Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Yesterday and Today

On-line version ISSN 2309-9003

Print version ISSN 2223-0386

Y&T n.28 Vanderbijlpark Dec. 2022

BOOK REVIEWS

Sinenhlanhla Ndaba

University of KwaZulu-Natal. 211558037@stu.ukzn.ac.za

Author:Johan Raath

Publisher: Delta Books

ISBN 978-1-92824-824-8

ISBN 978-1-92824-825-5 (e-book)

This book details the experiences of Johan Raath, a former Special Forces operator. He offers an insider's view on the training he and other young soldiers received in the mid-1980s, which is quite rare. He describes the phases of selection and training by drawing on the reminiscences of his fellow Recces. He also offers valuable insights into what constitutes a successful operator. The training cycle courses have been designed to show the range and standard of Special Forces training, including handling weapons, bushcraft, survival mechanisms, parachuting, demolitions, urban warfare, and seaborne and riverine operations. Eventually, Raath and his colleagues experienced some level of development when their training culminated in an operation in southern Angola, where the young Recces saw action for the first time. Much of Raath's lived experiences forms part of present-day Special Forces training. In light of the brief background, this book demonstrates why these soldiers are a breed apart. It is important to note that the South African Special Forces was established in the early 1970s. It is currently considered a prestigious and vital South African National Defence Force unit. Selection and training doctrines were initially based on those of the British Special Air Service, with some influence from the French Special Forces, particularly on the combat and diving and seaborne operations side. Air capabilities were drawn from the highly esteemed 1 Parachute Battalion, based in Bloemfontein in the central highlands of South Africa. It was not long before Special Forces operators were referred to as 'Recces'- an abbreviation for Reconnaissance Commando.

The Recces operators got involved in the most challenging operations in Angola, Rhodesia (Present-day Zimbabwe), Mozambique, and other sub-equatorial African countries. Angola and Mozambique attained political independence from Portugal in 1975, and communist governments were installed in both countries. The National Party Government in South Africa perceived these communist African states as threatening white minority rule. The United States of America encouraged South Africa to reject communism outright, given its fight against the spread of communism throughout the world, which was at the height of the Cold War between the Soviet Union (Russia) and the United States of America. South West Africa faced insurgency challenges in South West Africa (present-day Namibia) by the South West Africa People's Organisation (Swapo). It is important to note that at the time, South West Africa was governed by South Africa as a protectorate. The National Party had to deal with the threat posed by Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), the armed military wing of the African National Congress (ANC), and from the Azanian People's Liberation Army (APLA), the armed military wing of the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC).

These groups were insurgents or terrorists/freedom fighters fighting the Apartheid regime first for South West Africa's independence and second for South Africa's democratization. The first South African Defence Force soldier to be killed in action in March 1974 in Angola was Lieutenant Fred Zeelie. He was a Recce operator from I Reconnaissance Commando. The Recce was very busy from 1975 onwards, immediately after Angola and Mozambique attained political autonomy with a backup from the Soviet Union and its satellites. Meanwhile, the white minority regime in Rhodesia faced an onslaught from the Liberation movements. When Rhodesia gained independence from the 1970s up until 1980. The Recces often worked with the elite Rhodesian SAS on operations in Rhodesia, Zambia, and Mozambique where the insurgents had training camps and from where they launched attacks against the Rhodesian security forces. Special Forces from South Africa and Rhodesia were militarily capacitated, hardened bush fighters with a wide variety of skills and specialised tactics derived from operations against numerically more significant enemy forces. In 1980, the old security forces of Rhodesia were discontinued, and a number of SAS, Selous Scouts, and Rhodesian Light Infantry (RLI) operators joined the South African Reconnaissance Commandos. The amalgamation of the Recces with these Rhodesian special operations formations created one of the finest Special Forces organisations the world has ever seen. There were three South African Special Forces units by the late 1970s, namely: 1 Reconnaissance Regiment (Durban), 4 Reconnaissance Regiment (Langebaan), and 5 Reconnaissance Regiment (Phalaborwa). The Special Forces HQ was located in Pretoria. All the operators were schooled in bush warfare, parachute deployments, demolitions, basic seaborne operations, and urban warfare, and each unit specialised in certain kinds of deployment. 1 Recce became experts in urban warfare, 4 Recce in seaborne operations, attack diving, and underwater demolitions, and 5 Recce were masters of larger-scale bush warfare operations, often expedited through fast strikes delivered by light armoured vehicles. Military or police conscription for all white males between 17 and 65 became compulsory from 1976. Initially this duty was performed over nine months. In the early 1990s, military conscription for white males was reduced to one year after Namibia attained independence and the ANC and other political organisations were unbanned. Compulsory military conscription in South Africa was finally abolished in August 1993.

The author provides incisive accounts on his early life which informed his interest in the title of the book. He was born in 1968 in the city of Bloemfontein, in the Free State province. He comes from a modest middle-class family. His father was a teacher and his mother was an administrative secretary at the local municipality. Both his parents grew up on farms in the Free State. His entire family comes from a community of farmers. Raath showed interest in military matters from a young age, including toy guns and real firearms. One of his uncles afforded him an opportunity to experience farm life in the mountainous eastern Free State during school holidays. The uncle taught him how to use a rifle and hunt small animals such as rabbits, dassies (rock rabbits), meerkats, and various birds. Raath made significant progress for example; from a 22 long rifle to a shotgun and later to a larger calibres, which were used to hunt various species of buck (Antelope). He eventually excelled at shooting. Raath's father taught him fishing which he enjoyed very much. He learned horse riding and loved outdoor life in the veld. The author soon realised that all the skills he was taught were actually in his DNA, as they were meant for the Boers who trekked from the Cape into the hinterlands during the 19th century.

Raath's father taught history at high school and was particularly interested in the Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902, as well as its battle sites around the country, which exerted a profound influence on Raath to pursue his military interests to a large extent. Furthermore, he enjoyed narratives on military service, border battles between South West Africa and Angola. Here the South African Defence Force was also engaged in battles against Swapo guerrillas and the People's Armed Forces of Liberation of Angola (Fapla), the armed forces of Angola's communist government. Tales and rumours about secretive Recces and outstanding group of combat soldiers they were. The author developed an interest in becoming a Reece and took part in the cadet camps that young men were encouraged to experience during the winter holiday break. At the age of 16, Raath was ready to actualise his dream of becoming a soldier. He also desired to become a Special Force operator. He was not interested in school. Rugby, cricket, parties, girls and a regular bar fight, were the subjects Raath excelled in. The latter caused him serious injuries that compelled him to undergo facial reconstruction surgery. The consequences thereof imposed some limitations on his academic and social life. He missed school for a couple of months and could no longer play rugby. When the call-up papers arrived, they clearly stipulated the criteria to be met by recruits who wished to join Special Forces. Raath could not meet some of the criteria. Communicating in English was a major challenge given his background as a Dutchman coming from the Free State. Eventually, he was sent off to perform military duties at the age of 17.

The author has been able to detail his lived experiences and perspectives on South African Special Forces coherently through fourteen chapters, which speak to the book's title. In the first chapter, he highlights the most crucial aspects of his journey of discovery that he willingly undertook, hence the crux as a sub-title. The second chapter details the basics of the Special Force and its experiences. Chapter three deals with the orientation of the Special Forces, including induction programmes designed to educate them on the ideals of military engagements. In the fourth chapter, the author explains the selection criteria and standard procedures in-depth. The primary aim was to ensure that recruits are were for purpose. Chapter five covers the role of individuals within the Special Forces Units. In chapter six, the focus is on Seaborne and Water Orientation. The aim was to equip Special Forces with the requisite skills, including diving.

Chapter seven discusses the military strategies that help identify the enemy. In chapter eight, the author delves deeper into the components of the Parachute Course and the extent to which it meets expectations. In chapter nine, Raath provides a detailed explanation on how Aof Operations were conducted. Chapter ten deals with Demolitions and Mine Warfare. In chapter eleven, the author highlights Bushcraft, Tracking, and survival as part of the narrative on the country's Special Forces. In chapter twelve, the Forces are taught minor tactics, guerrilla and unconventional Warfare. Chapter thirteen deals specifically with Urban Warfare. In the book's last chapter (Chapter fourteen), Raath explores the avenues of life beyond the Recce cycle.

In conclusion, Raath's book is a carefully thought out piece of academic writing. It captures the essence of the title so well. Chapters have been chronologically organised, which makes it a lot easier for the reader to grasp the gist of the entire book. The language used has been simplified well for the benefit of the reading audience. The literary style is good. The use of photographs as a visual representation of episodes covered in the book is commendable. Overall, the book is quite an exciting read.

My Pretoria: An Architectural and Cultural

Raita Steyn

University of Pretoria. raita.steyn@up.ac.za

Odyssey

Author: Eftychios Eftychis

Publisher: Dream Africa

ISBN: 987-0-9947240-8-3

My Pretoria, an Architectural and Cultural Odyssey is a coffee table book, a collector's limited edition unlocking some of Pretoria's (Tshwane) (the administrative capital of South Africa) magnificent old edifices such as churches, mosques, temples, as well as educational and residential buildings etc. in the form of drawings. The book launch took place at the Hellenic Community Hall in Pretoria in July 2022. At the opening event, there was also an exhibition of some of the author's original drawings.

All the fifty-six illustrations of heritage buildings were created between 1979 and 1980 by the author, Eftychios Eftychis, a well-established architect and artist in Pretoria. Though the images were drawn more than four decades ago, the selected buildings exemplify their well-maintenance and preservation as captured at that time. Yet at present-day, due to neglect many of the structures are in decline, and, as the author states, "require urgent renovation" (p. xvii).

This special edition is dedicated to the author's wife, Dimitra (Loula), whom he describes as "a driving force in his life" (p. xii). The book has a dual aim: firstly, to artistically contribute to preserving visually the architectural creations of Pretoria, and secondly to evoke sentiments of nostalgia to those who have been living under the shade of the illustrated edifices and form part of the city's history.

The title of this volume, My Pretoria, an Architectural and Cultural Odyssey is well-chosen. Eftychios Eftychis, of Greek Cypriot origin, was born and raised in Pretoria, hence his closeness to his South African hometown. By defining his book as "... an Architectural and Cultural Odyssey", Eftychis expresses eloquently his blended South African-Hellenic cultural identity.

The term 'Odyssey' in the title, instantly caught my attention as it resonated Constantine Cavafy's poem, Ithaki, which defines the joy of one's journey to be found not in reaching their destination but in the course of the journey itself:

"Το φθάσιμον εκεί είν' ο προορισμός σου, Αλλά μη βιάζεις το ταξείδι διόλου..."

(Arriving there is your aim...But don't rush the journey at all...) (Ithaki),

My Pretoria, an Architectural and Cultural Odyssey takes the reader on an artistic journey which starts with the author's early life, sails with us through his student life, early career, his family life. Sharing his travel adventures, we arrive at the final section of the book, realising that viewing the artworks - is what we were 'destined for', i.e. to enjoy the journey without haste, aesthetically, scholarly and sentimentally.

As for the layout and design of "My Pretoria... ", realised by the author's son, Creon Eftychis, they are visually appealing, as they maintain a balance between a voguish styled journal and a classic publication. The typography and layout are professionally designed with a colour combination of black and white, highlighted by purple to strengthen the visual language of the book. The purple ink symbolises the beautiful Jacaranda trees of Pretoria whilst the black and white is a reminder of the political struggle between black and white in our multi-cultural, multi-lingual country. Apart from representing the beautiful Jacaranda trees which were introduced to Pretoria in the early 1800s, mostly for aesthetic purposes, the purple colour also complements the author's eccentric clothing, i.e., his "favourite Carnaby Street outfit of yellow bellbottoms" (p. 18), creating thus an imaginary contrast in visual colour.

The book is introduced by four highly distinguished specialists, Emeritus Prof Dr Dieter Holm Emeritus Head of the Department of Architecture, University of Pretoria, Mr Leon Kok, political and financial reporter, news commentator, editor-in-chief and parliamentary correspondent, Mr Han Peters, Ambassador of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in South Africa, and by the Very Reverend Archimandrite Fr. Michael Visvinis, Dean of the Holy Orthodox Cathedral of the Annunciation of the Theotokos (Mother of God), Brooklyn, Pretoria. The opening section (pp. x-xxi) ends with the author's own voice, giving the reader a deeper understanding of the why and how he decided to transform his architectural sketches into a long-lasting publication, preserving them in his own way as part of an "Africana" shared cultural heritage, which now belongs to a diverse country. These sketches depict structures built between 1876 and 1933, the time when "Dutch and British colonisation had a huge impact on the architecture of the edifices in the urban landscape..." (p. xviii).

The opening of the book is followed by two main sections, My life in Pretoria (pp. 1-27) and The Built Environment (pp. 29-139) which are further divided into sub-headings, starting from: Early Life; Back to My Roots; World of Learning and Work; Family, House, Home; Adventure and Creativity.

In this section, the author introduces us to his Greek Cypriot family, starting with his life's foundation years. Eftychis' father Euripides, immigrated to South Africa in 1934 but returned to Cyprus to marry the author's mother, Katina in 1946. They settled in Pretoria and as so many Greek emigrants at the time, his father too, opened his first café, the Union Café. The business later moved to Brooklyn where his father established the Brooklyn Terminus Café. This café was a hub frequented by high VIPs which included, cabinet ministers, ambassadors, doctors, lawyers. The author shares interesting facts and happenings relating to the South African social-political conditions of the time. For instance, while in exile King George II of Greece and his brother, Crown Prince Paul with his wife, Princess Frederica with the rest of the family, came to settle for a while in South Africa during the Second World War (Rand Daily Mail, 1941, p. 7; Fourie, 2013, Mantzaris, 1978, pp. 52-53). As they were touring the country, Eftychis's father, as one of the Pretoria Greek community members, was invited to attend the welcoming ceremony of the exiled royal family, hosted by the Prime Minister and General, Jan Smuts (p. 5).

It was in 1942, here in South Africa (Cape Town), where the youngest child of Crown Prince Paul and Princess Frederica was born. With General Smuts as her godfather, the young princess was symbolically named Irene (in Greek Peace), a ceremony that took on a most important role in the Greek Orthodox socio-religious events. As a matter of interest, in 1889, businessman, Alois Hugo Nellmapius bought two thirds of the Doornkloof farm (outside Pretoria) and renamed it 'Irene Estate' after his own daughter, Irene. In 1908, General Jan Smuts bought one third of the original Doornkloof/Irene farm, making his permanent home for more than 40 years. The house, declared a national monument in 1960, today is known as the Smuts House Museum. After his death, General Smuts' ashes were scattered on Smuts Koppie near Doornkloof (Heathcote, 1999, p. 266).

Concerning the social-political tensions in South Africa around 1953, the year when Eftychis was a boy of merely six years, one of their customers, the Russian ambassador, came to bid them farewell, because the South African Government had closed down the Russian Embassy (p. 4). All these socio-cultural events are relevant because, pedagogically both directly and indirectly through narratives, have played a significant role in shaping the young Eftychis's personality and his socio-cultural value system.

The author had identity insecurities and experienced cultural clashes just as many immigrants' children do. His insecurities started at an early age at school when his fellow mates made stereotypical remarks about his Greek family's roots, which linked to their business and daily life made the author wonder about his identity. Was he a Greek, a South African or rather neither, but just an "uitlander", as many had labelled him (p. 6). This part of the author's narrative is extremely relevant regarding the childhood of those with parents who had emigrated especially from Southern Europe countries such as Greece, Portugal, and Italy, as they tried to adapt in a highly segmented South African socio-cultural structure. Luckily, today South Africa as a most diverse country, accepts and fosters multicultural communities.

To make things worse, on 10 September 1966, ten days before Eftychis's nineteenth birthday, Prime Minister Hendrick Verwoerd, the father ofApartheid was stabbed to death by the Greek-Mozambican, Dimitri Tsafendas. Eftychis remembers vividly how "all café owners were forced to close their shops for fear of retaliation and damage to the property" (p. 6). It was not an unusual happening to have riots in South Africa, in fact, during 1915 to 1917, violent riots, instigated by the Boers and the British, broke out against Greek shop businesses, because Greece remained neutral during World War I (Chrysopoulos, 2022).

Regarding his escape from the world of reality through his art, Eftychis had the privilege of being taught both art theory and practice by the renowned South African artists, Walter Battiss and Larry Scully during his high school years, and of course not forgetting his Italian teacher, Aunty Delia who had been his private art teacher for not less than ten years. Battiss's vibrant use of watercolours and his love for Greece and islands, as well as Scully's abstract approach to art, succeeded to motivate Eftychis to becoming a better creative thinker and inventive artist and architect (p. 7). Eftychis's designs reflect his ancient Greek, Danish and Finnish inspirations as well as his art teachers' stylistic influence in terms of applying vibrant colours, scale and harmony.

With reference to the influences on his early life and later his married and family life, while reading through the sections Back to My Roots; World of Learning and Work; Family, House, Home; Adventure and Creativity (pp. 9-27), it is evident that Eftychis developed more strength to mature his artistic talent. He wanted to show that one's heritage is important on the journey from the past to the future, as one's past also influences how one perceives the world around them. Through his humbleness, endurance, and strength, I believe, the author became more empathetic and aware of the importance of the environment in everyone's life.

Moving to the second section, The Built Environment (pp. 29-139), we find a well-balanced sequence of drawings of heritage buildings in Pretoria, purposefully divided into categories of representative types rather than chronologically, i.e., Government Buildings, Commercial Buildings, Places of Worship, Places of Learning, Residential Buildings and ends with Parks and Recreation Buildings. This section - the emphasis being on the drawings -opens up with two maps, one of Pretoria Central Business District and the other of Greater Pretoria, to give the reader a better understanding of the structures' placement and how the buildings link with one another, followed by many heritage landmarks.

Each panoramic page has a drawing accompanied by a short, informative text about the heritage site, highlighting the different styles of architecture used to create porticos and façades, cupolas and turrets, galvanised roofs, pediments, pillars and columns, and mouldings and finials, which were created in the past by different regimes. Furthermore, the author provides the reader with factual information by adding some interesting historical points on events linked to a specific building (e.g. seat of government, museum, train station etc.)

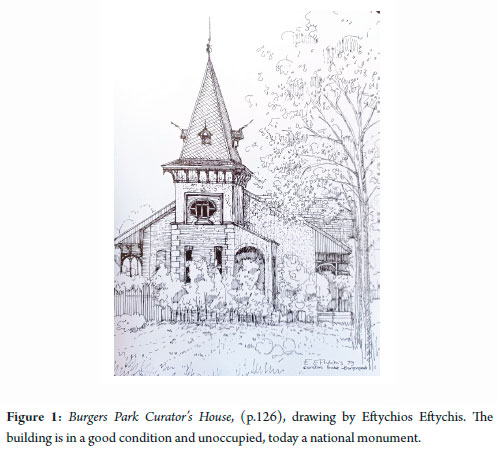

If I had to select one as my favourite drawing, it would be the Burgers Park Curator's House in Jacob Maré Street (now Jeff Masemola Street) (Figure 1) (p. 127), designed after a Victorian red brick façade with typical tiled roofs by Van der Ben, and built by Simon, in 1892. This heritage building is decorated with some curvy-linear Art Nouveau features which include fish-scale patterned metal roof, hat-shaped turrets, ornate wooded brackets and oval shaped windows makes it one ofmy favourite buildings (p. 126).

Paging through the visually rich artworks of the Places of Worship (pp. 78-95) makes one realise that South Africa is indeed home to multi-diverse groups of people, a fact that defines the country as a multi-coloured mosaic of multi-religious and multi-cultural particles. The impression is overwhelming as one looks at the meticulously and detailed hand-drawn sketches of Churches of Protestant denominations, a Roman Cathedral, the Queen Street Mosque and the Old Synagogue, built by various communities, demonstrating thus collective commitment towards their second country and freedom of cultural identity. Yet, in my opinion, this collection would have been more complete had the author added a depiction of the Mariamman Temple as it is one of the architectural jewels of Pretoria. Located in the historical district of Marabastad, the Mariamman Temple was built for the Tamil Community in 1928. Today, compared to the rest of the building sites, it is someway isolated from the inner-city and therefore seems somehow deserted.

The historic artistic narration, and to many readers also nostalgic, continuous as the author guides us from Places of Worship, to Places of Learning (pp. 97-105), with buildings that have hosted and educated thousands of young South Africans towards responsible citizenship. The section is followed by the Residential Buildings after which the author concludes his guidance with Parks and Recreation Buildings (pp.135-139). At this point, the reader can assess the value of Pretoria's infrastructure through which architectural art has been trusted to successfully combine three most vital elements in a human life: a. the physical, in terms of safety and permanence; b. the spiritual, in terms of inspiration and faith; and c. the intellectual, in terms of a human value system, developed since childhood at the proper educational environment.

There is a wide range of sources substantiating the given information and for further research on the architectural history of Pretoria. The book ends with the final section which presents, in alphabetical order, a scholarly detailed index of names, places and other information associated with each relevant topic.

My Pretoria, an Architectural and Cultural Odyssey will appeal to everyone with an interest in the heritage buildings beyond Pretoria's outskirts in other South African cities too. It is aesthetically a pleasing volume that enriches the collection of books about Pretoria, firstly as a carrier city of an important heritage legacy, and secondly by setting the city as a socio-political centre globally significant where human values have prevailed and upon which the future of the new, rainbow nation has been designed, built and publicly manifested by any new political leader.

References

Chrysopoulos, P. 2022. The Turbulent Story of Greeks in South Africa. Available at: https://greekreporter.com/2022/06/07/the-turbulent-story-of-greeks-in-south-africa/ . Accessed on 28 October 2022. [ Links ]

Fourie, J. (2013). Available at: https://www.johanfourie.com/2013/07/24/frederica-of-hanover/. Accessed on 29 October 2022. [ Links ]

Heathcote, T.A., 1999. The British Field Marshals 1736-1997. Leo Cooper: UK. ISBN 0-85052-696-5. [ Links ]

Mantzaris, E.A. 1978. The Greeks in South Africa. The social structure and the process of assimilation of the Greek community in South Africa. Thesis. University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

Savvides, G.P. 1963 (ed.). K. LL. Kafiâpn LJoi^uara, vol. I (1896-1918). Ikaros, Athens. Rand Daily Mail. 1941. "King of Greece coming to S.A this week". 7 July, p. 7. [ Links ]

The Conversation. 2020. The story of a remarkable Hindu temple in Pretoria's inner city. March 22, 2020. Available at: https://theconversation.com/the-story-of-a-remarkable-hindu-temple-in-pretorias-inner-city-133942. Accessed on 31 October 2022. [ Links ]

The Smuts House Museum: Home of General Jan Smuts from 1910-1950). Available at: http://www.smutshouse.co.za/ . Accessed on 29 October 2022. [ Links ]

Institutional Curiosity

Yolandi Woest

University of Pretoria. yolandi.woest@up.ac.za

Edited by: Mary Crewe

Publisher: ESI Press

ISBN: 978-0-620-99230-5 (print)

ISBN: 978-0-620-99231-2 (e-book)

Institutional Culture is a collaborative endeavour between the University of Pretoria and Emerging Scholars Initiative Press (ESI Press). This book includes the writings of fourteen UP academics in different genres such as opinion pieces, thoughts, and reflections. This collection had at its aim illustrating the reimagination of the University of Pretoria and how it may look in the future from the perspective of UP academics. Two questions were the drivers of these writings: How do we think UP looks now? and, How do we think UP should or will look in the future? First, this work is exceptionally significant because all authors belong to the institution about which they wrote. Subsequently, the authors provide the reader with an insider perspective, (Lindbeck, & Snower 2001). These authors are well-positioned in that they are writing about the institution from within the institution. Second, all authors have some institution knowledge (Corbett, Grube, Lovell, & Scott, R., 2020), which further proved to be valuable and is evident in all the writing pieces. These are authors who know the institution and this fact enhances the credibility and significance of this work.

Last, this work is timely. During the COVID-19 pandemic the entire educational arena came to a complete standstill for a brief moment in time. For a moment, there was a worldwide pause in education before all academic staff frantically started developing emergency plans to navigate their professional identities, professional contexts and teaching practices to navigate the unfamiliar and threatening circumstances. This 'pause' encapsulated more than the rethinking of teaching and learning practices to include a deep reflection on the nature of tertiary institutions in its entirety. Globally, much has been written about the changing landscape of tertiary institutions, (Burki, 2020; García-Morales, Garrido-Moreno, Martín-Rojas, 2021; Mhlanga & Moloi, 2020; Paudel, 2021). In Institutional Curiosity, the publication addresses in innovative ways with a fresh approach on how policy can be used to generate change, debate, and institutional curiosity, rather than being perceived as a form of control and coercion.

The title, Institutional Culture, is concise and well-selected. It summarises the gist of the entire book in an apt phrase. The cover design by Alastair Crewe complements the content in that the image of the feather pen in an 'old' inkpot links with the idea of personal and authentic writing such as personal thoughts and opinion pieces.

The book is divided into eleven sections. Each new piece of writing is indicated with a clear heading followed by the identity of the author(s). I thought it especially fitting that the book was not divided into chapters which might be an alternative divisional possibility. The fact that the division is merely indicated by the title of the consecutive writing piece, creates the idea of all writings being equally significant and strengthens the idea of 'personal' writing.

The book is introduced by Mary Crewe, the former Director of the Centre for Sexualities, AIDS, and Gender (CSA&G) at the University of Pretoria. In the Foreword, she introduces the book with a powerful metaphor about pearl fishing. She compares the upsetting of the natural sedimentation of the academic institution to the way in which pearl fishing 'upsets' the ocean floor. The foreword is written powerfully, and the author succeeds in setting the scene for what follows: the disturbance of layers of history, several engagements in topics such as change, continuity, knowledge, and excellence. Furthermore, she unpacks the rationale for the title of the book: to challenge the term of 'institutional culture' by extending this to 'institutional curiosity' and by so doing, changing the narrative. The author clarifies the way in which the publication reflects how the University could be re-envisioned, and address questions raised by institutional culture. According to Mary Crewe, 'one way to think about institutional culture and all that arises from it is to change the narrative to institutional curiosity.

Authors in this work dealt with several contemporary and pressing issues concerning reimagining the future of UP. All authors agree that the landscape in higher education is changing, and that it should be ensured that we shape the landscape, rather than being left behind. The views ofauthors are critical ofthe previous regime and how the inequalities were exacerbated by the pandemic (among other factors) but also optimistic. Professor Siona O'Connell commented on the effects of prevailing inequalities and social engineering "that characterised the apartheid system" (p.14), despite nearly three decades of democracy. She offers practical suggestions for engagement with these issues in an attempt to pave the way towards a better future. It is worth mentioning that although authors engaged in a critical way with certain issues, they are also hopeful. I appreciated the positive tone evident through all the writings and several authors provide helpful suggestions to alleviate some of the fears and concerns they shared.

Authors engaged with UP as learning space from different perspectives. In this book, UP is reimagined as a shifting and dynamic learning space within the broader contextual city of Tshwane and the surrounding community is addressed. Authors showed how the immediate and broader context in which the institution is situated, can be utilised to learn from each other and the surroundings. I found the section on the "city as classroom" (suggested by Profs Stephan De Beer and Jannie Hugo, p. 26) especially insightful. Additionally, the changing nature of this learning space were considered from varying angles with a strong focus on how the pandemic changed the educational landscape of the institution. Authors engaged critically with the advantages of hybrid learning spaces. However, they also highlighted disadvantages such as online-fatigue experienced by students, the lack of opportunities for socialisation and especially how the pre-existing socio-economic gap might be widened to an even larger extent.

Extending UP as learning space, authors also engage with issues regarding this learning space as being a person-centred learning space in the future. They dealt with a range of topics focused on the person within the changing learning space. Matters of family structures, sexual harassment, poverty, the intersectionality of race, class and gender were deeply interrogated in various sections in this work and unpacked from divergent points of view. Exceptionally significant points were brought to light in all the writing pieces, and it would be interesting to view the next volume in this series.

Each writing piece concludes with a reference list and in certain cases, words of acknowledgment. All authors have used a wide range of recent and relevant sources. The book ends with the Index as last section. This section consists of an alphabetical, detailed list of scholarly terminology with correlating page numbers which makes for easy reference by readers.

Institutional Culture is an important collection of opinion pieces, thought and reflections by writers from within the institution, the University of Pretoria. This book is a brave collaborative attempt to unlock the possibilities for the future of this institution in what is expected to be a series of publications surrounding this topic. During the book launch of Institutional Culture, the Vice-Chancellor, Prof Tawana Kupe, described the book as 'pushing the frontlines, intersections and opportunities that arise with institutional curiosity to pave the way for us all in one way or another to be both activists and intellectuals.' The publication includes contributions from Prof Siona O'Connell, Prof Christian WW Pirk, Prof Stephan de Beer and ProfJannie Hugo, Ms Heather A. Thuynsma, Prof Faheema Mahomed-Asmail and Dr Renata Eccles, Prof Cori Wielenga, Dr Aqil Jeenah, Dr Chris Broodryk, Prof David Walwyn, Dr Sameera Ayob-Essop and Prof M. Ruth Mampane, and Prof Nasima M.H. Carrim.

References

Lindbeck, A., Snower, J. 2001. "Insiders versus Outsiders". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 15 (1): 165-188. [ Links ]

Corbett, J., Grube, D., Lovell, H., Scott, R. 2020. "Institutional Memory as Storytelling: How Networked Government Remembers". Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

García-Morales, V.J., Garrido-Moreno, A. and Martín-Rojas, R., 2021. The transformation of higher education after the COVID disruption: Emerging challenges in an online learning scenario. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, p.616059. [ Links ]

Paudel, P., 2021. Online education: Benefits, challenges and strategies during and after COVID-19 in higher education. International Journal on Studies in Education, 3(2), pp.70-85. [ Links ]

Burki, T.K., 2020. COVID-19: consequences for higher education. The Lancet Oncology, 21(6), p.758. [ Links ]

Mhlanga, D. and Moloi, T., 2020. COVID-19 and the digital transformation of education: What are we learning on 4IR in South Africa?. Education sciences, 10(7), p.180. [ Links ]

The Boer War in Colour

Zuzile Ngcobo

University of KwaZulu-Natal. 217030394@stu.ukzn.ac.za

Author: Tinus Le Roux

Publisher: Jonathan Ball Publishers

ISBN: 978-1-77619-203-8

In the opening section of the book, the author highlights the importance of infusing technological revolution in photography, in order to capture the essence of the Anglo-Boer War that broke out in 1899-1902. The war impacted South African society politically, socially and economically. It also changed the political landscape of the country in various respects. The Afrikaners suffered a crushing defeat in the war and were circumstantially obliged to regroup as a nation.

The book presents a pictorial history of the Anglo-Boer War which represents technological and digital realms in modern times. The author contends that since the beginning of the 21st century, there have been developments in the technological and digital spaces. Le Roux's practical application of the technological revolution in photography in this book, is a modern milestone. The title: 'The Boer War in Colour' attracts the reader to explore the unique format of the book. It further triggers an interest in what really sets it apart from previous publications on the Anglo-Boer War. At first glance, the phrase: 'A picture is worth a thousand words', rings true. The overall format of the book is beautiful, it makes the reading thereof a pleasant experience. The effective use of full colour enhances the magnificence of the photographs. The visual images of the war presented in the book, capture the interest of the reader. Furthermore, emotions are evoked and the reader becomes more empathetic through this visual representation of the war. The book stretches beyond the boundaries of literacy and covers a broader spectrum of the reading audience. The people who cannot read can easily grasp the true essence of the war. The participants in the war and how it impacted them was fairly captured through the use of photographs. It sought to provide a balanced version of the war and its features. However, the book does not delve deeper into full scale war and its intricacies. The narrative provided is not extensive enough given the gravity of the war and its impact on South African society. There are no chapters in the book, only a brief overview of some episodes of the war that have been covered. Selected albums that portray visual images of the war reign supreme in the book as opposed to an in-depth account of the war. Extensive coverage of the war coupled with visual images, would have been more welcome. In essence, the author explains in some more detail the selected photographs, rather than a more detailed account of the war. The book covers the conventional phase of the war particularly from October 1899-September 1902. The Afrikaner infiltration into Natal and the Cape Colony, the siege of Ladysmith, Kimberly and Mafikeng. The major battles such as Elandslaagte, Magersfontein and Paardeberg, are some of the aspects of the war that were covered in the book. The author further provides visual images of the campaigns, life in the concentration camps, gunners in action, infantrymen on the march, the burghers, nurses, musicians and prisoners of war.

However, some crucial aspects of the Anglo-Boer War such as the military positions of the British and the Boer armies, the role of Blacks, British Scorched Earth Policy, the role of Emily Hobhouse, the guerrilla tactics of both armies, various places within the country where the battles took place, the crushing defeat suffered by the Boers and the Treaty of Vereeniging which concluded the war, were not covered extensively in the book. A much more detailed narrative on these aspects, coupled with relevant photographs, would have been judicious. Fransjohan Pretorius, South Africa's renowned historian who has written extensively on the Anglo-Boer War, contends that it is terrific to experience the Anglo-Boer War in colour, which represented various episodes endured by its participants. The author provides a brief account of the causes of the war, which is highly contested. Some scholars believe that the war was primarily fought over South Africa's mineral resources, particularly gold on the Witwatersrand. It was more of an imperial war waged by the British on the Boers, seeking to harness the country's mineral resources. The Afrikaners were merely resisting British imperialism.

Le Roux argue that the origins of the war can be traced back to the 19th century and the British occupation of the Dutch Cape Colony in 1806. The issues of governance by the British drove the Afrikaner farmers out of the Cape Colony. They embarked on what was known as the Great Trek and headed to the hinterland literally running away from British control. They were also looking for good farming prospects and better grazing land for their livestock. The Boers were mainly the descendants of the Dutch, German and French settlers. They sought total emancipation from British control and economic prosperity. The author demonstrated the semblance of growth and development of the Boers after leaving the Cape Colony. They managed to assert themselves as an independent nation. Eventually two Boer Republics were established namely: Transvaal and Orange Free State. At first, the British recognized the independence of the Boer Republics, however, such recognition was short-lived. It would have been prudent to highlight the two phases of the Anglo-Boer War and the fundamental differences between them. The first Anglo-Boer War was triggered by the British attempt to annex Transvaal in 1877. It then broke out from 1880-1881. In this phase of the war, the Boers emerged victorious. The British suffered a crushing defeat at the Battle of Majuba Hills at the hands of the Afrikaners. The Transvaal independence was therefore restored. The discovery of gold on the Witwatersrand in 1886, made Transvaal the richest province in the country and the entire Southern Africa. Such economic prosperity attracted migrant workers from a variety of world countries. The spectre of challenge presented by this economic development was an increase in the number of foreign migrants which outnumbered the Boers in the Transvaal who were mostly farmers. The Transvaal Government was left with no option but to impose strict control measures on immigration. Franchise and full South African citizenship were among the conditions laid down by the Government, in order to mitigate the impact of immigration on the country's economy and political stability. Interestingly enough, Le Roux sheds some light on how Transvaal's economic prosperity was manipulated by the imperialists such as Cecil John Rhodes who was prime minister of the Cape Colony at the time, in order to achieve their selfish ends. Rhodes used the Uitlanders question as a pretext for imperial expansion.

He attempted to stage a Coup d' etat in the Transvaal led by his close ally Dr Jameson. The aim was to topple the Transvaal Government. A well-armed group invaded Transvaal from Bechuanaland (Present-day Botswana). However, the Jameson Raid was thwarted by the Boer Commando long before they reached Johannesburg. The Boers in the Transvaal and Orange Free State decided to step up their security. They embarked on a re-armament programme, acquired an arsenal of modern arms mainly from Germany, France and also from Britain. Jameson resigned following the failure of the Raid that he orchestrated and carried out. The Boers were now united by a common goal, which was to rid themselves of British control and occupation of their territories. Under the presidencies of Paul Kruger in the Transvaal and Marthinus Steyn in the Orange Free State, the Boers demanded the withdrawal of the British army from their provinces. They laid down an ultimatum to that effect, which the British Government rejected outright. The Boers were left with no option but to declare war on 11th October 1899.

At the beginning of the war, the British army was at the highest peak of its military preparedness. They had a military advantage over the Boer army. The author does touch on the military strategies of the Boers. The focus was on the elimination of the British garrison towns and the railway lines closer to their borders. The Boer offensive took place on in October and November 1899 on three fronts namely:

1) Natal front which features northern Natal: Newcastle, Ladysmith, Colenso and Escourt.

2) Western front, Cape Colony: Mafikeng, Kimberly and Belmont.

3) Central front, Cape Colony: Colesberg and Stormberg region.

On the Natal front, the Boers achieved some level of victory, however, they lost the first two Battles at Dundee (Talana Hill) and Elandslaagte. The author's coverage of the Battles that took place on these fronts is commendable. It provides the readers with perspectives on both the Boers and British offensives. However, a visual representation of these Battles would have been more welcome. Furthermore, it would have been more interesting for the author to provide a much more detailed account of the Battles that took place on other fronts within the country, coupled with photographs relevant enough to compliment the entire narrative. The format of the book has challenged conventional approaches which accounts for its uniqueness. The author has demonstrated innovation and creativity which help the reader capture the true essence of the Anglo-Boer War and its overall impact on South African society.

The book has successfully represented various episodes of the Anglo-Boer War through the full use of photographs. It responds to modern trends which are technologically driven. Furthermore, it demonstrates the extent to which historiography fits in the digital world. Such innovation will undoubtedly encourage history teachers to explore avenues of technology which will make the teaching and learning of history a pleasant experience. Pictorial versions of history writing have been confined to primary school learners with an understanding that they best suit their cognitive levels. Le Roux's book is challenging this notion. In light of the visual representation of the war, pictorial versions of history cut across all cognitive levels. They help simplify the content and make the entire reading fascinating to the reader.