Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Yesterday and Today

On-line version ISSN 2309-9003

Print version ISSN 2223-0386

Y&T n.28 Vanderbijlpark Dec. 2022

TEACHERS VOICE / HANDS-ON ARTICLES

Teaching for belonging: a course facilitating global pluralism, and dialogue

Marj BrownI; Daniel Otieno OkechII

IUniversity of Cape Town, Online Highs School, Cape Town. South Africa

IIDepartment of Educational Management, Policy and Curriculum Studies, Kenyatta University. Nairobi, Kenya

The Canadian Global Centre for Pluralism and European History NGO Euroclio1recently offered a pilot course for teachers on Teaching for Belonging. The aim of the course, as stated by the organisers, was that "there is widespread recognition that education has an important role to play in building inclusive and equitable societies that are resilient to intolerance, exclusion and hate". The training sought to address challenges teachers face, including the persistence of one-sided historical narratives that can perpetuate group-based conflicts and limit students' ideas of who belongs and who should hold power in their societies, the need for dialogue facilitation training so teachers can create spaces for discussions that explore controversial issues related to diversity and the increase of fear and hate-based narratives around difference that come from the student's often uncritical engagement with social media -thus the need for digital literacy.

Let me first define pluralism: according to the Global Centre for Pluralism, diversity in society is a universal fact and how societies respond to diversity is a choice. Pluralism is a positive response to diversity. Pluralism involves taking decisions and actions as individuals and societies grounded in respect for diversity. Teachingfor belonging encompasses pluralism in the classroom.

I attended the pilot training early this year, and this paper reflects on the course with Dr Daniel Otieno Okech, lecturer at Kenyatta University and one of the course facilitators. As Dr Daniel Otieno Okech states when contextualising the course:

One of the ways in which the discourse around colonialism is being promoted is through virtual exchanges between countries in the global west and those in the south. Decolonisation is about reconstructing the African continent. The continent's history, the way its cultures and civilisations are studied and the understanding of its political economy have been shaped by European thinkers (Chukure, 2016). This one-sided perspective must change through candid discussions. The movement to decolonise education in Kenya started at the end of the 1960s after the country won independence from Britain. Garuba (2015) writes that the "fundamental question of place, perspective and orientation needed to be addressed in any reconceptualisation of the curriculum". Garuba (2015) has alluded that the process of decolonising the curriculum needs to be done contrapuntally. The contrapuntal analysis considers the perspectives of both the colonised and the coloniser, their interwoven histories, and their discursive entanglements - without necessarily harmonising them or attending to one while erasing the other. This means that as we revise the curriculum to incorporate African perspectives, we should not erase the colonial perspective, which also adds value to the curriculum.

"Similarly, one has to look at cross-continental dialogue and exchange of ideas within this framework - the dialogue can facilitate a better understanding of each other, but who creates the forum, and is it equal for everyone? Even language, the most basic starting point, means that not all are on an equal footing".

As a Kenyan, Dr Daniel Otieno Okech's involvement in this discourse has been mainly via participation in several virtual exchange programmes with academic colleagues from Europe and Africa as a trained and UN-certified virtual exchange facilitator. He reflects that

as much as the topic of decolonisation is covered in these programmes, there is a paucity of information derived from the African content that represents the African perspective. The topics of diversity and inclusion are still presented from a Eurocentric/ Americentric perspective.

In the Teaching for Belonging course, I was asked to invite two or maybe three other teachers to join, as this was a pilot. I did invite and get acceptance from three other teachers, but once the course started, they all failed to attend due to teaching commitments or workload. The course was asynchronous for the most part so that one could work through modules in one's own time, and every three weeks or so, there were online meetings set up where one could choose which time zone/time slot suited one best. The modules had deadlines, including commenting on the coursework and each other's responses.

Participants included teachers from Eastern Europe, Western Europe, the USA, Canada, Africa, Russia, South Asia, and South America. Forty-five educators from over 30 countries were selected, the majority of whom were recommended to GCP or who had reached out to express interest. Every participant was recommended because of their commitment to or interest in fostering and advancing equity, diversity and inclusion in their work. GCP anticipated that several participants would drop out throughout the training. In the end, 37 participants completed the training.

Of the 37 participants, 30 were classroom teachers who taught various subjects, from history and social studies to science and drama. The other seven participants included a history museum director, representatives from non-profit education organisations, a teacher trainer and a guidance counsellor. This led to rich debate and discussion as the course required completing modules and activities. Teachers could comment on the application of tools and approaches in their classes and engage in online dialogue with one another. There were also live webinars and debates facilitated as examples of handling conflict and ensuring that all pupils are heard. When attending the course, I could apply some of the tools and frameworks to sections of work, and it was interesting to witness pupils' engagement in difficult and emotive topics. There were some takeaways regarding insights into controversial topics and how important it is to make everyone feel heard. Still, not all opinions are inclusive, and one has to be mindful of how to deal with opinions that seek to divide and perpetuate discrimination or how to deal with a participant who may start to feel threatened by the discussion.

With such tools, it is easier for a teacher to explore controversial topics and facilitate decolonising the curriculum, as it allows for the hidden histories/experiences and voices in the classroom to emerge rather than just the dominant narratives.

As the GCP states

We are living in a historic moment of urgency for pluralism. Societies worldwide are being challenged to address injustice, inequality and exclusion issues. When societies commit to becoming more just, peaceful and prosperous by respecting diversity and addressing systemic inequality, the impacts can be transformational. When the dignity of every individual is recognised, everyone feels they belong. We are all better off for generations to come.2

The course was full of excellent reading material on pluralism, identity and social justice.

At the beginning of the first module, participants were challenged to write down ten things that encapsulate their identity. Then they were asked to shave this down to 4 aspects, and finally two. It was interesting to see how many people chose their religion or nationalism as their core identity, while others chose family member, sister or brother- more familial terms. We then discussed the social identity wheel-which helped us unpack different forms of identity. (Appendix A)

This led to a discussion on how people outside of that identity could be excluded somehow, and we assessed different forms of exclusion in our contexts.

The second module explored how historical narratives influence a person's sense of belonging in the present. We analysed multiple perspectives of a single historical event. There were questions such as:

• In a few sentences, describe a major event from the past in which there was a conflict between two or more groups as it relates to inequality and exclusion, which is part of your history education curriculum.

• Who was presented as a hero, victim, or perpetrator?

• Do you think some groups, perspectives and related events are missing? Which ones?

• How do you think your history education has contributed to present-day ideas of who belongs in your society?

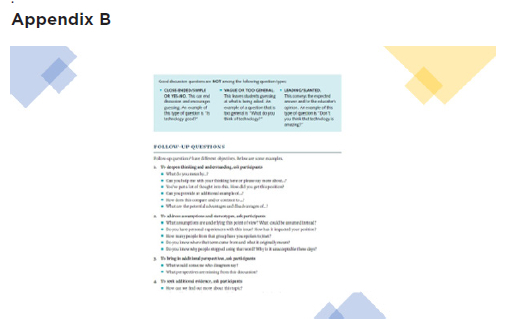

The third module explored the purpose and practice of dialogue, and this flowed into exploring tools for educators to facilitate dialogue. This included designing a "brave space", setting ground rules for dialogue and formulating questions that deepen thinking. The Good questions guide helped teachers distinguish between questions that facilitate open-ended dialogue and those that are closed, slanted, or vague. (See Appendix B)

Digital pluralism and the need to create respectful and inclusive online spaces, teaching learners to recognise how online information may be filtered, monitored or manipulated was also a focus of the course.

Educators and students can take specific actions to connect with different perspectives online. Some of these individual actions include the following:

• While there is an ongoing debate on whether filter bubbles and echo chambers are more or less harmful, there appears to be a consensus that it is worth being aware of them. So, an initial step in responding to echo chambers and filter bubbles is being aware of them.

• Learn about how personalisation works on different sites. Explore which personalisation settings users have control over, especially those that can be turned on or off. Review user ad preferences. If you want to seek wider perspectives or find out what information you would get without personalisation, you can use browsers that don't track your history or conduct your searches using incognito mode.

• Consciously (and periodically), seek out different and opposing perspectives, points of view, new sources and new forms of expression. For example, follow multiple/opposing news sources, politicians and advocacy groups. You can also access sources (e.g., allsides.com) specifically created to provide multiple perspectives. Plugins, such as Escape Your Bubble and Flip Feed, are designed to insert diverging perspectives into your Facebook or Twitter feed.

• Bring attention to under-represented stories and viewpoints. Social media provides a significant opportunity to move outside of traditional news structures. You can leverage the reach of social media to educate others on stories and perspectives that they may not be aware of. If you decide to do this, you must use your critical thinking skills and share stories that help humanise issues. Companies and institutions are involved in making algorithms less likely to amplify one perspective. In the meantime, an awareness of how these algorithms work and exploring ways to break out of your bubble-at least occasionally-can help build a digital world that supports pluralism.

Finally, teachers were encouraged to zone in on their school and identify the multiple ways exclusion can be experienced and reinforced in a school setting, evaluate the challenges of addressing exclusion in their school community and create an action plan to address one example of exclusion in their school community.

Throughout this course, lesson plans were created by the participants, which were shared and commented on by fellow participants and the course coordinators. We also commented on the readings and applied them to our contexts.

I was at the time very involved in facilitating pluralism in my school, as a history teacher in the classroom and as a member of the school's transformation committee. It was beneficial to reflect on our approaches as I did the course.

Some of my key takeaways were:

• Applying a pluralism lens to education points to the importance of looking at what is being taught, how it is being taught, and the extent to which educational institutions model and lay the foundation for pluralistic societies. Both hardware (e.g., legislation, policies, hiring practices, curriculum/textbooks, monitoring mechanisms) and software (e.g., norms, beliefs, attitudes, language, historical narratives) can either facilitate inclusion or exacerbate tensions and deepen social exclusion through simplistic or negative perceptions of and responses to difference.

• The idea of creating a safe space in one's classroom for exploring such issues was important, and, in addition, for many who attended the course, the course became a safe space. Most participants confirmed that this training made them more self-aware. Participants also commented several times through the pilot that the experience provided them with a (brave) space where they could share in a vulnerable way about personal, political and social issues. This, in turn, led to an openness to learn and positively impacted their experience. For example, some people were more comfortable speaking openly about sexuality and gender than others. Such differences can make people try to play it safe and limit conversation or ignore an issue altogether. Establishing ground rules for engagement during this course helped.

Applying a pluralism lens in the classroom

One of the topics I was teaching at the time of the course was Social Darwinism, and I applied some of the tools to see if it helped the quieter pupils voice their thoughts. I used "what perspectives are missing from this discussion"?

It led to previously quiet mixed-race children and children of Indian origin asking lots of questions about the racial hierarchy created by Social Darwinists and trying to work out where they would have been placed and how they are viewed today. Too often, a class's larger or largest group will dominate the discussion. I find the tools developed by the course on pluralism heighten one's consciousness to constantly look for the hidden voices in the class, encouraging all voices to be equally heard and previously silent voices to emerge, thereby decolonising the curriculum.

I was running an elective for Grade-8 learners (13-year-olds) on Voices Across the Ocean, which included looking at Hydro-colonialism. The course inspired me on pluralism to explore slavery not only across the Atlantic Ocean but also the Indian Ocean and the indentured labourers brought to South Africa by the British. I had Joanne Joseph as a guest speaker to talk about her book Children of Sugarcane, a historical novel focussing on the journey and experiences of two Indian women brought to SA. Joanne spoke to the learners and then also talked to parents and the interesting thing was that she seemed to have opened a topic that Indian parents have not been able to address. So many women divulged how they don't talk about this past of their ancestors because it is painful history.

I also invited professor Isobel Hofmeyr to talk about Hydro-colonialism and how many people of colour consider the ocean a spiritual place because of the drowned souls in its depths. This has led artists such as Jason de Caires Taylor, Estabrak El Ansari and Pinar Yoldas to try and depict the people below the ocean.

Others have tried to resist oil companies drilling in the ocean's depths and disturbing these souls. Recently, a service was held in Cape Town to commemorate the 200 slave souls lost at sea when the Portuguese slave ship sank off the coast in 1794. (Smith, 2015)

I also spoke of noise pollution in the ocean and how this affects the life of whales and their breeding habits.3

Finally, I organised an online classroom chat between my students and students from a school in Connecticut to discuss how the different education curricula covered slavery and how this impacted their historical consciousness. Here the students became the voices across the ocean. The elective wrapped up with students writing poems about their view of the ocean after the elective, and it was fascinating to see how many diverse voices emerged.

Reflection from a facilitator:

As reflected by Dr Daniel Otieno Okech:

The evaluations done by the participants revealed that the six modules equipped teachers with competencies related to pluralism, but it also facilitated global connections and built a network of pluralism education champions. Although the course did not explicitly cover decolonisation as a topic, the fact that participants dealt with equality and inclusion made it possible to weave in the discourse about decolonisation. Through these programmes, participants learnt a lot in the areas of intercultural awareness and understanding of global issues such as climate change, pluralism, immigration crisis, racism etc. It provided an opportunity to navigate digital technologies through collaborative tools across different continental regions and time zones. This experience has made me a better educator and a facilitator of global learning.

Possible ways forward:

The GCP evaluates the pilot course and considers whether it should be offered globally or regionally.

It would be important in future courses to look into a language tool to make translation easier for non-native English speakers.

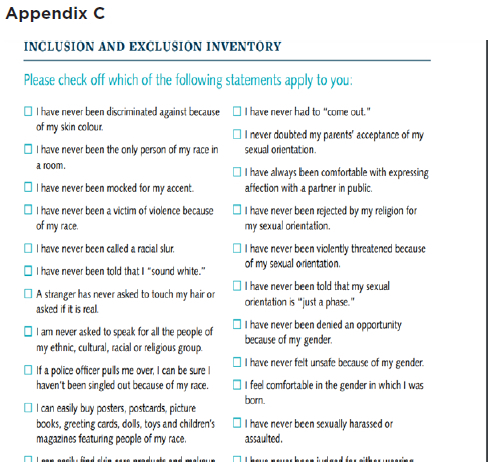

A pluralism inventory was created for use in Canada and the USA that could be changed and adapted to a SA setting but contained questions which can lead to discussion. This is useful for whole school consciousness-raising, about transformation, for teachers and pupils alike, but it may need to be adapted for schools beyond North America and Europe. (See Appendix C)

The inventory is followed by discussion questions:

Were there any questions that made you feel uncomfortable? If yes, why do you think that is?

How does this inventory help us understand the concept of pluralism? Are any questions missing, in your opinion? Are there any questions you would add that would be relevant to your context?

Conclusion

The course on Teaching for Belonging helps heighten one's sensitivity to issues that one may intrinsically know about the importance of addressing diversity in the classroom in a positive way. It aids a teacher's approach and facilitation skills and has practical tools to assist teachers who would otherwise shy away from difficult discussions with learners. It also creates a global network of voices, who could become a network of educators sharing resources and lessons or even just sharing perspectives as guest speakers.

References

Garuba, H 2015. What is in an African curriculum? Mail & Guardian. Available at https://mg.co.za/article/2015-04-17-what-is-an-african-curriculum/ [ Links ]

Joseph, J 2021. Children of sugarcane, Jonathan Ball Publishers. [ Links ]

O'Dowd, R 2018. From telecollaboration to virtual exchange: state-of-the-art and the role of UNICollaboration in moving forward. Journal of Virtual Exchange, Research-publishing. net, 1:1-23. Available at https://doi.org/10.14705/rpnet.2018.jve.1 [ Links ]

Smith, D 2015. South Africa beach service to honour slaves drowned in 1794 shipwreck. The Guardian. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jun/01/cape-town-beach-service-honour-african-slaves-drowned-1794-shipwreck. [ Links ]

1 EuroClio. Available at https://euroclio.eu/

2 Global Center for Pluralism. Available at https://www.pluralism.ca/.

3 Ocean Care, 2022. Available at https://www.oceancare.org/en/south-african-court-bans-offshore-oil-and-gas-exploration-by-shell/.