Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Yesterday and Today

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9003

versão impressa ISSN 2223-0386

Y&T no.29 Vanderbijlpark Jul. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2223-0386/2023/n29a4

ARTICLES

"Myth" or "construct"?: What students are learning about race in the South African history classroom

Natasha RobinsonI; Nicholas KerswillII

IWalter Sisulu University, Mthatha, South Africa. Orcid: 0000-0003-0394-0084; go22691@bristol.ac.uk

IISEK-Dublin International School, Co.Wicklow, Ireland. nkerswill@claremonthigh.co.za

ABSTRACT

History education in post-apartheid South Africa addresses topics that are highly salient to the concept of race. To make sense of colonialism, slavery, the Holocaust, and most notably apartheid, students require an understanding of what race is, and how it has been used to justify discriminatory and unjust behaviour. The South African Curriculum and Policy Statements for Grade 9 History therefore devotes two hours to a topic on "the definition of race" (Department of Basic Education [DBE], 2011a: 43).

However, what are students learning about 'the definition of race' from their history education? In this article, we draw on our experience as a history educator and history education researcher to argue that students often develop inaccurate and unhelpful understandings of race. This is partially since both the South African history curricula and textbooks describe race as a "myth" (DBE, 2011a, 43; Bottaro, Cohen, Dilley, Duffett, & Visser, 2013) with no scientific or evolutionary basis. Hence, students who learn that race is a 'myth' understandably struggle to understand discourses and policies that refer to racial identity and are at risk of misunderstanding theories of evolution.

While we agree that the concept of race has no legitimate scientific basis, we nonetheless argue that students require an historical understanding of race; one that demonstrates how racial identities have been constructed in different ways and for different purposes over time. Such an approach would introduce students to the extensive historiography of the construction of race (e.g. DuBois, 1940; Dubow, 1995). By understanding race as a construct rather than a myth, we suggest that students will be better able to engage with the legacies of racialised violence as well as the ways in which racial identity is a legitimate source of meaning for many South Africans.

Keywords: South Africa; Race; History Education; Ethnography

Introduction

"Everyone is saying you shouldn't base university entrance on the colour of your skin, they should base it on your marks", says Amy. "People keep on saying that but then they don't stand up for it, do you know what I mean?"

She looks at me somewhat exasperated as we sit in her Grade 9 History classroom, the afternoon sun streaming through the high sash windows. We are discussing university admissions - a hot topic in this academically competitive Cape Town school - and inevitably the issue of race arises: "The whole world is basing everything on race but really it's just a pigment."

We have heard this reasoning many times in our conversations with young South Africans. It is one of several misunderstandings that stem from the way in which race is discussed in history classrooms. In post-apartheid South Africa, where racial discrimination has been a foundation of centuries of violence and injustice, many educators are eager to reinforce a message of non-racialism. This approach is consistent not only with the African National Congress' (ANC) policy of non-racialism, but also with the South African Curriculum and Policy Statements (CAPS) that advocate "human rights and peace by challenging prejudices involving race, class, gender, ethnicity and xenophobia" (DBE, 2011a: 9). As a result, the South African CAPS refer to race as a "myth" with no scientific basis (DBE, 2011a: 43).

However, in this article we draw on hundreds of hours of history teaching and observation, as well as a detailed analysis of CAPS documents and several Grade 9 History textbooks, to question the appropriateness of the CAPS definition of race in the Grade 9 History curricula. Indeed, we argue that the understanding of race as a 'myth' or 'just a pigment' not only prevents students like Amy from engaging with the structural legacies of apartheid, but also results in several dangerous misunderstandings regarding race and evolution. We also suggest that this approach is ahistorical and that it ignores the substantial historical research that details how race as a concept, has been constructed over time.

The argument presented here is not the result of a defined research project, rather it represents the outcome of observations and reflections from several years of professional experience as a history teacher in Cape Town (Nicholas Kerswill) and a history education researcher in South Africa (Natasha Robinson). All observations conducted by Natasha that contributed towards this article were granted ethical permission by both the University of Oxford and the Western Cape Department of Education. The names of all students and schools mentioned in this article are pseudonyms.

This study is structured as follows: First we discuss how race is discussed and defined in the South African CAPS and in popular history textbooks. We then describe some of the common misunderstandings that we have observed in history classrooms because of the ways in which race is defined. In the third section we outline some of the ways in which history textbooks in the UK and historians internationally, have discussed the construction of race. The study is concluded with a suggestion that history teachers and curricula should rely less on the scientific claim that race does not exist and instead, help students to understand the historical ways in which race as a concept, has been constructed.

How the South African history curriculum teaches the complexities of race

History education in post-apartheid South Africa addresses topics that are highly salient to the concept of race. To make sense of colonialism, slavery, the Holocaust, and most notably apartheid, students require an understanding of what race is, and how it has been used to justify discriminatory and unjust behaviour. The South African CAPS for Grade 9 History therefore devotes two hours to a topic on "the definition of race" (DBE, 2011a: 43) as an introduction to studying apartheid.

However, the approach to teaching racism outlined by CAPS draws far more from natural science than it does from the humanities. Teachers are asked to cover two points: "Human evolution and our common ancestry" (DBE, 2011a: 43) and "The myth of race" (DBE, 2011a: 43).

The CAPS document clarifies this evolutionary focus on race by stating: People often ask how understanding human evolution helps us. The issue of 'race' still vexes South African society today. Scientists say that 'race' is a cultural or social construct and not a biological one. Apartheid ideology, for example, selected superficial criteria of physical appearance to create categories of people and used these to classify people into 'population groups'. The study of human evolution shows us that we share a common ancestry - we are all Africans in the sense that we all descendedfrom ancestors who lived in Africa as recently as 100 000 years ago (DBE, 2011a: 43).

In this clarification, the CAPS document acknowledges that race is a "social construct" (DBE, 2011a: 43), yet does not define what is meant by "construct". It then continues to place emphasis on "the study of human evolution" (DBE, 2011a: 43) to argue that all humans share a common ancestor.

This natural science-focused approach to teaching about race is also reflected in the presentation of race in history textbooks. The Oxford University Press textbook (Bottaro et al., 2013: 124), for example, discusses the development of hominids over approximately four-million years, accompanied by a picture showing the evolution of human beings. It speaks about the Cradle of Humankind in Africa and how early modern humans spread from Africa to the rest of the world. The Maskew Miller Longman textbook (Earle, Keats, Edwards, Sauerman, Roberts & Gordon, 2013: 158) devotes a page to "The Human evolution and our common ancestry", with a lengthy discussion of Australopithecines (otherwise known as 'southern ape'). The Vivlia textbook (Jardine, Monteith, Versfeld, & Winearls, 2013: 142) similarly describes how "our ancestors evolved in Africa, and then spread from Africa into Europe and Asia, and eventually to Australia and the Americas".

The purpose of this brief introduction to evolution is to show students that there are no genetic differences between people of different races. Race - according to the curricula - is therefore a "myth", which the Oxford University Press textbook defines as "a belief that is not based on fact" (Bottaro et al., 2013: 126). However, the terms 'historical construct' or 'social construct' are not used in the Grade 9 textbooks. Race as a concept, is simply described as non-factual, which implies that people who evoke race or are racist, are therefore irrational.

It is notable that CAPS documents do discuss "theories of race and eugenics" in Term 2 of the Grade 11 curricula, when students revisit the history of Nazi Germany and the Holocaust. In Grade 11, the CAPS document re-emphasises the "unscientific bases" on which racial theories lie and which have "been discredited by modern genetic research" (DBE, 2011b: 21). Importantly, it also discusses how notions of race were applied in different ways at different times and in different contexts. However, even within this section which discusses race as a social construct, the "modern understanding of race" is described as the "human genome project" (DBE, 2011b: 21). The curriculum does not discuss how 'modern' South Africans might engage with race as something other than 'unscientific.

History education within South Africa therefore leaves students without a framework for understanding how contemporary society engages with racial identities in meaningful ways. This is particularly true for most South African students who stop studying history after Grade 9, when it is no longer compulsory. The only message that these students are taught is that race is a myth that some people used for the purposes of discrimination.

What are students learning?

The approach to focus on race through a scientific evolutionary lens in a history textbook, and conclude that it is a myth without explaining how such a myth was constructed, presents several challenges in the classroom. As an anthropologist of history education and a South African history educator, we have taught and observed Grade 9 History classes in a total of eleven Cape Town schools (see Dryden-Peterson and Robinson, 2013; Robinson, 2021). From our observations regarding how students engage with ideas of race, we outline three common misunderstandings.

Misunderstanding #1: "Race doesn't exist"

The first misunderstanding - that we commonly observed among White students - is the idea that since race 'doesn't exist', all mention of race must be at best irrational and at worst racist. The idea that 'race is a myth' aligns with a colour-blind agenda that proves comfortable for White students, and which largely absolves them from looking for the deeper structural causes of racial inequality in South Africa. These students challenge discourses concerning 'white spaces' or 'black culture', since to notice how race intersects with lived experience (in ways both oppressive and emancipatory) is to accept the myth.

An understanding of race as myth therefore, reinforces what Conradie (2016: 9) refers to as "power-evasive discourses" which "serve to justify the desire to avoid obtaining knowledge about the way race plays out in society". If all discussion of race is racist, then the relationship between power and race cannot be legitimately investigated or identified. Sue (2013: 666) explain that the fear of appearing racist in public hinders White students' willingness to gain knowledge about the social construction of race and to concede the possibility of new racism. Racism, according to Conradie (2016: 9), is therefore typically confined to anomalous individuals, with the corollary that systemic racism is isolated to a history that ended in 1994 and which has no bearing on the past.

White students who we have observed and taught seemed to baulk at using race as a heuristic for privilege or lack of privilege and instead, preferred to discuss individual circumstances. One of our students in a focus group suggested that a child who is Black and poor may in fact be more privileged than his wealthy White peer, if the Black child has loving parents but the White child has abusive parents. Our students' unwillingness to see race or poverty as structural, reflected Vincent's (2008: 1432) observation that:

Social ills are crafted as problems located within specific individual relationships and the possibilities for social action are thus undermined. The hegemonic liberal humanist discourse insisting that we focus on our "common humanity" erases the specificities of raced experiences and evades the question of who has the power to define that humanity.

Related to this misunderstanding was confusion - on behalf of students of all racial identities - over the ubiquity of racial terminology within South African society and in particular, the idea that race might be legally used to determine opportunities. Affirmative action, most visibly in the form of university entrance, was very upsetting to some students who interpreted it as hypocritical and "reverse racism" (Robinson, 2021: 258).

The curriculum's message that race is a "myth" (DBE, 2011a: 43) reflects a tension within the South African government's position on non-racialism. On the one hand, students were attracted to South Africa's non-racial Constitution1 (Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996: 3) and its commitment to making non-racialism a social reality. Non-racialism appears to be a logical consequence of a belief that race is a 'myth. Yet, on the other hand, students' understanding of race as a myth prevented any acceptance of the ruling party's position that "racial classification cannot be avoided if we are to ensure representivity in the state and in society generally" (African National Congress, 2005). Indeed, this was not surprising given that the only forms of racial classification that students had been exposed to in history class were the Holocaust and apartheid.

The subtle distinctions between non-racialism as a reality vs an aspiration are well articulated by Suttner (2012: 27) who explains that:

The proposition that races do not exist is correct at an ontological level, for the construction of the concept of 'generic human explicitly repudiates the invocation of any predicates whatsoever. But race, like class, therefore both does not exist ontologically (forgeneric humanism) and does exist structurally for it has been and is a mechanism of inequality like class.

To assume - as the CAPS document does - that racial justice will be served from an acknowledgement that race does not exist ontologically, is as misguided as thinking that class inequalities will disappear if we acknowledge that class does not ontologically exist. Instead, Suttner warns that attempts to erase the significance of racial categories raises a danger of premature closure in addressing historic disabilities in all their forms. Suttner suggests that "non-racialism can only be viable if it also recognises and is not in conflict with attempts to address distinct qualities and experiences, particularly disadvantage and disabilities of various groups" (2012: 36). However, this approach to non-racialism can only make sense to students if they are taught about the structural existence of race as well as its ontological non-existence.

Misunderstanding #2: "Evolution didn't happen"

The second misunderstanding that we observed concerns the curricula and textbooks' reliance on theories of evolution to argue that race is a myth. In a highly religious country, such as South Africa, we observed how meaningful conversations about race during history lessons could be easily waylaid as students attempted to reject evolutionary theories in favour of creationism. This becomes particularly challenging given that the widely used Vivlia textbook cites Jared Diamond's The Third Chimpanzee (1991), which some of our students took as evidence of the claim that people used to be monkeys.

From a religious perspective the implication that human beings were monkeys is hugely inflammatory and the classroom discussions can quickly devolve into a discussion regarding the merits of evolutionary theory. When coupled with the absolute terms in which human evolution is described, textbook sections on race begin to feel both unhelpful and unnecessary. Evolution, a controversial theory to many, is used to justify anti-racism, which is a very uncontroversial idea among Grade 9 students.

The reliance on theories of evolution to discuss the nature of race is surprising for two reasons. First, students will not explicitly encounter theories of evolution in their natural science classes until Grade 12. Discussions of evolution in Grade 9 History classes may therefore be the first time that students formally engage with these theories. It is likely that they have not developed the scientific literacy to engage with such challenging and controversial concepts. Second, history educators are rarely trained to teach complex scientific concepts.

Indeed, as Sutherland and LAbbé (2019: 1) argue, even among natural science teachers and learning materials, theories of evolution are poorly taught. For example, they found scientifically incorrect statements in all the curriculum statements and in eight of the recommended Life Sciences textbooks. Such errors included what Sutherland and LAbbé refer to as "evolution on demand" and "survival of the fittest" (2019: 3).

Sutherland and LAbbé (2019: 3) described "evolution on demand" as being characterised by teleological and anthropomorphic thinking in which 1) changing food types or environments cause evolution to occur, 2) individuals evolve 3) within their lifetime and 4) they decide to undergo these changes because they know the changes will be favourable, and 5) this evolution occurs in order to prevent extinction.

Sutherland and LAbbé (2019: 3) describe "survival of the fittest" as implying that 1) only the fittest, or those with favourable adaptations survive, 2) less favourably adapted organisms will die or become extinct, 3) only the fittest will reproduce, while those not considered fit cannot reproduce, 4) all the offspring of those with favourable traits will inherit the favourable traits, and 5) the whole population will eventually be made up of only individuals with favourable traits.

As well as this inaccurate and inadequate learning material, Sutherland and LAbbé (2019: 4) found that Life Science teachers in South Africa were averse to teaching evolution because, a) they lack the content knowledge; b) they experience a conflict between their own religious beliefs and the requirement to teach evolution; and/or c) they are afraid of the reactions of their students or students' parents. Abrie (2010) for example, studied South African student teachers' attitudes towards teaching evolution and found that student teachers were largely religious and rejected the theory of evolution, with only 42% of student teachers participating in Abrie's study agreeing that evolution should be a compulsory part of the Life Sciences curriculum. Similarly, Mpeta, de Villiers and Fraser (2014: 160) found that among Grade 12 Life Science students in the Vhembe District of the Limpopo Province, South Africa, less than half of the students accepted the theory of evolution as scientifically valid.

Given that even Grade 12 Life Science teachers and students struggle to engage with evolution, it is not surprising that Grade 9 History teachers and students find this framing of race as particularly challenging and unhelpful. While we welcome the need for students to learn about theories of evolution, we suggest that using evolution to introduce a topic as contentious as the nature of race seems unwise. Indeed, the inclusion of evolution as an entry point to discussions about race perhaps betrays a bias on the part of the curriculum developers who may not be aware of the challenges of teaching evolution in South Africa.

Misunderstanding #3: "Racial hierarchies exist"

The last misunderstanding is perhaps the most disturbing, although it is not something that we have personally observed. Several scholars (Pandor, 2002: 63; Parle & Waetjen, 2005: 529; Sutherland & LAbbé, 2009: 5) noted that some South African students are misconstruing theories of evolution to conclude that Black people are less evolutionarily advanced than White people. Our sense is that this is not something which teachers are communicating, however, rather what students are interpreting from the textbooks. For example, the Grade 9 History textbooks say that hominids originated in Africa - and were therefore 'African', suggesting that Africans are less evolved humans. Likewise, textbook images show darker-skinned hominids evolving into lighter-skinned 'modern humans'. There is a risk of conflation between White, modern, and human, in contrast to Black, pre-modern, and hominid.

Parle and Waetjen (2005: 529) di scuss this challenge in some depth in relation to the Africa in the World: From Mascence to Renaissance' (AITW) course they were teaching. Launched in 2001, AITW was conceptualised as the 'content' and 'bridging' course on the Pietermaritzburg campus of the former University of Natal. Evolution was covered in this course to emphasise the central role that Africa plays in human development. However, not only did students resist learning about human evolution for reasons of faith, some also perceived evolution as an attempt to assert the 'primitiveness of African people'.

For example, Parle and Waetjen (2005: 529) note that several students accused the instructor:

Of making the claim that Africans were 'closer' to early hominid species, due to their continued residence in the 'cradle of humanity' while other ancestors had migrated and moved on. They perceived that climatic adaptations such as skin colour and hair texture must be indications of'development' or 'advancement' in the case of populations who moved out of Africa. The logic they attributed to the evolutionary scenario seemed to be that the negative aspects of the current African social plight (famine, conflict, HIV/ AIDS) were somehow due to a stagnation associated with natural selection. The instructor also experienced several crude and angry accusations that she was saying that 'Africans were closer to ape ancestors' because they were 'still' in Africa. Finally, a kind of Darwinian ('survival of the fittest') logic was also employed by students to explain why some Africans were now wealthy while others were poor - the new 'free market' post-apartheid environment being the context requiring new 'adaptations'.

Related to this misunderstanding, Parle and Waetjen (2005: 529) also document students drawing the opposite racial conclusions from evolution as the ones described above. Instead, some students consider evolutionary theories as new ways of conceptualising 'racial purity'. Parle and Waetjen report that "Some students felt that the 'out of Africa' thesis was an indication that the only 'pure race' was the 'black man' and that 'all other races' were derivatives" (2005: 529). Furthermore, "this knowledge augmented a 'native/ settler' dichotomy, by increasing the indigeneity of people with dark skin who continued to live on the continent, while augmenting the alienness or foreignness of people from other continental (European, Indian, American) diasporas" (Parle & Waetjen, 2005: 529).

It is interesting to note that students' misunderstandings regarding Africans' failure to evolve, or Africans' racial 'purity', reflect some of the misunderstandings that Sutherland and LAbbé (2009: 5) identified in their analysis of Life Science learning materials. The intention to use evolutionary theory to emphasise the unscientific basis for race therefore risks backfiring. Without students having already developed strong scientific literacy, they may use evolutionary theory to reinforce a belief in racial science.

Towards an historical understanding of race

In a country with such a damaging legacy of racism there is a legitimate need and desire to communicate in the clearest possible terms that racism is irrational and wrong. However, as the examples above show, the language of scientific 'fact' is not always a straightforward way to communicate that message.

Even if evolutionary theory helps students to understand that race is not 'real' in any biological sense, it does not help them to make sense of the highly racialised society that they live in. Crucially, it does not answer the questions that our students pose, such as "Why, of all the races, did White people end up on top?" or even more heart-wrenching, "Why do White people hate us?"

To answer these questions an historical understanding of race is required, rather than simply a scientific understanding. Similarly, we need to move away from describing race as a 'myth' - as though it was a story without clear origins - and start describing race as a construct, which is and has been constructed in different ways throughout time by people with agency. Constructs are defined as concepts that do not exist in objective reality, however, as a result of human interaction. While a scientific explanation can be helpful for explaining that race is a construct, we need an historical explanation to teach students how and why race has been constructed.

WEB DuBois was a leading thinker in regards to the historical construction of race, writing in 1940 that, "it is easy to see that scientific definition of race is impossible" (DuBois, 1940: 137). Instead, DuBois ar gued that:

The discovery of personal whiteness among the world's peoples is a very modern thing, -a nineteenth and twentieth century matter, indeed. The ancient world would have laughed at such a distinction. The Middle Age regarded skin color with mild curiosity; and even up into the eighteenth century we were hammering our national manikins into one, great, Universal Man, withfinefrenzy which ignored color and race even more than birth" (DuBois, 1920: 923).

According to DuBois, the "scheme" of dividing people according to colour was a way in which "white civilization" (1920: 932) could overcome the impossibility of the continued subjection of the White working classes. Advances in education, political power, and increased knowledge of the industrial process were destined to equalise wealth, placing the position of the very rich at risk in "white nations" (1920: 932). DuBois argued that this challenge was overcome through the "exploitation of darker peoples" which offered immense profit, yet, required the invention of "the eternal world-wide mark of meanness, - colour!" (1920: 932).

There are several new resources for teaching an historical approach to how the concept of race was constructed and increasingly, these approaches are being adopted in the USA and UK.2 These approaches draw on a Du Boisian intellectual tradition that understands the construction of racial identities as a justification for African enslavement. As Facing History and Ourselves describes:

Despite the fact that Enlightenment ideals of human freedom and equality inspired revolutions in the United States and France, the practice of slavery persisted throughout the United States and European empires. In the late 1700s and early 1800s, American and European scientists tried to explain this contradiction through the study of "race science," which advanced the idea that humankind is divided into separate and unequal races. If it could be scientifically proven that Europeans were biologically superior to those from other places, especially Africa, then Europeans could justify slavery and other imperialistic practices (Facing History and Ourselves: np).

Within this approach, students are taught that race - although having no scientific basis - was invented for the political purposes of maintaining power and economic superiority.

This historical approach to race is also discussed in a new history textbook on the British Empire that was published this year (2023) in the UK (Kennett et al. 2023). In this textbook, the authors explain:

There is no scientific evidence for race, but race is an important identity for many people. Its definition changes throughout history. The way in which people are grouped into races shifts, as does the way these groups are treated... Race is a 'construct' - its definition changes depending on the meaning people give to it (Kennett et al 2023: 66).

The afore-mentioned textbook goes on to outline how ideas surrounding race changed across four time periods (before 1650, 1650-1800, 1800-1900, and 1900-the present) as well as how these ideas had a changing impact on the British Empire. Particularly interesting is how this textbook describes the ways in which scientific racism justified colonisation since "the British believed they had racial superiority and could colonise other races" (Kennett, Thorne, Barma, Allen, Durbin, Hibbert, Patel, Quinn, Stevenson, Stewart & Yasmin, 2023: 66).

One of the most useful resources for teachers is a Guardian article by Baird (2021, np). The article entitled "The invention of whiteness: the long history of a dangerous idea" argues that White superiority was invented as a way of justifying the slavery of Africans. Previously, such slavery was justified on the basis that these Africans were not Christian, however, as missionaries started to convert enslaved Africans to Christianity, a new justification was required. People who previously would not have identified as White started to do so as a means of legitimating their dominance.

Teaching the historical construction of race in practice

There are few available case studies of how teachers have taught the construction of race in their history classrooms, and certainly more research is required. However, one valuable example from the UK is Kerry Apps article in Teaching History entitled "Inventing race?" (2021). Apps (2021) documents how her Year 8 students used early modern primary sources to investigate the complex origins of racial thinking in the past, in order that students could understand why the experiences of Black people were different during the Tudor/Stuart expansion, and the trade in enslaved peoples.

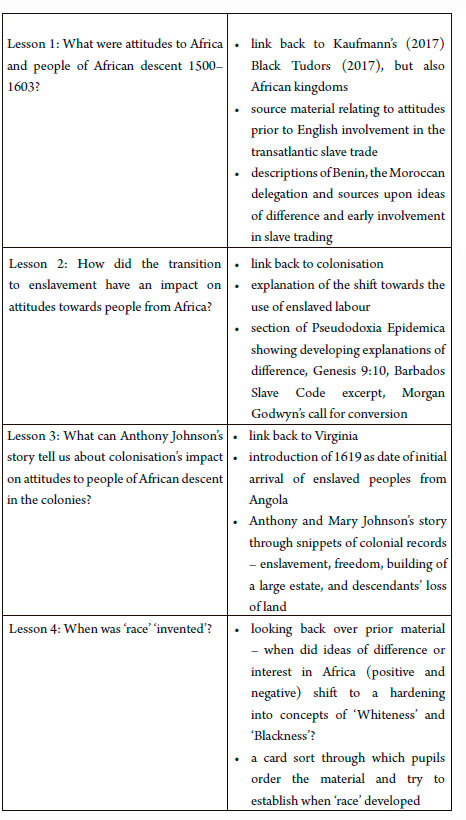

The enquiry that Apps developed for her students spanned four history lessons and the summary can be found in the table below (Apps, 2021: 13):

Apps (2021: 16) documents the positive learning outcomes from her students as a result of this enquiry. She notes that "my students had clearly been able to use the source record to discern a distinct shift between 1500 and 1700. The students perceived that the initially positive reaction of the English to African people such as John Blanke ultimately gave way to the negative implications of the slave codes" (Apps, 2021: 17). Apps goes further to say that, "understanding the historic roots of these ideas is powerful knowledge both because it gives pupils power in understanding subsequent periods and because it equips students to discern and deal with the modern consequences of these ideas" (2021: 18). Examples of students' analysis of the sources following this enquiry can be found in the original Teaching History article (Apps, 2021: 18).

Constructing ideas of race in South Africa

The examples noted above, address the construction of race in Europe and the Americas. There is a conspicuous lack of teaching resources that address the historical construction of race in the South African context. However, this is not because the historiography does not exist. Indeed, the history of the construction of race in Southern Africa is fascinating.

Saul Dubow (1995) (now a professor at Cambridge University) published the ground-breaking monograph entitled Scientific Racism in Modern South Africa. This book details the extensive debates that were ongoing throughout the 20th century among physical anthropologists who were trying (and failing) to develop a coherent theory of racial difference in Southern Africa. The desire to explore racial difference emerged from the typological method which lay at the heart of physical anthropology and which encouraged a belief in the existence of ideal categories. According to Dubow (1995: 114), this typological impulse was then overlaid by binary-based notions of superiority and inferiority, progress, and degeneration.

Of particular interest in Dubow's (1995: 84) work are the ways in which scholars of the time attempted to develop racial ideas to suit political ends without contradicting scientific evidence. For example, the Hamitic myth - used to justify the stigmatisation of Africans as the descendants of Noah's cursed son Ham - endured because of its capacity to adapt "in order to take account of changing ideological demands." (Dubow, 1995: 84). Through reinterpreting the Bible, many authorities declared that only Canaan-son-of-Ham had been cursed. Thus, the Egyptians (with their impressive civilisation) re-emerged as the uncursed progeny of Ham by way of his other son, Mizraim. This reinterpretation justified a belief that "Caucasian Egyptians" (Dubow, 1995: 84) were unrelated and superior to the "lowly" Negro (Dubow, 1995: 84). The history of Africa, according to this 'science', became one of tracing the superior Caucasian influence through the Sub-Saharan African population.

Dubow (1995: 285) also highlights how scientific racism became an important justification for social ordering as South Africa began to industrialise. The impact of rapid industrialisation on predominantly agrarian societies was profound and brought with it the characteristic problems and anxieties associated with modernity; proletarianism, mass poverty, crime, disease, and social breakdown. According to Dubow (1995), the concerns of racial science spoke directly to these anxieties; "its findings helped to rationalize social strictures against racial and cultural inter-mixture, and its warnings of pollution, defilement and degeneration served as powerful justifications of the need for statutory segregation along lines of color" (285). In this way, racial science helped to facilitate the realisation and ideological maintenance of White power and authority.

However, apartheid continued to exist long after scientific theories that justified White superiority were debunked. Dubow (1995: 288) argues that the advent of the Second World War and the revelations about the Nazi use of eugenics which followed it, marked a dramatic shift in scientific attitudes to the force of heredity. At this time, there was a remarkable mid-century transformation in the understanding of the relationship between biology and society. For example, the 1950s UNESCO publication entitled The Race Question states that "it is impossible to demonstrate that there exist between "races" differences of intelligence and temperament other than those produced by cultural environment" (3).

The gradual unpicking of racial science that ran parallel to the gradual reinforcement of apartheid segregation throughout the second half of the Twentieth Century challenges the assumption that scientific beliefs about race shaped racially discriminatory policy. Indeed, as Gilbert (2019: 372) has argued, apartheid logic did not rely on scientific racism. For example, many apartheid-era history textbooks used the language of 'race' to explain Nazi actions in a way that recognised no relationship to apartheid's anti-black racism. Gilbert (2019: 371) goes on to say that although race was the key organising principle for all areas of life in apartheid South Africa, race was not conceptualised scientifically. She quotes the sociologist Deborah Posel (2001), who argues that apartheid ideologues "eschewed a science of race, explicitly recognising race as a construct with cultural, social and economic dimensions" (53).

It would therefore be a mistake to simply equate the racism of apartheid with the racisms that had existed prior to apartheid; different discriminatory logics were used to justify similar racial hierarchies. Dubow, for example, noted that, "Those who until very recently took black incapacity for granted, and designed social policies to reflect that 'fact', now speak smoothly of 'underprivileged communities' and 'educational disadvantage'." (1995: 291). If 'flawed' scientific knowledge is not the cause of racism, then 'correct' scientific knowledge will not be the solution to racism.

Conclusion

We have argued that the concept of race should be taught as a 'construct' and not a 'myth' in South Africa. The current evolutionary approach to teaching about race in Grade 9 History poses two serious challenges. The first is that evolutionary theories are highly contested by many South Africans and the second, is that most history teachers are not scientifically trained and therefore, ill-equipped to draw connections between race and evolution.

Given these constraints, the association created between evolutionary theories and racial theories can result in dangerous misunderstandings. As we have demonstrated both from our own observations and a review of the literature, students are at risk of concluding:

a) that race does not exist and therefore, concerns about structural racism are unjustified;

b) that evolution is a false theory that offends their religious beliefs and identities as human; or c) that racial hierarchies exist because evolution is evidence of the underdevelopment of Black people, or the purity of Black people. Ironically, these misunderstandings are in direct opposition to the learning objectives established by CAPS.

In contrast, a focus on the shifting historical construction of racial ideas is more appropriate for the history classroom, and would reflect international best practice. Such an approach would emphasise the ways in which ideas surrounding race have changed over place and time; how ideas about race and the science that has supported those ideas, have responded to the needs and interests of powerful groups; and, how people can both believe that race is a 'myth' while also engaging in violently racist behaviour.

South Africa is currently undergoing a review of its history curriculum which offers opportunities to rethink the way we teach fundamental concepts. The historiography we have discussed represents only a fraction of the research that has been undertaken on the history of the idea of race in South Africa. However, our purpose in presenting some of these arguments has been to demonstrate that this historical research exists, and that it could be used to inform an approach to teaching the concept of race to Grade 9 students.

References

Apps, K 2021. Inventing race? Year 8 use early modern primary sources to investigate the complex origins of racial thinking in the past. Teaching History, 183:8-19. [ Links ]

Abrie, AL 2010. Student teachers' attitudes towards and willingness to teach evolution in a changing South African environment. Journal of Biological Education, 44(3):102-107. https://doi.org/10.1080/00219266.2010.9656205 [ Links ]

African National Congress. 29th June 2005. 'The National Question'. 2nd National General Council. [ Links ]

Baird, RP 2021. The invention of whiteness: The long history of a dangerous idea. The Guardian. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/news/2021/apr/20/the-invention-of-whiteness-long-history-dangerous-idea Accessed on 20th April 2023. [ Links ]

Bottaro J, Cohen S, Dilley E, Duffett D, & Visser, P 2013. Oxford successful social sciences Grade 9 LB (CAPS). Oxford University Press Southern Africa. [ Links ]

Conradie, MS 2016. Critical race theory and the question of safety in dialogues on race. Acta Theologica, 36(1): 5-26. [ Links ]

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa [South Africa], 10 December 1996, available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b5de4.html [accessed 24 July 2023] [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education (DBE). 2011a. Curriculum and assessment policy statement Grades 7-9: History. Pretoria: Department of Basic Education. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education (DBE). 2011b. Curriculum and assessment policy statement Grades 10-12: History. Pretoria: Department of Basic Education. [ Links ]

Diamond, J 1991. The third chimpanzee: The evolution and future of the human animal. Harper Perennial. [ Links ]

Dryden-Peterson, S., & Robinson, N. (2023). Time, source, and responsibility: understanding changing uses ofthe past in 'post-conflict' South African history teaching, 1998 and 2019. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 1-19. [ Links ]

Du Bois, WEB 1920. "The souls of white folk." In: WEB Du Bois. Darkwater: Voices from within the veil. New York: Washington Square Press. [ Links ]

Du Bois, WEB 1940. Dusk of dawn: An essay toward an autobiography of a race concept: The Oxford WEB Du Bois, Volume 8. Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Dubow, S 1995. Scientific racism in modern South Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Earle, Keats, Edwards, Sauerman, Roberts & Gordon 2013. Social Sciences Today Grade 9 Learner's Book. Cape Town: Maskew Miller Longman. [ Links ]

Facing History and Ourselves 2018. The concept of race. Available at https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/concept-race Accessed on 20th April 2023. [ Links ]

Jardine, Monteith, Versfeld, Winearls 2013. Grade 9 Learner's Book Social Sciences. Johannesburg: Vivlia. [ Links ]

Gilbert, S 2019. Nazism and racism in South African textbooks. In: S Gilbert & A Alba (eds.). Holocaust memory and racism in the postwar world. Wayne State University Press. 350-385 [ Links ]

Kauffman, M 2017. Black tudors: the untold story. London: Oneworld. [ Links ]

Kennett R, Thorne S, Barma S, Allen T, Durbin E, Hibbert D, Patel Z, Quinn ME, Stevenson M, Stewart F, & Yasmin, S 2023. A new focus on ...The British Empire, c.1500-present for KS3 History. London: Hodder. [ Links ]

Mpeta M, De Villiers JJR, & Fraser, WJ 2014. Secondary school learners' response to the teaching of evolution in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Journal of Biological Education, 49(2):150-164. [ Links ]

Pandor, N 2002. Science, evolution, religion and education - creating opportunities for learning in South African schools. In: W James & L Wilson (eds.). The architect and the scaffold: Evolution and education in South Africa, 66-64. [ Links ]

Parle, J & Waetjen, T 2005. Teaching African history in South Africa post-colonial realities between evolution and religion. Africa Spectrum, 40(3):521-534. [ Links ]

Posel, D 2001. What's in a name? Racial categorisations under apartheid and their afterlife. Transformation, 47:50-74. [ Links ]

Robinson, N 2021. "Developing historical consciousness for social cohesion: How South African students learn to construct the relationship between past and present. In: M Keynes, HA Elmersiö, D Lindmark & B Norlin (eds.). Historical justice and history education, 341-63. Cham: Springer International Publishing. [ Links ]

Robinson (2021), "Learning from the past: The role of emotion in deflecting conversations about privilege and power in South African schools". In: Intentions, Power, and Accidents; Shifting the critique of Global Citizenship Education (GCE) to an emic perspective on education for global citizenship. Tertium Comparationis. Jahrgang 26 Ausgabe 2, Seiten: 116-121 [ Links ]

Sue, DW 2013. Race talk: The psychology of racial dialogues. American Psychologist, 68(8):663-672. [ Links ]

Sutherland, C; & L'Abbé, EN 2019. Human evolution in the South African school curriculum. South African Journal of Science. 115(7/8):1-7. [ Links ]

Suttner, R 2012. Understanding non-racialism as an emancipatory concept in South Africa. Theoria: A Journal of Social and Political Theory, 59(130):22--41. [ Links ]

Vincent, L 2008. The limitations of inter-racial contact: Stories from young South Africa. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 31(8):1426-1451. [ Links ]

UNESCO. 1950. The race question. UNESCO and its programme. Paris: UNESCO 3 [31]. [ Links ]

1 See Statutes, 1996: section 1(b), where it is described as one of the values on which the state is founded.

2 It is worth noting, however, that the influence of these new learning resources on students' beliefs surrounding race has not been explored.