Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Yesterday and Today

On-line version ISSN 2309-9003

Print version ISSN 2223-0386

Y&T n.28 Vanderbijlpark Dec. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2223-0386/2022/n28a1

The Pandemic History Classroom: grouping or groping the digital divide

Karen HarrisI; Tinashe NyamundaII

IDepartment of Historical and Heritage Studies, University of Pretoria, South Africa; Orcid: 0000-0002-9246-5950; karen.harris@up.ac.za

IIDepartment of Historical and Heritage Studies, University of Pretoria, South Africa; Orcid: 0000-0001-9624-762X; tinashe.nyamunda@up.ac.za

ABSTRACT

This article is concerned with the impact of Covid-19 on the higher education sector. It examines the impact of group work in the discipline ofhistory in remote university teaching and learning set in the context of Covid-19 imposed lockdowns in South Africa. When the pandemic broke out, few were prepared for its worst excesses in terms of lives lost impact on health facilities, economies and higher education. Lockdowns to limit the pandemic's spread were imposed in many countries worldwide, limiting in-person interaction, which affected various aspects of human contact, not least in university education. Taken away from campuses, universities in South Africa, as elsewhere, were forced not only to adapt to online teaching but to be inventive in the methods used to retain student participation and engagement. While technology was heralded as the solution to the global crisis in teaching, other concerns affect the well-being of students that also require attention. By using the research conducted with staff and students in history modules at one South African university, this article considers the pandemic classroom with its online and remote mode of instruction. It takes specific cognisance of what is lost due to this form of engagement in terms of isolation's psychological and emotional impact on students in the tertiary education sector. Within this context, it assesses whether the use of group work within a university environment and, in particular, the discipline of history, is a possible means to try and bridge this digital divide or if this option is merely a case of groping in the digital ditch.

Keywords: Group work; Higher education; History module; Covid pandemic; Online learning; Peer learning.

Introduction

The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on higher education has been profound. While for many, it has been heralded positively as a time to rethink and recalibrate the sector, if not dramatically transform it1, some argue that countless unknown repercussions and dire consequences will only be fully realised in the long term when the implications become more apparent2. Before the pandemic, much scholarship on higher education was generally concerned with access issues, the implications of massification and quality in South Africa, as elsewhere on the continent3. But with the pandemic outbreak, these concerns shifted towards how to make university education continue in the wake of national, not least campus, lockdowns. Questions rested on how to save the academic year and how to adapt to remote learning as a way of sustaining university education4. In this context, the online classroom emerged, termed the "pandemic classroom" in this article. While questions of access, massification and quality of higher education loom large and are of great concern, this article considers the pandemic classroom, which has resulted from the restrictions imposed by the global spread of the coronavirus. It utilises the case study of one discipline, history, to assess the impact of group work conducted under conditions of remote learning. In some ways, it is hoped that the focus on remote learning as an option and group work as a teaching tool may also speak to some of the broader research concerns of access and quality. This is also relevant in the post-pandemic period, given what is being perceived as the benefits of the online and hybrid flexible mode of higher education delivery for the future,5 which we argue are not so beneficial.

There have been a plethora of commentaries, surveys undertaken, and articles published both in the popular and academic domain on the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on higher education across continents.6 This has essentially been dominated by assessing its successes and failures or focusing on various technologies, models and connectivity concerns.7 While quantitative statistics and numbers seem to dominate much of the research on the impact of the pandemic, some studies have also taken on a qualitative approach highlighting the psychological and emotional impact of isolation and remote learning on students in the tertiary education sector.8 A key concern in the latter research is what D Burns, N Dagnall and M Holt, refer to as the "psychosocial impact of the global Covid-19 outbreak", honing in on the concept of well-being.9 Within this context, they highlight the importance of "social connections" for university students and how even under the pre-Covid situation, research had shown how students suffered from loneliness and "feelings of disconnectedness", which were linked to "stress, anxiety and depression". 10The latter is also flagged in the research by Y Zhai and X Du on collegiate "mental health".11In both these studies emanating from the East and West, there is a recommendation that in the Covid and post-Covid environment, universities will need to reconsider how they implement well-being initiatives in the future.12 Focusing on the lack of group work and collaborative projects for students mentioned in the work by Burns et al. calls for greater attention,13 not only in a general sense but within the context of specific disciplines. It is to this dimension of student well-being and the role of group work and peer interaction that this article turns to the face of the "pandemic classroom". It focuses on the impact and the teaching of history at the tertiary level.

The Pandemic classroom

The modern research university is essentially seen as an institution that produces new knowledge passed onto the student body.14 However, according to R Danisch, this is not all they should do. The late nineteenth-century focus on "knowing that" (episteme) has transformed to "knowing how" (techne) so that an abstract body of theoretical knowledge can be applied to execute specific tasks. The university also possesses various roles within its structure that generate a distinctive culture and mission.15 The university environment also plays a role as a "future-shaper" of students and is a platform for cultural, social and economic change.16 However, the shift to the pandemic classroom has altered this aspect of university learning. It has taken many students from campuses, away from other students, libraries, lecture rooms, common rooms and other communal spaces. It has turned the university from being a physical space into a digital one. Instead of having student peers, those confined to the home environment have to confront family members daily and convert those living spaces into university learning spaces, a factor whose effects are yet to be fully explored. In that context, the digital pandemic classroom is not limited to considerations of the coronavirus but considers the pandemic of personal and social disconnection. Where students learned through interaction how to effectively collaborate, get involved in student debate, learn to be responsible for their finances and shape their values as they transitioned into adulthood, being home significantly substituted all of these experiences in unimaginable and often unintended ways.

It is an accepted belief that tertiary education should go beyond the mere dissemination and reception of knowledge presented by a lecturer and received by a body of students. The lecture hall and the university landscape, and all this entails, contribute to the graduate's holistic development and attributes. Going to university is in itself a rite of passage, and it is here that the graduate is moulded, tempered and prepared for the world of work and social life. One of the critical components of this experience is the students' fellow students- their peers. We argue that this peer interaction is multi-layered and takes on many forms: peer-learning, peer-pressure, peer-empathy, peer-modelling, peer-encouragement, and many more.

G Krull and D de Klerk note that distance online learning is nothing new.17 But in a South African context, this was limited to only those universities, such as the University of South Africa (UNISA), designed for this and usually accommodate more mature students who are employed and part-time learners.18 Emerging debates are pitted between those in favour of and those against online learning. Those in favour, for example, Krull and de Klerk, argue that online learning is the future despite challenges. Those against, for example, N Marongwe and R Gadzirai point to epistemic inequalities in higher education that the digital divide can only widen. Many scholars use generalised studies and broad statistics to make their point. This article, however, uses a micro-level study of one university subject- history-to make a point of the effects of moving to an online classroom under pandemic conditions to test the use of a group work teaching tool as a way of determining what extent the shift has groped, or grouped the digital divide. In this case, grouping [the digital divide] is putting people into groups to work together, whereas groping refers to a move towards something you cannot see or are uncertain of.

According to the International Association of Universities (IAU), Covid-19 instigated a sudden shift to online teaching to respond to the need to continue teaching activities and to motivate students when social distancing measures were in place.19 Africa, which had the lowest transference to distance teaching, still featured a 29% transition, while Europe had an 85% transference.20 These institutions created a "pandemic classroom" devoid of all the peer-learning mentioned above and engaging features and critical peer attributes. Some students surveyed for this research complained that learning was often reduced to a lecturer's voice or PowerPoint lecture on a black computer screen. More often than not, unless a lecturer asked students to turn on their cameras briefly, you would never see any other student's faces. In any case, in large classes, it was not feasible to keep videos on because of bandwidth and connectivity considerations. In the end, for some lecturers and students, digital learning became a fixture to be fulfilled and not necessarily an exercise to look forward to. As one history student noted in the survey undertaken for this study, one could be in a virtual class of 300 people and still be alone.

Moreover, several other history students indicated that they lost the motivation to participate in class discussions and debates with fellow students as it was like speaking in a void. History lecturers interviewed found that they lost the ability to use illustrative gestures, write on the board, read and respond to student expressions and establish spontaneous connections that only in-person teaching can provide. This, we argue, is particularly relevant in the history classroom, where contentious issues, debatable views and differing opinions are integral to teaching the subject.

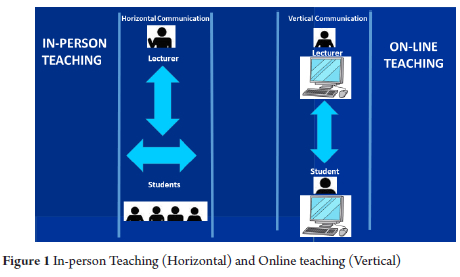

Danisch argues that Covid-19 has "made it easier to reduce teaching to knowledge dissemination and to obscure other, equally important, forms of education that help students to be better citizens, thinkers, writers and collaborators".21 All four of these forms of education resonate specifically with the history curriculum and skills that the history lecturer strives to inculcate to varying degrees. The transition was from in-person teaching, which we describe as a horizontal form of communication - from lecturer to students and students to students - to be replaced with what can be described as a vertical form of teaching - from lecturer to student. (See Figure 1)

Within this linear and isolated domain, the pandemic classroom, we assess the role of group work among history students. Given all of the digital limitations described above, several lecturers in the history department used for this study opted to use group work to try and re-engage students and provide some form of academic fellowship and student connectedness. They hoped that their various approaches to group work in the modules they taught at different year levels would help to stimulate digital connections and group the divide. That way, some students would get to meet, even if virtually, and be in a position to gain some of the kinds of interactions lost with the shift to the pandemic classroom. Foregrounded by a brief historicisation and discussion of what group work entails, what follows examines the effects of the attempts to group the digital divide within the domain of the discipline of history.

Group work

Group work as a form of teaching dates back to the very start of human history22 when elders and teachers would engage members of their societies and peers would enhance the learning experience. Examples are apparent among the ancient Greeks, with instances of elders teaching select groups of learners.23 In contrast, group learning was prevalent amongst pre-colonial African societies, with young men or women coming under the tutelage of elderly kin members to impart different skills useful for members of the communities where they came from.24 The late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries saw the use of group work by evangelical Christians as a teaching method, given the poor social conditions of the time.25 Subsequently, the more formal and structured use of collaborative projects emerged in the latter half of the twentieth century transforming from an initial focus on the periphery of main school education to being an integral component across the primary, secondary and tertiary spectrum. Group work, also known as "collaborative and cooperative learning", became a mainstay of many university courses and developed its pedagogy.26 It was lauded for its advantages: communication skills, social skills (diversity), problem-solving, critical thinking, self-management skills, and interpersonal relations.27But it was also critiqued and derided by educators and learners alike as an easy means to lessen the marking load of modules with high enrolment figures28 -an apparent issue with essay-writing subjects such as history. Students also criticised it as not being a fair form of assessment. This is not without precedence and persists today. Some lecturers who manage substantial student numbers may find it easier to lessen the marking pressure by utilising this approach more than individual self-assessments. In some instances, some university administrations appear to care more about output and throughput numbers than the quality of the graduates being produced and therefore do not question these approaches. There have been recent cases in which the quality of students produced under some of South Africa's leading distance education institutions has come under the spotlight.

29However, published research on how history classes within a higher education system have utilised group work as a learning tool, particularly within the large lecture context, remains relatively under-researched if not researched.

Despite some negative connotations about group work, its usefulness is not in doubt if deployed as part of the arsenal of different assessment tools. In explaining social interdependence theory, DW Johnson and RT Johnson claim that working cooperatively with peers and valuing cooperation results in "greater psychological health than does compete with peers or working independently'.30 They also claim that working cooperatively as opposed to individualistically or competitively results in:

• a willingness to take on difficult tasks and persist

• a higher-level reasoning, critical thinking and metacognitive thought

• a transfer of learning from one situation to another

• a positive attitude to the tasks being completed31

In line with this positive view, ME Pritchard and GS Wilson assert that "the development of interpersonal relationships with peers is critically important for student success".32

Yet the restrictive regulations brought on by the pandemic challenged and reduced the opportunities for students to associate and work with fellow students physically.33 The pandemic classroom-the learning environment they had to create for themselves away from campus-removed them from interaction with fellow students and lecturers both inside and outside the lecture hall. At a very elementary level, the closure of university campuses and the introduction of various levels of lockdown resulted in an overwhelming sense of isolation. The impact of losing the opportunity to confer with fellow students, listen to other students' questions, or even copy notes amongst other ordinary and everyday activities is often not considered.34 This is an important element of collective studentivism, which forms an important part of the psyche of being a student at a university. It has been argued that peer influence can be used to reinforce learning, and in certain cases, peers, more than teachers or lecturers, can inspire deep learning.

This relates directly to positive psychology and one of the tenets of M Seligman's PERMA model, which highlights the importance of possessing and nurturing meaningful relationships with others to reduce the risk of isolation.35 This is unlike the pandemic classroom, which often amounts to staring at a computer confined to one's room at home if the student is privileged enough to have their room. Some, who may stay in rural areas or informal settlements, have had to make do with attempting to attend online lectures in a room full of people or have had to wait until others are asleep to download recorded lectures, depending on data or network availability.36 Moreover, in contrast to this isolated situation, evidence suggests "that active-learning or student-centred approaches result in better learning outcomes than passive-learning or instructor-centred approaches, both in-person and online".37 Constructivist learning theories also argue that students must actively participate in creating their learning. 38

It is to these two components that this research turns: into the isolation of the university student within the Covid-19 context and the utilisation of group work as a possible means to partially address this divide. In light of the absence of this critical form of interaction with peers, this article assesses whether the introduction and use of group work in history teaching within this remote online situation can somehow bridge the digital divide between peers. This research assessed its usage in the context of the pandemic and online remote learning within a university environment and looked specifically at the discipline of history.

Method and Rationale

In what follows, we detail the accounts of the group work experiences of undergraduate students enrolled for history modules at a tertiary institution in South Africa. The summary details experiences with group work at the first, second and third-year levels. The research on which this article deliberates includes three categories of undergraduate students at University within the discipline of history with varying in-person and remote learning experiences for the period 2019-2021:

• first-year students who have only had remote teaching

• second-year students who have had six weeks of in-person teaching and over a year of remote teaching

• third-year students that have had one year and six weeks of in-person teaching and over a year of remote teaching

While the different forms of group work introduced at the various levels are considered, the main focus is on how the students experienced this interaction. In other words, does group work bridge the digital divide, or are we merely groping in the digital ditch? It must be noted here that the way group work was done before the pandemic and during it had to be adjusted. For example, K Brzezicki's discussion of the implications of group work in a history classroom examined the role of projects, descriptions, observations and face-to-face discussions and how to moderate all of these. He gives particular learning strategies that would stimulate participation.39 But as a recent five-part series on online discussions have revealed, students on a blank screen in diverse locations and who can easily switch off have to be approached differently. The study provided numerous tips such as role play, jigsaw, case study, and round robin, among others, to attract and retain the attention of these students in a remote learning and group discussion context.40 However, the lecturers whose modules were surveyed for this study were free to choose what they felt worked best for their specific modules, themselves, and their students.

We used quantitative and qualitative questions to determine group work's impact on students. We were particularly interested in six specific questions-five quantitative and one qualitative-from a survey sent out on a university module feedback platform to the students. The questions were as follows:

Quantitative

1. The group work was well organised by the lecturer.

2. Group work is not a fair way to assess my ability.

3. The group work project made me feel less isolated within the context of remote learning.

4. I prefer to do assignment work on my own.

5. I enjoyed the group work as I was able to connect with my peers, and we kept in touch after the project.

For each of the quantitative questions, there were five responses in the following order:

1. (1) I strongly disagree.

2. (2) I disagree.

3. (3) Neither agree nor disagree.

4. (4) I agree.

5. (5) I absolutely agree.

Qualitative

6. How do you feel about group work, and did it contribute to peer learning? (Did you like/ dislike and your reasons/suggestions for changes to the format of group work.)

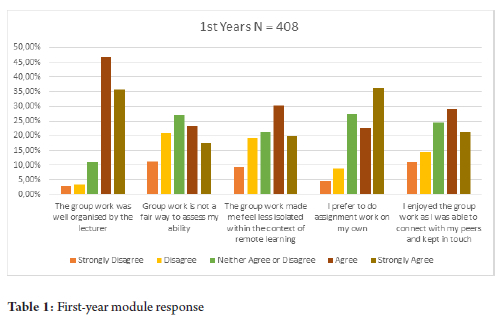

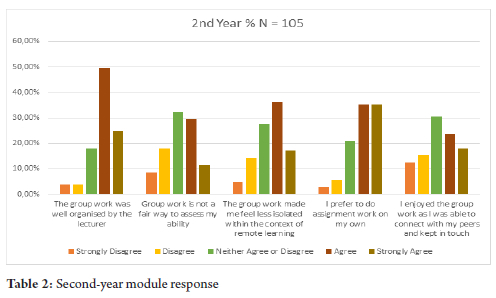

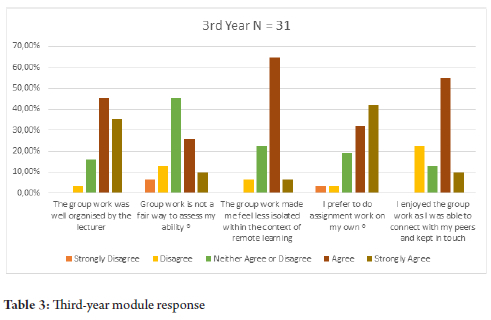

The software tabulated both answers' frequencies and provided percentages to measure the level of satisfaction with the group in each category of question asked. But the tables were further compressed into three comparative tables for each year in the undergraduate program. (See Tables 1 - 3)

Using the findings, the study examined the efficacy of group work under Covid-19 imposed remote teaching and learning. It examined the different varieties of group work and its effect on students studying history from first to third-year levels. But the study must not be regarded as a testament to the benefits of distance education. Indeed, the fact that less than half of the history students responded to the online survey reveals the extent to which students can either be disengaged or feel online fatigue. Had this survey been conducted in class with students on campus, we are confident that a significantly larger proportion would have participated. So, the results reflect the responses of only those history students who participated in the survey. We maintain that in-person teaching and on-site university experience are invaluable and necessary as part of the development of the holistic university student. As such, we are only looking at group work in the context of a crisis, of how effective it may or may not be as a way of at least grouping the divide caused by isolation and distance imposed by online learning. We are also not looking at group work as the most effective teaching and assessment method, as this is much debated, but what role it contributes toward optimum learning as part of other methods and approaches within the context of the pandemic restrictions.

In examining group work as part of the online teaching and learning toolkit, we were sensitive to several factors, such as the already mentioned space for academic freedom in deciding approaches and assessment methods amongst lecturers in their history modules. They considered the students' capacity to discern, engage, and comprehend the material at each stage. We also considered that all these students had very different experiences with higher education. For example, third-year students would have started university before the outbreak of Covid-19 and the imposition of various levels of lockdown. As such, they would have met and interacted with their lecturers, classmates and others in the university community and within the university's physical environment. They would have had the opportunity to participate in campus activities and had all sorts of in-person experiences that accompany becoming a university student. But, more importantly, they would have experienced contact learning. However difficult the shift to online learning may have been, at least they had some knowledge of their lecturers and classmates from their first and part of their second year against which they could compare.

On the other hand, second-year students would have briefly enjoyed the in-person experience for a couple of months before the imposition of the lockdown and the shift to online learning. But for all their limited interaction with university life, it was more than one can say for the current first-year students. They would generally never have met their lecturers' classmates and enjoyed the university experience, campus landscape, and what it offers. For them, teaching and learning, as well as being a university student, has been significantly reconfigured.

These different experiences attracted our attention to the importance of peer learning. While uploading teaching material, assessments, and live or recorded lectures on a virtual platform gives the impression that something is taking place, the students remain and operate in isolated silos. These experiences are significantly divided along various categories of class, race, and ethnicity, among others, all of which informs or are informed by questions of access and, therefore, quality. In this context, contrary to some suggestions that online learning has been the "great leveller", it has deepened the inequality divide. Some students either had no devices or were disadvantaged by using cell phones instead of laptops or desktop computers. Others had limited or no data, and even in instances where it was supplied, may not have electricity or faced connectivity issues. Yet others live in contexts where domestic chores, which they would have been spared were they on-campus, became a daily obligation that disrupted either class attendance or interfered with their study time. Any of these and other possibilities all conspired to work in different ways against the capacity of students to attend classes or study.

Despite these challenges, group work, with all its limitations, possibly provided one opportunity to bridge this divide in the context of virtual learning. Because of obligations to peers, it invited the participation and commitment of other students, even sometimes working as an excuse for domestic choirs and other family obligations. It also provided the platform to engage in class work seriously. Despite the challenges, as the study will reveal, it allowed students to engage within their diverse remote learning experiences and backgrounds. In what follows, we explore the possible advantages of group work in the conceptual divide, while group learning activities give some semblance of being in, even if not at university

Group work and university learning: Lecturer and student experiences

Group work: First Year

In the first-year history module, group work assignments for the cohort of some 900 students were arranged through tutorial groups. At this level, group work was invaluable in providing a platform for students to meet their classmates even as they were still trying to come to terms with new learning experiences arising from the demands of tertiary as opposed to secondary education. The tutors divided the students into groups of about four to five each, and they were assigned a group assignment topic. Here also, it must be noted that the tutors had to adjust their engagements to suit the challenges of engaging students they had never met and attracting and keeping their attention and enthusiasm in a virtual classroom setup. The tutors guided students and helped them decide how, in their groups, they would "meet up" in terms of virtual connection ( Zoom, Blackboard, WhatsApp group calls) and how often they would communicate.

Once the groups were set up and the interactions began on a particular historical topic, there were numerous complaints about non-compliance because they could not contact each other. At the same time, some students ended up working alone because some group members did not connect or turn up online to participate. Even if complaints about group members not participating or even turning up are unsurprising, the online setup and other background challenges exacerbated the problem. These complaints were generally in the minority of cases, amounting to 15% at most. While numerous other assessments, such as self-marking quizzes, weekly logs and individual assignments, group work proved invaluable in bringing the students to work as a community. This was especially important under lockdown conditions where the students in this first-year level had never actually met each other physically. They got to know each other's names and characters in these group settings. In some instances of students staying off-campus but within the vicinity of the university, they even arranged meet-ups when lockdown regulations were relaxed to lessen isolation and get to know each other and work together on the history group work project, even if they were not allowed on campus. This helped with peer learning and provided opportunities to engage with each other, debate and devise a solution for their history project, and get to know their university colleagues in the context of virtual learning. However, much was lost from the lack of actual in-person contact. Group work allowed for some form of fellowship and created a sense of university and module belonging amongst the students.

As is evident in the above graph, 408 out of 910 students (45%) registered for the history module participated in the survey. Although we cannot speculate exactly why less than half the students participated, the reluctance may likely be explained by students opting not to take up yet another exercise under demanding online conditions-so-called screen or survey fatigue. So, this survey does not necessarily claim to be absolutely representative of the student's views about group work in history, but at least of those who participated. In other ways also, these statistics show that with all the limitations of online learning, group work provides an apparent positive reprieve. Students were divided into groups of between five to six. They were given the choice of three topics, with the primary and secondary source material being uploaded to answer a particular debatable question requiring an opinion and substantiation.

The lecturers appeared to have made the best of the group work opportunities as 83% (strongly agree and agree) of the surveyed students attested to this positively. Even though a modest 33% (strongly agree and agree) indicated that group work was a fair way to be assessed, 50% (strongly agree and agree) concluded that group work made them feel less isolated in remote learning. Sixty-three per cent (strongly agree and agree) of students chose individual history assignments as their preferred assessment. Still, some 50% (strongly agree and agree) were pleased that group work allowed them to experience peer collaboration and keep in touch with other students. It is safe to conclude that under lockdown conditions. Despite students' preference for individual history assignments, they generally appreciated the advantages group work provided in connecting them with their classmates. A sizeable number of students, albeit less than those who approved, stood on the fence, leaving only a minority who disapproved of group work in their history module. While individual history assignments were preferred for their capacity to assess students' performance without the influence of others, group work remained an important option for both lecturers and students alike.

Group Work: Second Year

The group work assignment for 331 students in the second-year history module was fashioned around debates. The students were divided into groups of ten each, and each week, two groups would be given a historical topic and questions to debate on. Group members were expected to read links to journal articles or book chapters as part of the preparation and then "meet up" virtually to discuss their approach, strategy and arguments. But because of connectivity issues, the responses were not verbal, but a link they could type into was provided, and a thread that could easily be followed was created. This allowed the students to type in their answers and make the necessary scholarly references where necessary. This exercise was invaluable, despite some limitations, in creating group cohesion and a sense of community which encouraged them to work well together to try and attain a high collective mark. The group work was designed to allow students to work together because they were decentralised and isolated and to encourage collaboration and critical engagement.

The lecturer found the group work experience useful as it helped students engage and work together, especially those who would not ordinarily do so. The lecturer deployed a Blackboard feature that randomised the group members, which allowed for a certain degree of indiscriminate diversity and clustered students who would not ordinarily work together. The group context also proved an inspiration to struggling students. If groups did well, those who had underperformed individually were inspired to pull their weight and work harder together for the next debate. It was, to a greater degree, a beneficial process in the end.

The students appeared to have enjoyed the process as they were actively engaged. Group work promotes collaborative learning and cooperation in all formative assessments. The idea of swim or sink reduces the competition between peers and promotes cooperation, which is an important part of the learning process. Although the debate is about trying to win a competition, in a group context, it promotes collaboration. This was done by using diverse groups and controversial topics, helping them to be more open-minded even if they were critical. There were cases where some students had to be called out for unruly lack of etiquette, but this was part of the learning process. It allowed the students to think outside the box and work with different groups of people while they were prevented from a normal classroom.

Thirty-one per cent (105 out of 331) participated in this survey. This ratio of students who participated in the second year was less than that of the first year. Just as in the case of the first years, there may be a sense of apathy towards surveys and the extra work it entails, only providing researchers with the perspectives of those who participated. To what extent this can be extrapolated to represent a general view remains unclear. Still, the data was revealing in ways that may offer some general feeling about the efficacy of group work.

Regarding how well the group work debates were organised, 75% of those surveyed approved (agree and strongly agree), with less than 20% unsure and a small remainder disagreeing. Although 26% indicated their confidence in the debates as a fair way of being assessed, up to 32% of surveyed students were undecided, and the remainder disapproved. Amongst the reasons noted for disapproval was the idea of sharing the marks in a context where some students contributed a fair amount of effort compared to their classmates. Most surveyed students found the debates quite beneficial for the reasons already identified by the lecturer. Fifty-six per cent (strongly agree and agree) reported feeling less isolated in remote learning because of it. Although 70% (strongly agree and agree) of the respondents still preferred individual history assignments as opposed to group work, some 42% (strongly agree and agree) enjoyed it, with about 31% undecided, possibly as this was their first time contributing to debates in relatively large groups and as a form of assessment.

In answering the narrative part ofthe survey, most students approved of group work. But some did cite their displeasure with other students who were either rude or uncooperative. There was, as mentioned, certainly a need to inculcate a sense of etiquette, which in itself is a critical skill to impart within the context of debating and beyond. Others complained about having to do more work than others and felt that some students got more marks than their work. But even these challenges were crucial life lessons about working with peers and in groups. Some people will always get credit for others' work. However, despite these limitations, most students felt that group work was instrumental in bridging the digital divide, allowing them to familiarise the names of other students in the thread, work together with others and collectively make a case for whatever side of the historical debate they were part of. Some students could engage with their peers and at least, for that time, be part of a history class.

Group work: Third year

In the third-year group of 77 students, a flexible approach to group work was adopted. While they were encouraged to participate in groups, a few students were allowed to work individually if they could not get in touch with peers or preferred to work alone. In general, they found group work exciting, and the feedback was positive, except in a few cases where some reported that their group members did not participate or contribute adequately.

Peer learning was the primary motivation, but the lecturer modelled the group assignments to assess students individually. The lecturer regarded group work as a helpful tool but indicated that it could be a source of frustration for some students, so they opted for a combination of group and individual work. This lecturer achieved several objectives from this approach and invited students to collaborate, share readings and thoughts, and work together to make their case on a particular historical issue. But the lecturer also avoided giving collective marks, as students were invited to produce individual papers. The two-part group assessment invited students to work together to produce a proposal on a historiographical topic to examine and, secondly, a full paper developed from that proposal. But several historiographical themes were proposed, and each student chose the one they were most interested in. After utilising readings provided online and those they researched, they were allowed to discuss these before producing individual final assignments.

In this third-year module, 31 out of 77 (40%) students took part in this survey. However, this particular module is unique because it has far fewer students than the first and second-year courses, many of whom are in their final year before graduation. They had a year and a few months of on-site university experience and therefore knew each other relatively well.

They had also met and interacted regularly with most history teaching staff, only having been forced to go online because of the pandemic in the first months of their second year. Their experiences with group work, and their responses towards it, would unsurprisingly be informed by more experience.

Over 80% of participants approved (strongly agree and agree) of how the group work was organised. However, although perceived as well organised, about 45% were unsure whether or not group work was a fair way of being assessed. More than 75% of students (strongly agree and agree) indicated that group work left them feeling less isolated in the context of online learning. However, like the first and second-year students, most students, almost 75% (strongly agree and agree), preferred to do individual history assignments. Yet 65% of the students enjoyed (strongly agree and agree) the group work experience. This was consistent with group work's role in the other history modules of different levels.

In the case of the third-year students, they took advantage of pre-established networks and friendships. They also had more university experience and fully knew how a university education works. As a result, they could easily work together even as they submitted individual history assignments on which they were assessed. Complaints of non-participation were much less of an issue, especially as the groups were much smaller, sometimes consisting of no more than three or four students each, and they were individually assessed. But like the first- and second-year modules, despite them knowing and having met and worked with each other, they still felt that group work took away the feeling of isolation. Some felt relieved to be working with others. Although some indicated that online group work could never replace in-person engagements, they still felt that this helped them interact with others and engage the issues more closely during this crisis.

Conclusion: Grouping or groping

The outbreak of Covid-19 resulted in a shift to the pandemic classroom that demanded adjusting teaching approaches and developing imaginative pedagogical approaches. Among these included the group work approach as one of the toolkits of teaching and assessment practices. Several scholars took remote working, teaching and learning as the "new normal", claiming that online education had heralded a new and better virtual university of the future. But, to be clear, whatever approaches the history lecturers used in this study were designed to make the most of a crisis. The target for most university administrations was to save the academic year, but some mistook that as a testament to a successful transition to new and better online education. This resulted in well over 300 university academics (teaching staff) pushing back by signing a petition claiming that the 2020 academic year had not been as successful as university administrations claimed. They cited the loss of student and lecturer interactions, a reliance on unreliable platforms such as Whatsapp, voice notes and inadequate gadgets to allow all students access. They were especially concerned about the cost-saving objectives of the universities, which may have wanted to shift towards permanent online learning.41 The pandemic proved to be not just a health one but also affected various aspects of university education. In this context, this article considers group work in the discipline of history. It shows that in the context of the pandemic, the pandemic classroom can adopt and adapt group work, not as the only teaching and assessment tool but as an important aspect of other approaches. As shown by the survey among history students and lecturers above, we look at group work as a way of bridging the digital divide and allowing students to have some form of interaction, reduce their isolation and encourage commitment and participation in the learning process.

The methodology used was designed to test the efficacy of group work as a method of assessment for the discipline of history under remote-learning crisis conditions. It is not necessarily a testament to how good group work is, but as the questions and responses by students and staff reveal, a way of temporarily overcoming the digital divide or remote disconnect. In that sense, online learning allowed lecturers to group the divide in various inventive ways, such as providing platforms for debate, such as in the second year where students could, in their various groups, collaborate and then produce a combined history task or assignment. In the case of third-year students, even if they were assessed individually, group work created a platform for discussion amongst peers to share thoughts, arguments and ideas-skills so integral to studying history. At least in working together on a group assignment, first-year students had some sense of belonging to this new and often unknown entity, the university-and history class. Generally, group work allows, under strenuous conditions, students an opportunity to work with other students, making them feel less isolated and part of a university institution. Yet, according to the majority of history students surveyed, although they appreciated the benefits of group work, they still insisted that they would rather write individual history assignments and experience in-person history lectures where discussion and debate can be prompted, led and monitored. In this case, compared with in-person interactions, online group work's limitations and challenges were akin to groping the divide. Even if group work incorporated students who, in most cases, have never met each other, as in the case of first-year students, and involved them in some form of an inclusive learning experience, this is still insufficient. The answers provided by the history lecturers and the history students' responses also reveal how in-person learning and individual work remain the most effective way of teaching-even though group work helped reduce the effects of the pandemic classroom.

1 M Hubbs, "Remote learning in the pandemic: lessons learned", Campus Technology, 16 December 2020, (available at https://campustechnology.com/articles/2020/12/16/remote-learning-in-the-pandemic-lessons-learned.aspx, as accessed on July 2021),

2 R Danisch, "The problem with online learning? It doesn't teach people to think", The Conversation, 13 June 2021, (available at https://theconversation.com/the-problem-with-online-leaming-it-doesnt-teach-people-to-think-161795, as accessed on July 2021)

3 See for example, S Akoojee and M Nkomo, "Access and quality in South African higher education: the twin challenges oftransformation", South African Journal of Higher Education, 21(3), 2008, pp. 385-399; P Mukwambo, "Policy and practice disjunctures: quality teaching and learning in Zimbabwean higher education", Studies in Higher Education, 45(6), 2020, pp. 1249-1260.

4 Parliamentary Monitoring Group, "Saving the 2020 academic year: DHET, USAf and SAUS briefings; with Minister", 23 October 2020, (available at https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/31288/, as accessed on 10 December 2021).

5 N Duncan, "How to bolster hybrid teaching and learning competencies", University World News, Africa Edition, 20 January 2022, (available at https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20220116195416213, as accessed on 30 January 2022).

6 G Marinoni, H van't Land and T Jensen, "The impact of Covid-19 on higher education around the world", International Association ofUniversities,(available at https://www.iau-aiu.net/IMG/pdf/iau_covid19_and_he_survey_report_final_may_2020.pdf).

7 N Duncan, "Online learning must remain a key component of teaching systems", Mail & Guardian, 22 July 2020; Z. Pikoli, "Academics reject claims that 2020 has been a success for universities", Maverick Citizen, 14 December 2020.

8 D Burns, N Dagnall & M Holt, "Assessing the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on student wellbeing at universities in the United Kingdom: a conceptual analysis", Frontiers in Education, 14 October 2020, (available at https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2020.582882); A Okada & K Sheey, "Factors and recommendations to support students' enjoyment of online learning with fun: a mixed method study during Covid-19", Frontiers in Education, 11 December 2020 (available at https://doi.org/10.3389/fed-uc.2020.584351 as accessed in July 2021).

9 D Burns, N Dagnall & M Holt, "Assessing the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on student wellbeing at universities in the United Kingdom: a conceptual analysis", Frontiers in Education, 14 October 2020, (available at https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2020.582882 as accessed in August 2021).

10 Y Zhai & X Du, "Addressing collegiate mental health amid Covid-19 pandemic", Psychiatry Research, vol. 288, June 2020, (available at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165178120308398?casa_token=ViATu-dFtmEAAAAA:SThuol0WUqY0aFshFG8ylrUYEUf-39MzAyoJH9KAF9wX7wWonwB26DdrR8HLy41lJP84zUec1OQ).

11 Y Zhai & X Du, "Addressing Collegiate Mental Health amid Covid-19 pandemic", Psychiatry Research, vol. 288, June 2020, (available at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165178120308398?casa_token=ViATu-dFtmEAAAAA:SThuol0WUqY0aFshFG8ylrUYEUf-39MzAyoJH9KAF9wX7wWonwB26DdrR8HLy41lJP84zUec1OQ).

12 D Burns, N Dagnall & M Holt, "Assessing the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on student wellbeing at universities in the United Kingdom: a conceptual analysis", Frontiers in Education, 14 October 2020, (available at https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2020.582882 as accessed in August 2021).

13 D Burns, N Dagnall & M Holt, "Assessing the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on student wellbeing at universities in the United Kingdom: a conceptual analysis", Frontiers in Education, 14 October 2020, (available at https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2020.582882, as accessed in August 2021).

14 R Danisch, "The problem with online learning? It doesn't teach people to think", (available at https://theconversation.com/the-problem-with-online-learning-it-doesnt-teach-people-to-think-161795, 13 June 2021, as accessed in August 2021).

15 M Dooris, "The 'health promoting university' as a framework for promoting positive mental well-being: a discourse on theory and practice", International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 1, p. 34.

16 D Burns, N Dagnall & M Holt, "Assessing the impact of the Covid-19 andemic on student wellbeing at universities in the United Kingdom: a conceptual analysis", Frontiers in Education, 14 October 2020, (available at https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2020.582882, as accessed in August 2021).

17 G Krull & D de Klerk, "Online teaching and learning: towards a realistic view ofthe future", (available at https://www.wits.ac.za/covid19/covid19-news/latest/online-teaching-and-leaming-towards-a-realistic-view-of-the-future.html, as accessed on 11 December 2021).

18 G Krull & D de Klerk, "Online teaching and learning: towards a realistic view ofthe future", (available at https://www.wits.ac.za/covid19/covid19-news/latest/online-teaching-and-learning-towards-a-realistic-view-of-the-future.html, as accessed on 11 December 2021).

19 G Marinoni, H van't Land & T Jensen, "The impact of Covid-19 on higher education around the world", International Association of Universities, (available at https://www.iau-aiu.net/IMG/pdf/iau_covid19_andhe_survey_report_fina_may_2020.pdf).

20 G Marinoni, H van't Land & T Jensen, "The impact of Covid-19 on higher education around the world", International Association of Universities, (available at https://www.iau-aiu.net/IMG/pdf/iau_covid19_andhe_survey_report_fina_may_2020.pdf).

21 R Danisch, "The problem with online learning? It doesn't teach people to think", (available at https://theconversation.com/the-problem-with-online-learning-it-doesnt-teach-people-to-think-161795, 13 June 2021, as accessed in August 2021).

22 DW Johnson & RT Johnson, "An educational psychology success story: social interdependence theory and cooperative learning, Educational Researcher, 38(5), 2009, pp. 365-379. (available at http://edr.sage-pub.com/cgi/content/abstract/38/5/365).

23 Encylopedia Britannica, Athens (available at https://www.britannica.com/topic/education/Athens, as accessed on 30 January 2022).

24 T Falola & T Fleming, "African civilisations: from the precolonial to the modern day", in World Civilisations and History of Human Development, 1, pp.123-140, (available at https://pdf4pro.com/view/african-civilizations-from-the-pre-colonial-to-the-modern-day-53bf66.html).

25 MK Smith, "The early development of group work", The Encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education, 2004, (available at https://infed.org/mobi/the-early-development-of-group-work/, as accessed in July 2021).

26 D Burns, N Dagnall & M Holt, "Assessing the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on student wellbeing at universities in the United Kingdom: a conceptual analysis", Frontiers in Education, 14 October 2020, (available at https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2020.582882 as accessed in August 2021).

27 E Brown, "6 advantages of collaborative learning", 2007. ezTalks. (available at https://www.eztalks.com/online-education/advantages-of-collaborative-learning.html).

28 M Lotriet M Pienaar, " Cooperative and collaborative learning", Online resource. University of Pretoria. (Unpublished), 2020. (available at https://eduvation.up.ac.za/cooperative-collaborative-learning/index.htm, as accessed on 30 January 2022).

29 "Higher education looking into controversial reports on UNISA", 19 October 2021, (available at https://www.careersportal.co.za/news/higher-education-looking-into-controversial-reports-on-unisa, as accessed on 15 November 2021).

30 JW Johnson & RT Johnson, "New developments in social interdependence theory", Genetic Social and General Psychology monographs, 131(4), November 2005, p. 137.

31 J. Johnson & RT Johnson, "New developments in social interdependence theory", Genetic Social and General Psychology monographs, 131(4), November 2005, pp. 306-307.

32 ME Pritchard & GS Wilson, "Using emotional and social factors to predict student success", Journal of College Student Development, 44(1), January/ February 2003, p. 19.

33 D Burns, N Dagnall & M Holt, "Assessing the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on student wellbeing at universities in the United Kingdom: a conceptual analysis", Frontiers in Education, 14 October 2020, (available at https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2020.582882 as accessed in August 2021).

34 S Handel, "Positive peer pressure", (available at https//www.theemotionmachine.com/positive-peer-pressure/, as accessed on 29 December 2021); See also P. Baruah, B.B. Boruah, "Positive peer pressure and behavioral support", Indian Journal of Positive Psychology, 7(2), 2016, pp. 241-243.

35 M Seligman, Flourish: a visionary new understanding of happiness and wellbeing, Washington, DCPsycNet, 2011.

36 A Klawitter, "Five challenges students face with online learning in 2022", 2 March 2022 (available at https://meratas.com/blog/5-challenges-students-iace-with-remote-learning/ as accessed on 20 November 2021).

37 T Nguyen et al., "Insights into students' experiences and perceptions of remote learning methods: from the Covid-19 pandemic to best practice for the future, Frontiers in Education: Educational Psychology, 9 April 2021. (available at https://ww.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2021.647986/full, as accessed on 20 November 2021).

38 T Nguyen (et al), "Insights into Students' Experiences and Perceptions of remote learning methods: From the Covid-19 pandemic to best practice for the future, Frontiers in Education: Educational Psychology, 9 April 2021. (available at https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2021.647986/full as accessed on 20 November 2021).

39 K Brzezicki, "Talking about history: group work in the classroom-practice and implications", Teaching History, 64, 1991, pp. 12-16.

40 A Prud'homme-Genereux, "21 ways to structure an online discussion, part three", Faculty Focus (2021), (available at https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/online-education/online-student-engagement/21-ways-to-structure-an-online-discussion-part-three/ as accessed on 29 December 2021).

41 Z Zukiswa, "Academics reject claims that 2020 has been a success for universities", Maverick Citizen, 14 December 2020, (available at https://cornerstone.ac.za/academics-reject-claims-that-2020-has-been-a-success-for-universities/, as accessed on 2/01/2021).