Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Yesterday and Today

versión On-line ISSN 2309-9003

versión impresa ISSN 2223-0386

Y&T no.30 Vanderbijlpark dic. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2223-0386/2023/n30a3

ARTICLES

Tracing the Substantive Structure of Historical Knowledge in South African School Textbooks

Pranitha Bharath

University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa. Orcid: 0000-0002-6175-7109; pranitha.bharath@up.ac.za

ABSTRACT

This article argues that complex substantive knowledge in South African school history textbooks may challenge learners who struggle with reading and comprehension. While debates continue about the balance of substantive and procedural knowledge, both fundamental elements of history knowledge (Lee, 2004), this study employs a qualitative analysis of the substantive content within a Bernsteinian framework. Seven purposively sampled history textbooks, covering grade 3 to grade 9, across the foundation, intermediate, and senior phases of the South African school curriculum are analysed using Maton's (2013) language descriptions of context and semantics as conceptual tools. Additionally, nominalisation techniques (Coffin, 2006) are used to examine language in the text. Findings indicate significant growth in substantive knowledge manifesting through time, space, context, and semantics.1 Substantive knowledge shifts from a rudimentary and contextualised nature to a more abstract and dense form, including domain-specific conceptual knowledge. Advancing grades produce decontextualised knowledge with heightened semantic density. Increased events under study accompany greater participant diversity. A History student working with these materials would need to be highly proficient in language skills and also capable of processing substantial volumes of abstract content knowledge. Alarming statistics from the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (Department of Basic Education, 2023) reveal that 81% of grade 4 learners struggle with comprehension in any language, ranking South Africa at the bottom of 57 countries. It is likely that learners would encounter difficulties with the substantive knowledge evident in these textbooks.

Keywords: Content analysis; Contextualization; History knowledge; Proficiency; Semantic shifts; Textbooks.

Introduction

The study of history is important to understand the past and the shape of the present, and textbooks form a critical part of its delivery. In South Africa, the right to textbooks is part of the broader right to basic education, as guaranteed by Section 29(1)(a) of the Constitution, Basic Education Rights Handbook (2017:266-272). Section 5A requires the National Minister of Basic Education to prescribe norms and standards for the provision of learning and teaching support material including the obligation to procure and deliver textbooks. Since "school textbooks are the dominant definition of the curriculum in schools" (Crawford, 2003:3), the kind of knowledge presented forms the backbone of the learning content, helping teachers manage and direct their lessons, save time while guiding discussion, homework, assessment, and project work. The school history textbook continues to be a powerful pedagogic and learning tool as "local and international research has shown that the textbook is the most effective tool to ensure consistency, coverage, appropriate pacing and better-quality instruction in a curriculum" (Department of Education, 2000:9).

Wheelahan (2010:11) purports that the nature and structure of knowledge have curricular implications for the way it is classified, sequenced, paced, and evaluated in the curriculum, influencing equitable access. Current research foci are on the balance of substantive and procedural knowledge in the school history curriculum. Dean (2004) cites Schwab's distinction of 'substantive' and 'procedural' history with 'procedural' being the 'know-how', the methodology of historians, which are the procedures for conducting historical investigations; and 'substantive' being the 'know that', statements of fact or concepts of history constructed by historians in their investigations. Bertram (2008) contends that learners have to acquire both to be appropriately inducted into the discipline of history.

Lévesque (2008) claims that 'progression' in historical thinking should be simultaneous within each domain of knowledge and not from one to another, clearing the misconception about it being a movement on a linear scale of reasoning from substantive (lower-order thinking) to procedural knowledge (higher-order thinking). Counsell (2018), however, views a "knowledge-rich" curriculum as one associated with substantive knowledge. Drawing from Willingham (2017), Counsell (2018) maintains that attention should be on the relationship between academic content knowledge and reading, on the vocabulary gap between the advantaged and disadvantaged, and on the role of knowledge in making subsequent learning possible. South African history has been influenced by the progressive British movement, the Schools' Council Project (SCHP,1976) which initiated a skills-based approach to the teaching of history internationally and countered the former chronological and factual emphasis. The change from memory-history to disciplinary-history was based on students' understanding of six procedural benchmarks outlined by Martin (2012) and Seixas (2006) as historical significance, use of primary source evidence, identifying continuity and change, analysis of cause and consequence, taking historical perspectives, and the ability to understand the moral dimension of historical interpretation.

History teachers are expected to advance historical thinking in their classrooms and, in so doing, advance school history as an analytical endeavour (Wassermann & Roberts, 2022:1). This is essentially the evidential methodology of history which requires learners to analyse and evaluate historical sources and evidence to formulate interpretations. Bertram (2009:45) asserts that while curriculum reformers have embraced the procedural dimension of studying history, there is a concern of an overemphasis on procedural knowledge over the substantive. Suggesting that textbooks and teachers place more emphasis on the substantive, Oppong et al. (2022:43) argue for a process where history is constructed. Ramoroka and Engelbrecht (2015) have identified the unbalanced relationship between the two knowledge types as a further challenge for history education in South Africa. They advocate for the methodology of "doing history", using the framework of historical thinking. My understanding is that learners who struggle with reading and interpreting knowledge may pose an impediment to this notion of 'doing history.

After a decade of slow progress, South Africa is back to 2011 levels of achievement (PIRLS, 2023). The current South African educational crisis may be attributed to how knowledge is structured, in any language. The Minister of Education Angie Motshekga ascribed the poor interpretation skills to the effects of eleven African languages2 and COVID-19 (ENCA News, 27 June 2023). Motshekga stated that learners were taught in a language that was not necessarily their home language.3 Some teachers are not fully conversant with the language in which they are required to teach which has implications for the learners they teach. While policies can be reviewed and the drive to incorporate the African languages into teaching and learning exists, history textbooks and international tests are still structured in English.

Counsell (2018:1) maintains that little has been written about how learners gain either of the knowledge types, the character of knowledge, its structure, its status, and its relation to learners and teachers. This area of research aligns with the sociology of knowledge which considers education within a framework of promoting social justice (Rata, 2016; Young, 2008). The present study seeks to analyse and describe the character and pedagogic potential of substantive knowledge content in seven textbooks.

Key research questions

The questions, "What is the nature of substantive knowledge in a range of South African textbooks and how do they support learning?", are central to this inquiry. A crucial aspect to consider is the demarcation between what is presented as a fact within the textbooks and the material that allows for contestation. Textbooks present certain dates and events as definitive with a certain consensus that already exists about factual information, raising questions if the nature of history is contested. It prompts the feasibility of disentangling the substantive content (the what) from the procedural (the how). The researcher finds demarcation techniques to identify the substantive knowledge by conducting a systematic content analysis of the historical events and themes under study in each textbook.

Background and contextualisation

Post-apartheid curricular shifts in South Africa in favour of an outcomes-based curriculum C2005 in 1998 have contributed to the ongoing educational crisis. An initial strong focus on generic skills, lack of specific content knowledge, and the discouragement of a comprehensive textbook, led to its failure and replacement with the Revised National Curriculum statement in 2004. The content was reintroduced with a renewed focus on textbooks and reading. The present National Curriculum Statement (NCS) Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) for Grades R-12 came into existence in 2011 unifying all grades in a curriculum with a clear focus on content, term-wise teaching specifications, and a policy of providing one textbook per learner per subject. These changes were mirrored in history as it was first merged with geography in the learning area of social sciences, losing its former nature. CAPS reinstated them as distinct disciplines, each retaining its substantive content. Consequently, the CAPS social sciences (Department of Basic Education, 2011b & c) cover two distinct documents covering grade 4 to 9 history and geography in the General and Training Band (GET), and another for history as a standalone subject in the Further Education and Training Band (FET), encompassing grades 10 to 12.

The General aims of the South African curriculum

The National Curriculum Statement Grades R-12 (2011) is based on the principles of social transformation, active and critical thinking, high knowledge, and high skills: the minimum standards of knowledge and skills, progression in context, and content from simple to complex. The CAPS document (DoE, 2011c:11) highlights the concepts as historical sources and evidence, a multi-perspective approach, cause and effect, change and continuity, and time and chronology, thus conforming to international trends.

Standardized tests for history do not exist at the international level due to the contextual shaping of history knowledge in different countries. This shaping is influenced by factors such as national identities; values; social, economic, and political factors; and other ideological filters. Recent developments in the field of history education have seen increased focus on fostering patriotism and citizenship. Global transitions in leadership have altered national and international curricula and knowledge content, sometimes to the detriment of the 'other' (cultural and national) people. While this paper does not delve into ideological shifts, it examines the structure and status of historical knowledge in textbooks and its influence on progression through the grades in phases of the South African history curriculum. Moreover, it seeks to uncover the implications for a country that is routinely underachieving. It is not only among the worst in the world but often among the worst in the southern African region and in Africa as a whole (Bloch, 2009:17). It is also found that some well-resourced schools are still dysfunctional twenty-five years after democracy, which has been sufficient time to address historical backlogs and inequalities (Arendse, 2019).

Literature Review

Knowledge in text

According to Kissack (1997:215), "knowledge is inextricable from the medium oflanguage in which it is presented". History knowledge is predominantly presented in English. The educational policy allows for English to be studied as a home language or first additional language. The CAPS social science policy documents refer the teachers to the language policy for guidelines on writing in history. The CAPS home languages document (DoE, 2011a:10) states: "We know from research that children's vocabulary development is heavily dependent on the amount of reading they do." It also advances that well-developed 'reading and viewing' skills are central to successful learning across the curriculum, including social sciences, and that learners are expected to develop proficiency in interpreting a wide range of literary and non-literary texts, including visual texts.

The Durkheimian 'differentiation of knowledge' concept in the social realist program consists of the concepts of context-dependent knowledge that are acquired from experience (Vygotsky, 1962; Popper, 1978) and abstract content-independent knowledge (cited in Rata, 2016:171). Rata uses Young's (2010) notion of "powerful knowledge" to highlight its epistemic and specialised properties in assisting learners in abstract and context-independent ways. Winch (2013) uses the term 'epistemic ascent' to describe knowledge at different levels of abstraction and complexity in and outside of specific contexts (Rata, 2016:172). In the absence of a link between the unknown and the known which builds in a logical order, the textbook or teachers themselves may fail as pedagogues. Textbook authors cannot assume that all learners can process the information in texts successfully. History textbooks are powerful tools that can support effective learning, comprehension, and conceptual development. Therefore, how textbooks present knowledge has implications for how students learn history.

The history textbook as an instrument of learning

Seminal works like that of Loewens (1995) in the United States and Counsel (2018) in the United Kingdom are among the large bank of studies that have brought an increased focus on textbook content. South African history textbooks have been scrutinised for various reasons including racism, sexism, stereotypes, and historical inaccuracies (Auerbach, 1965; Du Preez, 1983; Esterhuyse, 1986; Sieborger, 1992; Bundy, 1993 as cited in Engelbrecht, 2005). Morgan's (2011) South African literature review focused on the politics of the curriculum, the perpetuation of segregationist ideals (Dean et al., 1983), the disappearance of White Afrikaner history from textbooks (Pretorius, 2007; Visser, 2007; van Eeden, 2008), white and black role reversal, including how the Afrikaner Nationalists were replaced by the African Nationalists (Engelbrecht, 2008). Bertram and Bharath's (2011) interrogation of history textbook content found an over-prioritisation of everyday knowledge over procedural knowledge and a lack of a sense of chronology, space, and time. The present study traces these constructs in the substantive knowledge of a different sample of textbooks, identifying what contributes to its complexity and how learners gain from it.

The language in textbooks

According to Short (1994:541), reading passages in history are long and filled with abstract and unfamiliar schema that cannot be easily demonstrated. The textbook is identified by Schleppegrell et al. (2012:72) as the primary source of disciplinary knowledge where the content and language of the text cannot be separated. Consequently, language becomes a challenge to learner progression in history simply because it becomes increasingly complex and abstract as learners pass through grades.

For linguistic analysis, Schleppegrell et al. (2012) use Martin's (1991) and Unsworth's (1999) studies of Australian middle school history textbooks to identify key linguistic features of historical discourse. Among these are nominalisations (transformation into a noun/nominal to reorganise clauses) and ambiguous use of conjunctions and ill-defined phrases which challenge students. It can be argued that the indications of complexity or progression are signaled by the patterns of grammar within and across texts. Nominalisation is a language resource used to understand how some texts present decontextualised language of academic knowledge. It is a process whereby events (normally expressed as verbs) and logical relations (normally expressed as logical connectors) are packaged as nouns. The manner in which authors of textbooks fashion the language of the text and the vocabulary choices they make, create challenges for learner understanding. The use of nominalisation in texts increases language density and abstraction.

There is also an understanding that the academic language of the school and textbooks is different from the informal, interactive language of spontaneous face-to-face interaction. This idea is developed by Cummins' (1984) distinction between two differing language types called BICS (basic interpersonal communication skills) and CALP (cognitive academic language proficiency). BICS refer to the 'surface' skills of listening and speaking (or everyday skills) acquired rapidly by students, while CALP refers to the basis for a child to cope with academic demands from different subjects (increasingly subject-specific, technical, and abstract). Cummins (1984) uses this continuum model to categorise the tasks pupils engage with from cognitively undemanding to cognitively demanding and from context-dependent (strong contextualisation) to context-independent (weak contextualisation).

A context-embedded task is one where students have access to a range of visual and oral cues, and meaning is easily acquired. A context-reduced task pertains to reading a dense text where the language is the only resource. Schleppegrell et al. (2008:176) argue that the language of texts, called academic language, presents information in new ways, using vocabulary, grammar, and text structures that call for advanced proficiency in this complex language. New challenges are presented to students to learn to recognise, read, and adopt when they are writing. Teachers face the challenge of simplifying and decoding dense texts, while students are faced with new difficulties in recognising and reading the material.

Martin (2013:23) views these technicalities and abstractions in subject-specific discourses about high-stakes reading and writing. Within the field of systematic functional linguistics (SFL), he advances concepts of power words, power grammar, and power compositions for teachers to use as tools to build knowledge. Martin (2013) describes the transition from primary to secondary phases as a shift from basic literacy to subject-based learning which is composed of specialised discourse of kinds.

The theoretical framework

Sociologist and educational theorist Basil Bernstein highlighted the role of language in shaping educational disparities through his "code theory" which explores the relationship between social classes, language, and educational achievement. His "restricted code" is associated with the working class or marginalised communities and is context-bound, relying on shared experiences. In contrast, his "elaborated code" is linked to the middle class where learning is more abstract and context-independent. According to Bernstein (1971), these codes have different linguistic styles that have implications for learning and socialisation. He classifies school knowledge as formal and specialised, while everyday knowledge is more personal and localised where the context of the home plays a significant role in developing what the learner knows before they come to school. Bernstein (1999) views everyday knowledge as tacit, context-bound knowledge that can be oral and is relevant across contexts. School knowledge, conversely, is classified by Bernstein (1999) as explicit and hierarchically organised with a systematically principled structure. According to Bernstein (1996), school knowledge (academic) categorised as a vertical discourse, and everyday knowledge categorised as a horizontal discourse, are differently acquired and structured.

Studies have shown that the balance between the two types of knowledge can affect learners in different ways (Williams, 2001, as cited in Ensor & Galant, 2005). Research in various fields of study (Ensor & Galant, 2005; Dowling, 1998; Rose, 1999; Taylor & Vinjevold, 1999) has indicated that learners can be disadvantaged by the fusion of academic and everyday practice (cited in Bharath, 2009:39). It can be argued that this disadvantage arises from an exclusive or heavy reliance on the everyday discourse. Naidoo (2009:5), in a study of 'progression and integration', indicated that some historically disadvantaged schools did not provide learners with the opportunities to learn high-level knowledge and skills, and that the dominance of the integration of school knowledge with everyday knowledge compromised the conceptual progression expected of school knowledge, thus disadvantaging learners. Disciplinary knowledge, therefore, is important for the acquisition of certain concepts. According to Hoadley andJansen (2004), specialised formal schooling knowledge is acquired through specific language and concepts. They argue that when everyday knowledge overwhelms school knowledge there is a danger of learners not developing a systematic understanding of the discipline.

Maton's concepts of decontextualised and contextualised knowledge

Extending Bernstein's insights, Maton (2013) in legitimation code theory (LCT) highlights the significance of cumulative knowledge building by making 'semantic waves' in knowledge. These 'semantic waves' refer to the recurrent movement in 'semantic gravity' (context-dependence) and 'semantic density' (condensation ofmeaning) (Matruglio et al., 2012:38).

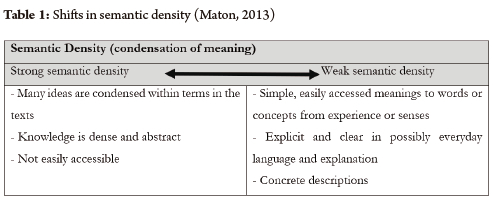

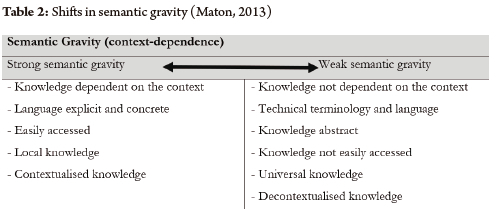

The language of textbooks often displays stronger semantic density in that a lot of ideas are condensed within terms, while at the same time displaying relatively weak semantic gravity in that the knowledge can be out of the learner's context or decontextualised. The knowledge may not necessarily be dependent on a particular context, but can, instead, deal with more abstract principles or generalised phenomena (Matruglio et al., 2012). The teacher 'unpacks' the technical language in the textbooks by providing concrete examples, thereby strengthening the semantic gravity (contextualising the knowledge). Providing simpler explanations in everyday language further elicits meaning, and so weakens semantic density. Producing these shifts up and down semantic scales involves abstracting and generalising away from particular contexts to condensed, larger ranges of meaning into terms and concepts. The following tables summarise these ideas, clearly describing the movement of knowledge in both ways. Table 1 shows the shifts in semantic density and Table 2 shows the shifts in semantic gravity. I use Maton's concepts as a language of description to code and explain the position and movement of knowledge in the textbooks.

It seems that language plays a critical part in this explanation. According to Coffin (2010:2), "language can stand between a student and success in school learning". She illuminates how the texts students read and write denote or make visible how language functions in helping learners build content. Special attention is given to nominalisation as one of the language resources, as gaining control over it is essential for getting to grips with the decontextualised language in academic discourse (Coffin, 2010:5).

Methodology

Epistemological and ontological assumptions

The way we understand the world to be structured and constituted (the ontological), consequently sets boundaries around the way we gain knowledge ofit (the epistemological). Knowledge-making in critical realism acknowledges that the study is a reasonable attempt to deliver an interpretation of progression. It also acknowledges that some interpretations are fallible as new evidence and truths surface with greater time and investigation, but at the very least it offers information where it is scant (Wheelahan 2010).

This study does not claim generalisable results but rather offers an interpretation of the sample of texts that are analysed here. I attempt to be objective as a researcher involved in several coding levels; I do acknowledge that the absence of a second coder does constitute a limitation to the study. Another researcher could come up with different data from the same texts. I acknowledge that the reliability of the various instruments can be compromised if the coding of the texts is inconsistent because of human error, coder variability (within coders and between coders), and ambiguity in coding rules. However, I argue that in any study there is always a margin of error and that, as a social realist, I offer an interpretation which, to my knowledge, is based on honesty.

Data already publicly available in textbooks reduces ethical considerations. I include the publishers and writers in the reference list but refer to them as text 1 or grade 3 to text 7 or grade 9. Where I include scans from the textbooks, I include a full reference.

The approach and analysis

The study is located within the interpretive paradigm, utilising the methodology of content analysis. This method allows for the content of communication to serve as a basis of inference, from counts to categorisation (Cohen et al. 2007:197). To enhance the study's plausibility and credibility its design is fully described for replication:

• Preliminary level: I write detailed qualitative observational notes of each chapter in the form of a narrative. I note the distribution of content into several pages and paragraphs on a specific topic, their type, format, space, and the amount of information to gauge the complexity, quality, and depth. I categorise 'time and space' to denote context and chronology to describe differences. Maton's (2013) concepts of 'semantic gravity' and 'semantic density' provide a useful language of description to explain the shift in the context of knowledge (semantic gravity) or in meaning (semantic density).

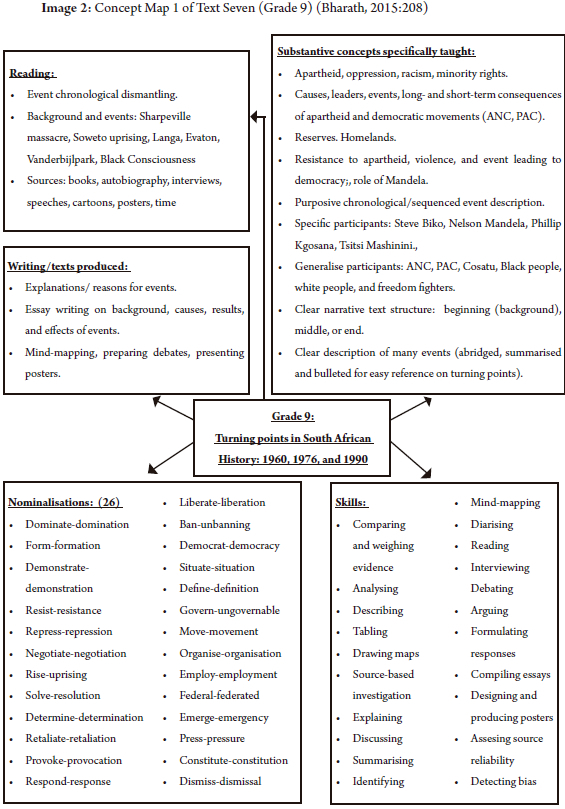

• Demarcation techniques to identify substantive knowledge are employed. Topics, headings, word boxes or word banks, stories and explanations in textual format, pictures, maps, and other visuals including illustrations, sources, activities, and tasks are allotted into coding categories and organised into concept maps (see Image 2).

• Data is sorted by key terms, space (context under study), time and chronology (important historical dates), the number of participants, and important events.

• New vocabulary and nominalised words/concepts/terms and the readability of the texts are recorded and compared.

• Skills that learners would require as they engage with new content are recorded.

• Finally, comparative tables across grades are formulated outlining the differences in the categories.

Sampling

The selection and promotion of textbooks at schools

South African textbooks are the result of a complex interplay between the national curriculum, provincial education departments, textbook authors, publishers, and evaluation committees (Stoffels, 2007). CAPS-compliant textbooks that meet departmental criteria are included in the Department Catalogue for Learner and Teacher Support Material in either the GET or FET band. Teachers have the autonomy to select their textbooks which prioritise the curriculum, inclusion of learner-centred and activity-based exercises, as well as a teacher guide and aligned learner book. For this study, seven graded CAPS-compliant textbooks listed on the Department Catalogue for LTSM, from grades 3-9 were purposively sampled as they were conveniently accessible and purchased in bulk at the researcher's school, popular choices at local and district schools, and recommended by senior educators. There is no dedicated history textbook for grade 3 but their life skills textbook includes introductory ideas related to foundational historical concepts. The remaining choices for grades 4-9 combine both history and geography in one textbook, each featuring unique content, scope, and time. One chapter per text telling the history of South Africa in chronological order was selected for analysis.

The seven texts and seven chapters constitute acts of aggregation which Weber (1990, in Cohen et al., 2007) identifies as a compromise in reliability. Whole text analyses are desirable but are time-consuming with copious amounts of data generated. To avoid human error, the classification of the information ought to be consistent. Words are innately ambiguous and the danger of different coders 'reading' different meanings into them can arise. Thus, the researcher's 'language of description' is made explicit, coding and placement meticulous, and the data checked so that errors do not arise.

Findings

This study finds a clear progression of the substantive knowledge across the grades. The language becomes increasingly dense and abstract. Earlier themes of history 'about me' is very localised (context-bound) and presented in everyday knowledge. Later grades reveal in-depth, specialised, themes like the 'History of South Africa' which includes information about the apartheid struggle, highlighting the nature of the events leading to the collapse of apartheid, and the advent of democracy. The learners are transported in the text from their immediate environment to areas outside of their town, city, province, and country (decontextualised learning). Individual people are studied in depth while some are recognised in their groups, like the San. Depending on the role of the group or the individual and how significant their interactions were, they are remembered and respected by history, particularly the heroes of the political struggle for democracy.

Textbooks used in earlier years are found to be nontechnical and involve simple clauses that can be read with ease while texts engaged in later years present technical vocabulary with dense information. Observed in the texts are abstract terminology, finer print, and a greater number of pages. While posters, maps, photographs in black and white and colour enhance the visual appeal of textbooks, the complex nature of political cartoons is also showcased.

The concepts extracted from grade 3 to grade 9 expand in number and semantic density. The events in history are influenced by the arrival of settlers in South Africa. Their relationships with the natives also created cause for more events and shared experiences, creating multiple perspectives in history. The participants can be generalised in their collective names such as 'Boers' or 'Afrikaners' or they can be specific such as Albert Luthuli' and 'Nelson Mandela'. Both the generalised participants and specific people under study increase in the grade continuum. The blocks of learning to construct a story of the past are created in small increments, event by event, and number of people that construct a story of the past.

Learners in grade 3 learn about the local history of their environment, first engaging with everyday pictures of families and people. In grade 4, learners read about how stories can be constructed by gathering information from objects in the environment (evidence). They are shown how visual, written, and oral elements sourced from magazines, newspapers, and interviews with people can be utilised to understand the past. In grade 5, learners explore the San lifestyle by analysing images of the San people and depictions of archaeological discoveries, enabling their historical understanding of the San culture.

The context then transitions from the early settlements of the Limpopo Valley and the early African societies to the exploration of trade and globalisation in grade 6. At this level learners require advanced skills as they engage with map analysis, exploration, and trade. This is indicated by the nature and complexity of the questions posed to learners as they navigate through the texts pointed to. In the grade 6 textbook, the maps are used to introduce learners to simple positions of countries and continents, exploration, and routes followed by European explorers. The lens widens substantially to penetrate closer into South Africa, centralising the focus on the Cape. The story is taken to the Cape where colonisation becomes the theme of change. Everyday words like 'transport' and 'harbor' in grade 3 shift to 'European exploration' in grade 6 and then to 'Black Consciousness' in grade 9.

Engaging with concepts like 'colonisation' and 'dispossession' in the Cape also requires a certain maturity and ability to understand. Its purposive placement in the grade 7 year of study and the textbook serve to build on what was placed before this. The maps, pictures, and drawings that are presented in the grade 7 text build on earlier images found in lower-grade textbooks. Maps included also have more complex information. The grade 7 textbook requires augmented skills as learners are required to write explanations and produce paragraphs on their understanding of 'colonisation' and the 'warfare between indigenous populations and the immigrants. These activities require an understanding of different sub-components or elements such as rainfall patterns, climate, population distribution, and temperature which influence the lifestyle and location of the people in South Africa. These circumstances resulted in competition for land, resources, and subsistence, as people of that era depended on cultivating their food. The advanced and complex thinking in some activities denotes a highly proficient learner whose ability must be aligned with the task expectation.

The context, background, circumstances, and events, as well as concepts like 'repression' and 'negotiation' in the higher grades require analysis and explanation. Reading and engagement become more rigorous in grade 8 with the introduction of diagrams and political cartoons which require greater analysis, explanation, and interpretation. Timelines advance to include more information across greater periods about events out of the learners' context (decontextualisation). There are more photographs and posters for reading and analysing which require an informed critical reader. Complexity in grade 8 written tasks is even greater, as learners are requested to create timelines, posters, and mindmaps which require an understanding of the dimensions, content, style, criteria, and structure of the text to produce it. Knowledge and understanding of the event must proceed before the learner tackles the task. Learners have to write definitions and explanations that involve a comprehensive understanding of the background, changes to the economy, context, and circumstances surrounding the Mineral Revolution. They have to provide reasons for and evaluate the circumstances of the event.

In grade 9, there are extracts from autobiographies, interviews, and speeches that require that a learner be proficient in language to engage with high-level tasks. The tasks require learners to be able to read at advanced levels to undertake a study of the background to events such as the Sharpeville massacre, the Soweto Uprising, and the circumstances at Langa, Evaton, and Vanderbijlpark. Temporal and spatial advancement, as well as increased language competence, is noted in the transition from common sense knowledge (immediate) to uncommon sense knowledge.

Writing production required in grade 9 in this sample of textbooks is the most complex, with learners required to write essays on the background, causes, results, and effects of a particular event. They are also required to produce mind maps and present debates and posters on the topic in a very structured manner. These tasks require time to plan, design, and present.

Vocabulary becomes more semantically dense and specialised to history (universal historical concepts like colonialism). Language is couched in words, and words are sometimes simple and everyday language and at other times semantically dense and abstract. A word like 'colonisation' is a semantically dense concept that has a universal meaning. The concept of 'colonisation' is also a specific abstract idea that is tied to a multitude of contexts. For example, 'colonisation' in grade 7 has both a contextualised meaning (in southern Africa) and a decontextualised meaning where different countries have colonised continents further away.

The accessibility of words or concepts hinges on their connection to a learner's context, resulting in a strong semantic grasp (contextualised). Conversely, weak understanding due to multiple meanings or lack of everyday relevance results in strongly decontextualised knowledge. Increasing complexity is the overall trend of the advancing grades. The use of source analysis, bias detection, and critical argument in the type of essays learners are required to write is in line with Greer's (1988:21) contention that writing in history "needs to reflect the disciplinary thinking of constructing arguments and reaching conclusions through the use of evidence, critical thinking, and a detailed analysis of the context and origin of evidence" (cited in Schleppegrell, 2012). According to the CAPS Social Sciences Policy Statement (DoE, 2011c) for grades 7-9, the learner has to demonstrate length and complexity through the grades stipulated by the language document. Thus, history knowledge with dense vocabulary, subject-specific terminology, and complex sentence structure can create challenges. Concepts need unpacking through supportive language instruction for enhanced comprehension, fluency, and historical understanding.

How the texts are nominalised

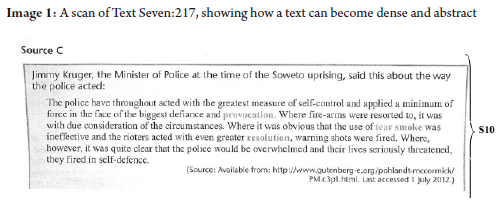

Nominalisation refers to the language resources within a text that adds to its complexity, abstraction, and density. The analysis shows a steady increase in nominalisation across grades, becoming a key principle for charting progression across texts. Words that are dense in meaning and specialised to history can be context-bound and understood if related to an event. This study, thus, claims that abstract concepts in a text remain abstract until their meaning is unpacked and substantiated. A concept like 'resistance movement' can best be understood in a context such as that of the apartheid era. It also requires extensive explanation and foundational knowledge. It is also clear that significant nominalisation is tied to ability, grade level, and the maturity of learners. Image 1 below shows how nominalisation effectively increases the abstraction and density of a text.

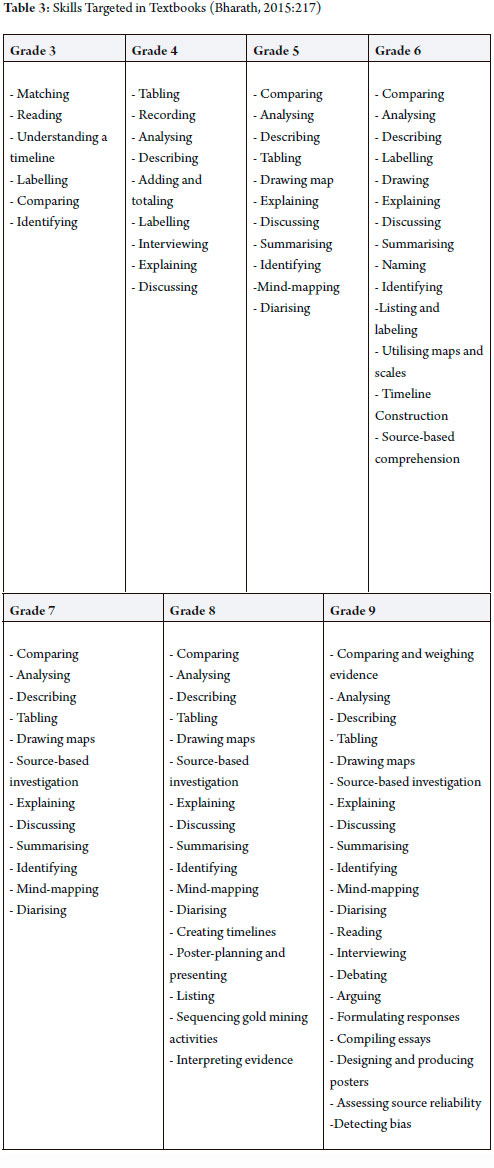

In Image 1, there is a visible increase in the density and abstraction of the text. 'Defiance' is used instead of 'defy', 'provocation' instead of 'provoke', 'consideration' instead of 'consider', and 'resolution' instead of 'resolve. This type of writing would necessitate a reader who cannot only identify the word but can also grasp its meaning in the context. Image 2 below shows how nominalisation is built into the concept map. Seven conceptual maps are harvested for each of the textbooks and then each category on the map is collated on tables for comparison. Table 3 which follows Image 2 shows how increasing skills are collated on a table.

Discussion of findings

Data from conceptual maps and tables indicate that substantive knowledge in the grade continuum commences as highly contextualised and progresses towards a strongly decontextualised form which becomes familiar only if the content is gradually unpacked. The concepts specific to the discipline are the 'metaconcepts' of history that shape it. However, there are other 'concepts' or 'terms' such as 'dispossession', 'colonisation', and 'resistance' which fall into a general yet historical definition of the concept. These concepts are related to the topics that are being covered in the curriculum and text. On closer examination they are shown to be linked as a 'specialised' language to history. Words like 'gravity' and 'potential energy' are linked to natural science like 'respiration' and 'reproduction' are to biology. Similarly, concepts are linked to 'history' and while these may not seem different in complexity, each of the words or concepts is attached to levels of abstraction and understanding.

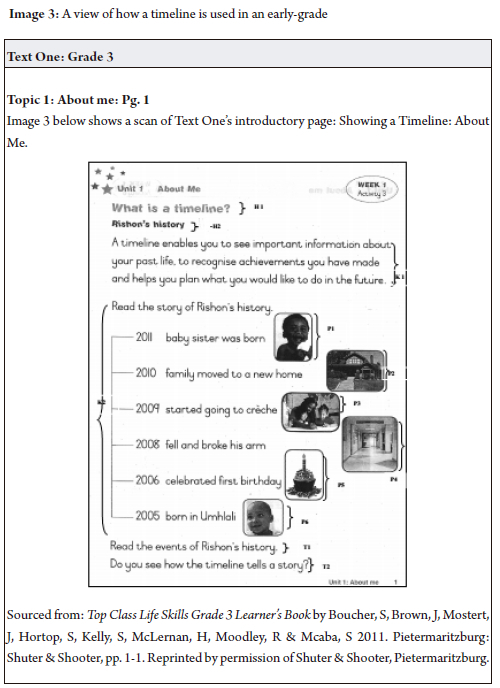

For instance, the historical concept of a 'timeline' at an introductory level is presented differently in higher grades. This is illustrated by the example below showing the use of a 'timeline' in a foundational grade. The grade 3 historian learns chronologically in events and language that is concrete and strongly contextualised. Higher grades present more complex timelines. In the grade 8 textbook, a single timeline presents decontextualised knowledge in subject-specific language. There are a large number of facts about many personalities, and their important contributions over a large space of time are presented in the same timeline. It requires not only an understanding of a timeline but also that the learner be highly proficient in comprehending various periods, events, and personalities. Image 3 shows a view of how a timeline is presented in the earlier grade:

Chronology and time appear as the main signifiers in the advancement of certain understandings. The struggle for democracy in South Africa can only be understood against the background of the apartheid history. In temporal terms this would amount to learning about the apartheid struggle before democratic victory. The concept of 'land dispossession' in grade 8 in South African history cannot be understood unless the earlier grade 5 explanation of the lifestyle, livelihood, location, and subsistence of the indigenous inhabitants of South Africa is properly understood. The African societies (Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe) in grade 6 cannot be thoroughly understood unless learners understand how the archaeological findings assisted in the construction of the story of the San. The very same procedures or archaeological excavations led to the discovery of Mapungubwe. Any conceptualisation of South African or African trade cannot be seen from a historical perspective without first understanding the earliest ivory trade along the East Coast of Africa emanating from the early African societies. With the advent of globalisation, Marco Polo's travel is placed alongside the trade of African societies because both events transpired concurrently. The placement of these topics in the same chapter of the grade 6 text is purposive. The complexity of concepts aligns with the chronological progression of South African history.

The Federation of South African States was a consequence of 'colonisation' and 'land dispossession. Therefore, grade 8 learners only learn about the 'federation' after 'colonisation' in grade 7. Maturity and development are also related to the kinds of concepts taught at different grades. For instance, 'political power' is only considered in grade 8 when the learner is mature enough to understand and assimilate this concept. It is only after this understanding of 'political power' that the idea of 'resistance movements', 'racism', and 'democracy' can be fully conceptualised. It appears that the order of concepts is contingent on the chronological advancement of historical events where learning about one event is a prerequisite for the next.

In grade 7, the 17th and 18th century social, political, and economic upheavals are explored after the colonisation of southern Africa. In grade 8, the Mineral Revolution and all its complexities provide details of the events in the 1880s. This lengthening and broadening tendency in history knowledge is further augmented in grade 9, when boundaries extend further to encompass the study of the turning points in South African history since 1948, including larger time study periods and greater numbers of participants after colonisation. Events, told from a variety of viewpoints, make for interesting multi-perspective history. Time and space, therefore, are important signals of progression in both substantive and procedural knowledge. History appears to be a subject that builds knowledge both 'vertically' and 'horizontally. The number of concepts increases and within each concept is substantial or dense meaning that can be associated with various other contexts. This is why 'colony' can be understood as the Cape becoming a colony of Britain. It can also be associated with various colonies around the world without being confined by temporal or political borders.

Engineering a way to 'measure' and 'describe' the differences in the 'conceptual demand' of the textbooks is a challenging task. In this regard, Maton provides the concept of semantic gravity to describe the shift from contextualised to decontextualised knowledge, which he argues is essential to cumulative learning (Matruglio et al., 2012 ). Bertram (2014:7) recommends beginning with relatable, concrete narratives rather than abstract concepts, especially in lower grades. While this approach is evident in textbooks, it raises questions about students' readiness to understand and engage effectively.

Recommendations

There is a need for a review of teaching and publishing strategies. Textbooks should feature accessible language devoid of abstract vocabulary and convoluted sentences. Publishing books at more accessible levels is a recommended strategy to promote learning across different languages. The significance of language translation is imperative in this context. Textbooks can be translated informally and formally for electronic circulation through social media platforms. Teacher awareness of context and language differences is important as they cannot assume uniform information processing capabilities amongst their learners. The teacher becomes the agent through which connections are made between existing knowledge and new material, effectively levelling the field and breaking down the context and content.

While customising instructional methods to accommodate diverse contexts and barriers to learning, interactive digital resources can be incorporated. The use of documentaries, audio books, videos, as well as QR codes to explain specific contexts can supplement resources. The Department of Education's initiative of departmental workbooks for grades 1 to 9 (mathematics and English) can be supported by history workbooks narrating South African stories, building on key methodologies and substantive knowledge. Subject-specific words can be creatively taught through the use of a history glossary book or dictionary. Graphic organisers can be used to 'tell' a story through symbols and pictures.

Additional research is warranted to ascertain the grasp ofhistorical concepts by second-language learners, as well as the prevalence of these in matric history. Regular assessment and learner responses on comprehension abilities specific to history can elicit feedback on these levels. Targeted reading interventions for students who need support can be implemented. Reflective logs can give teachers an idea of how learners have learnt and how teaching can be improved.

Conclusion

This study argues that complex historical concepts and language in textbooks may hinder learners' interpretation of historical content. Some historical elements are linked to culture and language can impede understanding of different contexts and periods. Differences in instructional language can hamper the progress of less proficient learners and prevent them from expressing their ideas and empathy regarding historical events. This can disconnect them from the subject content and reduce their enjoyment of the subject. The study brings to light the linguistic inequity in South Africa and the need to monitor learners who engage with one of the 11, now 12 official languages. Since materials of historical significance are conveyed in the English language, the question of how learners relate to them is relevant. Academic challenges may be attributable to language factors rather than cognitive deficit

References

Arendse, L. 2019. The South African Constitution's empty promise of "radical transformation": unequal access to quality education for black and/or poor learners in the public basic education system. Law Democracy and Development, 23:100-147. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2077-4907/2019/Idd.v23@5. Accessed on 14 July 2023. [ Links ]

Auerbach, F.E. 1965. The power of prejudice in South African education. Cape Town: A. A. Balkema. [ Links ]

Basic Education Rights Handbook - Education Rights in South Africa. 2017. Chapter 15, SECTION 27. Braamfontein, Johannesburg. pp. 266-272. [ Links ]

Bernstein, B. 1971. On the classification and framing of educational knowledge. In: Young, M.F.D., ed. Knowledge and control: new directions for the sociology of education. London: Collier-Macmillan. pp. 47-69. [ Links ]

Bernstein, B. 1996. Pedagogy, symbolic control and identity: theory, research, critique. London: Taylor & Francis. [ Links ]

Bernstein, B. 1999. Vertical and horizontal discourse: an essay. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 20(2): 157-173. [ Links ]

Bertram, C. 2008. "Doing History?" Assessment in history classrooms at a time of curriculum reform. Journal of Education, 45:155-177. [ Links ]

Bertram, C. 2009. Procedural and substantive knowledge: some implications of an outcomes-based history curriculum in South Africa. Journal of comparative education, history of education and education development, 15(1):45-62. [ Links ]

Bertram, C. 2014. How do school history curricula map disciplinary progression? Paper presented at the Basil Bernstein 8 Symposium, Nagoya, Japan, 10-12 July 2014. [ Links ]

Bertram, C., & Bharath, P. 2011. Specialised knowledge and everyday knowledge in old and new grade 6 history textbooks. Education as Change, 15(1):63-80. [ Links ]

Bharath, P. 2009. A study of knowledge representation in grade 6 history textbooks before and after 1994. Curriculum Studies. University of KwaZulu-Natal: Pietermaritzburg. [ Links ]

Bharath, P. 2015. An investigation of progression in historical thinking in South African history textbooks. Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal. (Thesis - PhD). [ Links ]

Bloch, G. 2009. The toxic mix: what's wrong with South Africa's schools and how to fix it. Cape Town: Tafelberg-Uitgewers. [ Links ]

Boucher, S., Brown, J., Hortop, S., Kelly, S., Mcaba, S., McLernan, S., ... Mostert, J. 2011. Top class: life skills for grade three, Learner's Resource Book. Pietermaritzburg: Shuter & Shooter. [ Links ]

Coffin, C. 2006. Learning the language of school history: the role of linguistics in mapping the writing demands of the secondary school curriculum. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 38(4):413-429. [ Links ]

Coffin, C. 2010. Language support in EAL contexts. Why systemic functional linguistics? Special Issue of NALDIC Quarterly. NALDIC, 8(1):6-17. [ Links ]

Cohen, L., Manion, L, & Morrison, K. 2007. Research methods in Education. 6th ed. Abingdon: Routledge. [ Links ]

Counsell, C. 2018. Taking curriculum seriously. Perspective Article. September 12. Impact Articles. https://my.chartered.college/impactarticle/taking-curriculum-seriously/ Accessed on 10 June 2023. [ Links ]

Crawford, K. 2003. The role and purpose of textbooks. International Journal of Historical Learning, Teaching and Research, 3(2):5-19. [ Links ]

Cummins, J. 2015. Second language acquisition-essential information. http://www.esl.fis.edu/teachers/support/cumin.html. Accessed on 15 February 2015. [ Links ]

Dean, J. 2004. Doing history: theory, practice and pedagogy. In Jeppie, S., ed. Toward new histories for South Africa: on the place of the past in our present. Cape Town: Juta Gariep. pp. 99-116. [ Links ]

Department of Education. 2000. Report of the history/archaeology panel to the Minister of Education. Ministry of Education. Pretoria: Department of Education. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education. 2011a. National Curriculum Statement Grades 4-6 Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement. Home Languages. Pretoria: Department of Basic Education. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education. 2011b. National Curriculum Statement Grades 4-6 Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement. Social Sciences. Pretoria: Department of Basic Education. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education. 2011c. National Curriculum Statement Grades 7-9 Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement. Social Sciences. Pretoria: Department of Basic Education. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education. 2023. Progress in international reading literacy study (PIRLS) 2021: South African preliminary highlights report. Pretoria: Department of Basic Education. [ Links ]

ENCA News Live 2023. 27 June. South Africa's education crisis. Minister updates on developments in the education sector. http://youtu.be/ejLM2AOgvqo. Accessed on 27 June 2023. [ Links ]

Engelbrecht, A. 2005. Textbooks in South Africa from apartheid to post-apartheid: ideological change revealed by racial stereotyping. Paper presented as background reading at an international conference: Education, social cohesion and diversity, Washington DC, [Conference Date: circa2005]. [ Links ]

Engelbrecht, A. 2008. The impact of the role reversal in representational practices in history textbooks after apartheid. South African Journal of Education, 28:519-541. [ Links ]

Ensor, P. & Galant, J. 2005. Knowledge and pedagogy: sociological research in mathematics education in South Africa. In: Vithal, R., Adler,J. & Keitel C. eds. Researching mathematics education in South Africa. Perspectives and possibilities. Cape Town: HSRC Press. [ Links ]

Friedman, M., Ranby, P. & Varga, E. 2013a. Solutions for all. Social sciences. Grade 8. Gauteng: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Friedman, M., Ranby, P. & Varga, E. 2013b. Solutions for all. Social sciences. Grade 9. Gauteng: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Hoadley, U. & Jansen, J. 2009. Curriculum: ongoing knowledge for the classroom. 2nd ed. Cape Town: Oxford University Press & SAIDE. [ Links ]

Kissack, M. 1997. Irony as objectivity: orientations for history teaching in post-apartheid South Africa. Curriculum Studies, 5(2):213-228. [ Links ]

Kwazulu-Natal Department of Education. 2014. Learning and teaching support material. Textbooks catalogue for 2009 academic year. General education and Training (GET): grades 4-7. Pietermaritzburg: KZN Department of Education. [ Links ]

Lee, P. & Shemilt, D. 2004. I just wish we could go back in the past and find out what really happened: progression in understanding about historical accounts. Teaching History, 117:25-31. [ Links ]

Lévesque, S 2008. Thinking historically: educating students for the twenty-first century. Toronto: University of Toronto Press Incorporated. [ Links ]

Loewen, J.W. 1995. Lies my teacher told me: everything your American history textbook got wrong. New York: The New Press. [ Links ]

Martin, G. 2012. Thinking about historical thinking in the Australian curriculum: history. Victoria: University of Melbourne. [ Links ]

Martin, J.R. 2013. Embedded literacy: knowledge as meaning. Linguistics and Education, 24:23-37. [ Links ]

Maton, K. 2013. Making semantic waves: A key to cumulative knowledge-building. Linguistics and Education, 24(1):8-22. [ Links ]

Matruglio, E., Maton, K. & MartinJ.R. 2012. Time travel: the role of temporality in enabling semantic waves in secondary school teaching. University of Sydney, Australia. Linguistics and Education. http://www.legitimationcodetheory.com/pdf/2013Matruglio%20et%20al.pdf. Accessed on 21 February 2015. [ Links ]

Morgan, K. & Henning, E. 2011. How school history textbooks position a textual community through the topic of racism. Historica, 56(2):169-190. [ Links ]

Motshekga, A. 2009. Statement to National Assembly by Minister of Basic Education on Curriculum Review Process. http://www.education.gov.za/dynamic/dynamic.aspx?pageid=306andid9148. Accessed on 21 February 2015. [ Links ]

Naidoo, D. 2009. Case studies of the implementation of "progression and integration" of knowledge in South African schools. Education as Change, 13(1):5-25. [ Links ]

Oppong, C., Adepong, A. & Boadu, G. 2022. Practical history lessons as a tool for generating procedural knowledge in history teaching. Yesterday & Today, 27:143-161. [ Links ]

Ramoroka, D. & Engelbrecht, A. 2015. The role ofhistory textbooks in promoting historical thinking in South African classrooms. Yesterday & Today, 14:99-124. [ Links ]

Ranby, P. & Zimmerman, A. 2012a. Solutions for all social sciences. Grade 4. Gauteng: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Ranby, P. & Zimmerman, A. 2012b. Solutions for all social sciences. Grade 5. Gauteng: McMillan. [ Links ]

Ranby, P. & Zimmerman, A. 2012c. Solutions for all social sciences. Grade 6. Gauteng: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Ranby, P. & Varga, E. 2013. Solutions for all social sciences. Grade 7. Gauteng: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Rata, E. 2016. A pedagogy of conceptual progression and a case for academic knowledge. British Educational Research Journal, 42(1):168-184. [ Links ]

Schleppegrell, M.J., Greer, S. & Taylor, S. 2008. Literacy in history: language and meaning. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 31(2):174-187. [ Links ]

Schleppegrell, M.J. 2012. Systemic functional linguistics: exploring meaning in language. In: Paul, J.G. & Hanford, M. eds. The Routledge handbook of discourse analysis. New York: Routledge. pp.: 21-34 [ Links ]

Schleppegrell, M.J., Achugar, M. & Oteiza, T. 2012. The grammar of history: enhancing content-based instruction through a functional focus on language. Tesol Quarterly, 32(1):67-93. [ Links ]

SCHP. School council history 13-16 project 1976. A new look at history. Edinburgh: Holmes McDougall. [ Links ]

Seixas, P. 2006. Benchmarks of historical thinking: a framework for assessment in Canada. Centre for the study of historical consciousness. British Columbia: UBC. [ Links ]

Stoffels, N.T. 2007. A process-oriented study of the development of science textbooks in South Africa. African Journal of Research in SMTEducation, 11(2):1-14. [ Links ]

Wasserman, J. & Roberts, S.L. 2022. Making good use of textbooks: introduction to the special issue on teaching with history textbooks. Annals of Social Studies Education Research for Teachers, 3(2):1-4. [ Links ]

Wheelahan, L. 2010. Why knowledge matters in the curriculum. A social realist argument. London & New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Young, M. 2008. Bringing knowledge back in: from social constructivism to social realism in the sociology of education. Abingdon: Routledge. [ Links ]

1 Findings extracted from the researcher's broader study, P. Bharath, "An investigation of progression in historical thinking in South African history textbooks" (PhD., UKZN, 2015).

2 South Africa has eleven official languages which are recognised as equal.

3 Home language, the medium of communication at home, is not necessarily the language of learning and teaching (LOLT) at school.