Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Yesterday and Today

On-line version ISSN 2309-9003

Print version ISSN 2223-0386

Y&T n.28 Vanderbijlpark Dec. 2022

CONFERENCE REPORTS

Conference Report: The 36th South African Society for History Teaching (SASHT) Conference 29-30 September 2022

Venue: Genadendal Museum

Organisers: Francois Cleophas (University of Stellenbosch), Vanessa Mitchell (Robben Island Museum), Judith Balie (Genadendal Museum), and Isabella van der Rheede (University of Stellenbosch))

The 36th South African Society for History Teaching (SASHT) conference welcomed delegates from 29 to 30 September 2022 from across the history education sector to the historic and award-winning Genadendal Museum. The conference's focus was to respond to a changing 21st century, which is experiencing environmental threats, pandemics, and increasing wars. Hence the conference theme of History Teaching in and Beyond the Formal Curriculum is underpinned by the following sub-themes.

• history teaching in the formal school curriculum, history teaching in the informal school curriculum, unofficial history teaching

• history teaching for a decolonising school curriculum, history teaching in private and state museums, history teaching pedagogies in the disciplines, e.g., environmental studies, fine and performing arts, heritage, medicine, sport studies, war, religion, nutrition, etc.

• open papers on history education themes not covered by the above

The conference was attended by 80 attendees from schools, museums and universities across South Africa and 32 papers were delivered. See the image below.

During the parallel sessions across the two days, papers were delivered focusing on private and state museums and the informal school curriculum, the environment and e-learning, decolonising school curriculum, the formal school curriculum and history education and teaching pedagogies and history education. The papers and presenters from various disciplines made for fascinating discussions and debates. Debates took place about what a decolonised history curriculum in schools should be, including military history in higher education, building relationships between schools (history teachers), museums, and universities and using e-learning pedagogies.

'Conference attendees of the 36th SASHT Conference in front of the Genadendal Church.'

Two powerful keynote addresses were also delivered during the conference. In the first, Professor Howard Phillips of the University of Cape Town spoke about Black October: the Spanish Flu Pandemic of 1918 in South Africa-the intersection of global, national and local history. In the second, the activist and scholar Gertrude Fester engaged with Toa Tama !Khams Ge-the struggle continues.

The conference went well, given the limited resources available to history education and history educationists and the issues surrounding load shedding. The success of this conference was due to the synergy between the organising partners (Robben Island Museum, Stellenbosch University, and Genadendal Museum). The importance of student assistants who are keen and willing to undertake tasks cannot be emphasised enough. The social gatherings were also successful since networks were established and re-established, and informative institutional experiences were exchanged.

Report: Black Archive1 Symposium 4-5 August 2022

Venue: Crawford's Beach Lodge, Chintsa-East London, South Africa

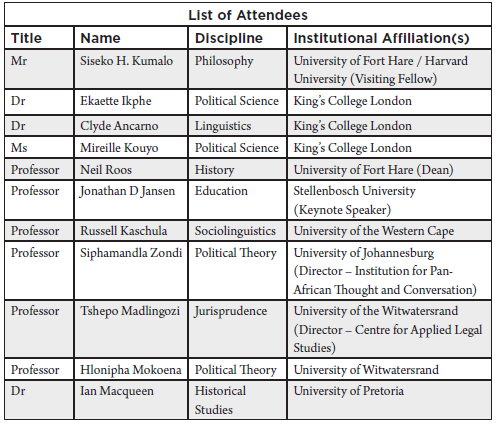

Convenor: Siseko H Kumalo (University of Fort Hare, Philosophy Department | Harvard University, Centre for African Studies); ISBN: 987-0-9947240-8-3

Overview

The Black Archive symposium was conceptualised to draw different disciplinary expertise into thinking about the next move in decoloniality insofar as decoloniality is articulated in South Africa. This conversation sought to challenge claims made in the South African academy as a way of mystifying and obfuscating the voice of Black/Indigenous intellectuals, an obfuscating move that is found in the claim that the meaning of decolonisation is not clear. As such, the symposium was organised to bring to light the reality that the historical articulations of decoloniality in the country are deeply embedded in the hopes and ambitions of Black/Indigenous intellectuals-who continued to write about the fact of Blackness even as they were excluded from formal sites of knowledge production, i.e. the South African University. In framing the meaning of decolonial demands in this way, the conceptual articulations found in the scholarship of both the work of Phiri (2020) and Etieyibo (2018) are not only challenged but also subjected to scrutiny. In a review essay on African Philosophical and Literary Possibilities (Kumalo 2020a, 164), I suggest that "a superficial, yet positive takeaway from [the way in which the category of decolonisation is treated in the book], is the popularisation of decolonisation as a thematic area of engagement". Put in another way, "[t]he shortcomings with this approach, however, are a rendering of the movement-both in its theoretical and praxis-based analyses-as a vapid and empty signifier that continues the project of colonial violence, which was predicated on the erasure of native (Black/Indigenous) subjectivity" (Kumalo 2020a, 164). To be sure, Blackness/Indigeneity has articulated what is intended by the concept of decolonisation, an articulation that has been seen time and again in the writings of scholars like Tiyo Soga, JT Jabavu, Magema Fuze, William Wellington Gqoba, Samuel, EK Mqhayi and Herbert Dhlomo as but a few examples.

To claim that the meaning of decolonisation is not clear (which is what the reader will find in the texts of both Phiri (2020) and Etieyibo (2018), as cited above) is not only an insult but further exacerbates the erasure of Black/Indigenous ontology in the academy. Subsequently, the objective of undertaking such a historical analysis is to showcase how South African Black/Indigenous intellectuals can contribute to the global aims and objectives of a decolonial, global higher education system. The global higher education system needs alternative perspectives, first articulated by Bill Readings' (1996) timeless analysis in The University in Ruins. Without going into the finer details of the neo-liberal, corporatised higher education system, what is apparent is the need for a global humanities that attends to the human condition if we are to borrow from Hannah Arendt's framing. The critique here is that the humanities fail to respond to the realities of the human condition, owing to how we have monetised knowledge development. The Black Archive looks back into this history, but from a vantage point that corresponds to the needs of historical justice, offering us global futures that are interested in a sustainable developmental trajectory that does not suffer from the marauding ideologies of colonising logics.

This project is global in its orientations, witnessed in how this symposium was held in partnership with the African Leadership Centre at King's College. We identified the challenges that the global academy comes up against when treating the subject of decolonisation. In convening this symposium, we recognised that contexts like the United Kingdom could legitimately claim that decolonisation-in the context of the scientific systems of Europe-needed definitional clarity, which could come from an articulation of decolonisation in the global South (South Africa). More importantly, such an articulation transcends the critique that has been witnessed in decolonial circles the world over. Such a framework is rooted in the understanding that colonisation, as a historical fact, took place and that its existence has been traced in the scholarship of countless post-colonial and decolonial theoreticians. In recognising this gap, the Black Archive seeks to fill it by initiating a global conversation that attends to the needs of the global humanities. Recognising this gap and having initiated the initial global partnerships accord, insofar as this project is concerned, the co-lead of the Faculty of Social Science and Public Policy Decolonisation Workstream, Ekaette Ikpe (Director of the Africa Leadership Centre at King's College), framed the aims of the Workstream-in her opening and welcome remarks-thusly:

Developing diverse curricular, pedagogical approaches and [being inclusive of] diverse student experiences [is the intention of the Work-stream]. This includes actionable work/initiatives toward the decolonisation of curriculum as well as consensus at what is intended by the concept of decolonisation. This is undertaken through an ongoing engagement with staff and students, in debates and critical discussions on decolonisation, which includes reflections on the make-up of disciplines in the faculty.

There are two things to be said about these remarks. First, in the context of the United Kingdom, the concept of gaining clarity on what is intended by decolonisation is clear in relation to the fact that historical reality necessitates intercultural exchange. Simply put, this partnership allows for an inter-epistemic dialogue wherein those at the centre create platforms that exude epistemic humility insofar as this humility means the capacity to learn from those who've always been situated at the margins of knowledge development. For these reasons, King's College-through the Faculty of Social Sciences and Public Policy-would want to invite diverse student experiences to move beyond the hegemonic ontological and cultural experiences that might have dominated the institution since its founding. Herein lies the first point of observation concerning what the debates of decoloniality-as emanating from the South African context-can bring to our global partners; an ability to articulate a meaning of decolonisation informed by the experiences of those who are located at the margins. This is also true concerning the aims and objectives of the research agendas of our partners in the global South and north. Concerning interrogating disciplinary knowledge and methodological foundations in our disciplines, this was an explicit objective of the symposium, as it was conceptualised from a body of scholarship concerned with the meaning of disciplinary knowledge, how it is organised and to what end it is organised. This interrogation of knowledge gives us the second observation concerning Ikpe's opening remarks.

A point of convergence came again in Ikpe's remarks concerning the requirement of King's College London to be responsive to the global trajectories of disciplines while also being responsive to the local conditions of the United Kingdom. This is articulated as follows by Kumalo (2021a: 4) "Research and development, specifically within the humanities and social sciences, has neglected to be responsive to the local challenges of our society". Moreover (Kumalo 2021a: 7)

This [balancing act, which denotes an awareness of global trajectories while being responsive to local concerns] approach does not entail dismissing and neglecting western epistemic paradigms but suggests [a dialogical exchange] with local epistemic positions as opposed to [the north] continuously dictating the terms of engagement.

This mutuality is witnessed in our collaborative efforts, as the University of Fort Hare's Philosophy Department (jointly hosting the project with the University ofJohannesburg's Institute for Pan-African Thought & Conversation) is working with the African Leadership Centre at King's College London. The African Leadership Centre has been dedicated to developing peacebuilding and state-building mechanisms for over a decade. In thinking about the questions of ''what is the role of the state in [working toward] stable peace?'' and ''how is society impacted by the state [...]", understanding the ontological and epistemic positions of those who experience the African state is imperative. In responding to these questions, we hope to revitalise and reconceptualise the function of the humanities in the modern world.

This returns us to the dismissal and erasure of Black/Indigenous ontology-be it because of answering the questions above or in the process of knowledge-making in South Africa, the intention of drawing in different disciplinary perspectives was underpinned by two principles. First is the desire to go beyond the critique (cf. Kumalo 2020b). Here, the reader finds, in the scholarship of those who contributed and continue to contribute to the Black Archive, articulations that go beyond the critique and begin to frame what a decolonial world might look like. In imagining this new world, it is important to note that said articulation could enrich the way the world understands and contributes to global problem-solving. We are informed by Mignolo's thinking around world-making, which is associated with decoloniality as praxis. The imperative, therefore, is on us as decolonial scholars-those of us who are seriously engaged in this area of work-to deferentially work with the contributions of Black/Indigenous South Africans (and peoples of the margins), surface their contribution while demonstrating both its usefulness and drawbacks. This would be done to realise the objective of historical justice insofar as such a demand would actualise the hopes of decolonisation. The second move was to ensure that while the South African decolonial agenda draws from the scholarship and thinking further afield, it also privileges the voices of our context. It is here that Hlonipha Mokoena's work on Magema Fuze becomes a central tenet that contributed to the conceptual articulation of decoloniality as it is found in the Black Archive, vis-à-vis the Black Archive symposium.

Defining the Black Archive

As highlighted by our keynote speaker (Jonathan Jansen), my scholarship's definition is similar to the one we find in the Black Archives Project, developed in the Netherlands. I suggest that "the Black Archive facilitated the act of thinking through and theorising the Fact ofBlackness, even as Blackness/Indigeneity has existed and continues to exist at the margins of knowledge production" (Kumalo, 2020c: 2). Furthermore, my definition outlines that "Blackness/Indigeneity, through poetry, literature, music and art continued to think about conditions of oppression and injustice, while aiming at curating a world that would signify the 'ontological recognition' (Kumalo, 2018) of Blackness/Indigeneity" (Kumalo, 2020c: 5). Since I have demonstrated these points in the case of Defining an African Vocabulary; Curriculatingfrom the Black Archive; Resurrecting the Black Archive through the Decolonisation of Philosophy in South Africa, and most importantly, Khawuleza-An Instantiation of the Black Archive, I will not recite the definitional position in this report. Save to say that this area of scholarship is growing, demonstrated by the number of participants who contributed to the symposium. While we must acknowledge the differences in terminology, with respect to how these facets of the Black Archive have been treated by scholars in a series of disciplinary constitutions-i.e., African languages and sociolinguistics, art history, historical studies and historiography, jurisprudence, philosophy, political theory, and educational theory, we have all applied ourselves to similar permutations. We are all interested in spotlighting the contribution of Black/Indigenous intellectuals to the extent that they thought about the fact of Blackness and how that thinking might inspire contemporary responses to sociopolitical challenges. More importantly, the nature of the South African colonial experience helps inform the development of the disciplines in the arts, humanities and social sciences. The arts, humanities and social sciences in South Africa shaped and created a deeply divided society. The suggestion, therefore, is that we can use these tools to re-imagine new possibilities. Such a project of imagining will require our moving beyond the restrictions of disciplinary divides and towards collaborative efforts that harness the methodological tools of each of the contributing disciplinary sets that constitute this project.

Aims and Objectives

As already outlined above, the aims and objectives of this symposium lay in challenging and dislodging claims that would have us believe that the meaning of decolonisation is indecipherable in our context. I would suggest that this claim is a thinly veiled attempt at re-colonising the intellectual landscape with respect to the academy's failure to recognise what I have termed the 'ontological legitimacy' (Kumalo, 2021b) of Blackness/Indigeneity. This concept denotes the capacity for Black/Indigenous South Africans to speak for themselves regarding their life expectations, experiences, and realities.

To frame the intellectual project of Blackness/Indigeneity thinking about itself as nationalistic/parochial stems from the reality that South African intellectual circles have constantly been concerned with replacing the legitimate voice of Blackness/Indigeneity with the voices of others. Blackness/Indigeneity, it would seem, has often been viewed as credible only to the extent that it is a native informant-that is, there are processes of de-legitimation in the country's knowledge economy. This process takes place through the definition of knowledge as knowledge only insofar as it is developed by white scholars, as outlined in Curriculatingfrom the Black Archive (Kumalo, 2020d). Of course, the challenge with this frame of reference is its continuation of the colonial tropes inaugurated at the dawn of colonial incursion. The resistance strategies to this reality are found in the writing of Black/Indigenous intellectuals who were writing against the oppressive regimes of colonial masters and cultural imperialism that sought to exterminate the cultural existence of Blackness/Indigeneity.

Resultantly, the symposium was organised with the intention (aim) of dispelling this myth that knowledge is knowledge only insofar as it is developed by white scholars while also organising around two main objectives. First, an understanding of the critical voices contributing to the corpus of knowledge explicitly profiling the historical accounts of Blackness/Indigeneity. This is in relation to the thinking and scholarship of those who were engaged in the process of documenting the process of cultural colonisation and developing work that acted as resistance tools-tools that are used now as Inqolobane Yolwazi (Black Archive)-even as they were excluded from formal sites of knowledge.2 This objective is in line with Wicomb's suggestion (2018/[1993]: 65) that we need "a radical pedagogy, a level of literacy that will allow our children to read works of literature that will politicise them into an awareness not only of power, but also of the equivocal, the ambiguous, and the ironic that is always embedded in power". Framing the first objective in this way expresses the requirement to bring together a set of disciplinary expertise in thinking with/about historical moments that culminate in contemporary decolonial struggles. Still, it is important to note that those working in these disciplinary areas might not explicitly conceptualise their contribution to decolonisation as decolonial scholarship. The work done by these colleagues is, however, decolonial to the extent that it expressly speaks back to the second objective of the symposium, which was to work beyond the disciplinary frameworks instituted by/in the contemporary university. For these reasons, a series of scholarly disciplines in the Arts and Humanities were brought together to think through the contribution that can come from thinking about the scholarship of historical Black/ Indigenous intellectuals.

The second objective was to bring together people working in this line of thinking, even as we might each refer to it differently. What informed this decision was the importance of reading beyond and outside the disciplinary ambits that structure modern knowledge development institutions. Put simply, as we have all theorised that contemporary decolonial scholarship seeks to "re-member" (cf. Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2015 & Kumalo, 2020b) insofar as said knowledge is dedicated to the reconceptualisation of the meaning of Blackness/ Indigeneity, its ontological legitimacy, and the constitutive aspects that would speak to the development of knowledge that is responsive to the local needs of our people. Such an orientation, as was already outlined above, does not take away from the necessity to focus on the global disciplinary trajectories that inform the disciplines in which we are situated.

A Methodological Discussion of Conceptual Clarification(s)

Coalescing philosophy, jurisprudence, educational theory, political studies and theory, history and historiography, linguistics and sociolinguistics, this symposium was organised to go beyond these disciplines. The intellectuals who contributed to this emergent area of scholarship have each contributed substantially to the development of knowledge that concerns the lives of Black/Indigenous South Africans to the extent that their research objectives and agenda are responsive to the realities of our context.

Thinking with the local conditions, my work has centred on the requirement to respond to these while actively pursuing the capacity to influence global disciplinary trajectories in philosophy. The pursuit of this objective was inspired by the reality that the global academy can gain substantial insights when thinking alongside the perspectives that inform our local context. For this reason, the symposium drew from the scholarly concerns and thinking of Tshepo Madlingozi; a scholar who has been informed by the objectives ofreconceptualising the legal frameworks that underpin the transformation (or lack thereof) of our society (cf. Madlingozi, 2017; 2018). In thinking about our societal challenges, Madlingozi inquires (2017: 123), "What time is it? The thesis defended in this article is that apprehended from the lived experiences of South Africa's socially excluded and racially discriminated: this is the time of neo-apartheid constitutionalism". In the footnote that accompanies this introductory line, Madlingozi is careful and systematic in explaining that:

In section one of this article, I explain what I mean by neo-apartheid constitutionalism, and in part three I show how social justice, transformative constitutionalism's master frame for social emancipation, is complicit in the perpetuation of an anti-black bifurcated society. In response to an anonymous reviewer's suggestion that I should immediately make it clear whether I think that systemic racism continues today, I wish to state the following: the epigraphs to this article, my reference to the time of neo-apartheid and the rest of this introductory section make it clear that indeed I do believe that this is the case. For recent empirical evidence see chapter 3, "Black pain and the outrage of racism" in Swartz Another country 45-68. In this article, I invoke the lived experiences of members of Abahlali baseMjondolo - the twelve-year-old, approximately 10 000-strong social movement of shack dwellers - to demonstrate firstly, that impoverished black people still suffer racialised dehumanisation and social invisibility, and secondly, that the ruling elites are responsible for maintaining this world of apartness.

In framing his discussion through an explicit acknowledgement of the persistent continuance of systematic racism in the country, Madlingozi is instructive in allowing us to see what is meant by the concept of the denial of ontological legitimacy, as it is denied the majority. His analysis and frame of reference-which demonstrate the point of a denial of the ontological legitimacy of Blackness-are the reality that (Madlingozi, 2017: 124) "those confined to the 'other side of the line (the 'zone of non-beings) suffer unremitting dehumanisation and social invisibility". Moreover, and in stressing the point "[a]ccording to Abahlali baseMjondolo (Abahlali') [...] - an other-side-being is a being who continues to be pushed below the line of the human, a humanoid whose 'life and voice do not count'". What is surfaced by Madlingozi's scholarship is the reality that the basic services and needs of those on the 'other side' are not only neglected-they do not even feature in the purview of those who inherited an apartheid state. Concerning ourselves with the realities of South Africans becomes a primary focus of the work undertaken by the Black Archive insofar as this work aims to develop scholarship that is responsive to the conditions of the majority.

The dismissal of the ontological legitimacy of Blackness/Indigeneity is intimately interwoven with the worldview that structures the world. Such a worldview, in our context, is premised on the colonial settler's identity, language and systems of thought and writing. This is to say that the component of language, as a communicative device, but also as a cultural encoding system-a system of encoding insofar as such a system determines the scientific systems of possibility that exist-serves as a powerful tool. In developing historical accounts and having those accounts inform the national ethos of belonging and identity, it is imperative to inquire into the historical accounts that exist in re-imagining our worlds. From a historiographical perspective, Ian Macqueen (2019) is instructive in his scholarship when he argues that our teaching of history and historical writing should be drawing from sources that were previously excluded from knowledge production. Drawing from the work of Bradford and Qotole (2008), he makes a case for the use of texts written in African languages, citing that "such African-language accounts illuminate much, formidable linguistic barriers to their full appreciation nonetheless exist". More importantly and instructively, he argues that "[t]he linguistic barriers of translation are a matter of priority of course; consider the commitment of scholars of other regions of the world to the study of orthographies of their old languages. Thus, the excuse of impracticality or difficulty cannot be sustained"

In making this case, Macqueen is instructive in demonstrating the usefulness of language as a tool allowing us access to alternative forms ofhistoriography. Such alternatives could allow us to imagine new possibilities as we are interested in crafting global humanity that attends to the human condition. Alternative sources for historiography and historical writing are not without their challenges. As the reader will recall from footnote 1 of this report, Apter's (2013) concept of untranslatables becomes a point of interest concerning some of the barriers Macqueen discusses in his work. More importantly, however, Macqueen's work also demonstrates a useful point concerning the role of teaching as a source of innovative research methods. In using the space of teaching and learning, as one that is generative of ideas that are responsive to the local context, the reader begins to understand the importance of not only the inclusion of Macqueen's work in this project but as a stand-alone testament to what intellectuals can do with the teaching and learning space.

The inclusion of materials from history and historiography, jurisprudence and philosophy demonstrate the contested nature of knowledge-making in the academy. If we are to craft new possibilities, our systems of thought need to draw from each of these disciplinary positions to position the task of world-making as best as we can. This point is best detailed by Zondi's thinking-in his recent bookAfrican Voices: In Search of a Decolonial Turn. He sums up the point of what we have been trying to demonstrate here well when he writes (Zondi, 2021: 3), "[n]otions of power, being and knowledge within coloniality/ modernity are built on violence -in the form of both genocide and epistemicide". In combating how we have come to understand the structures that inform and influence knowledge development, insofar as knowledge development is intended to be in service of the needs of society, Zondi (2021: 5) follows Zaleza in arguing for the process of "stripping this tradition [i.e., western universalisms] ofits universalistic pretensions and universalising propensities". Furthermore, he suggests that such a process "must also entail a combative insistence on speaking from the position of Africanicity, which is both an ontological and an epistemological strategy.". The strategy that we find in Zondi's work is aligned with the aims and objectives of the Black Archive insofar as our work is aligned with the objectives of centring and spotlighting the voices of Blackness/Indigeneity in the South African context.

African voices have, for the longest while, been silenced by fears of essentialist thought insofar as African conceptual and intellectual interests become essentialist when the process of thinking about our conditions and our histories is undertaken by Black/ Indigenous intellectuals. Zondi's scholarship demonstrates that such erasure systems are not novel and new. The point being demonstrated here is that a systematic application to the writing of Black intellectuals will demonstrate that the voices of Blackness/Indigeneity have been silenced, erased, and removed from scientific contribution for fear that Black/ Indigenous scholars will displace those who actively work to undermine the ontological legitimacy of Blackness. As part of this erasure, in the process of thinking with the Black condition, African intellectuals have often been accused of doing ethno-philosophy, deploying ethnocentric gazes in the disciplines of anthropology and sociology. In contrast, other disciplines have accused such systems of thinking as being guilty of naval gazing projects that are non-scientific. As Ndlovu-Gatsheni (2018) demonstrates, however, in his Epistemic Decolonisation, the most ethnocentric of scientists is the European colonial intellectual, who-in contravention of Bertrand Russell's suggestion (1912), as we find it in the timeless essay The Value of Philosophy-are unable to fulfil the project of expanding oneself and fulfilling the desire of philosophic contemplation by way of reaching beyond the familiar and the known.

In simple terms, the political, related to knowledge development, serves the function of gatekeeping while arguably styling the epistemic positions of those who enjoy more influence and power in the academy as something natural. In simple terms, politics underpins the processes by which we come to include and exclude specific knowledge systems. More importantly, it surfaces the critical question that concerns the delegitimating claims of those who style the work undertaken by and within the Black Archive as symptomatic of processes of nationalism or some parochial project of little intellectual import. In responding to such forms of styling, work was undertaken to respond and engage with the intellectual corpus of Black/Indigenous intellectuals in our country. The question must be asked concerning power. Who benefits from having academe believe that such work-when undertaken by Black intellectuals-is parochial, essentialist or nationalist in its orientations? Who derives further legitimation when we cannot effectively engage with the historical vision that some of our intellectuals had articulated for the future of a democratic South Africa? Who continues to be on the receiving end of oppressive state organisation systems when we neglect to take the concerns of our local communities seriously insofar as we style the intellectual enterprise as knowledge for knowledge's sake?

In response to these questions, the Black Archive's methodological approach brought together leading intellectuals in the fields of philosophy, jurisprudence, educational theory, political theory, linguistics and history and historiography (as a study method). Where such work has been articulated in the past, it has been found in the thinking, writing and literary achievements of some of the country's leading Black/Indigenous literati. For these reasons, some of the work that comes out of the project borrows heavily from literature, literary theory, and critique. The reasoning is that in these areas of consideration, the reader finds a meaningful way of reading and understanding the South African condition without being confined to the disciplinary divides that constitute knowledge as it is developed in the western academy. In simple terms, such a coalescence of disciplinary voices, with each contributing a crucial part of the puzzle, allows for the reconceptualisation of the knowledge project itself, as it is undertaken on the southernmost tip of the African continent. Simply, ours lies in developing knowledge that is responsive to the conditions of our people, an idea that speaks back to how knowledge was not only understood but also used by our forefathers. Such a conception of knowledge is derived from Mazisi Kunene (1996: 16) when he reminds us in his briefbut erudite piece on Some Aspects of South African Literature that "[w]ritten literature by Africans in the earlier period when literacy was low, had a surprisingly great significance and relevance". Here Kunene was pre-empting the timeless and useful observation found in Hlonipha Mokoena's work (2009) when she wrote of An Assembly of Readers: Magema Fuze and his Ilanga lase Natal Readers. This observation is made because ofthe later proposition that we find in Kunene's (1996: 16) analysis when he writes, "[o]n the contrary, to Africans, written literature violated one of the most important literary tenets by privatising literature". This is because of the reality that within the Zulu literary genre, one can pick from an array of five styles as they are treated by Kunene (1979: 316) himself: i.e., indaba (a popularised story), inganekwane (a tale) insumansumane (a fantastical story or tale), inkondlo (poetry/a poem) or umlando, (which is a stylised historical narrative). Simply then, the methodology deployed in this research project seeks to attend to the requirement that knowledge speaks back to the context in which it is developed. Because of this, we are not blind to the reality that said knowledge needs to keep in mind the disciplinary trajectories in which we work. Considering this balancing act, we hope this research project will lead the way in conceptualising how knowledge disciplines can collaborate to solve some of the wicked problems that afflict our contemporary societies.

The Black Archive is conceptualised as a thematic area of study that will respond to the realities of the South African contemporary state while also giving the global academy insightful knowledge that responds to the demands that our knowledge systems be decolonised. This project inspires new questions, one of which is considered (elsewhere) as ''the Decolonial Problem". This is to say that the decolonial problem is interested in investigating how the knowledge we are uncovering from the continent, the Latin American worlds, the East and Arabia-how this knowledge is being used in the academy. In simple terms, is this knowledge being used in service of western philosophical problems and questions, or is it attending to the needs of the epistemic grids that give rise to this knowledge in the first instance? What is of crucial importance is an understanding of how we deal with the response that we get from the previously posed question. If said knowledge is in service of the western enlightenment and intellectual project, which is underpinned by systems of thought that gave us the violence of colonialism, extractivist thinking, and hyper-individualised societies that are dysfunctional owing to the reality that the human- as species, is a highly sociable creature-how then are we to treat a response that says our knowledges are in service of the western scientific structures of thought?

Conclusion

The Black Archive symposium, an event convened at Crawford's Beach Lodge in Chinsta, Eastern Cape (South Africa), sought to grapple with the questions that arose from the preceding discussion. In bringing together, colleagues who are each thinking about the implications of knowledge production, and systems of thinking that are aimed at responding to the realities of the people, the world over, the hope was that we could spotlight and learn from the intellectual corpus of Black/Indigenous South Africans, most of whom were writing in their native languages. Our collective access to this knowledge has meant that we are privileged enough to not only still be able to read and engage with this knowledge but that we can disseminate it in ways that allow us to attend to the principal conception of knowledge, as it was held and developed on the continent. That is to say, through the knowledge produced from this project, which is still in its infancy stages, we can respond to the requirements of aiding the global academy in achieving the goal of decolonisation.

References

Apter, E S 2013. Against world literature: on the politics of untranslatability, London and New York: Verso Books. [ Links ]

Etiyeibo, E 2018. Decolonisation, Africanisation and the philosophy curriculum. London and New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Kumalo, S H 2021a. Developing epistemic impartiality to deliver on justice in higher education South Africa. Education, Citizenship and Social Justice. Available at https://doi.org/10.1177/17461979211048665. [ Links ]

Kumalo, S H 2021b. Contestations of visibility-a critique of democratic violence. South African Journal of Higher Education 31(1):143-160. [ Links ]

Kumalo, S H 2020a. Distinguishing between ontology and 'decolonisation as praxis'. Tydskriff vir Letterkunde 58(1):162-168. [ Links ]

Kumalo, S H 2020b. Decolonisation as democratisation: global insights into the South African experience, Cape Town: HSRC Press. [ Links ]

Kumalo, S H 2020c. Khawuleza-an instantiation of the Black archive. Imbizo: International Journal of African Literary and Comparative Studies 11(2):1-21. [ Links ]

Kumalo, S H 2020d. Curriculating from the Black archive-marginality as novelty. Critical Studies in Teaching and Learning 8(1):111-132. [ Links ]

Kunene, M 1996. Some aspects of South African literature. World Literature Today 70(1): 13-16. [ Links ]

Kunene, M 1979. Review: content and context of Zulu folk narratives by Brian M Du Toit. Research in African Literature 10(2):314-320. [ Links ]

MacIntyre, A 1988. Whose Justice? Which Rationality?, Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. [ Links ]

Macqueen, I M 2019. Testing transformation and decolonisation: experiences of curriculum revision in a history honours module. Yesterday & Today 22:1-18. [ Links ]

Madlingozi, T 2017. Social justice in a time of neo-apartheid constitutionalism: critiquing the anti-Black economy of recognition, incorporation and distribution. Stellenbosch Law Review 28(1):123-147. [ Links ]

Madlingozi, T 2018. Mayibuye iAfrica?: disjunctive inclusions and Black strivings for constitution and belonging in South Africa. (Doctoral dissertation, Birkbeck, University of London). [ Links ]

Mokoena, H 2019. An assembly of readers: Magema Fuze and his Ilanga lase Natal readers. Journal of Southern African Studies 35(3):595-607. [ Links ]

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, SJ 2018. Epistemic freedom in Africa: deprovincialisation and decolonisation. London and New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S J 2015. Decoloniality as the future ofAfrica. History Compass 13(10): 485-496. [ Links ]

Phiri, A (ed.) 2020. African philosophical and literary possibilities: re-reading the canon. Rowman Littlefield. [ Links ]

Russell, B 1912. The problems of philosophy. London: Williams and Norgate. [ Links ]

Wicomb, Z [1993]/2018. Culture beyond colour? A South African dilemma. In A Van der Vlies (ed.). Race, nation translation: South African essays, 1990-2013. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. pp. 58-65. [ Links ]

Zondi, S d.) 2021. African voices: in search of a decolonial Turn. Cape Town: HSRC Press. [ Links ]

1 Following the thinking ofAlasdair Maclntyre's (1988) 'Tradition and Translation' in Whose Justice? Which Rationality?, it is the object of the concept of an 'archive' to relate the meaning of what is intended by 'Inqolobane! The conceptual understanding is that the materials we engage, as we work with and through the Black Archive, are materials that were stored away, as one would store away and preserve grains in Inqolobane. In this respect we are after commensurability insofar as an African tradition can converse with a western one-with a translatable equivalent being the concept of an Archive in the western tradition. This is not to dismiss Apter's (2013) cautionary remarks about the untranslatability of certain concepts, an argument whose validity is demonstrable in the inadequacies of translating the concept of Inqolobane as an 'Archive'. Inqolobane, is itself-not without contestation-if the reader takes seriously the challenges that were inaugurated by a curated concept of Blackness/Indigeneity that arises because of the apartheid state directing what aspects of Blackness/Indigeneity are permissible and worthy of inclusion into the school curriculum. Such a framing is not to dismiss the work of Sibusiso Nyembezi, who penning Inqolobane Yesizwe, working with Mandla Nxumalo, could be understood as privileging certain conceptions of Zulu identity that would later be institutionalised through systems of standardisation in the school curriculum. This brief discussion on language, translation and the problematic of concepts- even as we find them in L1-is to simply demonstrate the context under which we work, in research on the Black Archive. In simple terms, it is useful to acknowledge and declare that as this concept is relatively new (with respect to its uses in the academy, and as a designator of materials that are both creative and historical in kind), the concept is not without contestation and debate. In acknowledging this reality, we also wish to welcome said debate and contestation on the premise that it will highlight the work of the scholars that we seek to showcase by working in this area.

2 Such a process of the exclusion of Blackness/Indigeneity from academic knowledge started in 1870, when James Stewart took over the principalship of Lovedale-from William Govan. His decision to put Black/Indigenous students on a more "practicaT/vocational training stream was to be the precursor to the Bantu Education Act (1953) and the Extension of University Education Act (1959). One cannot understand the South African condition, of excluding the majority, without first understanding this historical fact, as was premised on Stewart's decision at Lovedale.