Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Curationis

versión On-line ISSN 2223-6279

versión impresa ISSN 0379-8577

Curationis vol.36 no.1 Pretoria ene. 2013

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Lived experiences of a community regarding its involvement in a university community-based education programme

Ntombizodwa S.B. Linda; Ntombifikile G. Mtshali; Charlotte Engelbrecht

Department of Nursing, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Community involvement is one of the crucial principles in the implementation of successful community-based education programmes. However, a gap continues to exist between the rhetoric of this principle and the reality of involving or engaging communities in the education of health professionals.

OBJECTIVES: This study investigated the experiences of a community regarding its involvement in a community-based education programme offered by a university nursing school in Durban, South Africa.

METHODS: An interpretive existentialist-phenomenological design was employed for its richness in extracting human experiences. Individual interviews were held with school teachers and coordinators from non-government organisations, whilst focus groups were used for school children and community health workers. Although focus group discussions are not well suited for phenomenological studies, they can promote active participation and reduce possible intimidation by providing support through group interaction. Analysis of data was guided by Schweitzer's model for analysing phenomenological data.

RESULTS: Themes that emerged from the data include: (1) Community experience of unmet expectations; (2) Benefits to the community from its involvement in the University Nursing School community-based education programme; (3) Existing partnership between the community and the university; (4) Sharing in the case-based learning activities; (5) Awareness of available services, human rights and self-reliance.

CONCLUSION: The researched community indeed benefited in its participation in the University Nursing School (UNS) CBE programme. However, there is a need to improve the communication between partners to make the partnership more sustainable through close relationships and interaction. There is also a need for further research on related aspects of the community's involvement.

Introduction

Community involvement is one of the crucial principles in the implementation of community-based education (CBE) programmes, if they are to achieve what they set out to achieve (Calleson, Seifer & Maurana 2002:79). Community involvement in CBE should be seen as an active process in which the community makes investments in terms of ideas, experience and skills, and takes risks (Williams et al. 1999:730). The role of partners should be to make joint decisions in determining mechanisms for action (Wojtczak 2002:5). The community is commonly viewed as a geographically-designated setting with a specific group of people. In this article, 'the community' refers to a clinical setting that is used as a non-traditional clinical learning site for community-based learning experiences (Carter et al. 2005:168), and it includes both the study participants and non-participants who are sharing resources. This setting offers students an opportunity to learn about socio-economic, political and cultural aspects of health and illness (Mtshali 2005:172, 2009:25).

Problem statement

At the time of conducting the research no studies were found on the subject of inquiry from the community's perspective. Mtshali (2003) indicated a need for more studies to be carried out on the area of community involvement in community-based education (CBE). Although a study was performed by Dana and Gwele (1998), which focused on how the community as a clinical site for learning contributed to student personal and professional development, it did not focus on how the community experienced being involved in the community-based learning (CBL) process. The researcher identified a need to investigate the community experiences of being- involved in the University Nursing School (UNS) CBE as this was a gap in knowledge for the stakeholders. Lack of this information provided an impetus for the researcher to pursue the research. Furthermore, the study was hoped to indirectly evaluate the progress of the UNS CBE programme as this had not been ascertained from the community angle since the implementation of the UNS CBE programme.

Background

The university nursing school reported in this article uses a community-based learning pedagogic strategy which, according to Ibrahim (2010), intentionally integrates service to communities with classroom teaching. This school has been placing students in under-resourced communities since 1994, with community members reported to be actively involved in the learning process. The aim of using communities as experiential learning spaces is to raise the awareness of nursing students about the real health and social issues impacting on the health of people in under-resourced communities, to help them develop professional skills, a sense of civic responsibility, as well as life and academic skills. As stated in Marcus et al. (2011:47), the students in community-based programmes learn by identifying and solving health problems, and working in partnerships with communities. 'Essence of partnership' refers to sharing and joint responsibility (Bernal, Shellman & Reid 2004:33). Authors such as Repper and Breeze (2007:511), however, assert that little is known about how and how much communities are being involved in healthcare education, the effect of their involvement on learning, how successful the different community involvement approaches are, nor how involvement initiatives are being evaluated. This study therefore aimed to establish the nature of the community's experience with regard to partnership with the university and it also indirectly investigated whether expected outcomes of community involvement and partnerships in CBE were attained.

Research methods and design

Design

This study adopted a phenomenological existentialist design, which has the advantage of allowing participants to share their views whilst responding to a 'grand tour' research question (Koivisto, Janhonen & Vaisanen 2002:260; Palmer et al. 2010:99). This design was selected for its ability to collect rich data by taking into consideration the context from which the data are extracted (Darlington & Scott 2002:48-51; Finlay 2009). The philosophical basis for the selected design is the assumption that humans are rational beings, who continually adjust their behaviour to the actions of others. These actions can be adjusted only because they are interpretable (Husserl 1965:23,28,116). The qualitative research approach is grounded in the assumption that individuals cannot be studied outside of the context of their interaction and existence (Burns & Grove 2009; Lincoln & Guba 2005).

Sampling

Purposive sampling was used to identify people, both groups and individuals, from the community who had worked- closely or been engaged with the nursing students during their assignment to the community clinical sites for learning. A sampling frame was compiled by the researcher using the students' previous intervention records which are kept at the UNS. The sampling frame depicted groups and individuals from the community who had participated in the UNS CBE activities during the period 2001-2006.

The selection of schoolchildren, according to specific classes within different school grades, was based on whether or not they participated in any community-based interventions implemented by the university nursing students. However, the children were allowed to willingly and voluntarily accept or reject participation in the study. They were asked by their class teachers to raise their hands to indicate if they wanted to be included in focus group discussions (FGDs). Most children were willing to participate in data collection activities, and it was difficult to either refuse them participation or make them understand that they would be included in the second round of focus group interviews. Some FGDs thus had more than 10 individuals, which is the norm for a manageable group size. To avoid emotional hurt, the researcher allowed them to participate and did the utmost to manage effective group discussions.

The total sample of 57 participants comprised 20 women between the ages of 25 and 45 who are members of the community working as community health care workers; three coordinators of non-governmental organisations (NGOs), not necessarily residing in the community studied; two teachers (one from a junior primary and one from a senior primary school); 30 school children (20 from junior primary schools and 10 from a senior primary school); a manager of a crèche; and a manager of a day care centre.

Data collection method and data analysis

Whilst phenomenological studies often use data collection methods such as participant observation, document analysis and in-depth interviews (Litoselliti 2003:2), this study used individual (Kvale 1996) and focus group (Krueger & Casey 2009 ) interviews. The main research question used in both types of interviews was: 'What is your experience regarding your involvement in the UNS CBE programme'? Four focus group interviews were conducted. Three FGDs were held with schoolchildren, two of which consisted of boys and girls aged between 8 and 11 years from a junior primary school, whilst the third consisted of boys and girls aged between 12 and 17 years from a senior primary school. The fourth focus group comprised community health workers; these were all women aged between approximately 25 and 50 years of age. All FGDs were audio taped with the permission of the participants for cross-checking with interview notes.

Focus groups were used primarily to access data within qualitative parameters that otherwise would not be obtained without group interaction (Palmer et al. 2010:99). Data collection using group interaction was thus deemed necessary- because the subject of inquiry had not been researched before in this community. Taking into consideration that the study included school children, the researcher had to be thoughtful about the best way to obtain data whilst at the same time limiting intimidation and emotional discomfort to participants, especially schoolchildren. The use of focus group interviews was also aimed at providing support to participants through group interaction, as this is believed to strengthen communication, and it can also enhance representativeness through multiple voices (Palmer et al. 2010:100) as opposed to using fewer individuals, as tends to be the case in qualitative studies. Obviously, the use of focus group interviews did not only provide the means for data collection, but also expedited data generation through group interaction. Participants in both focus group and individual Interviewees responded to the same 'grand tour' question; What is your experience regarding your involvement in the UNS CBE programme?' Individual interviews were used for the school teachers, NGO coordinators, and both the crèche and day care managers - a total of six interviews in all. Individual interviews were also audio taped.

Interview guides and probes were used where applicable for both focus group and in-depth inquiries about specific experiences of participants, such as: '[t]ell me more about that'; '[w]hat do you mean by that?'; '[w]hat else can you tell me?'; and '[z']s there anything else that you want to say?'. These allowed participants to expand on the specific experiences they presented.

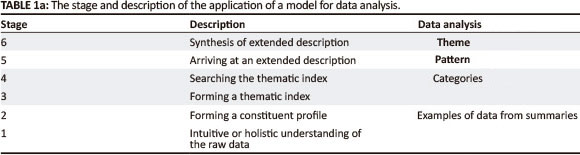

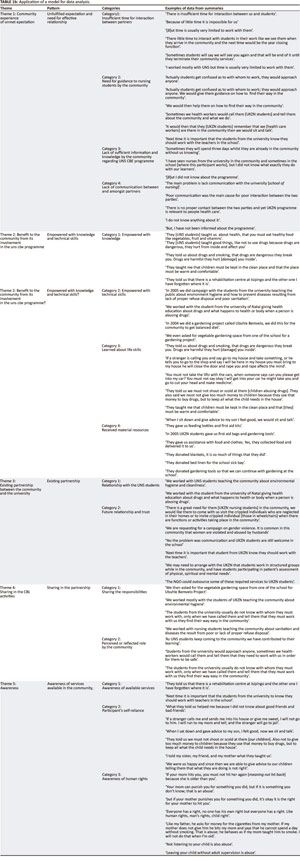

Data analysis was performed by application of the model for analysing phenomenological data designed by Holroyd (2001:3) (as adapted from Schweitzer's 1998 model, and outlined in the Appendix to this article). The model enhanced the explication of the meaning structures developed through the researched experience. During data analysis personal accounts were clearly followed up to establish how these linked to a complex set of group dynamics. The purpose was to take note of personal experiential accounts and to incorporate these with the interactional elements of the group experiences (Palmer et al. 2010:101). Excerpts used in presenting the data are expressions of individual or personal accounts. However, the interpretation of the findings is from the categories which were built from such excerpts and therefore representative of the group. The six steps of the model for analysing phenomenological data enhanced the data analysis process (Sadala & Adorno 2002:289).

Context of the study

The research setting was a rural community located about 7 km from the city centre of Durban in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. The UNS has used this community for more than a decade as a non-traditional CBE clinical learning site for students enrolled in a module in Community Health Nursing. Individuals and groups of individuals from the community who had participated in the selected UNS CBE programme from 2001 to 2006 were targeted for the study. The targeted population includes community health care workers, teachers and children from both junior and senior- primary schools, managers of a local crèche and day care centre, as well as coordinators of NGOs in the community.

Results

Five themes emerged from a rigorous analysis of the categories representing summaries of extracts from participants' responses. Verbatim extracts from participants' responses are used to illustrate the themes.

Theme 1: Community experience of unmet expectations

Categories describing this theme include:

- insufficient time for interaction between partners

- the need for guidance to students by the community

- lack of sufficient information and knowledge by the community regarding the UNS CBE programme

- lack of communication between and amongst partners.

Category 1: Insufficient time for interaction between partners

The feeling is that there is insufficient time for interaction between the partners. This time factor is perceived as being the one most responsible for issues identified as the expectations that were not met. The issue of time was viewed as being the underlying cause for unmet expectations. The statement made by a young adult female participant (aged 30-35), a health worker in the community, indicated as follows: 'There is insufficient time for interaction between us and the only font alternatively remove the interted commas then leave it as part of the pragraphy. Other wise this is suppose to be an excerpt.'

Another middle-aged (40-45 year old) female community health worker reported:

'There is little time to interact with students in their work, like we see them when they arrive in the community and the next time would be the year closing function'.

She further reported the following: 'I worked mostly with UNS students but time is usually very limited to work with them'.

Insufficient time for interaction between partners led to feelings of missed opportunities relating to the partnership. This was also expressed as a lack of sound partnership.

Category 2: Need for guidance to nursing students by the community

Community health workers (CHWs) identified the need to guide nursing students 'when they [the students] are in the community'. The feeling from CHWs that students needed guidance indicates that the CHWs are indeed committed to and willing to share in the education and training of nurses.

This expression was informed by the observation made by health care workers that nursing students usually did not know what their brief or mandate was; that is to say, what they needed to do when arriving at community sites for their learning. In the same vein, health care workers voiced concerns about students not consulting with them- when arriving in the community for learning. The following comments depict these feelings:

'Actually students get confused as to with whom to work; they would approach anyone. We would then give them guidance on how to find their way in the community'. (A middle-aged [40-45 years old] female community health worker)

'It would be then that they [nursing students] remember that we [health care workers'] are there in the community, then we would sit and talk'. (A 30-year-old young adult female, working as a community health worker)

'Next time it is important that the students from the university know they should work with the teachers in the school'. (49 year old female school teacher from junior primary school)

Category 3: Lack of sufficient information and knowledge by the community regarding the programme

A junior primary school teacher indicated that she did not know the details of the CBE programmes although she had seen nursing students at her school. She admitted that she had not bothered much to find out what exactly they do with their [school] learners. This category provides a classical notion of the voice of one teacher participant's experiences as opposed to a collective voice from the community which acknowledged benefits from participation in the UNS CBE programme. This suggests that this particular teacher's class did not participate in the intervention activities that were provided by the nursing students from the UNS:

'I have seen nurses from the university in the community and sometimes in the school [where this participant works], but I did not know what exactly they do with our learners'. (A 49-year-old female school teacher from the junior primary school)

The same school teacher from the junior primary school said, '... but I did not know about the programme', when she recalled that she had indeed seen university nursing students at her school, but had never bothered to find out what they were doing.

Category 4: Lack of communication between and amongst partners

The lack of communication between and amongst partners of the CBE initiative was reported by CHWs. The CHWs experience of a lack of communication emanates from their self-identified and expected role to work with the UNS students when they [the UNS students] are in the community for clinical learning. This was perceived by the CHW participants as posing a challenge at the expense of the ideal partnership:

'Sometimes they will spend three days while they are already in the community without us knowing'. (As explained by a middle-aged [40-45 years old] female community health worker)

'The main problem is lack of communication with the university school of nursing ... but I have not been informed about the programme'. (A 49-year-old female school teacher from the junior primary school)

Another 49-year-old female school teacher from the junior primary school further claimed the following: 'I don't know anything about it'.

Theme 2: Benefit to the community from its involvement in the programme

Different categories describing this theme as verbalised by the participants include being empowered with:

knowledge

technical skills

life skills

material resources.

Category 1: Empowered with knowledge

Varied experiences were described that demonstrate how participants felt they had been empowered by knowledge:

'They taught us about health, that you must eat healthy food like vegetables, fruit and vitamins'. (A junior primary school boy aged 7-10 years)

'They [the UNS students] taught us good things, like not to use drugs because drugs are dangerous, they hurt from inside and affect you'. (A junior primary school girl aged 7-10 years)

Category 2: Empowered with technical skills

CHW participants affirmed that they were also empowered with technical skills, for example gardening, budgeting and life-orientation skills, such as prevention of infection through good hygiene and nutrition. They also reported having benefited mainly from technical skills, whilst school children gained life-orientation skills. To a certain extent, however, there was an overlap of these because of lived experiences on the part of most participants. Experiences were identified from participants' describing the application of knowledge in response to various life challenges, as seen in two comments below, made by a young female health worker, aged 25-35 years:

'In 2004 we did a gardening project called Ubuhle Bemvelo, we did this for the community to get a balanced diet'.

'In 2005 we did a campaign with the students from the university teaching the public about environment hygiene and how to prevent diseases resulting from lack of proper refuse disposal and poor sanitation'.

Category 3: Learned about life skills

Schoolchildren participants acknowledged that they learned about life skills. Learned life skills include avoiding bad practices such as drug use, and interaction with strangers. On the other hand, they learned about good practices, including the benefits of choosing good friends, as well as maintenance of good nutrition and hygiene. Schoolchildren were taught about food hygiene: to cover leftover food so that flies do not contaminate it; and to wash hands before and after meals, especially if they have been digging in soil. Schoolchildren were also clued up about issues relating to human trafficking. They were taught that they should not get into anybody's car unless they know the person or he or she is a family member, and to be watchful of persons who call them either to the car or to their rooms or houses. They said they would run away and go tell their parents:

'They told us about drugs and smoking, that drugs are dangerous, they break you. Drugs are harmful, they hurt (damage) you inside ... They taught me that children must be kept in the clean place and that the place must be warm and comfortable'. (A junior primary school boy aged 7-10 years)

'If a stranger is calling you and say go to my house and take something, or he tells you to go to the shop and say I will be here in my house you must bring to my house he will close the door and rape you and rape affects the mind ... You must not take the lifts with the cars, when someone says can you please get into my car? You must not say okay I will get into your car he might take you and go to cut your head and make medicine ... We learned about HIV that when a girlfriend or a boyfriend is HIV positive and does not use a condom they can infect the other with HIV' (Another school boy aged 7-10 years, from the junior primary)

Category 4: Received material resources

Whilst schoolchildren participants reported that they had learned about life skills, CHWs, on the other hand, reported about having gained material resources. However, the CHWs did not only benefit through tangible commodities; they also acknowledged benefits such as received information, knowledge or skills. CHWs mentioned thing such as gardening tools that were donated by the UNS students. The day care centre manager mentioned receiving resources such as baby-feeding bottles, blankets, first-aid kits, bed linen for the school sick bay and gardening tools. The range of material resources received represented a benefit to the whole community. Of particular note is that all categories of participants mentioned the benefit of material resources; even those who claimed not to know exactly what was being done by the university nursing students mentioned it. Some of the comments by participants were:

'They gave us feeding bottles and first-aid kits and they also donated blankets ... Bandages they gave were very useful as children get hurt easily when they play' (A crèche manager aged 45-50 years)

'They gave assistance with food and clothes. Yes, they collected food and delivered it to us'. (Another crèche manager, verbalising his appreciation)

'They donated gardening tools so that we can continue with gardening at the school'. (A middle-aged [4045 years old] female community health worker)

Theme 3: Existing partnership between the community and the university

The participants indicated that they had gained knowledge through health education on various topics and through interaction with the university nursing students. Both CHWs and schoolchildren shared experiences about managing various issues. Most participants recounted an experience regarding their relationship with the UNS students, and also spoke about their participation with the UNS.

Category 1: Relationship with the students

This relationship was verbalised in many different forms, including acknowledgements of benefits from the partnership as well as unmet expectations. The existing relationship- was construed from the participants' connotation when discussing their activities relating to the partnership. These are some of the participants' comments:

'We worked with UNS students teaching the community about environmental hygiene and cleanliness'. (A middle-aged [40-45 years old] female community health worker)

'We worked with the student from the University of Natal giving health education about drugs and what happens [remove the name of the University] to health or body when a person is abusing drugs'. (A 25-35 year old young adult female working as a health worker)

'Next time it is important that student from UNS to know that they should work with the teachers'. (A 49-year-old female school teacher from the junior primary school)

Category 2: Future relationship and trust

There is a thin line between what could be conceptualised as relating to the nature of the relationship of the community with the nursing students and participation in the CBE activities. However, the debate about such differences is not given any attention in this paper. On the whole, these terms can be used interchangeably where possible. The rationale for this is from the understanding that there is no relationship without partnership and vice versa. Based on the existing partnership participants clearly indicated a need for continuation of the relationship. This is what two of the CHWs had to say:

'There is a great need for them [university nursing students] in the community; we would like them to come with us to visit the crippled individuals who are neglected in their homes'. (A 25-35 year old young adult female working as a health worker)

'Yes the problem was communication and UNS students are still welcome in the school'. (A middle-aged [40-45 years old] female community health worker)

Theme 4: Sharing of the partnership and the responsibilities of community-based learning

Participants from the community studied indicated that they preferred to share in the responsibilities of CBL. This was indicated through a number of activities the community had engaged in, including their positive interaction with UNS students. The community health workers' 'self-propelled' gardening project showed proactive involvement in the execution of the gardening project, which they continued in the absence of the nursing students.

Category 1: Sharing of the community-based learning responsibilities

Participants acknowledged their participation in the nursing interventions of the CBL activities. CHW participants demonstrated a willingness to participate in current and future CBL activities. Sharing of these activities further supports the notion of empowerment as presented in earlier themes. Some comments from participants were:

'We then asked for the vegetable gardening space from one of the school for Ubuhle Bemvelo Project'. (A middle-aged [40-45 years old] female community health worker)

'We worked mostly with the students from the UNS teaching the community about environmental hygiene'. (A middle-aged [40-45 years old] female community health worker)

'The students from the university usually do not know with whom they must work with, only when we have called them and tell them that they should work with us they find their way easy in the community'. (A middle-aged [40-45 years old] female community health worker)

'We worked with nursing students teaching the community about sanitation and diseases the result from poor or lack of proper refuse disposal'. (A 25-35 year old young adult female working as a health worker)

'[0]nly when we have called them and tell them that they must work with us they find their way easy in the community'. (A middle-aged [40-45 years old] female community health worker)

Category 2: Proactive involvement of community health workers

The potential for a future relationship between the partners was indicated. This was evident from participants' statements acknowledging the need to provide guidance to students; the lack of sufficient information and knowledge on the community's side regarding participation in the CBE programme; as well as a lack of sound communication between the partners. Clearly, the community presents a picture of wanting to have these challenges sorted out so that the partnership could work better. Positive expectations included means to enhance the relationship, for example, the need for a trustworthy partnership. Negative expectations include things that need to change in the perceived roles for both partners, as articulated in the following two comments by a young NGO manager, aged 30-35 years:

'We may need to arrange with the UNS that students to work in structured groups whilst in the community, and have students participating in patient's assessment of physical, spiritual and mental needs. The NGO could outsource some of these required services to UNS students ... There is a great need for them [university nursing students] in the community; we would like them to come with us to visit the crippled individuals who are neglected in their homes'.

Theme 5: Awareness of available services, human rights and self-reliance by the community

Findings revealed that community participants were informed by the nursing students about many issues relating to their lives, including awareness about:

- available services in respect of social and health services

- a sense of self-reliance in moral and ethical aspects relating to their lives

- awareness of human rights.

Category 1: Awareness of available services

CHW participants said that they were made aware of many services available in their community of which they had not previously known, as described in the following three statements by a 40-45 year old female manager of a day care centre:

'They told us that there is a rehabilitation centre at Isipingo where drug addicts can be helped to come out of the drug- addiction problem ... They informed us that we can form support group with other parents who are experiencing similar challenges ... We were so happy and since then we are able to give advice to our children telling them that what they are doing is not right'.

Category 2: Participants' self-reliance

Being self-reliant was expressed by all participants but especially by schoolchildren. Participants were aware of the many things learned through their interaction with the nursing students. Schoolchildren mentioned being informed by the nursing students regarding how to handle certain life challenges they were facing. Some of the extracts informing this theme were sensitive, as these were expressions of real-life experiences:

'If a stranger calls me and sends me into his house or gives me sweet, I will not go to him. I will run to my mom and tell her, and the stranger will go to jail'. (A 7-10 year old girl from the junior primary school)

'What they told us helped me because I did not know about good friends and bad friends'. (A 7-10 year old boy from the junior primary school)

'When I sat down and gave advice to my son, I felt good, now we sit and talk'. (A 40-45 year old female manager of a day care centre)

'They told us we must not shout or scold at them [our children]. Also not to give too much money to children because they use that money to buy drugs, but to keep all what the child needs in the house'. (A 40-45 year old female manager of a day care centre)

Category 3: Awareness of human rights

Schoolchildren participants affirmed that they learned many things, such as how to stop or avoid the influence of peers and gangsters, which were the most negative pressures facing them. Peer pressure was experienced as potentially having the effect of losing a friendship, should one fail to comply. Participants showed awareness and the self-reliance to stand by their own decisions. After receiving education on good and bad friendships, schoolchildren affirmed that they would rather lose certain friends than fall into juvenile delinquency. They also learned about their own personal rights. They gained confidence to face their challenges because they understood that they could find other friends, meaning 'good' friends:

'If my friends tell me to do drugs I will not do it, I will rather break the friendship'. (An 11-14 year old girl from a senior primary school)

'I did not know about good and bad friends and that drugs can kill. I will not let my friend get me lost'. (An 11-14 year old girl from a senior primary school)

Ethical considerations

The basic ethical principles that underlie the conduct of biomedical and behavioural research were observed. Permission was sought from the university's Human and Social Sciences Research Office. Written consent was obtained- from participants after they were informed about the study and their right to withdraw from the study any time they wished to. Permission slips requesting schoolchildren to participate in this study were sent to the parents to complete as this was normally carried out by the school. Anonymity and confidentiality were ensured by not using the real names of the participants, in order to prevent emotional harm. Focus group participants were briefed on the importance to respect each other's views and to keep the discussion on the intended purpose of the research (Burns & Grove 2009). Special permission for audio recording was obtained from the participants. Field notes and tape recordings are to be kept under lock and key for three years and destroyed by fire after publishing the study findings.

Trustworthiness

Credibility was maintained through:

appropriate selection of the population

purposive sampling (Burns & Grove 2001:376), which allowed the researcher to select individuals believed to possess specific characteristics relating to the study

bracketing (Rose, Beeby & Parker 1995:1124), where the researcher deliberately isolated her thoughts, judgements, preconceptions and subjective feelings and allowed data to be processed without contamination

member checking of findings, where respondents verified the data and the interpretations thereof (Lincoln & Guba 2005).

The triangulation of data sources - schoolchildren, teachers, health workers and coordinators from the NGOs - also enhanced credibility.

Transferability was enhanced by thorough description of the context and the description of participants' responses using segments of reported data as well as some of the respondents' own comments.

Dependability (Babbie & Mouton 2001:417; Burns & Grove 2001:407) was maintained through the use of a sampling frame which allowed utilisation of participants based on their previous involvement with and exposure to similar interventions.

Confirmability was ensured by observing four qualities of existential phenomenology: description, reduction, essence and intentionality (Burns & Grove 2001:407; De Castro 2003:49). Three months after data were collected and analysed the researcher went back to the participants to confirm that the data were represented as they had intended.

Discussion

The findings of the study suggest the existence of a partnership between the UNS and the community. The participants had experiences that portrayed positive notions of participation. Positive outcomes, including benefits to the community, were appreciated and seen as being a strength of the partnership. Community involvement is one of the most crucial principles- of CBE partnerships and, according to Bringle and Hatcher (2002:504), is the cornerstone of successful CBE programmes. There is a very thin line between what could be understood as relating to the nature of the relationship of the community with the nursing students, and participation in the CBE activities. It was deemed logical to report here more on the nature of the relationship, since there would be no relationship without participation.

Participants' reflections on their experiences informed the study about aspects of the CBE programme that needed revision. Findings confirmed that the participants and community were involved in a variety of ways which demonstrated commitment and willingness in the partnership. The study also revealed that the community had certain expectations from the UNS as a partner. According to Marcus et al. (2011:48), it is normal to have expectations in partnerships - what becomes crucial is the ability to fulfil them. Partners can exchange ideas and suggestions as to how best these expectations can be realised, and this can be achieved through regular feedback and meetings.

Mashego and Peltzer (2005:14) assert that people's experiences have the potential to bring into focus problems that can influence their satisfaction with health care provision. Their study demonstrated that listening to the voice of the people is vitally important, which was also demonstrated in this study of the community's experiences of partnership and involvement. In line with this notion, Bringle and Hatcher (2002:506) support the idea that there are aspects of CBE where improvement is possible, especially where communities do not generally receive valued outcomes in exchange for participation in the CBE process. It would be of advantage to both partners to focus on strengthening the relationships in the partnership as well as providing meaningful participation.

The findings confirmed an existing relationship between the community and the UNS; the community experienced involvement and partnership in their engagement with the UNS. Although the level of involvement and partnership differed for the different categories of community participants, the findings revealed positive outcomes and the potential to improve the relationship. The rationale for this difference related to lack of time, information and effective communication between partners, and the extent of engagement with the different groups in the community. This accounts for the negative experiences as expressed by some participants. These dimensions of engagement point to the need to nurture partnership relationships (Calleson et al. 2002:79). For example, 'need for more guidance to students' was a positively-handled unmet expectation of the participants. Some participants' experiences carried a positive focus and included empowerment through knowledge and skills and material resources. Community health workers mostly acquired technical skills and, to a lesser extent, life-orientation skills. Skills acquired by health care workers include gardening skills, the ability to conduct campaigns- and provide health education to community members, as well as keeping the environment clean to prevent pollution (water, air and land).

Crèche managers reported the benefits of knowledge empowerment. They affirmed having learned how to feed small babies, including the need to let the baby burp before putting it down, and the importance of a balanced diet. In contrast, participating schoolchildren demonstrated that they had acquired life skills rather than technical skills; they believed they now possessed relevant knowledge to allow them to deal with common problems facing them every day. For example, they verbalised being able to apply measures to prevent getting infected with HIV, how to avoid abuse by strangers, being able to engage in sound relationships and friendships, as well as having an awareness of the need to prevent unwanted pregnancies. This is in line with McKeown et al. (2012), who asserted that community involvement should transcend tokenistic forms and have clear examples of expressed genuine empowerment of the community.

The findings further revealed a positive relationship between the community and the UNS. Several issues were identified as being significant hindering factors in the partnership. These included insufficient time for interaction, a lack of information regarding the UNS CBE programme, and a lack of proper communication between partners. The positive nature of the relationship was indicated by a willingness to participate in the CBE programme and the sharing of CBL responsibilities. The community's willingness to share and continue with this participation was the most positive outcome in this study. This is in line with the findings of Calleson, Jordan and Seifer (2005:73) that a gap continues to exist between the rhetoric of principles and the reality of involving or engaging communities in the education of health professionals. However, this can be overcome by mutual redress of the existing relationship.

Whilst participants demonstrated their interest in continuing the relationship with the UNS, they also indicated a need for and the challenge of protecting the relationship by both partners in order to preserve the community's trust and willingness for future participation, as also stated in Marcus et al. (2012). This positive expression by the community should be embraced by the UNS as it will also bring numerous benefits to the university (McKeown et al. 2012), including enhancing the quality of their CBE programme. Benefits cited by the participants from involvement in the UNS CBE programme, included self-development, increased self-reliance, awareness of available services and knowledge, which is a lifetime investment.

Limitations of the study

Notwithstanding the fact that the study was conducted by a novice researcher, there were loopholes with regard to the data-collection process, including (1) age factor of the children as participants, (2) time factor for retrieving of data from child participants, (3) methodology issues, and (4) ethical issues:

Age factor: School children who participated were from 7 to 10 years of age (junior primary school) and 11 to 15 years of age (senior primary school). During interaction with the researcher, it became evident that the participants had enough information to share, but it was given in a very fragmented manner. Although information had been well retained by the participants in some cases, they did not portray a rich, well-grounded expression of their experiences of the phenomena under study. According to (Halloway & Todres 2006) descriptions of 'life worlds' depends on full, rich and articulated verbal accounts by people. This was perceived as a limitation which could result in gaps in information if not handled well. This issue was sorted out during validation as participants were asked to confirm what they meant.

■ Suggestion for the future: Researchers should anticipate this shortfall and be vigilant when collecting data from young (child) participants. This may also be prevented by not leaving a long time between interventions and data collection sessions.

Time factor: School children participants, whose life world experiences with the UNS nursing students were based on once-off interventions were further compromised by the fact that most of them [the school participants] were retrieving expression of their experiences from more than 12 months before (Gerrish & Lacey 2006). The time lapse between interventions and data collection could potentially have caused difficulty in their retrieving their memory of the experience.

■ Suggestion for the future: This may also be prevented by not leaving a long gapbetween interventions and data collection sessions.

Methodological issues (1): A sampling framework to depicting potential participants for the study was used. However, the actual sample did not completely match with the sampling frame owing to the fact that certain individuals depicted in the sampling frame were neither located nor available.

■ Suggestion for the future: This may also be prevented by not leaving long times between interventions and data collection sessions in order to ensure that all potential participants can be still allocated.

Methodological issues (2): Another limitation was that school children participants were selected by school teachers according to a prior list for interventions by UNS nursing students. During the process of the selection of school participants for participation, the teachers actually mobilised more than the required number for each focus group. This led to focus groups numbers being more than was planned as these school children refused to be denied the opportunity to participate.

■ Suggestion for the future: The teacher should be informed beforehand that a certain number of participants is required, to avoid accepting all children who wanted to participate in the intervention sessions. This will avoid feelings of disappointment from the children's point of view.

■ Ethical challenges: The researcher was challenged ethically between exercise control to maintain- required numbers of potential participants for focus groups as was planned and avoiding emotional hurt for the children participants. This resulted from the purposive sampling method used where the school teacher called all students who had participated in UNS CBE interventions. Obviously more than the required number of potential participants showed because interventions were done by classes. The excitement of being selected for the study for these school children who were potential participants made it difficult to stop all of them from participation, not even when offering to putthem on hold for second round participation. Denying them participation could be more of a disappointment. This was a limitation because the researcher then had to deal with more participants in certain FGDs.

■ Suggestion for the future: This may be prevented by effective discussions with the school teachers before the data is collected.

Recommendations

Although this study revealed involvement and partnership between the community and the university school of nursing, there are some areas that require strengthening to allow for a more effective community-academic partnership. This study examined one of the three communities that are used as clinical learning sites. Therefore, further research is needed so as to establish how the other two communities feel about their involvement and partnership with the UNS. Another study may explore in-depth the level of involvement of communities in this particular school's CBL programme, as there are different levels of community involvement. The school has been running its CBE programme since 1994. There is therefore a need to establish the impact made by the UNS CBE programmes in the communities as well as sustainability of the partnership, because one of the principles of partnership states that communities should become more self-reliant and self-determined as a result of community-based interventional activities and their involvement as they mature in the partnership.

Conclusion

The findings of this study show that there is room to improve the partnership, since the community partner is willing to continue participation and expressed the need for services from the university nursing students. The study presents specific issues regarding the partnership that are crucial for sustaining CBE programmes, and it provides a basis for future planning on improving the campus-community-partnerships (CCP) in South Africa. This can be used positively by the partners when taking the partnership forward.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements go to UKZN, for allowing me to pursue my academic and scholarly endeavours in the institution and also for paying for this publication. Supervisor Ms Charlotte Engelbrecht and cosupervisor Prof Mtshali, for their- continued support of and contribution to the production of this manuscript. My Colleagues from my current place of employment (University of the Western Cape, School of Nursing) for reviewing my article during our 'publish or perish' (POP) Writers Club: indeed they inspired me to cherish research.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationship(s) which may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this paper.

Authors' contributions

This article is derived from a mini-thesis Masters research study. C.E. (University of KwaZulu-Natal) was the supervisor and N.G.M. (University of KwaZulu-Natal [UKZN]) was a cosupervisor. The study was registered at the University of Kwa-Zulu Natal. N.S.B.L. (University of the Western Cape) is the first author of the article. N.S.B.L. was a Masters Education student at UKZN. She drafted and worked on the document to completion, but not as a finalised article. C.E. and N.G.M., as supervisor and cosupervisor respectively, had participated in the original study and they were therefore invited to be co-authors in this article. C.E. assisted with the methodology section of the study and, as lead supervisor, she was consulted most when writing this article, giving valuable suggestions and guidance in the construction and structure of the article. N.G.M., as an educationist, guided the pedagogic aspect of the study. N.G.M. helped with updating the references of the article, and provided contributions that were both valuable and useful.

References

Babbie, E. & Mouton, J., 2001, The practice of social research, Oxford University Press, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Bernal, H., Shellman, J. & Reid, K., 2004, 'Essential concepts in developing community-university partnerships. Care link: The partners in caring model', Public Health Nursing, 21(1), 32-40. PMid:14692987 [ Links ]

Bringle, R.G. & Hatcher, J.A., 2002, 'Campus-community partnerships: The terms of engagement', Journal of Social Issues, 58(3), 503-516. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1540-4560.00273 [ Links ]

Burns, N. & Grove, S.K., 2001, The practice of nursing research: conduct, critique and utilization, 4th edn., WB Saunders Company, Pennysylvania [ Links ]

Burns, N. & Grove, S.K., 2009, Practice of nursing research appraisal, synthesis and generation of evidence, 6th edn., Saunders, St. Louis. [ Links ]

Calleson, D.C., Jordan, C. & Seifer, S.D., 2005, 'Community-engaged scholarship: Is faculty work in communities a true academic enterprise?', Academic Medicine, 80(4), 317-321, viewed 1 April 2007 from http://depts.washington.edu/ccph/pdf_files/ComEngScholar.pdf, http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200504000-00002 [password protected], PMid:15793012 [ Links ]

Calleson, D.C., Seifer S.D. & Maurana, C., 2002, 'Forces affecting community involvement of AHCs: perspectives of institutional and faculty leaders', Academic Medicine, 77(1), 72-81, viewed 12 January 2011, from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11788329 [ Links ]

Carter, K.F., Fournier, M., Grover, S., Kiehl, E.M. & Sims, K.M., 2005, 'Innovations in community-based nursing education: Transitioning faculty', Journal of Professional Nursing, 21, 167-174, May-June. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2005.04.004, PMid:16021560 [ Links ]

Dana, N. & Gwele, N.S., 1998, 'Perceptions of student nurses of their personal and academic development during placement in the clinical learning environment', Curationis, 21(2), 58-64. [ Links ]

Darlington, Y. & Scott, D., 2002, 'Qualitative research in practice stories from the field', Open University Press, Maidenhead/Philadelphia. ISBN 0335 21147 X [ Links ]

De Castro, A., 2003, 'Introduction to Giorgis existential phenomenological research method', Psicolgia descade el Caribe, 11, 45-56. [ Links ]

Finlay, L., 2009, 'Debating phenomenological research methods', Phenomenology and Practice', 3(1), 6-25. [ Links ]

Halloway, I., & Todres, L., 2006, 'Grounded theory', in K. Gerrish & A. Lacey (eds.), The Research Process in Nursing, pp. 192-207, Blackwell Publishing, Oxford. [ Links ]

Holroyd, C., 2001, 'Phenomenological research method, design and procedure: Being-in-a phenomenological investigation of the phenomenon of being-in-community as experienced by two individuals who have participated in a community building workshop', Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology, 1(1), 1-12. [ Links ]

Husserl, E., 1965, Phenomenology and the crisis of philosophy: Philosophy as rigorous science and philosophy and the crisis of European man, Translated with notes and an introduction by Quentin Laurer, Harper and Row Publishers, New York. [ Links ]

Ibrahim, M., 2010, 'The use of community based learning in educating college students in Midwestern USA', Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2(2), 392-396. http://dx.doi.org/10.10167j.sbspro.2010.03.032 [ Links ]

Koivisto, K., Janhonen, S. & Vaisanen, L., 2002, 'Applying a phenomenological method of analysis derived from Giorgi to a psychiatric nursing study. Methodological issues in nursing research', Journal of Advanced Nursing, 39(3), 258-265. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02272.x, PMid:12121526 [ Links ]

Krueger, R.A. & Casey, M.A., 2009, A practical guide to for applied research, 4th edn., Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA. [ Links ]

Kvale, S., 1996, Interviews: an introduction to qualitative research interviewing, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA. [ Links ]

Lincoln, Y.S. & Guba E.G., 2005, Naturalistic enquiry, Sage, London. [ Links ]

Litoselliti, L., 2003, Using focus groups in research: continuum research methods, Continuum, London/New York. [ Links ]

Marcus, M.T., Taylor, W.C., Hormann, M.D., Walker, T. & Carroll, C., 2011, 'Linking service-learning with community-based participatory research: An interprofessional course for health professional students', Nursing Outlook, 59(1), 47-54. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2010.10.001, PMid:21256362 [ Links ]

Mashego, T.A.B. & Peltzer, K., 2005, 'Community perception of quality of (primary) health care services in a rural area of Limpopo Province, South Africa: a qualitative study', Curationis, 28(2), 13-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/curationis.v28i2.941, PMid:16045107 [ Links ]

McKeown, M., Malihi-Shoja, L., Hogarth, R., Jones, F., Holt, K., Sullivan, P., et al., 2012, 'The value of involvement from the perspective of service users and carers engaged in practitioner education: Not just a cash nexus', Nurse Education Today, 32(2), 178-184. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2011.07.012, PMid:21885170 [ Links ]

Mtshali, N.G., 2003, 'A grounded theory analysis of the meaning of community-based education in basic nursing education in South Africa', unpublished Doctoral thesis, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Howard College Durban Campus, South Africa. [ Links ]

Mtshali, N.G., 2005, 'Conceptualisation of community-based basic nursing education in South Africa: a grounded theory analysis', Curationis, 28(2), 5-12. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/curationis.v28i2.939, PMid:16045106 [ Links ]

Mtshali, N.G., 2009, 'Implementing community-based education in basic nursing education programs in South Africa', Curationis, 32(1), 25-32. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/curationis.v32i1.870, PMid:20225750 [ Links ]

Palmer, M., Larkin, M., de Visser, R. & Fadden, G., 2010, 'Developing an interpretative phenomenological approach to focus group data', Qualitative Research in Psychology, 7(2), 99-121. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14780880802513194 [ Links ]

Repper, J. & Breeze, J., 2007, 'User and carer involvement in the training and education of health professionals: A review of the literature', International Journal of Nursing Studies, 44(3), 511-519. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.05.013, PMid:16842793 [ Links ]

Rose, P., Beeby, J. & Parker, D., 1995, 'Academic rigour in the lived experiences of researchers using phenomenological methods in nursing', Journal of Advanced Nursing, 21(6), 1123-1129. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1995.21061123.x, PMid:7665777 [ Links ]

Sadala, M.L.A. & Adorno, R. de C.F., 2002, 'Phenomenology as a method to investigate the experience lived: a perspective from Husserl and Merleau Ponty's thought', Journal of Advanced Nursing, 37(3), 282-293. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02071.x, PMid:11851799 [ Links ]

Williams, R.L., Reid, S.F., Myeni, C., Pitt, L. & Solarish, G., 1999, 'Practical skills and valued outcomes: the next step in community-based education', Medical Education, 23(10), 730-737. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00398.x [ Links ]

Wojtczak, A., 2002, 'Glossary of Medical Education Terms', viewed 21 October 2011, from http://www.iime.org/glossary.htm [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Ntombizodwa Linda

Private Bag X17

Bellville 7560, South Africa

Email: nlinda@uwc.ac.za

Received: 23 Nov. 2011

Accepted: 28 Jan. 2013

Published: 24 May 2013

APPENDIX