Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Yesterday and Today

On-line version ISSN 2309-9003

Print version ISSN 2223-0386

Y&T n.28 Vanderbijlpark Dec. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2223-0386/2022/n28a3

Teaching history in primary schools in Mauritius: Reflections on history teachers' pedagogical practices

Seema Goburdhun

Mauritius Institute of Education, Port Louis, Mauritius. Orcid: 000-0003-4574-3513; s.goburdhun@mie.ac.mu

ABSTRACT

Although post-independent Mauritius has witnessed the evolution of the history curriculum, the discipline has still not been accorded the status as in some countries in Europe and Africa. The evolution also marks change and continuity in the content of the history curriculum and how the teaching is transacted in classrooms. This paper informs on the current state of teaching history in primary schools in Mauritius. An interpretivist qualitative methodological approach was adopted to understand the pedagogical choices made by teachers in the implementation of the history curriculum in primary classrooms. Data was generated through classroom observations and interviews with 15 primary school history teachers. Findings reveal the need to draw on a range of knowledge to engage learners successfully in history classes. This range of knowledge they need to draw is extensive and complex. The study shows that teachers' knowledge base is crucial for effective history teaching in classrooms.

Keywords: History Curriculum; Change and Continuity; History teaching; Knowledge base; Pedagogical Practices; Strategies

Introduction

Mauritius, a small island in the southwest Indian Ocean, discovered in the fifteenth century by the Portuguese, underwent successive colonisation by the Dutch, the French, and the British at different periods in time. In 1968, the island obtained its independence from the British and then ensued changes in the different sectors: political, social, and economic. The field of education also did not remain untouched. Mauritianisation of the curriculum and, more specifically, the history curriculum became the priority. Now, at a period in time when the country has celebrated over fifty years of its independence, it becomes imperative to introspect on the evolution of its educational policies, curriculum, and the practice that occurs in the teaching space.

This paper reports on the current state of the history curriculum and, more specifically, on teaching history in primary schools in Mauritius. It attempts to understand teachers' pedagogical choices in the history curriculum's implementation. In doing so, I first outline the purpose of history in the curriculum and examine its evolution in the Mauritian schooling system. Secondly, I discuss the practice that eventually occurs in the classroom.

Literature Review

History is a way of constructing knowledge. It is a vibrant discipline and field of enquiry with ''notions of evidence, a range of interpretive tools and conceptual understandings and ideas about the validity and truth of the claims that we can make about the past'' (Jorn, 2005: 3). Knowledge of history and understanding of the way that historical knowledge emerges matter a great deal for any young person learning what it means to be human and for any society that wants to try and understand itself. MacMillan (2009) and Stearns (1998) argue that the rationale for the inclusion of history in the school curriculum has been based predominantly on the premise that the transmission of a positive story about the national past will inculcate in young people a sense of belonging and a reassuring and positive sense ofidentity. Berg (2019), on the other hand, underscores the various attributes and factors that make history a worthy subject and foregrounds the importance of history in promoting citizenship. Haydn (2012); Bentley (2007); Stearns (1998); Fumat (1997); Stricker (1992); McCully (1978) concur with the view that the study of history helps to develop an understanding students of societal events, movements, and developments that have shaped humanity from the earliest times. On another note, Leinhardt (2001) posits that history allows people to ask and answer today's questions by engaging with the past and imagining and speculating on possible futures. Studying further connects students with the wider world as they develop their identities and sense of place. They engage with history at personal, local, and international levels. The importance of learning history also lies in equipping students with knowledge and skills that are valuable and useful throughout life. These include research techniques, the skills needed to process and synthesise varied and complex materials, the skills needed to give clear and effective oral and written presentations, and the ability to articulate ideas clearly to others. An awareness of history inspires students to become questioning and empathetic individuals. It thus follows from the above discussion that teaching history should enable students to think critically, ask perceptive questions and develop their perspectives and judgment. However, history occupies an ambiguous place in the Mauritian school curriculum. On the one hand, almost all governments expect schools to ensure that students gain an understanding of the past. On the other hand, inadequate time and space are provided for realising the aims and objectives stipulated in the history curriculum.

History in Mauritian School Curriculum

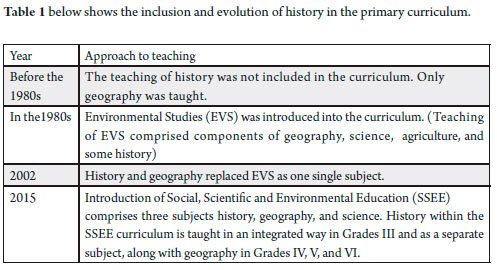

Although post-independent Mauritius has witnessed an evolution in the history curriculum both at the primary and secondary level, it never enjoyed the privilege of being a core subject on its own in the curriculum, as is noted in some African countries, for example, Tanzania (Namamba & Rao, 2017). At the primary level, for a long-time, history along with geography formed part of the Environmental Studies (EVS) programme and was taught using an integrated approach. It was only in 2002 that the two subjects - history and geography- were separated from the EVS curriculum to provide an opportunity to understand better specific concepts englobed in these subjects.

The recent curriculum reform, Nine Years Continuous Basic Education (NYBCE, 2016), continued the trend of the integrative model. As such, history is incorporated in Social Scientific, Environmental Educational programme, which has geography and science as other components at the primary level. At the secondary level, it is included as a component of Social and Modern Studies. The new curriculum (NYBCE, 2016) proposes teaching history in an integrated way in Grade III. For upper primary classes, Grades IV, V, and VI, history and geography are taught as separate components in the textbook with the appellation History and Geography. (National Curriculum Framework, 2015).

The Social, Scientific and Environmental Education (SSEE) curriculum enables learners to acquire knowledge and develop inquiry skills, conceptual understanding, requisite attitudes, and values for a critical understanding of the three dimensions of the environment: natural, cultural, and social. History, Geography, Science, and Environmental Education constitute the main components of SSEE. Drawing on several historical events and facts, the history curriculum informs learners of our historical past by helping them better understand the experiences and changes that people have gone through over time. It uses past experiences to understand and explain the present and plan for the future. The curriculum further provides opportunities for learners to develop and use inquiry skills to explore phenomena in their natural, cultural, and social environment. History, an important component of the SSEE curriculum, also focuses on developing important values and scientific attitudes.

As far as the teaching of history is concerned in Mauritian classrooms-although, Boodhoo (2004: 73) presents the subject as one which aims at stimulating ''the imagination and developing critical thinking in -it has been observed that the teaching of history in schools emphasises more on the memorisation of facts and figures rather than the development of any skills which history teaching should entail. It has also been seen that, rather than allowing the student the opportunity to think about historical events, today's climate of standardised testing encourages the students to memorise historical dates and events. As such, the very purpose for which history finds its place in the school curriculum is defeated. The repercussion of such a practice is observed later when very few students opt for history at School Certificate and Higher School Certificate levels. In Mauritius, the Private Secondary Education Association (PSEA) and the Mauritius Examination Syndicate (MES) hold statistical records showing a dramatic decline in the number of candidates taking history at the School Certificate and Higher School Certificate levels. However, discussing the reasons for the subject's decline is beyond this article's scope.

Pedagogical Practices

Pedagogical Practices can be understood as a set of instructional techniques and strategies for acquiring knowledge, skills, attitudes, and dispositions within a particular social and material context. According to (Kapur, 2018), pedagogical practices are concerned with attempts to initiate reform within the classroom and incorporate technological resources. (Kapur, 2018) further posits that pedagogical practice becomes innovative when teachers employ a range of resources, materials, methods, principles, and explanations to transmit knowledge to the students. In the Mauritian context, all primary schools have been equipped with an interactive whiteboard (IWB) to make teaching and learning appealing to the learners. The ministry of education organises regular training for the teachers in using the interactive whiteboard. The objective is to ensure that all teachers understand effective teaching methods to maximise student learning. However, reluctance on the part of the teacher has been observed in using technology in their teaching, especially when introducing new concepts. Teachers still prefer talk-and-chalk traditional approaches. Technology tools such as IWB are preferred by teachers for revision activities.

Methodology

As the focus of the study was to understand the actual practice that occurs in history classrooms and the pedagogical choices made by the teachers, an interpretivist qualitative methodological approach was deemed most appropriate to listen to teachers' voices. Consequently, a purposive sample comprising fifteen primary school teachers, both novice and experienced, was chosen as the study sample from the four zones on the island. The teaching experience of the selected participants ranged between one and twelve years.

Data for the study was generated through classroom observations followed by an in-depth interview to further explore the observed lessons in the wider context of the primary history curriculum as stipulated in the National Curriculum Framework (NCF, 2015) and as taught and interpreted in the school. I prepared an observation sheet to take note of the strategies and the teaching methods deployed by the teachers in history classrooms. I also noted teacher and student interactions. I considered this aspect important as I believe the way teacher communicates and interacts with students play an important role in students learning. Another area that I regarded as important to observe and the document was teachers' historical knowledge or content knowledge.

Following classroom observations, I recorded semi-structured interviews with the participants with their permission. The purpose of the interview was to get a deeper understanding of their practice adopted in the classroom, highlight their strength, and voice out the challenges encountered in the implementation process. The semi-structured interview thus provided a platform for the teachers to speak candidly about their practices, concerns, and apprehensions in their teaching process.

Being fully aware of the ethical concerns associated with classroom observation, I met the teachers before observing their lessons and briefed them about the purpose and objectives of the study. I also ensured that my presence in the classroom did not cause any disruption in the normal functioning of the classes. Moreover, the transcripts of the interview were sent to the participants for member checks.

Findings

Data gathered from classroom observations and interviews of participants point towards teachers' content knowledge of the subject as a crucial factor in determining the teaching approach and method adopted by the teachers in their classroom practices. For instance, when asked about their content knowledge of the subject, teachers in this study spoke about basing themselves on the knowledge acquired during their professional training course. Some also mentioned doing prior research and reading. However, one teacher said, ''I haven't actually done a lot of reading. I think it's something that develops with experience over time'' in relation to teaching abstract concepts such as slavery, the indentured labour system and settlement long ago. On the other hand, novice teachers expressed concern over the limited content knowledge and mentioned ''restricting their teaching to whatever is prescribed in the textbook''. This is also reflected in the questions posed to students in the class, which were limited to testing basic factual information rather than assessing the skills.

Another important finding emerged from the data focused on teacher preparation which largely determined the interplay between content delivery and the pedagogical choices made by teachers. For instance, one of the teachers mentioned, ''I have to prepare my pupils for examination, and I find making them repeat loudly important events a good way to remember''. Another teacher with an experience of ten years of teaching stated, ''I have limited time and there is a lot to teach. Most of the learners in my class are slow learners. I, therefore, have to adopt this practice of drilling exercise and constant revision if I have to make them ready for examination". Although such kind of teaching may not be in line with the demands of the curriculum, it cannot be denied that teachers show a clear idea about how their pupils learn. Furthermore, findings indicate contextual factors such as time allocated to the subject, student-teacher ratio, and the assessment modality as constraints for history teachers.

Based on the key findings drawn from the study, I present the relationship between the three types of teacher knowledge, that is, knowledge about the subject (history), knowledge about pupils and knowledge of classroom practices, resources, and activities, and secondly, teachers' professionalisation as important features in the quality of teaching that occurs in the primary history classroom..

Discussion

History teacher's knowledge of the subject

At the very outset, the most pertinent questions that deserve attention are: What is it that history teachers need to know to teach history effectively in the classroom? Where and how is this knowledge base developed? Although conceptualising teacher knowledge is a complex issue, a basic answer to the question raised above would be that history teachers need to know a lot of history, and some selection of important dates and events might be a place to start. Moreover, the foundation of the knowledge of teacherseachers' knowledge lies in the subject or content knowledge that the teachers derive from their degree or their engagement with readings. However, considering the Mauritian context, the knowledge base of the history teachers, especially those teaching at the primary level, is not derived from their degree courses. They acquire historical knowledge through modules taken at either certificate or diploma level during their professional training courses. But is the content knowledge acquired during these professional courses sufficient to teach the subject effectively? Teachers who enrol in the diploma courses bring with them a basic knowledge of the subject given that they have studied the subject either at the primary level or the lower secondary level. The importance of subject matter as an essential component of teacher knowledge cannot be belittled. Successful teaching involves a myriad of tasks, such as selecting worthwhile learning activities, giving helpful explanations, asking relevant questions, and assessing students' learning. To a great extent, all the mentioned activities depend on teachers' understanding of the subject content and what the students are to learn (Buchmann, 1984).

From the teachers' accounts, it can be observed that the implications of detailed content knowledge are clear in successful history lessons, especially where teachers use knowledge to ask focused questions, probe students' responses, and correct or explore misconceptions.

This brings us to another very important dimension of the discussion, teacher preparation or professionalisation. Although studies have shown that the quality oflearning that occurs within the classroom depends to a great extent on the learning opportunities created by the teacher (Hattie, 2009; McCaffrey, Lockwood, Koretz, Louis, & Hamilton, 2004), a question that captures attention is how do teachers acquire the knowledge and more specifically in relation to this study, what are the qualities that a teacher must possess and how are these qualities imbued in the teacher to ensure that conducive learning opportunities are created to promote effective learning? Ambe (2006); Burning (2006); Darling-Hammond and Baratz-Snowden (2005); Murphy et al. (2004); Wise and Leibraid (2000) have stressed the role of teacher educators in preparing effective and proficient teachers and conclude that student learning depends largely on how teachers are prepared and supported. Moreover, it is argued that professional training enhances the knowledge, skills, and attitudes of teachers so that they, in turn, improve the learning experiences of students.

In the Mauritian context, all primary teachers undergo a Teachers' Diploma training before embarking on their careers as full-fledged primary school teachers. Teachers are offered courses in both subject content and pedagogy during their training. With reference to the teaching of history, teachers are required to take two modules, one that prepares them with the content knowledge and the second module, which deals with the teaching of the content learned. However, with the recent review of the Teachers Diploma Programme (TDP Programme handbook, 2014), there has been a decrease in the time allocated to subject content because the teachers can develop content knowledge through their reading. The repercussion of such a decision is seen in the performance of trainee teachers in their examinations. A few trainee teachers mentioned that they are ''overwhelmed with the amount of information required to assimilate in a module of fifteen hours''. Such a situation is a matter of concern as these teachers have a basic knowledge of the history taught in classrooms. The above discussion emphasises two pertinent points: the content knowledge of the teacher and the quality of teacher preparation. While teacher content knowledge is certainly a component of teacher professionalism, it is also to be noted that professional competence involves more than just knowledge. The other factors contributing to mastery of teaching and learning include skills, attitudes, and teacher motivation (Blomeke & Delaney, 2012). The factors mentioned above derive from the pedagogical content knowledge model (PCK) initially proposed by Shulman (1986), who saw it as a mechanism for connecting distinct bodies of knowledge for teaching. He described it as ''representing the blending of content and pedagogy into an understanding of how particular topics, problems, or issues are organised, represented, and adapted to the diverse interests and abilities of learners, and presented for instructions'' (Shulman, 1986: 8). PCK requires teachers to use analogies, illustrations, examples, explanations, and demonstrations as channels for their subject knowledge to engage and enthuse pupils. For instance, the primary teachers in this study demonstrated their awareness of a wide repertoire of teaching strategies they had become familiar with during their professional training course. However, while the experienced teachers showed their knowledge and ability to navigate through the different history lessons using examples beyond the available resources, the less experienced restricted themselves to the activities in the textbook.

Studies since 1986 have also suggested the complex relationships between subject knowledge and pedagogic knowledge (Wilson & Wineburg, 1988; Turner-Bisset, 1999; Brown et al., 1999). Shulman's model of pedagogic content knowledge provides a way of relating subject-matter knowledge to pedagogic knowledge. And therefore, it can be argued that although detailed content knowledge is a characteristic of successful teaching, it is not sufficient. It is to be noted that expert teachers deploy both content knowledge and pedagogic content knowledge in planning their lessons and putting the same into action. In the same way, it can be said that teachers' knowledge of history is not defined by their knowledge of the historical past alone. Moreover, the classes observed by the history teachers' have shown that their content knowledge is almost certainly too limited for the classroom. Furthermore, as the demands of the curriculum are diverse, history teachers, at some time or the other, need to build up new knowledge about unfamiliar topics.

Teachers' knowledge of pupils

Although it is difficult to mount an argument against the proposition that teachers should know the subject they teach and must be intellectually capable and well-informed, it is argued that teachers also need to be able to relate to their pupils. This second dimension of history teachers' knowledge related to pupil learning can be understood in two ways: first, teacher knowledge about how pupils learn in general, and second how students develop an understanding of history. Furthermore, knowing the pupils allows teachers to work better with demotivated or less able learners. It is contended here that knowing the subject content might be less important than the ability of the teacher to communicate, understand learners, and make learning real. Moreover, it's been argued that one might know ''too much'', but good teaching needs a ''clear, coherent overview'' (Shemilt, 2009: 144). Foster (2008) also emphasises the importance of teachers' ability to provide pupils with an overarching 'map of the past' rather than a mere acquaintance with details.

It was noted during the observations of the teachers' classes that they all developed their way of learning and teaching in the classroom. However, their ability to clarify the information may not necessarily be linked to the sophistication of their understanding. The teachers developed practical knowledge about how pupils engage with the historical material and how they process, store, and deploy what they have learned. It is to be noted that understanding learners concerning the traits mentioned above shapes the way teachers teach. Research (Shemilt, 2009) has shown that one of the most important developments in history classrooms in the last few decades, especially in the countries in the West, has been a movement away from largely transmission-based approaches in which pupils were assumed to be 'empty vessels to be filled with knowledge towards social constructivists models of learning in which pupils engage actively with learning through discussion and peer learning. This kind of learning, however, contrasts with what occurs mostly in Mauritian history classrooms. Rote learning and drilling still appeared to be common practices.

Teachers' knowledge of resources

The third dimension of history teachers' practice relates to their knowledge of resources and approaches. It is to be noted that history lessons in twenty-first-century classrooms have become resource-rich. Various visuals and interactive resources are available for the teachers to support learning. However, it must be remembered that the most important resource in any classroom remains the teacher. Even today, most history classrooms exhibit the traditional transmission model where teachers explain the content, ask questions, further probe pupils' understanding of the lesson, correct errors, and assess pupils' progress. It has already been seen that in discharging these different activities, teachers draw on their knowledge ofhistory and pupils, but they also draw on their knowledge of when and how to deploy themselves as a resource. The point raised here is that resources and the classroom activities teachers support constitute an arena for deploying teacher knowledge.

Nevertheless, it has been noted that in Mauritian classrooms, there is a heavy reliance by the teachers on traditional resources such as textbooks. Teachers limit themselves to the information and activities provided in the textbooks. One teacher mentioned that the ''teacher's resource book should provide all the answers to support them in their teaching teaching''. Such teachers' beliefs are contrary to the general understanding and practices, especially in developed countries such as the UK and USA. Teachers in these countries demonstrate knowledge in the history classroom with confidence about when and what resources to use, which is not simply a situational skill but demands knowledge about the range of resources teachers are a part of.

In Mauritian classrooms, as far as innovation and resources are concerned, all primary schools are equipped with an interactive whiteboard. Subject-specific resources have been prepared and provided to the teachers. However, observation of the history teachers' classrooms revealed that not all of them appeared confident with using the interactive whiteboard. A few teachers used it as a tool for revision. They also mentioned that ''if they could be provided with new resources as the pupils already know all the answers of the activities they are using''. Such teacher requests show their dependency on others, even for their teaching in class.

I have framed the above discussion about teachers' classroom knowledge regarding resources and activities because this is how teachers describe their practice. Although teachers' descriptions of their practice are often implied in terms of activities, what is clear is the profound understanding of pedagogy underlying these.

Conclusion

The study began with a simple proposition about subject knowledge in teaching, but teachers' knowledge is more complex. Literature also refers to many features that characterise expert teachers, which include pedagogical content knowledge, problem-solving skills, addressing the needs of diverse learners, decision-making, awareness of classroom events, greater understanding of the context, and respect for students.

In this study, three dimensions of teachers' knowledge have been explored. It can also be noted that these three are not separate: they are interrelated and draw from each other. It is to be noted that learning to teach involves the acquisition of diverse knowledge. It refers to the school and the classroom as the critical site for acquiring learning. History teachers must make active connections between their content knowledge and other knowledge they need to deploy to work successfully. Much of teachers' expertise and knowledge is grounded in classrooms and classroom practice, which suggests that classrooms are the most effective site for developing knowledge and expertise.

To conclude, the importance of the subject content knowledge that teachers hold is important. Still, in addition to assimilating academic knowledge, teachers must incorporate knowledge derived from experiential and practical experiences in the classroom. Responses of the teachers interviewed showed that the experienced teachers developed their understanding of the subject and devised ways of teaching. Furthermore, history teachers need to balance basic and disciplinary knowledge and sustain learners' interest by engaging in interactions about the content choices available to them.

References

Ambe, EB 2006. Fostering multicultural appreciation in pre-service teachers through multicultural curricular transformation (Electronic version). Teaching and Teacher Education, 22(6):690-699. [ Links ]

Berg, CW 2019. Why study history? An examination of undergraduate students' notions and perceptions about history. Historical Encounters: A journal of historical consciousness, historical cultures, and history education, 6(1):54-71. [ Links ]

Bentley, JH 2007. Why study world history? World History Connected, 5(1). Available at: http://worldhistoryconnected.press.uillinois.edu/5.1/bentley.html [ Links ]

Blomeke, S & Delaney, S 2012. Assessment of teacher knowledge across countries: A review of the state of research. ZDM Mathematics Education, 44:223-247. [ Links ]

Boodhoo, R 2004. Teaching history at primary. Journal of Education, Mauritius Institute of Education. (Reduit: Mauritius), 3(1):68-78. [ Links ]

Brown, T, McNamara, O, Hanley, U & Jones, L. 1999. 'Primary student teachers' understanding of mathematics and its teaching', British Educational Research Journal, 25(3):299-322. [ Links ]

Buchmann, M 1984. The priority of knowledge and understanding in teaching. In J Raths & L Katz (eds.), Advances in teacher education (Vol.1, pp. 29-48). Norwood, NJ: Ablex. [ Links ]

Burning, M 2006. Infusing facets of quality into teacher education. Childhood Education, 82(4): 226. Retrieved from Academic Search Premier. [ Links ]

Cochran-Smith, M & Zeichner, KM 2005. Studying teacher education: the report of the AERA panel on research and teacher education. American Educational Research Association: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., 329. [ Links ]

Darling-Hammond, L & Baratz-Snowden, J (eds.) 2005. A good Teacher in every classroom: Preparing the highly qualified teachers our children deserve. San Francisco, CA:John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Foster, S 2008. Usable Historical Pasts: A Study of Students' Frameworks of the Pasts: Full Research Report, ESRC End of Award Report, RES-000-22-1676. Swindon: ESR. [ Links ]

Fumat, Y 1997. History, civics, and national consciousness. Citizenship, Social and Economics Education, 2(3):158-166. [ Links ]

Hattie, J 2009. Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. London, England: Routledge. [ Links ]

Haydn, T 2012. History in schools and the problem of "The Nation". Education Sciences. 2(4):276-289; Available at: doi:10.3390/educsci2040276 [ Links ]

Jorn, R 2005. History: Narration Interpretation Orientation. New York: Berghahn Books. [ Links ]

Kapur, R 2018. Pedagogical Practices. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323794548_Pedagogical_Practices Accessed on 4 April 2022. [ Links ]

Leinhardt, G, quoted in Wineburg, S 2001. Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts, Philadelphia: Temple Press. [ Links ]

MacMillan, M 2009. The Uses and Abuses of History. Random House: New York, NY, USA. [ Links ]

McCully, GE 1978. History begins at home. The History Teacher, 11(4):497-507. [ Links ]

McKinseys 2007 How the World's Best School Systems Come Out on Top. London & New York. [ Links ]

Ministry of Education and Human Resources, Tertiary education and Scientific Research 2009. National Curriculum Framework - Republic of Mauritius. [ Links ]

Ministry of Education and Human Resources, Tertiary education and Scientific Research 2015. National Curriculum Framework - Nine Year Continuous Basic Education, Grades 1 to 6. The Republic of Mauritius. [ Links ]

Ministry of Education and Human Resources, Tertiary Education and Scientific Research 2016. National Curriculum Framework Nine-Year Continuous Basic Education Grades 7, 8 & 9 . the Republic of Mauritius. [ Links ]

Movement for change 2009 - new curriculum and textbooks 2013 to 2015. MIE vs others. The battle of the publishers? v/s quality. The problem of individual v/s institutional control [ Links ]

Murphy, PK, Delli, LAM, & Edwards, MN 2004. The good teacher and good teaching: Comparing beliefs of second-grade students, pre-service teachers, and in-service teachers (Electronic version). The Journal of Experimental Education 72(2):69-92. [ Links ]

Namamba, A & Rao, C 2017. Teaching and Learning of History in Secondary Schools: History Teachers' Perceptions and Experiences in Kigoma Region, Tanzania. European Journal of Education Studies, 3(2):172-195. Available at: doi: 10.5281/zenodo.290606 [ Links ]

New Social studies Textbooks for secondary Form 3 1986. Controversy over teaching of history - document-based v/s storytelling approach. [ Links ]

Shemilt, D 2009. 'Drinking an ocean and pissing a cupful: how adolescents make sense of history', In: L Symcox, & A Wilschut (eds.), National History Standards: The Problem of the Canon and the Future of Teaching History. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing. [ Links ]

Shulman, L 1986. Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2):4-14. [ Links ]

Stearns, PN 1993. Meaning over memory: recasting the teaching of history and culture. Chapel University of North Carolina Press. [ Links ]

Stearns, PN 1998. Why study history? American Historical Association. Available at: http://www.historians.org/about-aha-and-membership/aha-history-andarchives/archives/why-study-history. [ Links ]

Stricker, F 1992. Why history? Thinking about the uses of the past. The History Teacher, 25(3):293-312. [ Links ]

Teacher's Diploma primary 2014. Programme Handbook. Mauritius Institute of Education. Reduit, Mauritius. [ Links ]

Turner-Bisset, R 1999. The knowledge bases of the expert teacher. British Educational Research Journal, 25(1):39-55. [ Links ]

Westhoff, LM & Polman, J 2007. Developing pre-service teachers' pedagogical content knowledge about historical thinking. International Journal of Social Education, 22(2):1-28. [ Links ]

Wilson, SM & Wineberg, SS 1988. Peering at history through different lenses: the role of the disciplinary perspectives in teaching history, Harvard Educational Review, 89(4):527-539. [ Links ]

Wise, AE & Leibrand,JA 2000. Standards and teacher quality: Entering the new millennium (Electronic version). Phi Delta Kappan, 81(8):612-621. [ Links ]