Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Yesterday and Today

On-line version ISSN 2309-9003

Print version ISSN 2223-0386

Y&T n.21 Vanderbijlpark Jul. 2019

HANDS-ON ARITCLE

Navigating the tension between official and unofficial History – a teacher's view

Zoleka Mkhabela

Hillview Secondary School Newlands East, Durban. zoleka.mkhabela@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Growing up in the post-apartheid era in a township on the outskirts of Durban, and schooling in Durban North, I always wondered why the houses in KwaMashu township were small, clustered and all looked similar compared to the houses where I schooled. Although I grew up questioning this, I would never discuss such topics with my parents. So, when the topic of apartheid was taught in school "it all made sense" until I did an oral history project on my grandmother, Sibukeli Angelina Mbokazi, who was a domestic worker during the apartheid regime. My grandmother felt differently from what I thought she would, which severely challenged me. This was especially the case because my grandmother and my mother were victims of the apartheid era land dispossession laws. This article articulates the internal challenges I have faced in the history classroom when the unofficial history of my family, as articulated by my grandmother, conflicted with the official curricula and textbooks.

Keywords: Competing discourses; Apartheid; Group Areas Act; Land Act; History; Teaching; Learning.

Introduction and background

At the outset let me confess - I am confused, torn and conflicted among the complexity of my family's history (what would be called unofficial history) as it relates to land dispossession during apartheid and the official history related to such events learnt as part of National Curriculum Statement (NCS) and the Curriculum Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) or what would be called official history (sanctioned by the state via the curriculum and the programmatic curriculum or textbooks). Let me explain: I am aware and versed in the historical thinking skill of multi-perspectivity. This I came to understand very well when doing my MEd in History Education, on Teachers' views on making history compulsory (Mkhabela, 2018), at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, under the supervision of Prof Johan Wassermann and Ms Leevina Iyer. I also know that globally, in diverse classrooms, where multiple backgrounds and beliefs meet, history teachers are confronted with overlapping perspectives. In such classroom's beliefs, values, attitudes, words, acts, and social identities are placed, shared and contested. Since each individual history teacher holds his/her own perspectives, thoughts and belief systems, it is inescapable that teachers will enter the classroom and never teach a perspective within the curriculum that could or could not contradict their own. In this regard, Ball (1994) and Taylor (1997), argue that the intended curriculum can create further contradictions since competing perspectives, agendas and ideologies operate to shape what is taught. In short, the history classroom contexts in which a multitude of perspectives overlap can cause conflict, leaving teachers like me feeling powerless to structure learning around controversial issues (Delpit, 2001).

Considering the above, as a history learner and later a teacher, I have at times felt severely challenged when teaching the official history on apartheid, especially as it relates to land dispossession, when it contradicted the unofficial history of my family as relayed by my grandmother, Sibukeli Angelina Mbokazi. This is where the conflict in me lies - on the one hand official history has been accepted as authentic and reliable but unofficial history has not been recognized as such. Now what is the fear around unofficial history? Kaye (1996), explains that unofficial history is normally feared because of its otherness in terms of ideological and cultural significance. Occasionally, I have found myself having to silence my voice (actually my grandmother's) and only draw on the CAPS-History curriculum and the textbooks while ignoring my grandmother's politically problematic account. In the process I felt torn between the competing official and unofficial history narratives, between my grandmother's oral accounts and the scholarship I have studied and to which I subscribe. Consequently, this reflective teacher's voice articulates the personal challenges that I have faced in the history classroom when confronted with the official history of apartheid, especially as it relates to land dispossession. However, before I tell the story of my conflict, I firstly must place my family and its apartheid era history in the bigger historical picture.

A brief history of land ownership and dispossession in South Africa

Ownership of the land has been in the political foreground in South Africa of late. In the process current land ownership patterns are presented as a major cause of inequality, insecurity, landlessness, homelessness and poverty (Dlamini, 2016). Land ownership in South Africa has deep historical roots, predating the European settlement at the Cape of Good Hope in 1652, and stretching into the present. Key historical time markers in this regard include, but are not restricted to, the arrival of Jan van Riebeeck under the auspices of the Dutch East India Company, the upheavals of the Mfecane and the Great Trek, the creation of the Union of South Africa, and the National Party taking power in 1948 and the implementing of apartheid. Specific legislation related to land ownership includes: The Native Land Act, Act 27 of 1913 (RSA, 1913), the Native Trust and Land Act, Act 18 of 1936 (RSA, 1936), and the Group Areas Act, Act 41 of 1950 (RSA, 1950) which designated just 13,7 percent of the South Africa to be set aside for Africans (Waldo, 1991). The outlined laws, alongside others, served to dispossess most of the Africans' land and excluded them from access to it (Hanekom, 1998).

Especially pertinent to the conflict I am experiencing between official and unofficial relates to Group Areas Act, Act 41 of 1950 (RSA, 1950). Urban areas, according to this Act, were to be divided into different racially segregated zones. This meant that members of one race had to live and work in an area particularly allocated to them by the apartheid government (Thompson, 1990). These areas were therefore created for the "exclusive ownership and occupation of a designated group" (Christopher, 1994:105). The Act set a clear tone for separate development. After the enactment of this Act, it then became a criminal offence, for which one could be prosecuted, if found to be living or owning land, without permission, in an area designated for another race other than one's own (Dyzenhaus, 1991).

After the unbanning of the African National Congress (ANC) and the release of Nelson Mandela, the National Party (NP) under President FW De Klerk, had the task to put measures in place to remove the racially based laws which characterised the apartheid regime. Many of these laws facilitated land allocation, occupation and user rights. The laws which had to be repealed were outlined earlier (Kloppers & Pienaar, 2014). In March 1991, a White Paper on Land Reform was published, which facilitated the repeal of both the 1913 and 1936 Land Acts together with the Group Areas Act. From here onwards, the National Party enacted the Abolition of Racially Based Land Measures Act of 1991. This Act was promulgated to:

Repeal or amend certain laws so as to abolish certain restrictions based on race or membership of a specific population group on the acquisition of land and utilization of rights to land; to provide for the rationalization of phasing out of certain racially based institutions and statutory and regulatory systems repealed the majority of discriminatory land laws.

Subsequent to the above, and the ANC coming to power in 1994, land reform as a policy, in South Africa, had three pillars: land restitution; land redistribution and tenure reform (Dlamini, 2016). Broadly speaking, this policy, intended to "redress the injustices of apartheid; to foster reconciliation and stability; to underpin economic growth; and to improve household welfare and alleviate poverty" (Department of Land Affairs, 1991:i). The continuing distribution of land ownership along racial lines is a well-known phenomenon in South Africa. As a result, land reform in South Africa has been the centre of much debate over the past two decades and many policies have been enacted. However, recently the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), have expressed unapologetically the idea of the expropriation of land without compensation from White owners which they consider will redress the inequalities of the past. To those who share this sentiment the reform of land ownership is one of the ways to redress the land ownership inequalities brought about by the colonial and apartheid eras. In his study Cousins (2016:11) argued that in resolving the land question, policies must aim at redressing "... the long-term legacies of large scale land dispossession that took place both prior to and after the 1913 Natives Land Act, that includes a divided and often dysfunctional space- economy, deep-seated rural poverty and lop-sided power relations in the countryside".

My grandmother and her family's story related to land dispossession

Now how does my grandmother's story relate to the big picture as outlined above? My maternal grandmother's family originally moved from Pongola in the northern parts of Natal (since 1994 known as KwaZulu-Natal), to Durban. More specifically they moved to eMkhumbane (Cato Manor) hoping for better living conditions and employment. eMkhumbane, just to the north of the Berea Ridge, was in close proximity to Durban which made for easy access to the city.

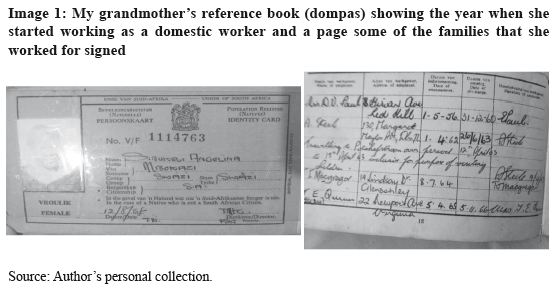

My grandmother secured a job, as a domestic worker, one of the few that was available to Africans at the time. My grandmother was 28 years old and she settled into the life of a domestic worker, a job she did until she was 60 years old. Being a domestic worker during the apartheid era my grandmother worked for six different families, from the period of 1956-1992, in the Durban areas of Redhill, Durban North; Glen Ashley and La Lucia. In the process she had to carry her "dompas" (see Image 1) to do so. Working for these families, my grandmother "lived in" and would go home only during weekends to visit her two daughters one of which is my mother. Alternatively, they would visit her. My mother left her two daughters in the care of their grandmother (my grandmother) in eMkhumbane.

My grandmother and her family lived in eMkhumbane for more than 15 years, when the Group Areas Act of 1950 was enforced (see Image 2). Subsequently, my grandmother and her family were removed and placed in a newly constituted township far outside of Durban, named after Marshall Campbell, called KwaMashu. When people were removed to KwaMashu, there were two household types they could be allocated: a two-room or a four-room house. This all depended on family type. If a person was single, he/she was assigned a two-room house and if a person was married, he/ she was placed in a four-room house. My grandmother was not married, although, she had two daughters. However, within the law, she qualified for a two-room house, a tiny house that had one room for the bedroom and the second room could be for the kitchen, lounge, dining room or a toilet-an inhumane housing environment that would not be suitable for three or more people.

In the context of the above my grandmother explained that "working in", was better than going home every day as this would allow her to assist her daughter's needs more readily as she saved on transport and other costs. Image 2 shows the letter that states that my grandmother and her daughter (Daphne Mbokazi, my mother) were removed from Cato Manor and placed in KwaMashu. Being placed in KwaMashu and allocated firstly a two-room and later a four-room house (more about how that happened will be explained lower down), ameliorated life for my grandmother's family.

When apartheid ended and the land reform process started, my grandmother submitted the supported documents (see Image 2) to lodge a land claim. My grandmother lodged a claim in 1995 (four years after I was born) at the land claims court, with the hope of getting "their land back". However, nothing transpired that met her needs. The state thought it would meet her needs, because my grandmother was offered R6000 or a piece of land on the outskirts of Dundee, by the Department of Land Affairs. My grandmother refused both offers, because to her, she was removed to Durban, and wanted a piece of land in Durban and not in Northern Natal. So, my grandmother waited, waited until the year she passed away in 2011 with her land claim being unresolved. When my grandmother passed away, my mother took over, and to this day, my mother has been waiting for land restoration, as stated in the three pillars of land reform.

Although land reform policies have been put in place to redress the inequalities of the past, this policy has failed my grandmother as her land claim has not been resolved. When the policy was put in place the government underestimated the process of land reform (Hall, 2004a). The policy was good on paper but hard to implement which makes me wonder, how many land claims have been resolved. I believe the ongoing call for land expropriation would not be happening if claims had been resolved and people who were dispossessed had received "some piece of land back".

My oral history project

Growing up in the township of KwaMashu to where my mother and grandmother were removed and being schooled at Northlands Girls High in a former White suburb, made me wonder why my neighbourhood was not like the one in which I was schooled. I always questioned why the houses in KwaMashu were small, clustered, looked the same and had facilities such as the bathroom and toilets outside which were so different from the houses where I schooled. However, whenever I would raise such questions my parents were always reluctant to give me answers. This is because topics such as apartheid, the laws and legislation of apartheid were never discussed in my household. It was not explained that the present-day effects of apartheid laws and legislation are still visible in the racial territorial divisions within South Africa. Therefore, the historical legacy of land dispossessions and relocations that resulted in most Africans becoming landless and poor were not spoken about (Harley & Fotheringham, 1999; Department of Land Affairs, 1996).

At school, despite me having a wonderful history teacher, learning about the laws and legislation of apartheid made me feel resentful. I hated every bit of the section on apartheid, because I would always imagine myself in that situation, relating to growing up under apartheid and trying to make a living. I hated it when my teacher showed us videos, reading us sources and giving us work related to apartheid. So, when we had to do an oral history project on apartheid, I dreaded the whole assignment. Then, I did not know that my grandmother's story would not fit neatly into what I was taught in my history classroom. My grandmother's story left me torn, conflicted and confused, and I still am all of these.

When the interview started, I was angry, resentful and even hated everything that every Black African person had to endure under apartheid. That is how I felt based on what I was taught in my history lessons. As a Grade 12 learner to me all White people were bad, and all Black people endured pain and suffering. This is what I hoped my grandmother would echo, but she did not have one bad thing to say about her life under apartheid. However, I was left in amazement: "How could you not be angry, I am sure you must feel some umbrage towards everything you went through?", I asked her. My grandmother throughout the interview, had no bad thing to say about any families that she worked for. I found it strange that she did not feel any resentment or anger, and was able to clarify why she did not feel any anger. In her words, "Mtanami, the apartheid system was that a system, the families I worked for were people, people that considered my feelings, and made sure that my children were well looked after. How could I hate people that assisted me?"

There was one family in particular that held a special place in my grandmother's heart, the family she worked for, during the period of 19671976, in La Lucia (see Image 3). During the oral history interview, this was the family she referred to the most, the family that she regarded as family.

Now why would my grandmother say this? Possibly the reason could be found in her relationship with her employer from La Lucia who she regarded as "family". With the assistance of my grandmother's employee (Image 3), a four-room house, which offered much better living conditions, was secured. The four-room houses consisted of two bedrooms, a kitchen and a lounge. However, the housing situation was not the only assistance that my grandmother received from her employer. Since my grandmother "lived in" and only returned home during weekends, she would take home all kinds of books for my mother and aunt to read. My mother always states that this is how she learnt to read and write. This support contributed to my mother finishing matric in 1975 and going on to study Social Work at the University of Zululand, where she obtained her Honours Degree in Social Work. Because of my grandmother's employer and the constant giving of books, my mother, Daphne Mbokazi, adopted a love for reading and learning and wanting to change her situation. She had an urge to become better and move-up in life. Hence, whenever my mother looks at the photo (Image 3) she is always filled with gratitude for my grandmother's employer. Additionally, my grandmother's employer allowed her to sell "homemade beer" from their home, to the other domestic workers and gardeners who lived or worked in the area. Although this was not allowed by law, my grandmother's employer allowed her to do so anyway.

This interview, happened more than ten years ago but I still remember her voice, her words and her calmness. I suppose, if all you have known was the apartheid system, some people choose not to fight it and choose to settle and make the most of the life given to them. However, what really irked me was that my grandmother, and she referred to it throughout the interview, as a failed system, was the failed attempts post-1994 to get her dispossessed land returned.

Thinking about and living with my grandmother's story

As a learner being taught the official narrative of apartheid, left me confused as different perspectives of apartheid, which excluded the unofficial views that depict some of the positives that my grandmother had informed me about, were not presented. Consequently, what was revealed to me during the interview left me confused, in disbelief and although it might sound strange, grateful. During the interview my grandmother proclaimed that apartheid was "not as bad as they made it to be". Whenever I thought of these words, I have to wonder ... how could she say "not as bad as what I was taught within the classroom" by my very competent history teacher? Who was she referring to when she said "they"? For a good ten years after the interview with my grandmother, when people spoke about how bad apartheid was, I usually did not comment, nor did I want to voice what was told to me by her. I feared that if I did, people would think I was in favour of apartheid. So, where did I stand? This contradiction between official and unofficial history created much confusion and conflict within me as my grandmother's "historical truth" did not make sense to me and definitely did not match the official truth I learnt about in history and what I saw while living in Kwa-Mashu. I had after all explained to her that I was waiting for a perspective that would support what was taught within the history classroom. When this did not happen, I was initially critical of what I was taught within the history classroom, and I had questions about historical voices that were muted. This is because the perspectives I were taught had omitted my grandmother's voice. I questioned what ideologies the textbook as the programmatic curriculum was promoting which made me speculate where the unofficial narratives were within the curriculum. It made me question where my grandmother's voice was. However, despite my scepticism I decided to become a history teacher.

In reflecting on my grandmother's story over time I realized that it is difficult to unlearn what I was taught within my history classroom, and its it is equally difficult to ignore that Black Africans endured tremendous pain and suffering during the apartheid regime. However, my grandmother's story made me hate the apartheid past less, I no longer feel the bitterness or resentment that I used to feel. I am even grateful for the assistance my grandmother received from the people she has worked for and also take cognisance of my grandmother's words that "it was a system and we had to live in it, a system that can never be erased or forgotten." These words are especially sobering to me as they provided me with historical distance to reflect on the troubled past that I must teach. However, I will never quite be able to eradicate my grandmother's story as it is, despite her not wanting to say so, part of the apartheid era history of forced removals and having to carry a dompas and being patronised by her well- meaning White employers. Seeing the bigger picture has partially silenced my grandmother's story but it remains in my head as someone who now has to teach the official history as found in the curriculum and textbooks and my grandmother's voice constantly reminds me that there is more than one perspective and that unofficial history is important. Hence, I find solace in Lieberman (2006,) who reasons that to understand the paradox of competing histories (conflicting perspectives), it is useful to look closely at national narratives and then to analyse the role of national narratives in generating conflict and disharmony among people.

In conclusion, I was grateful, by means of this article, to reflect, recall, ponder and evaluate my experiences as they relate to unofficial and official history as they relate to apartheid and forced removals (Freese, 2010). As argued by Zwozdiak-Myers (2012), teachers who are keen to expand their professional practice are persistently asking questions which motivates commitment to unceasingly learn and create or find new ideas. Hopefully I will keep on doing so.

References

Ball, SJ 1994. Education reform: A critical and post structural approach. British Journal of Educational Studies, 43(2):221-223. [ Links ]

Cousins, B 2016. Land reform in South Africa is sinking. Can it be saved? Paper presented to Nelson Mandela Foundation. [Online]. Available at https://www.nelsonmandela.org/uploads/files//Land_law_and_leadership_-_paper_2.pdf. Accessed on 14 June 2019. [ Links ]

Department of basic Education, Republic of South Africa. 2011. Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS): Further Education and Training, 10-12. [ Links ]

Dlamini, SI 2016. Transforming local economies through land reform: Political dilemmas and rural development realities in South Africa. Unpublished PhD thesis. Kwazulu-Natal: UKZN. [ Links ]

Freese, AJ 2006. Reframing one's teaching: Discovering our teacher selves through reflection and inquiry, Teaching and Teacher Education, 22:100-119. [ Links ]

Gee, JP 2001Literacy, discourse, and linguistics: Introduction and what is literacy? In E Cushman, E Kintgen, B Kroll, & M Rose (Eds.), Literacy: A critical sourcebook:525-544. Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martin's. [ Links ]

Hanekom D, 1998. Cabinet paper on agricultural sector: Opportunities and challenges. Unpublished Manuscript. [ Links ]

Hall, R 2004a. Land and agrarian reform in South Africa: A status report 2004. Cape Town: Programme for Land and Agrarian Studies, University of the Western Cape. [ Links ]

Kaye, H 1996, Why do ruling classes fear History & other essays. London: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Kloppers HJ and Pienaar GJ 2014. The historical context of land reform in South Africa and early policies. PER 17(2) Available at http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1727-37812014000200004. Accessed on 1 May 2019. [ Links ]

Lieberman, B 2006. Nationalist narratives, violence between neighbours and ethnic cleansing in Bosnia-Hercegovina: A case of cognitive dissonance? Journal of Genocide Research 8(3):299. [ Links ]

Lowis, P 1995. Die jongste nuus van Suid-Afrika. Cape Town: Leo Boeke. [ Links ]

Mkhabela, Z 2018. History teachers' views in making the subject compulsory. Unpublished PhD thesis. Kwazulu-Natal: UKZN. [ Links ]

AS Mboakazi (Grandmother), personal interview, Z Mkhabela (Researcher), October 2009. [ Links ]

South Africa. Department of Land Affairs 1996a. Our land: Green paper on South African land policy. Pretoria: DLA. [ Links ]

South Africa. Department of Land Affairs 1997. White Paper on South African Land Policy. Pretoria. [ Links ]

Thompson, L 1995. History of South Africa. New Haven, CT: Yale University. [ Links ]

Waldo, A 1991. Apartheid the facts. Kent: A. G Bishop and Sons. Ltd. [ Links ]

Zwozdiak-Myers, P 2012. The teacher's reflective practice handbook, London in New York: Routledge. [ Links ]