Supervision: the process of life-long learning in social and educational professions', Journal of Interprofessional Care, 16(3), 265-276. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13561820220146694 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Annie Temane

University of Johannesburg

Doornfontein Campus, 37 Corner Beit and Nind Street

6th Floor East Wing, John

Orr Building, Doornfontein, Johannesburg, 2095

Email: anniet@uj.ac.za

Received: 20 Mar. 2013

Accepted: 23 Nov. 2013

Published: 07 Apr. 2014