Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Yesterday and Today

On-line version ISSN 2309-9003

Print version ISSN 2223-0386

Y&T n.26 Vanderbijlpark Dec. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2223-0386/2021/n26a1

ARTICLES

Utilizing a Historically Imbedded Source-Based Analysis Model (HISBAM) in the History school classroom

Byron BuntI; Pieter WarnichII

IFaculty of Education, North-West University, Vanderbijlpark, South Africa 20172672@nwu.ac.za Orcid: 0000-0002-2102-4381

IIFaculty of Education, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa pieter.warnich@nwu.ac.za Orcid: 0000-0003-3967-7767

ABSTRACT

This paper aims to elucidate upon a model that imbeds historical skills, concepts and categorizations into a source-based analysis approach utilizing levels of cognitive complexity by combining different types of sources into a coherent system. This model will focus on the South African school context. In this paper, concepts such as cause and effect and chronology will be explored, as well as historical categorizations of social, economic and political history. The taxonomy of source-based questioning will also be highlighted, as well as the variety of sources that could be used in a history classroom. Various theories and perspectives have emerged in the field of History, and these will also be explored to better understand the model in question. The paper will conclude with an in-depth explanation as to how this Historically Imbedded Source-Based Analysis Model could be used in the history classroom and the potential benefits that this model holds.

Keywords: Historiography; Levels of questioning; Cognitive complexity; Source-Based Analysis Model (HISBAM); History classroom; South Africa; Curriculum

Introduction

Using and analysing different types of historical sources teaches history learners to interrogate the past from political, social, economic and other perspectives to compel them to form their own interpretations and narratives (Warnich, 2006:23). The aim is to enable learners to extract, analyse and interpret evidence from sources, just like historians do, and write their own piece of history. The emphasis is therefore on the doing of history as a process rather than a product. (DoBE, 2011:8).

The focus on a source-based approach to the teaching, learning and assessment of history has been in place for several decades. In fact, this approach has been used in History classrooms around the world since 1910 and has been strongly supported in South Africa since the 1970s (Warnich, 2006:23). This source-based approach survived all the revisions of the History curriculum that started in 1994 as part of the democratization of South Africa's educational system, including the last revision in 2011, when the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) of the national curriculum statement (NCS) was promulgated (Reyneke & Bunt, 2022:55-68).

History learners tend to struggle with the interpretation of the sources as they do not always know how to prioritize information in order to extract relevant information to answer questions (compare, for example, GPG, 2019: slide 5; Misipa, 2016:vii). Furthermore, many learners are second- or third-language English speakers with cultural backgrounds quite distinct from those of the authors of the source materials being taught or utilized in exams. As a result, many learners find the source material confusing or incomprehensible. Therefore, cartoons are used sparingly, as teachers do not find them useful (Bunt & Bunt, 2019:42-59).

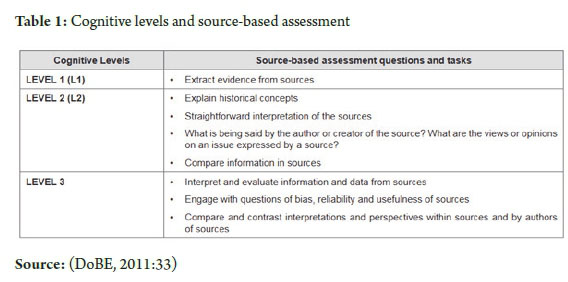

Teachers and examiners responsible for setting source-based questions also sometimes find it difficult to formulate questions based on the taxonomies of cognitive demand that are mostly based on Bloom's revised taxonomy (Anderson & Kratwohl, 2001). For these individuals, it is a challenge to find a common interpretation of the different levels of cognitive demand (see Table 1) as required by the NCS-CAPS (Umalusi, 2018:3,7; Umalusi, 2010:26-27). Furthermore, and as the research data in this article points out, teachers and examiners also struggle to identify appropriate sources that can test a wide variety of historical skills and concepts. An over-reliance on text-based sources or political sources seems to be the order of the day.

The Historically Imbedded Source-Based Analysis Model (HISBAM) seeks to address these issues by combining different types of sources and to achieve a common interpretation of cognitive levels and historical categorizations.

Working with sources in the History classroom: An orientation

Sources are the raw material ofhistory and can be considered as evidence that a certain event occurred (Howell & Prevenier, 2001:17-20). These include artefacts, letters, documents, books, photographs, drawings and paintings, speeches, monuments, statues and buildings, tables and graphs, maps, poems, diaries, songs, etc. (Dalton & Charnigo, 2004:400-425). They can be written, oral, visual or any other material that is useful to the historian to find historical evidence. Historians construct a view of the past by using what has survived to glean information/evidence (Dalton & Charnigo, 2004:400-425). These sources are often classified as primary, secondary or tertiary (Haw, 2016:104).

A primary source is produced at or around the time of the event or after the event by a witness to it (Marwick, 1994:16-23). It can include poems, original artwork, speeches, autobiographies, diaries, etc. It comes from the time the historian is studying and provides learners with opportunities to have a more direct encounter with past events and people (Dalton & Charnigo, 2004:400-425). It links learners to the human emotions, aspirations and values that prevailed in another time (Marwick, 1994:16-23).

A secondary source is written sometime after the event by someone who did not witness it (Camic, Gross & Lamont, 2012:135). It is usually the products of historians, journalists or writers who make use of the available primary and secondary sources in constructing a view of a specific historical event. Textbooks, journal articles, commentaries and encyclopaedias are all examples of secondary sources. Tertiary sources rely almost entirely on secondary sources and represent broad surveys. Dictionaries and Wikipedia are two examples of tertiary sources (Haw, 2016:104). Although knowing whether a source is primary, secondary or tertiary is important, it is more important to explain whether a source is useful or reliable (Dalton & Charnigo, 2004:400-425). Teachers need to get learners to understand that the usefulness of a source depends on the questions that are asked of it.

Perhaps the most important thing to know about these three types of sources is that teachers assess them differently when trying to decide such things as their usefulness and reliability (DoBE, 2011:33). Most of what will be said about reliability refers to primary sources, so what should teachers be looking for when assessing a secondary source? The key features are the reputation of the author and/or publisher, evidence of extensive and balanced research (bibliography and footnotes) and, in the case of historians, some knowledge as to which historical school the historian belongs to (liberal, Marxist, nationalist, post-modern and so forth) (DoBE, 2011:42).

Skills and concept development

Working with sources in the History classroom contributes to the development of learners' historical skills and concept development. According to the History FET NCS-CAPS document (DoBE, 2011:9), several skills can be developed in the subject of History. These include (i) analysis, which is the ability to understand evidence, assess its reliability and recognize bias, prejudice, cause and effect, omissions and irrelevancies, (ii) evaluation, which is the ability to assess the authority of evidence and relate it to its historical context, to recognize bias and inappropriate emotional content, to evaluate human conduct in its historical context and to test hypotheses, (iii) communication, which refers to the ability to communicate using a variety of written forms, to present a case verbally, to pose questions, to discuss and listen and to make valid historical statements through art and drama, (iv) synthesis, which is the ability to select evidence, to analyse facts in sequence, to use historical data to make imaginative reconstructions and to organize material of the past into a coherent narrative, (v) judgment, which is particularly important when learners are asked to assess the reliability of evidence and helps learners arrive at an opinion or give an estimate of reliability that is based on critical reflection, and (vi) extrapolation, which is the process whereby learners learn to come to conclusions about a historical situation using inference from known facts. In so doing, they learn to apply their understanding of a particular period oftime to other historical situations (DoBE, 2011:9; Salevouris, 2015:27-36).

From the abovementioned skills, it is apparent that, in the History classroom, utilizing skills to interpret and communicate ideas based on sources/evidence is of paramount importance. The HISBAM seeks to align these skills into a coherent system in which analysis of sources is carried out holistically. However, certain key concepts need to be clarified further, as these concepts were also imbedded into the HISBAM.

According to the History NCS-CAPS document (DoBE, 2011:10), several concepts are central to the understanding of History. These are (i) similarity and difference, (ii) continuity and change, (iii) cause and effect, (iv) chronology, (v) bias, (vi) empathy and (vii) reliability. The HISBAM is explicitly focused on continuity, change, cause and effect and chronology.

It is critical that learners utilize the abovementioned concepts in order to make sense of sources. The HISBAM incorporates the concepts of continuity, change, cause and effect and chronology in a systematic way, and they are always tested no matter how questions are phrased. The other concepts can be tested in the model, but this depends on how the questions are phrased.

Source specifications: Integrate and differentiate

For a holistic understanding of a certain historical topic/theme, it is necessary for the historical sources to be, as far as possible, an integration and representation of the social, economic and political historiography.

Social history, often called the new social history, is a field of history that looks at the lived experience of the past. A people's history, or history from below, is a type of historical narrative which attempts to account for historical events from the perspective of common people rather than political and other leaders (Tolley, 2017:471-477). A people's history is the history of the world that is the story of mass movements and of the outsiders (Conner, 2009:1-6). Individuals not previously included in other types of writing about history are part of this theory's primary focus, which includes the disenfranchised, the oppressed, the poor, the nonconformists, and the otherwise forgotten people (Tolley, 2017:471-477).

Social history is crucial within the classroom. The fact that our perception of the past changes and is contested makes it all the more important that we are able to make informed judgments about it and defend our own sense of who we are against those who would deny, dismiss or marginalize it (Tilly, 1995:1-17). Social history is a critical part of active citizenship in a democratic society. Growing up in poor or marginalized communities, it can be difficult to develop a sense of pride in where you come from and who you are, still less the sense of agency and possibility necessary to make the most of one's talents and aptitudes and change things for the better (Tilly, 1995:1-17).

Economic history is the study of economies or economic phenomena of the past. Analysis in economic history is undertaken using a combination of historical methods, statistical methods and the application of economic theory to historical situations and institutions (Kindleberger, 1990:13-14). The topic of economic history includes financial and business history and overlaps with areas of social history such as demographic and labour history (Whaples, 2010:17-20).

Economic history is important for History learners, as it is a way to make sense of how people of the past negotiated with the material world around them, including, it should be stressed, other people (hence the common pairing of economic and social history) (Allender, Clark & Parkes, 2020:23-25). Teaching economic history also provides invaluable insight into the big global challenges of today's world and those of the past -whether it is trade wars, colonization, exploitation, financial crises, migration pressures, climate change or extreme political uncertainty (Allender et al., 2020:23-25).

Political history is the narrative and survey of political events, ideas, movements, organs of government, voters, parties and leaders (Percy, Richard & Kirkendall, 2011:110112). Political history studies the organization and operation of power in large societies (Parthasarathi, 2006:771-778) by focusing on the elites in power, their impact on society, popular response and the relationships with the elites in other areas of social history.

An important aspect of political history is the study of ideology as a force for historical change. Percy et al. (2011:110) assert that "political history as a whole cannot exist without the study of ideological differences and their implications". Studies of political history typically centre around a single nation or leader and its political change and development. In particular, the focus on leaders can be linked to The Great Man Theory, which aims to explain history by the impact of "great men", or heroes: highly influential individuals who, due to their personal charisma, intelligence, wisdom, or Machiavellianism, utilized their power in a way that had a decisive historical impact (Faulkner, 2008:57). However, only focusing on this type of history does not give learners an adequate understanding of the forces and events that have shaped the communities in which most of us live (Allender et al., 2020:23-25).

Apart from using historical sources to integrate and represent the social, economic and political historiography, one should also differentiate, as indicated earlier, between various types of primary, secondary and tertiary sources. These must include different types of sources, such as speeches, graphs, diaries, cartoons, poems, etc. (Barton, 2018:1-11).

Source-based assessment and cognitive levels

The extent to which a learner has acquired the key historical skills and developed an understanding of the key historical concepts is usually established through their ability to answer source-based questions set specifically to determine these (DoBE, 2011:33). The questions can be set at three complexity levels. However, in terms of the HISBAM, a fourth level has been added, which will be elaborated upon. The following table outlines the three levels as set out in the History policy document of NCS-CAPS.

As can be seen from the above table, more cognitively complex thinking is required as we move from level 1 to 3. Level 1 merely requires learners to extract answers that are already present in the source, such as "Who is depicted in this photo?". Level 2 requires a straightforward interpretation of a source using a historical concept. Very basic comparisons can be made, usually only with two sources. A question on this level could be "What symbols are being used in this cartoon?" or "What is the view of the author in this text?". Level 3 would require learners to evaluate information from a given source, to assess reliability, bias and usefulness and to make wider comparisons of multiple sources. A question on this level could be something like "Evaluate the cartoonist's message in this cartoon against your own knowledge and state whether you agree with it or not" or "Assess the reliability of this source and elaborate if any bias is present".

The authors suggest that a fourth level be added to this taxonomy, which entails learners synthesizing information from a multitude of sources related to the central topic in question. These types of questions typically link to extended (essay) writing, which is a pivotal form of assessment in the History classroom.

This type of assessment provides an effective means of testing the learner's comprehension of a topic. Learners must show that they have not only acquired knowledge of the topic but also fully understood the topic and the issues it raises. In history, writing an essay provides learners with an opportunity to explore a particular issue or theme in more depth. It should not be simply a list of facts or a description of opinions but a clear line of argument substantiated by accurate and well explained factual evidence gathered from the sources provided and the writer's own knowledge (Van Eeden, 1999:111). Furthermore, extended writing embodies historical thinking as the learner progressively develop skills in research, analysing different forms of source material, using different kinds of evidence, and writing strong, critical and clear arguments (Harris, 2001:13-14; Van Eeden, 1997:98-110)

Using sources as evidence in extended writing does not mean extracting information from them verbatim and putting it in paragraphs; it means extracting evidence from all the sources provided and using it as facts and opinions for your extended writing (Van Eeden, 1999:112). Mere copying of sources is a clear indication that the learner does not understand the question or does not know enough about the topic. Consequently, there is no proof of the application of any historical skills.

Level 4 questions will thus require that learners write an essay for which they will need to collect a wide variety of sources by themselves, prioritize the relevant information, synthesize the gist of the arguments, and sequence them into a coherent piece of writing. This is regarded as the highest level of source-based analysis. However, this is viewed as an overall balance and is not necessarily used in every question on the exam paper.

History as a fundamental science vs an applied science

The subject History has also been the subject of debate relating to its position as either a fundamental or applied science. This debate primarily focuses on whether History as a subject can be applied and whether skills can be developed within the subject (Roll-Hansen, 2009:30). This debate will also be investigated, as the HISBAM utilizes a source-based approach that expects students to apply skills to scrutinize sources. History as an applied science emphasizes constructivist models of learner engagement with the past, a world history encompassing the experiences of a variety of groups and a focus on historical skills and concept development through the scrutiny of sources. Historical thinking, reading and analysing sources, recognizing bias and critical thinking abilities were among the goals of teaching history to learners. Doing history is the main focus (Bertram, 2008:155-177).

Fundamental science (or basic science/pure science) is science that describes the most basic objects and forces, or the relationships between them and laws governing them, such that all other phenomena may, in principle, be derived from them following the logic of scientific reductionism (Schauz, 2014:273-328).

Applied science is the application of scientific knowledge transferred into a physical environment (Roll-Hansen, 2009:30). Examples include testing a theoretical model through the use of formal science or solving a practical problem through the use of natural science (Roll-Hansen, 2009:30).

To the layperson, History mainly revolves around the study of the known actions and decisions of people within their society, especially those actions which have some significance for society. History is defined as communication of knowledge that has been obtained through enquiring (Joseph & Janda, 2008:63). It is important that human societies and their individual past experiences, as well as their collective past and the past of the human individual, be embedded in culture ( Joseph & Janda, 2008:63).

The suggestion that history can also be, and perhaps is mainly suited to being used as an applied science will probably stir some historians. Generally, the modern way of thinking seems to be the other way around, namely that other sciences can be put to use in history. Applied' literally means 'to put to practical use' (Roll-Hansen, 2009:30).

However, many historians argue that history can be applied using various approaches (Bertram, 2008:155-177), particularly with source-based assessment that tests historical skills such as chronology or similarity and difference, which the authors believe in strongly. Historical thinking and skills can be used when analysing sources or engaging in role-play.

When working with sources, it is also necessary to differentiate between the types of sources. Apart from primary, secondary and tertiary sources, the sources should include speeches, graphs, diaries, cartoons, poems, and so forth (Barton, 2018:1-11).

In source-based assessment, students use sources to develop judgments about the past. Due to the need to assess a range of sources, both textual and visual, and integrate them to produce meaningful solutions to historical issues, this inductive approach requires higherorder thinking (Barton, 2018:1-11).

If possible, when illustrating historical events or time periods, for example, the sources utilized must be deliberately selected to pique learners' interest, and learners must be given the opportunity to ponder over them and create their own thoughts and views about the period under discussion. Reducing the use of visual sources such as maps, cartoons and pictures will not motivate learners (Barton, 2018:1-11).

Methodology

In this study, the researchers made use of a document analysis methodology (Maree, 2020:186-187) to gather data that was used to design the HISBAM. Document analysis, like other qualitative research methodologies, is a process of analysing or assessing documents that necessitates the examination and interpretation of data to extract significance, acquire insight and build empirical knowledge (Corbin & Strauss, 2008:1-3; Rapley, 2007:123138). The following policy documents relating to source-based work were analysed: the History NCS-CAPS (FET), Grades 10-12 (DoBE, 2011), the National Protocol for Assessment Grades R-12 (DoBE, 2012) and the History source work and extended writing guide for Grades 10-12 (DoBE, circa 2016). They were mainly studied to acquaint the authors with what these documents envisioned when it comes to the implementation of source-based material in the History class. Other documents analysed were exam papers and their addenda (in which the sources appear) for Grades 10 to 12 from 2017 to 2019. The researchers purposively focused on analysing previous History question papers and addenda to gauge the types of sources being used and familiarise themselves with the questions that were asked based on the sources.

Finding, choosing, evaluating (making meaning of), and synthesizing data contained in documents is part of the analytic method (Bowen, 2009:27-40). Document analysis produces data in the form of excerpts, quotes, or whole portions, which are then organized into main topics, categories and case examples using content analysis (Labuschagne, 2003:100-103).

An interpretivist phenomenological approach was followed, where qualitative document analysis was employed. In an interpretivist approach, the focus is on "...an in-depth understanding ofhow meaning is created in everyday life and the real-world" (Travis, 1999:1042) and the data are not accepted at face value - rather, researchers seek to go beyond this to identify hidden meanings (Newby, 2014:463). Apart from studying the mentioned school policy documents relating to the intended use of source-based material in the history classroom, data were collected by scrutinizing the sources used in past papers in order to identify possible gaps in the types of sources used (overuse of one type), whether all the domains of History were represented by the sources (social, economic and political) and the chronological representation of events depicted in the sources (causes, course and consequences).

Results and discussion

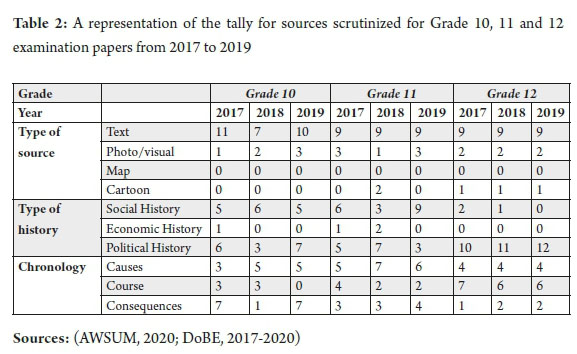

In this section, a tally of the sources found in the addenda of Grade 10 to 12 History examination papers from 2017 to 2019 is outlined and discussed. These papers were set by the DoBE as exemplars for Grades 10 and 11 and national exam papers for Grade 12. Table 2 differentiates the sources into different types, i.e. text, photo/visual, map or cartoon sources. It further differentiates types of history, i.e. political, social or economic history, as well as chronological sources, looking at causes, course or consequences of events.

From the above table, it is clear that the majority of sources (11 out of 12) used in the 2017 History examination for Grade 10 are text sources, with only one being a photo/visual source. This is not representative of the other types of sources, which can give the learners a deeper understanding and value of the subject. Another tendency noted is that of the overuse of socially (5 out of 12) and politically (6 out of 12) focused sources, with only one source being identified as focusing on economic issues. This is a clear gap in how the sources depict an event, as a portion of understanding could be developed by including economic sources. Lastly, the document analysis revealed a tendency to overuse sources that look at the consequences of events (7 out of 12). However, the other two historical concepts of cause (3 out of 12) and course (3 out of 12) were represented in this addendum.

Regarding the 2017 History examination addendum for Grade 11, the majority of sources (9 out of 12) are text sources, with only three being photo/visual sources. This is not representative of the other types of sources. Also noted was the overuse of socially (6 out of 12) and politically (5 out of 12) focused sources, with only one source being identified as focusing on economic issues. This shows a clear gap in how the sources depict an event, as a portion of understanding could be developed by including economic sources. However, a positive note is that this addendum had a healthy balance of social, economic and political sources.

For the 2017 History examination for Grade 12, again, a predominance of text sources is evident (9), with only two visual sources and one cartoon. In terms of the types ofhistory covered, political sources dominated, with ten sources. Only two social sources were used and no economic sources were consulted. In terms of chronology, only one source focused on the consequences of events, with four focusing on causes and the majority (7) focusing on the course of an event.

From the above table, it is clear that the majority of sources (7 out of 9) used in the 2018 Grade 10 History examination addendum are text sources, with only two being photo/visual sources. This is not representative of the other types of sources, representing a continuing trend from the 2017 paper. Also noted is a tendency to overuse socially (6 out of 9) and politically (3 out of 9) focused sources, with no source being identified as focusing on economic issues. This is a clear gap in how the sources depict an event and also continues the trend seen in 2017. Lastly, the document analysis revealed a tendency to overuse sources looking at the causes of events (5 out of 9), while the course of an event was depicted in three out of the nine sources. Only one source in the 2018 paper focused on consequences, as opposed to the 2017 paper, where the majority of sources focused on effects. This shows no clear consistency in source selection.

Regarding the 2018 History examination addendum for Grade 11, the majority of sources (9 out of 12) are text sources, with only two being cartoon sources and one being a photo/visual source. This is not representative of the other types of sources, representing a continuing trend from the 2017 paper. However, it is noted that this addendum did try to use cartoons, which can offer deep insight into events. Another tendency noted is that of the overuse of political (7 out of 12) focused sources, with the rest focusing on social and economic sources. Lastly, the document analysis revealed a tendency to overuse sources looking at the causes of events (7 out of 12), while the course of an event was depicted in three out of the 12 sources. Only two sources in the 2018 paper focused on the course, as opposed to the 2017 paper, where the sources were more evenly balanced.

For the 2018 History examination for Grade 12, again, a predominance of text sources is evident (9), with only two other visual sources and one cartoon. In terms of the type of history covered, political sources dominated, with 11 sources. Only one social source was used and no economic sources were consulted. In terms of chronology, only two sources focused on the consequences of events, with four focusing on causes and the majority (6) focusing on the course of an event.

From the above table, it is clear that the majority of sources (9 out of 12) used in the 2019 Grade 10 History examination addendum are text sources, with only three being a photo/visual source. This again represents a trend of overuse of text sources. Another tendency noted is that of the overuse of socially (5 out of 12) and politically (7 out of 12) focused sources, with no source being identified as focusing on economic issues. This tendency has repeated since the 2017 paper. Lastly, the document analysis revealed a tendency to overuse sources looking at the causes (5 out of 12) and consequences of events (7 out of 12). No source focused on the course of events. Once more, consistency is not evident in source selection.

Regarding the 2019 History examination addendum for Grade 11, the majority of sources (9 out of 12) are text sources, with only three being photo/visual sources. This again represents a trend of overuse of text sources. Another tendency noted is that of the overuse of socially (9 out of 12) and politically (3 out of 12) focused sources, with no source being identified as focusing on economic issues. With the Great Depression as a topic, it would have been easy to find economic sources. This tendency has repeated since the 2017 paper. Lastly, the document analysis revealed a tendency to overuse sources looking at the causes (6 out of 12) and consequences of events (4 out of 12). Only two sources focused on the course of events. Once more, consistency is not evident in source selection.

For the 2019 History examination for Grade 12, the same pattern emerges, with a predominance of text sources (9), only two visual sources and one cartoon. In terms of the type of history covered, political sources dominated, with 12 sources. No social or economic sources were consulted. In terms of chronology, only two sources focused on the consequences of events, with four focusing on causes and the majority (6) focusing on the course of an event. This is the same pattern as in the 2018 paper.

To summarize the above findings, it is clear that in all three grades, there is an overemphasis of text-based sources, with only some use of photo/visual sources. There were cases where cartoons were used, but these were extremely rare, normally only constituting one out of a number of sources. In terms of historical category, another clear trend is the overuse ofpolitical history, with only some focusing on social history. Economic history is the most underused type. In terms of chronology, it was evident that the focus of sources changed over the years from causes, to course, to consequences. This could be misconstrued as a positive finding; however, there is no consistency. It is important to have equal numbers of each of these sources to properly test cause and effect.

Therefore, from the above document analysis, it is clear that a more consistent framework of source selection ought to be utilized when setting up exam papers. To ameliorate this, the HISBAM is proposed.

The following section will delineate the HISBAM in depth.

The HISBAM

Based on the aforementioned discussion on history as an applied science, the authors wish to elaborate upon a model that seeks to develop an applied approach to source-based analysis, which imbeds chronology and cause and effect within the main historiographical categories of social, economic and political history.

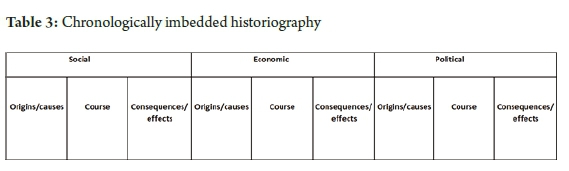

Table 2 below displays the floor plan of the broader HISBAM as the three historiographies of social, economic and political history are the focus of this approach. The idea of chronology, as well as cause and effect, which are essential skills used in history, are imbedded in each historiography. This model can be used when looking at historical events, individuals who played a significant part in history, or historical institutions or groups of people. Therefore, the social history component will have issues surrounding origins or causes of events being dealt with explicitly, followed by the general course of the event/ person's career, as well as the effects or consequences of that event/person on history.

The same type of approach is used for the economic and political historiographies, with chronology, as well as cause and effect, imbedded explicitly in both. The reason for this approach is that, most often, when history teachers use sources in their assignments or exams, they tend to overuse one type of historiography and neglect others. This notion was proven in Table 2, where history exam papers were scrutinized. So, for example, a teacher would focus on political sources that narrowly address the event or topic, which is to the detriment of learners as they are provided with a narrow view of the period. This approach holistically focuses on the three major historiographies, allowing the teacher to utilize all sources on a time period to allow for greater learner comprehension. The learners can thus be exposed to sources that teach them how society looked and operated at the time, how the economy functioned and how the political landscape functioned, including ideologies.

The use of chronology and cause and effect is also useful in each historiography. Again, teachers might favour sources that only look at the origins of an event/historical figure and not ones that look at the general course of an event or the consequences. The HISBAM stipulates from the outset that all sources chosen must be chronologically progressive and represent different times during the event. This helps learners compare and differentiate between the causes, course and consequences.

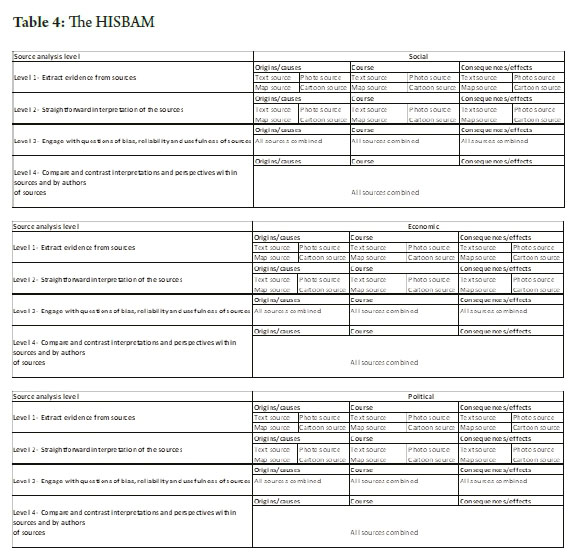

Table 4 further analyses the HISBAM in terms of social, political and economic historiography and how different types of sources and levels of questioning can be imbedded to further optimize source-based analysis in the History classroom.

The above table displays the basic premise of the HISBAM. At its core, the model merges the different levels of source-based analysis (levels 1-4) with the three major historiographies of social, economic and political history. As mentioned in the previous section, chronology and cause and effect are imbedded in all three historiographies. However, the approach is deepened when looking at each source-based level and what types of sources are used for each level.

Therefore, under the social history table, the division of chronology and cause and effect is stratified according to the source analysis level. At level 1, a History teacher can accumulate sources of social history on a given theme, based on origins/causes, course and consequences. In so doing, the History teacher may collect a wide variety of sources, such as texts, photographs, maps, graphs or political cartoons. When setting questions at level 1, learners only need to extract evidence from these sources, so the teacher would use each source separately to set basic questions. This is then done for the economic and political historiographies as well.

Moving to level 2, teachers would still need to accumulate different kinds of sources, but now the type of questions posed can include at least two sources, which require straightforward interpretations of the sources. So now, the origins of social history, as well as the course and consequences, can be interpreted for a particular theme.

When assessing on level 3, all sources are combined for the causes, course and consequences separately. Level 3 questions involve engaging with issues of bias, reliability and usefulness of sources. Here, learners could engage with all the sources pertaining to the origins of an event and compare the sources for usefulness and bias.

Finally, level 4 questions assess the entire chronological progression, using all sources to arrive at an answer. This includes combining sources relating to the origins/causes, course and consequences/effects to test learners' ability to compare and contrast interpretations and perspectives within sources, normally taking the form of an essay. This would require a lot of research on the part of the learner, and therefore a multitude of sources are necessary. The advantages of essay-writing have already been discussed and are directly related to assessment in the History classroom.

When moving between levels, the same sources used in level 1 may be used for levels 2 and 3 as the types of questions asked will change and test deeper insight and comprehension.

A practical example of the operationalization of the HISBAM

In this section, the practical operationalization of the HISBAM will be illustrated using one of the categorizations of history. Economic history was chosen because it was found to be underutilized in the scrutinized history examination papers. Each source will also be "tagged" as depicting the cause, course or consequence of World War 2 on the Nazi German economy.

From the HISBAM, the four levels of questioning determine how deep the questions will be and how many sources are needed. The following questions will link to the sources and comprise all four levels. The content relates to World War 2, specifically Nazi Germany.

Question 1 - level 1

From source A, who were the so-called undesirables that were forced to work as slaves in the camps? (6)

Question 2 - level 1

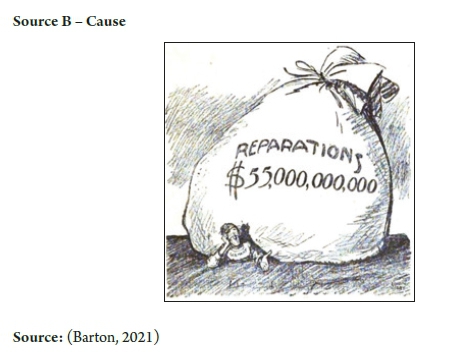

From source B, what does the size of the bag compared to the size of the man represent? (2)

Question 3 - level 2

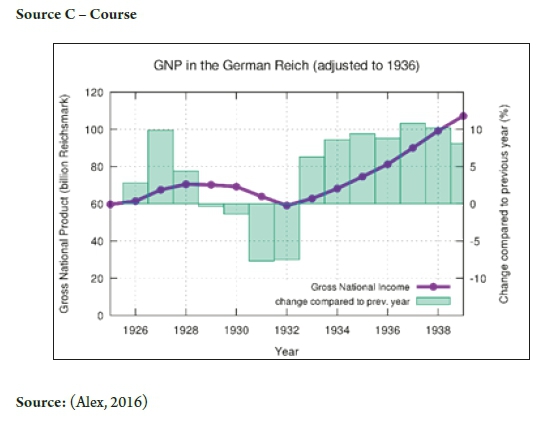

From sources C and E, what can be learned from the Nazi German economy between the years 1934 and 1938? (5)

Question 4 - level 3

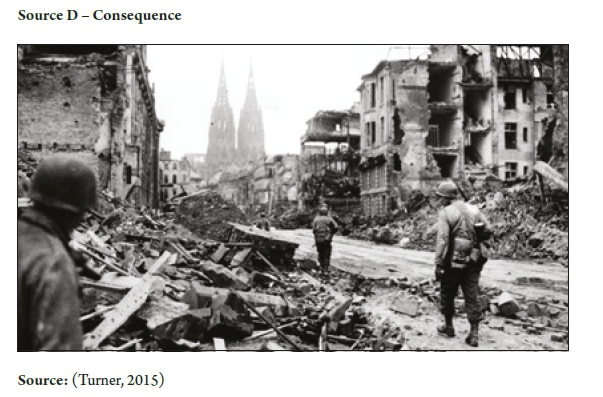

Using sources D and F, evaluate the consequences ofWorld War 2 on the German economy. (10)

Question 5 - level 4

Using all the sources provided, write an essay on the chronology of events that took place in Germany between the years 1934 and 1945. (50)

From the above example, only the economic sources were used, but the exact same approach would be used for social and political sources.

Conclusion

It is the belief of the authors that using the HISBAM for the assessment of sources in the History classroom holds tremendous benefits for History education in South Africa. If History teachers are able to explicitly assess chronology and cause and effect, as well as all three major historiographies, it will enhance learners' understanding of any historical theme presented to them. According to the study's findings, History examinations have an undesirable imbalance in that they ignore economic concerns while being too dependent on textual sources. Historical patterns and the fact that young people are increasingly getting their knowledge about history from visual rather than textual sources make these problems critical today. The HISBAM may be used to monitor these imbalances (perhaps both in examinations and in ordinary classwork).

However, the authors want to acknowledge that this form of "doing" history might have its challenges. One of these is that it will be a very time-consuming process, especially looking for the appropriate sources in the three historiographies (social, economic and political). Although the authors sympathize, they are of the opinion that the HISBAM provides an opportunity to experiment with the compulsory source-based assignments required to compose the continuous assessment mark in History.

The authors also want to acknowledge that the current CAPS curriculum is very prescriptive and loaded and that, at the moment, trying to give equal weight to all forms of History might be considered an unrealistic expectation. There simply isn't the time or space for History teachers to give every topic the comprehensive, complex treatment espoused in this paper. Perhaps the examiners could push the boundaries. Any major change in education is examination-led. Therefore, perhaps History examiners could look at trying to implement the HISBAM at the Grade 12 level and leading the process.

Perhaps the creators of the new History curriculum, which will be published in the near future, should use this approach to guide their content selection and the direction of CAPS content in the future.

References

Alex, A 2016. Germany's gross national product (GNP) and GNP deflator, year on year change in percentages, from 1926 to 1939. [image] Available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economy_of_Nazi_Germany#/media/File:Bruttosozialprodukt_im_dt._ Reich_1925-1939.svg. Accessed on 14 September 2021. [ Links ]

Allender, T, Clark, A & Parkes, R (eds.) 2020. Historical thinkingfor History teachers: A new approach to engaging students and developing historical consciousness. Crows Nest: Allen and Unwill. [ Links ]

Anderson, LW & Krathwohl, DR 2001. A taxonomy for learning, teaching and assessing: A revision of Bloom's taxonomy of educational objectives. New York: Longman. [ Links ]

Awsum 2020. Past exam papers - Grade 11- History. Available at https://www.awsumnews.co.za/exam-papers/past-exam-papers-grade-11-history/. Accessed on 10 September 2021. [ Links ]

Barton, KC 2018. Historical sources in the classroom: Purpose and use. HSSE Online, 7(2):1-11. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334286223_Historical_Sources_in_the_Classroom_ Purpose_and_Use. Accessed on 10 September 2021. [ Links ]

Barton, R 2021. War reparations [image]. Available at http://rbarton.weebly.com/war-reparations.html. Accessed on 14 September 2021. [ Links ]

Bertram, C 2008. Doing history? Assessment in history classrooms at a time of curriculum reform. Journal of Education, 45:155-177. [ Links ]

Bowen, GA 2009. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(2):27-40. [ Links ]

Bunt, BJ & Bunt, LR, 2019. Developing a serious game artefact to demonstrate World War II content to History students. Yesterday&Today, (22):42-59. [ Links ]

Camic, C, Gross, N & Lamont, M (eds.) 2012. Social knowledge in the making. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Conner, CD 2009. A people's history of science: Miners, midwives, and "low mechanicks". New York: Bold Types Books. [ Links ]

Corbin, J & Strauss, A 2008. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory, 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Dalton, MS & Charnigo, L 2004. Historians and their information sources. College & Research Libraries, 65(5):400-425. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education (DoBE). See South Africa. Department of Basic Education. [ Links ]

Faulkner, R 2008. The case for greatness: Honorable ambition and its critics. New haven, CT:Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Gauteng Provincial Government (GPG) 2019. History report 2019. Report on marking Grade 12, December 2018. Available at https://www.google.com/l?sa=t &rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwiDveP7s_HyAhUoQ0EAHVx3Bb8QF noECAUQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.ecexams.co.za%2F2019_Assessment_Instructions %2FChief%2520Markers%2520Report%2FHistory%2520P2.pdf&usg=AOvVaw2geXMOi5C_iJxs3TKnOZzc. Accessed on 10 September 2021. [ Links ]

Grabowski, W 2009. Raport. Stratyludzkie poniesione przez Polske w latach 1939-1945 [Human causalities in Poland between 1939-1945]. In: W Materski & T Szarota (eds.). Straty osobowe i ofiary represji pod dwiema okupacjami [Poland 1939 - 1945. Causalities and repression victims under two occupations]. Warsaw: Institute of National Remembrance (IPN). [ Links ]

Harris, R 2001. Why essay-writing remains central to learning history at AS level. Teaching History, 103:13-16. [ Links ]

Haw, S 2016. A systematic method for dealing with source-based questions. Yesterday&Today, 15:103-115. [ Links ]

Howell, MC & Prevenier, W 2001. From reliable sources: An introduction to historical methods. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

Hughes, TA & Royde-Smith, JG 2021. "World War II": Encyclopedia Britannica. Available at https://www.britannica.com/event/World-War-II. Accessed 14 September 2021. [ Links ]

Joseph, BD & Janda, RD (eds.) 2008. The handbook of historical linguistics. Malden, MA: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Kindleberger, CP 1990. Historical economics: Art or science? Berkeley: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Labuschagne, A 2003. Qualitative research: Airy fairy or fundamental? The Qualitative Report, 8(1):100-103. [ Links ]

Maree, K 2020. The qualitative research process. In: K Maree (ed.). First steps in research, 3rd edition. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Marwick, A 1994. Primary sources: Handle with care. In: M Drake & R Finnegan (eds.). Sources and methods for family and community historians: A handbook. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Misipa, M 2016. Challenges faced in the teaching and learning of source-based questions in history at ordinary level: A case study of a rural school in Lupane district. Unpublished BEd dissertation. Zimbabwe: Midlands State University. [ Links ]

Newby, P 2014. Research methods for education, 2nd edition. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Parthasarathi, P 2006. The state and social history. Journal of Social History, 39(3):771-778. [ Links ]

Percy T, Richard S & Kirkendall, RD 2011. The organization of American historians and the writing & teaching of American history. Teaching History: A Journal of Methods, 36(2):110-112. [ Links ]

Rapley, T 2007. Doing conversation, discourse and document analysis. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Reyneke, M & Bunt, B 2022. The South African school curriculum and assessment. In: P Warnich (ed.). Meaningful assessment for 21st century learning. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Roll-Hansen, N 2009. Why the distinction between basic (theoretical) and applied (practical) research is important in the politics of science. London school of Economics and Political Science, contingency and dissent in Science project. [ Links ]

Salevouris, MJ 2015. The methods and skills of history: A practical guide, 4th edition. New York: Wiley Blackwell. [ Links ]

Schauz, D 2014. What is basic research? Insights from historical semantics. Minerva, 52(3):273-328. [ Links ]

South Africa. Department of Basic Education (DoBE) 2011. Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement, Grades 10-12. Pretoria: Government Printing Works. [ Links ]

South Africa. Department of Basic Education (DoBE) 2012. National protocol for assessment grades R-12. Pretoria: Government Printing Works. [ Links ]

South Africa. Department of Basic Education (DoBE) circa 2016. History source work and extended writing guide for grades 10-12. Available at file:///C:/Users/12923079/ Downloads/History%20Notes%20(3).pdf. Accessed on 5 September 2021. [ Links ]

South Africa. Department of Basic Education (DoBE) 2017-2019. Matric Exams Revision. Available at https://www.education.gov.za/Curriculum/NationalSeniorCertificate(NSC)Examination s/NSCPastExaminationpapers.aspx. Accessed on 10 September 2021. [ Links ]

Tilly, C 1995. Citizenship, identity and social history. International Review of Social History, 40(S3):1-17. [ Links ]

Tolley, H 2017. An indigenous peoples' history of the United States (book review by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz). Human Rights Quarterly, 39(2):471-477. [ Links ]

Travis, J 1999. Exploring the constructs of evaluative criteria for interpretivist research. In: B Hope & P Yoong (eds.). Proceedings of the 10th Australasian conference on information systems. Wellington: New Zealand. [ Links ]

Turner, L 2015. Bomber command maps reveal extent of German destruction [image] Available at https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-34467543. Accessed on 14 September 2021. [ Links ]

Umalusi 2010. From NATED 550 to the new national curriculum: Maintaining standards in 2009. Available at https://www.umalusi.org.za/docs/research/2010/ms_overview.pdf. Accessed on 15 August 2021. [ Links ]

Umalusi 2018. Exemplar book on effective questioning History. Compiled by the Statistical Information and Research (SIR) unit. Available at https://www.umalusi.org.za/docs/reports/2018/History%20March%202018.pdf. Accessed on 30 August 2021. [ Links ]

Van Eeden, ES 1997. Historiographical and methodological trends in the teaching and curriculum development process of history in a changing South Africa. Historia, 42(2)5:98-110. [ Links ]

Van Eeden, ES 1999. Didactical guidelines for teaching history in a changing South Africa. Potchefstroom: Keurkopie Uitgewers [ Links ]

Warnich, P 2006. The source-based essay question (SBEQ) in History teaching for further education and training phase. Yesterday&Today, March, special edition. [ Links ]

Whaples, R 2010. Is economic history a neglected field of study? Historically Speaking, 11(2):17-20. [ Links ]