Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Yesterday and Today

On-line version ISSN 2309-9003

Print version ISSN 2223-0386

Y&T n.26 Vanderbijlpark Dec. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2223-0386/2021/n26a3

ARTICLES

People, space and time strategy: Teaching History through image analysis at a rural secondary school in Limpopo Province

Mahunele Thotse

University of Limpopo, Polokwane, South Africa Mahunele.thotse@ul.ac.za Orcid: 0000-0002-7015-2857

ABSTRACT

Efficient teaching approaches are critical to promote a positive attitude among learners of History at secondary schools. Learners' behaviour during History lessons and attitude towards the subject can be affected by a number of factors, including teaching methods, teaching styles, teacher's commitment and work ethic, etc. The study was conducted to examine the effect of using images in relation to the behaviour and attitude of learners towards the subject History. The study applies analytical research involving learners from a convenient group of schools around Mankweng in the use of the People, Space and Time (PST) image analysis strategy as a teaching strategy to affect the behaviour of learners towards the subject History. It uses image analysis to determine the effect of PST on the voluntary participation of learners in the History classroom. The results show that with careful organisation of visuals and crafting of questions, the PST method had a significant positive effect on learners' behaviour and attitude towards the subject. It was also observed that an increased number of learners responded comfortably to PST during class discussions. Teacher mentors have also shown interest in this strategy as learners seemed lively in class, with disinterest turning into interest as learner participation increased. The study concluded that an expert analysis of images is a key resource in the teaching of History.

Keywords: Image; Strategy; Analysis, Participation; Observation.

Introduction

Historical pictures or images play a critical role in the teaching of History in schools. Learners are not always enthusiastic about studying a past they cannot even imagine, so to bring the subject closer to reality and capture the learners' attention, it is important to make use of pictures. History teaching and learning has to be an exercise of engagement between instructor and learners, among learners, or between learners and the material studied, and pictures of the studied past will always come in handy. Further, History is about people who acted in a particular space and time in the past. Hence, it becomes even more relevant to apply the People, Space and Time (PST) image analysis strategy in the analysis of images that should explain that past. Participation during class discussions and overall learner engagement during History lessons at a few rural schools in Limpopo has been a worrying factor among History teachers. Learners are either shy or choose not to participate in class, including not asking questions, raising their hands or making comments unless requested by the instructor (Rocca, 2010). Reports indicate that only a handful oflearners participate during lesson discussions, with interactions made by only a small group of learners. A noted observation has been that larger classes in rural schools seem to provide more opportunity for anonymity and less opportunity to participate in discussions.

Background to the study

Apart from the concerns of History teachers, reports of the 2017 Postgraduate Certificate in Education (PGCE) show that student teachers at one teacher training institution in Limpopo, upon returning from teaching practice observations at schools, were generally concerned about the state of History teaching in general, and at the schools where they were deployed in particular. Student teachers were seriously concerned about teachers using the age-old traditional methods of History teaching, in particular the lecturing method. I shudder to imagine what the situation is now with even more pressure brought about by the impact of Covid-19.

Apparently, teachers were under pressure to complete the curricula and syllabi as prescribed in the History National Curriculum Statement (NCS) Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS). The CAPS document prescribes 35 teaching weeks for Future Education Training (FET) for Grade 10 and Grade 11, with an average of six weeks per topic plus assessment activities. There are six topics each for Grade 10 and Grade 12 and five topics for Grade 11. The six-week prescription per History topic excludes topic 1 in Grade 10 and topic 4 in Grade 11, which are allocated 3 and 10 weeks respectively. The reason for this is that these topics are too small and too large respectively, which also explains why the Grade 11 topics are five weeks instead of six (CAPS 2011).

The student teachers further observed that in response to the lecture method, learners were often passive and disinterested participants in class discussions (Bonwell & Eison, 1991; Brookfield & Preskill 2012), and in most sessions, answers were heavily reliant on the History teacher. Against the observed picture, the student teachers recommended that it might be better if some of the strategies forming part of the History Method modules were introduced to the History teachers in the affected schools. To achieve this, it was proposed that such teachers be coerced to sit in as mentors during the Teaching Practice sessions of either the final-year students doing the Bachelor of Education in Senior Phase and Further Education and Training (BEd SP & FET) programme or the PGCE programme. This would help them observe how a range of strategies can be used in the teaching and learning of the subject while learners are taught to become lively and engaged.

One way of dealing with the problem was to adopt the PST strategy of image analysis. The teacher trainees were grappling with methodology at the time, and it was perceived using images as resources in their History classes would have the potential to invigorate interaction not only between the teacher and the learners but also among the learners. This would support historical understanding and thinking, which would in turn support deliberation in the History classroom. The PST was then mooted as the technique and strategy to be adopted for use at some of these schools during the coming teaching practice sessions, with particular focus on the analysis of images during History teaching.

This study considered the use of the PST as a strategy that teachers can apply in the analysis of images when teaching History to encourage learner participation and understanding of the historical material.

Observations were conducted during History lessons while using a historical image to determine whether the treatment of photo images would lend into a different learner attitude and behaviour in terms of participation (be it positive or negative), which should also affect their confidence.

Critical social theory was used to understand the causes of poor performance in History teaching and learning as well as the schools' contextual factors that negatively impacted the teaching and learning of History in particular and in the school in general.

Literature review

The use historical sources such as pictures and other forms of art in school classrooms has been a subject of ongoing research. Sundar (2020) believes that as History learners, like any other learners, process information through both visual and auditory memory, presenting historical information in these formats could maximise their capacity to receive and process new information. According to O'Connor (1987:1), History teachers are expected to be more concerned with teaching learners how to learn from the study of the past, so one of the alternative ways of teaching should be to integrate more image analysis into their History lessons/classes, but not to the exclusion of reading or at the expense of traditional approaches.

This approach of engaging in an analysis requires that a teacher takes considerably more time to prepare for an image-oriented lesson, but when carefully integrated into the lesson and properly handled by the sensitive History teacher, lessons based on image analysis can improve the effectiveness of History teaching (Armstrong & Boud, 1983:92; Dancer & Kamvounias, 2005).

Participation in discussion leads to learning, including providing learners with opportunities to develop and practice essential skills such as organising concepts, formulating arguments, evaluating evidence and responding to ideas thoughtfully and critically (Davis, 2009). It further allows learners to experience a realistic context (Liang & Wang, 2004) and master the language and thinking of a discipline (Krupnick, 1985). The strategy entails engaging learners in the analysis of images.

McCarthy and Anderson (2000:279) found that students who participated in collaborative and analysis exercises did better on subsequent standard evaluations than their traditionally instructed peers.

In a lecture, students passively absorb pre-processed information and then regurgitate it in response to questions. There is a need to effect significant change in the passive nature of the History learning experience, which perpetuates learning at the surface (passive) level rather than the deep (active) level. Marton and Saljo (1976) agree that the lecture format will likely continue to be important in the learning process. This only increases the need for balancing passive with active learning.

Bonwell and Eison (1991) note that active learning strategies and techniques help create a more stimulating and enjoyable classroom environment for learners. Teachers must cover large quantities of information/syllabi in a limited period, yet they have an obligation to nurture learners' intellectual skills.

Objectives

• To examine the impact of the PST image analysis strategy on the attitudes and perceptions of learners towards History lessons.

• To examine the influence of the PST image analysis strategy on classroom discussion as an active learning strategy.

Rationale

The quality of participation in History class debates and discussions is affected by a number of factors including teaching strategies, effectiveness of teaching resources, etc. Voluntary participation by History learners in class discussion has often meant that learners understood the material studied and were confident in their critical thinking and argumentation skills. The study of the PST strategy may contribute towards learners of History being inculcated with a positive attitude towards the subject. The number of schools offering History and the number learners taking the subject have been dwindling over the years. Effective strategies and the improved quality of teaching the subject through the deployment of PST (among other strategies) may go a long way in instilling positive perceptions about History as a school subject. Despite the limitations of the research period due to Covid-19, positive signs were emerging that this might be one of the vehicles teachers could consider accommodating in the teaching of History, at least at these schools.

History teaching through image analysis

Teachers must show learners how to engage their critical faculties when a picture is displayed. This study is aimed at analysing a photo as a historical document. In doing so, two faculties in the analysis of an image were considered: (1) a general analysis of content, production, and reception; and (2) the study of the photo as a representation of history, as evidence for social and cultural history, as evidence for historical fact, or as evidence for the history of photography. Strategies for the classroom were also considered.

Within the context of an open and democratic society, History teachers have a broader responsibility to their learners than simply relating the events of the past by way of lecturing or simple story-telling. They must also provide learners with the skills of critical evaluation necessary to perform as responsible citizens, i.e., learners need to learn skills of critical evaluation (CAPS 2011:8) for the viewing of images (O'Connor 1987:3). Learners need to understand how the development of an image is an expression of technological limitations and media conventions (this is more relevant to TV and film).

This approach of engaging in analysis requires that a teacher take considerably more time to prepare for an image-oriented lesson, but when carefully integrated into the lesson and properly handled by the sensitive History teacher, lessons based on image analysis can improve the effectiveness of History teaching (Armstrong & Boud, 1983; Dancer & Kamvounias, 2005).

Discussions based on the group experience of a class viewing and analysis of a photo may be more productive than discussions of homework reading assignments, and poor readers and otherwise hard-to-motivate learners may find it easier to participate. If teachers were to devote some effort to taking a more active analytical approach to photo images, where applicable, this media would better serve the History classroom. Almost every course/theme in the History curriculum lends itself to at least some dimension of relevant image analysis. In addition to helping communicate subtle aspects of the historical subject matter, the structuring of a critical analysis of visual material within the context of traditional historical methodology helps teach learners the basic elements of historical thinking.

To achieve the stated aims of History teaching in schools through, among other things, participative discussion as a form of active learning, image analysis was adopted as an approach, and PST was the chosen strategy to execute that.

People, Space and Time strategy

Against the observed contextual situations in the schools, a decision was taken to adopt the PST strategy of image analysis espoused by Drake and Nelson (2005) as a methodology to invigorate interaction not only between the teacher and learners, but among the learners. This method was chosen for its potential to support understanding and critical thinking through deliberation in the classroom. Using this strategy, the aim was not for the facilitator to use the photo in a lecture where the teacher simply displays the photo and starts explaining its meaning to the learners. Even if the teacher were an expert on image analysis and could clearly analyse its key aspects, the lecture method would not provide for the planned, systematic class discussion as learners would only be involved to the extent that they would listen and take notes while thinking about the teacher's analysis of the photo (Fritschner, 2000). Then, when the facilitator asked if they had questions, or that they ask questions, only a few learners would participate. During such a session, every answer would rely heavily on the facilitating teacher.

Deliberation in the classroom is widely used and highly valued for actively engaging learners in their own learning (Cooper, 1995). Recent studies have demonstrated that cold-calling, or calling on a learner whose hand is not raised, increases the number of learners who participate voluntarily in class discussions and does not make them uncomfortable (Dallimore, Hertenstein & Platt, 2013; Doty, Geraets, Wan, Saitta & Chini, 2020). Participation in discussion leads to learning, including providing learners with opportunities to develop and practise essential skills such as organising concepts, formulating arguments, evaluating evidence and responding to ideas thoughtfully and critically (Davis, 2009). It further allows learners to experience a realistic context (Liang, & Wang 2004) and master the language and thinking of a discipline (Krupnick, 1985). The strategy entails engaging learners in the analysis of images. In this case, it will be used to analyse a photo image in the History classroom.

Testing this strategy in the teacher training institution's microteaching practices, the team was convinced that with careful application, the strategy would resonate with the teaching of more topics in History to help learners reach their potential. The group believed that this strategy would propel learners of History to a positive developmental and academic path in the subject.

As History learners, like any other learners, process information through both visual and auditory memory, presenting historical information in these formats could maximise learners' capacity to receive and process new information (Sundar, 2020).

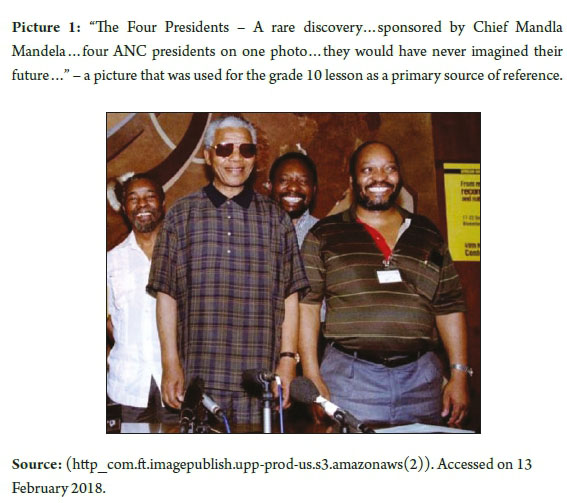

As a strategy used in class to analyse historical images, the PST consists of asking learners to examine "The Four Presidents" (see picture 1 below). Instead of an expert lecture, the PST strategy is used to analyse this image and construct its meaning about the recent past. In its use, the PST is coupled with a think-pair-share structure as a means to support discussion/participation by learners. The think component involves learners taking ownership of their contribution, while the pair component allows for sharing and discussion of their ideas with a fellow learner, to give them confidence that they can contribute to a discussion with the whole class (Drake & Nelson, 2005:175).

The teacher then gives learners a time limit (such as five minutes) to discuss the geographic, social, economic and political themes they believe are defined and underpinned by the image. Questions range from those that suggests to learners that the photo has a purpose and that the photographer is attempting to convey a story or idea in visual or image form, just as the historian conveys an interpretation in written form. These questions allow for creativity and the application of knowledge. It is also a good measure of a learner's sophistication. Such questions allow learners to understand that history happens within a particular context (Linn & Eylon 2006).

The questions are designed to immediately cause learners to examine the photo. The PST strategy has a hidden purpose, which is to find out what learners already know. Learners are supported to participate in a discussion by being allowed a comfortable environment in which to extend their knowledge (when they pair with a classmate and exchange ideas).

Finally, during the share segment (when the teacher or facilitator asks learners the questions provided as a class/group), the teacher can call on any learner, knowing that they have a foundation from which to contribute to the discussion. In essence, learners will be confident that they can succeed because they have thought about the teacher's questions.

This approach to the analysis of a photo parallels the way a written document is studied. The image selection is treated as a historical document and studied using methods that reinforce historical thinking and develop learners' skills of virtual literacy. Treating the photo as a historical document allows teachers and learners to approach it with the traditional tools ofhistorical analysis. One stage in the analysis involves the general analysis of the photo in order to establish as much information as possible about it. While certain data will be evident at first viewing, a more thorough analysis will require that learners explore questions of the photo's content, production, and reception through: (i) a close study of the content of the photo, i.e., people that appear on the photo, their attire, and the way they seem to relate to convey meaning; (ii) an investigation of social, cultural, political, economic, and institutional background of the production and the conditions under which the photo was made; and (iii) an examination of the ways the photo was understood by its original audience (O'Connor, 1987:6).

The many and varied ways in which scholars and teachers have made use of photos and other images can be reduced to four frameworks of historical inquiry: image document as representation of history; as evidence for social and cultural history; as evidence for historical fact; and as evidence for the history of the photo. In its context as a representation of history, a photo is studied as a secondary document, but in the next two contexts it can be used as a primary source.

Firstly, the PST strategy of image analysis incorporates active learning (engagement/ participation), comparative to teacher-centred discussions and lectures. McCarthy and Anderson (2000:279) found that students who participated in collaborative and analysis exercises did better on subsequent standard evaluations than their traditionally instructed peers.

Presented here is a discussion of active learning, descriptions of the two experiments, and an explanation of the outcomes and implications of the study.

In a lecture, learners passively absorb pre-processed information and then regurgitate it in response to questions. There is a need to effect significant change in the passive nature of the History learning experience, which perpetuates learning at the surface (passive) level rather than the deep (active) level. The traditional format encourages students/learners to concentrate on superficial indicators rather than fundamental underlying principles, thus neglecting deep (active) learning. "Traditional" (for the purposes of this study) refers to facilitation of the memorisation of large quantities of information.

Active learning, as represented by the PST method, for example, refers to "experiences in which students are thinking about the subject matter" as they interact with their material, i.e., the photo, the instructor and each other (McKeachie, 1999:44). Human interaction is important, yet instructors too often expect learners to acquire relevant knowledge in a learning environment with little interactive content (Marton & Saljo, 1976). These authors also agree that lecture format will likely continue to be important in the learning process. This only increases the need for balancing passive with active learning. The PST activity requires learners to analyse "The Four Presidents" critically. The activity encourages active participation in learning and is an alternative to passive lecture and the teacher-centred discussion period.

As an active learning technique, PST stimulates inquiry and interest as learners acquire knowledge and skills (Montgomery, Brown & Deery, 1997). It is student-centred, maximises participation, is highly motivational and gives life and immediacy to the subject matter by encouraging learners to move beyond a superficial, fact-based approach to the material.

Bonwell and Eison (1991) note that active learning strategies and techniques help create a more stimulating and enjoyable classroom environment for learners. Teachers must cover large quantities of information/syllabi in a limited period, yet they have an obligation to nurture learners' intellectual skills.

University teacher education experiences alone may have little impact on the future performance of prospective teachers (Slekar, 1998:487). What students learn from their "apprenticeship of observation" may be deeply embodied in their belief system (Slekar, 1998:488). At these schools, student teachers observed existing methods that challenged their new beliefs about teaching and conflicted with university teacher-education programmes. The context at these schools challenged student teachers into reflective conservatism - a reflex action to consider more familiar approaches to teaching when confronted with new and unfamiliar teaching methods (Slekar, 1998:488).

Research methodology

Research design

The research design involved gathering data during eight weeks of teaching practice evaluations at a few schools offering History in and around Mankweng Township in Polokwane. Research was conducted using an analytical research approach. Primary data were collected conveniently (Salkind, 2006; Leedy & Ormrod, 2006; Welman, Kruger & Mitchell, 2005) from a sample of History learners at a few schools in the township. These were the same schools where teacher trainees were deployed for their teaching practice over a period of eight weeks. Therefore, both the learners and the mentor teachers were conveniently available.

Two types of data were collected and integrated. A pre-photo viewing survey was administered in the first two weeks of teaching practice, followed by two periods of observation of the learners' behaviour in weeks 3 and 4. During weeks 5 and 6, learners viewed, discussed and analysed the photo image. Finally, a post-viewing survey was administered during the last two weeks of teaching practice.

The pre-viewing survey was meant to gather information on learners' attitudes and behaviours related to class participation in History lessons prior to viewing the photo. The post-viewing survey focused on learners' attitudes and behaviours related to class participation during and after viewing the photo. Therefore, data on learners' perceptions were collected using interviews both before and after the photo viewing and analysis.

Observations formed a critical part of the methodology (Salkind 2006; Leedy & Ormrod, 2006; Welman, Kruger & Mitchell, 2005). It was important to observe first-hand the extent to which learners' behaviour was being affected on a daily basis. Observation notes were taken during the session and refined immediately thereafter, with inferences and interpretations regarding what transpired as learners acted and interacted with the facilitator, the image and the questions posed. From these data, a picture was constructed of new levels of energy among the learners. The observation records took a descriptive form in order to maintain some level of objectivity by considering actuality. So, to some extent, mixed methods were applied as both qualitative and quantitative (descriptive) approaches were deployed, using an array of interpretive techniques to describe learner behaviours and decode, translate and construct meanings using units such as photos and groups of learners. These data were later to prove critical when the perceptions of a few learners were collated for corroboration.

Specific lesson sessions were selected for observation because they were devoted to image analysis and deliberate discussions. A responsible student teacher observer was assigned to each lesson session. All observers were trained to categorise questions in terms of levels of difficulty and to record data as learners responded. For each question asked, the observer noted whether the learners voluntarily raised their hands and participated or the facilitator cold-called before the learner could respond.

Learners had been given identity numbers at the beginning of the research study and retained the same numbers throughout. This was important for easy of reference and monitoring the behaviour of each learner pre- and post-photo viewing and analysis survey. Using the identification numbers, pre- and post-viewing surveys were matched for 103 learners. All learners present for the first and second observations at were still present during the two class lessons observed, mainly due to the interest aroused by the photo image lessons.

Data analysis and findings

The primary focus in this study was to assess differences in learners' behaviour during deliberative class discussions pre- and post-photo viewing in response to PST as a method of encouraging learners to participate in analysis of an image. Based on observations of the percentage of learner participation in discussions before photo viewing, the percentage of learner participation during and after viewing the photo had improved. The improvement could be attributed to several factors ranging from the use ofvisual source material on which questions were based to the realisation that, indeed, History is about people who lived in particular spaces at particular times, thus exposing learners to a hybrid form of presentation different from the traditional form of lecture delivery to which they are accustomed. All of these factors were seen to have aroused learners' interest in the History subject matter.

Findings noted that with careful crafting of questions, learners responded voluntarily to visuals by raising their hands and not only engaging with the teacher but with their fellow learners as well. It was also observed that an increased number of learners responded comfortably to PST during class discussions. It was interesting to note that in their engagement with the discussion of the image, some learners were prompted to remember some of former President Mandela's speeches and former President Mbeki's robust debates on the issues of HIV and AIDS. One learner even noticed absence of former President Kgalema Motlanthe from the picture, even though he only served on an interim basis. Teacher mentors have also shown interest in this strategy as learners seemed lively in class, with disinterest turning into interest as learner participation increased.

From the perspective of some of the learners interviewed, it was concluded that straightforward teacher-centred and textbook-based approaches perhaps meant history is objective (objectivist history). Images allow learners to make their own discoveries and become experts in their own right. Use of images encourages guided reflection in learning.

Limitations

The results presented must be interpreted in the light of the research limitations. The data were gathered at selected schools. Eight weeks was obviously not enough time to make a compelling judgment on the achievement of the set objectives. Thus, whether the results could be generalised to more schools is not clear yet. Unfortunately, due to the Covid-19 situation, which limited the period of study, the effect of PST on objective measures of learning such as final summative grade scores for individual learners could not be examined.

Due to the small number of schools offering History in the targeted area, only a few teachers and learners could be conveniently sampled. The findings range from a lack of exposure to quality competency in History teaching strategies, which results in elements of incompetency, to a lack of quality historical material resources and challenges of at-home assistance with the subject due to high levels of illiteracy and language deficiency.

In conclusion, when History subject results are blamed for, among other things, negatively affecting the performance of schools, the result is often the scrapping of the subject from the school's curriculum. Furthermore, the Department of Basic Education is often blamed for not providing adequate school resources and infrastructure for the creation of a conducive learning environment and delivery of quality education and learning overall. This study recommends that teachers be exposed to continuous enrichment programmes in History teaching and delivery strategies and that conditions in schools be improved to enhance levels of teaching and learning overall.

Conclusion

This study investigated whether the PST strategy of image analysis affected learners' behaviour in relation to the subject History in selected schools. In particular, two areas explored were the effect of PST on the voluntary participation of History learners in the classroom as well as its effect on their comfort with responding to being cold-called to respond to questions. To assist the learners, the study emphasised the use of the PST strategy of image analysis. During the pre- and post-photo viewing lesson sessions, trained observers gathered data on whether learners voluntarily participated and contributed to deliberative discussions or facilitators called on learners. In addition, data were gathered using pre- and post-photo viewing surveys regarding learners' perceptions about and behaviours related to deliberative discussion in the History class.

The primary results indicated that in the use of at least the photo image, a larger percentage of learners participated voluntarily, with a somewhat-increased number responding comfortably to being cold-called by the facilitators or teachers to voice their opinions. The study makes a valuable contribution to the discussion on how History as a subject can contribute to improved school performance generally and to the use of PST as an instructional strategy in encouraging individual learners to engage in the subject of History in particular. It has further demonstrated that learners can, of their own volition, choose to contribute during History class discussions without the necessity of teachers calling on them and that learners can in turn respond to being called without feeling discomfort, provided the right resources are provisioned. Recognising that both the pre-and post-photo viewing surveys have shown a strong linkage between learner participation frequency and learning, it is recommended that all learners of History be motivated to participate in deliberative lesson discussions through strategic means.

References

Armstrong, M & Boud, D 1983. Assessing participation in discussion: An exploration of the issues. Studies in Higher Education, 8(1):33-44. [ Links ]

Bonwell, CC & Eison, JA 1991. Active learning: Creating excitement in the classroom. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Reports. [ Links ]

Brookfield, SD & Preskill, S 2012. Discussion as a way of teaching: Tools and techniques for democratic classrooms. John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Cooper, PJ 1995. Communicationfor the classroom teacher (5th ed.). Scottsdale, AZ: Forsuch Scarisbrick. [ Links ]

CAPS 2011. National policy pertaining to the programme and promotion requirements of the National Curriculum Statement Grades R-12. [ Links ]

Dallimore, EJ, Hertenstein, JH & Platt, MB 2013. Impact of cold-calling on student voluntary participation. Journal of Management Education, 37(3):305-341. [ Links ]

Dancer, D & Kamvounias, P 2005. Student involvement in assessment: a project designed to assess class participation fairly and reliably. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 30(4):445-454. [ Links ]

Davis, BG 2009. Tools for teaching (2nd ed.) San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Doty, CM, Geraets, AA, Wan, T, Saitta, EKH & Chini, JJ 2020. Student perspective of GTA strategies to reduce feelings of anxiousness with cold-calling. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Tong_Wan4/publication/338555773. Accessed on 30 September 2020. [ Links ]

Drake, FD & Nelson, LR 2005. Engagement in teaching History: Theory and practices for middle and secondary teachers. Pearson, Ohio. [ Links ]

Fritschner, LM. 2000. Inside the undergraduate college classroom: Faculty and students differ on the meaning of student participation. Journal of Higher Education, 71(3):342-362. [ Links ]

Krupnick, CG 1985. Women and men in the classroom: Inequality and its remedies. Journal of the Harvard Danforth Center, 18-25. [ Links ]

Leedy, PD & Ormrod, JE 2005. Practical research planning and design (8th ed.). Pearson Education International, New Jersey. [ Links ]

Liang, N & Wang, J 2004. Implicit mental models in teaching cases: An empirical study of popular MBA cases in the United States and China. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 3(4):397-413. [ Links ]

Linn, MC & Eylon, BS 2006. Science education. In: PA Alexander & PH Winne (eds.). Handbook of educational psychology, 2nd edition. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. [ Links ]

McCarthy, JP & Anderson, L 2000. Active learning techniques versus traditional teaching styles: Two experiments from History and Political Science. Innovative Higher Education, 24(4):279-294. [ Links ]

McKeachie, WJ 1999. Teaching, learning, and thinking about teaching and learning, Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Learning. [ Links ]

Marton, F & Saljo, R 1976. On qualitative differences in learning: I-Outcome and process. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 46(1):4-11. [ Links ]

Montgomery, K, Brown, S & Deery, C 1997. Simulations: Using experiential learning to add relevancy and meaning to introductory courses. Innovative Higher Education, 21:217-229. [ Links ]

O'Connor, JE 1987. Teaching History with film and television: Discussion on teaching no. 2. Washington, DC: American Historical Association. [ Links ]

Rocca, KA 2010. Student participation in the college classroom: An extended multidisciplinary literature review. Communication Education, 59(2):185-213. [ Links ]

Salkind, NJ 2006. Exploring research (6th ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall, New Jersey. [ Links ]

Slekar, TD 1998. Epistemological entanglements: Preservice elementary school teachers' "apprenticeship of observation" and the teaching of History. Theory and Research in Social Education, 26(4):485-507. [ Links ]

Sundar, CK 2020. The student engagement trap, and how to avoid it, Edutopia. Brain-Based Learning, Sept. 17. [ Links ]

Welman, C, Kruger, F & Mitchell, B 2005. Research methodology (3rd ed.). Cape Town: Oxford University Press Southern Africa. [ Links ]