Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Yesterday and Today

On-line version ISSN 2309-9003

Print version ISSN 2223-0386

Y&T n.24 Vanderbijlpark Dec. 2020

HANDS-ON ARTICLES

Creating a collaborative learning environment online and in a blended history environment during Covid-19

Kirstin Kukard

Herzlia High School, Cape Town, South Africa. kirstinkukard@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Collaboration is key to an effective history classroom. Discussion, peer work and learner engagement facilitate the development of historical thinking skills, understanding ofhistorical content and a careful engagement with the ethical issues posed in studying history. The realities of teaching online and then in a blended learning environment during COVID-19 have created challenges for maintaining this collaborative environment. The article discusses a number of techniques that have been employed to foster general engagement and also to scaffold assessment.

Keywords: Collaboration; COVID-19; Group work; Peer learning; Constructivist learning.

Introduction

In the context of teaching in a global pandemic, one of the greatest challenges has been maintaining a sense of collaboration and connection. In a classroom environment, there are a number of strategies that I regularly make use of, such as frequent trio work, regular informal peer assessment and physically interactive tasks, such as card sorts. In an online or blended environment, the strategies I took for granted became more of a challenge. The following article is a discussion of the methods I have used to try and keep the culture of collaborative learning alive in my history classroom during the Covid19 pandemic.

The school in which I teach is one of the privileged few in our South African context who were ready to shift into online learning fairly seamlessly. We are a Google school and had made extensive use of Google classroom prior to the pandemic. Our school also encourages innovative, technology-based teaching and I have used online quizzes and other tools in the past. All of our classrooms have computers and projectors and I make use of Google slides in all of my teaching. I am very conscious that our privileged environment is the exception not the norm in our South African context. I know that the resources of both our school and our learners are not available to the vast majority in our country. I hope that despite this, that some of these techniques could perhaps be adapted to less data intensive media, such as WhatsApp.

Our school was the first to close in South Africa due to a parent testing positive for COVID-19. This was before wider lockdown measures were introduced. We were teaching online within a day (Presence, 2020: online). Fairly early on, our principal made the decision that we would remain online for the duration of Term 2, even for the Matrics. Our grade 10 to 12 learners had elective subjects like history every second day. We engaged for forty-five minutes on a live video conferencing session and they were expected to work asynchronously on the alternate day. Since the beginning of our Term 3 (4 July 2020), we have been using a blended approach and continue to do so at the time of writing (September 2020). We have half of our learners at school on one day, and the alternate group the next day. Our Matrics have been coming in every day. As a private school, we have also had permission for our other grades to be at school. While I have thoroughly enjoyed face-to-face teaching again, the blended approach presents its own challenges.

The discussion which follows is by no means intended to be presented as the best possible practice. Instead, I wanted to take the opportunity provided by this special issue of Yesterday & Today to reflect a bit on my own teaching experience and consider what has worked and what has not. In the process, I also wanted to reflect on how teaching during this time has made me think through aspects of best practice in history teaching more generally; this has personally challenged me to think about how these techniques can be introduced more consistently even in post-pandemic classrooms.

The importance of collaboration in learning history

The major challenge I found with online teaching was the issue of collaboration. It is well beyond the scope of this article to engage in a full discussion of the merits of an active learning, constructivist approach to education, but these ideas have been very influential in my own teaching practice. It is the process of "social interaction with a more competent person that drives cognitive growth" (Bergin & Bergin, 2014:123). The process through which this interaction takes place requires opportunities for discussion with peers and the teacher; it also requires a scaffolded process of modelling skills, which provides opportunities for learners to work at these skills incrementally and then to move towards using the skills independently (Bergin & Bergin, 2014:123). Both teacher and peer collaboration allow for learners to co-construct the skills needed to be successful in a subject. In an online space, a lack of "social presence" can negatively impact both the learners" perceived and actual understanding of the work and the development of these skills (Wei, Chen & Kinshuk, 2012:503).

"Human interaction lies at the heart of the disciplines" in the social sciences (McCarthy & Anderson, 2000:280). As such, the collaboration and social interaction discussed above becomes even more significant in a subject like history. The particular kinds of cognition which need to be developed through history education involve the ability to engage with historical concepts such as change and continuity, significance, cause and consequence, working with evidence, and historical perspectives (Seixas & Morton, 2013). The process of acquiring these ways of thinking may be through teacher focused activities (Bergin & Bergin, 2014:131). However, "children learn by thinking" and learners need to be actively engaged in order to facilitate this process of thinking (Bergin & Bergin, 2014:131). The more traditional history models which focus on transmission and recall do not sufficiently foster this (Seixas & Morton, 2013:3). The process of collaboration not only supports this cognitive process, but also facilitates navigating the ethical dimension of history teaching (Seixas & Morton, 2013:6). As such, collaboration and discussion are central to an effective history classroom.

I must be quick to say that this is the kind of history teaching I aspire to. I still frequently find myself packaging essay outlines in easily digestible formats which will produce good outcomes in a Matric examination but have little educational value in teaching learners to think for themselves. Despite the immense privileges I have, I often find myself overwhelmed and too busy, and happy just to use the textbook to explain an idea, or rushing through a section "delivering the curriculum" as if it were a neat package. I and my history teaching are very much a work in progress. Be that as it may, the examples explored below are part of how I navigated my journey towards creating a classroom which fosters historically rigorous and humane thinking, even during COVID-19.

Trying to foster collaboration online

My classroom is generally set up in rows with groups of three desks. Throughout the course of a normal lesson, there would be multiple opportunities for learners to shift into their trios, either to discuss a historical source, develop an opinion on an historical issue or complete other activities. I find that this setup allows for frequent collaboration. I set my classroom up so that there is a mix of abilities within each trio. In an online learning space, this is clearly not feasible. Although my lesson plans still included the discussion points or activities, initially it seemed that there were no easy ways to ensure that all learners were engaging with these.

In a purely online space, I found that learners are far less likely to discuss and engage. I did still make use of open discussion questions but found that these worked best when analysing an historical source, such as that shown in Image 1. This kind of open question worked reasonably well in that a number of learners were able to engage with aspects of the painting's message.

Once some learners had mentioned what they could see in the painting and how this tied in to its message, I was able to follow up with further questions to encourage a deeper interpretation. This cycle of questioning encouraged other learners to contribute. Although this worked reasonably well, it was still the case that only a limited number of learners gave their perspectives.

If I put a general question to the class, especially if it was only verbal, I generally had one or two learners who spoke the most. This was compounded by the fact that for the sake of managing data usage, most learners kept their cameras off for the entire lesson. It therefore became difficult to know whether they were engaging at all, let alone forming ideas which they were prepared to share. I found that this was particularly challenging with my grade 10s, as I had only taught them for a term and did not feel that I had a firm relationship with them yet. Although quick trio discussion and sharing was not a feasible option, I found a number of techniques which helped to get feedback from the whole class and ensure that they were all engaging.

The first technique was to use a variety of historical resources which gave each learner the opportunity to formulate a response in writing rather than needing to speak out loud over the video chat. The simplest format of this was to make use of the chat feature on the video conferencing application (in our case, Google Meet). I would pose the question to the learners both verbally and through a shared slide view. I would then ask each of them to write a response in the chat bar. Sometimes this answer would be a very simple one and at other times it would involve a more detailed response. If I thought of a question that I wanted answered, which was not on the slideshow as part of my lesson plan, I would generally type the question into the chat box rather than just speaking it so that learners were able to engage with it in both written and verbal form. This generally worked fairly well and was definitely the quickest way to get a response. However, I found that in some cases, there were still learners who did not type in an answer, or who would wait for a number of other learners to answer first and look at their response before venturing their answers. In some cases, this was a good thing - the equivalent of being able to discuss with a peer before needing to share an idea with the class as a whole. However, in some cases, I could tell that learners were mimicking their peers' answers without real understanding. The best solution to this was to make use of historical resources which required learners to respond before they could see anyone else's feedback.

The first example of this was a resource called AnswerGarden.

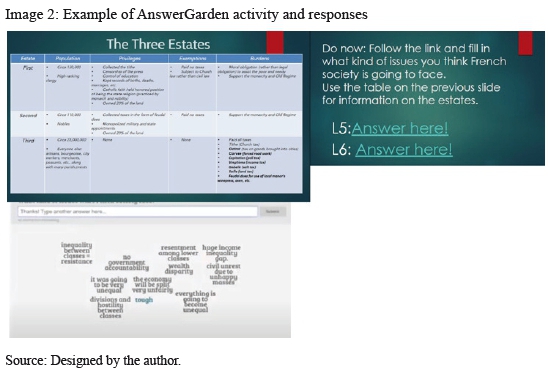

As shown in Image 2, the task required learners to engage with some statistics on the three Estates in pre-revolutionary France. Learners needed to predict what problems French society was going to face based on this information. Their responses were recorded through an AnswerGarden question link. They were each required to write a short response and then would see a word cloud of others' responses. Once most learners had answered, I could discuss various points which were raised in the word cloud. This worked fairly effectively because it allowed learners to think of their own response and share it. It did not completely solve the issue of some learners not responding, but the curiosity of wanting to see the word cloud emerge did entice more of them to respond.

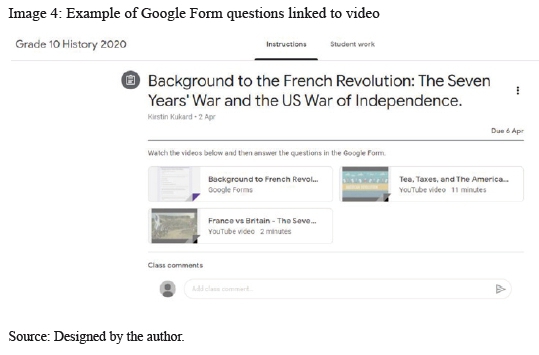

Another technique which I found worked well was to pose a question in Google classroom. I could ask learners to respond to this before the lesson and begin the lesson with a discussion of the ideas which emerged. In some cases, this question was based on a video to be watched before the lesson, as seen in Image 3. This flipped classroom method also allowed for learners to engage with ideas in their own time rather than under pressure in a live lesson.

In some instances, rather than using the "Question" feature on Google Classroom, I made use of an "Assignment" feature with a Google Form based on the video such as shown in Image 4. This allowed me to engage more carefully with the learners' responses. Google Forms allows for the form creator to see an aggregate of all learners. This provides an opportunity to clarify any concepts which may have been misunderstood. One is also able to see individual responses in order to check on how particular learners have understood the work.

Although these flipped classroom models work well as part of a "normal" teaching experience, I found them particularly useful during this time.

When we moved to a blended learning approach, new opportunities and challenges presented themselves. It is much easier to ensure that those learners who are physically present are engaged. It is much harder to ensure that the other half of the class who are at home are feeling as much a part of the lesson. Although some of the above-mentioned techniques have remained useful (particularly using the quick response of the chat feature), I have adopted some additional strategies.

We have begun the section of work on "Topic 4: Transformations in Southern Africa" with our grade 10 classes. Last year, we made use of a series of lessons first developed by Kate Angier and Gill Sutton.

These lessons make use of a variety of active learning techniques and, when done in person, help learners to develop historical thinking skills and remain engaged in what can sometimes be a slightly dry section of work. However, we were faced with the challenge of engaging with this material in a blended learning environment where half the class was physically present and half was online. Our solution was to group learners in trios across the two groups so at least one learner would be in class at all times. They communicated over WhatsApp or in the chat feature on shared Google documents. This has proved to be an effective technique as it allows me to set longer form activities and to be sure that those online remain engaged. For example, one such activity was sorting sources on life in Southern Africa by 1750, first into categories that made sense to the learners and then into economic, social, trade and political. Learners had access to the sources through a resource on the Google classroom. They were then able to work in a shared Google document to copy sections of the sources into the various categories such as shown in Image 5.

Under usual circumstances this would all have been done hard copy and involved making large posters. I feel that the tactile element of the sorting is still more effective, but the online version was a good workaround under the circumstances. I was able to move around the class (with suitable social distancing) and engage with the learner who was in class and see what the others were contributing to the document. All learners then shared their documents with me, so that we could do a virtual "gallery walk" (Facing History and Ourselves) of the documents and see how different groups had worked with the sources.

Another example of working between online and in class was with my two grade 11 classes. We were beginning the section on competing nationalisms in the Middle East. As I teach at a Jewish school, this topic needs to be taught in a sensitive, whilst historically rigorous way. My lessons are partly drawn from a series of lessons developed by Facing History and Ourselves (Darsa, 2018:1617). The focus is on understanding the competing narratives around the history of the region. One of the introductory activities I usually do in person is to have learners read various viewpoints on the conflict and to engage with these in the form of a "silent conversation" (Facing History and Ourselves, 2020). Under normal circumstances, the learners would move around the room silently to look at various large posters and write their responses either to the quotation, or to other learners' comments. We would then look at a few examples of these interactions together and allow this process of listening to frame the rest of the section. Given the constraints of blended learning, I needed an alternative. Instead of physical posters, I had the quotations on a Google document which was shared with the learners. I gave them all editing access. They were each asked to go onto the document and to add comments to the quotation. As you can reply to a comment, this also allowed learners to engage with others' comments much as they would have done in the physical classroom. We kept the same documents across both classes, so that the second class was able to see the first class's interactions. This activity spanned two lessons, so we could reflect back on the overall discussions. Again, I do feel that the physical process would probably have been more effective but this version did at least allow us to have some of the relevant conversations at the beginning of the section of work.

Through these various technologies and techniques, I was therefore able to try and keep learners engaged in a collaborative, active learning process both online and in a blended model. I certainly still found myself slipping too much into a "teacher-talk" mode, particularly when learners seemed a bit disconnected but these techniques helped to offset that somewhat.

Collaboration in assessment

One of the areas in which I feel I have the most potential room for growth is in allowing time for regular collaborative assessment. Instead ofjumping straight to a test, I hope increasingly to allow time for developing the skills of historical thinking in a collaborative format. By the time a summative assessment comes along, the goal is for learners to have mastered the various elements required so that they are able to demonstrate their ability with confidence.

The process of teaching at this time has made me even more aware of how important this is. In a pre-Covid classroom environment, we had more opportunities for frequent timed assessments. In a purely online environment, this became less of an option and I needed to find alternatives which would develop the necessary skills.

For both my grade 10s and 11s, we focused on essay writing during the period when we were teaching purely online. For the grade 10s, this was the first time that they were being taken through the process of writing an essay. In order to facilitate this process, I created a series of short videos using the free version of Screencastify.

These videos were all less than five minutes long and went through all of the aspects of essay writing: how to write an introduction, using the PEEL method for developing the line of argument in the body of the essay, and how to create an effective conclusion. The PEEL structure helps learners to build their paragraphs through using an opening topic sentence (Point), elaboration (E) and evidence (E) to build the argument and then a link (L) back to the question. Learners were expected to watch these videos asynchronously so that they had time to watch at their own pace. The answers modelled in the videos were also available to the learners to refer to.

During lesson time, we made use of the video conferencing platform Zoom. I spent the first few minutes of the lesson reinforcing the key concepts of the relevant aspect of the essay and allowing for questions. I had pre-created breakout rooms and assigned learners into groups of four. In the first lesson, learners moved into their breakout rooms and discussed their position on the stance of the essay question: "'The political situation in France was the most significant cause of the French Revolution'. To what extent do you agree with this statement". They had to agree on their stance as a group and work on writing their introduction. As we were writing the classic "causes of the French Revolution" essay, learners were each responsible for writing a paragraph about one cause. By the end of the first lesson, each learner knew which paragraph they would be writing and could ensure that they were prepared for the next lesson. They were also asked to share their document with me. The breakout room feature allows the host to move between rooms. I was therefore able to join each group in turn and ensure that they were on track. The chat feature also allowed learners to directly message me and ask me to join their group if they were struggling. In the following lesson, we reinforced the process of writing the PEEL paragraphs. Learners then moved into their groups again and began working simultaneously on their various paragraphs. I joined rooms that needed me, but mostly spent time on the various groups' documents giving feedback to learners. They had a follow-up lesson, where they were asked to give feedback to their group members on their paragraphs using the quick peer feedback structure of "What went well" and "Even better if". They then made any necessary changes and then finalised their conclusions. These group essays were submitted for assessment through the Google classroom.

Once I had marked and given feedback on the group essays, learners were then expected to write an individual essay on the new topic: "'Louis XVI's reckless spending and failure to reform the taxation system launched the French Revolution'. To what extent do you agree with this statement?" They were able to draw on the group essays in formulating this essay, but needed to adapt their line of argument to engage with the relevant question. This collaboration therefore allowed for a scaffolded version of the essay writing process with both peer and teacher feedback.

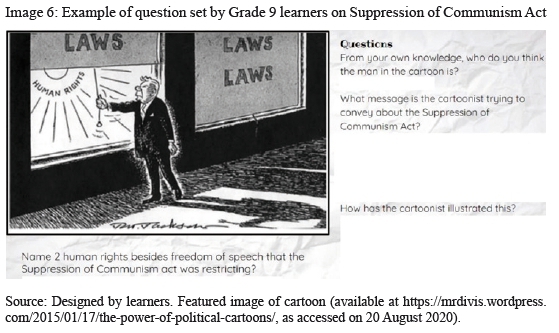

Although the next example is by no means a novel one, it has shown me the importance of allowing learners to explore ideas for themselves. Our Grade 9s have been learning about the history of apartheid. Rather than teaching the apartheid laws, we asked the learners to work either in pairs or in groups of three. They produced a slideshow on Google slides, explaining what their law was about and giving some examples of how it affected people's lives. They were then asked to find one written and one visual source and to set historical questions on each of these, such as shown in the example in Image 6.

The learners were given a few lessons in class to work on this. In most cases, one of them was in the classroom while the other was online. The learners mostly chatted on WhatsApp, sometimes over calls, to work on the various aspects of their slides. I was able to answer questions and look at examples of their work by engaging with those who were in class, or giving feedback to those who shared their work with me. At the end of the cycle of lessons, each group presented on their law. I selected the most interesting question from their list and asked the rest of the class to answer it. The group then gave their feedback on the answer. The presentations were therefore less like a formal oral and more of a springboard for discussion. I asked frequent questions and clarified points throughout. We created a shared Google document highlighting the key features of each law as we went along as these lessons provided the teaching aspect of these laws. While some learners certainly produced better results than others, overall, they were far more engaged with the process than if I had simply taught through the laws myself. This process also ensured that every learner had a chance to speak, even if (as is the case with some of the learners) they are only attending school online.

Conclusion

The process of teaching history online and in a blended approach has highlighted once again for me how important it is to try and keep learners engaged and collaborating in the process of their own learning. The strategies mentioned above are certainly not completely new nor fool proof. I still found that my weakest learners struggled disproportionately. There were a number of learners who battled with motivation and mental health issues such as depression and anxiety during this time. Those learners who usually struggle with executive function struggled more so without the physical presence of a teacher to nudge them along. There were some learners who barely submitted any work and would avoid engaging in discussion or feedback in whatever form it took. The above strategies also favour those who have reliable internet and easy access to devices. While this is the majority of our learners, I needed to find workarounds for those for whom these were more of a struggle. I am certainly of the opinion that being in the same physical space is the best way to foster the relationships and intellectual space to learn. However, given the constraints placed upon us at this time, these strategies helped to maintain this atmosphere to some extent.

Overall, this time of isolation and forced separation from my learners has led me to be more committed to working at continuing to build collaborative learning into my regular teaching practice. While some of these techniques may still work best (and require less effort) in a physical classroom space, the constraints of teaching history online or in a blended environment have also pushed me to think creatively.

References

Bergin, CC & Bergin, DA 2014. Child and adolescent development, 2. Cengage, Stamford: USA. [ Links ]

Darsa, J 2018. Colliding dreams: Study guide draft, Study Guide ed., Facing History and ourselves. [ Links ]

Facing History and ourselves 2020. Big paper: Building a silent conversation, Homepage. Available: https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/teaching-strategies/big-paper-silent-conversation. Accessed on 29 August 2020. [ Links ]

Facing History and ourselves, Gallery walk, Homepage. Available: https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/teaching-strategies/gallery-walk. As accessed on 29 August 2020. [ Links ]

McCarthy, JP & Anderson, L 2000. Active learning techniques versus traditional teaching styles: Two experiments from History and Political Science, Innovative Higher Education, 24(4):279-294. [ Links ]

Presence, C 2020. 12 March 2020-last update, Coronavirus: Herzlia closes its schools, awaits outcome of parent's COVID-19 test, Homepage of News24. Available: https://www.news24.com/news24/southafrica/news/coronavirus-herzlia-closes-its-schools-awaits-outcome-of-parents-covid-19-test-20200312. Accessed on 25 August 2020. [ Links ]

Seixas, P & Morton, T 2013. The big six historical thinking concepts. Toronto: Nelson Education. [ Links ]

Wei, C, Chen, N & Kinshuk 2012. A model for social presence in online classrooms. Educational Technology Research and Development, 60(3):529-545. [ Links ]