Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Yesterday and Today

On-line version ISSN 2309-9003

Print version ISSN 2223-0386

Y&T n.24 Vanderbijlpark Dec. 2020

HANDS-ON ARTICLES

In the moment of making History: The case of COVID-19 in Zambia

Ackson M Kanduza

Zambian Open University, Lusaka, Zambia. ackson.kanduza@zaou.ac.zm

ABSTRACT

This paper discusses the unfolding of COVID-19 in Zambia between March and August 2020. Zambians were aware that international networks would lead to Zambia being affected by a disease that had caused much devastation in China. The discussion also demonstrates the ambiguous nature of economic means for survival. Thus, the search for means of survival would also become transmission lines of a deadly disease. The state used a mixture of liberal and authoritarian ways to deal with the spreading of the infections. The pandemic revealed the inadequacy of medical facilities. The discussion combined limited oral information, newspapers and published primary sources.

Keywords: COVID-19; Pandemic; Multi-sector; Responses; Collaboration.

Introduction

This article is about responses to COVID-19 in Zambia between March and August 2020 in the context of my deliberately selected backgrounds that inspire intellectual diverse reflections and research pathways. This is a contemporary theme and thus not yet ripe for historians to study and analyse systematically and in considerable depth. Yet the historian's craft can cautiously be used and rationalised in terms of some established precedents and examples by paying attention to the nature of sources and selected research methods. One such precedent will suffice here. George Washington Ochs Oakes started a journal known as Current History in 1914 in New York having been motivated to capture history at the moment of its making1 because of a continuous flow of unique and diverse events that human beings cause or react to. In 1914, the outbreak of what became known as the First World War was seen by some people as deserving immediate, full coverage and accurate recording. Margaret Macmillan, a Canadian and renowned historian of the Commonwealth and the British Empire, analysed how what initially seemed to be an assassination of no significance built into a major and complicated European War.2Comprehensive and reliable recording of data is cardinal for constructing history. These are some of the characteristics that Moses E. Ochonu addressed in his search for sources of historical data that were not elusive, not fractured and not politicised, especially when studying postcolonial African history.3The present engagement deals with contemporary history in Zambia that has distinctive global dimensions. This article discusses aspects of how Zambia managed COVID-19 in the early phase of the pandemic, mainly between March and August 2020. The discussion examines how Zambia reacted to the inevitability that the pandemic would be imported into the country and would later be spread from within the country.

At this preliminary stage of my research, the article is organised around three broad outlines. First, leadership of and mobilisation by the Government of Zambia. Second, a preliminary discussion of the social and economic impact of COVID-19 in Zambia, including diverse ways in which the Zambian population reacted to the news of the pandemic and to the policies implemented by the government. The Zambian population combined scepticism, resistance and compliance to policies on COVID-19. Third, I refer to general and scholarly links to earlier emergencies and pandemics in Zambia. COVID-19 dominated national debates and thus deserves multidisciplinary scholarly scrutiny. COVID-19 is a current and contemporary event and thus my participants' observations and experiences are significant organic sources. Further, using several Zambian newspapers and a few specialist reports, the article primarily deals with some key measures the Government of Zambia formulated and implemented in mobilising people in Zambia in order to minimise deleterious social and economic effects of the pandemic. It should be stressed that the complexity of the pandemic and limited medical resources in Zambia compelled the Government to purposely cultivate and promote voluntary participation of the population in all strategies in order to contain the spread of COVID-19 and in the treatment of those infected.

Government leadership in mobilising and collaborating against COVID-19

On 18 March 2020, Zambia reported the first two infections of COVID-19.4 This was a couple who had been on holiday in France. The couple were quarantined and their contacts within Zambia traced. They were treated and recovered. Four months later, at the end of July, the Ministry of Health reported that the COVID-19 situation had deteriorated and infection had increased from 1 632 infected cases reported on 6 July to 4 481 cases recorded on 26 July 2020.5 Consequently, from early March 2020, COVID-19 emerged as a regular and dominant topic of discussion in all forms of media and on interaction platforms in Zambia. Weekly bulletins by the Minister of Health, Dr Chitalu Chilufya and occasional press conferences by the republican president generated issues for common conversations. The COVID-19 pandemic became a regular front page topic in newspapers and a top news report in television and radio broadcasts.

Discussions took diverse forms. The Government focused on foreign relations and domestic context as key issues in the discussions. Because of Zambia's high economic dependence on China, at a political level and in a Ministerial Statement to the Zambian Parliament on 5 March 2020, the Minister of Health, Dr Chitalu Chilufya, cautioned that Zambia was not going to condemn China on the coronavirus epidemic reported in Wuhan City in Wei Province of China as doing so would be xenophobic.6 In any case, strong, economic and political ties between Zambia and China dated back to the 1960s. Appeals for friendly treatment of China in Zambia predated the COVID-19 outbreak. For example, in September 2018, the seemingly authoritative publication Africa Confidential reported on speculation that China would take over the Zambia National Broadcasting Corporation (ZNBC) if the country failed to pay back some loans.7 Despite such opinions, the Zambian Government pledged to avoid any xenophobic statements against China. This attitude was the main factor in the decision of the government not to evacuate Zambians, especially students, from China at a time that several African countries brought back their citizens. As if in a direct reply to the ministerial statement on 15 March 2020, a contributor to one of my social media platforms observed laconically, "I am preparing for the coronavirus even if I do not have a passport to go to China to get infected". This subtle critique that displayed both helplessness and determination to survive the pandemic was sensitive to the complex ways COVID-19 could and would take root in Zambia. COVID-19 also attracted reflections from Zambian intellectuals. For example, Mutale Tinamou Mazimba Kaunda, a history teacher at Samfya Secondary School in Luapula Province, Zambia, wrote about COVID-19 saying, "All I can say is that it has given me a new appreciation of the Spanish Flu of 1918. I feel like I am seeing the past in the present. Truly, history does repeat itself'.8 Kennedy Chipundu, another history teacher at Samfya Secondary School, asserted that "there was no COVID-19 in Samfya".9 Such diverse views called for pragmatic and flexible mobilisation and ruled out authoritarian actions.

These diverse views complicated which choice of intervention to adopt. Initially, planning and implementation were simultaneous. For example, on 17 March, out of the blue, all educational institutions from pre-school to university were ordered to close immediately.10 The Ministry of Health launched a national strategy that encouraged public compliance with public health measures which were considered effective in avoiding COVID-19 infections.11 The President as leader of Cabinet, Ministry of Health medical personnel and a multisector Cabinet team provided collaborative leadership in mapping directions the population in Zambia needed to take in order to avoid infections such as those reported in China, Europe, the United States of America and other parts of the world. On 25 March, President Edgar Chagwa Lungu outlined measures to deal with COVID-19 as a pandemic with foreign origins.12 The view that COVID-19 was an imported infection received high attention. The response strategy was twofold: first, to contain COVID-19 as a pandemic that originated outside Zambia and, second, to prevent the pandemic from spreading within Zambia. The President announced that with immediate effect, only Kenneth Kaunda International Airport in Lusaka would be used by incoming and departing aeroplanes. Three international airports were closed. These were the Harry Mwaanga Nkumbula International Airport in Livingstone, Mfuwe International Airport in the Luangwa valley in Eastern Province, and Simon Mwansa Kapwepwe Airport in Ndola in Copperbelt Province. In the main, international land borders remained open to avoid a negative impact on the economy in terms of imports and exports. Despite the difficulties of cutting major international links, the decision to restrict air traffic to one airport was relatively easier than deciding on an appropriate ban or restrictions on land borders.

Over time, land entry points were subjected to severe immigration controls and restrictions. It was not easy to restrict entry into Zambia from eight neighbouring states. In his address to the nation on 25 March 2020, President Lungu stated:13

[Government has] 'devised a phased strategy that will take into consideration interventions for the low- and high-income groups, low-and high-density areas, rural and urban areas. It is with this in mind that essential business activity in goods and services will be kept running.

The Government feared extending the ban to eight borders but recognised that decisions of the neighbouring states would inevitably close entry into or exit out of Zambia.14 The Government observed that it would accept the closures of the boundaries which six of eight neighbours of Zambia had imposed. Zambia did not impose a lockdown that banned the population from visiting border towns such as Nakonde. The main reason given was that the low-income sections of the population depended on land-based trade directly and indirectly. In terms of direct trade, there are many Zambian itinerant traders plying their trade between Zambia and some of their neighbours, namely Tanzania, Democratic Republic of the Congo, South Africa, Namibia and Botswana. Indirectly, these low-income sections of Zambian society depend on buying from large South African supermarkets such as Shoprite Checkers, Spar or Pick n Pay. These sectors make up a major part of retail trade in urban Zambia, where probably over 45 per cent of Zambia's population of about 18 million people live. These are sources of diverse commodities, which small-scale entrepreneurs buy for resale in remote urban and rural areas. These entrepreneurs serve communities with poor transport links to the main trading and industrial areas. Nevertheless, the population was called upon to reduce non-essential travel, including that related to itinerant trading.

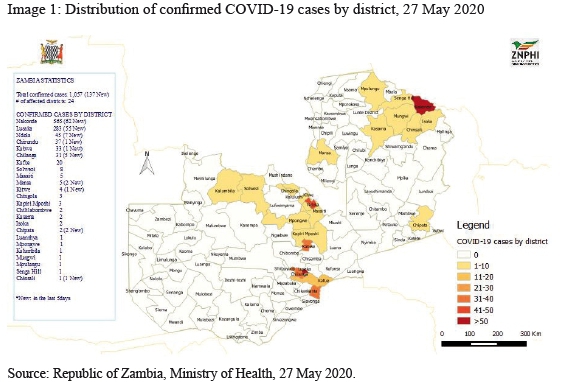

These controls or restrictions were not easy to implement. One of the difficulties was that it was a complex reversal of policy for a government that came to power in 2011 on a policy plank that Zambia was land-linked rather than landlocked. Believing that Zambia would be a hub of economic activity as the central market for what Zambia produced for the nine countries (including Burundi linked via Lake Tanganyika water transportation),15 Zambia avoided a total lockdown. Within the country, there was fear in government circles that a population of 7,6 million people in 43 districts near the borders was at risk of high and rapid infections due to border crossings and their location on major highways and transport corridors. Cross-border trade dominated the economic life of border populations. The collaborative effort of UN agencies in the country, development partners and the Zambian government was about economic difficulties that would affect about 65 per cent of the 18 million Zambians working in the informal sector. Between 45 per cent and 53 per cent of the national population reside in urban areas. Seventy per cent of this urban population resides in informal residential settlements with high population densities and with only inadequate basic services such as water, sanitation and waste management.16 Over the following months, truck drivers entering Zambia through Katima Mulilo from Namibia, Kazungula from Botswana, Livingstone from South Africa, Chirundu from South Africa, Muchinji from Malawi and Mozambique, Nakonde from Tanzania and Kasumbalesa from Democratic Republic of the Congo were tested and quarantined for 14 days. The quarantines, with the main centres shown on the map below, were in designated places such as at the Universities of Zambia and Makeni in Lusaka. These diversions of the trucks stopped distribution of essential products and thus caused commodity shortages in many parts of the country.

The Ministries of Health, Home Affairs, Information (as the official government publicity institution), Commerce and Industry, and Communications and Transport collaborated closely in controlling movement at the main land trade entry points that brought COVID-19 infections into Zambia - at Nakonde in the north, at Chirundu in the southeast and at Kasumbalesa, the main entrance from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) to the economic hub of Zambia, the mineralised Copperbelt Province. The DRC is a major market for Zambia. The DRC is also a major market for South Africa where the spreading of COVID-19. Zambia was the main transit state for trade but also for the spreading of COVID-19 between the two. That is despite South African and Zambia not sharing a border. Zambia was also a transit state for trade from South Africa to Malawi, Tanzania and other east African countries. Lusaka, Zambia's national and administrative capital was the main hotspot for COVID-19 from March 2020, partly because it is a key destination of trade from all Zambia's neighbours and an important refuelling station for transit traffic. Lusaka also had the biggest quarantine at the University of Zambia and the biggest COVID-19 treatment centre at Levy Mwanawasa University Teaching Hospital. The Kafue District, about 45 kilometres south of Lusaka, was another hotspot during this period. The map above also shows that hotspots are linked to active trade between Zambia and Tanzania. This led to the Nakonde border post and its environs becoming hotspots. Copperbelt Province, whose border with the DRC extends to the North-West Province (NWP), had more towns with infections than any other except for Lusaka Province. Zambian itinerant traders were active carriers of COVID-19 infections. Thus, it became recognised early enough that COVID-19 was both imported and locally generated in Zambia. This binary feature became a dominant idea that shaped national responses to the pandemic. The map also shows the infections spreading within the country. According to the country's oldest newspapers, the Sunday Times of Zambia and the Sunday Mail, of 19 April 2020, the Ministry of Health reported that positive COVID-19 infections had risen to 57 out of the 2 292 tests that had been done, mainly in Lusaka and Kafue, since 18 March 2020. A new and significant dimension was that there were now three COVID-19-related deaths. The Sunday Times of Zambia further reported that there were 8 534 high-risk cases under close observation in quarantine. There was some relief in that 2 435 people were released from a 14-day quarantine. Furthermore, three out of 25 COVID-19 patients in Lusaka were discharged. It was thus emerging that COVID-19 was a complex infectious pandemic. It was generally felt that the government had adopted a wise decision by managing foreign entry by air and by land.

The knowledge that many of the infections came from outside the country was no potential strength for evidence-based reactions and preventive interventions. As stated earlier, the first report was about a couple who holidayed for ten days in France before returning to Lusaka. Shortly afterwards, a group of 15 Zambians returned from Pakistan. Several individuals in that group who had symptoms of COVID-19 were quarantined in Lusaka Province and Copperbelt Province. Two of the infected were on the Copperbelt, Zambia's industrial hub. As the most economically developed province, there were more people there than in any other province involved in itinerant trading via Nakonde on the border with Tanzania, and Livingstone, and Chirundu in the south, which sources trade items in South Africa. Thus, the foreign and domestic origins of COVID-19 infections competed for government and public interventions. There was increased understanding of the linkages between foreign and local origins in tracing contacts of the group that may have imported COVID-19 from their visit to Pakistan. In Lusaka, two people and the residential areas where they lived were immediately put under COVID-19 surveillance. The driver who had transported the fifteen people who had visited Pakistan from the Kenneth Kaunda International Airport, and who was living in Jack Compound in the southern part of Lusaka, and a maid to one family in the group, who lived in Chaisa Compound, also in Lusaka, were monitored for coronavirus. The driver and maid both lived in Lusaka. The maid had the COVID-19 infection. The Zambia Daily Mail of 18 April 2020 reported her release from hospital where she had experienced rare pain and care she had neither seen nor heard of before.17 The movements of the group that had visited Pakistan led to the Government identifying six hotspots in Lusaka. These were in residential areas with high population densities and with relatively poor sanitation.18

Early COVID-19 social and economic impact

The Policy Monitoring and Research Centre (PMRC) produced one of the earliest social and economic reports on the impact of COVID-19 in Zambia.19The PMRC is a think-tank established in 2012 by the present governing party, the Patriotic Front, after winning the elections in August 2011. Thus, the PMRC has easy access to what we may consider authoritative data. Yet the PMRC has strengths and weaknesses of a typical research institution. In agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the PMRC noted a fall of 23 per cent in the price of copper, which was Zambia's leading export and earner of foreign exchange between March and August 2020. The PMRC reported that the price of copper fell from US$6 165 in January to US$4 754 in March. The PMRC also reported a worrying rate at which the national currency, the Kwacha, lost value in relation to Zambia's major trading currencies. The Kwacha depreciated by at least 20 per cent between March and August 2020. These findings led the PMRC to conclude that while national economic growth had been projected at 3,2 per cent of the gross domestic product in 2020, the economy would shrink by -4,2 per cent because of COVID-19. There were some hostile reactions to the early and anticipated deleterious impact of COVID-19.

Probably the most pointed negative response was Glencore's rejection of government guidelines on COVID-19. Glencore, a major shareholder in Mopani Copper Mines (MCM), invoked a force majeure on 8 April 2020. Glencore Plc had 73,1 per cent of shares in MCM. First Quantum Minerals Limited owned 16,9 per cent while the Zambia Consolidated Copper Mines-Investment Holdings (ZCCM-IH), representing the interests of the Zambian Government, had 10 per cent of the shares in MCM. The force majeure would take effect on 10 April. This timetable was a dramatic play which was difficult for many Zambians to comprehend. On 9 April 2020, The Times of Zambia called the Glencore move a "false'' majeure. This was a significant comment coming from a highly respected newspaper with strong ties to Zambia's nationalist history since the early 1960s. Yet, at a minimum, the action of Glencore should be analysed and understood in the context of certain laws on mining. In terms of The Mines and Mining Development Act, 2015, Glencore saw the early and anticipated effects of coronavirus as an act of nature which had reduced the price of copper to around US$4 80020 because of declining consumption of copper, especially in China, following the outbreak of COVID-19. In the short term, the future was bleak, and the Government was acutely aware of this.21 Therefore, Glencore, as the major shareholder in MCM, put their mines in Mufulira and Kitwe on "care and maintenance" for three months with effect from 10 April. A total of over 11 000 workers were put on leave for three months without any assurance of their jobs after that period. Glencore's response to COVID-19 had far-reaching ripple effects.

The Association of Supplies and Constructors, a grouping of small-scale Zambian entrepreneurs supplying a variety ofservices to the mining industry, were also adversely affected because MCM mining activities were expected to shrink in the context of Glencore's force majeure. The Association's services or supplies to MCM were bound to be reduced. In part, Glencore attacked sensitive elements in Zambian economic, nationalistic and patriotic traditions. In addition to uncertainty on the eventual effects of Glencore's action, the Government was surprised that another mining company, First Quantum Minerals Ltd (FQM), which dominated the "new" "Copperbelt" in North-Western Province of Zambia, had donated money to enhance capacity in dealing with COVID-19. According to Henry Lazenby,22 FQM donated US$530 000 to funds for managing COVID-19. This included US$100 000 to the North-Western Province's COVID-19 programme and US$90 000 to the Kalumbila District's COVID-19 programme. Kalumbila District is the home of FQM in Zambia. While charity begins at home, FQM donated US$340 000 to the national funds for COVID-19. This progressive position of FQM in Kalumbila was reported in one article in a local and radical newspaper, The Mast, on 17 April 2020. In another article, the popular tabloid showed that while FQM had limited influence at Kitwe and Mufulira mines because of its miniscule shares in MCM, it dominated mining investments in North-Western Province. There, FQM was forthright in standing shoulder to shoulder with Zambians and the Government in the fight against COVID-19. Thus, one of the immediate and major impacts of COVID-19 on the Zambian economy was about how to survive in trying times.

Glencore had not prescribed a remedy for survival. The mining giant provoked nationalistic and patriotic feelings among Zambians.23 The oldest mine workers' union, the Mineworkers Union of Zambia (MUZ), and the union of most experienced and skilled workers, the National Union of Miners and Allied Workers (NUMAW), called on the Government to nationalise the MCM. The Government initiated nationalisation but was stalled by the Glencore court action in a South African court. Several civil society groups protested the decisions of Glencore. Members of Parliament from Copperbelt Province constituencies grouped and collaborated in expressing solidarity with the miners and the government. Populist print media such as News Diggers and The Mast and traditional print media, Times of Zambia and Zambia Daily Mail, reported protests in ways that strengthened the hand of Government for nationalising MCM. In part, this would mean buying Glencore's 73,9 per cent shares in MCM. Thus, the mood in the media and civil society organisations was one of condemning Glencore. This encouraged the Government. Strangers had become bedfellows against mining capital while the Government sought a bumper political harvest. Dichotomy and alliances have been highly visible features of social change in Zambia's political history since the late 1940s.

These responses reflected complex and compounded developments in the spreading from within the country and management of COVID-19. A chain of high profile COVID-19 infections precipitated major changes in many institutions. The Minister of Information, who is also a government spokesperson, was reported infected on 21 May. The pandemic infections moved high up when the republican vice-president was reported infected on 17 July. Two members of parliament were infected and died from COVID-19 in July. One reaction was that Parliament suspended its sitting. On 10 August, some United Nations staff were reported infected. Consequently, the United Nations offices were closed. Many institutions and working styles changed. In promoting effective social distancing in the workplace, workers were grouped and allocated some days when they would work in their offices, instead of all workers reporting for office duties daily between Monday and Friday. Meetings were reduced to those considered absolutely essential and were done through Zoom. This led to radical thinking among some employers about the size and salary structures of their employees. Equally radical was a requirement of many institutions that people seeking services should wear masks. Facilities were provided for the washing of hands before entry into any office. The body temperature of all visitors was taken and recorded as a preparation for tracing contacts where that became necessary. This apparent orderliness may have protected some salariats in formal employment.

Joint research involving the United Nations institutions, the Government of Zambia, development partners and civil society organisations between June and August revealed disturbing social practices and occurrences related to COVID-19 in urban residential areas and the education sector, starting with preliminary reflections on impact of COVID-19 in urban, high-density residential areas. These official and written reports should have corroborated oral evidence that brought out real lived experiences in high-density, urban residential areas. These were testimonies from residents in these compounds. Jane Mwansa from Mutendere Compound who was working as a maid said:24

COVID has stopped many people going to hospitals. They particularly avoid government hospitals because insistence on wearing masks and social distancing are enforced where there is COVID-19. Private hospitals and clinics attend to patients without masks.

In Bauleni Compound, Bertha Tembo stated:25

...people fear to be infected at hospitals. A few people who have to go to hospital are happy that these days they do not wait for a long time before they receive treatment. Some of these [people] wear masks. That is why they are quickly attended to. My friend had no mask but was very sick. The doctors avoided her and advised her to buy a mask. When other patients told the doctors that she was going to die because of masks. After that she was given medicine.

United Nations-led research reported that on 17 July that there were 42 deaths out of 1 895 infections. There were 24 people who were brought in dead (BID), "highlighting the likelihood of wider prevalence in the community" with a "higher community transmission and severe cases not seeking treatment from health facilities".26 Further, "the majority of the new cases [were] locally transmitted"27 with over 80 per cent of deaths occurring outside health facilities. These occurrences were both the cause and result of low, inadequate and inconsistent national laboratory testing. The high death rate in certain urban locales was due to poor compliance with prevention measures such as the use of masks, hand-washing hygiene and physical distancing. I attest to these based on my attendance at church services, weddings and family contacts. Because of COVID-19, over 75 per cent of deaths in Lusaka occurred in high-density population areas. There was an increase of 16,9 per cent on BIDs at the University Teaching Hospital in Lusaka between January and July 2020 compared to the same period in 2019.28 These experiences and the COVID-19 prevalence survey done between 2 and 30 July 2020 in Lusaka, Livingstone, Kitwe, Ndola, Nakonde and Solwezi led the Ministry of Health to launch a national strategy for reducing new infections.

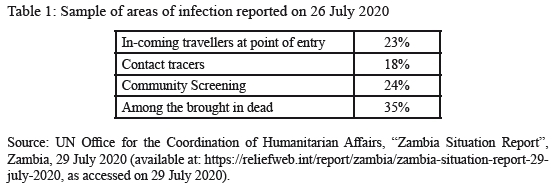

The cornerstone of the strategy was "to encourage public compliance to public health measures". The United Nations agents had earlier established that "poor compliance by the public to recommended prevention measures such as use of masks, hand hygiene and limited laboratory testing remain key challenges to the COVID-19 response".29 Despite the spread of infections being known, especially in July and August, as demonstrated in the map above, the new strategy focused on residential areas where non-compliance and the death rate were higher than other geographical areas and social groups. From late July and early August, the Ministry of Home Affairs deployed the police in generally low social class residential areas to enforce COVID-19 public health measures. Individuals without masks were to be arrested and fined K750.30 Restrictions imposed in early March began to be relaxed on 10 April 2020 because of loss of income by street venders, bars, casinos and restaurants. The COVID-19 reduction strategy also targeted people who entered Zambia. Certificates showing negative COVID-19 infection within the previous 14 days were required for travellers entering the country. Exit for Zambians, especially itinerant traders, was severely restricted. One sample of infections reported on 26 July reflects the sensitivity and evidence base of new restrictions from end of July as shown in the table below:

Managing COVID-19 in the education sector reveals the incapacity of the Zambian Government to manage the pandemic effectively and deal with social justice. Early in March, primary schools, secondary schools and all institutions of higher learning were closed in order to prevent the spreading of COVID-19 infections and facilitate effective management of the pandemic. According to one civil society organisation, Innovation for Poverty Action (IPA), 4,4 million schoolchildren were affected. Even worse, "feeding programs for disadvantaged children were suspended".31There were 97 000 learners on the school feeding programmes. The IPA further reported that between March, when education institutions were closed, and 1 June when learning resumed, 50 per cent of primary school children spent time without learning at home. In respect of secondary school pupils, 35 per cent were not learning, 20 per cent learned through education broadcasts from the Zambia National Broadcasting Services, and less than 2 per cent used radio broadcasting. The greatest incapacity was that most teachers lacked skills for distance teaching and assessment of learners' activities. This was not unusual because in 2015, Grade 9 examinations were sat in schools including those that had no computers.32

Thus, in the education sector, the impact of COVID-19 was diverse, and a better understanding awaits further research.

The past in dealing with COVID-19

The past is usable in many contemporary challenges. This study is, in part, a link between past and future policies and studies on how Zambia responded to emergencies. The United Nations agencies in Zambia supported a survey in July which acknowledged that the country faced COVID-19 at a particularly critical time after recent outbreaks of cholera and food insecurity from consecutive droughts from 2018.33 From June 2019 to about the time of the unfolding of COVID-19 in early 2020, there was a countrywide gassing of innocent people with the intent of drawing blood from victims.34 The gassing paralysed victims who became helpless and failed to protect themselves. Targets were gassed in their houses at night. Other victims were attacked by gangs in isolated sites. There was an organised mass response in which many suspects were killed. In one unfortunate incident, a young man in Kaoma District did not know that he had participated in killing his innocent uncle.35 The Ministry of Home affairs coordinated security wings in collaboration with the Ministry of Health. The Disaster Management and Mitigation Unit (DMMU) in the Office of the Vice-President offered expertise in managing COVID-19 as another disaster or emergency. It is thus worth noting that various role players sought to draw on how the government, various institutions or the population handled earlier emergency experiences. The multi-sector approach established at Cabinet level was deployed as the UN agencies, diplomatic offices and their development agencies, and civil society organisations collaborated in their responses to COVID-19.

The central strategy of these multi-sector approaches was drawn from the fact that "poor compliance by the public to recommended prevention measures such as use of masks, hand hygiene and limited laboratory testing, remain key challenges to the COVID-19 response".36 Drawing from accumulated experiences on handling emergencies and with growing evidence on possible best practices for managing COVID-19, the Ministry of Health launched a National Strategy for Reducing New Infections of COVID-19. The framework of this strategy was "to encourage public compliance to public health measures".37

On 17 July 2020, the National Epidemic Preparedness Committee was emphatic that a progressive way forward was for "greater emphasis of public compliance to public health measures".38 This contrasts with a false assertion that COVID-19 in "Zambia had claimed democracy, not human".39 Because compliance was weak, early in August, the Government deployed the police to close service businesses such as bars, casinos and restaurants. A fine of K750 was to be imposed on those who did not comply with COVID-19 public health measures. Local authorities threated to cancel business licences for non-compliance. It is clear that COVID-19 nurtured institutional evolution and increased state intervention based on past experiences. Thus COVID-19 demonstrated intersections of social, political and economic histories.

It is evident that scholarly studies of COVID-19 will be a significant addition to social, economic and political historiography of Zambia. That endeavour will be grounded, at least, in a series of studies on the Spanish Influenza of 1918-1919. These studies deal with rumours on what the influenza was as one form of response among Africans in a colonial situation. They also deal with aspects of negligence of African populations in implementing remedies to contain the pandemic. Social and economic studies will call further attention because of the large number of deaths, including increased death rates when compared to previous pandemics or outbreaks of diseases. On this, there is a rich starting point in Zambian social history. Walima Kalusa, at times in collaboration with Megan Vaughan,40 wrote on complex relationships between death and politics in central Africa. It is instructive that such studies emerged during the era of high death rates due to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). It is further instructive because of multiple and mixed use of sources and research methods involved. Triangulation requires long-term study perspectives because of changing analyses of diverse content in sources and methodology. Such future research may find a valuable beginning in the present discussion.

Conclusion

Teaching or learning and research in history on COVID-19 in Zambia calls for a multidisciplinary approach. This discussion shows at least four issues in shaping scholarship and state policies. First, COVID-19 brings out new insights in the history of globalisation with diverse voices and connections. Second, local dynamics in Zambia are as diverse as agents of change at a global level. Different social classes and sectors of the Zambian population were affected differently and responded in ways that reflected their social positions and political orientations. The dynamics were persistent in the hope of containing the pandemic rather than seeming helpless and hopeless. Future studies will analyse these enduring transitions better than a contemporary investigation could. The majority of written sources are official frontline reports. Detailed oral data from frontline workers will be useful. Third, sources of data are diverse in terms of written and oral categories. Coordinating voices from these sources will be challenging yet inspiring tasks. Fourth, and finally, skills in multidisciplinary research and use of diverse sources will be essential in understanding COVID-19 as medical, social and political histories. The diversity of sources implies, in part, that learner engagement in learning and research could advance schooling.

1 Despite a lack of consistently high academic ratings, the informative and inspiring starting point on the history of Current History is Wikipedia.

2 M Macmillan, "The Archduke's assassination came close to being just another killing", The Globe and Mail, 27 June 2014. These are among the leading newspapers in forming opinions and public history in Canada.

3 ME Ochonu, "Elusive history: Fractured archives, politicized orality and sensing the postcolonial past", History in Africa, 42, 2015, pp. 287-298.

4 Zambia Daily Mail, 19 March 2020.

5 UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, "Zambia Situation Report", Zambia, 29 July 2020 (available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/zambia/zambia-situation-report-29-july-2020, as accessed on 10 September 2020).

6 Zambia Daily Mail, 6 March 2020; News Diggers, 6 March 2020.

7 Africa Confidential, 4 September 2018. On 30 January 2020, the publication reported that a Chinese company would take over Zambia Electricity Supply Company Ltd if the debt was not paid.

8 Email: MM Kaunda (History teacher)/AM Kanduza (Professor), 21 September 2020.

9 Discussion with AM Kanduza, 21 August 2020.

10 UN Country Team in Zambia and UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, "UN COVID-19 Emergency Appeal: Zambia, May-October 2020" (available at Desktop/COVID-19%pandemic%20in%Zambia; UN COVID-19, as accessed on 25 August 2020).

11 UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, "Zambia Situation Report", Zambia, 14 September 2020 (available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/zambia/zambia-situation-report-14-september-2020, as accessed on 20 September 2020).

12 Republic of Zambia, Statement by His Excellency, Dr Edgar Chagwa Lungu, President of the Republic of Zambia on COVID-19 Pandemic, Wednesday, 25 March 2020.

13 Republic of Zambia (ZM), Statement by His Excellency, Dr Edgar Chagwa Lungu, President of the Republic of Zambia on COVID-19 Pandemic, Wednesday, 25 March 2020.

14 UN Country Team in Zambia and UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, "UN COVID-19 Emergency Appeal: Zambia, May-October 2020" (available at Desktop/COVID-19%pandemic%20in%Zambia; UN COVID-19, as accessed on 25 August 2020).

15 Often, Zambia is known to have eight neighbours, namely, Angola, Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Malawi, Tanzania and Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

16 UN Country Team in Zambia and UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, "UN COVID-19 Emergency Appeal: Zambia, 17 July 2020" (available at Desktop/COVID-19%pandemic%20in%Zambia; UN COVID-19, as accessed on 25 August 2020).

17 Times of Zambia, 20 April 2020.

18 The World Bank, Zambia in the 1980s: A historical Review of Social Policy and Urban level Interventions (Washington, The World Bank, July 1883), p. 4; UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, "Zambia Situation Report", Zambia, 29 July 2020 (available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/zambia/zambia-situation-report-14-september-2020, as accessed on 19 September 2020).

19 Policy Monitoring and Research Centre, Zambia Reports, 19 September 2020.

20 Forecasts show the copper price in 2021 ranging between US$7 000 and US$12 000.

21 ZM, Statement by His Excellency, Dr. Edgar Chagwa Lungu, President of the Republic of Zambia on the COVID-19 Pandemic, State House, Lusaka, 25 June 2020, pp. 8-9.

22 H Lazenby, "Zambia: Mining company joins fight against COVID-19", Mining Journal, 8 April 2020.

23 Zambia Daily Mail, 10 April 2020.

24 J Mwansa (Domestic worker - 33 years, Grade 12, House 76), oral interview, Mutendere compound, 22 July 2020.

25 B Tembo (Mother of four, 37 years, Grade 9), oral interview, (AM Kanduza), 25 July 2020.

26 UN Country Team in Zambia and UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, "UN COVID-19 Emergency Appeal: Zambia, May-October 2020". Developed in May and revised at end of July 2020 (available at https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/zambia, as accessed on 8 September 2020).

27 UN Office for the coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, 20 August 2020 (available at https://reports.unocha.org/en/country/Zambia, as accessed on 7 September 2020).

28 UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, "Zambia Situation Report", Zambia, 14 September 2020 (available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/zambia/zambia-situation-report-14-september-2020, as accessed on 20 September 2020).

29 UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, "Zambia Situation Report", Zambia, 29 July 2020 (available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/zambia/zambia-situation-report-29-july-2020, as accessed on 10 September 2020).

30 Times of Zambia, 11 August 2021; Zambia Daily Mail, 12 August 2020.

31 Innovations for Poverty Action, COVID-19 Response Survey, Lusaka, 2020.

32 Personal recollection.

33 UN Country Team in Zambia and UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, "UN COVID-19 Emergency Appeal: Zambia, 17 July, 2020" (available at https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/zambia, as accessed on 8 September 2020).

34 ZM, Press Statement by Mr Kakoma Kanganja, The Inspector General of Police on the Security Situation in the Country, 22 February 2020.

35 Zambia Daily Mail, 23 January 2020 (available at https://reliefwebrint/report/zambia, 29 July 2020, as accessed 31 August 2020). Colleagues and I suspended early morning health walks because of fearing gassing.

36 UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, "Zambia Situation Report", Zambia, 29 July 2020 (available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/zambia/zambia-situation-report-29-july-2020, as accessed on 31 August 2020).

37 UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, "Zambia Situation Report", Zambia, 14 September 2020 (available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/zambia/zambia-situation-report-14-september-2020, as accessed on 20 September 2020).

38 UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, "Zambia Situation Report", Zambia, 29 July 2020 (available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/zambia/zambia-situation-report-29-july-2020, as accessed on 31 August 2020).

39 News Diggers, 15 June 2020.

40 WT Kalusa and M Vaughan, Death, belief, and politics in central African history (Lusaka, Lembani Trust, 2013).