Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Yesterday and Today

On-line version ISSN 2309-9003

Print version ISSN 2223-0386

Y&T n.23 Vanderbijlpark Jul. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2223-0386/2020/n23a3

ARTICLES

Learn History, think unity: National integration through History education in Cameroon, 1961-2018

Roland Ndille

University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa; roland.ndille-ntongwe@wits.ac.za; ORCID No.: orcid.org/0000-0001-7105-8515

ABSTRACT

Since independence, one of the greatest worries of African states has been how to maintain national cohesion amongst the multiplicity of ethnic groups which characterize them. My aim in this paper is to show that, other factors notwithstanding, national integration had been a major educational ideology in Cameroon and that it contributed to the peace and stability that the country was known for, amidst a turbulent central African region until the advent of neoliberalism and multiparty politics in 1990. I discuss the nature of contents that helped to achieve this while arguing that a de-emphasis on the social sciences and particularly on the integrationist approach to history education in the multiparty era is not unconnected to the post-1990 reinvention of various parochial identities antithetic to national cohesion in which recent calls for the secession of the Anglophone region by some radical groups is seen as the culmination of the trend. I conclude by highlighting the social relevance of curriculum within which history education should be re-invented as a vector for peace, unity and national integration in the country.

Keywords: History Curriculum; National Integration; National Unity; Peaceful Co-existence; Cameroon History.

Introduction

We task ourselves to create an exemplary republic united in its diversity to carry the country to emergence... . Such a republic will be achieved through a harmonious community spirit... . In this effort, our education is highly implicated (Paul Biya, paraphrased from MINJEC 2015:1,28).

Recently, I was involved in a UNESCO Africa Regional Conference on the governance of cultural diversities. Reflecting on the theme, one thing was clear; until the November 2016 Anglophone teachers and lawyers strike who's poor handling orchestrated a secessionist movement in the Anglophone regions, Cameroon had enjoyed relative stability and national cohesion, making it a continental reference point for peaceful coexistence. In fact before 2016, apart from the political tensions that marked the return to multi-party democracy in the early 1990s, the country had not experienced any incidents that threatened national unity and integrity since independence in 1960-1961. Finding the magic wand used to hold its diverse population together has been a puzzle to many. More than twenty years before, Nyamnjoh (1998:1) had engaged in the task of answering a similar question; "what keeps Cameroon together despite widespread instability in Africa; despite the turbulence of the sub-regional environment in which it finds itself; and despite its own internal contradictions?" His answers included what he termed government's "packages aimed at deflating the disaffected; its propensity to vacillate on most issues of collective interest, and an infinite ability to develop survival strategies".

While the above answers find credence especially within the context of Africa's return to democracy in the early 1990s, research in history education demonstrates that in the majority of cases, frantic efforts to maintain national unity could be attributed to concrete educational policies and strategies employed by states in the governance of diversities (Peshkin, 1967; Clignet, 1975; Wang, 1978, Akpan, 1990; Ndlovu, 2009; Kohl, 2010; Egbefo 2014; Njeng'ere, 2014). Within this theme, research on Cameroon is to say the least, unavailable- a fact from which the current engagement draws value.1 I argue that the attainment of national cohesion in Cameroon especially in the first three decades of independence has been an important educational ideology of the state. I also argue that the gradual neglect of this policy from the 1990s has produced crisis outcomes. By way of structure, I start by establishing the cultural diversity of Cameroon which necessitated an integrationist history curriculum. Next I discuss the nature of history contents and how it facilitated the attainment of the goal of national unity. In the third and last section I show how government's de-emphasis on a unity-in-diversity history curriculum after 1990 has accounted, at least in part, for various crisis of co-existence which continue to rock the country.

I found the historical research method most appropriate for this paper; the purpose being to enable the readers gain a clearer and accurate picture of the continuities and changes in the relationship between history education and the promotion of values of national unity in Cameroon. Stakeholders in this field would appreciate the epistemological meanings that both the evidence and their analysis make and find clear premises for the solution of current problems. This is an ubiquitous goal of historical research. Besides this, the adoption of historical research rationalizes the triangulation of my emic experiences [as learner, teacher and researcher of history education in Cameroon] with archival data, history textbooks and interviews as resources used to establish this account. The textbooks, syllabuses and schemes-of-work used in this study were/are officially prescribed for the school system in Cameroon within the period under review or parts of it. The resource persons were purposefully sampled with the common denominator being their varying experiences in history education in the country.

Cameroon's diversities: The rationale for national integration

The fact that African countries are cast by moulds of colonial conquest rather than by pre-colonial indigenous characteristics cannot be overemphasized. People possessing distinctive languages, religions and cultures living as homogenous groups within well-defined geographical, linguistic and cultural precincts were coerced into larger poly-ethnic, cultural and linguistic administrative units called colonies. The territory that became Cameroon was settled at different points of history by various waves of Bantu ethnic groups that occupied the coastal and forest zones spanning the centre, east, south, littoral and south west regions of the country. From the middle belt to the northern tip were settled a variety of Sudano-Bantu, Peul and Arabic speaking people. In the northwest and western parts of the country people consisting of Tikar and Chamba groups locally referred to as Semi-Bantu arrived there between the 17th and 18thcenturies. The ethnic groups total over 260; their languages, innumerable and in most cases 'mutually unintelligible' (Neba, 1999:91).

The migratory and settlement patterns in Cameroon are associated with parallel differences in political and social organization. While in some parts there are monarchical and theocratic authoritative highly centralized states, others exhibit republican characteristics of consensual government through smaller village councils of elders (Ngoh 1996). The majority of the north is Muslim, the south, Christian and a greater part of these still adhere to a variety of indigenous belief systems. The country's geographical location at the crossroads where west meets central Africa and where the tropical forest zone in the south fades into the Sudan in the north also implies natural diversities which have shaped cultural and economic practices.

Besides the above, Cameroon's triple colonial heritage; from the German protectorate (1884-1916) followed by separate British and French mandates and trusteeships (1916-1960-1) add to their subsequent reunification in 1961 to make it a unique case in Africa which was bound to complicate the life of any government. Amadou Ahidjo the pioneer president (1960-1982) once described the country as "an original puzzle of living diversities [which]... often left contradictory imprints on the ways in which Cameroonians think and act" (Ahidjo, 1968a:26).

An appreciation of Cameroons diversity is therefore essential to the understanding of the state's emphasis on "a harmonious living together" as current rhetoric puts it. Certain patterns indigenous to most ethnic, colonial and regional cultures have often emphasized social and political cleavages that seem to serve as oppositions between one group and another and breed resistance to incorporation into larger political entities. This has been the most popular justification for the majority of the crisis of conviviality (Vubo, 2006:135) and upheavals in African states (Mbaku 2018) which in extreme cases have threatened state survival (Kymlicka, 1996). The need to mitigate such crises and in turn meet the aspirations of a majority of the citizens became a central feature of the problematic of the nation building process in Africa and rationalized policies of national identity. As Ahidjo, emphasized:

Every nation is composed of a mosaic of families, tendencies and interests. But a nation is not great, nor even viable, until these various elements complement each other and combine together in a constructive manner.... [In view of this] we are determined to purge our nation of every consideration, every factor likely, directly or indirectly, to cement and foster differences. National Unity means that in the work-yard of national construction, there is neither Ewondo nor Douala, Bamileke nor Boulou, Foulbe nor Bassa. We are, one and all, simply Cameroonians (Ahidjo, 1962a:3; 1962b:1).

In fact, as a political ideology in Cameroon, national integration was expected to go beyond an "awareness of a common identity amongst Cameroonians to an actual manifestation of a national community life that is conscious of, respects and preserves the supreme-ness of the state. It also requires that each citizen should respect and give a chance to other Cameroonians, region, ethnic group or colonial identity notwithstanding as their right of being Cameroons, uphold the general interest and strive for the common good (MINJES, 2015:2). This can be achieved from two directions; adoption by individuals or imposition by the state' (Wang, 1978:464). Adoption involves the level of subjective identification of individuals with the nation (value consensus) and imposition speaks to the initiatives of labelling by some central authority (Elad, 1983:60) through national symbols, the constitution and educational policies.

It is important to mention that, imposition may not necessarily be coercive. However, there are those, as in Machiavelli's Prince who believe that coercive measures could also be used if the attainment of the goal of national unity is at stake. As Van de Berghel (1965) has argued, where value consensus doesn't form the basis of integration, a combination of political coercion, compliance or regulation must prevail for the interest of state survival. In fact particularly for post-independent multi-ethnic African states, he argues that the differences between various group identities are so fundamental that they betray the notion of value consensus. That is, the possibility of voluntary adoption of integrative values by the different parochial identities is difficult to be achieved without enforcement and automatically imposes the structural necessity for government action. This places the responsibility for national cohesion on the state which may sometimes be seen as having coercive or propaganda interpretations.

Enhancing national integration in Cameroon through History education

As mentioned above, the relationship between education and national integration has been found to be significant. Studies agree that the increase in the level of national identification among citizens and at the same time the diminishing ethnocentrism correlates positively with increasing levels of educational attainment as well as the quality and type of education given (Elad 1982:1). In Nigeria for instance, Alan Peshkin's 1967 study shows how despite the recognition of profound cultural disparities in the country, education policies at independence hardly reflected genuine concerns for unity. While Onyemelukwe-Waziri (2017) links this policy deficiency to the escalation of the secessionist Biafra war (1967-70), Akpan (1990:2943-4) shows how immediately after the war there were talks on how education could be used effectively to mitigate disintegration as the war had attempted to do. Answers included a national basis curriculum for primary and secondary schools, a well-diversified student recruitment system and an efficient staff exchange programme for the universities.

Similar results of the (non)promotion of national integration through the educational system have been found in Njeng'ere's 2014 study of Kenya, Poormina's (2018) and Raman's (2008) study of India as well as Wang's (1978) study of Malaysia. Wang for instance shows that education was actually found to have contributed significantly in blurring ethnic lines in two ways; (1) structurally, most occupational or economic categories had a good mix of ethnic groups and (2) politically, through the curriculum people displayed a high sense of national citizenship and loyalty to the nation. Njeng'ere's (2014) research also showed significantly positive relationships between education and the development of social capital in Kenya as individuals exhibited the propensity to trust, to be tolerant, develop shared values and respect state institutions. However, as he argued, the de-emphasis of such a curriculum in Kenya accounts for a fall in the values of national integration as some recent post-electoral ethnic clashes demonstrated.

As far as Cameroon is concerned, research is limited. Nyamnjoh's study mentioned above makes little or no reference to the role of education while Ngwoh's 2017 paper alludes to the teaching of civics and citizenship education. On her part Elad's 1983 study besides not including the curriculum, recognizes government's purposeful application of the education for national integration policy in the country. She maintained that:

Prior to independence and reunification people had internalized different terminal as well as instrumental values. This was bound to show a variation in their respective allegiances to the political centre. In the long run however, with a policy of education which encouraged acceptance of national norms and ideologies many inter-cultural differences were lessened and particularistic and local values were gradually replaced by attitudes more consonant with the needs of the whole nation; [unity in diversity] (Elad, 1982:6).

While Elad may have used her variable of educational structure and language policy to make this conclusion, the definition of education as (1) the imparting of knowledge and skills and most importantly (2) the inculcation in the clientele of the national value systems of a given society (Tambo, 2003a:4-7) speak to the role of specific school contents in achieving national integration. In fact research beyond Cameroon (Ajor and Odey 2018; Ndlovu 2009; Raman 2008) has placed history at the centre of the national integration objective of attaining "a citizenry for an enlightened social order; and the amalgamation of subpopulations hitherto fragmented by colonial, religious, linguistic, or ethnic differences" (Peshkin 1967:323).

How then was the policy of national integration implemented through history education in Cameroon? We must recall that the present Republic of Cameroon is a 1961 merger (reunification) of the former British administered Southern Cameroons and la Republique du Cameroun (the former French administered Cameroon which had gained independence on January 1, 1960). The colonial curriculum experiences that the British and French spheres brought to the reunification table were incongruous as both colonial curricula were dictated by their respective colonial ideologies. For the British Southern Cameroons, contents were dominated by the History of Britain, the rest of Europe and a few topics in Africa and Nigerian History. Very little of the history of British Cameroons was taught in both the primary and secondary schools (Ndille, 2012; 2018). Likewise in French Cameroon there was a strict observance of the French nationalist history curriculum (White 1996). This type of curricula emanating from the two colonial spheres caste long shadows on the national integration project of the independent and reunified state and thus needed to be revised. Government actually presented an un-harmonized educational system as causing political setbacks in its march towards national unity and capped curriculum reform ".. .as a way of being faithful to our values of knowing how to live with one another" (Ahidjo 1980:36).

A series of laws were thus passed and commissions were set up between 1963 and 1971 to enforce the policy of harmonization and prepare national school curricula (Nwana 2000:10-21; Ndille, 2018). Particularly for the subject history, there was quite a good deal of semblance between the two subsystems following such efforts (Ngum 2012). Contents used in this paper to advance the discussion therefore apply to both subsystems (English and French) and levels (primary and secondary) where such instruction is said to have prevailed. In 1963, national goals for teaching history pointed to the fact that:

Historical knowledge should acquaint the pupils with various aspects of national life, give them insight into the historical and cultural background of Cameroon as a nation and instil patriotism in them. History should bring to focus the realization that we all have a common heritage as this will strengthen the sense of unity (West Cameroon 1963).

It is from such goals that national oriented contents were proposed. As far as curriculum development in concerned in Cameroon, it is the tendency for government to outline the contents of subject syllabuses and prescribe textbooks for use in schools. Subject associations at national, regional and divisional levels further break down syllabuses into teachable units; defining their objectives, suggesting teaching strategies, proposing teacher and learner activities and resources. Such schemes-of-work become handy for teachers to prepare their lessons. This top-down approach to curriculum development is still in place today. The analysis of the nature of historical contents and how they addressed the national integration ideology is drawn from such documents and validated by the interview data authors emic experiences as mentioned above. Gham (2015) has analysed the politics of textbook writing, selection and the teaching of history in Cameroon in which he agrees with Ngum (2012) that variations in publication and authorship notwithstanding, the content remains the same as specified by the curriculum policy for all sub-systems of education.

Mention must also me made of the degree to which one may assume that the Cameroon history curriculum was national in terms of the volume of contents reflecting a national character as opposed to other contents (Ndille, 2012). Despite two syllabus reviews for primary schools (1963, 1968) world history contents continued to outweigh local/national history until a 2001 review turned the tides. Similarly for secondary schools, curriculum for the junior levels (Forms one and two) is until now, more of European than Cameroon and African history. For the intermediate and senior classes (forms 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7), the contents are dictated by the examination boards which undertook revisions in 1997 giving priority (about 40%) to Cameroon History. Consequently, our discussion of national integration as a principle in the Cameroon history curriculum doesn't imply that Cameroon is a good example of states which have successfully nationalized/indigenized or Africanized their history curriculum. I simply draw on topics and contents that address goals of national integration and how they are presented to the learners.

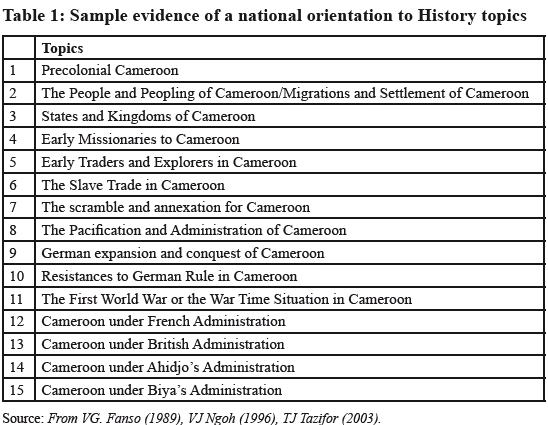

To begin, the first thing easily noticed in history education in Cameroon in the use of the name Cameroon in almost every topic regarding the country. This is done even when an aspect or issue addresses only a limited scope within the country. Local names are downplayed for the national. Such an approach in topic presentation is seen on Table 1.

From the titling of the lesson topics on Table 1, one can see a conscious attempt to follow a historiographical tradition that imposes a structure on the past that never was. As a political entity, Cameroon only emerged in July 1884 following the German annexation of the people around the Wouri River. Despite the fact that the Wouri estuary had been referred to as Rio dos Cameroes by the Portuguese in 1471 and subsequently by the Dutch, Spanish, English, French and Germans, it didn't take a national character until the pacification of the territory and the establishment of the first maps of German Cameroon in the 1900. This notwithstanding, developments in any part of the territory before the German annexation are given a national character in history lessons. Early European Missionaries, traders and explorers mentioned in the lessons only saw themselves as having arrived and worked in specific places like Douala, Bimbia and Victoria rather than people who had come to a territorial space called Cameroon. However, the picture that was presented to learners all around the country is that such people worked in their national territory.

Apart from the above, the various people presented in the 18th and 19thcentury migrations and settlements only became part of a common territorial space after the German annexed the area. These had included the Tikars and Chamba migrations, the Bantu Migrations in the Southern/coastal areas and the Sudano/Arabic in the north. While each of these categories was composed of smaller clan groups, they were all presented in history lessons as Cameroonians settling in different parts of the territory. Even after the dissolution of the German Cameroon colonial entity following their defeat in the First World War and the British and French Partition, the title; British or French administration of Cameroon as it appears in the textbooks and syllabuses does not give the learners the impression that each of these was only concerned with part of the territory. The names British Southern Cameroons and French Cameroons are downplayed in favour of an all-inclusive Cameroon for the sake of imparting in the learners the idea of a single sovereign state.

Pierre Bourdieu has argued that from inception, the state, as it was at independence and reunification in Cameroon, assumes the character of an X to be determined which successfully claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical and symbolic violence over a definite territory and over the totality of the corresponding population. Being able to exert symbolic violence means incarnating itself in objectivity in the form of specific organizational structures and mechanisms (such as education and the curriculum) and in subjectivity in the form of mental structures, categories, perceptions and thoughts (Bourdieu, 1994:3-4). Bourdieu implies that the state not only rationally establishes institutions and structures but skews the goals of education, curriculum contents and the way they are approached to give the citizens a particular perception of reality. This includes thinking the state even where and when the state didn't exist. This is what he terms the state 'realizing itself in social structures and in mental structures adapted to the learners (Bourdieu 1994:4). When this is done, he concludes, 'the instituted institution makes us forget that it issued out a long series of acts of the institution (in the active sense) and hence has all the appearances of the natural (Bourdieu, 1994:4).

Applied to the knowledge of history in Cameroon, by giving a national orientation to all contents including issues of local histories, learners in Cameroon were made to have an image of a country which spreads as far back as it can be imagined. Seeing themselves as Cameroonians they identify with contents from all parts of the country. A sense of national belonging is inspired as problems pertaining to particular parts of the country are seen in historical contexts as national problems involving every one; regional, location or ethnic affiliation notwithstanding. This approach to historiographical development in Cameroon could be said to be idealistic; presenting the world/country as the state feels/wants it to be seen rather than how it was. In South Africa for example topics are context specific. One can appreciate clearly a topic such as the Dutch interactions with the San and Khoi at the Cape rather than an ideal national character of European contacts with a South Africa which, at the time, never was. In Cameroon, it is the reverse; Cameroon on the Eve of German Colonization when the contents simply dwell on the interactions between the coastal Douala and Bimbia on one hand and the German, British and French Traders on the other which at the time did not involve all those who belong to the state of Cameroon today.

As MINES (2015) has noted, the idea of Cameroon as a unified group of people from diverse provenance has been sustained throughout Cameroon history from the first European contacts to precolonial internal developments to the treaties of German annexation and from the petitions of partition addressed to the League of Nations by different ethnic groups to the naming of political parties in both French and British Cameroon. In fact even the treaty presented in Cameroon textbooks as the treaty of annexation of Cameroon, was actually a treaty between German traders and the Douala people on the Atlantic coast. Textbooks presented no treaty between for example the Fulbe in the north or the Tikar groups in the North-western parts of the country (other than a blood pact between the explorer Zingtraff and the Bali leader Galega I) nor a general treaty to make the cession of sovereignty of the entire people to the Germans a national matter. Cameroonians of all regions through the approach to history contents were meant to see themselves in the Germano-Duala Treaty even if their fore-fathers never knew what happened in Douala in 1884 and didn't identify with it when they became aware of such a development.

According to Mbiatat (2019), the approach of a national, elitist and political history as it was prior to the 1990s was to espouse the idea that ethnic groups have had part of a common territorial space called Cameroon for a long time and no one has greater right over another. It was also to reflect the notion of peaceful coexistence as a long standing characteristic among the people of Cameroon. Diverse cultures were viewed as a common heritage to which all Cameroonians must become proud of; a positive strength to be enhanced for the growth of the nation. This approach was to hammer home the message of intercultural harmony, a symbiotic living together which emphasises survival as a result of good neighbourliness (Etuge, 2019).

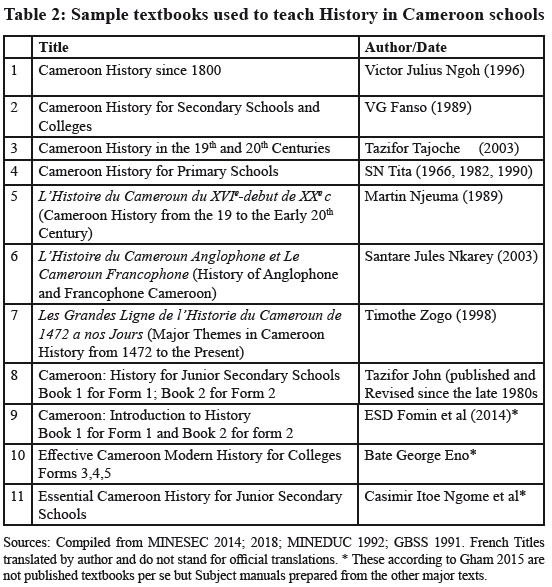

Apart from precolonial developments, Colonialism featured prominently in the nationalist history curriculum. Colonial developments such as the establishment of a few kilometres of railway or a bridge over an area were presented as national benefits while experiences of suffering and exploitation of particular groups of people were seen as episodes of national pain which retarded development (Abbas 2019). Meanwhile textbooks qualified resistance movements as national and their failures were accounted for by the absence of collaboration or the inability of ethnic groups to establish a national resistant front (Ngoh 1996; Tazifor 2003). The 1916 partition of the erstwhile German Cameroon was presented as a dark point in the history of the nation while the 1961 reunification of British and former French Cameroons was presented as a milestone to regain their once lost grand Cameroonian identity (Lukong 2019). Pictures of the Foumban conference which galvanized the process of reunification were often on show in the textbooks with the captions "how nice it is to meet our brothers" (Ngoh 1987). This ideology has not only been used in contents presentation as described above but in textbook titles as would be seen in Table 2.

As noted above, the official history curriculum in Cameroon for all levels; primary, secondary and university as well as types of schools; grammar, commercial, technical, comprehensive and other specialized programmes includes a blend of Cameroon, Africa and world history. In University history departments it also includes some theoretical and methodological courses. It is interesting to note that some of the textbook writers cover all the contents suggested for the class in one book with one title. For instance, while the contents of the national history curriculum of secondary schools forms one and two and most of class 4 and five of the primary schools had less than thirty percent Cameroon history contents, the title of Tita's and Tazifor's books for example (see Table 2), insinuate that the content is on Cameroon. It would be surprising to learn that a majority of the contents in these books include chapters as dispersed as ancient Greece and Rome; ancient China, Japan and India, Islam and the Empires of Western Sudan. Apart from that, whether the contents address specific ethnicities at a time when Cameroon had not become a polity, the textbook authors have had a tendency to give their titles a national orientation. For instance, Fanso's Book 1 and Martin Njeuma's textbook are predominantly on precolonial times while Zogo talks of a Cameroon History since 1472; when there was no entity like Cameroon.

This perspective is not by chance. It is meant to highlight in the learners the fact that the Cameroon identity is as old as history; that it has taken ages to solidify and that youths have a challenge to honour, promote and sustain it (Tabe, 2019; MINJES, 2015:28). According to Jason (1985:12), terms such as regions, ethnic groups, tribes, clans and villages used to describe people and historical developments in Africa have been seen to be highly charged and skilfully manipulating. It was feared (and evidence has proven) that ethnicities and other identities that make up the state would one day attempt to create a nation in their own image. In Africa, therefore, the state as in the largest political entity that people recognize, is the least politically charged and therefore the best term to describe the people and represent historical heritage. Consequently, nation builders in Cameroon argued strongly that particularistic definitions of people and history may breed hatred between them and that the best way to kill this is to move from such narrow a presentation of contents to a more national outlook (Etuge 2019).

In a study of the textbooks in Cameroon, Fru and Wassermann (2017) have argued that textbooks incorporate certain attitudes and ways of looking at the world. Particular opinions and interpretations are presented as Jason has expressed above. Ngalim (2014) asserts that the vision of the country reflects the organization of curricula and for Cameroon the multicultural nature of the country has since independence occasioned the curriculum politics of unity and national integration. This expresses the need for all Cameroonians to feel and live as one and to have a common destination. A curriculum policy which makes Cameroonians perceive themselves in this light was to serve as the enabling environment for national unity (Ngongang, 2019; Epitime 2019). If examined within this premise therefore, textbooks, are certainly excellent resources with which to analyse social and historical consciousness (Fru and Wassermann 2019). To a greater extent, this was significantly achieved in Cameroon until recently.

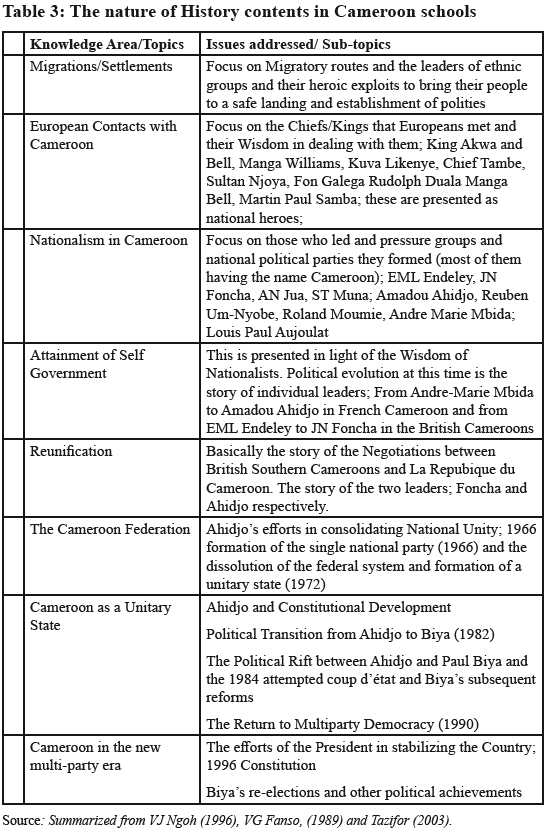

Apart from inculcating the Cameroon national identity in the Cameroonian learners, history education also focused essentially on giving a national political orientation to the history of independent Cameroon. By focusing on teaching the efforts of the president and the top political class of the country in nation building, post-independent historiography and by implication history education not only became nationalistic but essentially elitist and political. Crawford (2000) explains that, the nature of states in general not only required that people see themselves as part of one national ancestry but also to identify with the agency that originated and sustained that identity. It was therefore necessary for history to not only be national in orientation but also elitist and political. This helped to conglomerate all voices and ideologies unto the state and its political leadership. Table 3 presents a summary of the political/elitist approach to history contents.

Table 3 reveals that the history curriculum in Cameroon, at least for the first three decades, was elitist and political. Very little attention was drawn to the economic and social history of the country. Even when socioeconomic life of the country featured as a topic, it was presented as an achievement of the political leadership of the time (Etuge, 2019). Most Cameroonian students only met other genres of history at the university. What they brought with them from secondary school was the national political history of the country alongside other foreign contents. Apart from making history predominantly political, historical contents were presented as a conscious effort in nation building towards which all citizens had to ally. In the history of the former British administered sphere (Southern Cameroons) historical agents who advocated reunification with former French Cameroon are viewed as heroes of history while advocates of the unsuccessful option of integration with Nigeria are often unrepresented in public memory. Where balanced judgement requires that they feature, very little is mentioned about them (Ngongang, 2019).

In most of the Cameroon history lessons, reunification was presented as the best political decision that Cameroonians ever made. A unified Cameroon was made to imply better opportunities for all its citizens (Mbiatat, 2019) and a seeming advantage (at least language wise) over other Africans that school children were called to exploit. Like reunification, other sensitive areas of history such as the 1966 merger of all political parties and the 1972 May 20 referendum whose implementation has of recent been highly criticised, were simply presented to the learners as positive moves for the interest of a greater and prosperous Cameroon. While many held the position that such moves were calculated steps by Ahidjo to establish a personality cult (Lukong, 2019), textbooks in use in the classrooms downplayed any part which would distract the youth from forging respect for national leadership, state symbols and an integrationist attitude (Epitime, 2019). Rather than being viewed as the destruction of the parliamentary democracy which the two spheres of Cameroon had each entered the union with, the establishment of the single national party; Grand Partie Unifie on September 1, 1966 was presented as a move "to reduce the political infighting which had characterised pre-1966 political activity in Cameroon." "Such an atmosphere," learners read, "was not healthy for national unity which needed all the energies that Cameroonian nationalists dispensed in arguing against one another" (Tita, 1990; Ngoh, 1987:257).

In the September 1966 event, the president of the republic was presented in history lessons as the "father of the nation.who in his usual generosity," was coming "towards the warring factions of West Cameroon and volunteered to dissolve his large and well established party, the Union Camerounais (UC) so that we may together build up a stable country united and equal with no advantage or privilege to anyone big or small" (Etangondop, 2004). In the same light, the dissolution of the federal system in 1972 was presented in school lessons as:

... the peaceful revolution; as government's genuine effort especially that of the president to limit expenditure and preserve the resources initially spent on duplicating functions through federal institutions to enhance development.... A young nation like Cameroon required a united action in terms ofplanning policies to achieve progress (Fonkeng 2007:193).

The establishment of a unitary state was also presented as the failure and unworkability of the federal system since the state of West Cameroon continued to experience financial difficulties despite federal government balancing of its subsidy totalling more than three quarters of its budget annually (Ngoh, 2004).

All in all, the rationale for a curriculum approach emphasizing national unity and integration is manifold but the point to emphasize here is that, such an approach guaranteed state stability, peace, social harmony and respect for state institutions as could be seen in pre-1990 Cameroon. It made it difficult for the learners, even as they grew from children to youth and adults to unnecessarily impede state action or see fellow Cameroonians as strange bedfellows. Learners saw history as an evolution of the process of nation building and development (Ngongang 2009).

Curriculum development had therefore taken the form of "reproducing the society" which the leadership sought to build (Ndlovu, 2009:68) and for history, justified the development of nationalist political historiographies. As Ogot (1978:72) puts it, such were born out of the perceived role that historical learning was to play in the newly independent states.

Generally in Cameroon, a certain feeling of nostalgia for the years 1960-1980s has hardly waned. The phrase "in those day" is often used to look back at these years where peace and stability prevailed; years in which people from the south served in the northern-most parts of the country without fear of being tagged gadamayo or when those from the northwest lived amongst the coastal people without been seen as come-no-go2These years were also characterised by sustained economic growth, investments in national infrastructural development, a generalized adherence to the state structure and its symbols, peace and unity amongst Cameroonians. There was an attempted coup d'etat in 1984 but generally until 1990s, no overt threats to national cohesion marked the history of the country. While the autocratic nature of Amadou Ahidjo's one party state (inherited by Paul Biya in 1982) may have played a significant role in attaining these goals by neutralizing dissidents (Joseph 1980), consciously established policies in the social domain such as a curriculum approach highlighting the essence of national unity and citizens adherence to national symbols as seen above, cannot be underestimated.

In fact it is possible to surmise that the impact of a nationally based history education programme was very high until the 1990s. As Mbiatat (2019) attests, "contents derived from such goals created 'a pleasant attitude for emotional unity and essential integrity among the children of the nation." Epitime (2019) also agrees that the kind of history they learnt in their days (1970s and 1980s) made them to see one another first as Cameroonians before their ethnic or regional origins. This, according to her, has been the major reason why Cameroonian parents began downplaying the various ethnic and cultural practices such as forbidding inter-ethnic marriages. Evidence has also shown that where a curriculum for national integration was not implemented, little was achieved (Peshkin, 1967; Akpan, 1990; Ajor and Odey 2018:71).

De-emphasis on the National Integration Orientation of History education and its Consequences

It must be mentioned that the degree and level of national integration and state cohesion in a country can be measured in many spheres of life. This includes the extent of ethnic and cultural mix in work spaces and regions of the country characterised by a harmonious living together; a high level of tolerance for different ethnicities and alternative social and political affiliations; sustained peaceful co-existence; limited ethnic/ regional/political clashes and the respect for state authority. It is also characterised by a shift in individual and group loyalties and a look towards a new centre, whose institutions possess or demand jurisdiction over preexisting parochial identities and easily obtain such without unnecessary coercion. Evidence of the contrary as in the recurrent Christian-Muslim/ northerner-southerner clashes and the 1967-70 Biafran war in Nigeria, the post-electoral ethnic clashes in Kenya, the civil wars in the Central African Republic, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Sierra Leone and South Sudan as well as the current Anglophone crisis in Cameroon, to cite but these, could attest to the abating of the spirit of national cohesion in favour of some sort of sub-national identities within the state.

From the 1990s onwards, Cameroon has experienced several crises of coexistence which in part can account for some northern youths joining the Boko Haram quest for an Islamic state on parts of the Cameroon national territory since 2013 and a secessionist movement in the Anglophone regions of Cameroon since 2016. The reasons for such developments may be many and varied but certainly includes shifts in government policies after 1990 which de-emphasized the role of the school in fostering and sustaining national cohesion. The 1990s marked the end of the cold war and the adoption of neoliberalism as a global indication of openness and reform. This came with its own pressures on African nations. For Cameroon it required the reintroduction of multiparty democracy and the adoption of the Structural Adjustment Programme in the economic and socio-political domains.

In response to these developments, the enabling laws of 19 December 1990 (Cameroon 1990) led to the sprawling of micro and competing sub-nationalisms; regional/ethnic based political parties, regional elite associations, private press with various political leanings as well as patronising, tribalism, partisanship, discrimination, unequal distribution of resources and divide and rule (Nyamnjoh, 1998; Ngwoh 2017:1 Easyelimo 2019; Nkwi 2006; Vubo 2006). In the heavily cosmopolitan coastal cities and towns, issues of indigene and stranger re-emerged alongside mutual suspicion and open clashes (Nkwi, 2006; Vubo, 2006). Neoliberalism therefore contributed to the resurgence of the identity question and the politics of fragmentation as "the gradual unravelling of identities based on political ideology and culture" became characteristic of everyday life. There grew "a radical questioning and discrediting of the very basis of the erstwhile models of nation states" (Vubo, 2005:1) which had been characterised by streamlining efforts of governments but which had helped to sustain unity amongst the people.

In addition to the above, neoliberalism also inspired new orientations in economic and social policy which affected education and the role of the school as a vector for national integration. It emphasised human capital formation which to the advocates was an urgent demand of the new knowledge economy (World Bank, 2005). As part of the response of the education department, a National Education Forum was held in Yaoundé in 1995 and a new educational policy was enacted into law in 1998. This saw goals of education being revised in favour of a local and global rather than a national orientation to curriculum. Social sciences in general was de-emphasized to the advantage of sciences, technology and mathematics. This implied limited time allocations for social sciences and a revision of the contents. As the 1998 law stated emphasis was henceforth to be on "training citizens firmly rooted in their various cultures but open to the world... cultivating a love of effort and work well done; developing creativity and the spirit of enterprise, guaranteeing the right without discrimination to gender, political, religious opinion, social, cultural, linguistic and geographic origin' (Cameroon 1998).

As Tambo later observed, this new orientation of education was more of a desire to meet the demands of structural adjustment of the funding agencies and friendly governments (2003b:35) than of the national realities especially at that time when the country was soaked in political crisis and needed to rather emphasize the role of history and other social science subjects in building national integrity and solidarity. The neoliberal approach to education rather placed premium on human capital formation rather than the development of social capital (World Bank 2005). The development of a single national culture espoused by the Ahidjo regime (1961-1982) in the history curriculum was pushed aside. The new six years primary school course (until then it was 7 years) reduced emphasis on history by limiting its study to three years (previously it was four years). The new approach places premium on local history which is predominantly the history of ethnic groupings in Cameroon (Cameroon 2001). The consequence of this trend is a comparatively reduced knowledge of national history and sometimes a biased or skewed appreciation of the efforts of the state authorities and institutions as historical agents. These added to freedom of press, social media and the general socio-economic hardship has led to a high critic of government action rather than support and increased ethnic, colonial linguistic, regional, cultural heritage consciousness and political rivalry to the detriment of a harmonious living together.

Conclusion

In the paper, I have drawn from primary literature and some oral sources to demonstrate historically, the relationship between history education and national integration in Cameroon. I have pointed out that a major challenge for most African countries at independence was how to derive common values from the values of the diverse communities which characterised their polities. I have shown that for Cameroon values like national integration and peaceful coexistence were sustained through the teaching of nationalist history between 1961 and the early 1990s. I have also shown that the post 1990 turbulence in the country culminating crisis such as the Boko Haram in the north and the Anglophone crisis show are evidences of "a dearth in values of national cohesion "(Mbiatat, 2019). While bearing in mind the multiplicity of causal judgments in history, changes in educational goals and curriculum orientation away from national cohesion certainly account (to a large extent) to such a deficiency. Although the concept of a "one and indivisible Cameroon" continues to be a priority of government policy, various vices of subnational awareness have dug very deep in the fabrics of Cameroon's society to the point where mere rhetoric as is the case contemporaneously would hardly bring the train back to its rails if not accompanied by a revision of school curriculum and by implication history education.

Education policy developers therefore need a rethink of the orientation of history education for a country with a multiplicity of heritages as Cameroon. This will encourage social justice, equity, tolerance and compromise. Such an emphasis on history has shown positive results in early decades of independence and would evidently continue to do so in Cameroon if re-engaged. It must be mentioned that critics of this approach to history education may not find rational in its implementation. They may also see such a curriculum approach as propaganda. This notwithstanding, evidence has shown that an integrationist history curriculum discourages vices that imping on multi-cultural co-existence and enforces and reinforce virtues of social acceptance, promote shared attitudes and rejuvenates historical memories which in many respects have proven to guarantee peace and harmony in the face of divergences and multiplicities.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the UNESCO Africa Regional Office (Abuja) for my participation in the UNESCO Conference on the Governance of Cultural Diversities in Africa (Accra-September 2019) in which I presented on the topic The Rejected Stones are the Corner Stones: Educational Building Blocks to National Integration in Cameroon which inspired the current study. I am grateful to the participants at that Conference for their comments. I also thank the anonymous peer reviewers, proof-readers and the journal editor for their input(s) on this paper.

References

Ahidjo, A 1962a. Speech delivered by Amadou Ahidjo, at the Congress of the Union Camerounaise, Ebolowa, 4-8 July 1962. National Archives-Yaounde. [ Links ]

Ahidjo, A 1962b. Address by Amadou Ahidjo, President of the Federal Republic of Cameroon to the Legislative Assembly. Yaounde 6th May 1962. National Archives Yaounde. [ Links ]

Ahidjo, A 1968. The political philosophy of Amadou Ahidjo. Political bureau of the Cameroon National Union. Paris: Paul Bory Publishers. [ Links ]

Ahidjo, A 1980. General Policy Report Presented by the National President of the Cameroon National Union, President of the United Republic of Cameroon. Baffoussam, 13 February 1980. National Archives Yaounde. [ Links ]

Ajor, J and Odey, J 2018. History: The epicentre of national integration. Lawati: A Journal of Contemporary Research 15(4):71-85. [ Links ]

Akpan, P 1990. The role of higher education in National integration in Nigeria. Higher Education 19(0):293-305. Available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/158727. Accessed on 28 October 2019. [ Links ]

Bourdieu, P, Wacquant, L and Farage, S 1994. Rethinking the state: Genesis and structure of the Bureaucratic Field. Sociological Theory 12(1):1-18. Available at URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/202032. Accessed on 10 November 2019. [ Links ]

Cameroon 1990. 95/53 of 19 December 1990 Relating to Freedom of Association and Assembly. Yaounde: National Assembly. [ Links ]

Cameroon 1998. Law No. 98/004 of 14 April 1998. To laydown guidelines for Education in Cameroon. Yaoundé: SOPECAM. [ Links ]

Cameroon 2001. National Syllabuses for Anglophone Primary Schools. Yaounde: Ministry of Basic Education. [ Links ]

Clignet, R 1975. The Search for National Integration in Africa. New York: The Free Press [ Links ]

Easyelimu 2019. National Integration. High School Notes for Form 1 in Kenya. Available at https://www.easyelimu.com/high-school-notes/history/form1/item631. Accessed on 2 November 2019. [ Links ]

Crawford, K 2000. Researching the ideological and political role of the History textbook: Issues and methods. International Journal of History Learning, Teaching and Research 1(1): 1-8. Available at https://www.doi.org/1018546/HERJ.01.01.07. Accessed on 25 September 2019. [ Links ]

Ebune, J 2019. Personal interview with; University Professor, Aged 64, 22 July 2019. [ Links ]

Egbefo, D 2014. History: A Panacea for National Integration and Sustainable Democracy in Nigeria. Historical Research Letter 13(0):1-11. Available at https://www.doi.org/10.11.861.9012. Accessed on 4 October 2019. [ Links ]

Elad, MG 1982. Schooling and national integration in Cameroon. Doctor of Philosophy Thesis, Institute of Education, University of London. [ Links ]

Epitime, R 2019. Personal interview with; Retired School Teacher-Kumba; aged 75. Interviewed in Kumba, July 09, 2019 [ Links ]

Etangondop M 2004. Federalism in a one-party state. In: VJ Ngoh, (Ed.). Cameroon: From a Federal to a Unitary State, 1961-1972. A critical study, pp. 108-42. Limbe: Design House. [ Links ]

Etuge, J 2019. Personal interview with; University Professor, Aged 55, Nkong-samba, 2 August 2019. [ Links ]

Fonkeng, GE 2007. The History of Education in Cameroon, 1844-2004. Lewiston, NY, Queenston, Ontario, Canada, Lampeter, Ceredigion, Wales: The Edwin Mellen Press. [ Links ]

Fru, N and Wassermann, J 2017. Historical Knowledge-Genre as It relates to Reunification of Cameroon in Selected Anglophone Cameroonian History Textbooks. Yesterday & Today 18(0):42-63. Available at https://www.doi.org/10.17159/2223-0386/n18a3. Accessed on 4 October 2019. [ Links ]

GBSS. 1991. Government Bilingual Secondary School Kumba: Book List for the 1991/92 Academic Year. Personal Collection. [ Links ]

Gham, G 2015. The varied nature of historical textbooks in the teaching of History in Cameroon. Yesterday&Today 14(0):267-76. [ Links ]

Habbas, H 2019. Personal interview with; Retired Inspector of Education-Garoua II, aged 70, Douala, 3 August 2019. [ Links ]

Jason, C 1985. Nation, tribe and ethnic group in Africa. Cultural survival Quarterly Magazine. September 1985. [ Links ]

Kale, K (ed.), 1980. An African experiment in nation building: The bilingual republic of Cameroon since reunification. Colorado: Westview Press. [ Links ]

Kohl, C 2010. National integration in Guinea Bissau since independence. Cadernos de Estudos Africanos. 20(0):86-112. Available at https://www.doi.org/10.4000/cea.155. Accessed on 4 October 2019. [ Links ]

Kymlicka, W 1996. Three forms of group differentiated citizenship. In: Benhabib, Seyla (ed). Democracy and difference: Contesting the boundaries of the political. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press. 153-170. [ Links ]

Lukong, N 2019. Personal interview with; Secondary School Teacher, aged 50. Buea, 23 July 2019. [ Links ]

Maduike, K 2018. Routing ethnic violence in a divided city: Walking in the footsteps of armed mobs in Jos, Nigeria. Journal of Modern African studies. 58(3):443-470. [ Links ]

Mbaku, J 2018. Constitutions, citizens and challenges of national integration and nation building in Africa. International and Comparative Law Review. 18(1):7-50. Available at http://www.doi.org/10.2478/iclr-2018-0025. Accessed on 18 January 2019. [ Links ]

Mbiatat, Z 2019. Personal interview with; Retired School Head-teacher, aged 80. Kumba 10 July 2019. [ Links ]

MINEDUC. 1992. Ministry of National Education: Recommended Textbooks for the Year 1992/1993. National Archives Buea. [ Links ]

MINESEC. 2014. Ministry of Secondary Education: Official Book list for the 2014/15 Academic Year. Yaoundé: MINESEC [ Links ]

MINESEC. 2018. Ministry of Secondary Education: List of Approved School Textbooks for the 2018/19 Academic Year. Yaoundé: MINESEC [ Links ]

MINJES. 2015. Ministry of Youth Affairs and Civic Education: Cameroons National Integration Strategy. Yaoundé: MINJES [ Links ]

Ndille, R 2012. Towards the indigenization of the History Curriculum in Cameroon 18842001: Implications for the shift in paradigm to African historiography 1884-2001 in Peace and Security for African Development. Pretoria: Africa Institute of South Africa (AISA), 132-159. [ Links ]

Ndille, R 2018. Our schools, our identity: Efforts and challenges in the transformation of the History Curriculum in Cameroon. Yesterday and Today 20(2):91-123. Available at https://www.doi.org/10.17159/2223-0386/2018/n19a5. Accessed on 18 January 2019. [ Links ]

Ndlovu, M 2009. History Curriculum, nation building and the promotion of common values in Africa: A comaprative analysis of Zimbabwe and South Africa. Yesterday & Today, 4(0):67-77. [ Links ]

Ndongko, T and Nyamnjoh, F 2000. The Cameroon General Certificate of Education Board. In: Ndongko, T and Tambo, L (eds). Educational development in Cameroon 1961-1999. Platville, MD: Nkemnji Global Tech. 246-57. [ Links ]

Neba, A 1999. Modern geography of the Republic of Cameroon (3nd Ed). Bamenda: Neba Publishers. [ Links ]

Ngalame, E 2019a. Personal interview with; retired Secondary school History Teacher, aged 86. Tole-Buea, 23 July 2019. [ Links ]

Ngalame, E 2019b. National integration, a legacy of Cameroons reunification. Eden Newspaper, 6 November 2019. Available at https://www.edennewspaper.net/national-integration. Accessed 2 November 2019. [ Links ]

Ngalim, V 2014. Harmonization of educational subsystems of Cameroon: A multi perspective for democratic education. Creative Education 5(5):332-356. Available at https://www.doi.org.10.4236/ce.2014.55043. Accessed 12 October 2019. [ Links ]

Ngange, K and Kashim, T (eds) 2019. The Anglophone lawyers and teachers strikes in Cameroon (2016-2017). Yaoundé: les Press Universitaires de Yaounde. [ Links ]

Ngoh, V-J 2004. Cameroon: From a Federal to a Unitary State, 1961-1972. A critical study, 108-142. Limbe: Design House. [ Links ]

Ngoh, V-J 1987. Cameroon 1884-1985: A hundred years of history. Limbe: Navi-Group. [ Links ]

Ngoh, V-J 1996. History of Cameroon since 1800. Limbe: Presprint. [ Links ]

Ngongang, I 2019. Personal interview with; Teacher at Ecole Public Buea and graduate of History and Education (Masters) University of Buea. Also a chief Warrant officer of the Cameroon Defence Forces. Interviewed in Douala August 3 2019 [ Links ]

Ngum, H 2012. A comparative analysis of the harmonization of contents in primary school history between the Anglophone and Francophone subsystems of education. Unpublished long essay, Department of History, University of Buea. [ Links ]

Ngwoh, V 2017. An evaluation of nation building policies in Cameroon since colonial times. Afro-Asian Journal of Social Sciences 3(2):1-23. [ Links ]

Njeng'ere, D 2014. The role of curriculum in fostering national cohesion and integration: Opportunities and challenges. International Bureau of Education (IBE) Working Papers on Curriculum Issues No.11. Geneva: UNESCO. [ Links ]

Nkwi, W 2006. Elites, ethno-regional competition and the South West Elites Association (SWELA), 1991-1997. African Studies Monograph. 27(3):123-143. [ Links ]

Nyamnjoh, F 1998. Cameroon: A country united by ethnic ambition and difference. African Affairs, 98(0):101-118. [ Links ]

Ogot, B 1978. African Historiography From Colonial History to UNESCO's General History of Africa. In: Ogot, B (ed), UNESCO General History of Africa Volume 5. Paris: UNESCO. [ Links ]

Onyemelukwe-Waziri, H 2017. Impact of two wars on the educational system in Nigeria. Master of Arts Thesis, Clark University. [ Links ]

Peshkin, A 1967. Education and national integration in Nigeria. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 5(3):323-34. [ Links ]

Poormina, BK 2018. What is the role of education in national integration?. Seminar paper, REVA University. [ Links ]

Raman, S 2008. Curriculum materials for national integration in Malaysia: Match or Mismatch? Asia-Pacific Journal of Education 17(2):7-18. Available at https://www.doi.org.10.1080/02188799708547758. Accessed on 8 September 2019. [ Links ]

Tabe, S 2019. Personal interview with; Inspector of Education Mamfe, aged 58. Kumba, 10 July 2019. [ Links ]

Tambo, L 2000. Strategic concerns in curriculum development in Cameroon. In: Ndongko, T and Tambo, L (eds). Educational development in Cameroon 1961-1999. Platville, MD: Nkemnji Global Tech.152-66. [ Links ]

Tambo, L 2003a. Principles and methods of teaching: Applications in Cameroon schools. Buea: ANUCAM. [ Links ]

Tambo, L 2003b. Cameroon National Education Policy since the 1995 Forum. Limbe: Design House. [ Links ]

Tazifor, T 2003. Cameroon History in the 19th and 20th centuries. Buea: Educational Books Centre. [ Links ]

Tita, SN 1990. History of Cameroon Schools Book 3 for Class 7 (3rd Edition) Limbe: Nooremac Press. [ Links ]

Transparency International. 2011. Corruption Perception Index for Cameroon for 2011 Available at https://www.transparencyinternational.org/cpi2011-Cameroon Accessed on 10 September 2019. [ Links ]

Van den Berghel 1965. Africa: Social problems and change and conflict, SanFrancisco: Chandler. [ Links ]

Vubo, Emmanuel. 2006. Management of ethnic diversity in Cameroon against a backdrop of social crisis. Cahiers d'EtudesAfricaines. 181(1):135-156. [ Links ]

Vubo, E, Konings, P and Nyamnjoh, F 2005. Negotiating an Anglophone identity. A study of the politics of recognition in Cameroon. Cahiers d'Etudes Africaines 177(1):1-4. [ Links ]

Wang Chang, B-L 1978. Educational reforms for national integration: The west Malaysian experience. Camparative Education Review 22(3):464-479. [ Links ]

West Cameroon 1963. Educational policy of the federated state of West Cameroon. Buea: Government Printers. [ Links ]

White, B 1996. Talk about school: Education and the colonial project in British and French Africa 1860-1960. Comparative Education. 32(1):9-25. [ Links ]

World Bank 2005. Expanding opportunities and building competencies for young people: A new agenda for secondary education. Washington DC: World Bank. [ Links ]

1 In the UNESCO Africa Regional Conference on the Governance of Cultural Diversities (Accra, September 2019), I examined in general the educational building blocks for national unity in Cameroon as a whole for which history education was a subsection of how the state used the curriculum to maintain peaceful coexistence. The current paper is thus an effort to detail how history as a subject served national integration goals. The discussion here is limited to basic and secondary education.

2 Gadamayo is a term used in the northern parts of Cameroon to refer to Southerners (literarily meaning people coming from across the Mayo River locally assumed to be marking the southern fringes of the northern polities. On the other hand Come-no-go is used in the coastal areas (predominantly in the Southwest region) to refer to people from the Northwest region literarily meaning permanent settlers). While there has been a significant mix of Cameroons populations as far back as the colonial days, these terms have been popularized (and derogatorily to) with the advent of multiparty politics of the 1990s and its effects; one of which is the fading of national harmony.