Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Yesterday and Today

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9003

versão impressa ISSN 2223-0386

Y&T no.30 Vanderbijlpark Dez. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2223-0386/2023/n30a7

ARTICLES

The epistemic views of rural history teachers on school history as specialised subject knowledge

Mbusiseni Celimpilo Dube

School of Education, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pinetown, South Africa. Orcid: 0000-0001-9451-0455; dube.mpilo@yahoo.com

ABSTRACT

This study aimed to understand the epistemic views of history teachers on school history as specialised subject of knowledge. This study adopted the qualitative research approach and interpretivism paradigm. I purposively sampled seven professionally qualified history teachers. For data generation, I used card sorting. What emerged was an unquestionable epistemic certainty to which the teachers steadfastly returned. Broadly speaking, to them school history as the specialised subject of knowledge was about past human actions, promoting human rights, critical thinking, and understanding values. In many ways this spoke of a fixed mindset in which the ideas of what school history should be-namely, procedural historical thinking as part of an analytical approach to the subject as found in the CAPS-History document-had limited to no impact. This could be attributed to the fact that the rural teachers who participated in this study had limited opportunities to be exposed to training related to the CAPS-History curriculum. Hence, their knowledge about school history is rooted in their historical, social, political, educational, and economic reality in which historical knowledge, common or general knowledge, political knowledge, generic skills, and character education are key matters.

Keywords: Views; Rural; History teachers; School history; Specialised subject knowledge; Card sorting

Introduction and background

When the image of rurality is conjured up in the mind's eye a binary ofideas tends to appear. Either a glossy magazine style idea of idyllic romanticised living or one of dust, deprivation, inadequate infrastructure, and poor schooling. Both these images are, however, false. While rural areas in South Africa can experience a lack of basic services, inadequate physical infrastructure and transport which suffers from the brutal legacy of apartheid which brought about Bantustans, they are also spaces of originality, creativity, and resilience where real people live (Balfour, Mitchell & Moletsane, 2008). What, however, cannot be denied is that education in the rural areas of South Africa is not what it is supposed to be. Many schools are in a poor state, lacking basic resources such as textbooks and electricity, and learners have to walk long distances to school after completing household chores and other duties. Furthermore, teachers working in a rural context are not always as well supported or qualified as their urban peers. These challenges were laid bare in, amongst others, The ministerial seminar on education for rural people in Africa: policy lessons, options and priorities (Country Report: South Africa, 2005), and the report on education in a rural context for the Nelson Mandela Foundation (2005).

Powerful figures in the rural world as outlined above are teachers. As "rural dwellers", they are generally subjected to the same rural conditions and environment as the learners they teach (Dorfman, Murty, Evans, Ingram & Power, 2004:189). Consequently, they play a powerful role in educating, mentoring, and guiding learners and their communities, and since schools are situated in communities, this implies that the construction and transmission of school history have to consider the needs and an understanding of communities in the broadest sense (Arthur & Phillips, 2000). History educators have an invaluable role in contemporary societies, not only as transmitters of knowledge about the past but also as professionals that can help students develop disciplinary competencies and become aware of their historical consciousness (Seixas, 2017).

This article will specifically focus on history teachers in a rural context and how they view school history: that is recontextualised academic history which, by means of official policy such as the Curriculum Assessment Statement Policy (CAPS)-History and the programmatic curriculum, history textbooks are presented as official history to be taught and learnt (Bertram & Bharath, 2012). More specifically, emphasis will be placed on how the history teachers who participated in this study viewed school history in the Further Education and Training Phase (FET) (Grade 10-12) as specialised subject knowledge. In summary, this article is trying to understand what history teachers, from a deep rural context, understand about history as specialised subject knowledge. At this juncture it is necessary to explain the focus on rural history teachers. Rural teachers in South Africa as a fast urbanising country, fill a certain position in society. The author, having spent a lifetime as learner, student, teacher, and university lecturer, in a rural context finds himself in this niche. This birthed, for both personal and professional reasons, a need to develop a conceptual understanding in order to make a scholarly contribution to the understanding of rural history teachers of school history as specialised subject knowledge: an attempt to do what Westhoff (2012:533) termed "seeing through the eyes of a History teacher". In contrast, the analysis of domain-specific epistemic views can help understand students' and educators' ideas about the nature of knowledge in their own discipline (Buehl, Alexander & Murphy, 2002)-a reason why focusing on history and social sciences can in fact provide a clearer picture of teachers' and students' reasoning and perceptions (Maggioni, Fox & Alexander, 2010).

Literature review

For the purpose of this article I regard views as the ability to see something from a particular vantage point. The researcher, from a vantage point of rurality, will engage with how rural history teachers view and understand school history as specialised subject knowledge. Whatever these views are, they are the result of personal and professional self-reflections which enabled history teachers to construct and reconstruct their views (Moin, Breitkopf & Schwartz, 2011). Specialised subject knowledge in itself is the knowledge that is unique to a particular subject,-in the case of this article, school history. Differently put, what makes subjects different from each other. Bertram (2011) and Bertram and Bharath (2012) use the concept specialised subject knowledge in school history. They submit that substantive knowledge or content knowledge entails what happened when, where, how, and why. This means that specialised subject knowledge answers or addresses the aforementioned questions. In short, this is the subject or content knowledge of school history. On the other hand, procedural knowledge refers to procedural historical thinking concepts that are used to give coherence to the content studied in school history (that is the subject studied at school) such as time, empathy, cause and consequence, change and continuity, using historical evidence, multiple perceptivity, and historical significance (Kukard, 2017). Specialised subject knowledge in school history, for the purpose of this article, is therefore about both substantive and procedural historical knowledge.

It is necessary to point out that other views beyond the nature of school history on specialised subject knowlegde, as outlined above, also exist. The views that relate to how social structures have impacted how people live and should live in their society. These views can, it is argued, prepare history learners to adapt, live, and understand their societies. In line with this, Stearns, Seixas and Wineburg (2000:21) argue that school history "defines who we are in the present, our relations with others, relations in civil society i.e. nation and state, right and wrong, good and bad, and broad parameters for action in the future". In addition, Husbands (1996) suggests that school history could furnish learners with knowledge about the intellectual and cultural traditions and evolution of the society of which they will become members. School history, therefore, can teach learners about their role in society, as well as how to live alongside other members of society. It is for this reason that school history is viewed as a discipline that emphasises the role of human activity within society (Voss & Carretero, 1998).

School history is also viewed as having the potential to educate learners. In this regard Stearns (1993:281) argues that school history is the "only available laboratory for studying complex human and social behaviours" or "the only available source of evidence about time". Furthermore, Stearns (1993:282) asserts that learners need to know and understand "how factors that shaped the past continue to influence the balance of change and continuity around them". The fact of the matter is that some of the factors which influenced the past still exist and can still influence the present. Therefore, knowing how these factors were dealt with in the past is incumbent for learners to learn, through school history, from this. To this effect, Pratt (1974) and Tamisoglou (2010) posit that school history can help learners understand positive and negative elements of the past in order to make optimal or informed decisions in the present. For learners to be able to make informed decisions they must acquire generic skills like analysis, synthesis, evaluation, and historical skills like critical thinking and reasoning skills.

School history can also guide learners to be politically aware. As such, school history can teach learners to be tolerant and understand cultures and their origin. Furthermore, learners could develop an understanding of the history of other countries. Previous research has shown that school history has the ability to enable learners to make a comparison between structures of societies with economic, cultural, and political developments (Murphy, 2007) to understand the world in which they live (Grever, Pelzer & Haydn, 2011). Pendry and Husbands (1998) further argue that school history can help learners to understand how a free and democratic society developed over time.

In summary, the views on school history as specialised subject knowledge show that it can contribute to the development of historical and common knowledge in relation to social, educational, political, and cultural aspects. School history as specialised subject knowledge, therefore, has the potential to develop learners through knowledge acquisition and skills development. Much of this is encapsulated in the FET CAPS-History document which speaks of history as the study of change and development in society over time to understand and evaluate how past human action impacts on the present and influences our future in a disciplinary manner by thinking critically. Additionally, the FET CAPS-History document foregrounds the importance of understanding a range of sources of evidence from the past which should be evaluated by asking questions about reliability, bias, stereotyping, and usefulness to realise that multiple perspectives exist on the past (CAPS-History, 2011:6). The FET CAPS-History document also emphasises that citizenship within a democracy is important to understand and necessary to uphold the values of the South African Constitution, act responsibly in a civic manner, and by "promoting human rights and peace by challenging prejudices involving race, class, gender, ethnicity and xenophobia" to prepare learners for local to global responsibility (CAPS-History, 2011:6).

While I have a good sense of the views of rural learners of school history as a subject (Wassermann, Maposa & Mhlongo, 2018), the same cannot be said of especially rural history teachers in a South African context. In fact, international research seems to favour the relationship between the knowledge and expertise and that history teachers need to know how to teach the subject (Heuer, Resch & Seidenfuß, 2017). The lack of emphasis on understanding how history teachers view their subject in a baseline manner as specialised subject knowledge leaves a niche for this article. An analysis of the way educators view school history can provide valuable insights into conceptions that might influence their teaching practices. In this regard, Stoddard (2010) found that teachers' epistemic views about the use of historical sources do not always automatically transfer to daily practices. In turn Sakki and Pirttilä-Backman (2019) found that those educators with a naïve approach to the debate about objectivity tend to show a predilection for fostering patriotism in the classroom, and those that identified the development of critical thinking and historical consciousness among their aims adhered to a reflective epistemic stance. Complex epistemological stances are not always promoted in the curriculum and are usually relegated in favour of a vision in which history is simply viewed as factual knowledge to be transmitted (Déry, 2017). Despite this, the most recent theoretical frameworks ofhistorical reasoning consider the understanding about how historical knowledge is constructed and about the nature of the discipline as a key element alongside procedural and substantive knowledge (Van Boxtel & Van Drie, 2018).

Research design and methodology

This study was undertaken in the rural area of King Cetshwayo district, in the north of Zululand, KwaZulu-Natal.1 This area is characterised by geographical spaces which are often dominated by farms, forests, coastal zones, and mountains. Most of the areas in this district where schools are situated, continue to face a unique set of challenges. This is due to, amongst other reasons, the geographic location of schools, the diverse backgrounds of learners, socioeconomic and infrastructural challenges, rurality, and diverse learning styles at various schools.

The study adopted purposive sampling which means it allowed a deliberate choice of seven participants based on a set of criteria. The researcher therefore selected participants (Gray, 2009; Somekh & Lewin, 2011; Creswell, 2014) based on the fact that they had to come from the rural areas in and around King Cetshwayo district, are professionally qualified as teachers, are history teachers responsible for grades 10-12, and have a minimum teaching experience of five years. The researcher exercised caution pertaining to the size of the sample to ensure that it was large enough to produce rich, thick data (Cohen et al., 2011; Bertram & Christiansen, 2014). The history teachers selected based on the abovestated criteria were willing to participate in the study and shared characteristics similar to those of the general teacher population of the area (Mason, 2002).

For this study a qualitative research approach was employed to gain an authentic understanding of the views of rural history teachers on history as specialised subject knowledge. This was done because it tends to provide an in-depth and detailed understanding of the phenomenon being studied-namely, how the FET History teachers who participated in this study viewed school history as specialised subject knowledge (Gray, 2013; Creswell, 2014; Barbour, 2014). This approach helped address the purpose of the study and underpinned the methods of generating and analysing data used in the study (Thomas, 2013). Since the study was about people giving meaning to their social world, it was located within an interpretive paradigm. This is the case because as researcher I sought to understand how rural history teachers perceive and make sense of their world-more specifically, how these history teachers viewed school history as specialised subject knowledge. A case study approach was used because it deals with description and examination of a social phenomenon and aided me as researcher in understanding the complex and unique views of history teachers pertaining to school history as specialised subject knowledge.

For data generation purposes, blended card sorting were employed. As a first step the participating history teachers were issued with a pack of blank cards and asked to write down an idea per card on what they had in mind about school history as specialised subject knowledge. Thereafter, they were asked to sort the views they presented in the cards in a rank order from the most to the least important (Saunders & Thornhill, 2011).

Once the first step as outlined was completed the sorted cards were set aside and the teachers were issued with a set of cards with a series of12 statements from the FET CAPS-History document and the scholarly literature of school history as specialised subject knowledge. The participating teachers were asked to sort the second set of cards from the most to the least important in their view.

The third and final step in the quest to understand the views took place when a third card sorting activity took place. During this activity the teachers were given their own handwritten set of cards, as well as the cards with statements taken from the scholarly literature and the CAPS-History document. The participants were asked to use both sets of cards and sort them in an integrated manner from the most to the least important in their view. They were at liberty not to use all cards. The aim of the final step was to bring the personal understanding of school history as specialised subject knowledge into conversation with the policy and scholarly statements so as to develop a deep and nuanced understanding of the epistemic views held by the rural teachers of history as specialised subject.

During the final analysis the cards as sorted during each step were categorised into most important, important, and least important by means of a numerical value allocated. This aided me in understanding how the rural history teachers prioritised ideas that relate to school history as specialised subject knowledge. This, along with the three-step card sorting methodology, enabled me to identify and analyse patterns of meaning to illustrate themes that are important in the description of the phenomenon under study and to write up the findings (Linán & Fayolle, 2015).

Data analysis of the epistemic views of rural history teachers on school history as specialised subject knowlegde

The research design and methodology as outlined above were implemented across three steps. During step 1 the participating rural history teachers had to write down on the blank cards issued, an idea per card, on how they viewed school history as specialised subject knowledge. They then had to sort the views they presented on the cards in a rank order from the most to the least important. From the collective views of the rural history teachers, and based on how they ordered their cards, five clear themes emerged regarding school history as specialised subject knowledge.

The first view was that school history as specialised subject knowledge is geared towards the acquisition and development of historical knowledge in a memory history manner. These views were rooted, according to the teachers, in understanding significant world events, knowledge about family history, importance of chronology, understanding heritage and its preservation, how development in different countries took place, history about 'big men' in leadership positions, and important historical events in South African history.

In the same vein, according to the views of the rural history teachers, school history does not only develop historical knowledge but common knowledge as well. There were five views presented by the rural history teachers that related to common knowledge: school history should promote good citizenship, deal with issues of race, promote social responsibility, instil values, and study international relations.

Besides historical and common knowledge, the views of the rural history teachers as captured during step 1 also revealed that, according to them, school history as specialised subject knowledge should develop and promote political knowledge. More specifically it was pointed out that school history should educate learners especially about the South African constitution.

The fourth theme that emerged from the card sorting activity that took place during step 1 was that the rural history teachers viewed school history as capable of developing learners' characters. More specifically the teachers argued that school history as specialised subject knowledge is about instilling life skills and how to behave ethically in society in learners. They also held the view that the study of history issues could help learners to take considered actions.

The final theme that emerged from the organic matter in which the history teachers could share their views during step 1 was that school history should promote generic and historical skills. These skills were identified as historical thinking, critical or reasoning skills, English language communication, analysis, evaluation, information sharing, and problem-solving skills.

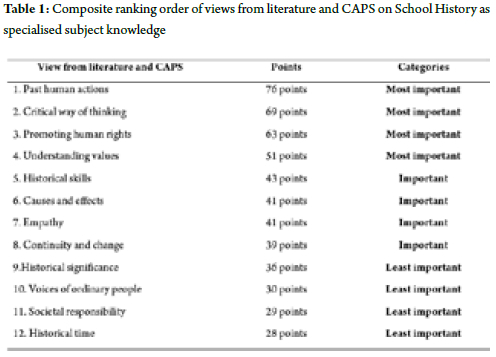

It is against the backdrop of the views of the participating history teachers, which they could express organically on blank cards during step 1, that step 2 of the research methodology took place. During step 2 the participating rural history teachers were given a set of 12 cards containing a series of 12 statements from the FET CAPS-History document (the document that they use to teach grade 10-12 learners) and the scholarly literature on school history as specialised subject knowledge. The participating teachers were asked to sort the second set of cards from the most to the least important. The views of the teachers are captured in Table 1 see below. The ranking were determined as follows: 12 points for a statement they ranked first and 1 point for a statement ranked last or 12th. The views of the teachers were then, based on the scores, ranked as being either most important, important, or least important.

A clear pattern emerged in how the participating rural history teachers engaged with the statement cards as a collective, in that their ranking greatly mirrored their own views as expressed during step 1. What the history teachers regarded as the most important were the more generic aspects of the second set of cards: past human actions, criticial way of thinking, promoting human rights, and understanding values. These views were ranked as the 'most important. This ranking relates directly to the views the teachers held during step 1 on school history as specialised subject knowlegde being about knowing history, thinking critically, promoting the consitituion, and the subject being about incalcating a value system that would birth a prototype citizen. In summary, what they could associate with their own views of school history as specialised subejct knowlegde they ranked the highest.

What followed thereafter (rankings 5-12) were procedural historical thinking skills (also called second order historical thinking skills) as underpinned by the CAPS-History document (the currciulum that they teach) and the 'voices of ordinary people'. The latter can be explained in the sense that during step 1 the teachers made their views clear that the subject is about 'big men. However, the key procedural historical thinking skills (Seixas & Peck, 2004)-numbers ranked 6, 7, 8, 9, and 12-were not viewed as specialised subject knowlegde that is central to school history. What was especially telling is that historical time was ranked last. This is telling since during step 1 the teachers referred strongly to 'chronology and time lines', however, historical time as a concept was probably foreign to them. What was also noticable was that societal responsibility was ranked 11. Clearly, to them as a collective the civic role and virtues they allocated to the subject during step 1 as "civic role" meant something different than societal responsibility.

Having established the views of the participating rural history teachers on school history as a specialsied kwowlegde and how it related to the CAPS-History curriculum and the academic literature, is was necessary to bring their views as expressed during step 1 into conversation with the views expressed during step 2.

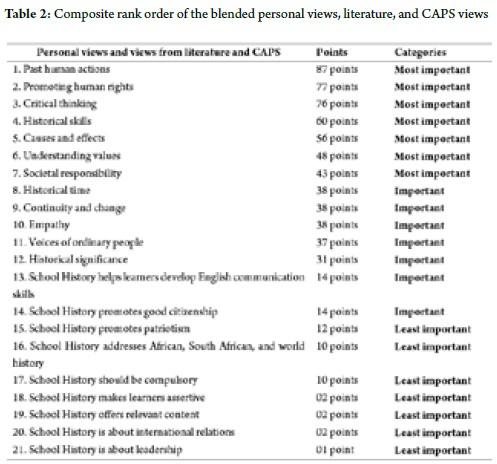

During the final step, step 3, the participating rural history teachers were given their own personal handwritten set of cards created during step 1, as well as the cards with statements based on statements taken from the scholarly literature and the CAPS-History document (step 2). The history teachers were then asked to use both sets of cards and sort them in an integrated manner from the most to the least important. They were under no obligation to use all the cards.

The aim of the final step was to bring the personal understanding of school history as specialised subject knowledge into conversation with the policy and scholarly statements in order to develop a deep and nuanced understanding of the views held by the rural teachers of history as specialised subject. The outcome of, this the final research step, is outlined in Table 3 below. A similar scoring system as the one used during step 2 was applied. The views of the teachers were then, based on the scores, again ranked as either most important, important, or least important.

The card sorting exercise during step 3 revealed a clear continuity in views between steps 1, 2, and 3. The particiapting history teachers ranked past human actions, promoting human rights, critical thinking, understanding values, causes and effects, and historical skills again very highly, meaning they regarded these views as "most important" when it came to specialised subject knowledge and school history. In other words, a clear permanency existed in terms of their views on the key aspects of what constitutes specialised subject knwoeldge in school history.

At the same time the voices of ordinary people were again not valued highly by particpating rural history teachers. Althought historical time as a key historical thinking concept crept up the list, it ended up with other members of the "big six" historical thinking skills (ranked at 8, 9, 10, and 12) in the 'important' category (Seixas & Peck, 2004). The exception proved to be causes and effects which was ranked 5th and this fell under the 'most important' category. This means that what the CAPS-History curriculum foregrounds as specialised subject knowledge, namely historical thinking skills and school history as discipline, were not seen that way by the participating teachers. To them these views were important, but nothing more than that. Instead, their own views of what was most important as specialised subject knowledge remained, for the most part, constant. However, what was telling was that the rural history teachers ranked their own 'specialised ideas' (numbers 13-21) as least important.

Discussion and conclusion of the epistemic views of rural history teachers on school history as specialised subject knowlegde

By means of the methodology as outlined and applied (steps 1, 2, and 3) the participating rural history teachers were given the opportunity to construct and reconstruct their views (Moin, Breitkopf & Schwartz, 2011). What strongly emerged was that the rural history teachers had a shared particular vantage point of what constitute school history as specialised subject knowledge. Whether these views are peculiar to them based on their rurality will be explored lower down.

Key to the views on history as specialised subject knowledge was that it was about substantive historical knowledge-both official (although no reference was at any stage made to the curriculum) and unofficial historical knowledge. This memory knowledge was both inward looking in a nationalistic manner, while foregrounding the actions of big men. The latter has been laid bare by the numerous authors as an integral part of the history curriculum, not only in South Africa but also across the world (Clay, 1992; Manzo, 2004; Hutchins, 2011; Maylam, 2011; Naidoo, 2014). In relation to the above it is also clear that historical knowledge, according to the views of the teachers, should be about knowing political history and espcially the consitution of South Africa. This is not surprising considering that, as argued by Kallaway (2012), South African history curricula, including the CAPS-History curriculum the participating teachers were working with, were for the most part based on political and constitutional history. At the same time the teachers in all probability wanted to ensure that they are seen as being compliant with the values of the post-apartheid political order (Dean & Siebörger, 1995).

Alongside viewing school history as being about 'knowing' it was to the participating history teachers also about common utilitarian, universal knowledge. In other words, to them the subject had a civic role in teaching learners about how to be good citizens that could function in the world. The views as expressed by the teachers are supported by Davies (2001) and Abbott (2009) who accentuate the view that there is a link between history education and good citizenship. This includes inculcating habits of good behaviour and conduct, developing a sense of social responsibility in learners in preparation for active participation in community and national life. It means history can be a mechanism for achieving a prototype citizenship. However, the participating rural history teachers did not present mechanisms for achieving this. In other words, they did not allude to how school history can promote good citizenship. Additionally, the subject was also about building the character of the learners.

What the history teachers in expressing their views were silent on was historial thinking skills or procedural knowlegde-the so-called big six (Seixas & Peck, 2004). Most of these are foregrounded in the CAPS-History document as extremely important in teaching the subject as a discipline that is analytical in nature. It is uncertain if this could be related the rurality of the teachers, meaning that they did not have the opportunity to be regularly exposed to traning workshops on how to implement the CAPS-History document. However, the teachers did foreground the idea that time and chronology was a key thinking skill. This, however, fluctuated in importance (12th in Step and 8th in step 2) in importance. The conclusion that can be drawn is that the teachers understood that learners needed to understand chronology to help them develop historical understanding (Arthur & Phillips, 2000), however, the rural history teachers did not look at chronology in relation to historical understanding, but merely associated it with historical time and timelines. In summary, for the rural history teachers, chronology was only about knowing the temporal unfolding of South African history as, for the most part, a political and constitutional history dominated by big men. It is therefore clear that procedural historical thinking skills were not the 'most important' part of school history as specialised subject knowledge.

They rather embraced different aspects of school history that is beyond the curriculum that included social, educational, political and cultural knowledge. This is in line with what Stearns, Seixas and Wineburg (2000:21) argued, namely that school history "defines who we are in the present, our relations with others, relations in civil society i.e. nation and state, right and wrong, good and bad, and broad parameters for action in the future". This is the history teachers clung to resolutely across all three research steps. This ties in with previous research that has shown that school history is about economic, cultural, and political developments (Murphy, 2007), which is needed to understand the world in which we live (Grever, Pelzer & Haydn, 2011). Pendry and Husbands (1998) further argue that school history can help to understand how a free and democratic society developed over time, hence the teachers foregrounding constitutional and political history as what should be known.

In this article I tried to do what Westhoff (2012:533) termed "seeing through the eyes of a History teacher". This was done by asking the rural history teachers to reflect on their views of school history as specialised subject knowledge. What emerged was a certain epistemic certainty to which the teachers steadfastly returned to. Broadly speaking to them school history as specialised subject knowledge was about past human actions, promoting human rights, critical thinking, and understanding values. In many ways this spoke of a fixed mindset in which the ideas of what school history should be-namely, of procedural thinking as part of an analytical approach to the subject as found in the CAPS-History document-made limited to no impact. This could partially be attributed to the fact that the rural teachers who partipated in this study had limited opportunities to be exposed to training related to the CAPS-History curriculum. Hence their knowledge and knowing about school history is rooted in their historical, social, political, educational, and economic reality in which historical knowledge, common or general knowledge, political knowledge, generic skills, as well as character education are key.

References

Abbott, M (ed). 2009. History skills: a student's handbook (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Arthur, J & Phillips, R 2000. Issues in history teaching. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Balfour, RJ, Mitchell, C & Moletsane, R 2008. Troubling contexts: toward a generative theory of rurality as education research. Journal of Rural and Community Development, (3)3:100-111. [ Links ]

Barbour, R 2014. Introducing qualitative research: a student's guide (2n ed). Los Angeles: SAGE. [ Links ]

Bertram, C & Christiansen, I 2014. Understanding research: an introduction to reading research. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Bertram, C & Bharath, P 2011. Specialised knowledge and everyday knowledge in old and new Grade 6 History textbooks. Education as Change, 15(1):63-80. [ Links ]

Buehl, MM, Alexander, PA & Murphy, PK 2002. Beliefs about schooled knowledge: domain specific or domain general? Contemporary Educational Psychology, 27(3):415-449. [ Links ]

Clay, BJ 1992. Other times, other places: agency and the big man in Central New Ireland. Man, New Series, 27(4):719-733. [ Links ]

Cohen, L, Manion, L and Morrison, K 2011. Research methods in education. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Creswell, JW 2014. Educational research: planning, conducting and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. United Kingdom: Pearson. [ Links ]

Davies, I (ed). 2011. Debates in history teaching. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Dean, J & Sieborger, R 1995. After apartheid: the outlook for history. Teaching History, 79:32-38. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education 2011a. National curriculum statement grades 4-6 curriculum and assessment policy statement. Home languages. Pretoria: Department of Basic Education. [ Links ]

Dorfman, LT, Murty, SA, Evans, RJ, Ingram, JG & Power, JR 2004. History and identity in the narratives of rural elders. Journal of AgingStudies,18:187-203. [ Links ]

Gray, DE 2009. Doing research in the real world (2nd ed). Los Angeles: SAGE. [ Links ]

Grever, M, Pelzer, B & Haydn, T 2011. High school students' views on history. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 43(2):207-229. [ Links ]

Heuer, C, Resch, M & Seidenfuß, M 2017. What do I have to know to teach history well? Knowledge and expertise in history teaching-a proposal. Yesterday and Today, 18:2741. [ Links ]

Hutchins, RD 2011. Heroes and the renegotiation of national identity in American history textbooks: representations of George Washington and Abraham Lincoln, 1982-2003. Journal of the Associationfor the Study of Ethnicity and Nationalism, 17(3):649-668. [ Links ]

Kallaway, P 2012. History in senior secondary school CAPS 2012 and beyond: a comment. Yesterday & Today, :23-62. [ Links ]

Kukard, JK 2017 The trajectory of the shifts in academic and civic identity of students in South African and English secondary school history national curriculums across two key reform moments. Unpublished Med dissertation. Cape Town: UCT. [ Links ]

Liñán, F & Fayolle, A 2015. A systematic literature review on entrepreneurial intentions: citation, thematic analyses, and research agenda. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11(4):907-933. [ Links ]

Mason, J 2002. Qualitative researching (2nd ed). Los Angeles: SAGE. [ Links ]

Moin, V Breitkopf, A & Schwartz, M 2011. Teachers' views on organisational and pedagogical approaches to early bilingual education: a case study of bilingual kindergartens in Germany and Israel. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27:1008-1018. [ Links ]

Maggioni L, Fox E & Alexander PA 2010. The epistemic dimension of competence in the social sciences. Journal of Social Science Education, 9(4):15-23. [ Links ]

Manzo, KK 2004. Countries torn over baring warts in history texts. Education Week, 24(11):8. [ Links ]

Maylam, P 2011. Enlightened rule: portraits of six exceptional twentieth century premiers. Bern: International Academic Publishers. [ Links ]

Murphy, J 2007. 100 + ideasfor teaching history. London: Continuum. [ Links ]

Naidoo, A 2014. An analysis of the depiction of "big Men" in apartheid and post-apartheid school history textbooks. Unpublished MEd dissertation Durban: University of KwaZulu-Natal. [ Links ]

Pendry, A & Husbands, C 1998. History teachers in the making: professional learning. Buckingham: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Pratt, D 1974. The functions of teaching history. The History Teacher, 7(3):410-425. [ Links ]

Saunders, MNK & Thornhill, A 2011. Researching sensitively without sensitizing: using a card sort in a concurrent mixed methods design to research trust and distrust. International Journal of multiple Research Approaches, 5(3):334-350. [ Links ]

Schwartz, SH 2006. Basic human values: theory, methods and applications. Jerusalem: Hebrew University. [ Links ]

Schwartz, SH 2012. An overview of the Schwartz theory of basic values. Online Reading in Psychology and Culture, 2(1). [ Links ]

Seixas, P & Peck, C 2004. Teaching historical thinking. Challenges and Prospects of Canadian Social Studies, pp. 109-117. [ Links ]

Seixas, P. (2006). Benchmarks of historical thinking: a framework for assessment in Canada. The Center for the Study of Historical Consciousness. Recuperado el, 16. [ Links ]

Seixas P 2017b. Historical consciousness and historical thinking. In M Carretero, S Berger & M Grever (eds). Palgrave handbook of research in historical culture and education. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Somekh, B & Lewin, C 2011. Theory and methods in social research (2nd ed). Los Angeles: SAGE. [ Links ]

Stearns, PN 1993. Encyclopedia of social history. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Stearns, PN, Seixas, P & Wineburg, S (eds). 000). Knowing teaching & learning history: national and international perspective. New York: University Press. [ Links ]

Stoddard JD 2010. The roles of epistemology and ideology in teachers' pedagogy with historical "media." Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 16(1):153-171. [ Links ]

Sakki I & Pirttilä-Backman AM 2019. Aims in teaching history and their epistemic correlates: a study of history teachers in ten countries. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 27(1):65-85. [ Links ]

Tamisoglou, C 2010. Students' ideas about school history: a view from Greece. Procedia: Social and Behavioural Sciences, 2:476-480. [ Links ]

Van Boxtel C & Van Drie J 2018. Historical reasoning: conceptualizations and educational applications. In SA Metzger & LM Harris (eds). The wiley international handbook of history teaching and learning. New York, NY: Wiley-Blackwell. [ Links ]

Voss, JF & Carretero, M (eds). 1998. Learning and reasoning in history. London: Routledge Falmer. [ Links ]

Wassermann, J, Maposa, M & Mhlongo, D 2018. "If I choose history it is likely that I won't be able to leave for the cities to get a job": rural learners and the choosing of history as a subject. Journal of Education (University of KwaZulu-Natal), 73:55-68. [ Links ]

Westhoff, LM 2012. Seeing through the eyes of a history teacher. The History Teacher, 45(2):533-548. [ Links ]

1 This article is based on a PhD done by the author under the supervision of ProfessorJohan Wassermann at the University ofKwaZului-Natal. The ethical clearance number for this study is: Ethics HSS/1026/014D