Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Yesterday and Today

On-line version ISSN 2309-9003

Print version ISSN 2223-0386

Y&T n.25 Vanderbijlpark 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2223-0386/2021/n25a6

ARTICLES

Heads of Department's role in implementation of History syllabi at selected Zimbabwean secondary schools: an instructional leadership perspective

Walter Sengai

National University of Lesotho, Roma, Lesotho. waltersengai@gmail.com; Orcid: 0000-0002-4817-5649

ABSTRACT

This qualitative study explores the school-based instructional leadership role of Heads of Department (HODs) in the implementation of different History syllabi. It seeks to establish the practices that History HODs carry out in order to improve the teaching and learning of the subject. HODs are subject specialists who are responsible for establishing and ensuring high standards of teaching and learning in their subjects. This study is a response to the claim that History HODs often fail to rise to expectations in ensuring effective curriculum implementation in the subject. Qualitative data was collected through the study of circulars and policy documents and by conducting structured, in-depth interviews with fifteen key informants sampled from selected schools in the Glen View/Mufakose district in Harare. The key finding from this study is that the HODs were the de facto instructional leaders during the implementation of the History syllabi and that their level of involvement determines the success and/or failure of History syllabi. The paper concludes by asserting that HODs play a critical role in the implementation of History syllabi, since they are at the chalk face and directly supervise the implementation of changes in the subject as illustrated at five secondary schools used in the study.

Keywords: HOD; Instructional leadership; Implementation; History Syllabus; Supervision.

Introduction

One of the universally central issues facing modern education is the inculcation of a culture of effective teaching and learning (Grissom, Loeb & Master, 2013). Such a thrust has resulted in the acknowledgement of the key role played by Heads of Department (HODs) as instructional leaders in the effective improvement of schools (Jinga, 2016; Manaseh, 2016; Mpisane, 2015). HODs are given different names in different countries in the world. In the United States of America (USA), they are referred to as departmental chairs while in the United Kingdom they are known as curriculum coordinators or subject leaders. In South Africa, they are referred to as departmental heads or middle managers (Bambi, 2012). In Zimbabwe, they are known as heads of department. In this study, the acronym 'HOD' will be consistently used. As part of a school's management, HODs have a responsibility to create and sustain conditions under which quality teaching and learning can take place (Smith, Mestry & Bambie, 2013). HODs' management tasks include planning, organising, coordinating, and controlling (Everard, Morris, & Wilson, 2004). These tasks underpin the daily activities of HODs (Bush, 2008). The idea is that HODs work closer with the teachers, therefore HODs should be the catalysts in supervising teaching and learning (Mpisane, 2015). HODs therefore have a direct impact on the implementation of syllabi in the subject area.

In modern education trends, school heads are no longer the sole instructional leaders of schools (Moreeng & Tshalane, 2014). Instructional leaders, such as HODs, have been continuously empowered to execute contemporary instructional practices by properly and routinely supervising teachers so as to ensure maximum benefits for learners during curriculum implementation (Sengai, 2019). The central role of HODs, as instructional leaders in the daily operations of a school and the impact they have on the tone and ethos which are conducive to teaching and learning in the school, is critical in the process of building a sound culture in curriculum implementation. Ideally, HODs are the academic leaders in their disciplines, and they work closely with their school heads and other HODs to deliver strategic objectives of their school (Tapala, 2019). Their specific role is to provide leadership in relation to discipline specific matters in the school.

Purpose of the study

This study was motivated by the enthusiasm to unpack the instructional leadership practices that History HODs use to improve instruction in the subject during the implementation of different syllabi. The main research question that this study addresses is: what is the role of Heads of Department (HODs) in the implementation of different History syllabi? Apparently, HODs have not yet been fully acknowledged as key instructional leaders, yet they do the bulk of work as they supervise teaching and learning (Mpisane, 2015). The school head claims all the credit if a school performs well academically, forgetting that HODs are the driving force behind the success of teaching and learning (Bush, Joubert, Kiggundu & Van Rooyen, 2010). HODs do this by monitoring teachers' work inside and outside classrooms and by talking and listening to teachers. HODs are the leaders of learning, as they spend a lot of time on the supervision of teaching and learning and mentoring teachers, thereby making a huge impact on improving teaching (Mpisane, 2015). This study unpacks the appointment of History HODs, their perceived roles and responsibilities, the regularity of their supervision of the History teachers, as well as the different approaches they employ to ensure the effective implementation of different syllabi.

Review of related literature

Several studies have been conducted on the different roles of HODs (Tapala, 2019; Jinga, 2016; Malinga &Jita, 2016; Manaseh, 2016; Mpisane, 2015; Naicker, Chikoko & Mthiyane, 2013; Bambi, 2012). The studies concur that the core duty of HODs should be to spearhead supervision of teaching and learning in schools. Ali and Botha (2006) carried out a study in the Gauteng province of South Africa in which they focused on determining the role of the HODs, their effectiveness, and their importance in contributing to school improvement. Their key finding was that HODs play a key role in the improvement of teaching and learning in schools. They observed that due to the Outcomes-Based Education (OBE), the responsibility of instructional leaders has shifted towards achieving high quality outcomes. They noted that in order to significantly improve teaching and learning in schools, HODs need to spend more time in supervising the teaching and learning activities that take place on a daily basis in their departments. They went on to recommend that HODs should receive professional training according to their observed needs in order to make them more effective. Their study, however, did not investigate how HODs were appointed into their posts or the different approaches used by HODs to ensure the effective implementation of different syllabi, an area which this study interrogated.

Mpisane's (2015) study, conducted in two high schools located in the Ugu district, KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa, asserted that HODs, being middle managers in schools, have a significant role to play in the improvement of teaching and learning through supervision and control. Proper time- management is necessary in order for them to execute this duty effectively. Although the study agreed with scholars who have declared that instructional leadership should be driven by HODs since they play a key role which determines whether teachers teach the learners effectively (Smith et a., 2013; Mestry & Pillay, 2013; Naicker et al., 2013; Bush et al., 2010), it observed that HODs experience challenges in performing this role. HODs encountered challenges in implementing the prescribed goals due to teacher absenteeism and lack of punctuality, managing classwork, and giving feedback, which was attributed to the abnormal workloads that they themselves have. The overcrowded classes also worsen the teachers' predicament by inhibiting the giving of individual attention to learners (Mpisane, 2015). The study also explored the role of high school HODs as leaders of learning. In their role-function as outlined by the Department of Education, HODs supervise teaching and learning, ensuring that class activities are undertaken, and that written work is given, with marking and feedback timeously done. The study established that apart from conducting departmental meetings and assessing teachers' performance, HODs also have their own teaching allocation as well as extra and co-curricular activities. Therefore, HODs would experience challenges in their role as leaders of learning due to their seemingly overwhelming responsibilities (Mpisane, 2015). The study recommended that HODs should introduce mechanisms to closely supervise and monitor class activities, strictly enforce teacher professional discipline, encourage the attendance of workshops and the provision of constructive feedback by teachers during staff meetings, and involve parents of learners in monitoring class attendance.

Malinga (2016) explored practices by HODs of Natural Sciences departments in South Africa in an effort to provide instructional leadership to teachers in a multidisciplinary context. This work reveals that, as middle managers, HODs are under immense pressure because they receive inadequate support from subject advisors and principals, thereby compromising the optimal implementation of the Natural Sciences curriculum. The study concluded that HODs' position as middle managers compromise their instructional leadership capacity.

Tapala's (2019) study used the South African context to investigate the curriculum leadership training programmes of HODs in secondary schools, based on the premise that HODs are an integral part of school leadership. Since their main function is to lead and oversee curriculum support and delivery in schools, HODs are uniquely placed to influence the quality of teaching and learning in their departments as well as within the entire school. The study established that HODs are an important bridge between the school management team (SMT) and the teachers. However, the study highlighted the need for curriculum leadership training for HODs so as to help them to understand what their roles are and how to go about executing those roles so that their influence can be appreciated more.

Jinga's (2016) study in the Gutu district in Zimbabwe explored the policy and regulatory framework that guides instructional leadership, particularly the roles and expectations of the vocational and technical education (VTE) HODs in carrying out their instructional leadership mandate in schools. The findings revealed that there are no uniform criteria for employing HODs in the various schools within the Gutu district. The school heads exclusively made the appointment decisions, sometimes considering or not considering the prospective leader's qualifications, experience and, in the case of church-run schools, church affiliation. The study revealed that the lack of a uniform criteria for appointing the subject leaders sometimes resulted in strained relations between the teachers and their appointed leaders, with negative consequences for subject leadership in the schools. The study also established the need for consistency and improved quality with respect to the enactment of the various practices of instructional leadership by the HODs. The variations in terms of the quantity and quality of supervision practices, particularly the number of lesson observations conducted in each subject or for each teacher, and the guidance activities, including staff meetings to discuss subject-related matters and capacity-building practices, such as the provision of subject-focused professional development opportunities across schools and sometimes within the same VTE department by the HODs, made the practices look arbitrary and rendered them rather ineffective in terms of their potential to influence teachers' knowledge and classroom practices.

Sango, Chikohomero, Saruchera and Nyatanga's (2017) study examined the supervisory strategies being used in the Zimbabwe school system so as to ascertain their appropriateness in guiding teachers in the implementation of the revised curriculum in both the primary and secondary schools. The study established that internal supervision was planned and implemented by school heads, deputy school heads, HODs, and teachers in charge (TIC). The study established that school heads, deputy heads, HODs, and TICs (in the case of primary schools) were overwhelmed with administrative tasks. Many of the school-based supervisors doubled up as administrative officers and full-time class teachers. The study found out that some of the education supervisors did not have sufficient skills for supervising teachers effectively. The study confirmed Chikoko (2009), who noted that school heads did not seem to have sufficient competence to be instructional leaders. The study also found out that there was lack of a collegial relationship between the supervisors and teachers due to the hierarchical relationship that existed between them. It would seem as if teachers were seen as subordinates to be instructed, and not as colleagues to be mentored, encouraged, and motivated. Instructional leadership is described as an influential relationship that motivates, enables, and supports teachers' efforts to learn and change their instructional practices (Mestry & Pillay, 2013). The study further revealed that the most critical resource that seemed to affect supervision in Zimbabwean schools seemed to be time for supervision, as it was so limited that supervision programmes developed by both school-based, close-to-school, and external supervisors rarely saw the light of day. Instead, routine rounds to schools and classrooms for quick "dip-stick" assessments and recommendations seemed to be the norm. Sango et al.'s (2017) study then recommended that the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education initiates capacity building programmes that focus on retooling school leaders with collegial leadership techniques and teachers with professional teacher collaboration etiquette.

Most of the literature reviewed above show that capacity and managerial competency are the standard criteria when selecting HODs (Rorrer, Skrla, & Scheurich, 2008; Kotur & Anbazhagan, 2014). Scholars also place emphasis on the appointees' competencies in the organisation and management of the subject matter (Hallinger, 2012). Aguele, Idialu and Aluede (2008) assert that when appointing HODs, only those teachers who have demonstrated outstanding performance, not only impressive examinations pass rates, and have also shown leadership competences, should be accorded the opportunities to lead in the departments. The core business of a school's existence is to strive for the improvement of teaching and learning (Hallinger, 2012) so this should be given primacy in the appointment of HODs. Bush (2008) asserts that HODs are the defacto instructional leaders in the schools since school heads and other senior staff members are usually occupied with other managerial commitments.

The limited literature about the role of HODs in the supervision of curriculum implementation in Zimbabwe in general and on History teaching and learning in particular indicates that there is a dearth of research on the role of HODs in the school instructional leadership hierarchy. The limited research done on HODs' supervision of teaching and learning in Zimbabwe's education system and elsewhere within the region either explored issues involving VTE subjects (Jinga, 2016; Rajoo, 2012) and natural sciences (Malinga, 2016; Jaca, 2013) or examined their role in instructional supervision within schools in general (Tapala, 2019; Sango et al.,2017; Mpisane, 2015; Ali & Botha, 2006). The instructional leadership role of HODs in marginalised subjects like History has apparently been overlooked, perhaps due to contestations over the utilitarian value of the subject (Sengai, 2019). This study therefore attempts to address this disparity.

Theoretical framework

This study was guided by the instructional leadership theory. Instructional leadership is defined by the leader's skills and knowledge with regard to curriculum, instruction, and academic improvement, or rather, by his/her ability to serve as a leader for instruction (Grissom et al., 2013). Within this definition, strong instructional leaders possess the skills to be hands-on leaders and are involved in the classroom through observing and interacting with teachers, and they are visible within the school and its classrooms (Horng & Loeb, 2010). Instructional leadership is the dynamic delivery of the curriculum in the classroom through strategies based on reflection, assessment, and evaluation, to ensure optimum learning (Cordeiro & Cunningham 2013). This shows that instructional leadership has to commence in the classroom with the teacher being supported by the HOD and other line supervisors up to the school head. Instructional leadership involves sharing a vision with followers, monitoring the instruction and assessment standards, allocating resources, and reflecting on the outcome of the instruction (Lai & Cheung, 2013). The instructional leader is better able to strive for excellence in education by working with teachers, parents, and even the community as a whole, to redefine educational objectives and set school-wide or district-wide goals for improvement (Thaba-Nkadimene, 2016). The understanding of instructional leadership that this paper adopts is one that is inclusive of the curriculum leadership duties and the responsibilities performed by the teacher in the classroom, the HODs, as well as the school head, and the other members of administration. Instructional leadership should therefore embrace leadership actions that facilitate the totality of instruction together with teacher and student learning (Grissom et al., 2013). The term 'instructional leadership' therefore describes a focus on instructional improvement with the ultimate goal being the improvement of learner outcomes (Thaba-Nkadimene, 2016). DeVita, Colvin, Darling-Hammond and Haycock (2007: 8) observe that instructional leadership has recently emerged as "a bridge to school reform", with the ability to link further reform strategies. This appears to call for the metamorphosis of curriculum leadership to be more acceptable to the instructional leaders and their subordinates.

The duty of transforming schools is too intricate to expect one person to achieve without help since the principle of a superhuman leader is now obsolete (Lashway, 2006). In Zimbabwe, school heads delegate responsibilities to their deputies, senior teachers, HODs, and teacher leaders (Jinga, 2016). Leadership therefore involves the collective efforts of several individuals and takes place through a well-designed web of staff relations and interactions. Leadership is no longer perceived as gravitating around an individual, but as a shared responsibility (Cordeiro & Cunningham 2013; Lashway, 2006). This study explored how HODs are apparently accorded the leeway to effectively contribute to the improvement of school-based instructional leadership practices in the implementation of History syllabi at selected schools. The study was particularly interested in how HODs encourage creativity and innovation among teachers so as to boost morale and efficiency, especially in the teaching and learning of History.

Research methodology

In this qualitative study, purposive sampling was used to select the participants. Since the correct numbers of participants in a qualitative study are not rigidly fixed (Gay, Mills & Airasian, 2011), the researcher solicited information from fifteen interviewees. The interview questions in this study interrogated the appointment of HODs, the perceived roles and responsibilities of History HODs, the regularity of the HODs' supervision of the History teachers, and the policies and parameters which delimit their instructional leadership practices. Five school heads, five History HODs and five History subject teachers from five secondary schools out of the thirteen that make up the Glen View/ Mufakose district in Harare Metropolitan province, were interviewed. The interviews were conducted at the respondents' workplaces and ranged between 60 and90 minutes. The respondents were advised in advance about their right to stop the interview whenever they felt that it was not in their best interests to continue (Cohen, Manion & Morrison, 2013). All interviews were held either during lunch or after work to avoid disturbing the work routines of the respondents. Through probing, the researcher ended up with a 'thick' description of the research findings (Denzin, 2011). Data from the interviews were divided into sub-themes to help address the research questions. Being a qualitative study, the research findings may not be generalised (Chawla & Sondhi, 2014), but would rather deepen understanding of HODs' instructional leadership practices in the implementation of the History curriculum.

Document analysis also assisted to explore the instructional leadership practices, the assigning of duties to the key players and the policies that guide the implementation of their duties and responsibilities. Briggs, Coleman and Morrison (2014:297) highlight that, "Documents such as education policy regulations and legislation can provide another level of public narration and insight into how organizations and institutions work, and what values and practices guide decision making". The researcher managed to access some key policy documents in the form of ministerial circulars and minutes of meetings which were kept in departmental files at all the five secondary schools.

The researcher sought informed consent from participants, which facilitated voluntary participation, especially during interviews. In order to protect the identities of participants in this study numerical numbers are used as pseudonyms so that data may not be matched with any participant (Chawla & Sondhi, 2014). The names of five of Zimbabwe's liberation war heroes were also used as pseudonyms for each of the sampled five secondary schools so as to protect the reputation (Cohen et al., 2013) of the teachers, HODs, school heads and the schools. Before the participants signed the consent forms, the researchers assured them of the confidentiality of the data that they would provide.

Findings

The data presented in this section deal with the appointment of History HODs, their perceived roles and responsibilities, the regularity of their supervision of the History teachers, as well as the different approaches they employ to ensure the effective implementation of different syllabi.

Appointment of History HODs

Evidence suggests that HODs are key players in the running of successful departments and schools (Tapala, 2019; Jinga, 2016; Malinga & Jita, 2016; Manaseh, 2016; Mpisane, 2015; Naicker et al., 2013; Bambi, 2012). In view of their pivotal instructional leadership role, the appointment of HODs is carefully planned and follows clear guidelines so as to recruit the most suitable professionals. Consequently, the researcher sought the perspectives of the school heads, History teachers and the HODs themselves on the appointment of History HODs. According to the Provincial Director's Vacancy Announcement Minute No. 1 of 2011: Head of Departments: Harare Metropolitan Province, applicants are supposed to meet the following criteria:

• Be a senior teacher in possession of a Diploma/ Certificate in Education with at least five years' experience.

• Be a certificated graduate in the relevant subject for A' level schools.

• Demonstrate ability to recommend, implement, and monitor policies/systems and procedures in dealing with relevant academic issues.

• Have an organisational ability and commitment to provide leadership in both academic and administrative issues.

• Be capable of working with the public pleasantly, for the achievement of the school's vision and departmental, school and ministry's mission.

• Be mature, committed and hardworking.

• Be able to lead by example.

The involvement of the office of the Provincial Education Director (PED) in the appointment of History HODs in schools in the province bears testimony to the importance of HODs as instructional leaders in schools. Nonetheless, despite the strong recommendations for higher qualifications, these do not always transform into capacity (Jinga, 2016). Evidence in this study suggests that factors other than qualifications were often considered in appointing HODs for the History departments in the five secondary schools in the Glen View/ Mufakose district that were sampled for this study.

At Tongogara High School, the History HOD's (HOD 1) appointment by the school head seems to have been based on hard work and commitment to duty. When asked about how he was appointed, the incumbent (HOD 1) opined:

"When I arrived at this school three years ago, History was among the most unpopular subjects due to the low pass rate associated with the subject at 'O' level. I then worked tirelessly in my first two years and the results for the pupils I taught were very impressive. That is why you see me today as the HOD, despite the presence of very senior staff members in the department."

The interview above clearly shows that the appointment of HOD 1 was based on a good track record in his instructional performance. Interestingly, the school head of Tongogara High School (H 1) was guided by the competences laid down by the provincial circular, as hard work is one of the key expectations in appointing HODs. This was confirmed by the school head (H 1):

"This man completely led a turnaround in History from being one of the most unpopular subjects to one of the most popular in the school so Ifelt obliged to elevate him."

At neighbouring Chitepo High School, HOD 2 confidently asserted that his appointment was based on seniority since he was the most experienced teacher in the History department and even in the school:

"I have been in the teaching profession for the past thirty-eight years so I strongly believe that the head appointed me due to my experience. I am actually more experienced than the head and when she was appointed to this school I actually informally inducted her."

Probed on how he thought his experience would benefit History teachers and learners in the school, HOD 2 expressed the following:

"Having taught History for such a long period of time, I actually know the strengths and weaknesses of different methods of teaching and can choose what to give to my pupils as well as which stuff to leave out. I also know how best to motivate staff in the department. Above all, I am really passionate about the subject and I strive to teach it well."

Again, the appointment of HOD 2 was procedural since seniority is a key requirement for appointments in government departments. The responses by both HOD 1 and HOD 2 reflect a selection process where the school head is the final authority in the appointment of HODs (Kotur & Anbazhagan, 2014; Ling, 2014). This was confirmed by the Head of Chitepo High (H 2):

"Normally I consult other senior staff members for recommendations before making the final decision on who to appoint as an HOD."

When asked about the criteria used to appoint him, HOD 3 at J.M. Nkomo High School stated:

"As a very senior staff member at this school I actually applied for this post when HOD posts were officially announced by the PED through a circular and the Head strongly recommended me. I also hold a Master's degree in History."

The appointment of HOD 3 appeared to be above board as confirmed by his school head (H 3):

"HOD 3 is among the very few substantive HODs in this district. As a school, we are really privileged to have a senior, highly qualified and competent professional like him. He is the current chair of the History Association at district level and has demonstrated his selfless commitment to duty through the assistance he renders both to other History teachers and pupils in the whole district."

It is clear, according to the above interview that the school head knew the best attributes of his staff members, so he recommended the best candidate for appointment to the post of History HOD. This is shown by the way in which he speaks positively about his HOD. The data shows that such appointments are very instrumental in facilitating effective instructional practices in the subject since the best candidates strive to maintain higher instructional standards in the subject. Such appointments are also supported by the rest of the teachers who then do everything possible to improve instructional practices in their subject, thereby immensely benefitting learners. This fits well into the thrust where teachers are expected to lead in areas that match their strengths and are aligned with the school vision (Harris & DeFlaminis, 2016).

The situation at Mazorodze High School was a bit different from the other four schools used in this study, since the History HOD was appointed on affirmative policy grounds. This was revealed by the incumbent (HOD 4):

"When I asked the school head why he settled for me in particular, he clearly explained that it was now national policy to empower women by uplifting those with the requisite qualifications into positions of authority in government institutions. He went on to highlight my sound professional attributes such as seniority, hard work and high academic qualifications. This left me really convinced that despite the presence of equally qualified male staff members in the department, I also merited the appointment."

The above scenario demonstrates the integral role played by government policies in the appointment of instructional leaders in schools. Interestingly, there is a deliberate effort to only appoint those candidates who meet the competence and skills stipulated in the Provincial Director's Vacancy Announcement Minute No. 1 of 2011. However, the affirmative policy has a bearing on the fact that where several candidates possess the same credentials, the advantage will be given to a woman among them. According to one teacher (T 1):

"It really makes no difference to have a woman or a man as HOD in History since the thrust is on professionalism. Women are actually better HODs due to their patience with other staff members and they work equally hard for the betterment of the subject."

The above shows that contrary to some negative perceptions about the competence of women as History HODs, they are also considered as ideal candidates for such posts.

From the empirical evidence above, there are basically four criteria in the selection and appointment of HODs in Zimbabwe. These include work experience, qualifications, outstanding professional attributes, and hard work. In all the five participating schools there is some consistency in the consideration of the four characteristics by the school heads. Although the issues were considered in all the five schools, the importance given to each of them varied from one school to the other.

History HODs' instructional leadership practices

Evidence from this study also revealed that History HODs make use of several instructional leadership practices in order for them to be effective in their supervision duties in their departments. They made use of ministerial guidelines on weekly work coverage, lesson observations and book inspection, team teaching, encouraging, and facilitating the training of History teachers as examiners, participation in subject panels and involvement in the Better Schools Programme in Zimbabwe (BSPZ) activities.

Implementation of the guidelines on weekly work coverage

The respondents all pointed out that the instructional leadership practices of History HODs were guided by the ministerial guidelines on the amount of written work to periodically be given to learners. In 2006, the Ministry of Education released the Director's Circular No. 36 of 2006. This followed countrywide school inspection reports which indicated that generally, the amount of written work administered by teachers to their classes was inadequate. The purpose of the circular was to lay out the minimum expectations for written work in different subjects. Most school heads delegated the HODs to be the key instructional leaders tasked with implementing the ministerial guidelines. According to a school head (H 4):

"The circular provided teachers with the minimum expectations which could be exceeded whenever it is found that the situation on the ground warrants increased pupil activity. The circular reminded teachers to supervise all written work by pupils and such work include class exercises, notes given to pupils by the teacher, notes made by the pupils, tests and assignments as well as diagrams, maps and projects."

History teachers were encouraged to prepare thoroughly for lessons and to use

"charts, pictures, and objects within their school environment, literature from periodicals, magazines, newspapers, drama, songs and external resource persons in order to make lessons more vivid and interesting" (Director's Circular No. 36 of2006:1).

Educational trips to relevant historical monuments like Great Zimbabwe and places with rock and cave paintings were also recommended. The circular stipulated the minimum work requirements in History for both junior and senior secondary school pupils as one objective type of written work per week and one essay type question after every two weeks. These minimum requirements could however be exceeded by teachers, and this was one characteristic of an outstanding History teacher. The instructional supervision duties of History HODs meant checking for the syllabus implementation activities of History teachers through lesson observation and book inspection. The duty of the History HODs therefore involved the supervision of the extent to which the History teachers were following the ministerial guidelines on weekly work coverage. One HOD (HOD 3) supported these requirements:

"The circular made our work quite easy as HODs since it clearly stipulated the minimum requirements of written work for History and other subjects. My duty as the HOD was to simply follow up and ensure that the teachers in my department were sticking to the work requirements stipulated in the circular."

However, HOD 5 reserved the right to differ:

"The problem with some ministerial pronouncements is that they are one-size-fits-all policies which hardly consider the situation on the ground. Some schools have very large classes and teachers are really strained to the limit. The ministerial stipulation for the teacher-pupil ratio is 1:35 but most classes go up to between 50 and 60 pupils. To expect a teacher to frequently give written work to such large classes and mark effectively every week is rather unfair."

The excerpt above shows the lack of harmony between national instructional leadership expectations and the situation on the ground during implementation since History HODs appear to be facing non-conformity challenges from teachers due to their large classes. Due to their proximity to the classroom, instructional leaders like HOD 5 are more pragmatic to the extent of sympathizing with the teachers' arduous work requirements.

Lesson observations and book inspection

History HODs were identified as the ones to who school heads mostly delegate the supervision of History teachers in the schools involved in this study. The HODs conduct lesson observations and document inspection of schemes of work, record of marks and learners' exercise books for the teachers in their departments to try to maintain high instructional standards. In all the five schools sampled for this study, the History HODs checked schemes of work at the beginning of each term and subsequently on a weekly basis for updates and timely evaluation by the teachers. In four schools, the History HODs inspected learners' exercise books once every month while in one school the HOD inspected them twice per term. Detailed reports were supposed to be produced by each History HOD after the lesson supervision visits and exercise books inspection. The History HODs in all the five schools consistently carried out brief post lesson observation conferences with teachers where they discussed the key aspects of the lessons observed. Such aspects include the appropriateness of the methods used during the lessons, the extent of teacher to pupil and learner to learner interaction as well as the extent to which the objectives were achieved. The comprehensive narrative reports produced after such exercises were an oasis of motivation for most teachers as they highlighted the teachers' strengths and weaknesses as well as recommendations on how to improve. A History teacher (T 4) remarked that:

"Our HOD is a very good motivator because every time when he observes me teaching, his main thrust is to emphasize on my strengths before merely 'flyingpast' my weaknesses. To me, this has been a source of motivation and I always keep his assessment reports neatly in my file as souvenirs. This is because his comments are not damaging but encouraging while the recommendations are more of suggestions on how to deliver effective lessons."

In the same vein, this study discovered that lesson observations, book inspections, and other related activities by the History HODs greatly facilitate the passing on of good practices to junior teachers by the History HODs, thereby professionally developing them. This is done through the comprehensive narrative reports written by the History HODs which they then sit down and discuss with the teachers during the post-observation interviews. The aspects that they pay attention to during supervision include teaching strategies, classroom management, questioning techniques, learner participation, teacher to learner and learner to learner interaction, use of the chalkboard and other teaching media, teacher's comments, homework for learners, achievement of the lesson obj ectives, subj ect mastery by the teacher and general professional attributes. Interestingly, it emerged that during scheduled lesson visits by the administrators at their schools, the majority of History teachers interviewed prefer to be observed by their HODs rather than others within the school's corridors of power. A History teacher (T 5) claimed that:

"Our school occasionally arranges lesson visits by members of the administration including HODs. During such visits, I prefer to be observed by my History HOD. When I get a lesson observation from my HOD, it is different from being observed by other administrators who are usually fault-finding and witch-hunting. Since he is a specialist in my subject area, the HOD observes and gives me genuine feedback which I can benefit from especially going forward. On the other hand, when other administrators observe my lessons, their main thrust is normally to expose my weaknesses.:

A school head (H 5) confirmed thus:

"Teachers at my school seem to prefer being observed by their HODs so I respect their opinions since the HODs are subject specialists and they offer spot-on recommendations to teachers."

Most History teachers interviewed during this study demonstrated a passionate dislike of having their shortcomings exposed during lesson observations, book inspections and other forms of supervision by school administrators. Nonetheless, this study found that the identification of teachers' weaknesses during supervision exercises actually forms the basis for staff development programmes within and among schools since the aim of teacher professional development (TPD) programmes then becomes to address the observed weaknesses together with other perceived shortcomings. The History HODs are also encouraged to highlight the observed strengths and weaknesses of their teachers during departmental staff meetings without mentioning any names so that the History teachers become aware of the good methods by their colleagues as well as the bad practices to avoid.

This study found that in order to cultivate cordial working relations, the History HODs conduct pre-observation and post-observation discussions with their teachers. One History teacher (T 2) said:

"Before the class visit, my HOD even asks me about the strategies I want to use in the lesson so that in the post-observation discussion he will frankly tell me whether I used the best methods to deliver the lesson. He is very informative and professional."

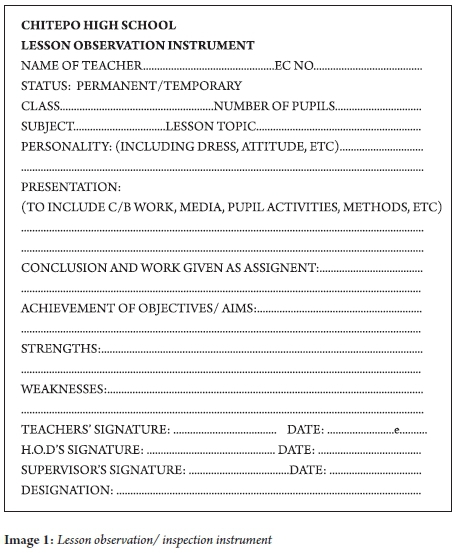

The above interview highlights the importance of good rapport between the HOD and the departmental members. Image 1 below is an exemplar of a lesson observation inspection instrument.

It is important that instructional leaders are experts in their various subjects and that they are able to draft protocols that are subject specific (Jinga, 2016). This is where HODs who are subject specialists become useful. Interestingly, in this study all the five History HODs were highly competent specialists in the subject with at least a first-degree qualification.

Closely related to the lesson observations, the researcher observed that History HODs also carry out routine inspections of exercise books, schemes of work and other records used by the History teachers. During book inspection, the History HODs pay attention to the frequency of written work, marking, comments in learners' exercise books, appropriateness of the written work, scheme evaluation, recording of learners' work, as well as whether the teachers were meeting the ministerial work requirements for the subject. These documents also had their own inspection reports which were written on forms almost similar to the ones used for lesson observations. Image 2 below is an exemplar of a Record of Work Inspection Form.

Team teaching

In all the five schools that took part in the study, History HODs encourage and organize team teaching as a common practice where History teachers at the same school share topics in the same class based on an individual teacher's competence. The HODs actually design roasters which the departmental members follow during team teaching lessons so as to avoid disrupting the school timetables. Team teaching refers to the cooperation between teachers in the same subject in a school in handling certain aspects of their teaching programme by sharing responsibilities (Taruvinga, 1997). For the purpose of achieving positive departmental milestones, teachers need to be able to work together. Spillane (2011) uses the term 'collective leading' to describe a situation where department members collaborate to co-enact particular leadership tasks. This enables teachers to effectively cover most aspects of the syllabus and ensures that learners derive maximum benefits from History lessons. Another form of team teaching discovered during this study is whereby one teacher would teach a lesson while the rest of the departmental teachers were in attendance, contributing to the lesson with comments and additions at the end of the lesson. Team teaching also extended to the collective marking of pupils' written work in the department to reduce the subjectivity by some teachers. During the marking of internal examinations, History teachers at all the five schools practised what was referred to by T 1:

"Different topics were also allocated to teachers based on competence. Even if the class is mine, I can still invite a colleague to come and conduct a lesson on a topic that I may not be comfortable with but which he/she is very good at."

Team teaching appears to be a good way of facilitating staff development among teachers because this encourages the sharing of ideas and resources. Above all, the History teachers admitted that it also facilitates collegiality among teachers, fostering cooperation instead of competition among departmental members. According to HOD 2:

"Team teaching was central in helping History teachers to deal with both the 2166 and 2167 History syllabi since the teachers came together to share experiences and ideas on how to tackle seemingly insurmountable concepts."

According to one History teacher (T 2):

"Team teaching really brought positive results to my pupils since my colleague was able to effectively teach some of the areas I was not so comfortable with."

Another History teacher (T 4) also strongly supported team teaching thus:

"Since variety is the spice of life, it is always refreshingfor pupils to hear a different voice in their History lessons so we regularly do team teaching at our school."

All the History teachers interviewed in this study unanimously agreed that their HODs took the initiative in encouraging team teaching within their departments.

Training of History teachers as examiners

History HODs also encourage their teachers to be trained as examiners in national examinations. This is spearheaded by the national examinations body, the Zimbabwe School Examinations Council (Zimsec), which offers History teachers contracts to mark public examinations during school holidays. History HODs play a crucial role in the training of their colleagues as examiners since the History teachers' applications are considered on the basis of the recommendations from their HODs. According to one History teacher (T 3):

"Our HOD encourages us to train as History examiners at national level. Training and performing the duties of public examiners helps us in preparing our learners for the gruelling public examinations especially on issues to do with difficult aspects or questions such as part (c) of the History 2167 Syllabus Ordinary Level Papers."

Teachers also appear to derive motivation and self-actualization due to their added status in the subject once they become public examiners. This came out clearly during the interviews. Another teacher (T 5) said:

"Obviously when one becomes an examiner there are some benefits that come with the responsibility. Apart from the monetary benefits, one also begins to feel more confident in the execution of duties. Other teachers also begin to look up to you with respect and expect some guidance in issues to do with teaching and preparation of learners for public examinations."

The above sentiments show that such teachers are key sites of instructional leadership since they become leaders in their own right, especially through the assistance they render to other teachers and the cascading of critical information regarding the teaching of the subject. History HODs play pivotal leadership roles in staff development since they recommend teachers to attend training as examiners. These teachers in turn train other teachers, albeit informally, thereby contributing to better instructional practices.

The role of History subject panels

History HODs also work in collaboration with subject panels where History teachers meet periodically to discuss emerging trends in the subject. According to the Director's Circular Minute No. 13 of 2008, the appropriateness of the curriculum should be based on the extent to which it meets individual attributes, the economy, and the needs of society. In an effort to ensure that the curriculum is relevant and appropriate, a participatory approach in both planning and implementation is essential. Accordingly, the participatory approach in curriculum development can be effective through the use of subject panels where HODs are the key participants (Sengai, 2019). The purpose of establishing subject panels is to generate curriculum ideas from a broad spectrum of the teaching fraternity and to achieve national consensus on curriculum goals. Apart from coordinating the subject panels, History HODs also passionately encourage the participation of teachers from their departments in the activities of these key staff development forums.

The Curriculum Development Unit (CDU), which is a centralised curriculum development organ in the country, was tasked to carry out most of its activities through National Subject Panels (NSP). A History teacher (T1) explained thus:

"At subject panels, under the leadership of our History HODs, we usually discuss marking schemes for examination questions, teaching methods as well as the challenging topics where most of our pupils perform poorly in national examinations. The HODs sometimes invite resource persons to come and facilitate at subject panels."

The challenges that merit consideration at such forums include topics that prove to be challenging for most History teachers, teaching methods/strategies, the minimum expectations of written work in the subject, sharing techniques on dealing with problematic History topics such as controversial issues, and challenging examination questions like source-based questions and how best to prepare for public examinations. This was supported by another teacher (T 4), thus:

"History subject panels help us as History teachers to congregate and then share ideas on how best to teach our subject and also prepare for national examinations."

On a brighter note, the History HODs are also exposed to new knowledge during subject panel meetings which they pass on to teachers in their departments through the cascading model of staff development. According to T 5, the HOD helped to unpack seemingly challenging syllabi such as History 2166, which appeared to present the teachers with seemingly insurmountable problems due to their lack of the abstract skills needed during the interpretation of sources:

"After attending History subject panel meetings, the HOD took his time to staff develop all History teachers in the department on how to interpret the syllabus. The HOD helped teachers in interpreting the sources or pictures to the learners as well as other key skills covered by the syllabus such as empathy, imagination, judgement and analysis."

This shows that the HOD was actually professionally developing History teachers in his department. Some History teachers ended up developing keen interest in the 2166 History syllabus due to the assistance that they got from their HOD. All the other History teachers at the school also benefitted because they got help from the HOD, who particularly helped the teachers in tackling the questions on empathy and imagination. The History teachers ended up appreciating that the History 2166 syllabus was very rich, both in terms of content and the skills it emphasized. T 5 added that:

"Due to the tireless efforts by our HOD who went out of her way to try and help teachers in her department, we ended up appreciating the strengths and possibilities in the 2166 History syllabus. That syllabus was very rich and it produced fully-baked products. The 2166 History syllabus was blessed with a wide range of skills which helped to mould the History learner into a socially useful individual."

The Better Schools Programme in Zimbabwe (BSPZ) activities

In its pursuit of improved instructional practices, the BSPZ, through the involvement of school-based instructional leaders, introduced the setting of district examinations for all subjects at secondary school level. In the case of History, these examinations are actually set by HODs and other senior History examiners in the district and are written under strict observation of public examination regulations by all schools in a district. Marking schemes for such examinations are also designed by the History HODs and senior examiners in the district. According to a History teacher (T 2):

"Under the leadership of their HODs, History teachers in the district then gather to discuss and moderate the marking schemes. Examiners in the district are placed in charge of the moderation of marking schemes so as to avoid wide deviations between the markers. After marking the examinations, the best three scripts per school are forwarded to the district for moderation."

BSPZ also introduced monetary awards for both the outstanding History student and the History teacher with the best overall results in the district. After these examinations, the district sometimes convenes a congress to discuss topical issues and difficult topics identified by History teachers and also reflect on pupils' performance in the examinations. The leading district's History HODs and examiners are then invited to facilitate discussions at seminars, thereby benefiting both teachers and pupils. Interestingly, the BSPZ works closely with the History Subject Panels and HODs in all their activities so as to improve school-based instructional leadership practices. The institutionalisation ofdistrict to school-based instructional leadership practices is, however, hampered by challenges associated with running public examinations at district level, such as the shortage of resources coupled with the absence of History subject Education Officers (EO) to spearhead and coordinate the processes.

Discussion

The key finding from this study is that the HODs were the defacto school-based instructional leaders (Bush, 2008), overseeing the implementation of the History syllabi. Their degree of involvement determines the success and/or failure of different syllabi (Tapala, 2019; Mpisane, 2015; Bambi, 2012). School heads normally delegate the supervision of History teachers to the HODs who then carry out lesson observations and document inspection on the teachers in their departments so as to try and maintain high instructional standards. Four out of the five History HODs interviewed in this study unanimously felt that the delegation of instructional leadership and managerial duties to them was actually a way of grooming them for higher administrative posts in the school system since their competence would have been tested and proven. While the fifth HOD in the study did not have ambitions to assume an administrative post in future, she still felt that the assigning of extra managerial duties to her by the school head was procedural since it was part of her job description.

Secondly, the assigning of instructional leadership responsibilities by school heads, as established in this study, has led to the empowerment of History HODs to actively become involved in school-based instructional leadership for their subject. The practice is not just about the actions of individual leaders, but is fundamentally about interactions (Spillane, 2011). This study established that school heads have empowered History HODs to act as their foot soldiers in terms of routine supervision of teachers in classroom activities. This has the positive consequence of spurring History teachers to work harder since HODs are subject specialists who, in most cases, command genuine respect among the teachers (Mpisane, 2015).

Thirdly, this study established that the more rigorous the TPD programmes, the better the improvement in instructional practices in the subject. Since they are in charge of all the academic programmes in their departments, History HODs usually take the opportunity to attend workshops, subject panel meetings, as well as other staff development programmes to represent their departments. This study established that such duties actually give the HODs a chance to be trained in various aspects to do with the subject, thereby empowering them to deal with issues in their subject from an informed position. Resultantly, HODs become very effective in ensuring high quality instructional practices within their schools through the cascading of the issues to their departmental colleagues during departmental staff meetings (Tapala, 2019).

The focal point of HODs should be to assist teachers to engage in activities that have an effect on learners' growth, hence the need for teachers to be developed professionally to ensure effective teaching and learning of the subject (Tapala, 2019). This is what happened during the implementation of the History 2167 syllabus, thereby leading to its success (Sengai & Mokhele, 2021). The most influential instructional leadership practice at school level is promoting teachers' professional development (Blasé & Blasé, 2004). Instructional leadership should not be concerned with teaching and learning only but should also include the TPD which ultimately results in students' growth. Schools should therefore look for opportunities to increase the professional development and job performance of teachers, hence the need to explore the guidance and support teachers are given to enable this development (Tapala, 2019). However, Zimbabwe like most developing countries, has generally failed to demonstrate sufficient enthusiasm towards the establishment of TPD programmes at national level due to the government's failure to generously fund such initiatives (Sengai & Mokhele, 2021). Despite the challenges, TPD is a key facilitator of the school-based instructional leadership practices, especially for the marginalised subjects like History (Sengai & Mokhele, 2020).

Lastly, this study also established that whilst the school heads set targets for the whole school, departmental goals and targets are set by the HODs in concurrence with the subject teachers. Due to the proximity between the HODs and their teachers in terms of instructional leadership, it becomes easier for them to interact more often in the implementation of the History curriculum. The interpretation of the general school or district targets into workable plans for the History subject teachers is thus the critical ingredient for effective leadership of the subject.

Conclusions and recommendations

This study concluded that it is the duty of History HODs to ensure that the subject is taught properly in the schools. This can in turn yield the implementation of rigorous instructional leadership programmes so as to facilitate improvement in instructional practices in the History classroom. Such instructional practices lead to improved performance by pupils in the subject, both in local and external examinations (Sengai & Mokhele, 2021). History HODs, as instructional leaders, are expected to play a key role in the restoration of the culture of teaching and learning. In light of their increasing administrative and managerial responsibilities in schools, school heads can no longer afford to be seen at the chalk face of instructional leadership (Hayward, 2008). HODs are expected to be the piston in the instructional leadership engine in schools. Their instructional leadership roles need to be grounded in their knowledge and skills, and not simply their prestigious position (Dean, 2002). Being subject and pedagogical experts should be a perennial source of confidence and motivation for HODs. Competent HODs may need the authority and autonomy to 'run with the ball' (Mercer, Barker & Bird, 2010). However, this could be another topic for further research.

The study therefore recommends that instructional leadership practices be more effective and stricter, but friendly at the same time, so as to cultivate respect and trust among the supervisors and supervisees in the subject. The study further recommends increased opportunities for more teacher involvement in TPD roles so as to enhance their participation in curriculum issues at school level, at the district and provincial levels as well as nationally. It is also recommended that the teaching loads of History HODs be further reduced in order for them to be more effective in their instructional leadership roles as well as in the occasional administrative duties delegated to them by their school heads. The study also recommends the setting up of a BSPZ national coordinator for History to spearhead TPD programmes at the highest level which can be cascaded down to the schools. This will facilitate the improvement of school-based instructional leadership practices since the position should ideally be held by a former History HOD with hands on experience of the challenges and possibilities associated with instructional leadership of the subject starting at grassroots level.

References

Aguele, LI, Idialu, EE and Aluede, O 2008. Women's education in Science Technology and Mathematics (STM) challenges for national development. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 35(2):120-126. [ Links ]

Ali, F & Botha, N 2006. Evaluating the role, importance and effectiveness of heads of department in contributing to school improvement in public secondary schools in Gauteng. MGSLG, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Bambi, A 2012. The role of Heads of Departments as instructional leaders in secondary schools: Implications for teaching and learning. Unpublished Doctoral dissertation. Johannesburg: University ofJohannesburg. [ Links ]

Blasé, J & Blasé, J 2004. Handbook of instructional leadership. How successful principals promote teaching and learning. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Briggs, ARJ, Coleman, M & Morrison, M 2012. Research Methods in Educational Leadership & Management. SAGE, Los Angeles. [ Links ]

Bush, T 2008. Leadership and management development in education. Sage. [ Links ]

Bush, T, Joubert, R, Kiggundu, E & Van Rooyen, J 2010. Managing teaching and learning in South African schools. International Journal of Educational Development, 30(2):162- 168. [ Links ]

Chawla, D & Sondhi, N 2014. Research Methodology Concepts and Cases. New Delhi: Vikas Publishing House Pvt Ltd. [ Links ]

Chikoko, V 2009. Educational decentralisation in Zimbabwe and Malawi: A study of decisional location and process. International Journal of Educational Development, 29(3):201-211. [ Links ]

Cohen, L, Manion, L & Morrison, K 2013. Research methods in education. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Cordeiro, PA & Cunningham, WG 2013. Educational Leadership: A Bridge to Improve Practice. Boston: Pearson. [ Links ]

Dean, J 2002. Implementing performance management: A handbook for schools. London: Routledge Falmer. [ Links ]

Denzin, NK 2011. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research. New York: SAGE. [ Links ]

DeVita, MC, Colvin, RL, Darling-Hammond, L & Haycock, K 2007. A bridge to school reform. New York, NY: The Wallace Foundation. [ Links ]

Director's Circular No. 36 of 2006. Guidelines on Weekly Work Coverage in Primary and Secondary Schools. Harare: Ministry of Education Sport and Culture. [ Links ]

Everard, KB, Morris, G & Wilson, I 2004. Effective school management. New York: Sage. [ Links ]

Gay, LR, Mills, GE & Airasian, PW 2011.Educational research: Competencies for analysis and applications. London: Pearson Higher Ed. [ Links ]

Jinga, N 2016. Instructional Leaders for Vocational and Technical Education: Case Studies of Selected Secondary Schools in the Gutu District of Zimbabwe. Unpublished PhD Thesis. Bloemfontein: University of the Free State. [ Links ]

Grissom, JA, Loeb, S & Master, B 2013. Effective instructional time use for school leaders: Longitudinal evidence from observations of principals. Educational Researcher, 42(8):433-444. [ Links ]

Hallinger, P (2012). A data-driven approach to assess and develop instructional leadership with the PIMRS. In Shen, J (ed.) Tools for improving principals' work, pp. 47-69. New York: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Harris, A & DeFlaminis, J 2016. Distributed leadership in practice: Evidence, misconceptions and possibilities. Management in Education, 30(4):141-146. [ Links ]

Hayward, R 2008. Making quality education happen: A 'how-to' guide for every teacher. Johannesburg: Caxton. [ Links ]

Horng, E & Loeb, S 2010. New thinking about instructional leadership. Phi Delta Kappan, 92(3):66-69. [ Links ]

Kotur, BR & Anbazhagan, S 2014. The influence of age and gender on the leadership styles. Journal of Business and Management, 16(1):30-36. [ Links ]

Lai, E & Cheung, D 2013. Implementing a new senior secondary curriculum in Hong Kong: Instructional leadership practices and qualities of school principals. School Leadership & Management, 33(4):322-353. [ Links ]

Lashway, L 2006. The landscape of school leadership. School leadership: Handbook for excellence in student learning, pp.18-27. [ Links ]

Ling, TW 2014. An Examination of School Principals' Moral Reasoning and Decision- making along the Principalship Track and Across Years of Experience. Doctoral dissertation. Florida: University of Central Florida. [ Links ]

Malinga, CB 2016. Middle management and instructional leadership: a case study of Natural Sciences' Heads of Department in the Gauteng Province, Unpublished PhD Thesis. Bloemfontein: University of the Free State. [ Links ]

Manaseh, AM 2016. Instructional leadership: The role of heads of schools in managing the instructional programme. International Journal of Educational Leadership and Management, 4(1):30-47. [ Links ]

Mercer, J, Barker, B & Bird, R 2010. Human resource management in education: Contexts, themes and impact. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Mestry, R & Pillay, J 2013. Editorial, Education as Change, 17:(sup1): S1- S3. [ Links ]

Moreeng, B & Tshalane, M 2014. Transformative curriculum leadership for rural ecologies. Bloemfontein: University of the Free State, Faculty of Education. [ Links ]

Mpisane, BB 2015. The role of high school heads of department as leaders of learning. Unpublished Doctoral dissertation. Durban: University of KwaZulu Natal. [ Links ]

Naicker, I, Chikoko, V & Mthiyane, SE 2013. Instructional leadership practices in challenging school contexts. Education as Change, 17(sup1):S137-S150. [ Links ]

Provincial Education Director's Vacancy Announcement Minute No. 1 of 2011: Heads of Department: Harare Metropolitan Province. Harare: Ministry of Education, Sport, Arts and Culture Harare Provincial Office. [ Links ]

Rajoo T 2012. An investigation into the role of the Head of Department (HoD) as an instructional leader in the leadership and management of the teaching and learning of Accounting in two secondary schools in one district in Gauteng. Unpublished Masters Dissertation. Johannesburg: University of Witwatersrand. [ Links ]

Rorrer, AK, Skrla, L & Scheurich, JJ 2008. Districts as institutional actors in educational reform. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(3):307-357. [ Links ]

Sango, MG, Chikohomero, R, Saruchera, KJ & Nyatanga, EK 2017. Supervision for Quality implementation of School Curriculum blue print: The Case for Manicaland Province -Zimbabwe. International Journal of Case Studies, 6(8):20-26. [ Links ]

Sengai, W 2019. Teachers' perspectives on 2166 and 2167 History curriculum reforms: an explanatory study of Harare province. Unpublished PhD Thesis. Bloemfontein: University of the Free State. [ Links ]

Sengai, W & Mokhele, ML 2020. Teachers' perceptions on development and implementation of History 2167 syllabus in Zimbabwe, Cypriot Journal of Educational Sciences, 16(3):916-927. [ Links ]

Sengai, W & Mokhele, ML 2021. Examining the role of instructional materials in the implementation of history 2166 syllabus in Zimbabwe. African Perspectives of Research in Teaching & Learning 5(1). [ Links ]

Smith, C, Mestry, R & Bambie, A 2013. Roleplayers' experiences and perceptions of heads of departments' instructional leadership role in secondary schools. Education as change, 17(sup1):163-176. [ Links ]

Spillane, JP 2011. Distributed Leadership. San Francisco CA: Jossey Bass. [ Links ]

Tapala, TT 2019. Curriculum leadership training programme for heads of departments in secondary schools. Unpublished Doctoral dissertation, North-West University (South Africa). [ Links ]

Taruvinga, CR 1997. The crisis of 'O' Level History in Zimbabwe: A silent but dominant Theory of Knowledge, a didactic practice. Zimbabwe Bulletin of Teacher Education, 5(3):35-47. [ Links ]

Thaba-Nkadimene, KL 2016. 'Improving the management of curriculum implementation in South African public schools through school leadership programme: a pragmatic approach'. South African International Conference on Education. South Africa. [ Links ]