Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Yesterday and Today

On-line version ISSN 2309-9003

Print version ISSN 2223-0386

Y&T n.24 Vanderbijlpark Dec. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2223-0386/2020/n24a8

ARTICLES

Teaching historical pandemics, using Bernstein's pedagogical device as framework

M Noor Davids

University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa. davidmn@unisa.ac.za; ORCID No.: 0000000328943951

ABSTRACT

On 11 March 2020, the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared COVID-19 a global pandemic. This announcement came as a shock to countries around the world. Diverse responses across the globe exposed an ill-prepared world that lacks the historical consciousness and capacity to manage and fight off a global pandemic. Mitigation of COVID-19 requires, inter alia, knowledge of best practices, in which case memory of the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic comes to mind. This event claimed the lives of 50 million people,1 which is more than the number of people who died during the two 20th century world wars. Responding to the arguably poor historical knowledge of pandemics, this article presents an exploratory proposal to integrate historical knowledge of pandemics with History teaching at school. Considering Bernstein's pedagogical device as a conceptual framework, the article responds to the question: how can historical knowledge of pandemics be integrated with History teaching? A small qualitative sample of online responses from History teachers (N=15) was used to gather a sense of how practicing History teachers relate to historical pandemics in the context of COVID-19. Their responses assisted in opening a discussion around knowledge production, recontexualisation and reproduction during the design process. Based on the expectation that knowledge of pandemics will be taught in the history classroom, recommendations for teacher education are suggested.

Keywords: COVID-19; History teaching; Knowledge production; Pandemic; Pedagogical device; Recontextualisation; Reproduction.

Introduction

As the world struggles to come to grips with the devastation and uncertainty of the COVID-19 pandemic,2 teachers are anticipating curriculum proposals that will integrate historical knowledge of pandemics with their classroom teaching. Teachers at primary, secondary and higher education intuitions, across all disciplines, will be expected to create curriculum space to teach pandemics as a phenomenon. History teachers are confronted with the need to teach historical knowledge of pandemics. In the early stages of COVID-19, a group of scholars have been proactive in sharing their ideas and imaginations of a post-COVID-19 educational future to encourage informed predictions grounded on an ethics of possibilities.3 They considered, among others, how COVID-19 offers opportunities beyond the development of new digital pedagogies and they call for a rethink of the purpose of education to harness more democratic and just societies.

A citizenry with historical knowledge and memory of pandemics would arguably be better able to manage a pandemic than a citizenry with scant historical knowledge. To mitigate COVID-19 infections, countries are resorting to strategies to "flatten the curve", which involves reducing the number of new cases from one day to the next. Strategies such as the imposition of lockdowns, social distancing, sanitising and quarantine, are being employed to achieve this: all common practices learnt from past pandemics. Flattening the curve can prevent healthcare systems from becoming overwhelmed,4 but alone, it cannot terminate the pandemic. Lamentably, Dr Anthony Fauci, Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, recently announced that a COVID-19 vaccine could take 12-18 months to be approved for public use.5 COVID-19 does not only encourage scientific research in virology, it may also influence the future school curriculum, as was the case with the HIV and AIDS pandemic.

This article is an exploratory proposal aimed at integrating historical knowledge of pandemics into the History curriculum at schools. For practical reasons, it proposes the integration of historical pandemics into the grades 7-9 Social Science History curriculum. History teaching at school is informed by the South African National Curriculum Statement, Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (NCS CAPS), which is not a static and inflexible document to be followed slavishly. It allows teachers to align their learning content with the contextual needs of their learners. For example, the NCS states that one of its aims is to ensure that children acquire and apply knowledge and skills in ways that are meaningful to their own lives.6 In this regard, the curriculum promotes knowledge in local contexts, while being sensitive to global imperatives.7 In particular, the NCS highlights concepts associated with historical inquiry, such as an appreciation for the past and the forces that shaped it; as well as the dialectical relations between cause and effect, change and continuity, and time and chronology.

Historical consciousness, as an integral part of History teaching, refers to an awareness of how matters past, present and future, relate to one another in a way that enables the individual to create a specific kind of meaning in relation to history.8 In light of COVID-19, it would be legitimate for contemporary History teachers to question, for instance, why is there a lacuna in historical consciousness and public memory of the 1918 Spanish Flu, given its scale and similarities with COVID-19, and why teaching about the two world wars of the 20th century is virtually synonymous with History as a subject, but knowledge of an event that decimated the lives of hundreds of thousands of ordinary people, is not mentioned? Teacher education institutions cannot ignore these questions, especially in view of recent university protests, when students demanded curriculum reform that is relevant and meaningful to their lives.9

Poor historical consciousness of the 1918 Spanish Flu is a contested issue in the literature and of direct concern to the 21st-century critical historian. If a lack of consciousness of a significant historical experience can be used as evidence of an omission in the current curriculum, then historians and teachers would want to take corrective action and learn from past oversights. But historiography is informed by underlying interests, and the critical historian would not want memory and lessons learnt from COVID-19 to fade and be forgotten, as in the case of the 1918 Spanish Flu. The purpose of this proposal is therefore to argue for the inclusion of historical knowledge of pandemics to become part of school History. Bernstein's pedagogical device (explained later) is offered to frame the integration process. As a guide towards the selection of historical knowledge of pandemics, what follows is a review of the literature relevant to historical inquiry into past pandemics.

Historical references to earlier pandemics

This section deals with prominent historical references that may be relevant as sources of curriculum-related literature. The literature deals with issues regarding the arguably poor historical consciousness of pandemics, as expressed in a work by Howard Phillips,10 which is the main source of knowledge on the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic in South Africa. This section offers a composite view of the history of worldwide pandemics between the 16th and 19th centuries, before ending with a discussion of the "Leit Motiv" model of historical enquiry into pandemics.11 As a frame of reference, the History teacher may be guided by the "Leit Motiv" model by drawing on learners' lived experiences of COVID-19.

It is quite ironic that despite poor historical consciousness of the 1918 Spanish Flu, there seems to be a modest selection of literature to design a curriculum proposal. In the age of electronic communication and the internet, references to literature on the 1918 Spanish Flu are easily accessible. For example, Martin Kettle, a journalist, wrote a piece in the Guardian remembering the 100th anniversary of the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic which killed about 100 million people (a contested number, contrary to footnote 1) - which caused more deaths than the first and second world wars combined.12 Controversially, Kettle further suggests that perhaps the Spanish Flu faded from memory because a disease has no victor to celebrate, while wars have victors. While Kettle's explanation resonates with the popular adage that history is written by the victor(s), it is an over-simplification of history from a disciplinary perspective. The same question regarding fading memories about the 1918 Spanish Flu was treated in an academically plausible way by Phillips, a leading scholar of the 1918 Spanish Flu in South Africa.13 Phillips' doctoral study is arguably one of the first that traced the course of the epidemic in five main areas where it severely paralysed everyday life, namely the Witwatersrand gold mines, Cape Town, Bloemfontein, Kimberley and the Transkei.14

Phillips argues that the Spanish Flu of 1918 is one of the worst-known natural disasters, with little place in history or living memory. He further postulates that its obscurity in the national archive and memory may be ascribed to multiple reasons, ranging from its ephemeral nature to issues of historiography. First, Phillips asserts that the Spanish Flu was short lived (1918/19) rather than protracted; second, that it coincided with the Armistice that ended the First World War (1914-1918) which commanded public attention at a global level; and third, that the 1918 pandemic being referred to as a 'flu' and not a 'plague' perhaps inadvertently diminished its gravity as an epoch-making event.15 But, more importantly, the question as to why historians failed to give sustainable attention to the 1918 pandemic and prevent its fading from popular memory, may be because they were interested in political and economic issues, to the exclusion of a social history. A social history privileges the conditions and interests of the masses and primarily exposes the power relations that shape society.16Mainstream historians were primarily preoccupied with nationalism, race relations, capitalist development and the class struggle, which left little room for day-to-day matters such as how people lived or died.17

A very popular but exceptional South African reference to the 1918 Spanish Flu is the website of St John's College, Johannesburg. In a recent update on its Spanish Flu history, the College connected its institutional memory thereof with contemporary experiences of COVID-19. The website reveals:18

... that the present suspension of school activities, imposed by the Covid-19 crisis, is not unprecedented in the history of St John's College as 102 years ago, the College went through times probably more challenging than these confronting the school now. Then, too, a pandemic necessitated the school's closure for a prolonged period. Then, they did not have the blessing (or the curse?) of electronic communications and so were unable to continue teaching activities during the hiatus, and the entire term's work had to be crammed into five weeks, when schools were eventually allowed to reopen.

The website refers to thought-provoking news segments from the school's newsletter on the 1918 Spanish Flu and recalls critical moments and events such as the death of some teachers, which create a vivid recollection of the school's sombre climate at that time. Teachers and learners at St John's may have an enhanced historical consciousness of the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic which will enrich their understanding of past pandemics and determine how they connect with the present, especially COVID-19. They will be able, for instance, to identify the similarities and differences between the two pandemics in an academically meaningful way, which would be highly commendable from a history-teaching perspective.

The South African History Online (SAHO) site is another popular reference point for information on seminal South African historical events.19 Relying mainly on Phillips' work as an historical reference on the local experience of the 1918 Spanish Flu, SAHO traces its spread to South Africa via the ports of Durban and Cape Town. By the end of 1918, more than 127 000 black people and 11 000 whites had succumbed to the epidemic. In general, about 500 000 people died of the epidemic in South Africa, the fifth-hardest hit nation worldwide.20 For Africans the epidemic came after the hardships of the 1913 Land Act, war-time inflation, the droughts of 1914-1916 and the floods of 1916-1917. Unlike 102 years ago, when sea-travel was a popular mode of transport, the HINI virus spread gradually across the globe. With a 21st-century technologically advanced air-travel sector, COVID-19 is spreading like wildfire and has led to a ban on domestic and international travel to limit its devastation. Contrary to the spread of the 1918 Spanish Flu that came via sea travel, the first diagnosed cases of COVID-19 in South Africa were announced on 5 March 2020, emanating from the return of tourists by aeroplane from Italy (at that time, the epicentre of the pandemic).21 The first patient was a 38-year-old male who formed part of a group of ten people who had arrived back in South Africa on 1 March 2020.

The history of pandemics goes back to ancient times but, in modern history, the recording of influenza pandemics goes back to outbreaks which were recognised by their common clinical features.22 The first pandemic developed from a 1580 epidemic which spread from Europe to Asia and Africa. During the 17th century, influenza epidemics occurred across Europe. Three major influenza pandemics occurred in the 18th century and spread to North America, South America and most of Europe. Influenza pandemics occurred during 1830/31, 1833/34 and 1889/90, with little or no influenza activity worldwide between 1847/48 and the 1889/90 pandemic. Because the cause of pandemics was unknown at the time, flu epidemics were named according to their country of origin (e.g., the 1889/90 pandemic was called the Russian Flu). After reaching North America, the Russian Flu spread to Latin America and reached Asia in February. By March, the flu had become a pandemic in New Zealand and Australia. In the spring of 1890, the pandemic spread to Africa and Asia. The 1889/90 pandemic is the first for which detailed records are available. Influenza activity was relatively insignificant for the next two decades and many people regarded influenza as an episodic, mild respiratory infection until 1918, with the outbreak of the Spanish Flu.23

Notwithstanding historians' historiographical abandonment of the 1918 Spanish Flu and other pandemics, various related publications have appeared over the years. For example, the New York Times listed a few essential publications dealing with a range of pandemics in the past, now easily accessible.24 Such texts include Pox Americana - the Great Smallpox Epidemic of 1775-1782, by E A Fenn; The Fever: How Malaria has Ruled Humankind for 500,000 Years, by S Shah; Flu: The Story of the Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918 and the Search for the Virus that Caused It, by G Kolata and The Hot Zone - The Terrifying True Story of the Origin of the Ebola Virus, by K Preston.25

Of the few theoretical constructs of historical inquiry into epidemics and pandemics is the "Leit Motiv" model developed by Howard Markel,26who identified seven main themes from his historical investigation into epidemics and pandemics. Markel's model is explained to facilitate its recontexualisation, and as practical example to the History teacher how to use it as a pedagogical device in teaching the history of pandemics.

First, "[t]hinking about epidemics is almost always framed and shaped by how a given society understands a particular disease to travel and infect its victims". What Markel refers to here, is the availability of knowledge at the time of the pandemic. For example, in the absence of scientific knowledge, a pandemic may be ascribed to a 'curse from God' or a mythical event, etc. The response or treatment may be influenced by the knowledge that people have at the time. Second, "[t]he economic devastation typically associated with epidemics can have a strong influence on the public's response to a contagious disease crisis". With lockdown, for instance, comes a great cost to the economy and suffering at the social and individual level. Third, "[t]he movements of people and goods and the speed of travel are major factors in the spread of pandemic disease". Historically, the bubonic plagues coincided with ocean travel and imperial conquest, and the lesson that increased travel around the globe comes with risks will now be taken seriously after COVID-19. Attention to the development of transportation in relation to the spread of disease may be highlighted under this theme. Fourth, "[o]ur fascination with the suddenly appearing microbe that kills relatively few in spectacular fashion too often trumps our approach to infectious scourges that patiently kill millions every year". For example, in 2003, SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) affected approximately 8 000 people and killed 800 - which was much more dramatic than its response to tuberculosis, which infected 8 000 000 and killed 3 000 000 that same year.27 Fifth, "[w] idespread media coverage of epidemics is hardly new and is an essential part of any epidemic". For instance, the media have the power to shape the public's perception of an epidemic and with advanced technological media, news spread virtually in real-time. As teaching activities, the media coverage of pandemics can become research topics for learners. Learners will be given opportunities to engage with archival material to get a sense of historical research. Sixth, "[a] dangerous theme of epidemics past is the concealment of the problem from the world at large". Countries concealed news of an epidemic to protect economic assets and trade. A case in point: in 1892, the German government initially concealed that year's cholera pandemic because of fears that closing the port of Hamburg - at the time the largest port in the world - would mean economic ruin for many. Other examples are when concealment takes place motivated by nationalistic bias, pride or politics, as was the case with China during the first months of the SARS epidemic of 2003, and Indonesia and avian influenza. Lastly, "[o]ne of the saddest themes of epidemics throughout history has been the tendency to blame or scapegoat particular social groups". This is also true for COVID-19, for example when the American president, Donald Trump, called the disease a "Chinese virus"28 and when Africans in China faced eviction after being blamed for spreading COVID-19.29 Variations of the model will occur when applying it to any pandemic, as Markel demonstrated. Markel's model of historical inquiry provides a practical point of departure to the History teacher.

The focus of this article is on the integration of historical pandemics into the grades 7-9 Social Science NCS. The article is informed by the research question: how can historical knowledge of pandemics be integrated into the history curriculum? Bernstein's pedagogical device serves as a theoretical framework for conceptualising the integration of historical knowledge of pandemics as part of the History curriculum. A convenient sample of history teachers (N=15), enrolled for a History of Education honours module at the University of South Africa (Unisa) served as respondents to a set of questions probing their knowledge of historical pandemics and their views on its integration into the history curriculum. Respondents completed a set of online questions and returned them to the author via email. Following this introduction and brief literature discussion of pandemics as historical inquiry, the article unfolds by discussing Bernstein's pedagogical device to frame the integration of historical pandemics and the History curriculum. History teachers' responses to the questions are discussed in relation to Bernstein's framework. The article draws some conclusions and suggests recommendations for teacher education.

Bernstein's pedagogical device and the History curriculum

Bernstein's notion of the pedagogical device is employed in this article to integrate historical knowledge of pandemics into the Senior Phase History curriculum. Bernstein makes a distinction between what knowledge is relayed (the message) and an underlying pedagogic device that structures and organises the content and distribution of that knowledge.30 To this end, Bernstein identifies three main fields of the pedagogical device, namely knowledge production, recontexualisation and reproduction.31 In this proposal, the focus is on knowledge content selection by curriculum planners, the pedagogisation of the content as curriculum knowledge and texts, and the mediation of the curriculum at the classroom level. The focus is therefore on the recontextualising and reproduction fields. Bernstein thus places emphasis on an analysis of the production and reproduction of knowledge via official schooling institutions.

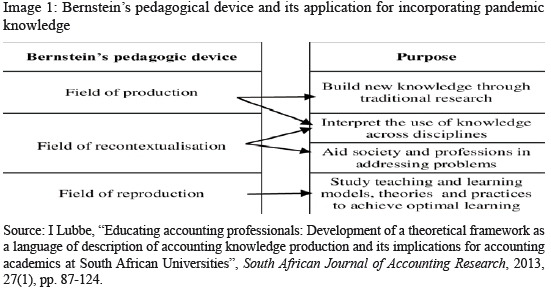

For the purpose of this article, the following simplified diagram (Image 1), borrowed from Lubbe, is useful for elucidating the relationship between Bernstein's pedagogical device and the generative learning practices that may emanate from such devices.

Curriculum conceptualisation and design do not take place in a vacuum. History teachers are invariably guided, first, by the curriculum policy that defines their educational aims, and, second, by the classification and disciplinary nature of the knowledge to be taught at an institutional level. According to the NCS's policy on History teaching, the subject is underpinned by strong empirical foundations involving inquiry, as well as analytical thinking and its application. The NCS defines the purpose of studying History as seeking to:32

... enable people to understand and evaluate how past human action has an impact on the present and how it influences the future. History is a process of enquiry and involves asking questions about the past: What happened? When did it happen? Why did it happen then? It is about how to think analytically about the stories people tell us about the past and how we internalise that information.

According to Bernstein's conceptual framework, the first field of pedagogical concern would be to determine the disciplinary nature of the knowledge intended to be integrated into the curriculum. In Bernstein's terms, the question is whether the historical study of pandemics can become a pedagogical discourse, identifiable by its own concepts and relationship to other disciplines.33 Bernstein distinguishes between every day and specialised knowledge, arguing that everyday knowledge is distinguished from the theoretical by the role each type of knowledge plays in society.34Bernstein differentiates between horizontal and vertical knowledge, to classify knowledge. Hoadley, referencing Bernstein, distinguishes between an elaborated code or a "school code", as opposed to common-sense knowledge of everyday life.35 In this article Bernstein's pedagogical device provides a framework to integrate historical knowledge of pandemics and History teaching.

Introducing knowledge of historical pandemics would require appropriate texts and teachers who can demonstrate deep conceptual understanding of the subject. For example, it may be expected from history teachers to display basic knowledge of for instance, COVID-19 as a sub-microscopic virus resorting under the discipline of virology. As a disease, it generatively intersects with a myriad of disciplines across the natural and social sciences. COVID-19, which is caused by the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, is an acute novel emerging infection.36 Taking the field of knowledge production as the first concern in Bernstein's pedagogical device, historical knowledge of pandemics and disease would become the context in which pandemics may be studied as a history theme. In terms of framing the history of pandemics as a specialist field, it will draw on the sub-discipline of epidemiology. Epidemiology has been defined as the study of the emergence, distribution and control of disease, disability and death among groups of people.37The field combines the sciences of biology, clinical medicine, sociology, mathematics and ecology, to understand patterns of health problems and improve human health across the globe. From a disciplinary perspective, the historian may primarily be attracted by the sociological and ecological dimensions of the pandemic. In a historical study of the 1918 Spanish Flu, historians would, for instance, be selective of the content with a focus on who (people), when (time), where (spatial), why(causal) and how (ecological/environmental) the pandemic affected human society.38

As a discipline, History is a specialised field which is capable of theorising new knowledge about COVID-19 and past pandemics. As a disciplinary classification, the history of pandemics would draw on segments of epidemiology, but as a sub-field which is integrated in the broader study of History. Its disciplinary definition would blur its boundaries with science, society and ethics. There would therefore not be a strong independent field, but an integration and interaction with related disciplines. While there may be multiple disciplinary overlaps between the study of pandemics and History, Bernstein's field of knowledge production is useful in conceptualising the field, its relations and interaction with other disciplines, and its potential sources of new knowledge.

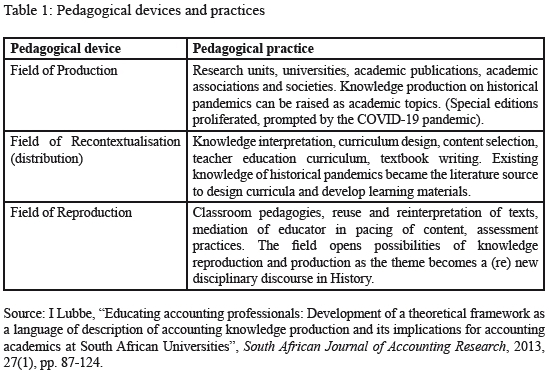

Considering the purpose of the pedagogical device, image 1 illustrates how the framework provides a heuristic to understand the field of knowledge production as different from the field of recontextualisation. Table 1 shows the capacity of the pedagogical device as a framework to describe knowledge production practices at institutional levels.

Bernstein's second field of knowledge recontextualisation describes how existing knowledge is ordered and disordered when knowledge selection is made and converted into a curriculum or a textbook. Recontextualisation involves the privileging of selected texts which manifest themselves as knowledge for school-going children. At this stage, the recontextualised knowledge no longer resembles the original because it has been pedagogised or converted into pedagogical discourses.39 Here, a potential pedagogical discourse of historical pandemics may be identifiable by a selection of emerging concepts and events in relation to other aspects of pandemics. Curriculum design and textbook writing take place during recontextualisation.

The field of knowledge reproduction predominates in primary, secondary and tertiary classrooms. In this space, the selected pedagogic texts created in the field of recontextualisation (e.g., curriculum knowledge and textbooks) are used by teachers preparing for classroom teaching. Teachers play the role of knowledge experts, and their content and pedagogical knowledge become crucial in determining the quality of the pedagogical discourse which, in this case, revolves around historical knowledge of pandemics. Needless to say, teachers with a high competence in pedagogy and content will relay the pedagogical discourse more effectively than those with mediocre levels of knowledge.

While image 1 (above) illuminates the relations between the pedagogical device and the various objectives, table 1 shows the generative pedagogical practices associated with each device.

What follows is a synthesis of the History teachers' responses, presented as an entry point for considering Bernstein's pedagogical device as a framework for the integration of the history of pandemics into the History curriculum.

History teachers' responses to pandemic historical knowledge and curriculum space

While the responses of teachers did not reveal significant knowledge of pandemics of the past, their responses are indicative of their main concerns during COVID-19. Their responses displayed a mixed knowledge response with potential to develop a disciplinary discourse on historical pandemics. Some teachers mentioned the 1918 Spanish Flu and the Smallpox epidemic, but concerns were mainly epidemiological in nature. The participants referred to the need to "define a pandemic" and "COVID-19" and needed an explanation for "what is it and where does it originate from".40 Since epidemiology studies the emergence, distribution and control of disease, disability and death among populations,41 the respondents were interested in knowing "the symptoms, treatment and which countries are affected". Epidemiology uses mathematical models and graphs to illustrate the distribution and mortality per population or geographical location. Epidemiology would be a primary knowledge source from which to derive the history of pandemics. However, while accurate knowledge of the disease and its treatment may be necessary, historically relevant content would be foregrounded. Pandemics would be viewed from a historical perspective in relation to society and ecology - the main disciplinary overlapping with epidemiology.

Secondly, respondents raised issues related to "mental health and coping mechanism[s] during the pandemic" - reactions which are mainly based on their subjective experiences during COVID-19. During the lockdown period, the greatest disruption was caused by the total closure of the national and global economies, which resulted in massive job losses and financial gloom in an already ailing economy in a recession. Psychological stress is associated with "unemployment and an uncertain future [which] causes fear and panic". Both knowledge production and distribution will be needed to link the psycho-social and health effects of a pandemic with historical knowledge. For instance, a significant consequence of the 1918 Spanish Flu was the establishment of the South African Department of Health, which did not exist prior to that.42

Thirdly, the respondents referred to "school closure and its disruptive effects" on society and the school curriculum. The educational theme offers an opportunity for knowledge production, as the education sector is ablaze with new pedagogies for "online teaching and home-schooling". Education and information technology have brought greater awareness of educational inequalities, with the privileged schooling sector being least disadvantaged during the lockdown. The respondents raised issues related to "skills, leadership and being prepared for future pandemics". Any educational responses will have implications for teacher education, as new skills and pedagogies are emerging from the conditions imposed by COVID-19. With historical pandemics as part of school knowledge, education is viewed as the intervention space to address the poor knowledge of past pandemics.

The NCS CAPS curriculum makes provision for one project in Social Sciences in the Senior Phase (grades 7, 8 and 9). It is recommended that the History project be assigned in either grade 8 or 9 learners, as they will have experience of project work from the previous grade. The project should be offered with the necessary support and monitoring, to ensure that the envisaged outcome is achieved. The project topic should be given at the beginning of the term, with regular periods for monitoring and feedback.43

The curriculum makes provision for an oral and a written section. The theme - "The history of pandemics" - corresponds with the CAPS requirement that a project address the teacher and learner contexts. CAPS requires that the research comprise at least 300 words and two illustrations, with captions. The oral section can be an interview report on a selected aspect of pandemics, e.g. an interview with an elderly person with memories/knowledge of the Spanish Flu of 1918 or oral reporting on previous pandemics. The interview/story should be around 600 words in length. The duration of the project may extend over a term, but its management is best left to the History teacher who will intersperse project work with lessons, feedback and learner presentations.

Conclusion and recommendations

This article explored how historical knowledge of pandemics can be integrated into the Senior Phase History CAPS curriculum, using Bernstein's pedagogical device as a framework (Refer to Table 1 above). In the production field, research activities aim at the production of new knowledge, while in the recontextualised field knowledge is applied in curriculum design and reproduced via pedagogical activities at teaching level. The following conclusions and recommendation are made to facilitate the teaching of the pandemics as historical knowledge.

First, based on the responses and existing literature on the history of pandemics, there seems to be potential for the emergence and construction of a specialised pedagogical discourse within the disciplinary boundaries of History. A rich archive of historical literature points to a budding, incubated set of underdeveloped themes which are ready to sprout into a new branch of historical knowledge. The responses of History teachers were overwhelmingly in favour that historical inquiry of pandemics should be integrated into the History curriculum. It is recommended that higher education institutions encourage research into the historical aspects of pandemics, to enrich the existing materials available for the purpose of curriculum usage.

Second, the demarcation of the field from its primary discipline, namely epidemiology, will have intersectional boundaries that will emphasise the historical, rather than the medical dimensions of pandemics. According to the definition of epidemiology, the primary overlap with History is in respect of sociology and ecology. A historical perspective on the pandemic as a socio-ecological phenomenon may potentially generate new research interest. However, at the level of curriculum design, education and training, existing knowledge will become the main source. In this regard, the literature mentioned in this article, for example, the Leit Motiv-model44for historical inquiry, provides concrete references to inform curriculum and pedagogical processes. This model, for example, identified common patterns in past pandemics useful to inform historical research. It is recommended that curriculum designers and teacher education institutions build on existing theoretical knowledge, to design a curriculum to teach historical knowledge of pandemics.

Third, with reference to the recontextualisation of knowledge, the responses of teachers can serve as a yardstick for gauging their knowledge level, interests and historical consciousness. Teacher education institutions are advised to consider the relatively undeveloped state of teachers' knowledge when designing the History curriculum.

Fourth, the recontextualisation and redistribution stages overlap, as teachers are expected to rework texts and materials for classroom use and lesson plans. Project-based teaching requires appropriate pedagogical intervention, and attention should be given to both written and oral forms of assessment. Teacher education should stimulate the production of new knowledge and the conversion of knowledge into a pedagogic discourse through effective teaching.45 Educational institutions are advised to consciously develop a historical pandemic discourse, integrated with History as a discipline.

In conclusion, to finally return to the research question: how can historical knowledge of pandemics be integrated with History teaching; this article has shown that there are sufficient grounds in the CAPS curriculum in the Senior Grade CAPS History section, for the history of pandemics to be taught in a History classroom. The article has also shown the generative potential of knowledge production and how knowledge can be converted during the recontextualisation phase, for the purpose of pedagogy. A flexible (rather than rigid) application of Bernstein's pedagogical device, comprising of three fields offers a framework for the development of a historical pandemic discourse and the mapping of a curriculum-integration proposal, from conception to implementation.46

1 It is estimated that during the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic (H1N1 virus) about 500 million people (one-third of the world's population) became infected. The number of deaths was estimated to be at least 50 million worldwide, with about 675 000 occurring in the United States. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918-pandemic-hlnl.html, as accessed on 8 June 2020.

2 It is necessary to explain the difference between an "epidemic" and a "pandemic". The following explanation is taken from "Major Epidemic and Pandemic Diseases": "A number of communicable diseases can constitute significant threats at local, regional or global levels leading to epidemics or pandemics. An epidemic refers to an increase, often sudden, in the number of cases of an infectious disease above what is normally expected in a given population in a specific area. Examples of major epidemics include cholera and diarrhoeal diseases, measles, malaria, and dengue fever. A pandemic is an epidemic of infectious disease that spreads through human populations across a large region, multiple continents or globally. These are diseases that infect humans and can spread easily. Pandemics become disasters when they cause large numbers of deaths, as well as illness, and/or have severe social and economic impacts". Available at https://media.ifrc.org/ifrc/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2018/11/12-EPIDEMIC-HR.pdf, as accessed on 12 June 2020.

3 MA Peters and F Rizvi, et al, "Reimagining the new pedagogical possibilities for universities post-COVID-19", Educational Philosophy and Theory, 2020, DOI: 10.1080/00131857.2020.1777655 (available at https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1777655, as accessed on 29 June 2020.

4 Johns Hopkins University, "New Cases of COVID-19 in World Countries", Johns Hopkins University, USA (available at https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/new-cases, as accessed on 27 May 2020.

5 ME Garciaa-Ojeda, "Dr Fauci's belief that we'll have a COVID-19 vaccine in 18 months is optimistic - but not improbable", The Conversation, 13 May 2020.

6 DBE, Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) (Pretoria, Government Printing Works, 2012).

7 DBE, Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) (Pretoria, Government Printing Works, 2012), p. 10.

8 LJ King, "What is black historical consciousness", A Clark, Contemplating historical consciousness: Notes from the field (Berghalm Books, New York, 2019), pp. 163-174.

9 During 2015/16 #FeesMustFall student protests, South African university students across the country demanded a relevant and decolonised curriculum. Higher education institutions consequently amended their curriculum transformation policies to be sensitive to students' demands.

10 H Phillips, "'Black October': The impact of the Spanish Influenza Epidemic of 1918 on South Africa", Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, 1984, University of Cape Town.

11 H Markel, "Contemplating pandemics: The role of historical inquiry in developing pandemic-mitigating strategies for the 21 century" (available at https://bioethicsarchive.georgetown.edu/pcsbi/sites/default/files/Markel%20Meeting%2020%20Presentation.pdf, as accessed on 11 June 2020).

12 M Kettle, The Guardian, "A century on, why are we forgetting the death of 100 Million"? (available at https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/may/25/spanish-flu-pandemic-1918-forgetting-100-million-deaths, as accessed on 4 June 2020).

13 H Phillips, "'Black October': (Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, 1984, University of Cape Town), pp. 1-9.

14 H Phillips, "'Black October': (Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, 1984, University of Cape Town), p. vii.

15 H Phillips, "'Black October': (Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, 1984, University of Cape Town), p. 449.

16 H Phillips, "'Black October': (Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, 1984, University of Cape Town), p. 450.

17 H Phillips, "'Black October': (Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, 1984, University of Cape Town), pp. 1-9.

18 Anon., St John's College, "Johannesburg and the Spanish Flu of 1918" (available at file:///C:/Users/davidsno/Downloads/St%20John's%20College,%20Johannesburg,%20and%20the%20Spanish%20flu%20of%201918%20%2 0%20The%20Heritage%20Portal.html, as accessed on 6 June 2020).

19 Anon., South African History Online, "The Influenza Epidemic" (available at https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/influenza-epidemic, as accessed on 6 June 2020).

20 Anon., St John's College, "Johannesburg and the Spanish Flu of 1918" (available at file:///C:/Users/davidsno/Downloads/St%20John's%20College,%20Johannesburg,%20and%20the%20Spanish%20flu%20of%201918%20%2 0%20The%20Heritage%20Portal.html, as accessed on 6 June 2020).

21 National Institute of Communicable Diseases, "First Case of COVID-19 Reported in South Africa" (available at https://www.nicd.ac.za/first-case-of-covid-19-coronavirus-reported-in-sa/, as accessed on 8 June 2020).

22 BA Cunha, "Influenza: Historical aspects of epidemics and pandemics" (Elsevier Inc., Amsterdam, 2004), pp. 141-155.

23 BA Cunha, "Influenza: The Spanish Flu did not originate in Spain, but the USA (Elsevier Inc., Amsterdam, 2004), pp. 141-155.

24 Anon., New York Times, "7 Essential Books about Pandemics" (available at https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/24/books/pandemic-books-coronavirus.html, as accessed on 6 June 2020).

25 New York Times, "7 Essential Books about Pandemics", 24 February 2020.

26 H Markel, "Contemplating pandemics: The role of historical inquiry in developing pandemic-mitigating strategies for the 21 century", SM Lemon, MA Hamburg, P Frederick et al., Ethical and legal considerations in mitigating pandemic disease, Workshop summary, free download, 2007 (available at http://www.nap.edu/catalogue/11917, as accessed on 25 May 2020), pp. 1-30.

27 H Markel, "Contemplating pandemics: SM Lemon, MA Hamburg, P Frederick et al., Ethical and legal considerations in mitigating pandemic disease, Workshop summary, free download, 2007 (available at http://www.nap.edu/catalogue/11917, as accessed on 25 May 2020), pp. 1-30.

28 D Scott, "Trump's New Fixation on using a Racist Name for the Coronavirus", 18 March 2020 (available at https://www.vox.com/2020/3/18/21185478/coronavirus-usa-trump-chinese-virus, as accessed on 11 June 2020).

29 OkayAfrica, "Africans in China being Evicted from Homes and Blamed for Spreading the Coronavirus" (available at https://www.okayafrica.com/africans-in-china-guangzhou-evicted-left-homeless-blamed-for-coronavirus, as accessed on 11 June 2020).

30 C Bertram, "Bernstein's theory of the pedagogic device as a frame to study History Curriculum Reform in South Africa", Yesterday & Today, 7, 2012, pp. 1-11.

31 P Singh, "Pedagogical knowledge: Bernstein's theory of the pedagogical device", British Journal of Sociology of Education, 23(4), 2002, pp. 571-582.

32 DBE, Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) (Pretoria, Government Printing Works, 2012).

33 U Hoadley, "Analysing Pedagogy: The Problem of Framing", 2006 (available at http://www.cilt.uct.ac.za/sites/default/files/image_tool/images/104/hoadley2006.pdf, as accessed on 8 June 2020).

34 LM Wheelehan, "The pedagogic device: The relevance of Bernstein's analysis for VET", 2005.

35 U Hoadley, "Analysing Pedagogy: 2006 (available at http://www.cilt.uct.ac.za/sites/default/files/image_tool/images/104/hoadley2006.pdf, as accessed on 8 June 2020). p. 2.

36 UNESDOC, "Statement on COVID-19: Ethical Considerations from a Global Perspective" (available at https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373115, as accessed on 6 June 2020).

37 T Childers, "What is epidemiology?", Live Science Contributor, 5 March 2020 (available at https://www.livescience.com/epidemiology.html, as accessed on 8 June 2020).

38 DBE, Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) (Pretoria, Government Printing Works, 2012).

39 P Singh, "Pedagogical knowledge: British Journal of Sociology of Education, 23(4), 2002, pp. 571-582.

40 "Respondents" in this section refers to what was taken from the online respondents' reflections. Themes were developed by clustering common responses into categories which were regrouped into themes. The initial six themes were reduced to four, when "prevention" and "education" became one and "psycho" and "socioeconomic" became "psycho-social".

41 T Childers, "What is epidemiology?", Live Science Contributor, 5 March 2020 (available at https://www.livescience.com/epidemiology.html, as accessed on 8 June 2020).

42 H Phillips, "'Black October': (Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, 1984, University of Cape Town), p. 374.

43 DBE, Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) (Pretoria, Government Printing Works, 2012).

44 H Markel, "Contemplating pandemics: SM Lemon, MA Hamburg, P Frederick et al., Ethical and legal considerations..., Workshop summary, free download, 2007 (available at http://www.nap.edu/catalogue/11917, as accessed on 25 May 2020), pp. 1-30.

45 I Lubbe, "Educating accounting professionals: South African Journal of Accounting Research, 2013, 27(1), pp.87-124.

46 The author is indebted to the reviewers for their valuable critique which improved the final outcome of this article.