Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Yesterday and Today

On-line version ISSN 2309-9003

Print version ISSN 2223-0386

Y&T n.27 Vanderbijlpark 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2223-0386/2022/n27a5

ARTICLES

History Education during COVID-19: Reflections from Makerere University, Uganda

Dorothy Kyagaba Sebbowa

Makerere University Kampala, Uganda dksebbowa@gmail.com; 0000-0002-5705-3029

ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 pandemic forced most governments in Africa to temporarily close educational institutions in attempt to reduce the spread of the pandemic. In Uganda particularly, Higher Education Institutions, Universities and schools adopted the online and blended approaches to afford continuity of learning during the lockdown. This article provides a reflection of the opportunities, challenges and lessons learnt in teaching and learning of history during the COVID-19 pandemic. Qualitative data was obtained from a narrative inquiry of the researcher's own teaching experience and interviews with pre-service history teachers from Makerere University. Findings indicated that, while online and blended approaches facilitate history education through Makerere University e-Learning (MUELE) Learning Management System, WhatsApp exchanges, Zoom, emails, mobile phone text messaging and print media; there were persistent challenges such as limited Information Communication Technology (ICT) tools, digital illiteracy, digital divide, increased workloads as well as social-emotional stress and distractions at home. The article concludes with a key lesson for Teacher Education programmes to shift the way they train pre-service history teachers to embrace online learning with access to offline, downloadable, print learning materials to facilitate blended learning approaches. This is relevant in preparation of different generations of teachers to integrate blended pedagogy in History Education in response to the new normal caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: History Education; COVID-19; Pre-service history teacher; online learning; Makerere University.

Introduction

The outbreak of the COVID-19 and the subsequent lockdown of educational institutions affected educators, teachers and learners worldwide, with over 209 million learners in Africa physically out of school (UNESCO, 2020). In Uganda for example, more than 73,000 learning institutions closed where 15 million learners and 54,800 teachers could not engage in physical pedagogical conversations (Kabugo, 2020). One of the reasons for total lockdown of institutions of learning was to enforce social distancing as Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for mitigating the spread of COVID-19. However, Mahaye (2020) reported that, schools losing long periods of learning due to the disease outbreak could result in a disruption of the curriculum and could cause learners to be demotivated to learn, even when the disease outbreak ends. Consequently, in an attempt to ensure continuity of learning during the COVID-19 lockdown, the Ministry of Education and Sports (MoES) in Uganda issued guidelines for provisions of sustained learning on the 20th of March, 2020 (MoES, 2020).

Following the provisions for sustained learning, primary and secondary schools engaged with print, self-study materials, audio, visual learning materials and transmissions through radios and televisions to facilitate the delivery of lessons during the COVID-19 era. While, at higher institutions of learning, universities were instructed to embrace the eLearning approach to save the academic year (New Vision, 2020). This, therefore, implied a transition from the traditional face-to-face teaching methods to technology-based learning mediated by Learning Management Systems (LMS), emails, Zoom, WhatsApp, Skype, Google classroom and mobile phone text messaging as online pedagogical interventions in the new normal. The abrupt shift in university pedagogy ushered in a COVID-19 pandemic shock as almost all universities in Uganda where ill prepared for unconventional approaches with related financial implications (Nawangwe, Muwagga, Buyinza & Masagazi, 2021). Therefore, university pedagogies during the pandemic proved costly as they involved embracing synchronous based learning for teachers and students to interact with each other in real-time (Atmojo & Nugroho, 2020). While, for asynchronous based learning, online pedagogical interactions happened at different times and in different contexts.

The study emerges from the History Education Unit, School of Education (SOE), Makerere University where the researcher is a teacher educator and facilitator of the history methods (history education) courses offered at undergraduate and postgraduate levels. In this research, the terms learners and students are synonymously used to mean pre-service history teachers. This article aims to reflect on the teaching and learning of history during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, the article provides a snapshot of the potentials and challenges encountered during the teaching and learning of history in this time. Consequently, lessons learnt are documented which might inform decisions and strategies for enhancing History Education in the new normal.

Consequently, the reflection questions were as follows: What are the potentials of teaching and learning history using the blended/online approaches during the COVID-19 pandemic? What are the challenges of teaching and learning history using the blended/ online approaches during the COVID-19 pandemic? What are the lessons learnt from teaching and learning history using the blended/online approaches during the COVID-19 pandemic?

The proceeding section highlights a literature review on teaching and learning processes during COVID-19, drawing examples from the global, African and Ugandan History Education pedagogical landscape.

Literature review

Research conducted on intra-period, digital pedagogy responses to COVID-19 across 20 developed and developing countries revealed that, higher education providers have been diverse, from having no response through to social isolation strategies on campus and redrafting of the curriculum to fully online offerings (Crawford, Butler-Henderson, Rudolph, Malkawi, Glowatz, Burton, & Lam, 2020). Thus, Crawford et al. (2020) recommended that the higher education sector unite to postulate a future where students receive support digitally, without compromising academic quality and standards of the curriculum. Consistently, a study conducted by Allen, Rowan and Singh (2020) on teaching and teacher education in the time of COVID-19 indicated that teachers and teacher educators' move to online modes of delivery in order to keep students engaged in learning has significantly intensified their workloads and presents a considerable hardship for adoption to the new normal. Accordingly, Atmojo and Nugroho (2020) investigated how EFL (English as a Foreign Language) teachers carry out online EFL learning and its challenges. Their findings revealed that teachers must have sufficient knowledge and skills to teach online since it requires more time than face-to-face teaching. To this end, Pokhrel and Chhetri (2021) recommend that, education systems across the world invest in the professional development of teachers' ICT skills and effective pedagogy in the new normal. Moreover, Czerniewicz (2020) suggests the need for planning and engagement with simple technologies that work for specific contexts since technologies are never neutral.

Tumwesige (2020) studied the systematic opportunities and challenges of diffusing e-learning in the context of Uganda. Tumwesige reports that, the difficulty of accessing learning technologies and the level of digital literacy skills between privileged and the deprived groups continue to widen the education and digital gap in Uganda. A study on how COVID-19 response measures in Uganda have affected the lives of adolescent young people was conducted in May-June 2020 (Parkes, Datzberger, Howell, Kasidi, Kiwanuka, Knight, Nagawa, Naker & Devries, 2020). The findings revealed that, most young people had no or limited access to the resources needed to engage with these materials and support. The research seemingly suggests a need for government and parental intervention to support pedagogical processes. While Sali (2020) studied the effects of Uganda government's COVID-19 response from a gender perspective, Nabukeera (2020), on the other hand, probed the instructional strategies in Higher Education in Uganda following a case of Islamic University Female Campus. Kabugo (2020) proposed a model for using Open Educational Resources to enhance Students' Learning Outcomes during the COVID-19 schools lockdown. Olum, Atulinda, Kigozi, Nassozi, Mulekwa, Bongomin and Kiguli (2020) assessed the awareness, attitudes, preferences, and challenges to e-learning among undergraduate medicine and nursing students at Makerere University in Uganda and observed that, internet costs, fluctuations, lack of digital skills among students and staff impede e-learning. Bongomin, Olum, Nakiyinyi, Lalitha, Ssinabulya, Sekagga, Wiltshire and Byakika-Kibwika (2021) found that, the COVID-19 pandemic had a significantly negative efect on the clinical learning experience of undergraduate medical students and recommended a review of the current teaching and learning methods to ensure safe and effective learning experiences. Ssenkusu, Ssempala and Mitana, (2021) expounded on how the COVID-19 pandemic has widened opportunities for creativity, innovation and intelligence within education through introducing pandemic pedagogies which are student centred, community and local resource focused.

Bunt (2021) investigated the planning and implementation of an online teaching programme within the History Education subject group at North-West University in South Africa. The study concluded with key recommendations that, teachers and educators empathise with students' learning spaces; make short audio and video recordings accessible on the Learning Management Systems: effect continuous engagement, communication and contact as critical features for successful online learning environments. Consistently, Dlamini (2020) reflected on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on History Education in Higher Education in Eswatini. According to Dlamini, the sudden adoption of remote learning by teacher trainees at the college within a short space of time, had severe constraints such as limited access to internet that compromised the quality of education. Dlamini concluded the study with recommendations such as: 1) The need to adopt continuous professional development and training of staff that will keep History Educators abreast with technology and innovation. 2) The need to invest in appropriate resources such as new technologies, data bundles to improve the quality of online education. 3) The need to transform the education system through the adoption of creative strategies that would enable trainees to learn remotely. Although the results of the research conducted inform the pedagogical terrain in Higher Education, Teacher Education and history education in Africa during the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a paucity of research and gaps on teaching and learning of history in Uganda during the pandemic.

This article provides a reflection of the potentials, challenges encountered, and lessons learnt during the teaching and learning of history in the COVID-19 pandemic. Pre-service history teachers are trained to facilitate content knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge for their future learners in secondary (primary) schools in Uganda and beyond. The proceeding sections describe the teaching and learning history (social studies) in primary and secondary schools during COVID-19 pandemic that greatly inluences and feeds into teacher education (Allen, Rowan & Singh, 2020).

History Education (Social Studies) in primary and secondary schools during COVID-19

That said, social studies and history are the subject disciplines offered to students at primary and secondary school levels in Uganda. For example, social studies are offered at upper primary level (primary four to primary seven) while; history is offered at the Ordinary and Advanced secondary school levels (senior one to senior six). For the case of social studies at upper primary level, the content knowledge covered during COVID-19 included: locations of the districts in Uganda for primary four; location of Uganda on the map of East Africa for primary five; East African Community for primary six and location ofAfrica on maps of the world for primary seven (MoES, 2020). Correspondingly, the history content taught at the secondary school level, during the COVID-19 pandemic, amongst others, included the following. Senior one: inding out about the past, external contacts and pressures in East Africa between 1800 and 1880. Senior two: First World War rise of nationalism in Uganda, Devonshire white paper. Senior three: Islamic movements of the 19th century Christian missionary activities in West Africa. Senior four: African Nationalism. Senior five: French Revolution of 1789. Senior six: Colonial administration (MoES, 2020). Social studies and history content was accessible to learners through teaching and learning mediums such as television, radio print media, downloadable curricular and newspaper papers.

Although teaching and learning of History Education (Social Studies) was somewhat successful during the COVID-19 pandemic, there were persistent challenges that affected the pedagogical process among home learners. For example, radios and televisions were teacher-centred with limited or no interaction between teachers and home learners. This was exacerbated with a lack of guiding questions and engaging activities to facilitate deeper learning and historical thinking among learners. Consequently, home learners never got the chance to ask questions or comment about the print materials and the online lessons delivered on radio and televisions. Moreover, the feedback or comments given to teachers or head teachers through sending SMS, WhatsApp, emails or writing reports, took time and was not instantly received. Thus, continuation of learning history from home meant that many parents, who previously relied on teachers for their children's education, had to guide and support their children's learning (Ezati, Sikoyo & Baguma, 2020). This implied that efective home learning about the past was dependent on parental support, which became increasingly difficult since most parents are illiterate and were busy looking for income and food to support their families.

Similarly, learning from home faced disruptions such as house chores; learners from rural areas were always in gardens while teaching was taking place (Senkusu et al., 2021). Home learning materials distributed through newspapers, televisions, radios seemed expensive for most learners from disadvantaged backgrounds and rural communities with a lack of electricity and short time span solar power sources (Nawangwe et al., 2021).

There is a need to change the terrain of teaching and learning history in the new normal. The rationale for this pedagogical change is to enhance deeper and meaningful learning achieved through active participation in interpreting the past, collaborative questioning and dialogic conversations between teacher- learner and learner-learner during and post COVID-19. Efective historical learning involves helping young people make sense of the past through engaging with pedagogical practices that evoke meaningful reflection, interpretation and historical inquiry (Bentrovato & Wassermann, 2021).

Additionally, Open Educational Resources and open-source educational tools such as blogs and wikis have been recommended during the pandemic period as user-friendly support tools that enhance collaborative learning and historical knowledge construction (Huang, Liu, Tlili, Yang, Wang, 2020; Bunt, 2021). Thus, cost free educational technologies enhance flexibility in learning while simultaneously addressing the challenges that students cannot go to campus to study in a regular way during the COVID-19 period.

Having said that, the proceeding section focuses on eLearning in History Education at Makerere University during COVID-19.

Embracing eLearning in History Education at Makerere University during the COVID-19 pandemic

The Minister of Education and Sports, Mrs. Kataha Janet Museveni, instructed all universities to embrace the e-learning approach as an intervention to COVID-19 (New Vision, 2020). Thus, guidelines to enhance online learning were set up by the National Council of Higher Education (NCHE) in Uganda. The NCHE guidelines highlighted the requirement to carry out a needs assessment survey to establish the universities readiness to undertake online learning (New Vision, 2020). Firstly, universities were to ensure financial capacity and adequate human resources to run the online programmes. Secondly, take online infrastructure, facilities and appropriate course design into consideration as well as a good monitoring and evaluation system. The survey revealed that, Makerere University was ready to embrace eLearning given that academic staf were undergoing training in developing online courses as well as existing ICT infrastructure.

At Makerere University, an established Open, Distance and eLearning (ODEL) policy that supports and directs online learning has been in place since 2015. The university organised with telecommunication companies to have all the university portals accessed by the students at zero charges during the COVID-19 lockdown. Furthermore, to promote eLearning during the lockdown and beyond, Makerere University started engaging computer manufacturers on the possibility of obtaining affordable yet good quality laptops for students that could be paid off on a hire purchase basis over an agreed period (New Vision, 2020). However, while staff in the History Education Unit had personal laptops, most students, particularly pre-service history teachers, did not have the required funds to purchase the laptops, and this curtailed the eLearning plans and processes.

Consequently, Makerere University's ODEL academic staf, embarked on conducting capacity building training sessions on Zoom for all academic staff (history educators included) in the use of digital technologies and alternative assessment modalities. The continuous training sections were relevant in ensuring continuity of history teaching, learning and examinations to complete the semester and academic year. Thus, the training sessions focused on the assessment modalities and use of online materials to develop history teaching and learning content and activities uploaded on the LMS called Makerere University e-Learning (MUELE) platform. Alternative assessment modalities for undergraduate and postgraduate programmes in the History Education Unit. These included: traditional assessment submitted online: essays, case studies, papers reviews and report writing. Online interactions: contributions to forums, chats, blogs, wikis, reading summaries, collaborative learning, critical reviews, online presentations, online debates and electronic portfolios. For the case of summative exams, take home papers and open books exams, relective journals, History Educators were required to atach a rubric for each of the examination papers.

Although a number of challenges constrained the execution of the online assessment modalities such as: system overload and break down due to too many student users, power outages, delay in uploading examinations on MUELE, internet fluctuations, lack of internet bundles to keep home students online and late submissions of take-home examinations; eLearning, coupled with multiple assessment modalities, was successful and ensured the continuity of History Education during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In this article, relections on the potentials, challenges and lessons learnt from History Education during COVID-19 comprised a narrative inquiry (Clandinin, 2006) of my teaching experience presented in the research methodology section.

Research methodology

The study adopted a narrative inquiry as a methodology to afford sharing of lived teaching experience (personal) and case study pre-service history teachers' experiences (social) on History Education during COVID-19 in the School of Education, Makerere University context. Narrative inquiry methodology processes present ways of inquiring into personal experiences, participants' experiences, as well as the co-constructed experiences developed through the relational inquiry process (Clandinin, 2006). Therefore, narrative inquiry enabled relections and ways of thinking about the lived teaching experience from personal (own reflections), social interactions (case study participants) dimensions with openness to multiple voices aligning to the past, present and future (Clandinin, 2006).

Data collection methods included; narrative inquiry into my lived teaching experience as a history teacher educator, telephonic interviews from four pre-service history teachers in their second year of study and face-to-face interviews from four pre-service history teachers in third year (finalists) who had returned to complete the semester. Therefore, eight case study participants were purposively selected to take part in the study (Yin, 2009). The rationale for selection sampled case study participants was for two reasons:

firstly, they were those who actively participated in debates on various history concepts and pedagogical issues on the history methods course WhatsApp groups. Secondly, participants who owned mobile phones, confirmed availability and willingness to take part in the study. Moser and Korstjens (2018) assert that key informants should be selected based on their special knowledge, ability to gain access to participants within the group studied and their willingness to share information and insights with the researcher. For ethical considerations, the eight (8) case study participants were assigned numbers for easy identification depending on their years of study. These included participants 2.1, participant 2.2, participant 2.3, participant 2.4, participant 3.1, participant 3.2, participant 3.3 and participant 3.4.

Case study participants were required to share their experiences and narratives on History Education during the COVID-19 pandemic, with a reflection of the potentials, challenges and lessons learnt. Thematic analysis informed the data analysis process as themes were derived from the number of repeated times a particular idea/ item in response to the reflection question appeared in the data set (Bryman, 2012; Miles, Huberman & Saldana, 2014). Therefore, dominant words, phrases and significant codes reflecting on the potentials, challenges and lessons learnt from the teaching and learning of history during the pandemic where identiied.

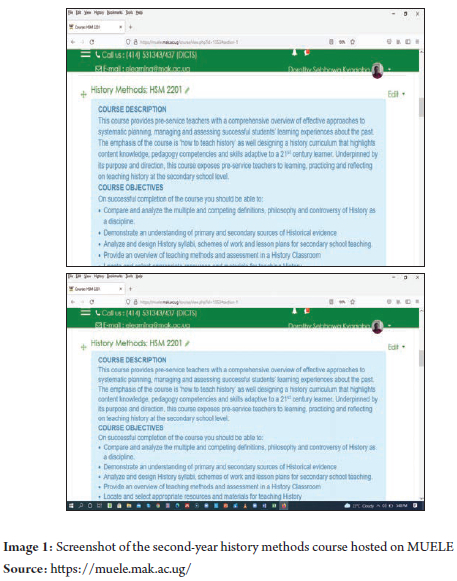

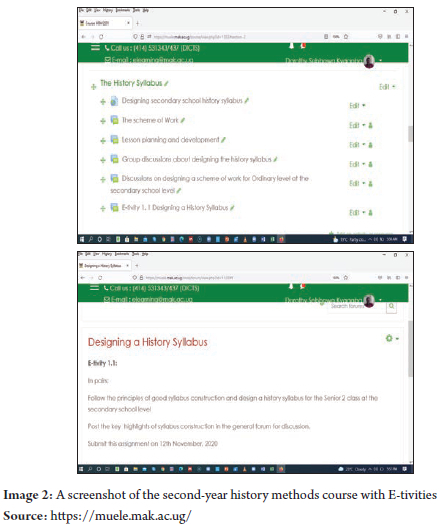

Narrative inquiry of my experiences on teaching and learning of history during COVID-19

As a teacher educator at the university, I tutor the history methods (history education) course that initiates pre-service teachers to embrace multiple pedagogical approaches in history classrooms to cater for the diverse learning styles of their future students. History methods is a course taught to pre-service teachers in their second and third years of study. The History Education Unit embraced online and blended approaches to sustain learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, the blended learning approach involved a technology-based teaching system using MUELE, emails, Zoom sessions and WhatsApp discussions integrated with the face-to-face teaching approaches. In this paper, blended learning is deined as the integration of the conventional face-to-face learning methods with online and eLearning methods (Mahaye, 2020). Online and eLearning learning approaches on the other hand involve teaching and learning done in synchronous and asynchronous based modes of learning. Synchronous based learning is useful to create contexts and facilities with educators and pre-service teachers interacting with each other in real-time (Atmojo & Nugroho, 2020). While asynchronous based learning can be used for low technology use through discussions and written responses undertaken at different times (Atmojo & Nugroho, 2020). Consequently, history methods online learning involved asynchronous based learning where pre-service history teachers could engage with course activities and assignments at their homes in different times. To this end, I developed online history content coupled with activities hosted on the MUELE platform. (See for example images 1 and 2).

Following images 1 and 2 above, pre-service history teachers in their second year of study were required to enrol for the history methods course and engage with the teaching, learning content and online activities (E-tivities) on MUELE during the COVID-19 lockdown. The MUELE interface integrates various tools such as chat rooms, discussion forums, assignments and online quizzes, to make online teaching more efficient. The history methods course page was developed and maintained with course announcements, course description, course objectives, content outline, assignments, activities and a reading list.

Although I developed an online history methods course on MUELE, it was hard to ensure meaningful, in-depth learning with no practical illustrations of certain topics such as designing a scheme of work and lesson plan. As such, very few pre-service history teachers posted questions in the chat, or engaged with online activities and guiding questions posted in the discussion forums.

As a teacher educator, I was concerned and asked students why they were not actively engaging with the history methods course and activities shared on the MUELE Platform. Many of them cited online constraints such as loss of or forgotten passwords for access, technical challenges, internet connectivity fluctuations, too many online assignments given at the same time. Worse still, some pre-service history teachers had not undertaken capacity-building trainings in the ODEL approach and others had a negative attitude towards online learning. As an educator, I suggest direction and provision of online space on MUELE to enable students to easily play with the user interface and acclimatise themselves with the online environment. Correspondingly, Mokoena (2013) argues that an educator must be sure to provide students with directions for online discussions that are simple, to the point that they are guided on what activity follows the other as well as appropriate technical support (user guides) for successful online learning.

Following the challenges with MUELE, presented in the preceding section, I embarked on alternative online teaching and learning platforms such as: Zoom, emails and WhatsApp. I requested the course coordinators/leaders to create WhatsApp groups and obtain emails from the respective pre-service history teachers. Thus, the WhatsApp group was formed and introductory messages and strict rules regarding the information were shared. Consequently, pre-service history teachers unanimously agreed that the history course notes and activities shared on Zoom, emails and WhatsApp groups afforded them easy access. Therefore, to facilitate a deeper understanding of the content taught on Zoom, I encouraged question and answer sessions afforded by chat, audios and breakaway sessions to facilitate group discussions of the topic under study. The Zoom sessions were collaborated with discussion groups on WhatsApp to elucidate the content knowledge and answer students' questions. Accordingly, (Guyver, 2013) argues that attaching relevance to history education requires teachers to transform historical content into lesson sessions and materials that identify and atend to students' learning styles and ideas.

However, I observed that, only 50 to 100 students, at most, out of over 250 attended the Zoom lecture sessions with others losing connectivity dropping off. The reasons for the low attendance might have been that some pre-service history teachers especially those from rural areas and disadvantaged backgrounds could not aford internet bundles, lacked laptops, smart phones, and computers while others engaged in agricultural activities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, some pre-service history teachers might have faced a challenge of engaging with Zoom, as they had not been previously taught/oriented in the online learning mode. This is in conformity with Dlamini (2020) who observed that history trainees from the rural areas suffered the most, as they could not access the online lessons due to financial constraints, poor network coverage and negative attitudes towards ICTs. The remedy for this challenge was to download and print learning materials shared on Zoom to ease access to all the disadvantaged groups of students. Therefore, engagement with offline, downloadable, print learning materials should partially overcome the challenges related to ICT infrastructure and internet connectivity. Accordingly, Pokhrel and Chhetri, (2021) recommends that, in developing countries where the economically backward students are unable to aford online learning devices and data packages, it becomes increasingly relevant for students to engage in oline, print materials, activities and self-exploratory learning.

Given that, the pre-service history teachers had to engage with practicums of school practice and yet all schools where closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic; the School of Education adopted flexible supervision approaches to ensure the smooth running of teaching practice sessions. Pre-service teachers participated in microteaching sessions with a peer-to- peer teaching of a specific history topic/subtopic or concept of their choice under the guidance of the supervisor (teacher educator).

Following the partial lifting of the COVID-19 lockdown, the Ministry of Education and Sports in Uganda, provided guidance on the re-opening of universities for face-to-face teaching in a phased manner. This implied that cohorts of students would attend physical classes while others would stay online in alignment with the blended learning approach.

To supplement the narrative inquiry of my lived experience, I share the participants' indings and discussions in the proceeding sections.

Findings and discussions

The section presents and discusses the qualitative findings drawn from the case study of pre-service history teachers' reflections/narratives on the potentials, challenges and lessons learnt from teaching and learning history during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Potentials of learning history during the COVID-19 pandemic

Three major themes arose out of the data, namely: increase in self-study reading, learning history facilitated by ICT tools and studying remotely at home is a learning space with less distraction from peers.

Increase in self-study reading:

Findings revealed that more self-reading and study of history textbooks, lecturers' notes and newspapers was done to facilitate the learning of history during the COVID-19 pandemic. As relected in the salient qualitative sentiments below:

As students, we have done more reading oftextbooks during this COVID-19 period. Lecturers recommended a number of reading materials that we could access online, home libraries and internet. I have personally done extensive reading of documents and newspapers. A case in point is the course work that was given to us in Political ideas [course]; I completed it with the help of the New Vision Newspaper. (Participant 3.2)

While another pre-service teacher remarked that,

I needed to supplement my understanding of the lecture notes shared on MUELE and emails through doing more reading of history texts. Some concepts were new to me yet I had no one to consult while at home. (Participant 3.4)

The sentiments suggest that pre-service history teachers engaged in extensive reading and obtained content knowledge from history resources to supplement their lecture notes during the COVID-19 pandemic. These qualitative findings provide evidence that the COVID-19 period increased opportunities and unstructured time for individual reading and consultations from multiple sources of historical information in the online space. However, although the indings were representative of a limited number of case study participants, they provided useful insights into and evidence ofincreased self-study reading of history texts with minimal guidance of educators during the time of the pandemic, unlike the normal structured classroom seting.

These findings, however, contrasted with other research; Aguilera (2020) found that reading and concentrating from home during the COVID-19 period was diicult due to distractions from family members, noise and housework. Aguilera postulated that it was very challenging for students to engage in self-study reading since students view home as a relaxation space. Similarly, Tumwesige (2020) found that, 80% of Uganda's youth, including university students, are from economically disadvantaged backgrounds, especially rural areas characterised with a lack of reading resources, and have no access to internet to obtain online reading materials. To this end, Pokhrel and Chhetri (2021) recommend online pedagogies that ensure lexibility with constant guidance and counselling sessions, since most students at home have undergone psychological and emotional distress, which prohibits their engagement in productive reading.

ICT tools facilitated learning history:

Qualitative findings indicated that, pre-service history teachers learnt history through the mediation of technological tools such as Zoom sessions, WhatsApp exchanges, emails and text messages during the pandemic. This is highlighted in the salient comments below:

I have learnt history during this pandemic period in innovative ways such as: participating in Zoom sessions organized by the lecturer; question and answer sessions on our history WhatsApp group, as well as reading lecture notes downloaded and printed out from MUELE. I am now ready to sit for the end of semester exams. I can't wait to sit in the tent in freedom square on graduation day. (Participant 3.1)

While another pre-service history teacher lamented that,

Having waited for a long time I accessed my email from the School of Education Computer lab. I was able to save the lecture notes on flash disk printed them out and I read them while at home. However, I request lecturers to share notes on photocopies to ease and soften our life. Alternatively, students who cannot afford daily data areforwarded text messages so that they can receive communication in as far as the course notes are concerned. (Participant 3.3).

The findings suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic period created opportunities for innovative ways of learning history through, Zoom, WhatsApp, downloading notes from MUELE and accessing emails. This therefore implies that, pre-service history teachers, engaged in extended questioning and answering sessions, group discussion forums, in Zoom breakaway rooms, MUELE and WhatsApp, increased their understanding of the history topics under study. These qualitative findings are in conformity with literature from Ali and Abdalgane (2020) and Bunt (2021) who found that the use of eLearning tools facilitated pedagogies of English literacy at a university in Saudi Arabia and History Education at North-West University in South Africa during the pandemic. Correspondingly, Huang et al. (2020) and Czerniewicz (2020) recommend user-friendly, context and discipline specific ICT tools to enhance collaborative learning and knowledge construction between educators- students and students-students. However, indings indicate that access to ICT tools and data packages were expensive for some pre-service teachers who had to print lecture notes from the School of Education Computer lab. This sentiment echoes my earlier interpretation of engagement with offline, downloadable, print learning materials to address challenges related to ICT infrastructure and internet connectivity.

Studying remotely at home is a learning space with less distraction from peers:

Responses show that, pre-service history teachers studied conveniently at home with limited competition for resources and distraction from their peers. This is reflected in the qualitative sentiment below:

Facilities and resources at home have no competition at all. Moreover, there is no peer influence and distraction from course mates save for the noise coming from children in the neighborhood. (Participant 2.1).

While another pre-service history teacher revealed that,

Studying from home reduces on incurring expenses such as public transport costs from home to campus, no accommodation costs at the hostels and halls of residence. (Participant 2.4).

The findings are indicative of a positive dimension of studying history at home, with less distraction from peers coupled with no accommodation and public transport costs. This is in conformance with Dogar, Shah, Ali and Ijaz (2020) who argued that since the cost of public transport and accommodation constrain most students at universities in developing countries. The strategy of online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic proved a luxury and a great relief to both parents and students who do not have to incur daily public transport costs or accommodation costs in student halls of residences or hostels. On the contrary, Aguilera (2020) and Pokhrel and Chhetri (2021) observed that reading and studying remotely from home during the COVID-19 period proved difficult due to distractions from family members, noise, assisting parents in farm activities such as agriculture, tending to cattle and household chores.

Challenges of learning history during the COVID-19 pandemic

Four major themes emerged from the challenges: ICT constraints, digital illiteracy, limited interactivity, social-emotional stress and financial constraints at home.

ICT constraints:

Findings revealed that, pre-service teachers faced access and log in challenges on the Learning Management System, MUELE. This is highlighted in the sentiments below;

I failed to log in to MUELE after several encounters as the system rejected my password at all times, efforts to reset passwordfailed and I resorted to email. Moreover, I need to load internet data on my mobile phone on a daily basis which is very expensive to sustain as my family is suferingfinancially hardships due to the COVID-19 lockdown. (Participant 2.2)

While another pre-service teacher indicated that,

There is a problem of system overload due to very many users on MUELE. Sometimes I log into MULELE and I lose direction and yet there is limited technical assistance for support and help. (Participant 2.4)

The qualitative sentiments provide evidence of Dlamini's (2020) point that ICT constraints existed in higher education institutions in Sub Saharan Africa for decades, even before the rapid even before the rapid spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. Consistently, ICT related challenges such as lack of ICT tools, access and login constraints, and internet connectivity fluctuations have affected the online learning terrain ushered in by the pandemic. This, therefore, implies that educators and pre-service teachers, as agents of pedagogical change, need to adopt creative pedagogical approaches that can accommodate remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. From my own point of view, the challenge of internet connectivity luctuations might be addressed by downloading history course content during off peak hours, working offline. Additionally, a MUELE user guide (content), short introductory video clips, ICT support desk and an online play space (without strict rules and structures but for trial and errors) should be created on the LMS to address technical challenges as well as facilitate students' acclimatisation with online learning spaces. Correspondingly, Bunt (2021) advises history educators to keep video and audio recordings shorter than those for a traditional class for easy access on the LMS. Bunt postulates that since students learn from home during the COVID-19 pandemic they may not have access to platforms that require large amounts of data.

Digital illiteracy:

In some cases there is limited knowledge of ICT. For example, some students cannot connect to the MUELE application. The findings are indicative of the fact that, pre-service teachers did not have prior experience in learning online.

I did not know how to use MUELE and Zoom. I have a negative attitude towards using ICT tools in the teaching and learning process, they have never adequately trained us to use these tools. We were taught history using chalk and talk. It is always easy for one to teach the way one was taught. Therefore, my attitude has always been low in engaging with ICTs. The role of the teacher should still be vivid even with the existence of ICTs. (Participant 2.3)

While another pre-service teacher said that,

Someone in the café in town helped me to create and email. I have always requested my friends to help me access my email. I do not want to engage with technologies because I have no skills to use computer, besides, they are very expensive to acquire, use and access. (Participant 2.1)

This is in conformity with findings from Tumwesigiye (2020), who noted that the national challenges of poorly developed ICT infrastructure, high bandwidth costs, unreliable supply of electricity, and a general lack of resources to meet a broad spectrum of needs in Uganda, present an impediment to the delivery of content knowledge during the COVID-19 pandemic. Similarly, Dlamini (2020) observed that a lack of digital skills, in- appropriate ICT resources and data bundles among History Educators and teachers constrained the online learning of History Education in Higher Education in Eswatini during the COVID-19 pandemic. This, therefore, suggests a need for continuous capacity building and training of pre-service teachers, in-service teachers and teacher educators on the integrating with ICTs in history education. Professional trainings in integration of ICTs in history education might sharpen digital skills and improve attitudes of both pre-service teachers and history educators.

Limited interactivity:

Findings highlighted a challenge of limited interactivity between pre-service teachers- pre-service teachers, and pre-service teachers- educators during the pandemic. In the case of pre-service teachers in their second year of study, there were limited online interactions.

I have not had any interaction with my lecturer. Sometimes, I ask questions on email and the lecturer takes long to respond. There is no immediate response from the lecturer in case of a burning question yet peers always provide wrong information on the WhatsApp group. Since we access notes from the emails or MUELE and print them out. The discussions on WhatsApp are not sustainable due to lack of data bundles. We just read the course lecture notes; cram the history concepts to pass the end of semester exams. (Participant 2.3)

The sentiments suggest that online learning is constrained by limited interaction between the pre-service teachers and educators. Yet interactions in online learning forums promote deeper, meaningful learning, a sense of community and social connectivity between students and educators. This implies that history educators need to scaffold meaningful student interactions with online history activities that enhance group discussions, question and answer sessions and inquiries mediated by online platforms such as chat rooms, discussion forums, and WhatsApp and Zoom breakaway sessions. This is in accordance with Dlamini (2020) and Bunt (2021) who argue that shared negotiations and collaborative interpretations, where history trainees and history educators are actively engaged in the pedagogical process, are critical for successful online spaces.

Social- emotional stress at home:

The participants felt challenged by social and emotional stress (distractions) while at home. They were stressed, anxious and demotivated to learn since they feared getting infected with the COVID-19 virus. This is reflected in the representative comments below.

I have lost several relatives and friends to the COVID-19 disease. It is very hard for one to concentrate with studies if one's status is not known and yet one keeps interacting with community members. COVID-19 has brought too much uncertainty, we really need God's intervention. (Participant 2.7)

While another pre-service teacher retorted that,

When you are at home, you have access to many more distractions such as constant visits from neighbors, community members, announcements of death and increase in COVID-19 cases on radios. Studying from home is exhausting. This is worsened by circulation of inaccurate information by fellow students through the WhatsAppgroups. (Participant 2.9)

While the qualitative sentiments suggest that, learning during the COVID-19 pandemic was constrained through distractions from home communities, the indings contrast with literature by Ssenkusu et al. (2021) and Pokhrel and Chhetri (2021) that presents the COVID-19 pandemic as an opportunity for educational institutions, families and communities to adapt unofficial pedagogies in terms of indigenous learning from home while participating in family, community and agricultural activities.

Financial constraints:

Financial constraints are often accompanied with a lack of basic needs such as food to cater for family members during the COVID-19 lockdown.

I can no longer engage in part-time teaching to earn money. My parents cannot work during this COVID-19 lockdown. We are financially constrained; at times, we have one meal a day other times we fail to get a meal. Besides, we have not received food from the government in our home; I cannot learn anything under such hard conditions. (Participant 2.3)

The findings suggest challenges offinancial hardships and lack offood as a basic need, which affected pre-service teachers' concentration in online learning. The above findings and sentiments are in conformity with Aguilera (2020) who found that, emotional challenges and financial hardships were major bottlenecks during the COVID-19 pandemic. Dlamini (2020) put forward that, the lockdown of schools and higher education institutions in Eswatini ushered in uncertainty, fears of income losses and isolation within staf and student communities which afected the quality of online teaching. Correspondingly, Ssenkusu et al. (2021) recommends engagement in indigenous knowledge of agriculture, food production, cookery and animal husbandry to address the challenge of inancial constraints and cater for food during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ssenkusu et al. argue that the pandemic created opportunities and sustained time for students to stay with their families and communities to engage in multitasking roles of agriculture to sustain their living and online learning.

Lessons learnt from teaching and learning history education at the School of Education, Makerere University during the COVID-19

There is a need for the continuous capacity building and training of pre-service history teachers and teacher educators on the integration of ICT in history education, ushered in by the new normal. Continuous training could lead to improved ICT skills, a change of attitude, mindset and the transformation of teaching and learning practices to accommodate innovative pandemic pedagogies (Ssenkusu et al., 2021) in history education. Equally, History educators should embrace discipline speciic ICT tools such as mobile phones, WhatsApp, Zoom, Telegram, Google meet, Google docs, Voki, Screen- O-matic, Open Educational Resources and LMS with chat functions, discussion forums, wikis, blogs, big blue buton, to cater for varied learning styles. Discipline speciic ICT tools that require limited data to support continuous communication, active engagement, learner-centeredness and inquiries about the past are vital for a successful History Education online environment (Bunt, 2021).

Teacher Education programmes have to alter the way they train teachers to accommodate an online/blended learning approach in the new normal in order to prepare pre-service history teachers to transfer content knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge to their future students. The new normal, dominated by technology and blended learning, requires history education to transform to online and learner- centred pedagogy to blend with the traditional pedagogical approaches. This therefore requires history educators to engage in proper planning, preparations, development of online content, interactive activities, ICT infrastructure and support policies of online/blended learning approaches. Accordingly, Atmojo and Nugroho (2020) and Bunt (2021) recommend proper planning with flexible deadlines, as history educators require more time to carry out a series of interactive activities, to keep pre-service teachers motivated and engaged to stay online, unlike in the normal physical classroom.

In the new normal, Higher Education institutions and schools should organise with telecommunication companies to have all the institutional portals available to the students at zero rated data/charges for educational purposes. Additionally, to promote online learning during the COVID-19 lockdown and beyond, educational institutions should liaise with computer manufacturers on the possibility of obtaining affordable, yet good quality, laptops for students that can be paid of on a hire purchase basis over an agreed period. This will increase availability and ease of access to ICT infrastructure for educational purposes. The government must also invest in ensuring affordable access to the internet to support online education.

The digital divide in Uganda highlights an enormous inequality gap. This is reminiscent among the pre-service teachers as the highlighted challenges such as ICT constraints, unreliable electricity power supply, digital illiteracy and inancial constraints continue to widen the education gap between the privileged and the deprived. The use of context speciic tools such as radio, television, tax-free internet packages, print media and mobile phones, accessible to students and educators, might be a powerful way of bridging the digital divide in the education sector and also reach out to rural areas (UNESCO, 2020 ; Czerniewicz, 2020).

LMS such as MUELE ought to be user-friendly for students and faculty members. There is a need for downloadable guidelines and for personnel to offer technical guidance to students to ease access and login to MUELE. There is also a need for an online training manual and guide for use by staff and students. MUELE user guide (content), short introductory video clips, ICT support desk and an online play space (without strict rules and structures but for trial and errors) should be created on the LMS to address technical challenges as well as facilitate students' acclimatisation with online learning spaces.

Conclusion

The coronavirus pandemic highlights the ongoing need for online and blended approaches in history education to avoid total curriculum disruption and the difficulties of studying at home. Consequently, teacher education institutions and schools may need to transform their ways of teaching and learning history to accommodate deeper and meaningful learner-centred approaches in the new normal. This demands that institutions ensure that history educators and pre-service history teachers undertake constant professional trainings in online pedagogical strategies, digital literacy and obtain support to secure adequate technology and bandwidth (Dlamini, 2020). The key lesson learnt is for students to learn to engage with offline downloadable print learning materials, and discipline specific low-end technologies that require limited data packages in history education. It is hoped that such technologies will partially overcome pandemic challenges such as of ICT infrastructure, and internet connectivity. Although this research is limited to Makerere University, particularly the History Education Unit, following the narrative inquiry of researcher experience and case study of pre-service history teachers' narratives and reflections on History Education during the Covid-19 pandemic; it provides insights that can strengthen the pedagogical terrain and universities' collective response to COVID-19 in the new normal and into the future. There is need for a more extensive study to establish how these qualitative findings relate to wider contexts in university settings.

References

Aguilera, P 2020. College students' use and acceptance of emergency online learning due to COVID-19, International Journal of Educational Research Open. [ Links ]

Ali, R & Abdalgane, M 2020. Teaching English literacy in the time of COVID-19 pandemic in higher education: a case study in Saudi Qassim University. Multicultural Education, 9(5):204-215. [ Links ]

Allen, J, Rowan, L, & Singh, P 2020. Teaching and teacher education in the time of COVID-19. Asia- Pacific Journal, 48(3):233-236. [ Links ]

Atmojo, AEP & Nugroho, A 2020. EFL classes must go online! Teaching activities and challenges during COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. Register Journal, 13(1):49-76. [ Links ]

Bentrovato, D & Wassermann, J (eds.), 2021. Teaching African History in Schools: Experiences and Perspectives from Africa and Beyond. Brill Sense. Leiden Boston. [ Links ]

Bongomin, F, Olum, R, Nakiyingi, L, Lalitha, R, Ssinabulya, I, Sekaggya-Wiltshire, C, & Byakika-Kibwika, P 2021. Internal medicine clerkship amidst COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study of the clinical learning experience of undergraduate medical students at Makerere University, Uganda. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 12: 253-262. [ Links ]

Bryman, A 2012. Social Research methods (4th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press [ Links ]

Bunt, B 2021. Online teaching in education for the subject group History under COVID-19 conditions. Yesterday & Today, (25):1-26. [ Links ]

Clandinin, DJ 2006. Narrative inquiry: a methodology for studying lived experiences. Research Studies in Music Education, (27):44-54. [ Links ]

Crawford, J, Butler-Henderson, K, Rudolph, J, Malkawi, B, Glowatz, M, Burton, R, & Lam, S 2020. COVID-19: 20 countries' higher education intra-period digital pedagogy responses. Journal of Applied Learning & Teaching, 3(1):1-20. [ Links ]

Czerniewicz, L 2020. What we learnt from "going online" during university shutdowns in South Africa. Available at https://philonedtech.com/what-we-learnt-from-going-online-during-university-shutdowns-in-south-africa. Accessed on 20 October 2021. [ Links ]

Dlamini, R 2020. A reflection on History education in higher education in Eswatini during COVID-19. Yesterday & Today, (24):247-256. [ Links ]

Dogar, AA, Shah, I, Ali, SW, & Ijaz, A 2020. Constraints to online teaching in institutes of higher education during pandemic COVID-19: a case study of CUI, Abbotabad Pakistan. Revista Romaneasca Pentru Educatie Multidimensionala, 12(2Sup1):12-24. [ Links ]

Ezati, B, Sikoyo, L, & Baguma, G, 2020. COVID- 19 and learning from home: parental involvement in learning of primary school age children. Dissemination Workshop held on 21 December 2020 at Esella Hotel, Kampala Uganda. [ Links ]

Guyver, R 2013. History teaching, pedagogy, curriculum and politics: dialogues and debates in regional, national, transnational, international and supranational setings. International Journal of Historical Learning Teaching and Research, 11(2), 3-11. [ Links ]

Huang, RH, Liu, DJ, Tlili, A, Yang, JF, & Wang, HH 2020. Handbook on facilitating lexible learning during educational disruption: the Chinese experience in maintaining undisrupted learning in COVID-19 Outbreak. Smart Learning Institute of Beijing Normal University UNESCO, 1-54. Retrieved from: https://iite.unesco.org/news/handbook-on-facilitating-lexible-learning-during-educational-disruption/. [ Links ]

Kabugo, D 2020. Utilizing open educational resources to enhance students' learning outcomes during the COVID- 19 schools lockdown: a case of using Kolibri by selected government schools in Uganda. Journal of Learning for Development- JL4D, 7(3):447-458. [ Links ]

Mahaye, NE, 2020. The impact of COVID- 19 pandemic on education: navigating forward the pedagogy of blended learning. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Mahaye-Ngogi-Emmanuel/publication/340899662_The_Impact_ofCOVID 19Pandemicon_South_African_Education_NavigatingForward_the_Pedagogyof_Blended_Learning/links/5ea315ae45851553faaa31ae/The-Impact-of-COVID-19-Pandemic-on-South-African-Education-Navigating-Forward-the-Pedagogy-of-Blended-Learning.pdf. Accessed on 20 October 2021. [ Links ]

Makerere University, Academic Registrar 2021. Completion of Examinations for Semester 1 2020/2021. Available at https://news.mak.ac.ug/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Completion-of-Examinations-for-Semester-I-20202021.pdf. Accessed on 25 October 2021. [ Links ]

Miles, M, Huberman, M & Saldana, J 2014. Qualitative data analysis, a methods source book, 3rd edition. London: Sage Publication. [ Links ]

MoES 2020, Ministry of Education and Sports framework for provision of continued learning during the Covid-19 lockdown in Uganda. Available at http://planipolis.iiep.unesco.org/en/2020/uganda-covid-19-education-sector-response-guidelines-6931. Accessed on 28 October 2020. [ Links ]

Mokoena, S 2013. Engagement with and participation in online discussion forums. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology-TOJET, 12(2):97-105. [ Links ]

Moser, A & Korstjens, I 2018. Series; practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis, European Journal of General Practice, 24: (1): 9-18. [ Links ]

Nabukeera, MS 2020. COVID-19 and online education during emergencies in higher education. Available at http://ir.iuiu.ac.ug/xmlui/handle/20.500.12309/732. Accessed on 28 October 2020. [ Links ]

Nawangwe, B, Muwagga, AM, Buyinza, M, & Masagazi, FM 2021. Reflections on university education in Uganda and the COVID-19 pandemic shock: responses and lessons learned. Alliance for African Partnership Perspectives, 1(1):17-25. [ Links ]

New Vision, 2020. Universities to embrace the e-learning approaches as an intervention to COVID-19. Available at https://www.newvision.co.ug/. Accessed on 29 October 2020. [ Links ]

Olum, R, Atulinda, L, Kigozi, E, Nassozi, DR, Mulekwa, A, Bongomin, F, & Kiguli, S 2020. Medical education and e-learning. during COVID-19 pandemic: awareness, atitudes, preferences, and barriers among undergraduate medicine and nursing students at Makerere University, Uganda. Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development, 7, 1-9. [ Links ]

Parkes, J, Datzberger, S, Howell, C, Kasidi, J, Kiwanuka, T, Knight, L, Nagawa, R, Naker, D, & Devries, K 2020. Young people, inequality and violence during the COVID-19 lock down in Uganda. Institute of Education, University of London. Available at https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10111658/1/Young%20People%20COVID%20lockdown%20Uganda.pdf. Accessed on 29 October 2020. [ Links ]

Pokhrel, S, & Chhetri, R 2021. A literature review on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on teaching and learning. Higher Education for the Future, 8(1):133-141. [ Links ]

Sali, S. 2020. Gender, economic precarity, and Uganda government's COVID-19 response. African Journal of Governance and Development, 9 (1.1): 287-308. [ Links ]

Ssenkusu, P, Ssempala, C & Mitana, JM 2021. How Covid-19 pandemic might lead to appreciating pedagogies driven by the multiplicity of intelligence: a case of the Ugandan experience. International Journal of Educational Research Review, 6(4):355-368. Available at https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/ijere/issue/64800/1012374. Accessed on 29 October 2020. [ Links ]

Tumwesige, J 2020. COVID-19 educational disruption and response: rethinking e-learning in Uganda. Konrad Adenauer Stiting. Available at: https://www.kas.de/documents/280229/8800435/COVID-19+Educational+Disruption+and+Response+-+Rethinking+e-Learning+in+Uganda.pdf/6573f7b3-b885-b0b3-8792-04aa4c9e14b7?version=1.0&t=1589283963112. Accessed on 29 October 2020 [ Links ]

UNESCO 2020. COVID-19 educational disruption and response. Available from https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse. Accessed on 30 October 2020. [ Links ]

Yin, R 2009. Case study research (Volume 5.). London: Sage Publication. [ Links ]