Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Yesterday and Today

On-line version ISSN 2309-9003

Print version ISSN 2223-0386

Y&T n.26 Vanderbijlpark Dec. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2223-0386/2021/n26a4

ARTICLES

Fallism as Decoloniality: Towards a Decolonised School History Curriculum in Post-colonial-apartheid South Africa

Paul Maluleka

University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa paul.maluleka@wits.ac.za Orcid 0000-0003-3168-150X

ABSTRACT

The 2015/16 student protests in South Africa, dubbed #MustFall protests, signalled a historic moment in the country's post-colonial-apartheid history in which student-worker collaborations called for the decolonising of the university and its Eurocentric curriculum and, by extension, basic education and its Eurocentric curriculum too. Since then, there have emerged two dominant narratives of decolonisation in South Africa. The first is what I call a nativist delinking approach that recentres decolonial and Africa-centeredness discourses, ontologies, and epistemologies relatively separate from Euro-north and American-centric ones. The second is a broader, inclusive approach to decolonisation, which this study adopts. However, both these dominant narratives fail to counter much of the knowledge blindness informed by a false dichotomy advanced by positivist absolutism and constructive relativism that defines the sociology of education, including many of the calls for decolonisation. Thus, through a decolonial conceptual framework and Karl Maton's Epistemic-Pedagogic Device as a theoretical framework, fallism as decoloniality is adopted in this study to propose ways to transcend the Eurocentrism that characterises the current school history curriculum in South Africa, as well as the nativist and narrow provincialism of knowledge. Equally, an argument is made for the advancement of an inclusive decolonial project that is concerned with relations within knowledge and curriculum and their intrinsic structures.

Keywords: Fallism; Decoloniality; Decolonisation; School History; CAPS; Epistemic-Pedagogic Device; Curriculum knowledge; Fees Must Fall.

Introduction

For many years, South Africa's black1 youth have been engaged in protracted struggles for the decolonisation of their education system. The 2015/16 black student-led protests, dubbed #MustFall protests, intensified these struggles seeking to decolonise the contemporary South African education system. In this article, I propose an argument for the decolonisation of curriculum knowledge in the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) School History Curriculum (SHC) for Further Education and Training (FET) phase in post-colonial-apartheid South Africa through the adoption of an inclusive decoloniality that centres fallism. The article begins with a brief discussion of Maton's (2014) Epistemic-Pedagogic Device (EPD) and its usefulness in allowing me to employ and apply fallism to a basic education subject when, in the main, it is exclusively employed and applied in higher education settings and their academic disciplines. This is followed by a discussion of the decolonial conceptual framework adopted by centring fallism as decoloniality. The use of theories of the Global North (e.g., EPD) jointly with theories from the Global South (e.g., fallism) is deliberate because the decoloniality advanced in this article is an approach that is for knowledge pluralisation. It is what Hountondji (1997:17) terms endogenous knowledge - an approach to knowledge that "create[s] bridges, [and] recreate^] the unity of knowledge, or in simpler, deeper terms, the unity of the human being". Thirdly, a brief discussion on post-1994 SHCs and how they continue to be colonised is made. Fourthly, a discussion on forms of curriculum and knowledge is carried out. Lastly, I propose ways in which curriculum knowledge that characterises the CAPS SHC can be decolonised.

Karl Maton's epistemic-pedagogic device

Karl Maton introduced the EPD, drawing heavily from Bernstein's pedagogic device (PD). This is because Bernstein's PD is useful in understanding the mechanics behind relaying what he called the three key "message" systems, namely curriculum, pedagogy, and evaluation (Bernstein, 1975). Bernstein also argues that the PD comprised three different yet internally related fields of practice:

The production field

The production field is where new curriculums or specialised knowledge, discourses and ideas are continuously established, developed, and produced. This field is regulated by distributive rules that in turn regulate power relations between social groups. Thus, these distributive rules "help distinguish between two classes of knowledge: - the thinkable and the unthinkable, the esoteric and the mundane, the knowledge of the oriental other, and the otherness of knowledge" (Bernstein, 1996:28-29). In the post-colonial-apartheid South African context, the former is thought of, in Bernsteinian (1996, 1999) understanding of knowledge structures, as being part of the vertical discourse that is made of knowledge forms considered to be explicit, coherent, and organised. These are Euro-Western forms of knowledge that are characterised by ideas of the modernity/coloniality project. These forms of knowledge are conceptualised and represented as being formal, scholarly, or specialised. The latter are forms of knowledge thought of as being part of a horizontal discourse that is made ofknowledge forms that are vague, incoherent or muddled, and jumbled or disorganised (Bernstein, 1996, 1999). These are considered informal, non-scholarly or non-specialised forms of knowledge. Usually, these are marginalised African-centred knowledge forms.

The recontextualisation field

The recontextualisation field is a site where curriculum or specialised knowledge, discourses and ideas produced in the production field are selected and transferred to sites of reproduction, which are mainly, but not exclusively, the school. For Bernstein (2000), this process entails the principles of de-location (i.e., selecting a discourse or part of a discourse from the field of production, such as a university), and re-location (i.e., the placement of that part or whole discourse into a field of reproduction, such as the school). Moreover, Bernstein stresses that during the de-location and re-location process, the original discourse can undergo an ideological transformation.

This field is regulated by recontextualising rules which regulate the formation of specific pedagogic discourses (Ensor, 2004). Pedagogic discourse is "...the principle by which other discourses are appropriated and brought into a special relation with each other, for the purposes of their selective transmission and acquisition. Pedagogic discourse is a principle for the circulation and the reordering of discourses" (Bernstein, 1996:46-47). For instance, pedagogic discourses can speak to curriculum design decisions made by curriculum designers and policymakers relating to knowledge, pedagogy, and assessment. These decisions usually result in, for instance, the inclusion and exclusion of certain knowledge. A case in point is the continued inclusion of Euro-Western forms of knowledge in the SHC in post-colonial-apartheid South Africa at the expense of African-centred knowledge forms. Hence, for Bernstein (1975, 1996) these recontextualising rules are governed by two sets of rules (or logics), which are the instructional discourse (ID) and the regulative discourse (RD). The ID denotes what is usually referred to as content knowledge, and this may include facts, specialised texts or theories based on a subject discipline. The RD, on the other hand, concerns moral values, behaviour, orderliness, character, identity, and attitude. It is concerned with what pupils exhibit in, or what attitudes they are encouraged to bring into, the classroom.

The reproduction field

The reproduction field is a site where processes and decisions from both the production and recontextualisation fields find expression. In other words, the new curriculum or specialised knowledge, discourses and ideas produced in the production field are recontextualised in the recontextualisation field, and the other curriculum design imperatives advanced by curriculum designers and policymakers are implemented. This means the reproduction field is where teaching and learning, characterised by various dominant and favoured knowledge forms of the day, dominant pedagogics choices, and assessment practices, take place. Thus, this field is regulated by evaluative rules, which in turn "regulate the recognition, selection and recontextualisation of official knowledge. It is within this field of reproduction that educators employ their pedagogy to determine processes involving, for example, the selection of knowledge; sequencing of content; pacing of lessons" and the evaluation or assessment of their learners (Gerassi, 2016:17). Additionally, Gerassi (2016:17) notes that:

Bernstein acknowledges that learners, too, have the opportunity to further recontextualise the pedagogy used by the educator. They may, for instance, use their own processes of knowledge recognition or their own "evaluation criteria" to legitimise or challenge school knowledge. In this way, the pedagogic practice provides a means for initiating change in the power relations and mechanisms of control between educators and learners.

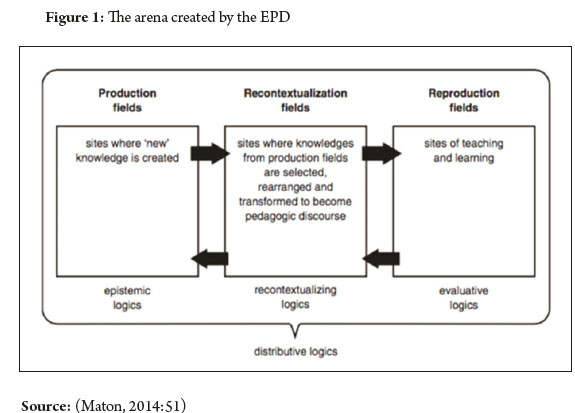

Maton (2014), drawing from PD, developed the EPD to argue that the fields of practice are not only interrelated but are dialectical and intersectional too. This means that EPD, for instance, does not view the conceptualisation, development, and production of new curriculums or specialised knowledge, discourses and ideas as only happening in the PD's production field. Rather, what EPD argues is that such new knowledge can also be conceptualised and produced in the reproduction field. In other words, new specialised knowledge, discourses, and ideas are not always or only produced in the production field, and it is only through specific pedagogic discourses embedded within the recontextualisation field that they can find expression in the reproduction field. What EPD argues is that such new knowledge can be produced in the reproduction field and thus can dialectically and intersectionally move from this field to the production field through specific pedagogic discourses embedded within the recontextualisation field. Figure 1 depicts processes embedded within the EPD (Maton, 2014:51):

In this article, drawing from both PD and EPD's interrelational, dialectical and intersectional posture, I focus on the reproduction field as a field in which the 2015/16 student movements and their protests are located. I argue, therefore, that the students were able to produce new specialised knowledge, discourses, and ideas, i.e., fallism, that in turn, have been recontextualised in the recontextualisation field and been (and continue to be) dialectically and intersectionally moved to the production field. From this logic, it is then possible to employ fallism and apply it to basic education, specifically SHC. This is because, from Bernstein's PD, whatever is produced in the production field (mainly but not exclusively universities) gets recontextualised by curriculum designers and policymakers for educators and schools to adopt and apply in the reproduction field. So, EPD stretches the PD by strongly arguing that this process is not only straightforward but both dialectical and intersectional too. Over and above this, it is important to note that the 2015/16 black student cohort and those who came before and after them had already been exposed to colonial education and its effects before entering higher institutions of learning. Hence, their struggles and articulations of the need for a decolonised university should be read to speak directly to the need for the decolonisation of the basic education system too. This is because their encounter with colonial education dates back to their first day of formalised education. Hence, I am of the view that it would be a futile exercise to even begin to view basic education and higher education and their operative logics in South Africa as operating relatively separate from each other.

Fallism as decoloniality

On 9 March 2015, black students at the University of Cape Town (UCT) under the banner of #RhodesMustFall drenched the bronze statue of racist Cecil John Rhodes, situated on the lower part of Sarah Baartman Hall steps overlooking the university's rugby fields, in human excrement, demanding its removal from their campus. They viewed it as a symbol of white supremacy thinking, white arrogance, and white fragility that has deep historical roots dating back to colonial-apartheid years, being further entrenched, protected, and promoted in the post-colonial-apartheid university and society, and as needing to be dismantled. These acts were followed by many protest actions by students and workers across all public university campuses under the banner of #FeesMustFall over exorbitant tuition and hostel fees. These protests initially started at the University of the Witwatersrand (WITS) on October 14, 2015.2 However, it should be noted that student protests over exorbitant tuition and hostel fees in post-colonial-apartheid South Africa did not start in 2015 at WITS. In fact, for many years, students from the so-called historically black universities (HBUs) across the country have been protesting over such issues with little to no media coverage. So, students from HBUs are the first fallists.3 However, they are not seen as the first fallists because coloniality and its power matrix continue to construct these students, who are predominately black, as non-beings.

What then is fallism? And can it be decoloniality? First, it should be noted that there is no single all-encompassing definition of what fallism is. This is because those of us who consider ourselves as fallists come to interpret, reconstruct, and represent fallism differently in our different sites of struggles, many of which are similar and intersectional. Therefore, fallism is a collective noun we use to describe student movements at universities in postcolonial-apartheid South Africa that use the "Must Fall" hashtag (Ahmed, 2019). For this article, I too understand fallism to mean "an attempt to make sense of the experiences of Black people in a white, liberal university [and school], through decolonial theories centred on [intersectionality,] Pan-Africanism, Black Consciousness, and Black radical feminism" (Ahmed, 2019:np). This attempt was inspired by (South) Africa's rich history of struggles for decolonisation and youth uprisings.

Therefore, fallism, as employed in this article, seeks epistemic justice by challenging the continued expansion of the Western knowledge canon in the SHC through what decolonial scholars call "coloniality" (Fataar & Subreenduth, 2015). Coloniality is a term used to understand how the colonised continue to be dehumanised even though formalised colonialism has ended. It is also used to explain the "darker side" or "underside" of modernity that is often hidden and should be unveiled or unmasked. This side of modernity exists as an embedded logic, and EPD's distributive logics allow us to unveil and unmask its enforced domination, suppression, and exploitation of the oriental other. Maldonado-Torres (2007:243) asserts that coloniality:

...survives colonialism. It is maintained alive in books, in the criteria for academic performance, in cultural patterns, in common sense, in the self-image of peoples, in aspirations of self, and so many other aspects of our modern experience. In a way, as modern subjects, we breathe coloniality all the time and every day.

It is also maintained in the school through its curriculum, especially the SHC, and the general operative logic of the school, i.e., learners' codes of conduct, schools' visions, mission statements, and so on. Therefore, coloniality reproduces itself in three dialectical yet interrelated domains that include: "coloniality of power", "coloniality of knowledge", and "coloniality of being" (Maldonado-Torres 2016).

Coloniality of power

Coloniality of power seeks to explain "the structures of power, control, and hegemony that have emerged during the modernist era, the era of colonialism, which stretches from the conquest of the Americas to the present".4 It tells a story of how the Global North articulates its power to characterise, label, classify, totalise, and organise the world according to its narrow perceptions of the world through the SHC and other avenues. It is imposed through control of the economy; control of authority; control of gender and sexuality; and control of knowledge and subjectivity (Mignolo, 2007). Hence, Taylor (2013:598) asserts that "coloniality of power thus entails not only physical oppression, political authoritarianism and economic exploitation but most fundamentally epistemological domination". Within the EPD, coloniality of power can be allocated as operating in the distributive logics.

Therefore, the type of fallism employed here seeks to challenge this coloniality of power and ultimately the epistemological domination by bringing into the distributive logics of EPD as many players as possible. For instance, instead of having a situation whereby only white, cisgender men are at the centre of controlling the epistemic logics in the production field; we open up to accommodate the colonised too but not for the sake of accommodating. With that, we should be allowed and supported to theorise our lived experiences from our theoretical traditions. In that way, a pluralised knowledge production enterprise can be realised.

Coloniality of knowledge

Coloniality ofknowledge explains the continued monopolisation of knowledge production. This results in the systematic and institutional exclusion of other forms of knowledge in the curriculum and its knowledge-building and structuring processes (Boughey & McKenna, 2021). In challenging this, the type of fallism advanced here proposes an additive-inclusive and intersectional approach to curriculum knowledge production and building that "recognises and values existing cannons of knowledge and its addition to established world knowledges" (Jansen, 2017:160). This means that in our attempt to decolonise curriculum knowledge, we should not provincialise, marginalise and exclude other forms of knowledge the same way the Western knowledge canon sought to do and continues to do.

Instead, what we should strive to do is create a knowledge environment within the EPD's distributive logics in which knowledge pluralisation and intersectionality are at the centre of the academic enterprise. In this way, we can, for instance, recentre and "reconceptualise research participants [oMakhulu, etc.] as not only information mines, but as co-creators of knowledge, [because] oMakhulu have for decades analysed their social world thus creating knowledge in the process. But, because they may not have used "academic" theories and concepts, this knowledge exists outside of the academy" (Maluleka & Ramoupi, in press 2021). Magoqwana speaks about the need to reposition and re-historise uMakhulu in the SHC "...as an institution of knowledge that transfers not only 'history' through iintsomi (folktales), but also as a body of indigenous knowledge that stores, transfers, and disseminates knowledge and values" (Magoqwana 2018:76).

Coloniality of being

Coloniality of being explains the Manichean allegoric mode of binaries that continue to be used to categorise people and their culture as either Christian/barbarian, good/evil, primitive/civilised, inferior/superior, rational/irrational, white/black, knowledge/myths, and developed/undeveloped (Maldonado-Torres, 2016). This categorisation happens across the EPD's distributive logics.

The type of fallism employed here seeks to contribute to the rehumanisation of the dehumanised in and through the SHC. These are colonised people that Fanon (1961) described as the wretched of the earth who live in the "zone of non-being" (Mignolo, 2007), which for De Sousa Santos (2014:10), in a different context, designates a zone as "between No Longer and the Not Yet". This is because coloniality continues to socially produce what journalist Nat Nakasa5 called "natives of nowhere", who are primitive, inferior, irrational, and black. These are colonised people who, through the systemic and institutional exclusion of their ways of knowing and being, are dislocated from their being, culture, and indigenous identities (Kumalo 2018). This has resulted in these colonised people being pariahs who are homeless, de-homed, unhomed and worldless (Madlingozi, 2018). However, in its process of rehumanising the dehumanised, the type of fallism employed here also seeks to create a new white person who is a "fully conscious", free from all biases and the weakening effects of the abyssal imperial attitudes (Fanon, 1961).

Post-1994 school History curriculums: CAPS

Since the dawn of democracy in 1994, the South African democratic state, in partnership with stakeholders, has initiated numerous constitutional and educational reforms in a bid to ukuhlambulula the SHC from its colonial-apartheid past with the hope of re-establishing seriti sa MaAfrika6(Maluleka & Ramoupi, in press 2021). Tisani conceptualises ukuhlambulula as a process of cleansing, which entails "cleansing - inside and outside, touching the seen and unseen, screening the conscious and unconscious. This includes healing of the body and making whole the inner person, because in African thinking 'there is an interconnectedness of all things' (Thabede, 2008:238)" (Tisani, 2018:18). Therefore, the process of ukuhlambulula was initiated because colonial-apartheid education and its distributive logics were Eurocentric, racist, homophobic, sexist, misogynistic, authoritarian, prescriptive, unchanging, context-blind, and discriminatory (Maluleka, 2018). For instance, the apartheid school curriculum was underpinned by ideals of Christian National Education (CNE), Afrikaner Nationalism, white supremacy, and pseudo-scientific racism. Hence, Article 15 of the CNE policy of 1948 stated that:

We believe that the calling and task of White South Africa [concerning] the native is to Christianise him and help him culturally and that this calling and task has already found its nearer focusing on the principles of trusteeship, no equality and segregation. We believe besides that any system of teaching and education of natives must be based on the same principle. [Following] these principles, we believe that the teaching and education of the native must be grounded in the life and worldview of the Whites most especially those of the Boer nation as senior White trustee of the native ... (cited in Msila, 2007:149)

Therefore, the 1990s were a period in South Africa that could be characterised as "a decolonising moment" for various reasons (Christie, 2020:201). The first reason was the first ukuhlambulula process that began with the adoption of the democratic constitution of 1996, the National Education Policy Act 1996, and the South African Schools Act 1996, which saw 18 racially differentiated departments of education collapsed and replaced with a single, centralised national department of education assisted by nine provincial departments of education.

The second ukuhlambulula process entailed the adoption of the Curriculum 2005 in 1997. This was an Outcomes-Based Education (OBE) strategy which focused on the main outcomes of the educational process. This curriculum "was presented as an attempt to alter in the short term the most glaring racist, sexist and outdated content inherited from the apartheid syllabi" (Jansen, 2001:43). It was one of "the most radical constructivist curriculum ever attempted anywhere in the world" (Taylor 2000, cited in Hugo 2005:22). Its evaluative logics on the EPD were learner-centred (something that both educators and learners were not accustomed to), as opposed to being teacher-centred, as was the case under colonial-apartheid. Its epistemic and recontextualisation logics were still very much dominated and controlled by government officials, academics, policymakers, curriculum developers and so on, who were still very much aligned with colonial-apartheid. Thus, OBE failed.

But OBE also failed in South Africa for many other reasons. For instance, Jansen, in a paper entitled "Curriculum reform in South Africa: A critical analysis of Outcomes-Based Education", gave an account consisting of "10 major reasons" as to why he thought then that OBE would fail. His main thesis was that OBE would fail "...because this policy is being driven in the first instance by political imperatives which have little to do with the realities of classroom life" (Jansen, 1998:323). So, OBE failed because it was "primarily a political response to apartheid schooling" ( Jansen, 1998:321). In other words, naive optimism prevailed, driven by very sincere attempts to sweep out the old and usher in the new as speedily and completely as possible" (Siebörger & Dean, n.d.:3). Moreover, OBE's market fundamentalism outlook and its obsession with demonstrable proficiency of specific skills, knowledge, or behaviour meant that it was near impossible to meaningfully foreground African-centred knowledge forms in its curriculum knowledge structures. This is the knowledge that was still considered, and continues to be by some (see: Horsthemke, 2004a, 2004b), as forming part of the horizontal discourse, i.e., knowledge considered to be vague, incoherent or muddled, and jumbled or disorganised.

Due to the challenges that were identified by Jansen and others as constraining OBE, the Revised National Curriculum Statement (RNCS) was introduced in 2002, which signalled the third ukuhlambulula process (Chisholm, 2005). The RNCS was sold as being "designed on the principles of social transformation, human rights, inclusivity, as well as environmental and social justice" (Naidoo, 2014:4). Hence, it was characterised by three different pathways that learners could access after the end of Grade 9. These pathways included the general pathway, which was offered by all schools and incorporates grades 10 to 12; the general vocational pathway, which was to be offered by colleges who would, in turn, prepare learners for work that involves vocational skills; and the trade, occupational and professional pathway, which was to be offered by mainly industry-based providers through leadership (DoBE, 2002). Even with these pathways, the RNCS too was confronted with challenges. For instance, like OBE, it continued to foreground a market fundamentalist outlook, which meant that learner-centred approaches continued to dominate its evaluative logics, even though there was little to no training for educators. Its epistemic and recontextualisation logics continued to be dominated and controlled by those aligned with colonial-apartheid even though there was some form of transformation7(inclusion of some individuals from the previously colonised groupings) taking place in both logics.

Moreover, the absence of a soundly communicated plan for the implementation of the RNCS and the support of educators (DoBE, 2009) meant that "many educators who were reliant on the prescriptions of the colonial-apartheid SHC [were] forced to develop their learning programmes and learning support materials, which was something they never did under colonial-apartheid rule because everything was provided to them. Many decided to go back to teaching from the colonial-apartheid script because that was what they had access to" (Maluleka & Ramoupi, 2021). Equally, the fact that educators were themselves "products" of the colonial-apartheid education system (i.e., slave, mission, the extension of university education and Bantu education) exacerbated the problem because they were given few if any opportunities for unlearning internalised colonial attitudes and ethnics and relearning attitudes and ethnics founded on democratic principles. This is indicative of the government's failure to adequately prepare educators, especially those moving into peri-urban and rural schools that did not have strong school and district leadership and thus were not helped in acclimatising to the "decolonising moment" and it's imperative, nor were they guided in developing resources (Maluleka & Ramoupi, 2021). Equally, Euro-Western forms of knowledge continued to enjoy much coverage in the curriculum at the expense of African-centred knowledge forms. For instance, the RNCS even CAPS continued to "...privilege 'masculinist' interpretations of the past which contribute not only to the general marginalisation of women [minority groups and indigenous peoples' experiences] as subjects of history but more importantly reinforces or ignores oppressive gendered [and othering] ideas" (Wills, 2016:24).

A fourth ukuhlambulula process was initiated to review the RNCS. This resulted in the CAPS being announced in 2010, and it is currently in use. According to the Department of Basic Education (DoBE) Minister, Mrs Angie Motshekga, CAPS is not a new curriculum but a revision of the RNCS (DoBE, 2011). The evaluative logics of CAPS attempt to strike a balance between teacher-centred and learner-centred approaches to teaching and learning. Within this logic, we see more and more young educators joining the teaching profession. These are young professionals who, one hopes, understand and appreciate the importance of democratising knowledge in the classroom. By this I mean the teaching of history from a perspective informed by a plurality of knowledge forms to "pursue a robust social science by triangulating a wide range of partial perspectives, which would yield 'stronger objectivity' than the 'God trick' of supposed objectification from a dis-interested universal perspective" (Haraway, 1988 as developed in Zipin, Fataar & Brennan, 2015:16). One also hopes that these young professionals are aware of school history being part of the horizontal knowledge structures within the vertical discourse (Young, 2008). I elaborate further on this point in the next section.

CAPS recontextualisation and epistemic logics are, however, not yet fully transformed despite 27 years of a democratic dispensation. This is telling of a coloniality/modernity project hellbent on preserving the status quo that is characterised by epistemicide, culturecide, and linguicide. For instance, Wills (2016) critiques CAPS at the level of both of these operative logics. She argues that despite CAPS making inroads in as far as attempting to include and re-historicise "women's experiences, and scholarship in women's history" (Wills, 2016:24); "as it stands if we are to pursue decolonisation of the curriculum at all, 'mentioning' women is not a radical enough move towards conceptualising women and representing gendered historical concepts in ways which do not re-inscribe a practice of epistemic erasure or the textual inscription of damaging stereotypes and ideologies" (Wills, 2016:24-25).

In an attempt to transcend this, at least at the level of recontextualisation and evaluative logics, the current South African government, through its DoBE, initiated what I see as its fifth ukuhlambulula process in its curriculum reform. This saw the appointment of a History Ministerial Task Team8 (HMTT) on 4June 2015 that was mandated to work within outlined terms of reference, which were officialised publicly in October 2015.9 These terms of reference were centred around the HMTT needing to conduct a "comparative case study on compulsory History in certain countries..."10 because the "Minister further made comments about the content of the history curriculum and the way history is being taught in our schools".11 The actual terms of reference that the HMTT had to work within include:

To advise on the feasibility of making History compulsory in the FET phase;

To advise on where History should be located in the curriculum (for example, should it be incorporated into Life Orientation or not);

To review the content and pedagogy of the History curriculum with a view to strengthening History in the curriculum; and

To investigate the implications (for teaching, classrooms, textbooks, etc.) of making History a compulsory subject.12

In its final report to the ministry of the DoBE, the HMTT made several suggestions that have profound implications for the distributive logics of CAPS. Firstly, the HMTT's interim suggestion was that CAPS needed to be strengthened. They rationalised this by arguing that they were ". against the exercise of wholesale changes or a complete overhaul of the CAPS syllabus and content at this present time. [They] felt that this was too soon, instead, the MTT focused on the exercise of using the CAPS syllabus as the basis of strengthening the content in the interim, hoping that a complete overhaul of the CAPS syllabus and content will be carried out by the DoBE in future. This will depend, among other issues, on whether history will be a compulsory, fundamental subject at FET phase."13

In terms of what could be read as a decolonising imperative, the HMTT suggested that:

... that Africa centeredness becomes a principle in revisiting the content, and in particular bringing both ancient history and pre-colonial African history into the FET curriculum. Ghana's History syllabus at Senior High School, 1-3, that is, Grades 10, 11 and 12 is instructive in this regard. This is critical to understanding the layered history of South Africa and the continent of Africa at a more developed conceptual level. We recognise that certain aspects of pre-colonial history are taught in the GET curriculum, however, this tends to be portrayed as a "happy story", appropriate to that level, but fails to provide the nuanced and complex history which should be taught at a higher level at the FETphase. A conscious move away from this superficial history would also provide a bridge between GET, FET history and history taught at universities. Problematic and controversial issues and themes in ancient history and pre-colonial history of Africa should not be avoided. For example, themes about class, social stratification, kings and commoners, the status of women and workers in ancient history and also in pre-colonial history must be included.14

The DoBE is yet to work at materially implementing some of these suggestions from the HMTT. There has, however, been some critique of the work of the HMTT, especially in academic spaces. For instance, Van Eeden and Warnich (2018:18) reflect, firstly, on "the History MTT's discussion of the status of, specifically, compulsory History in Africa and further afield, and to establish whether the MTT's report can in this regard serve as a reliable indicator for making any informed decision on whether History Education in South African schools should indeed be compulsory up to the Grade 12 level.". Secondly, they "... contest the quality of the research conducted by the [HMTT about] compulsory History in other countries, which in turn questions the reliability of the Report in its entirety" and blame this on the "lack of inclusivity of expertise in the [HMTT], especially experts in History education" (Van Eeden & Warnich 2018:38). And finally, given what they say, their "contestation on [the] quality [of] the first section of the [HMTT] report" (Van Eeden & Warnich 2018:38), Van Eeden and Warnich make recommendations to the DoBE as to what aspects they think were ignored by the HMTT in their research and reporting, and why these aspects should be considered for further research before recommendations by the HMTT can be implemented.

All of these developments highlight an embedded contestedness of the distributive logics of a curriculum like the SHC, especially in countries like South Africa, whose present is still characterised by divisions from its historic past.

Forms of curriculum and knowledge

Curriculum, as a concept, is deeply contested because conceptualisations and meanings are understood differently. Generally, the curriculum is understood to be within the following considerations:

the ontological level (that is, the nature or essence of curriculums in different historical moments and time), the level epistemological (that is, the theories of knowledge that underpinned curriculum studies at various times) and methodological level (that is, the theories of methods that focus on curriculum studies which concern the different approaches to learning, teaching, assessment, and others) (Du Preez 2017, as developed in Hlatshwayo, 2018:76).

Eisner (1985) suggests that we note other considerations in our quest to understand curriculum in its entirety. These include the explicit, implicit (hidden) and null curriculum. The explicit curriculum is what is provided to learners by teachers, and this usually includes prescribed textbooks, assessment activities and guidelines. It is thus located in the recontextualisation and reproduction field. The implicit curriculum speaks to the culture and values (i.e., ways of knowing and being) of those who are dominant or powerful in a society, which are taught to unsuspecting learners (Apple, 1971). This curriculum can also be seen as a site for what Young (2008) terms knowledge of the powerful, which speaks to who defines what counts as knowledge and has access to it. This curriculum should be seen as a site where coloniality most implicitly reproduces itself. It operates in the EPD's distributive logics. The null curriculum is what is left out in officialised curriculums - what is not taught to learners. African-centred knowledge forms form part of this curriculum. These are forms of knowledge that the 2015/16 cohort of students sought to recentre through their struggles located in the EPD's reproduction field.

Thus, all of these considerations suggested by Hlatshwayo et al are grounds for contestations, struggles for decolonisation (Le Grange 2016). I propose ways in which some of these aspects of the curriculum can be decolonised in the next section. I now turn my focus to different forms of knowledge.

Sociologists of education are of the view that knowledge is differentiated (Young 2008) into two types, namely the formal, scholarly, or specialised knowledge (i.e., school knowledge that is part of the vertical discourse) and the informal, non-scholarly, or non-specialised knowledge (i.e., non-school knowledge that is part of the horizontal discourse). School knowledge is curriculum knowledge or subject-matter knowledge that is officialised and goes through the PD. It is the knowledge that Young (2008) termed as powerful knowledge and Bourdieu (2011) termed as symbolic capital. This knowledge is also disciplinary knowledge, which for Young is "context-independent" because it is developed for informed generalisations about the natural and social world - what Bernstein (2000) sees as being part of hierarchical knowledge structures because academic disciplines such as physics located in this knowledge structure "tend to have a vertical knowledge structure in which scholars are cumulatively building knowledge on "testable" and "objective" uniformities that comply with general propositions and agreement in the field, on how knowledge is produced, and who counts as a legitimate knower in such a field" (Hlatshwayo, 2018:43). This community of practice usually universalises any understanding of knowledge, which in turn becomes a breeding ground for coloniality and Eurocentrism. This is because any understanding of knowledge that is not legitimated within this community of practice and their fields of practice is rejected, the case in point being African-centred knowledge forms. In contrast, academic disciplines within the humanities and social sciences, such as school history, form part of Bernstein's horizontal knowledge structures within vertical discourse. Knowledge in these fields is underpinned by a series of specialised languages of legitimation, which for (Maton, 2013:23) refers to the "claims made by actors for carving out and maintaining spaces within social fields of practice". For Hlatshwayo (2018:44), knowledge governed by horizontal knowledge structures "tend to be segmented, with different scholars not cumulatively building knowledge atop one another, but rather introducing new theories, concepts, even competing with one another and replacing each other. This means that horizontal knowledge structures do not generally attempt to create general propositions and agree upon theoretical and conceptual tools that 'conform' to 'objective' or 'testable' realities." An example of such are the varied debates on meanings attached to the decolonisation of the SHC to which this very article seeks to contribute. Beyond these knowledge structures, Bernstein has also introduced us to discursive and ideational formations of knowledge that assist us to grapple with his concepts of classification and framing, which provide one with a special language for the description of pedagogic discourse (Hoadley 2005).

Bernstein (1975:88) defines classification as "the degree of boundary maintenance between content", i.e., the strength or weakness of the boundaries which exist between different categories such as academic subjects, agents and spaces agencies, contexts, discourses, or disciplines. This means that classification can be relatively stronger (C+) or weaker (C-). In other words, C+ refers to the structure of a curriculum extremely differentiated and separated into specific academic disciplines and subjects (Gerassi 2016). This then enables academic subjects and disciplines to differentiate themselves amongst each other. Thus, any form ofmultidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity, or merged disciplinarity are discouraged in this instance. Moreover, C+ maintains that a boundary exists between school knowledge that is formal, scholarly, and specialised and non-school knowledge that is informal, non-scholarly and non-specialised. Therefore, C- does the opposite of C+ because it collapses the boundaries in curriculum structures that differentiate and separate specific academic disciplines and subjects. Thus, C- encourages any form of multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity, or merged disciplinarity between academic subjects and disciplines. It also creates room in the curriculum structure for non-school knowledge to be integrated with formal, specialised, and scholarly curriculum knowledge. These have profound implications for how we think of a decolonised SHC and how can be achieved. For instance, C- collapses the power relations that exist between educators and their learners when C+ is in place, i.e., the integrations of specialised curriculum knowledge and "everyday" knowledge "challenges the distinction between educators and learners and, by way of extension, their relations of power (Bernstein 2000)" (Gerassi, 2016:13). In other words, where C+ "refers to clearly defined pedagogic identities between educator and learner (and, through systems of prefecture, between learner and learner)", C- "refers to poorly defined or blurred pedagogical identities" (Gerassi, 2016:13). Moreover, the fact that under C- learners are considered active participants in knowledge production, as opposed to tabula rasas under C+, challenges the pedagogical distinction between educators and learners and, by extension, specialised curriculum knowledge and non-school "everyday" knowledge.

Framing, on the other hand, refers to "...the degree of control teacher and pupil possess over the selection, organisation, pacing and timing of the knowledge transmitted and received in the pedagogical relationship" (Bernstein 1977:89), i.e., the control of meaning in pedagogic communication (Maton 2010), because it "...regulates the form of its legitimate message" (Bernstein 1999:100) and addresses "the strength of the boundary between what may be transmitted and what may not be transmitted" (Bernstein 1975:89). Hlatshwayo (2018:41-42) expl ains framing as ".concerned with the control over knowledge construction and its pedagogic transmission, through selection (what counts as legitimate knowledge), sequencing (how this knowledge is arranged in the curriculum), pacing (the expected or anticipated rate of acquisition for students in the curriculum), and evaluation (assessment and criteria of ensuring that this knowledge is received and reproduced)". Therefore, like classification, framing can be relatively stronger (F+) or weaker (F-) too (Hlatshwayo, 2018:41-42).

F+ means that educators have full control over pedagogic processes and can determine what is legitimate or valid knowledge (C+) and what is not (C-), i.e., what knowledge can be deemed specialised or "everyday". This makes F+ a teacher-centred approach to teaching and learning because educators have more control over the selection, pacing, sequencing, and evaluation of the curriculum knowledge (C+/F+). F- is the opposite of F+. Under F-, the approach to teaching and learning is learner-centred as opposed to being teacher-centred. Thus, learners, instead of educators, have more control over the selection, pacing, sequencing, and evaluation of the curriculum and can determine, to some extent, which knowledge to focus on and which to ignore (C-/F-).

Therefore, Bernstein's understanding of different forms of knowledge is significant to any project that seeks to decolonise curriculum knowledge.

Conclusion: Towards a decolonised and inclusive school history curriculum

There is still much to be done when it comes to the decolonisation of SHC in South Africa (Godsell, 2019). Therefore, with this article I have attempted to contribute to this project by suggesting ways in which decolonisation of the SHC can be approached. This I did by firstly suggesting a decolonial conceptual framework and Karl Maton's Epistemic-Pedagogic Device as a theoretical framework that, in turn, enabled me to employ fallism as decoloniality. Through that, I was able to review why post-1994 SHCs continue to fail when it comes to decolonisation. Thirdly, I was able to review forms of curriculum and knowledge and then suggest ways in which decolonisation can be prioritised in the relations within knowledge and curriculum and their intrinsic structures (Lilliedahl, 2015).

With this, I argue that a mere replacing of Euro-Western knowledge with African knowledge forms does not constitute decolonising. In fact, what it constitutes is yet another marginalising act that results in other forms of knowledge being excluded - knowledge forms that can enrich the academic enterprise we are trying to create. Thirdly, to truly begin attempting to decolonise the SHC, we need to move beyond the rhetoric, metaphoric, and romanticisation of decolonisation. Therefore, what fallism as decoloniality offers to any decolonial project that seeks to decolonise the SHC is a space that values and allows for the emergence of knowledge pluralisation. This, in turn, compels all stakeholders involved in the making and implementation of what could be a decolonised SHC to know, understand, and create from different forms of knowledge and curriculum an SHC that allows educators and learners to engage with knowledge in ways that are open and inclusive. This means that when it comes to the classification (+/-) and the structuring ofknowledge in the curriculum in any of the distributive logics offered by EPD, there needs to be an integration of what is usually considered everyday knowledge into the curriculum, which will, in turn, allow for multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity, or merged disciplinarity with other disciplines and other forms of knowledge. By this, I do not mean that decolonial knowledge or African-centred knowledge is everyday knowledge and therefore illogical, disorganised, etc. And yes, there is knowledge that is everyday, illogical, disorganised, and does not belong in any school curriculum. Equally, not all knowledge can be included in the school curriculum.

However, what I mean by this is that any form of decolonial knowledge or African-centred knowledge forms that would be integrated into the school curriculum should also be subjected to disciplinarity skills that any knowledge incorporated into a school curriculum would undergo. In other words, when learners and educators engage with decolonial knowledge or African-centred knowledge forms, they should do so in ways that promote reading, writing, and thinking like a historian (see Wineburg, 1999; Seixas, 2017). Therefore, the process of integration of decolonial knowledge or African-centred knowledge forms into the curriculum will in turn elevate the status of that very same knowledge, especially knowledge constructed by oMakhulu that is often acquired outside of the classroom. This will, in turn, dismantle, collapse, and undermine the privileged status that Euro-Western knowledge forms currently enjoy and create a situation whereby all centres or forms of knowledge are seen and treated equally. Thus, engaging them will be from that basis.

This has implications for pedagogy and how it comes to be framed (+/-). One thing about fallism is that it advanced a pedagogy approach that enabled and negotiated for different kinds of knowers to be legitimated (Hlatshwayo, 2018). Therefore, in our thinking of how we integrate decolonial knowledge or African-centred knowledge forms in a decolonised curriculum, we also need to think about the pedagogies, as well as assessments that will need to accompany this. Godsell (2019) offers an account of how poetry can be employed as a decolonising pedagogy in a history curriculum. Many such studies looking into pedagogy and assessment are imminent.

Acknowledgements:

The financial assistance of the National Institute for the Humanities and Social Sciences (NIHSS), in collaboration with the South African Humanities Deans Association (SAHUDA) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the NIHSS and SAHUDA

References

Ahmed, AK 2019. On black pain/black liberation and the rise of fallism. Available at https://blog.apaonline.org/2019/03/19/on-black-pain-black-liberation-and-the-rise-of-fallism/. Accessed on 15 August 2021. [ Links ]

Apple, MW 1971. The hidden curriculum and the nature of conflict. Interchange, 2(4):27-40. [ Links ]

Bernstein, B 1975. Class and pedagogies: Visible and invisible. Educational Studies, 1(1):23-41. [ Links ]

Bernstein, B 1996. The structuring of the pedagogical discourse: class, codes and control. Petropolis: Voices, 3719-3739. [ Links ]

Bernstein, B 1999. Vertical and horizontal discourse: An essay. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 20(2):157-173. [ Links ]

Bernstein, B 2000. Pedagogy, symbolic control, and identity: Theory, research, critique. London and Washington, DC: Rowman & Littlefield. [ Links ]

Boughey, C & McKenna, S 2021. Understanding higher education: Alternative perspectives. Cape Town: African Minds. [ Links ]

Bourdieu, P 2011. The forms of capital. Cultural Theory: An Anthology, 1:81-93. [ Links ]

Chisholm, L 2005. The making of South Africa's National Curriculum Statement. Curriculum Studies, 37(2):193-208. [ Links ]

Christie, P. 2020. Decolonising Schools in South Africa: The Impossible Dream? London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education, RSA 2002. Revised National Curriculum Statement. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education, RSA 2009. Report of the task team for the review of the implementation of the National Curriculum Statement. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education, RSA 2011. Curriculum and assessment policy statement, grades 10-12: History. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

De Sousa Santos, B 2014. Epistemologies of the South: Justice against epistemicide. Boulder: Paradigm Publishers. [ Links ]

Eisner, E 1985. Five basic orientations to the curriculum. In the educational imagination: on the design and evaluation of school programs. New York: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Ensor, P 2004. Legitimating school knowledge: The pedagogic device and the remaking of the South African school-leaving certificate 1994-2004. In: Third Basil Bernstein Symposium, University of Cambridge, July 2004. [ Links ]

Fanon, F 1961. The wretched of the earth. London: Penguin Books. [ Links ]

Fataar, A & Subreenduth, S 2015. The search for ecologies of knowledge in the encounter with African epistemicide in South African education. South African Journal of Higher Education, 29(2):106-121. [ Links ]

Gerassi, J 2016. Exploring the impact of the Flipped Learning Model (FLM) on educators' teaching practices at a private school in Johannesburg. Master's dissertation. Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand. Available at http://hdl.handle.net/10539/22622. Accessed on 5 August 2021. [ Links ]

Godsell, S 2019. Poetry as method in the History classroom: Decolonising possibilities. Yesterday&Today, 21:1-28. [ Links ]

Hlatshwayo, MN 2018. I want them to be confident, to build an argument: An exploration of the structure of knowledge and knowers in Political Studies. Doctoral thesis. Grahamstown: Rhodes University. Available at http://hdl.handle.net/10962/92392. Accessed on 5 August 2021. [ Links ]

Hoadley, U 2005. Analysing pedagogy: the problem of framing. University of Cape Town & Human Sciences Research Council. [ Links ]

Horsthemke, K 2004a. Knowledge, education and the limits of Africanisation. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 38(4)571-587. [ Links ]

Horsthemke, K 2004b. "Indigenous knowledge": Conceptions and misconceptions. Journal of Education, 32:31-48. [ Links ]

Hountondji, PJ 1997. Endogenous knowledge: Research trails. Dakar: CODESRIA. [ Links ]

Hugo, W 2005. New conservative or new radical: The case of Johan Muller. Journal of Education, 36:19-36. [ Links ]

Jansen, J 1998. Curriculum reform in South Africa: a critical analysis of outcomes-based education. Cambridge Journal of Education, 28(3):321-331. [ Links ]

Jansen, J 2001. Image-ining teachers: policy images and teacher identity in South African classrooms. South African Journal of Education, 21(4):242-246. [ Links ]

Jansen, J 2017. As by fire: The end of the South African university. Cape Town: Tafelberg. [ Links ]

Kumalo, SH 2018. Explicating abjection-Historically white universities creating natives of nowhere? Critical Studies in Teaching and Learning, 6(1):1-17. [ Links ]

Le Grange, L 2016. Decolonising the university curriculum. South African Journal for Higher Education, 30(2):1-12. [ Links ]

Lilliedahl, J 2015. The recontextualisation of knowledge: Towards a social realist approach to curriculum and didactics. Nordic Journal of Studies in Education Policy, 1:40-47. [ Links ]

Madlingozi, T 2018. Mayibuye iAfrika?: Disjunctive inclusions and black strivings for constitution and belonging in South Africa. Doctoral thesis. London: University of London. Available at http://vufind.lib.bbk.ac.uk/vufind/Record/589681. Accessed on 5 August 2021. [ Links ]

Magoqwana, B 2018. Repositioning uMakhulu as an institution of knowledge: Beyond "biologism" towards uMakhulu as the body of indigenous knowledge. In: J Bam, L Ntsebeza & A Zinn (eds.). Whose history counts? Decolonising African pre-colonial historiography (pp. 75-90). Cape Town: AFRICA Sun MeDIA. [ Links ]

Maluleka, P 2018. The construction, interpretation, and presentation of King Shaka: A case study of four in-service history educators in four Gauteng schools. Master's thesis. Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand. Available at https://hdl.handle.net/10539/26947. Accessed on 5 August 2021. [ Links ]

Maluleka, P & Ramoupi, NLL (in press, 2021). Towards a decolonized school history curriculum in post-apartheid South Africa through enacting legitimation code theory. In NM Hlatshwayo, H Adendorff, M Blackie, A Fataar & P Maluleka (eds.). Decolonising education and curriculum knowledge building in the university. Routledge. [ Links ]

Maldonado-Torres, N 2007. On the coloniality of being: Contributions to the development of a concept. Cultural Studies, 21(2-3):240-270. [ Links ]

Maldonado-Torres, N 2016. Outline of ten theses on coloniality and decoloniality. Frantz Fanon Foundation. [ Links ]

Maton, K 2010. Canons and progress in the arts and humanities: Knowers and gazes. Social realism, knowledge, and the sociology of education: Coalitions of the mind, 154-178. [ Links ]

Maton, K 2013. Making semantic waves: A key to cumulative knowledge-building. Linguistics and Education, 24(1):8-22. [ Links ]

Maton, K 2014. Knowledge and knowers: Towards a realist sociology of education. London and New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Mignolo, WD 2007. Introduction: Coloniality of power and de-colonial thinking. Cultural Studies, 21(2-3):155-167. [ Links ]

Msila, V 2007. From apartheid education to the Revised National Curriculum Statement: Pedagogy for identity formation and nation building in South Africa. Nordic Journal of African Studies, 16(2):146-160. [ Links ]

Muvangua, N & Cornell, D (eds.) 2012. uBuntu and the law: African ideals and postapartheid jurisprudence. New York: Fordham University Press. [ Links ]

Naidoo, A 2014 An analysis of the depiction of "big men" in apartheid and post-apartheid school history textbooks. Master's thesis. Durban: University of KwaZulu-Natal. Available at http://hdl.handle.net/10413/12634. Accessed on 1 August 2021. [ Links ]

Seixas, P 2017. A model of historical thinking. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 49(6):593-605. [ Links ]

Siebörger, R & Dean, J (n.d.). Values in a changing curriculum. University of Cape Town, Leeds Metropolitan University. [ Links ]

Taylor, L 2013. Decolonizing citizenship: Reflections on the coloniality of power in Argentina. Citizenship Studies, 17(5):596-610. [ Links ]

Tisani, NC 2018. Of definitions and naming: "I am the earth itself. God made me a chief on the very first day of creation". In J Bam, L Ntsebeza & A Zinn (eds.). Whose history counts? Decolonising African pre-colonial historiography (pp. 15-34). Cape Town: AFRICAN SUN MeDIA. [ Links ]

Van Eeden, ES & Warnich, P 2018. Reflecting the 2018 History Ministerial Task Team Report on compulsory History in South Africa. Yesterday&Today, 20:18-45. [ Links ]

Wills, L 2016. The South African high school History curriculum and the politics of gendering decolonisation and decolonising gender. Yesterday&Today, 16:22-39. [ Links ]

Wineburg, S 1999. Historical thinking and other unnatural acts. The Phi Delta Kappan, 80(7):488-499. [ Links ]

Young, M 2008. Bringing knowledge back in: From social construction to social realism in the sociology of education. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Zipin, L, Fataar, A & Brennan, M 2015. Can social realism do social justice? Debating the warrants for curriculum knowledge selection. Education as Change, 19(2):9-36. [ Links ]

1 Black, in this article, is used in a similar way to the Black Consciousness understanding of blackness to refer to all those who were oppressed under colonial-apartheid.

2 I was among the students who protested in 2015/16 against the exorbitant tuition and hostel fees imposed by the University of the Witwatersrand.

3 Fallist is a term that those of us who were part of the #MustFall protests use to describe each other and ourselves.

4 S Martinot, "The coloniality ofpower: Notes toward decolonization", accessed on 8 August 2021, from: https://www.globaljusticecenter.org/papers/coloniality-power-notes-toward-de-colonization

5 Nathaniel Ndazana Nakasa (1937-1965), better known as Nat Nakasa, was a South African journalist who worked during apartheid.

6 Loosely translated, this means the restoration of the dignity of Africans. Seriti literally means "a shadow" and is also more than an individuals existential quest for appearance. It is a "life force by which a community ofpersons are connected to each other" (Muvangua & Cornell, 2012, p. 529).

7 Transformation is understood in this instance to refer to the inclusion of those previously excluded from certain spaces.

8 Republic of South Africa (RSA), Department of Basic Education (DoBE), "Executive summary of the History Ministerial Task Team", ca January 2018.

9 RSA, DoBE, National Education Policy Act (Act no 27 of 1996), Establishment ofthe History Ministerial Task Team. Government Gazette (GG), Notice no 926, 9 October 2015.

10 RSA, DoBE, "Executive summary ofthe History Ministerial Task Team", ca January 2018, p. 9.

11 RSA, DoBE, "Executive summary ofthe History Ministerial Task Team", ca January 2018, p. 8.

12 RSA, DoBE, "Executive summary ofthe History Ministerial Task Team", ca January 2018, p. 8.

13 RSA, DoBE, "Executive summary ofthe History Ministerial Task Team", ca January 2018, p. 84.

14 RSA, DoBE, "Executive summary ofthe History Ministerial Task Team", ca January 2018, p. 132.