Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Yesterday and Today

versión On-line ISSN 2309-9003

versión impresa ISSN 2223-0386

Y&T no.22 Vanderbijlpark 2019

HANDS-ON ARTICLE

An exploration of the shifts in imagined academic and civic identities across four history curriculum documents

Kirstin Kukard

Herzlia High School, Cape Town kirstinkukard@gmail.com ORCID No: 0000-0001-6473-7405

ABSTRACT

This article analyses four curriculum documents in terms of the kinds of academic and civic identities that they would seek to produce. The curriculum documents are two South African (Curriculum 2005 [1997] and the Curriculum and Policy Statement [2011]) and two English (the first History National Curriculum [1991] and the most recent Secondary History National Curriculum [2014]). The theoretical underpinnings of the discussion of identity are Bernstein's concepts of instructional and regulative discourse. The shifts in overall purpose and identity within the two contexts are striking. The first English national curriculum saw a tension between a focus on developing history learners who had a strong sense of national identity and using constructivist models that teach the learners the knowledge base of the subject. By contrast, Curriculum 2005 focused on attempting to create learners who were actively engaged with the problems of their current-day situation. By the second English national curriculum, a focus on making connections to current-day challenges had been introduced in addition to the existing concerns about national identity and understanding the way in which historians work. The Curriculum and Policy Statement (CAPS) reform in South Africa expressed greater concerns for developing historical thinking, but nevertheless retained a focus on actively engaged citizenship. The findings of this research provide a lens through which to consider current history curriculum reform and in particular, the ways in which curriculum documents imagine the learners that they would want to produce as both historians and citizens.

Keywords: Identity; Curriculum; Bernstein; Ministerial Task Team.

Introduction

This article draws on my Master's thesis,1 which examined the shifts in the way that four secondary history curriculum documents (National Curricula in England [1991; 2014] and in South Africa [1997; 2011]) imagined both the academic and civic identities of learners, particularly in relation to the purpose of school history. Given the current deliberation about revising the South African curriculum in light of the Ministerial Task Team's Report of February 2018, it is important to consider the ways in which the decisions made about the content of curricula are shaped by the implicit or explicit vision of the ideal history learner and citizen which the curriculum would like to produce. The research aimed to provide a way to describe the curriculum documents accurately through the development of a fine-grained analytic framework. Although my thesis considered both explicit and implicit civic identities, the purpose of this article is to focus on the three elements of the academic identities which relate to implied civic identities in the four curriculum documents. These findings are then related to the Ministerial Task Team Report.

This article begins by briefly describing the process of curriculum reform in each country. Bernstein's concept of pedagogic discourse is used to describe the ways in which the content choices of four history curriculum documents reflect differing imagined identities. The Ministerial Task Team report's recommendations regarding the curriculum content are considered.

Context of Curriculum Reform

England

History education in Britain went through a period of major revision from the 1970s, influenced by the progressive approaches of the Schools Council History Project (SCHP). This "new history" approach was seen as privileging skills over content and was linked to valuing learner-centred, constructivist approaches (Bertram, 2008:157). The first English National Curriculum came into place in the early 1990s at the behest of Margaret Thatcher. Thatcher was opposed to the 'new history' approaches because for her history was simply an "account of what happened in the past" and the most important function of the school curriculum was for learners to obtain a "knowledge of events" (Thatcher, 2013:573). Despite this, the History Working Group that was set up to produce the curriculum generally favoured the 'new history' approaches.

In 2013, after a series of revisions (1995; 1999; 2007), a radically new draft of the history national curriculum was tabled. The Conservative Education Minister, Michael Gove, made public statements arguing for the need for learners to have "a better understanding of the linear narrative of British history and Britain's impact on the world and the world's impact on Britain" (Gove in Vasagar, 2011). In pursuing his goal of "rigour", Gove's new history curriculum became dense and almost entirely British-focused. There was considerable backlash from historians, history educationalists and teachers, and the final draft of the history curriculum resembled the 2007 national curriculum much more closely than the 2013 draft had done (Counsell, 2014).

South Africa

The history curriculum under the apartheid regime encouraged "traditional" teaching practices based on the ideas of Afrikaner nationalist historians (Witz & Hamilton, 1991:29). "People's education" in the 1980s challenged this approach; this movement was heavily influenced by the Schools Council History Project and emphasised the importance of historical thinking. However, in the post-apartheid settlement, the focus on education as providing "portability of qualifications" (Ensor, 2003:326) led to the establishment of a fully integrated, outcomes-based curriculum. In this curriculum, history became part of the integrated Social Sciences, which incorporated Geography and Citizenship. While the review of Curriculum 2005 in 1999 resulted in history being reintroduced as a discrete subject, the underlying approach of outcomes-based education remained. A further revision began in 2009. The review committee argued for a clearly specified curriculum, which resulted in the CAPS curriculum (Hoadley, 2011).

Concerns about the lack of knowledge about South African history among South African learners led to the criticism of CAPS from the African National Congress (ANC)-aligned South African Democratic Teachers Union (SADTU) in 2014 (Kukard, 2015). A Ministerial Task Team was appointed in 2015 to discuss the possibility of history becoming a compulsory subject until the end of Matric, and to evaluate the CAPS curriculum (History Ministerial Task Team (HMTT), 2018:9). The History Ministerial Task Team published a report which recommends "strengthening" the CAPS curriculum ahead of the possible introduction of the subject as compulsory (HMTT, 2018:48). Particular attention is paid to improving the connections to a broader African context within the existing CAPS content (HMTT, 2018). The report shows contradictory imaginings of what kind of academic and civic identities should be privileged, arguing for the importance of history as "instilling love of country" (HMTT, 2018:8) but also that it "produces a critically skilled citizen" (HMTT, 2018:40), and recognises the importance of history as "a discipline" (HMTT, 2018:41). It is therefore timeous to consider the ways in which other curriculum documents have dealt with these questions.

Reasons for selecting these four documents

The four curriculum documents2 are:

• The first English National Curriculum, published in 1991;

• The revised English National Curriculum, published in 2014;

• Curriculum 2005: Lifelong learning for the 21st century, published in 1997;

• Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement: Grades 7-9 Social Sciences, published in 2011.

Given the current discussion around decolonising the curriculum, it may seem counter-intuitive to be examining English history curricula alongside South Africa curricula. The Ministerial Task Team made a concerted effort in their research to consider history curricula from developing nations, with a particular focus on African nations. However, they also considered some European history curricula (Poland, Netherlands, Italy, France, Austria, Norway and Russia) (HMTT, 2018). The purpose of the study was descriptive and not prescriptive in nature; there was no sense that the South African curricula should resemble the English curricula. Instead, the four curriculum documents have been chosen in order to facilitate a comparative study of the shifts in imagined identity. The methodology could be applied to comparing any curricula.

Theoretical framework: Pedagogic discourse

School history is a recontextualised form of the academic history discipline and produces particular academic identities. It is, however, also a subject that governments can use to shape civic identities through both explicit and regulative discourses (Bernstein, 2000). Drawing on the work of Althusser, Durkheim and Marx, Bernstein sees the ways in which education is framed and classified as being ideologically bounded (Bernstein, 2000). For Bernstein, "the battle over curricula is also a conflict between different conceptions of social order and is therefore fundamentally moral" (Bernstein, 1975:73). Bernstein's categories allow the researcher to examine the ways in which the structure of the curriculum itself and the pedagogic discourse that emerges imagine the academic learner and citizen.

The instructional discourse creates "specialised skills and their relationship to each other", but is itself a recontextualised, imaginary subject discourse which has been de-located and relocated from the site of production (Bernstein, 1990:160) and therefore undergoes an "ideological transformation" (Bertram, 2012:5). The strength of the classification of the selection, sequence and pace of this "imaginary subject" is governed by regulative discourse, which provides the moral ordering of "relations and identity" (Bernstein, 2000:32). Recontextualisation therefore creates not only "a what but a whom" (Thompson, 2014:37) for Bernstein: the 'imaginary subject' (Bernstein, 1990). Pedagogic discourse is the rule which results in the "embedding" of the instructional discourse (curricular content and competencies) in the regulative discourse ("social conduct, character and manner") (Bernstein, 2000:32, Singh, 2002:573). For Bernstein, the regulative discourse is always dominant in this process of embedding (Bernstein, 1990).

The terms academic and civic identity are not ones that Bernstein uses directly, but they map onto these concepts of instructional and regulative discourse. Through the relationship between the two, the academic consciousness of the instructional discourse is generated by the conscience of the regulative discourse. The concept of the pedagogic device therefore allows me to unpack the structuring of identity in the history curriculum (Bernstein, 2000). History is a subject in which it is particularly difficult to pry apart the academic and civic identities; the very nature of the subject means that the two are always very closely intertwined. The thesis did consider elements of the curriculum which reflected explicit civic identities, however, for the purposes of this article, I have focused on only three elements of the academic identities and therefore, the civic identities towards which these academic identities point.

Analytic framework

The analytic framework was created through an iterative process of working with both the data (defined below) and history education literature. The section of the analytic framework relevant to this article, on three aspects of academic identity, are presented in summary in Image 1.

The process of constituting the data set was complex as each curriculum document was structured differently. It was, however, possible to standardise the data to be analysed through dividing it into three sections: purpose statements, topics and elaborated content. The topics within each curriculum generally give the overall area of study and the elaborated content outlines the topic in more specific detail. Purpose statements are a combination of the explicit aims of the history section of the curriculum, the procedural skills and historical concepts (cause and consequence, change and continuity, chronology and so forth). Together they give an indication of the intention the curriculum writers had for the curriculum.

Findings: Academic identities in the four curriculum documents

The following discussion provides the key findings of the academic and implied civic identities which emerge in the organisation and choice of content and the key skills emphasised in the curricula

Content organising principle

This element examines the extent to which the content has been organised as a continuous narrative (chronological), key episodes (episodic) or through the tracing of a theme (thematic). The organising principle was allocated based around the specificity of dates within the topics, the level of detail provided in the elaborated content, and the presence of either explicit or implied turning points or thematic organisers. In most cases there are anomalous elements within the curriculum, but the identification corresponds to the dominant features. The curriculum could also be coded as hybrid.

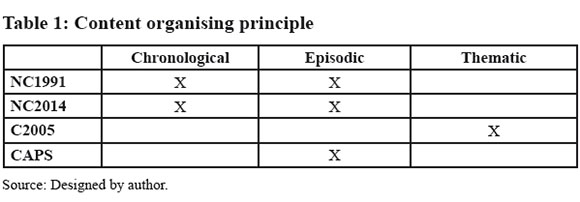

Table 1 summarises the coding of the four curriculum documents.

NC1991: Organising principle

NC1991 primarily has a chronological organising principle. Three of the eight topics have specific, contiguous dates included. For "The Roman Empire", there is a period of history implied, even though dates are not specifically included. When one examines the elaborated content of the topic, "a unit involving the study of a past non-European society" (NC1991:47), it is clear that periodisation is also an organising principle; the difference is that the teacher has autonomy over which period of world history is under consideration. Five out of the eight topics are therefore organised according to periodisation and fall within the chronological organising principle. However, there are three units which are more episodic in their organisation: Core Study Unit 5 is a key event, as it deals with the developments that led to the Second World War; Supplementary Study A and B both fall more within the episodic approach, as they are organised according to "turning points" and "depth study" (NC1991:47). The exception to this pattern is the allowance for a "thematic" study within Supplementary Study Unit A (NC1991:47). Overall, however, the chronological organising principle is most dominant, with elements of episodic.

NC2014: Organising principle

Unlike NC1991, the elaborated content outlined in NC2014 was nonstatutory. However, I included the examples of elaborated content provided in the curriculum in my analysis as I take them to be a clear indication of the kinds of detail that the curriculum writers would want teachers to cover.

NC2014 is an example of a hybrid chronological-episodic curriculum, as it provides specific chronology within the topics. Although NC2014 does have some thematic and depth study topics and one topic which does not specify any dates "a significant society or issue in world history" (NC2014:97), it shows a very strong favouring of specific periodisation as an organising principle. However, the specificity of the dates indicates that the curriculum writers had particular events in mind as crucial markers of period. For instance, "1066" marks the Battle of Hastings, which is the beginning of the medieval period according to the curriculum writers; "1509" marks the date of Henry VIII's ascent to the throne of England, marking the beginning of the Tudor period. The 2014 National Curriculum therefore has elements of a strong chronological approach, but tempers this with an expectation that the pedagogic decision of what elements of the topic to teach will take on a somewhat episodic dimension.

C2005: Organising principle

C2005 is strikingly different from the other curricula and gives no indication of limiting either dates or period in any of the topics. C2005 is strongly organised according to thematic principles. Within both the topics and the elaborated content, there are no specific dates mentioned. The only references to timescale are general, such as "Pre-colonial, colonial, post-colonial, Apartheid, post-Apartheid" (C2005:HSS6).3 This is in part due to the design features of the curriculum, which aimed to allow for a "flexibility in the choice of specific content and process", following the competence approach (Ministry of Education, 1997:17). The teacher therefore has almost complete autonomy over which periods and events to cover in order to reach the overall outcomes. Thematic elements are traced in the elaborated content as is shown in Image 3.

The theme of "issues in relation to the Constitution" is explored without any clear limitation on particular periods or events. Instead, the teacher is limited only by a "past, present and future perspective" (C2005:HSS16). Overall, therefore, the approach is strongly thematic.

CAPS: Organising principle

The CAPS curriculum is strongly within the episodic category. Although some indication of dates is given, the key organising principle is turning points within history rather than an overarching chronology. Only two of the topics ["World War I (1914-1918)" and "World War II (19391945)"] (CAPS:40-41) have specific, contiguous dates listed, but even these are organised according to colligatory terms rather than long-term chronological periods. Nine out of the twelve topics are therefore organised according to colligatory terms such as "Colonisation of the Cape 17th-18thcentury" (CAPS:35) and "The Nuclear Age and the Cold War" (CAPS:42). The elaborated content is detailed but focuses on developing the central episode rather than covering a wide range of events within a period, as is the case in NC1991 and NC2014. Image 4 below shows the topic "The Transatlantic Slave Trade".

All the detail is linked to the central topic and no other events within a similar period of history are covered. The organising principle is therefore strongly episodic.

Content: Focus and region Focus

The topics and elaborated content points were coded as political, socio-cultural or economic. It is somewhat artificial to pull these elements apart as they often overlap. However, those points that were not coded as any of the above were also recorded; particularly in the case of C2005, the sizable percentage of points that did not fall into either of the three focuses is very telling. Table 2 outlines the number of elaborated content points and topics that fall within the various elements of the focus of the curriculum. Some points may be coded as multiple focuses, and thus the percentage total for each curriculum could exceed 100%.

NC1991 was structured around a deliberate attempt to have a wide range of "perspectives" including:

• political;

• economic, technological and scientific;

• social;

• religious;

• cultural and aesthetic (NC1991:33)

The elaborated content, as seen below in Image 6, is structured around these varying perspectives and for each topic the different aspects are listed under emboldened headings. NC1991 shows an even split between political and socio-cultural elements in the content. It is interesting that economic elements are considerably lower than the other two, despite the goal of including a variety of the above perspectives. Although each topic has points across all focuses, there are generally more elaborated content points for political than for the others, as can be seen in the second bullet point in Image 6.

This pattern is repeated across several topics, which has resulted in the comparatively high number of political points.

NC2014: Content focus

NC2014 shows a bias towards a political focus, with 60% of content coded, at least in part, as political. Topics such as "the development of Church, state and society in Britain 1509-1795" could potentially have a broad range of focuses. However, the ways in which the elaborated content is framed, such as "the Interregnum (including Cromwell in Ireland)" or "The Restoration, 'Glorious Revolution' and power of Parliament" (NC2014:96), have a decided political focus. While the teacher could make clear connections to socio-cultural and economic content, the political aspect is foregrounded in the curriculum document.

C2005: Content focus

It is striking that of all the curricula C2005 has the highest percentage of content with an economic focus. There was an attempt to teach history in such a way that the economic structural features of change were foregrounded. The specific outcome, "Demonstrate a critical understanding of how South African society has changed and developed" (C2005:HSS2), is the most clearly historical of all the specific outcomes. One of the elaborated content points within the Range Statement (SO1:AC2) is "exploitation of resources (including human resources), especially in relation to minerals and farming" (C2005:HSS5). The focus of this content is on the creation of inequality in society through the events around South Africa's industrialisation, migrant labour and land reform during apartheid.

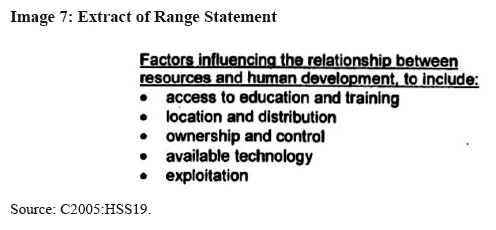

However, other elements of the elaborated content are less clearly recognisable as history. For example, the specific outcome, "Makes sound judgements about the development, utilisation and management of resources" (CAPS:HSS2), contains range statements such as in Image 7.

It is also significant that over half of the curriculum could not be identified as any of the three focuses. These points ranged from more skills-based elaborated content points, such as the "reading and construction of maps, graphs and other techniques for recognising and describing patterns" (C2005:HSS13), to content which is more clearly geography based, such as "Environmental issues to include: deforestation; over-utilisation; soil erosion; etc." (C2005:HSS21). There are also several points which are non-academic, such as "Significance of attitudes and values in ... personal decision making" (C2005:HSS31).

CAPS: Content focus

In sharp contrast to C2005, CAPS show a decided bias towards political content. Although the curriculum follows a broadly episodic organising principle (as discussed above) the overarching approach is of turning points in the formation of the South African nation. As with NC1991 and NC2014, much of the content can be identified as part of the narrative of politics. For topics such as "The Nuclear Age and the Cold War" (CAPS:41) or "Turning points in South African History 1960, 1976 and 1990" (CAPS:44), all the elaborated content points could be coded as political.

However, it is interesting that there is an even balance between the socio-cultural and economic content. There is still a sense that history is the study of "change and development in society over time" (CAPS:9) and therefore that all aspects of human society need to be examined.

Region

The topics and elaborated content points were also coded according to region: local, national, continental, global or not coded. The following table outlines the number of elaborated content points and topics that fall within the various elements of the region of the curriculum. Some individual points may be coded as multiple focuses, and thus the percentage total could exceed 100%.

NC1991: Content region

There is a clear focus in NC1991 on national history. This corresponds to the above discussion around the political Focus of the curriculum. The curriculum does teach a sizeable element of European history and one topic out of the eight is focused entirely on world history. In several other topics, British history is taught within the context of connections with Europe and the rest of the world. For example, in the topic "The era of the Second World War", the elaborated content deals with national content such as "the home front in Britain", continental content such as, "the redrawing of national frontiers in Europe", and global content such as "the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki" (NC1991:45). Two out of the eight topics are specifically continental in their Regional Focus: "The Roman Empire" (NC1991:37) and "A unit involving the study of an episode or turning point in European history before 1914" (NC1991:47).

NC2014: Content region

NC2014 favours national history very strongly. Five out of the seven topics are primarily national in focus. While elements of the elaborated content, such as "the French Revolutionary wars" in the topic "ideas, political power, industry and empire: Britain 1745-1901" (NC2014:96) could be coded as continental, the framing of the overall topic emphasises that it is British history that is the priority.

C2005: Content region

C2005 has by far the lowest incidence of national history of the four curriculum documents (43%). It also has by far the highest percentage of local history of the four curriculum documents (33%). A local regional focus does not necessarily entail non-historical knowledge, and some elements such as "issues of nation-building" were to be considered "from the local/community" within periods from "pre-colonial times to the present" (C2005:HSS11). However, other points were non-historical, such as "issues: local (e.g. lack of security at school)" (C2005:HSS33). While a sizeable percentage of the content could be coded as national, it is very striking that such a high percentage has a local regional focus.

CAPS: Content region

CAPS is the only curriculum that has a higher percentage of global (50.4%) than national (43.5%) history. Of the sixteen elaborated content

points within the topic "World War I (1914-1918)", only three could be

coded as national; the rest are all global. In the topic, "World War II (19391945)", all twenty-four elaborated content points were coded as global.

CAPS also has almost no local history, with the one exception being that the project suggested for Grade 9 Term 3 on South African history allows for teachers to choose their own topic according to the "learner's context" (CAPS:14). Overall, the national and global regional focuses dominate.

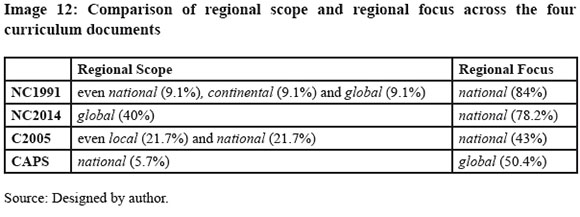

Regional scope

In addition to considering the way in which the content was divided according to region, the purpose statements were also coded according to local, national, continental or global. This allows for a discussion of the extent to which the content choices reflect the intentions of the curriculum writers.

NC1991: Regional scope

It is interesting that NC1991 makes equal reference within the purpose statements to national, continental and global regional scope. This is in sharp contrast to the reality of the content, which, as discussed above, has a strongly national regional scope (84%). Although both continental and global are present in the curriculum, they are by no means of equal weight. The hope that the curriculum would "enable pupils to develop knowledge and understanding of British, European and world history" (NC1991:11) is therefore not matched by the content selected.

NC2014: Regional scope

It is striking that NC2014 makes more reference to global concerns than national in the purpose statements. The content did have 25.5.% global coding, so this regional scope is visible in the content. It does not, however, correspond to the high level of national content that is prescribed. This could be due to a sense that Britain's role in the world was changing and that part of the role of the history curriculum was to prepare learners for the "challenges of their time" (NC2014:94). The increased visibility of connecting as a key competency, as discussed below, supports this viewpoint.

Thus, both English curricula therefore present themselves as having a broader regional scope than is reflected within the content choice.

C2005 makes the most direct references to its regional scope out of the four curriculum documents. The specific aims element of the curriculum does see understanding national history as an important element; one of the specific outcomes is: "Demonstrate a critical understanding of how South African society has changed and developed" (C2005:HSS2). The relatively high presence of local regional scope within the purpose statements compared to the other four curricula reflects its concern to valorise local knowledge (Ensor, 2003). Although there is a sense that global relations are important, such as "The interrelationships between South Africa and the rest of the world are explored" (C2005:HSS7), the local context is emphasised.

CAPS: Regional identity

The CAPS document has a relatively low incidence ofpurpose statements coded as elements of regional scope. The relatively higher level of national versus global coded purpose statements does not correspond with the content choice coding, which, as discussed above, favours global.

There was a dramatic decrease of 17.9% in local regional scope from 21.7% in C2005 to 3.8% in CAPS. National regional scope also decreased, from 21.7% in C2005 to 5.7% in CAPS. The continental regional scope

remained low in both curricula (4% in C2005 and 1.9% in CAPS). There was also a decrease, from 6.5% in C2005 to 1.9% in CAPS, of global regional focus. As was the case with the English national curricula, the regional scope and the regional focus do not correspond in the CAPS document.

Key competency

Key Competency was coded according to the primary skills that the curriculum document outlines in the purpose statements. The statements were coded individually to produce a percentage measure, but these results were then described as to whether the three skills of memorising, analysing and connecting are highly visible, moderately visible, weakly visible or mostly invisible. Memorising competencies use the language of recalling or describing and emphasise the informational aspect of knowledge; analysing competencies use the language of historical thinking and key disciplinary concepts; connecting competencies use the language of using historical thinking in order to engage as citizens and applying historical knowledge to current situations.

NC1991: Key competency

Analysing is highly visible as the key competency in NC1991. This is not surprising given the influence of the SCHP way of thinking and its influence on the creation of the curriculum. The purpose statements that were coded as memorising are generally the lower-order elements of the Attainment Targets,4 such as "describes changes over a period" (NC1991:3). Those that were coded as connecting are related to creating empathy and understanding other points of view, such as "show an awareness that different people's ideas and attitudes are often related to their circumstances" (NC1991:4). However, most of the attainment targets use the language of analysing, such as "make deductions from historical sources" (NC1991:9).

NC2014: Key competency

It is interesting that NC2014 has such a wide spread of key competencies compared to NC1991. Connecting the past to the present is seen as being equally as important as analysing. Statements such as the following were coded as connecting:

History helps pupils to understand the complexity of people's lives, the process of change, the diversity of societies and relationships between different groups, as well as their own identity and the challenges of their time (NC2014:94)

There is a clear sense that history education should result in citizens who are engaged with the current realities of society. This aspect was absent from NC1991.

The pressures of memorising are still clearly seen in purpose statements like:

... know and understand the history of these islands as a coherent, chronological narrative, from the earliest times to the present day: how people's lives have shaped this nation and how Britain has influenced and been influenced by the wider world (NC2014:94).

The emphasis here is not on rote memorising, as students must still "understand" the history, but they will not be able to say that they have fulfilled the requirements of the curriculum if they do not also "know" it "coherently". However, the importance of analysing remains, and the attainment targets of NC1991 are recognisable in statements such as:

... understand the methods of historical enquiry, including how evidence is used rigorously to make historical claims, and discern how and why contrasting arguments and interpretations ofthe past have been constructed (NC2014:94).

Overall, there has been a shift from a very strong focus on analysing as the key competency to a broader vision of the key competencies that history education should produce.

C2005: Key competency

C2005 has a very strong focus on connecting as the key competency. There is a particular focus throughout the curriculum on the competencies of debating and discussion. This is shown in purpose statements such as "The means of making voices heard, and for obtaining information, should be discussed and strategies agreed on" (C2005:HSS18). This is also reflected in the emphasis on group work within the curriculum.

The lack of focus on memorising is not surprising given that C2005 was written in reaction to the perceived rote-learning approach of the previous apartheid curricula. The only points which are relevant to memorising are those where the retelling of stories is required, such as "give an account of the changes experienced by communities, including struggles over resources and political rights" (C2005:HSS6). The focus of memorising in this example is therefore community based, rather than memorising the coherent narrative of the nation state as a whole.

The low incidence of analysing in comparison to the other curricula is due to the lack of specification of C2005 as a history curriculum. A number of the points that were coded as analysing were in fact more relevant to geography, such as "analyse the causal factors and the relationships which influence the extent of the impact of natural events and phenomena on the lives of people" (C2005:HSS29). There was evidence of more history-specific analysing competencies, such as "deducing and synthesising information from sources and evidence" (C2005:HSS37) but this was not highly visible.

It is also interesting that this section is the area with the lowest level of not coded points. This is likely because C2005 is an outcomes-based curriculum and therefore frames most of its material as skills and purposes rather than specific content.

CAPS: Key competency

CAPS has a fairly strong focus on analysing as the key competency, but connecting still plays a significant role. The curriculum is clearly more strongly specified as historical and it therefore prioritises analysing purpose statements, such as "History is the study of change and development in society over time" (CAPS:9). However, like NC2014, connecting also has an important role to play, as history is also about "learning to think about the past, and by implication the present in a disciplined way" (CAPS:9 emphasis mine). CAPS is therefore in strong contrast to C2005, which focused on connecting as the primary competency.

Shifts within academic identities in the four curriculum documents

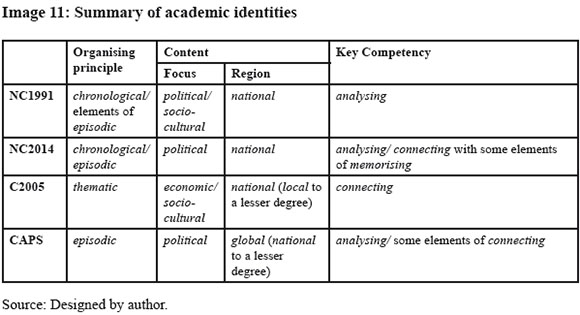

Image 11 characterises the various elements of the academic identities found within the four curriculum documents.

Within the English national curricula, the organising principles have remained much the same. There is a stronger sense of a chronological organising principle within NC1991 than in N2014, but it does still have visible elements of an episodic organising principle. The tension between chronological and episodic, which is present in both curricula, could be a result of the wider tension between the progressive influence of the approaches of SCHP versus the traditional concerns of Thatcher in 1991, and Gove in 2014. Depth and overview and thematic "lines of development" approaches were a key part of the approach adopted within the SCHP curricula (SCHP, 1976:43-46). As discussed in the introduction, both Thatcher and Gove had a very clear conception of what constituted a valid history curriculum; that is, a chronological narrative. The tensions between the more episodic and chronological approaches could be a by-product of these contrasting pressures placed upon the history curriculum writers.

By contrast, the South African curricula showed a dramatic shift in terms of organising principle. Whereas C2005 follows a thematic organising principle, CAPS follow a strongly episodic organising principle. The thematic organising principle in C2005 allowed for the teachers to have great freedom in what content they chose. The avoidance of a chronological approach could be explained because C2005 was a reaction against the apartheid-era use of superficial content-heavy approaches, which relied on rote drilling pedagogies (Nykiel-Herbert, 2004:251). The change in CAPS to an episodic approach is reflective, at least in part, of the influence of the "turning points" approach from the SCHP on South African history educationalists.

It is interesting, however, that neither South African curricula make use of a chronological organising principle, compared to the English curricula where its use is quite prominent. The kind of academic identity that the English curricula hope to produce therefore has a strong emphasis on understanding chronology. C2005 is more concerned with tracing key themes, while CAPS see understanding key turning points as the most important element.

Content: Focus and region

In relation to content, the English curricula both showed a clear focus on political and national content. There was a slight increase in political content from NC1991 (51%) to NC2014 (60%) and a slight decrease in national content from NC1991 (84%) to NC2014 (78.2%). Socio-cultural was the second most visible element of the content focus. This aspect also decreased slightly from NC1991 (47.5%) to NC2014 (40%). In both curricula, the economic focus had the lowest incidence (16.3% in NC1991 and 12.7% in NC2014). Local history increased from NC1991 (1.3%) to NC2014 (7.3%). In NC1991, continental history made up 35%, which was by far the most across all four curricula. In NC2014, this had decreased to 14.5%. Inversely, global content increased from NC1991 (17.5%) to NC2014 (25.5%). The incidence of non-coded items in both English curricula remained relatively low. Overall, the regional focus of the content in both curricula was dominated by national content. While there was a significant emphasis on socio-cultural material, the political content was more evident.

As with the pressure for a chronological organising principle, there was a pressure on both NC1991 and NC2014 reforms for a national political focus in the telling of the narrative of the formation of the nation state (Baker, 1993:167-168). Thatcher was "appalled" in particular at the lack of focus on British history in the History Working Group's proposed history curriculum, which is perhaps part of the reason that the final curriculum has a higher level of national political history (Cannadine, Keating & Sheldon, 2011:194) Similarly, Gove's revision of the national curriculum was prompted in part by the concern that there was a lack of knowledge about national history (Fordham, 2012). The ongoing tensions about the purpose of history education within England can thus be seen in the dynamics within the content selection.

Both South African curricula show a substantially lower percentage of national history compared to the two English curricula (C2005 - 43% and CAPS - 43.5%). It is interesting that there had not been much shift between the two South African curricula in relation to the percentage of content related to national history. However, whereas C2005 had 33% of its content coded as local, only 0.4% of the CAPS content could be coded as local. It is likely that the focus on local content within C2005 was aimed at preventing authoritarian, top-down approaches, in direct contrast to the approach of Christian National Education during apartheid (Nykiel-Herbert, 2004:258). On the other hand, C2005 had only 23.6% global content, whereas CAPS had 50.4%, by far the highest of all four curricula. There has therefore been a major shift from a significant focus on local history in C2005 to a much more global focus in CAPS. Both curricula had a relatively low incidence of continental content (C2005 - 16.6% and CAPS - 15.7%). South Africa is therefore not clearly positioned as an African nation in either curriculum. Compared to the English curricula, both South African curricula have a much lower incidence of national content.

There was a relatively low incidence of political content within C2005 (11%) compared to CAPS (54.3%). Given the fractured nature of South African society after the end of apartheid, it is interesting that the curriculum reform did not create a strong narrative of the building of the nation state. There was a moderate increase in socio-cultural content, from 18.5% in C2005 to 28.2% in CAPS. The level of economic content remained consistent at 22.4% in C2005 to 24.3% in CAPS. However, given the high incidence of non-coded items in C2005, economic was the highest of all the content focuses. There has therefore been a shift in academic identity in relation to content, from a prizing of economic and socio-cultural interpretations of local history in the context of national history, to a greater focus on political history of the nation within a global context.

It is interesting that none of the curriculum documents' dominant regional scope corresponds to the regional focus as seen in Image 12:

This suggests that there are some tensions in the way in which the curriculum documents would want to imagine the regional identity of the history learner. The expressed aims of the Regional Scope within the purpose statements and the regional focus within the substantive content prescribed are in some cases (such as NC1991) completely undermined by the actual content prescribed.

In relation to key competency, NC1991 has by far the highest visibility of analysing (81.3%). By comparison, NC2014 has only moderate visibility of analysing (40%). There was an increase in memorising from 12.5% in NC1991 to 30% in NC2014, which therefore constitutes a shift from weak to moderate visibility. There was also an increase in the visibility of connecting from 25% in NC1991 to 40% in NC2014. Although connecting remained moderately visible in both curricula, the increase of 15% of purpose statements related to connecting is significant. The main shifts with the imagined academic identity are therefore from a strong focus on analysing in NC1991 to a more balanced view of all three key competencies within NC2014.

The strong focus on analysing within NC1991 is perhaps reflective of the tension between the History Working Group and the more traditional pressures refusing to have content knowledge as the goal of the attainment targets, and instead insisting upon defining "principles of assessment" based around "conceptual development" (Guyver, 2012:166). These "principles" embody many of the key competencies of analysing, as they reflect skills in constructing and engaging with historical accounts. The fact that NC2014 has a more varied view of key competency is perhaps reflective of the increasing influences of concerns about citizenship and making the curriculum relevant to the problems facing modern society,5and the ongoing pressure of more traditional views of history education, which favour memorising a national chronological story.

Memorising remained mostly invisible within both C2005 (7.6%) and CAPS (5.7%). The low level of memorising is probably in part a reaction against the apartheid-style rote learning of content. It is interesting that the CAPS document does still include an indication that "memory skills remain important", but that this is given within the context of not driving a wedge between understanding content and developing historical skills and aims (CAPS:11). By contrast, analysing increased from moderately visible in C2005 (34.4%) to highly visible in CAPS (56.6%). This is in part since CAPS is much more clearly specified as a history curriculum and foregrounds historical thinking. The increased role of analysing is perhaps also indicative of the influence of the English curriculum reforms on the CAPS curriculum writers. There was also a shift from connecting being the primary key competency within C2005 (53.6%) to being only moderately visible within CAPS (43.4%). The key competency has therefore shifted across the South African curriculum reforms from connecting in C2005 to analysing in CAPS.

NC1991 is thus the curriculum where analysing is seen as by far the most important. The other three curricula see it as important, but not to the same degree. Connecting has remained an important key competency in the South African curricula, whereas the role of this key competency has increased in significance across the English curriculum reforms.

Academic identities in relation to civic identities

The elements of the results related to academic identity also provide elucidation on the ways in which the instructional discourse is embedded within the regulative discourse. For NC1991, there are tensions between attempts to produce a history student who has a strong chronological understanding of the political narrative of the nation, and a student who also understands what life was like for ordinary citizens. The focus on a key competency of analysing within this curriculum shows a privileging of critical thinking over memorising.

In relation to content, the instructional discourse within NC2014 has not changed much from NC1991. There is still a focus on a chronological or episodic approach to a national political history. The major shift within the key competencies has been towards connecting. This shows an increased focus on the ways in which history can shape students' experience of the current world.

Unlike the English national curricula, where there are limited shifts within the instructional and regulative discourses, the differences between the two South African curricula represent a major shift. Whereas C2005 takes a thematic approach to primarily socio-cultural and economic content, CAPS focuses on an episodic approach to political content. While both curricula have a strong national element, it was far less so than in the English curricula. CAPS also focuses more on global than national. There was also a shift from primarily connecting key competency in C2005 to an increase in the visibility of analysing in CAPS. The regulative discourses shaping these instructional discourses are therefore showing a shift from a citizen connected to their local issues in the context of the nation, in C2005, to a critical thinking citizen aware of global trends, in CAPS

Relating the CAPS findings to the Ministerial Task Team Report

The Ministerial Task Team Report's recommendations are based on its analysis of the CAPS document. It is well beyond the scope of this paper to do an in-depth analysis of the Report. However, some key themes regarding the kinds of academic and civic identities that the Report sees in CAPS can be compared to the findings discussed above. The Report discusses CAPS from Grades 4-12, whereas my analysis was just on Grades 7-9. It would be interesting to extend the study to cover Grades 4-6 and 10-12. Despite this, it is instructive to consider the ways in which the characterisation of CAPS within the Report is accurate based on the above findings.

The Report argues that the "chronological sequencing is poor" and that "history is taught in 'bubbles'" (HMTT, 2018:80). This corresponds to the finding that CAPS is episodic in its organising principle. The Report also observes that the broad chronological breakdown of topics does, however, also mean that topics of earlier African history are covered in primary school before learners are able to engage with them at a sophisticated level (HMTT, 2018:41).

One of the key recommendations of the Ministerial Task Team report was that the CAPS curriculum needed to be strengthened regarding an African focus as "the content is still sanitised in terms of teaching African History" (HMTT, 2018:7). This corresponds to the findings that there was more global content than national and a very low incidence of continental. The Report does therefore seem to be justified in seeking to strengthen the African and South African content within CAPS and to work towards producing learners who work with "conflicting history on a continental, national or personal level" (HMTT, 2018:41). The Report's discussion does not deal directly with the issue of the balance of political, socio-cultural and economic content. However, it does argue that learners need to know "many layers" (HMTT, 2018:40). Two examples where the report seeks to extend the content focus of CAPS is in adding more gender balance and in including a "religious perspective" on some topics (HMTT, 2018:40; 79). Overall, the Report's characterisation of CAPS does seem to concur with the findings above.

In terms of key competencies, the Report argues that CAPS has "just content for content's sake" (HMTT, 2018:40), suggesting that it encourages a memorisation approach. This is a major point of disagreement between the findings and the Report. CAPS in fact emphasises both analysing and connecting the content learned to the current day issues in South Africa. According to the Report the goal of history should be:

...to produce a critically skilled citizen who is capable of handling multiple kinds of perspectives and who is able to recognise his or her individual intellectual role in adjudicating knowledge (HMTT, 2018:40-41).

As CAPS does promote the disciplinary thinking involved in "adjudicating knowledge", this should be considered when reworking the curriculum. According to the Report, the "main objective" of history is to "produce a learner who knows the 'story' of who we are in its many layers" (HMTT, 2018:40). This call for a "story" echoes the discourse of the importance of telling "our island story" used by Gove and others in the 2014 English curriculum reforms (Gove in Fordham, 2012:242). The Report is not clear about how to avoid the difficulties, faced in the English curriculum reforms, between teaching analytical, disciplinary thinking and knowing a coherent "story", which the Report does claim it wants to avoid (HMTT, 2018:42).

Conclusion

Through analysing the shifts in the academic identities which emerge in these four curriculum documents, it is possible to trace changing conceptions of the imagined history learner. The analytic framework allowed for a fine-grained analysis and provides a method for evaluating claims about a curriculum, such as those made by the Ministerial Task Team Report about CAPS.

The current debates about the kind of history learner the South African history curriculum should seek to produce need to be considered in view of preceding curriculum reforms both in South Africa and internationally. This presents an opportunity to build on the strengths and to avoid the weaknesses of past curricula.

References

Baker, K 1993. The turbulent years: My life in politics. Faber & Faber: London. [ Links ]

Bernstein, B 2000. The pedagogic device, pedagogy, symbolic control and identity. Taylor and Francis: London. [ Links ]

Bernstein, B 1990. The social construction of pedagogic discourse. In: B Bernstein (edt.), Class, codes and control: Volume IV: The structuring of pedagogic discourse. Routledge: London and New York. [ Links ]

Bernstein, B 1975. "On the curriculum", Class, codes and control, Volume 3. Routledge and Kegan Paul: London. [ Links ]

Bertram, C 2012. Bernstein's theory of the pedagogic device as frame to study history curriculum reform in South Africa. Yesterday and Today, 7:1. [ Links ]

Bertram, C 2008. Doing History. Journal of Education, 41:155-177. [ Links ]

Cannadine, D, Keating, J & Sheldon, N 2011. The right kind of History: Teaching the past in twentieth-century England. Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke. [ Links ]

Counsell, C 2014. On being guardians of an 's': who will polish and protect the curriculum jewel of interpretation(s) plural?. Schools History Project 26th Annual Conference, 12 July 2014. [ Links ]

Department for Education 2014. The National Curriculum in England: Key Stages 3 and 4 Framework Document. The Stationery Office: London. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education 2011. History Curriculum and Policy Statement: Further Education and Training Phase. Department of Basic Education: Pretoria. [ Links ]

Department of Education 1997. Curriculum 2005: Lifelong learning for the 21st century. Department of Education: Pretoria. [ Links ]

Department of Education and Science 1991. History in the National Curriculum. HMSO Publications: London. [ Links ]

Ensor, P 2003. The NQF and higher education in South Africa: Some epistemological issues. Journal of Education and Work, 16(3):325-346. [ Links ]

Fordham, M 2012. Disciplinary History and the situation of History teachers. Education Sciences, 2(4):242. [ Links ]

Guyver, R 2012. The History Working Group and beyond: A case study in the UK's History quarrels. In: T Taylor & R Guyver (eds.), History wars and the classroom: Global perspectives. Information Age Publishing: Charlotte. [ Links ]

History Ministerial Task Team (HMTT) 2018. Report of the History Ministerial Task Team for the Department of Basic Education. Department of Basic Education: Pretoria. [ Links ]

Hoadley, U 2011. Knowledge, knowers and knowing: Curriculum reform in South Africa. In: L Yates and M Grumet (eds.). Curriculum in today's world: Configuring knowledge, identities, work and politics. Routledge: London. [ Links ]

Kukard, K 2015. Content choice: A survey of history curriculum content in England since 1944. A relevant backdrop for South Africa. Yesterday and Today, 13:17. [ Links ]

Ministry of Education 1997. Government Gazette, 18051st edn. Ministry of Education: Pretoria. [ Links ]

Nykiel-Herbert, B 2004. Mis-constructing knowledge: The case of learner-centred pedagogy in South Africa. Prospects, 34(3):249-265. [ Links ]

Schools Council History 13-16, Project 1976. What is history? Teachers' guide. Edinburgh: Holmes-McDougall: Edinburgh. [ Links ]

Singh, P 2002. Pedagogising knowledge: Bernstein's theory of the pedagogic device. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 23(4):571-582. [ Links ]

Thatcher, M 2013. Margaret Thatcher: The Autobiography. Harper Press: London. [ Links ]

Thompson, A 2014. SEXUAL TENSION: The imagined learner projected through the recontextualising of sexual knowledge into pedagogic communication in two curricula in South Africa and Ontario, Canada. Master's edn, University of Cape Town:Cape Town. [ Links ]

Vasagar, J 2011. 24 November 2011-last update, Michael Gove accuses exam system of neglecting British history [Homepage of The Guardian]. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/education/2011/nov/24/michael-gove-british-history-neglected. Accessed on 6 March 2017. [ Links ]

Witz, L and Hamilton, C 1991. Reaping the whirlwind: The Reader's Digest illustrated History of South Africa and changing popular perceptions of History. South African Historical Journal, 24(1):185-202. [ Links ]

1 The article draws heavily on my master's thesis, submitted in May 2017 at the University of Cape Town. For the sake of brevity, I have not referenced every point.

2 For the sake of brevity, the curriculum documents are referred to as NC1991, NC2014, C2005 and CAPS respectively in the in-text referencing. The full bibliographic details are available below.

3 HSS refers to Human and Social Sciences and is the relevant section of the Curriculum 2005 document.

4 Attainment Targets were the statements of outcomes for NC1991. They were controversially framed in terms of historical skills and concepts rather than key content.

5 Particularly after the Crick Report (1998) and Ajegbo Report (2007) on issues of citizenship.