Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Yesterday and Today

On-line version ISSN 2309-9003

Print version ISSN 2223-0386

Y&T n.26 Vanderbijlpark Dec. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2223-0386/2021/n26a6

ARTICLES

Silenced and Invisible Historical Figures in Zambia: An Analysis of the Visual Portrayal of Women in Senior Secondary School History Textbooks

Edward Mboyonga

Higher Education and Human Development Research Group, University of the Free State, South Africa. emboyonga85@gmail.com Orcid: 0000-0002-6928-3972

ABSTRACT

Despite their significant contribution to the country's historical development, women's influence is commonly underestimated and ignored in Zambian history literature. Subsequently, their role remains undocumented in secondary school textbooks to the extent that the sex blindness of traditional historiography, which sustains male dominance in history, remains unchallenged in the books. Through a qualitative approach and purposive sampling of two Zambian secondary school Grade 12 learners' history textbooks, the study examined the portrayal of women. Located within the decoloniality paradigm, it counters the coloniality of power manifested through the insularity of dominant patriarchal historical narratives entrenched in the secondary school history curriculum, largely reflecting the remnants of colonial epistemologies and historiographical traditions. The findings in both textbooks reveal that the female characters are silenced and invisible compared to their male counterparts, reflecting the patriarchy hegemony in the secondary school Zambian history curriculum. In decolonising colonial power manifested in the curriculum, the study recommends mainstreaming gender equality in the history curricula and teaching and learning materials, mainly the learners' textbooks, to reflect women's achievements.

Keywords: Decoloniality; Visual images; Gender; History textbooks; Secondary school; Women; Zambia.

Introduction

Since the launch of the 1995 Beijing Platform for Action in ensuring gender equality, the world has made great strides towards the realisation of gender equality (UNICEF, 2020). Zambia has made steady progress in empowering women in education, sports, military, engineering, and politics. Over the past decade, the country has witnessed an unprecedented rise in female leaders serving in influential national positions. Among the notable women are Inonge Wina, the first female Republican Vice President; Nelly Mutti, the first female Parliament Speaker; Stella Libongani, the first female Inspector General of the Zambia Police Service; Justice Irene Mambilima, the first female ChiefJustice and Prof Hildah Ngambi, the first female Vice-Chancellor at a public university. While this development is heralded as a big step in promoting female involvement in governance, history shows that their influence in leadership is not limited to the contemporary period. Women's participation in influential leadership roles dates as far back as the pre-colonial era. For instance, through its podcasts entitled Leading Ladies, the Women's History Museum of Zambia documented how women in pre-colonial Zambia held significant leadership positions in military, politics, peace-making, and religion, among others from the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries (Samanga, 2019). However, despite their significant contribution to the country's historical development, women's influential role is commonly underestimated and ignored in Zambian history literature.

Several scholars have highlighted that textbooks continue to perpetuate patriarchy by silencing the historical roles played by women (Schocker & Woyshner, 2013; Chiponda & Wassermann, 2015; Nasibi, 2015). Textbooks continue to perpetuate gender stereotypes in aspects of images, text, and the selection of topics. This paper builds on such arguments and advocates for the need to decolonise power and knowledge in textbooks by recognising women as equally important historical agents. Globally, there have been various efforts in addressing gender issues in learning materials, such as revision and assessments of curricula, textbooks, teacher training materials, and teaching practices (Blumberg, 2007; UNESCO, 2016).

In 2012, the Zambian government introduced a new curriculum framework that recognised gender as one of the primary cross-cutting issues in education and called for gender sensitivity in learning materials and pedagogies as per the National Gender Policy of 2000 (Ministry of Education (MOE), 2013). With these curriculum reforms, it was envisaged that the learning and teaching materials like charts, textbooks, and posters would be free from gender biases. Accordingly, the new curriculum led to revising the learners' textbooks for both primary and secondary schools. Schools have also been called upon to address gender issues of equity and equality in the curriculum by embracing gender-sensitive teaching methodologies in the provision of education (MOE, 2013). However, there is limited empirical knowledge on the gender sensitivity of the textbooks currently being used in Zambian secondary schools. To date, there is a shortage of scholarly data on the aspects of gender and history in the senior secondary school curriculum, despite the significant breakthroughs of women and their contribution to Zambia's historical development. Against this background, this study seeks to bridge this gap by examining the portrayal of women characters in selected senior history textbooks in Zambia. In so doing, this article contributes to addressing what Chiponda (2014) identifies as a critical lack of research on the portrayal of women in history textbooks in the African context.

Research objectives and questions

The study's main objective is to examine the representation and portrayal of female characters in senior secondary school history textbooks and specifically examine women's visual presentation in two Grade 12 Zambian history textbooks. Accordingly, the following three questions are posed:

i. How are women represented numerically through visual images in senior secondary school history textbooks in Zambia?

ii. How are women portrayed in visual images in the senior secondary school history textbook in Zambia?

iii. What are the implications of the visual portrayal of women in history textbooks to the learners in Zambia?

Literature review

History teaching and value formation in learners

The teaching and learning of history play a critical role in understanding historical developments in society and value formation among the learners. History equips individuals with the knowledge of understanding the course of change in their communities and continuity in human affairs (Kabombwe, 2019). In this way, history highlights how societies have evolved in social, political, and economic development and may help us understand how past occurrences have shaped current events. History may help the learners develop the aptitude to evaluate existing social, political, economic, and cultural challenges and offer possible solutions (Ministry of Education, Science, Vocational Training and Early Childhood Education (MOESVTE, 2013). In her blog entitled "Why Teaching of History is Important?" Osleen (2019) further echoes the vital role history plays in fostering historical knowledge and value formation where she states that "history's value lies in how to apply the lessons from past to our present and future". Osleen argues that the application of history is significant for the learners in that they will acquire specific values based on the historical bodies of knowledge exposed to them.

Additionally, history offers the learners a valuable opportunity to learn about some of the historical figures that had played instrumental roles in shaping the history of their societies in different spheres (Osleen 2019; Mburu & Nyaga, 2012). It offers a platform through which the learners study the lives of individual leaders who shaped history. For example, by evaluating why particular leaders made certain decisions, history puts the learners in the shoes of past leaders and challenges their decision-making capabilities. This function of history may make learners appreciate and hero-rise inspirational leaders as they get inspired and seek to walk in the shoes of such leaders. It is imperative in the Zambian context, where history has been envisioned as a subject that can equip learners with values such as reflection, bravery, appreciation, courage, and patriotism, among others (MOESVTE, 2013). It is no wonder that history has been an essential aspect of most leadership and public service courses in many institutions in Zambia.

In line with the social functions of education, the teaching of history is central in the inculcation of Ubuntu norms (Chimbunde & Kgari-Masondo, 2021). For instance, the Zambian history syllabus aims to foster the values of compassion, reciprocity, dignity, teamwork, harmony, forgiveness, and other humane tenets among the learners (Kabombwe & Mulenga, 2019; MOESVTE, 2013). Hence, history is deemed significant in upholding society's ethical and moral fabrics crucial for building and sustaining justice and mutual care. In this vein, history may help the learners be rooted in their environment by gaining knowledge that does not alienate them from their culture.

Furthermore, in this era of globalisation, history is the vehicle through which the young generation gets connected with the world (Osleen, 2019). Teaching history in schools also expands the global outlook of the learners since they learn histories of different geographical regions and periods. While history is instrumental in value formation, it is worth recognising that values are not universal. History can also teach negative values that might sustain hegemony based on race, gender, religion, or economic status. In this light, it suffices to conclude that history plays an essential role in society, so it should not be taught in a manner that may perpetuate negative values in the minds of young learners (Bentrovato, Korostelina & Schulze, 2016; Bentrovato, 2017).

History textbooks and gender

There is a consensus in the literature that learners' textbooks reflect the curricula, which ultimately, in terms of gender, shapes the understanding of social and historical roles of men and women in society (Blumberg, 2007 & 2008; Alayan & Al-Khalidi, 2010; Chiponda & Wassermann, 2011& 2015; Atchison, 2017; Bair, 2020). In elaborating the significance of textbooks in learning, Chiponda and Wassermann posit that the "ideologies of society are kept in the form of [an] organised body of knowledge through textbooks [hence] they can canonise the social norms of the society" (2011:23). Given this, when it comes to influencing gender norms in society, one should not underestimate the value of textbooks. Furthermore, particularly in their formative years, the learners are bound to be highly influenced by what they see and read in textbooks. Indeed, what children learn in their formative years has a profound influence throughout the lives of their learners, more especially in influencing their value systems (Alayan & Al-Khalidi, 2010). Therefore, textbooks must be produced with a gender perspective to provide all learners with a balanced and gender-sensitive education.

In locating the nexus between history textbooks and gender, a plethora of studies has shown that textbooks are crucial in shaping gender roles in the minds of learners (Chick, 2006; Blumberg, 2007; Mutekwe & Modiba, 2012; Chiponda, 2014; Chiponda & Wassermann, 2011 & 2015; Acheson et al., 2020). Collectively, these studies have pointed out the role of history textbooks as agents of the hidden curriculum that may reinforce patriarchal values in schools. As part of the hidden curriculum, the textbooks serve as a medium for learners to pick up different gendered and patriarchal values, subtly conveyed in schools (Mutekwe & Modiba, 2012) and transmitted across different generations (Alayan & Al-Khalidi, 2010). Therefore, textbooks remain an essential blueprint in the lives of school learners, a reason not to underestimate their influence in the acquisition of gender norms among school-going children.

One of the critical aspects of the textbook, which is also central to the current study, is visual images, which serve as an essential aid in ensuring effective teaching and learning in a classroom. The use of graphical images in education owes much to the Moravian philosopher John Amos Comenius (1592-1670). In 1658, the Orbis Pictus, a pioneering textbook in using pictures for illustrations when teaching, was published by Comenius (Szórádová, 2015). He contended that visual images in textbooks are significant in helping learners perceive the object and the phenomena in the syllabus through illustrations. Similarly, Chiponda and Wassermann (2015) also note that visual images in textbooks help learners form a fundamental symbiotic relationship with the written text. They argue that "in History textbooks, therefore, visual images render human experiences less abstract" (2015:208). In this regard, the significance of visual images in the pupils' learning experiences and their influence in shaping learners' perceptions of gender norms should not be underestimated.

Literature is replete with evidence that women are underrepresented in history textbooks in both written text and visual images in many countries. For instance, a study on gender and agency in history and civics in Jordan and Palestine established that "men are consistently named as prominent figures in the shaping of history, and defence of the state, in leading positions characterised with valour and bravery, and as leaders, influential persons, clerics, and scholars" (Alayan & Al-Khalidi, 2010:33). Similarly, studies on gender sensitivity of secondary school history textbooks in the USA (Chick, 2006; Schocker & Woyshner, 2013), Malawi (Chiponda, 2014; Chiponda & Wassermann, 2011, 2015), Kenya (Nasibi, 2015), South Africa (Schoeman, 2009) and Zimbabwe (Dudu et al., 2008) have all pointed to the over-representation of male characters.

The aspect of gender representation in history textbooks is underexplored in Zambia. Instead, studies have focused on teacher involvement in curriculum development (Mwanza, 2017), integration of digital technologies in teaching social studies (Mboyonga, 2019) and implementing a competency-based curriculum in history (Kabombwe, 2019; Kabombwe & Mulenga, 2019). A common finding across these studies is that curriculum development in Zambia is based on a horizontal approach that limits teachers' meaningful engagement in the process. Musilekwa (2019) analysed the development of learners' textbooks for Junior Secondary following the integration of civics, history, and geography into a single subject called Social Studies. The study revealed that textbook production in Zambia is affected by political influence, lack of national textbook policy, profit motives, and inadequate quality assurance process. However, like the previous studies, Musilekwa's (2019) study did not highlight the gender perspectives in the textbooks, a premise for my study.

A decolonial theoretical perspective

In analysing the visual portrayal of women in senior history textbooks in Zambia, the study is theoretically situated within the decolonial framework. I drew on decolonial theory because the study addresses the patriarchal historical narratives that marginalise women's contribution to history. According to Gebriel (2018:21), "decolonial workers in the academia have for years sought to bring the marginalised to the centre-stage of scholarly labour; to memorialise and elevate their perspectives, histories, and struggles, which would otherwise be lost in the throes of oppression". At issue is that knowledge is power. By not teaching the significant role women playing shaping our history, we deny them their agency as contributors to history. Therefore, the secondary school curriculums must shift from the current forms of historical discourses advancing coloniality of power through dominant man-centred history writing, and move towards decolonising knowledge by highlighting women's contribution in shaping the country's history.

Concerning teaching history at the secondary school level, decoloniality entails questioning whose power, ideology, and knowledge have been advanced in the curriculum and through the learners' textbooks. To this end, studying the portrayal of female characters within a decoloniality framework enables us to "reflect on what kinds of historical knowledge about women are considered 'legitimate' by the curriculum, and to evaluate how this knowledge sustains or challenges an otherwise androcentric or masculinist history" (Wills, 2016:22). Indeed, this is instructive in the Zambian case, whereby the dominant historical narratives have continued to neglect and discount the contributions of women. In doing so, decolonial discourses help us counter the coloniality of power manifested through the insularity of the dominant patriarchal historical narratives entrenched in the secondary school history curriculum, which are remnants of colonial epistemologies and historiographical traditions. The coloniality of power refers to the legacies of European colonialism in knowledge, social forms, and institutions like universities and schools (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2013). In the case of secondary school resources like learners' textbooks, coloniality of power is conveyed through unbalanced gender power relations in the contents of such books.

While gender inequalities in Africa manifested through indigenous cultures during the pre-colonial period, European influence exacerbated it (Anunobi, 2002). In particular, European colonisation of the continent "undermined sources of status and autonomy that women had and strengthened elements of indigenous male dominance or patriarchy" (Anunobi, 2002:43). Before colonialism, women, especially in matrilineal societies, held political positions such as chiefs, advisors, or rainmakers, which were part of their power sources. However, with the advent of colonialism in Africa, male-dominated government structures were introduced that did not recognise women's role in governance. Additionally, the colonial forms of religion, education, and economy which they introduced heightened patriarchy by undermining women's indigenous sources ofpower and further isolated them from active participation in the socio-economic and political activities of their societies (Anunobi, 2002; Jaiyeola & Aladegbola, 2020; Spencer-Wood, 2016).

Nelson Maldonado-Torres, a leading decolonial scholar, has highlighted that colonial practices manifest in various knowledge domains in Africa, including textbooks. In buttressing his views, he argues that "it is maintained alive in books, in the criteria for academic performance, in cultural patterns, in common sense, in the self-image of peoples, in aspirations of self, and so many other aspects of our modern experience" (Maldonado-Torres, 2007:243). These views resonate with the formal education system in Zambia and much of Africa, which exists in the form of transplanted learning institutions where the curriculum replicates colonial systems of power hegemony that negate the contribution of women. For instance, the development of learners' textbooks in Zambia is traced to colonial periods when the Catholic Church established a missionary press that printed different literature in churches and schools (Musilekwa, 2019). However, the content of most history books produced at that time reflected the patriarchy exacerbated by the missionary church groups and the British government (Sharma, 2019). In this regard, the presence of patriarchal undertones in the Zambian history curriculum, five decades after independence can be explained aptly in the words of Mulenga Kapwepwe, a co-founder of the Women's History Museum of Zambia, who stated that:

Pre-colonial Zambia was 80 per cent matrilineal and matriarchal, but this was changed to patriarchal rule by British colonisers and Christian missionaries. Many women chiefs were either ignored or not recognised by the colonial government, who were now keeping the historical records. The patriarchal biased system continued after the colonial period, and post-colonial historians took up and maintained the male perspective of history. Oral history has kept female history, but little of it made its way to print or schools (Kapwepwe cited in Sharma, 2019).

Based on the above, there is an urgent need to address the various aspects of coloniality in Zambian history narratives by bringing on board the knowledge of the silenced ones. When considering the significance of learners' textbooks in legitimising the curriculum, it is imperative to address the coloniality of power and knowledge in secondary school books, charts and other educational material that conveys various forms of historical knowledge. Doing so requires the representation of the marginalised groups in society whose voices and agency in history curricula are often disregarded based on race, physical abilities, or gender. In addressing the coloniality of power in secondary school learning material, "gender should be an essential consideration for a decolonised curriculum" (Wills, 2016:22). Therefore, applying a decolonial perspective to examining the visual portrayal of women in senior history textbooks in Zambia would help highlight how the patterns of power and knowledge productions have been maintained in the learners' textbooks.

Methodological approach

The study adopted a qualitative inquiry through a purposive sampling of two senior history Grade 12 textbooks. A qualitative investigation is more suitable for a study seeking a deeper exploration of an issue (Bryman, 2012; Creswell, 2007; Merriam & Tisdell, 2015). The approach was deemed relevant for studying how women are portrayed in history textbooks and gaining a detailed understanding of gender and curriculum in the Zambian context. The choice of a qualitative inquiry was further informed by earlier studies that have analysed the pictorial representation of women in textbook books and have since argued for its use in gaining an in-depth understanding of the phenomenon (Chiponda, 2014; Chiponda & Wassermann, 2011 & 2015; Acheson et al., 2020). The sample for the study comprised all visual images containing people in two Grade 12 history textbooks approved for use in Zambian secondary schools by the Ministry of Education. The textbooks selected are:

• Assa Okoth, Agumba Ndalo & Jason Mashwekwa (2017). Achievers senior secondary history learner's book, 12. Lusaka: East Africa Educational Publishers Ltd.

• David Sikanyiti (2017). Excel and advance in history: learner's book, Grade 12. Lusaka: Grey Matter Ltd.

The above textbooks were purposively sampled based on three factors. Firstly, they are approved for use in Zambian secondary schools by the Curriculum Development Centre (CDC). Due to the adoption of liberal policies in service provision, the textbook development process in Zambia is mainly in the hands of private authors or publishers who develop textbooks according to the given guidelines (Ministry of Education, 1996). The approval by the CDC implies that the selected texts are up to standard for usage, having met the set requirements for textbook production in Zambia. Ideally, all schools are supposed to use the prescribed textbooks where they are available.

Secondly, I selected the case study texts because they were the first two Grade 12 history textbooks produced according to the New Curriculum Framework of 2013. While secondary schools use many books, most did not meet the study's criteria because they were written before implementing the curriculum. The Ministry of Education distributed the two textbooks in all public secondary schools to implement the new curriculum. In fact, according to the authors of the Achievers senior secondary history learner's book, 12, the textbook was developed to cover the new senior secondary school syllabus. It does so by fulfilling the aims and objectives outlined in the revised history syllabus (Okoth, et al., 2017).

Thirdly, the two textbooks are the commonly used reference resources in teaching Zambian history at the senior secondary school level. Each senior grade has a specific focus regarding the thematic focus of history coverage. The Grade 11 textbooks focus on world history from 1870 to the present, whereas Grade 10 textbooks focus on the history of Southern Africa. Southern African history in the Zambian history secondary school syllabus predominantly covers the history of South Africa with few topics on Lesotho, Swaziland, Namibia, Botswana, Angola, and Mozambique. Thus, I deliberately chose Grade 12 textbooks because Zambian history is taught at that level as part of Central African history, which comprises Malawi and Zimbabwe's history.

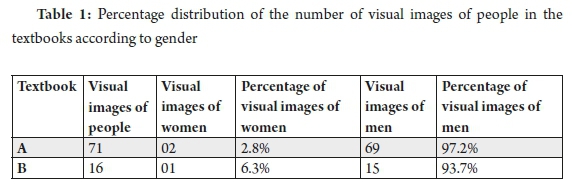

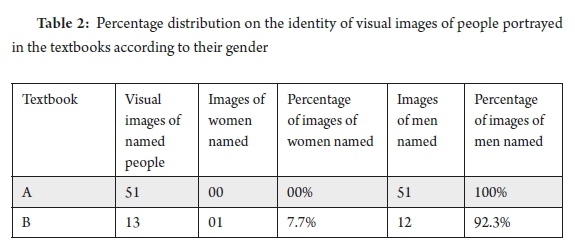

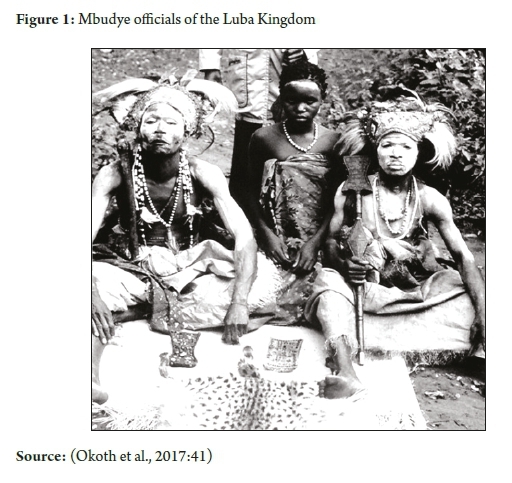

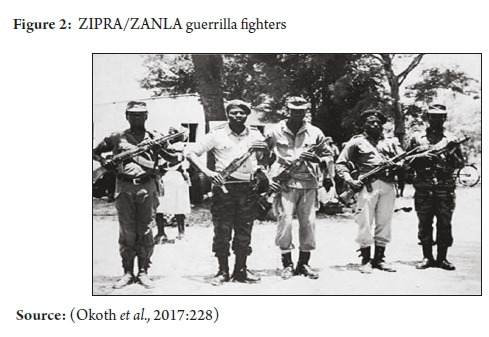

In terms of data analysis, the study employed content analysis in analysing the visual images of human characters in the two textbooks. The research implied a systematic analysis of physical tallying (see Tables 1 & 2) of all the clear visual images of people in the textbooks by counting how many female characters were portrayed in each book compared to the male characters. It also allowed the identification of those characters in terms of their names and their role in history. In this regard, the units of analysis included all the visual images of people and names associated with the said images in the textbooks. By interpreting the meaning of the graphic images, I drew on the decolonial theoretical paradigm to understand the importance of images by asking what type of knowledge they present and represent and how that can impact the learners. It enabled me to interpret how women are portrayed in terms of identity, numerical interpretation, and occupation compared to men. Based on the physical tallying of the visual images, frequencies and percentages of images according to gender were employed to analyse the data. I also inserted the picture captions depicting the female characters to enrich the findings (Figures 1, 2 & 3). For easy analysis, the first textbook authored by Okoth et al. (2017) I will refer to as Textbook A, whereas Excel and advance in history: learner's book, Grade 12 by Sikanyiti (2017) will be referred to as Textbook B.

Findings of the study

The portrayal of women in the visual images in the senior secondary history textbooks

The findings on women's numerical representation in visual images in the two textbooks appear in Table 1 below.

From the table above, it is evident that women are underrepresented in the two history textbooks. In Textbook A, there are seventy-one (71) visual images of people. When analysed according to gender, there are sixty-nine (69) pictures for male characters translating to 97.2% against two (2) for females, which amounts to 2.8%.

Furthermore, women characters in Textbook A are portrayed as submissive and timid compared to the authoritative display of men, thereby perpetuating patriarchal authority in learning materials. In the first image, on page 41 of the textbook, an unknown young woman is shown in the company of two (2) Mbudye male officials of the Luba Kingdom; the book does not capture the role woman played (Figure. 1). Learning about the Luba Kingdom for Grade 12 learners in Zambia provides them with the prerequisite knowledge for understanding the origins of most ethnic groups in the country. In the Luba Kingdom, the Mbudye officials were responsible for maintaining the oral histories of kings, their villages, and the land's customs. Even though these officials were men, they believed that the king was a "woman", because the first royal diviner was a woman (Roberts, 2013). Among the pre-colonial Luba society, it was recognised that spiritually, the source of political power came from women, but this was disrupted by the advent of Belgium colonialism which opposed such practices (Roberts, 2013). Considering that several Zambian ethnic groups migrated from the Luba Empire, the revised textbooks needed to highlight the role of women in the pre-colonial political systems. Such historical knowledge may offer new insights and challenge the current male-centred historical narratives, often presented to the learners in Zambian schools.

The second female character is also unknown and depicted as a spectator of the male military heroes of the Zimbabwean liberation struggles (Figure.2). In this regard, the military is portrayed to the learners as the sphere of men, and women's involvement in the liberation struggles is invisible. The prominence of male figures in history is also reflected in Textbook B, where out of the sixteen (16) visual images of people in the textbook, fifteen (15); 93.7% are male, whereas one (1); 6.3% is female.

In the second analysis, the study sought to determine how female characters are portrayed in terms of identity through names concerning their male counterparts. The findings are presented in the table below.

The above table shows that more male figures are identifiable by their names and roles than women. In textbook A, all the images of the named historical characters are men, translating into a 100% identification for male characters with no single female character named. In Textbook B, out of the thirteen images of the named people, there are twelve (12); 92.3% male characters and only one (1); 7.7% identifiable female figure, namely Joyce Banda, the former president of Malawi and Africa's second female republican president between 2012 and 2014 (See figure 3). While this can be deemed a significant step in documenting the success of women in contemporary politics, it is still overshadowed by the dominant visual images of men in textbooks. Across the two textbooks, only one-woman leader is portrayed in the visual images compared to the sixty-three images of male political figures. Strikingly, there are no Zambian female historical figures included in both texts.

The above findings collectively suggest that the secondary school history learners in Zambia are not exposed to the contribution of women in their society either during the pre-colonial period or the post-colonial era. The following section discusses the findings drawing on the implications of gender-blind textbooks on learners' value formation and aspirations. The section further addresses the results within the current discourses of decolonisation of power and knowledge.

Discussion of the findings

Portrayal of women in visual images

This study revealed that gender biases in Zambian secondary school history textbooks are prominent, as evidenced by the over-representation of male characters in visual images.

The findings are in sync with other studies that have established that women's contribution to history is often underrepresented in learner's textbooks (Chick, 2006; Schoeman, 2009; Schocker & Woyshner, 2013; Chiponda & Wassermann, 2015; Nasibi, 2015). Through the dominant images of male characters in the textbooks understudy, coloniality of power is conveyed by portraying men at the centre of historical knowledge, whereas the role of women as essential agents in shaping history is covertly annihilated. Thus, while the few women characters in the textbooks are confined to the peripherals, we see the active role played by men in shaping history as missionary explorers, pre-colonial state builders, agents of colonisation, and heroes of African independence to modern-day politicians. An underlying factor for this is that the visual images in history textbooks focus more on Zambia's military and political history. Women's involvement in such roles became less visible with the advent of institutionalised patriarchy that was part of the British colonial education system (Sharma, 2019). The control of gender and knowledge production is what Aníbal Quijano (2007) identified as the critical contours of the colonial matrix of power. Therefore, the continued silence of the learners' textbooks on the historical roles of women embodies coloniality of power, which may reinforce stereotypes and propagate a history that can be termed as "his-story". In this regard, secondary school learners in Zambia are often presented with incomplete accounts of historical knowledge, which would otherwise be addressed by decolonising the curricula. At issue is that decolonisation is not about 'cancelling' history; instead, it is an additive process to knowledge essential for educational development (Meghji, 2021). Concerning gender equity, this entails promoting a gender-sensitive curriculum reflected in the learners' textbooks that will acknowledge the epistemic contributions of both males and females as significant agents in shaping Zambia's history.

Given that the publication of the case study textbooks was in line with the New Curriculum Framework of 2013, calling for gender sensitivity in learning materials, the evidenced under-representation of women, however, indicates that the prescribed books used in schools do not follow the curriculum framework in so far as eliminating gender biases. Thus, there is a disjuncture between the government policy of gender integration in curriculum and practice, which perpetuates gender biases in learning materials. The mere fact that policies that recognise women in history constitute an essential component of school history does not simply translate into changes at the classroom level (Schoeman, 2009). The transformation depends on various factors, such as the content of the textbooks in use and the teacher's classroom practice, among others. Based on the findings, it suffices to argue that the current packaging of the secondary school history curriculum as reflected in textbooks still epitomises the coloniality of power by sustaining patriarchal knowledge systems, which can reinforce the gender stereotypes embedded in most Zambian societies. The two textbooks are a missed opportunity for "engaging students in meaningful discussions about gender and female roles in society across cultures" (Acheson et al., 2020:127). However, this study advances that teachers could still pick up this missed opportunity and turn the lack of female visual representations into a chance to address gender issues. Teachers can act as agents of decolonising the curriculum at the classroom level by adding 'marginalised' knowledge to the current body of historical discourses.

The study demonstrates that despite revising the curriculum, promoting gender sensitivity in learning materials such as history textbooks has remained a challenge owing to the continued subversion of the historical agency of women. For instance, the Zimbabwean liberation struggle is reinforced as a hegemonic norm for male militancy. The only visible woman in the image is a mother and spectator in the background (Figure 2). There is also no mention of the role played by women during the liberation struggles in the written text, even though some women, such as Joyce Teurairopa Mujuru, had risen to command ranks in the Zimbabwe National Liberation Army (ZANLA) (Lyon, 2002). Thus, the evidence from my study supports the argument that how women are portrayed in textbooks can manifest a sexist hidden curriculum that covertly implies that women's place is in traditional domestic roles such as childbearing and rearing (Alayan & Al-Khalidi, 2010; Dudu et al., 2008).

Although Zambian women have played crucial roles as kingdom warriors, founders, religious leaders, and rainmakers during the pre-colonial era, and as active leaders in the independence struggle (Samanga, 2019), their contributions seem to have been engulfed in the "patriarchal centred curriculum" in textbooks. The concern is the absence of Zambian female characters in the visual images of people in both textbooks. The pictures that authors use usually decode the content of their books, and these books convey the curriculum contents. I argue that patriarchy in these textbooks is reminiscent of colonial knowledge. The historical sources used in producing the learners' textbooks rely heavily on nationalistic historiography, which often has side-lined women (Sharma, 2019). Revisionist historical studies in Zambia have shown women's influential role in shaping the country's history, such as the Women's league, during the independence struggles (Geisler, 1987) and Alice Lumpa Lenshina in promoting African religious beliefs (Gordon, 2008; Munga, 2016), among others. From a decoloniality discourse point of view, the current form of the Zambian history curriculum, as reflected through the visual images in the prescribed textbooks, ignores the voices and resilience of women. In so doing, it erases and silences women's achievements by not reflecting their rightful role as historical agents, thereby leading to epistemic violence of historical knowledge. By rendering women's historical agency invisible, the visual images lead to what de Sousa Santos (2007) refers to as the normalisation and privileging of some forms of knowledge, in this case, the patriarchal historiography. Given this, it is therefore imperative that we question and eliminate the exclusion and discrimination of women in existing knowledge domains as it deprives the world of other knowledge (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2019).

Implications of the portrayal of women in learners' history textbooks

Visual images in a textbook are not in a vacuum, and should not be explained in isolation because they reflect the prescribed textbooks produced to legitimatise both the written and the hidden curriculum. In this regard, "what students learn at school generally depends on ideologies about gender that are embedded in the curriculum in both explicit and hidden forms"(Mutekwe & Modiba, 2012:371). The structure and functions of institutionalised education systems aim at producing and reproducing institutional conditions through inculcation and reproduction (Bourdieu & Passeron, 1990). History textbooks can instil shared gender values and norms in the learners. In the process, these learners may acquire skills and attitudes that will sustain society by reproducing roles. Consequently, given that textbooks constitute the most important and common forms of teaching and learning resources in Zambian schools, the dominant patriarchal narrative which continues to silence female contribution in the country's history can have more profound ramifications for the learners. In light of the findings, the study argues that women's rightful place in history may not be valued among the learners because of the hegemony of the male figures, which is highly documented and pronounced in their textbooks and classes.

Additionally, since textbooks are pivotal in instilling values among the learners in secondary schools, what learners see in textbooks, may profoundly influence their career aspirations. For that reason, a gender-sensitive curriculum is critical, especially for the Grade 12 learners who are in their last year of secondary school journeys and are preparing to take up roles in the broader society. As espoused by Chiponda and Wassermann, "the way women are portrayed in history textbooks, therefore, in all likelihood influences the way the youth understand the contributions of women to history" (2011:14). It is clear that, despite the influential roles played by women in society, Zambian secondary school students are not exposed to female role models who can inspire them, even though women have played a pivotal role in shaping the country's development in many sectors. Therefore, it is not surprising that female learners may develop a low interest in politics and military careers, usually portrayed in the history textbooks as arenas for men. Broader literature also confirms that learners are more disposed to imitate characters and conduct themselves in a manner portrayed by the people of their gender in particular textbooks (Mburu & Nyaga, 2012; Mutekwe & Modiba, 2012).

Conclusion and recommendations

This study established that the patriarchal nature of the visual images in secondary school history textbooks has neglected the role of women as historical agents. Despite recognising gender equity as a cross-cutting issue in the 2013 revised curriculum, an analysis of the portrayal of women through visual images in the textbooks reveals that they remain silenced and invisible. In the two textbooks examined, there is little appreciation of the significant role played by women in the country's history, thereby exacerbating the coloniality of power in the history curriculum. If left unattended, the current man-centred historical narrative taught to the younger generations would blind them to the many achievements scored by women in the country and heighten the current status quo of trampling upon women's rights. In moving towards gender equity, there is a need to revise history learners' textbooks to reflect the contribution of women as significant agents in Zambian history. These reforms can help actualise the new curriculum's aspirations to promote gender-inclusivity in learning and teaching materials.

References

Acheson, G, Holland, A & Oettle, S. 2020. The representation of women in the photographs of introductory human geography textbooks. Journal of Geography. 119(4):127-135. [ Links ]

Alayan, S & Al-Khalidi, N. 2010. Gender and agency in history, civics, and national education textbooks ofJordan and Palestine. Journal of Educational Media, Memory and Society. 2(1):78-96. [ Links ]

Anunobi, F. 2002. Women and development in Africa: from marginalization to gender inequality. African Social Science Review. 2(2):41-64. [ Links ]

Bentrovato, D. 2017. Learning to live together in Africa through history education: an analysis of school curricula and stakeholders' perspectives. Göttingen: V&R Unipress. [ Links ]

Bentrovato, D, Korostelina, K & Schulze, M. (eds.). 2016. History can bite: history education in divided and postwar societies. Göttingen: V&R Unipress. [ Links ]

Blumberg, RL. 2007. Gender bias in textbooks: a hidden obstacle on the road to gender equality in education. (A paper commissioned for the EFA Global Monitoring Report 2008, Education for all by 2015). UNESCO. [ Links ]

Bourdieu, P & Passeron, JC. 1990. Reproduction in education, society and culture. London: SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

Bryman, A. 2012. Social Research Methods. 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Chick, KA. 2006. Gender balance in K-12 American history textbooks. Social Studies Research and Practice. 1(3):284-290. [ Links ]

Chimbunde, P & Kgari-Masondo, MC. 2021. Decolonising curriculum change and implementation: voices from social studies Zimbabwean teachers. Yesterday & Today. (25)1-22. [ Links ]

Chiponda, A Fatsireni. 2014. An analysis of the portrayal of women in junior secondary school history textbooks in Malawi. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis. Durban: The University of KwaZulu-Natal. [ Links ]

Chiponda, A & Wassermann, J. 2011. Women in history textbooks - what message does this send to the youth? Yesterday & Today. (6)13-25. [ Links ]

Chiponda, A & Wassermann, J. 2015. An analysis of the visual portrayal ofwomen in junior secondary Malawian school history textbooks. Yesterday & Today. (14)208-237. [ Links ]

Creswell, JW. 2007. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among the five approaches. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

De Sousa Santos, B. 2007. Beyond abyssal thinking: from global lines to ecologies of knowledge. Eurozine. 33:45-89. [ Links ]

Dudu, W, Gonye, J, Mareva, R & Sibanda, J. 2008. The gender sensitivity of Zimbabwean secondary school textbooks. Southern African Review of Education. 14(3):73-88. [ Links ]

Gebriel, D. 2018. Rhodes Must Fall: Oxford and movements for change, in Decolonising the University, edited by GK Bhambra, D Gebriel & K Nisancioglu. London: Pluto Press. 19-36. [ Links ]

Geisler, G. 1987. Sisters under the skin: women and the Women's League in Zambia. The Journal of Modern African Studies. 25(1):43-66. [ Links ]

Gordon, DM. 2008. Rebellion or massacre? The UNIP-Lumpa conflict revisited, in One Zambia, many histories towards a history of post-colonial Zambia, edited byJB Gewald, M Hinfelaar & G Macola. Leiden: Brill.45-76. [ Links ]

Jaiyeola, EO & Aladegbola, I. 2020. Patriarchy and colonisation: the" brooder house" for gender inequality in Nigeria. Journal of Research on Women and Gender. 10:3-22. [ Links ]

Kabombwe, YM. 2019. Implementation of the competency-based curriculum in the teaching of history in selected secondary schools in Lusaka, Zambia. Unpublished M.Ed thesis. Lusaka: University of Zambia [ Links ]

Kabombwe, YM & Mulenga, IM. 2019. Implementation of the competency-based curriculum by teachers of history in selected secondary schools in Lusaka district, Zambia. Yesterday & Today. (22)19-41. [ Links ]

Lyon, T. 2002. Guerrilla Girls and Women in the Zimbabwean National Liberation Struggle in Women in African Colonial Histories, edited byJ Allman, S Geiger & N Musisi. Bloomington IN: Indiana University Press. [ Links ]

Maldonado-Torres, N. 2007. On the coloniality of being. Cultural Studies. 21(2-3):240-270. [ Links ]

Mboyonga, E. 2019. The role of ICTs in teaching social studies: Implications for 21st century teaching and learning pedagogies in Zambia. Paper presented on 29th November, 2019 at the Fall Season Fulbright Teaching Excellence and Achievement Conference. Washington DC. [ Links ]

Mburu, DNP & Nyaga, G. 2012. Effects of gender role portrayal in Kenyan primary schools, on pupils academic aspirations. Problems of Education in the 21st Century. 47:100-109. [ Links ]

Meghji, A. 2021. Decolonising is about adding, not cancelling, knowledge. University World News: Global Edition. 11 September. Available at https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=2021090713235631 Accessed on 20 November 2021. [ Links ]

Merriam, SB & Tisdell, EJ. 2015. Qualitative research: a guide to design and implementation. 4th ed. San Francisco, CA: Wiley. [ Links ]

Ministry of Education. 2013. Zambian education curriculum framework 2013. Lusaka: Curriculum Development Centre. [ Links ]

Ministry of Education (MOE). 1996. Educating our future: National Policy on Education. Lusaka: ZEPH. [ Links ]

Ministry of Education, Science, vocational training and early childhood education. 2013. Grade 10-12 history syllabus. Lusaka: Curriculum Development Centre. [ Links ]

Munga, E. 2016. The Lumpa Church: its socio-economic impact in Lundazi District in the eastern province of Zambia, 1955-1955. Unpublished M.A. History Thesis. Lusaka: The University of Zambia. [ Links ]

Musilekwa, S. 2019. An analysis of the development of social studies learners textbooks for junior secondary in Zambia. Unpublished M.Ed. thesis. Lusaka: The University of Zambia. [ Links ]

Mutekwe, E & Modiba, M. 2012. An evaluation of the gender sensitive nature of selected textbooks in the Zimbabwean secondary school curriculum. Anthropologist. 14(4):365-373. [ Links ]

Mwanza, C. 2017. Teacher involvement in curriculum development in Zambia: a role analysis of selected secondary school teachers in Lusaka district, Lusaka Province, Zambia. Unpublished M.Ed thesis. Lusaka: The University of Zambia. [ Links ]

Nasibi, MW. 2015. A critical appraisal of history taught in secondary schools in Kenya. International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development. 4(1):639-654. [ Links ]

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. 2013. Why decoloniality in the 21st century? The Thinker. 48:10-15. [ Links ]

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. 2019. Empire, decolonisation and challenges ofAfrican development. The Hormuud Lecture. Boston: African Studies Conference. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MyySH6T1Ong Accessed on December 2021. [ Links ]

Okoth, A; Ndalo, A & Mashwekwa, J. 2017. Achievers senior secondary history learner's book, 12. Lusaka: East Africa Educational Publishers Ltd. [ Links ]

Osleen, L. 2019. Why teaching history is important: but only when it is taught with a view towards the future. Age of Awareness. Available at https://medium.com/age-of-awareness/why-teaching-history-is-important-3a4c52c9908d Accessed on 9 September 2021. [ Links ]

Quijano, A. 2007. Coloniality and modernity/rationality. Cultural Studies. 21(2-3):168-178. [ Links ]

Roberts, MN. 2013. The king is a woman: shaping power in Luba royal arts. African Arts. 46(3):68-81. [ Links ]

Samanga, R. 2019. The Zambian women's history museum is returning to Africans what colonialism stole. Okay Africa. Available at https://www.okayafrica.com/samba-yonga-womens-history-museum-in-zambia-africa/ Accessed on 31January 2020. [ Links ]

Schocker, JB & Woyshner, C. 2013. Representing African American women in US history textbooks. The Social Studies. 104(1):23-31. [ Links ]

Schoeman, S. 2009. The representation of women in a sample of post-1994 South African school history textbooks. South African Journal of Education. 29:541-556. [ Links ]

Sharma, G. 2019. Museum of women: how Zambia inherited patriarchy from colonialism. Available at https://www.trtworld.com/magazine/museum-of-women-how-zambia-inherited-patriarchy-from-colonialism-29729 Accessed on 11 November 2021. [ Links ]

Sikanyiti, D & Sally, E. 2017. Excel and advance in history: learner's book, Grade 12. Lusaka: Grey Matters Ltd. [ Links ]

Spencer-Wood, SM. 2016. Feminist theorising of patriarchal colonialism, power dynamics, and social agency materialised in colonial institutions. International Journal of Historical Archaeology. 20(3):477-491. [ Links ]

Szórádová, E. 2015. Contexts and functions of music in the Orbis sensualium pictus textbook by John Amos Comenius. Paedagogica Historica International Journal of the History of Education. 51(5):535-559. [ Links ]

UNICEF. 2020. Gender equality: global annual results report 2019. New York: UNICEF. Available at https://www.unicef.org/media/71421/file/Global-annual-results-report-2019-gender-equality.pdf. Accessed on 10 August 2021. [ Links ]

Wills, L. 2016. The South African high school history curriculum and the politics of gendering decolonisation and decolonising gender. Yesterday & Today. (16):22-39. [ Links ]