Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Yesterday and Today

On-line version ISSN 2309-9003

Print version ISSN 2223-0386

Y&T n.20 Vanderbijlpark 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2223-0386/2018/n19a6

ARTICLES

The utilisation of a Mobile Phone Forum on the Winksite application in the teaching and learning of History: a case study of Pre-service Teachers at Makerere University

Dorothy Kyagaba SebbowaI; Paul Birevu MuyindaII

IMakerere University. dsebbowa@cees.mak.ac.ug

IIMakerere University. mpbirevu@cees.mak.ac.ug

ABSTRACT

The teaching and learningprocess is becoming a big challenge at Higher Education Institutions in Sub-Saharan Africa. This is mainly due to the constraints created by the liberalisation of university education and the implied surge in student numbers. In the area of History education particularly, the challenge of large student numbers has forced lecturers to predominantly use behaviourist teaching methods such as lecture and recitation. These methods are characterised by constrained dialogical conversations between lecturers and students, memorising of History facts, dates and limit students' capacity to think historically, which in turn compromises the quality of learning about the past. This article argues for the use of Mobile phone forums as lenses from the present that afford dialogical construction of meanings about the past. A qualitative approach with a case study design was used limited to pre-service teachers (students) at the Makerere University, Uganda. A Critical Discourse Analysis was used to analyse the qualitative data obtained from the students' engagement on the Mobile phone forum by means of the winksite application. The key research findings demonstrated that mobile phone forums enhance interactions between lecturers-students, students-students as a helpful precondition for collaborative learning and reflection about the human past. Conclusions was drawn with a recommendation for History educators to embrace mobile phone forums as a sustainable innovation at the African higher educational context with a potential to enhance dialogical conversations between the past the present and the anticipated future.

Keywords: Critical Discourse Analysis; History teaching and learning; Interactivity; M-Learning; Mobile phone forums; Winksite application.

Introduction

Quality teaching and learning requires every student to become actively engaged in classroom activities. However, this may not be ably realised with large class sizes albeit limitations of lecturers' access to students and inadequate monitoring of student learning. The challenge of large student numbers forces lecturers to engage with methods of teaching like lecture-storytelling and chalk and talk during History education classes. These methods emphasise memorising of facts (Savich, 2009), limit capacity to think historically (Harris & Girard, 2014) and prohibit teacher-student interactions (Anderson, 2008) which in-turn compromise the quality and innovativeness of History education (Sebbowa, 2016). Such pedagogical constraints among others are reported to be the norm in the vast majority of large class sizes in Sub-Saharan Africa at the primary and secondary levels (Nakabugo, Opolot-Okurut, Ssebunga, Maani, & Byamugisha, 2008; O'Sullivan, 2006) and at higher education in universities (Bollag, 2003; Bunoti, 2011; Tibarimbasa, 2010). Embracing the affordances of mobile phone forums Educational Technologies for their perceived pedagogical value is viewed as an potential of bridging the gap between History educators and students in cases of large class sizes (Chu, Capio, van Aalst, & Cheng, 2017; Nakabugo et al., 2007). Moreover, mobile phone forum technologies have proved to be effective, affordable, sustainable and empower today's new generation of students with knowledge and skills at higher educational institutions in Sub-Saharan Africa (Ng'ambi, 2006; Muyinda, 2007; Muyinda, Mayenda, & Kizito, 2015; Oluwatobi & Olurinola, 2015; Kallisa & Pichard, 2017). The aim of the article is to investigate the utilisation of a mobile phone forum in the teaching and learning of History at higher education contexts, particularly at the Makerere University in Uganda.

Mobile phone technologies in pedagogy

The wide adoption of mobile devices and Web 2.0 applications has created new ways of learning through interaction and communication and are widely adopted and integrated in the lives of today's students (Nordmark & Milrad, 2012). Mobile phone diffusion, capability, sustainability and portability are making them the number one companion for the Sub-Saharan African Higher Educational context (Traxler, 2007; Muyinda et al., 2015; Kaliisa & Picard, 2017). The education sector is using them to extend learning support to students at different contexts in what is now called mobile learning (Sandnes & Talberg, 2004; Seipold, 2014, Oluwatobi & Olurinola, 2015). Mobile learning or m-learning is any form of learning that happens when mediated through a mobile device (Herrington, Herrington, Mantei, 2009) such as mobile phones, portable digital assistants (PDAs) and Ipads (Kaliisa & Picard, 2017). Recent researchers have characterised m-learning as taking place when the student is not in a fixed physical learning environment but in an informal context ( Koole, 2009; Rambe & Bere, 2013; Oluwatobi & Olurinola, 2015; Kaliisa & Picard, 2017). Mobile phone technologies are best viewed as mediating tools enhancing mobility of learning processes, of contexts and of expectations (Seipold, 2014; Sharples, 2006; Traxler, 2009; Van der Merwe & Horn, 2018).

The idea of embracing mobile technology into the pedagogical process is an established idea that has been in existence for over 20 years. Higher Education Institutions worldwide, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa (Kaliisa & Picard, 2017), are implementing various educational applications focusing on mobile phone technologies that allow lecturers and students to work freely anywhere at any time (Sandnes & Talberg, 2004; Muyinda et al., 2015). According to Ng'ambi, (2006); Kajumbula, (2006); Oluwatobi & Olurinola, (2015), most students who own mobile phones, are connected most of the time and are communicatively competent with Short Message Services (SMS). Thus, the obvious advantage of mobile phones is their low relatively prices, wide availability, portable size, reliability, re-chargeable battery power, internet accessibility and ubiquity. These, among others, have made mobile devices the technology of choice for people who need quick and easy anywhere, anytime learning and communication (Ferry, 2009). Following this background, the authors argue that, given the current surge in student numbers and large size classes reminiscent in Africa Higher Institutions of Learning Educators (Bunoti, 2011; Tibarimbasa, 2010; Oluwatobi & Olurinola, 2015) particularly, Makerere University. History educators might consider aligning the past to the present by exploiting the affordances of mobile phone technologies available to the current generation of learners.

A systematic review of the use of mobile phones at Higher Education Institutions in Africa revealed that an increased student and lecturer collaboration, provides distant communication, increased student participation and engagement (Kaliisa & Picard, 2017). However, Kaliisa and Picard illuminated a significant challenge of integrating Mobile Learning in higher education such as poor technological infrastructure, lack of mobile learning pedagogical skills among lecturers and low adaptation attitudes among students and lecturers. This implies a need for training lecturers and students as "agents of pedagogical change" on the potentials of innovating History Education by using educational technologies such as mobile phones which may possibly change their 'mind-sets' and attitude. Consistently, empirical research indicates that the integration of mobile phone technology in the Makerere University teacher training and distance education programs has the potential to improve the quality of learning (Bakkabulindi, 2011; Kajumbula, 2006; Lubega, Mugisha, & Muyinda, 2014).

Utilising mobile phones in History education

In the recent years there has been a growing amount of research across the globe concerned with integrating mobile technologies in History Education (Akkerman, Admirrall, & Huizenga, 2009; Hadyn, 2013; Makoe, 2013;

Warnich & Gordon, 2015; Van der Merwe & Horn, 2018). Mobile technologies, like the cell phone for instance, have become an indispensable part of the lives of 21st century History students (Warnich & Gordon, 2015). Makoe (2013) postulates that, integrating mobile phone technologies in History education among under resourced rural communities in South Africa is no longer a luxury but a necessity. Yet, the current generations of students crave for interactivity and learning by doing History which might be realised through the potential affordances of the mobile phone forums. Research was carried out on the use of Universal system for mobile communication in secondary schools in Amsterdam. The results revealed that, engaging with mobile phones in receiving, constructing knowledge and participating invoked the students in being active and motivated during History games (Akkerman et al., 2009). Similarly, studies carried out in History classrooms in the United Kingdom indicated that, embracing the potentials of new technologies provides a powerful motivational tool that mediates dialogical conversations between the past and the present (Hadyn, 2011; 2013).

Warnich and Gordon, (2015) carried out a small scale study on integrating cell phone technology and the application Poll Everywhere as a teaching and learning tool among Grade 9 learners in a school History classroom in South Africa. The results revealed that the majority of the History teachers held high perception levels of embracing the use of cell phone technology and Poll Everywhere in the History classroom although most participants singled out data charges and fees as a hindrance to its utilisation. However, there have been notable obstacles in embracing the use of mobile phones in the History classroom. For example, Haydn, (2013) postulated that the major hindrance of integrating new technologies in the teaching and learning process is that History teachers in the United Kingdom fail to find enough time to explore its use. Similarly, Makoe, (2013) and Warnich and Gordon (2015:42) observed that the majority of the History teachers in rural schools in South Africa are concerned about the increased work load and the ban on the use of cell phones in schools citing unethical activities such as cheating, visiting inappropriate websites, 'sexting' and engaging in cyber bullying. Accordingly, Van der Merwe & Horn (2018) revealed that MobiLex (a mobile dictionary afforded by the use of a smartphone or tablet) holds the potential to expand the historical understanding of concepts democracy and nationalism analysed within a historical context at a university setting.

The above-mentioned studies focused on the use of mobile phones in school History (Warnich & Gordon, 2015); among under resourced rural communities (Makoe, 2013); university setting (Van der Merwe & Horn, 2018) focusing on different contexts in the Netherlands, United Kingdom and South Africa. In this article, we investigate the possibility of using the mobile phone forum on the winksite application in fostering interaction between lecturers and students in a History education course at the Higher Education Institution of Makerere University in Uganda.

A Mobile phone forum and the winksite application

A winksite is a mobile application used for teaching and learning and can be viewed from 'anywhere' at 'any time' on a mobile phone technology (Wang & Higgins, 2008). Moreover, winksites allow users to build discussions forums that foster conversations and interactivity between students and lecturers. In the context of this research, the forum on the mobile phone application winksite was used to foster interactions between students and students and lecturers and their students. A forum on the other hand is conceptualised as an online discussion site where people hold conversions in the form of posted messages (Woodland & Hill, 2010). Forums allow students to post messages to the discussion threads, interact and receive feedback from students and instructor and foster deeper understanding towards the subject under study (Woodland & Hill, 2010). Interactivity among students can be immediate by sending an instant Short Message Service (SMS) text message. Interactivity involves communication, participation and feedback. Online interactivity has a potential to create a climate that supports cooperative learning, critical thinking activities, and meaningful tutor-student academic collaboration (Muirhead, 2000; Muyinda et al., 2015). We used the term mobile phone forum to illustrate the "learning space" on the mobile application winksite. The forum on this mobile application was used as a platform to afford student-student, student- teacher as well as student-content interactions reflected via texts/artefacts during a History education course.

An online learning theoretical perspective

An online learning theory as proposed by Anderson (2004) was used as the theoretical lens to explain the limited interaction between lecturers and students. Anderson argues that an effective learning environment affords many modalities of interactions between the three macro components namely students, teachers and content. Anderson and Garrison (1998) present the six typologies of interactions namely: student-student, student-teacher, and student-content, teacher-teacher, teacher-content and content-content interactions that serve as the basis of educational process in an online learning environment. These interactions are described as critical to effective learning and take place when the learning environment is learner-centered, knowledge-centered, assessment-centered and community-centered (Anderson, 2004). In this article, the student-content relationship is reflected when the student accesses content from the forum on the winksite mobile application and responds to the questions through posting comments. Student-student interaction is evident where students read each other's' comments and respond to themselves or construct their ideas based on other students' comments. Teacher-content relationship is illustrated when the teacher posts a topic for discussion on the forum while student-teacher relation is reflected when the teacher/lecturer gives feedback on the comments posed by the students.

An online learning theory further highlights the community or social component of online learning (Anderson, 2004). The interactions on the mobile forum promote a sense of community, social connectivity between the students and students and their lecturer. The level of connectedness among the students results in formation of productive relationships among the history education community members and in collaborative exploration of the subject matter. As suggested by the theory, it is proposed that learning effectiveness in using forums is influenced by human interactions and communication (language) that represents the social practices and the views of students towards forums on the mobile application. Meaningful learning occurs when students are actively engaged in the learning process and working in collaboration with others to accomplish a shared goal (Anderson, 2004).

The History education course at Makerere University in Uganda

The History education course also referred to as History methods, is housed in the History Education Unit (HEU) at the School of Education (SoE), Makerere University, Uganda. Makerere University, SoE is one of the largest teacher training institutions serving Uganda and East Africa at large (Kagoda & Sentongo, 2015). The History education course introduces pre-service History teachers to the general, basic and innovative methods of teaching History to suit the changing needs of the student in the 21st Century. This course is compulsory for all pre-service teachers taking History as one of their teaching subjects. The course encompasses a wide variety of topical issues that range from the philosophy of teaching History, using sources as evidence to teach History, an introduction to traditional and emerging methods of teaching History, designing History curricula, schemes of work and lesson plans, using research and theory to teach History and the integration of educational technologies in History education among others. Neumann (2010) recommends that History education programs ought to provide a clear, systematic understanding of the disciplinary epistemology of historians to shape the thinking of pre-service teachers and simultaneously provide them with effective training of students in the use of primary sources and historical thinking. He continues to argue that, pre-service teachers cannot teach their future learners to do what they cannot do themselves.

The HEU context is faced with challenges of large student numbers with only two lecturers employed to teach over 600 students on day and evening programmes of study. Students registering for History as one of their core subject increased from 300 in 2010-2011 to 500 in 2012-2013, an increase of 60%. By 2015-2020, the number is projected to grow to over 700 (CEES Strategic plan, 2011). This might prohibit students' access to their lecturers, limit interaction and hence orchestrating an inactive face-to-face lecture session. Many a times, students prepare questions before they attend the lecture but they are not always given an equal opportunity to ask those questions because there is not enough time for the lecturer to answer all the questions often in large classes (Muyinda, 2007). Similarly, the lecturer may want to ask students some questions to trigger and foster their thinking but this may not be ably realised in cases of large class size. Large class sizes provide limited or no provision for lecturer-student and student-student interactions which in most cases limit collaborative construction of knowledge and skills in History education. Against this back drop, therefore, the authors test the use of a mobile phone forum winksite with the possibility of mediating online discussions in the History education class. The mobile phone forum provides potential affordances to counter other technical challenges experienced in the process of integrating Educational technologies echoed in the HEU. For example, technical challenges such as; unreliable electric supply; fluctuations internet; very few students owning personal computers and laptops make a mobile phone forum a sustainable alternative in the HEU. In agreement with this, Ng'ambi (2006) and Santer (2013) argue that the challenges in African Higher Education is finding a technology that is affordable, accessible, easily adoptable by novice computer users and environments where electricity and internet connectivity might be limited or unavailable.

The access rate of mobile phones is ever increasing as students have access through shared usage and ownership. For example, Kaliisa and Picard (2017) noted that, some Sub-Saharan Africa countries such as Kenya and Uganda stand at 83% and 65% mobile ownership respectively. In relation to access, mobile phones add the dimensions of 'anywhere and anytime' connectivity due to their mobility and are switched on most of the time. Most lecturers and students at Sub-Saharan African Universities own a mobile phone, are connected most of the time and are conversant with SMS (Kajumbula, 2006; Traxler, 2009 & Muyinda et al., 2015). For example, a study that engaged with the Adoption of the Substitution, Augmentation, Modification and Redefinition (SAMR) Model to assess ICT pedagogical adoption at Makerere University revealed that mobile phones can be physically accessed and utilised by lecturers to support and communicate to their students (Lubega, Mugisha & Muyinda, 2014). Therefore, if mobile phone technologies can be available and easily accessed they may potentially improve the quality of teaching and learning about the past through enhancing dialogical conversations between past, present and anticipated future. However, it is important to note that mobile phones forums can sometimes disrupt students' attention if strict classroom/lecture rules are not stipulated on when and how to use them for pedagogical purposes.

Research methodology

A qualitative case study design was employed bounded by time and context the Makerere University and more specifically the History Education Unit (Yin, 2003; Miles, Huberman, & Saldana, 2014). A qualitative investigation into students' engagement with the forum on the mobile application winksite was followed. This facilitated the examination of the interactions between the teachers and students in the History education class. A sample of 15 students was conveniently drawn from second year History education pre-service teachers. The sampled case study students were invited to join the History education forum accessible on http://winksite.com/sebbowa/sbbbdor001 on a voluntary basis. The 15 sampled case study pre-service teachers were assigned pseudo names, namely: Peter, Godfrey, Lillian, Rebecca, Ronald, Alfred, Gerald, Alice, Babra, Charles, Adam, Chris, Joshua, Mervin, and K004. They were invited and introduced to the History education mobile winksite application. The participants were further oriented through face-to-face interactions and guided on how to engage and interact with the different functional tools on the winksite application and also requested to engage with their phones in case they had further inquiries (see image 1 below). The image shows a screenshot of an interface of the History education mobile application site illustrating the interactive tools available for use on the winksite, namely forums, links, community members and community messages.

In order to access the winksite in Image 1 above, the participants were required to have a mobile phone with blue tooth capability, relatively big screen resolution, good sound capability and phone credit enough to permit them access internet.

Using the mobile winksite application, the lecturer engaged the case study students in a discussion and tasked them to do the following:

Look critically at the picture of slave trade in East Africa given on the winksite mobile application (A slave trade picture had been posted on the winksite).Go to links and listen attentively to the audio recording/podcast on slave trade in East Africa accessible on the URL link http://kiwi6.com/file/d969g154mg (a podcast on Slave trade had been posted)

The participants are then asked to answer the following questions:

What teaching method would you use to effectively teach the content on slave trade in East Africa presented in the podcast? Give reasons for your choice of response?

That said, the authors, further examined student-student interaction with the forum on the mobile application winksite. The specific activity was:

Make a reflection on the importance of using a forum on the mobile application as a way of enhancing the teaching and learning in a history education class. This is illustrated in Image 3 below.

Following the instructions and tasks highlighted above, participants were asked to use the discussion forum on the winksite application to ask questions in case they needed any clarifications. They were then dispersed but asked to use their mobile phones to access the History education mobile application site, engage with the tasks put forward and post comments and reflections on the forum at 'anytime' from 'anywhere.' All their postings and comments were made public. This was done to make it possible for the participants to comment on each other's' postings so as to initiate discussions, negotiations and enhance shared knowledge and skills construction of History meanings.

Data was then collected in terms of responses/texts obtained after students' engagement with the forum on the mobile application winksite. The data from the different questions and response was analysed using the Critical Discourse Analysis as highlighted in the proceeding section.

Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA)

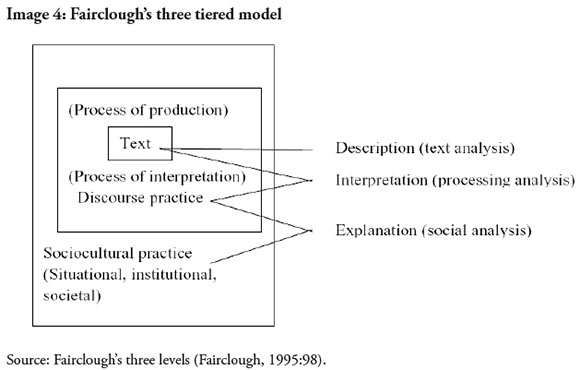

The term 'Critical' in CDA is often associated with studying power relations (Rogers, 2004) while 'Discourse' is the analysis and interpretation of the language in use (Gee, 2014). The analytic procedures depend on what definitions of 'Critical' and 'Discourse', the analyst has taken up as well as his/her intentions for conducting the analysis. CDA is therefore an interdisciplinary approach to the study of discourse that views language as a form of social practice and focuses on the ways social and political domination are reproduced by text and talk. CDA can describe, interpret and explain the relationships and controversies between power/language and Information Communication Technologies (ICTs) in educational institutions (Brown & Yule, 1983). CDA is amply prepared to handle such controversies as they emerge and demonstrate how they are enacted and transformed through linguistic practices in ways of interacting, representing and being (Gee, 2014; Rogers, 2004). It can also be used to demonstrate how ICTs have become deeply involved in the conception and practice of socioeconomic development (Brown, 2012). ICTs work to mediate dialogical conversations through different levels. According to Fairclough, (1989, 1995), analytic procedures include a three-tiered model that includes: description, interpretation, and explanation of discursive relations and social practices at the local, institutional and societal domains of analysis.

In this article, CDA is used to describe the understanding of learning through teacher-student interactivity with the mobile phone forum. This is supported by the fact that, analysing discourse from a critical perspective allows one to understand the processes of learning in more complex ways (Brown, 2012).

Analysis and discussions

This section presents and discusses the qualitative responses (texts and artefacts) drawn from students actual engagement with the forum on the winksite mobile application accessible on http://winksite.com/sebbowa/sbbbdor001 .

Following the study questions reflected in Image 2 above. All participants agreed that different subtopics on slave trade in East Africa can be facilitated using a variety of teaching methods. This is to cater for the diverse learning styles of students in the History education class. For example, in dealing with the sub-topic 'reasons for the rise of slave trade in East Africa' in the History class, learner-centered methods like group discussions, demonstrations and role play which involve learning through active experimentation and reflective historical thinking would be effective, while behaviourist teaching approaches are applicable when students do not have any prior Historical knowledge about the subject under study. This seemingly implies, according to the students, that there is no single best way to teach History but considerations should be given to multiple ways of constructing various History meanings.

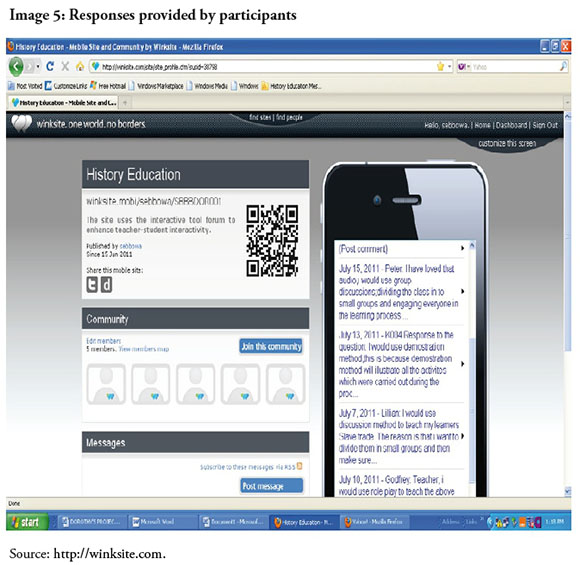

The qualitative artefacts/data are reflected in the postings in Image 5 below by Peter, K004, Lillian and Godfrey.

Following Image 5 above, data were analysed using CDA in reflection of the Description (Text analysis); Interpretation (Processing Analysis); Explanation (Social Analysis).

Text analysis/description: Teaching methodology

A text analysis/description by one of the students (Peter) went as follows:

I would divide my learners into small group discussion and engage everyone in the learning ofhistory. I always prefer learner centered methods ofteaching in my class where as a teacher, I facilitate and guide the learners into constructing knowledge from their previous experiences; I like using interactive teaching methods to create rapport with my students.

This participant expressed confidence when he highlighted a preference for interactive learner-centered methods of teaching. These, he argued, bridged the gap between the students and their lecturers. This is further enhanced by a text/description response by Godfrey who asserted that:

I would use question and answer technique to teach slave trade in East Africa because I want to assess students learning and also create interactivity with them during the pedagogical process.

Interpretation (Processing analysis)

The above qualitative responses demonstrate pragmatism (practical learning) in the pedagogical process (Ng'ambi, 2008). This seemingly implies that, engaging with interactive learner-centered methods in History classes arouses learners' imaginations and ability to see the contemporary events through the lens of the people in the past. The teacher's role shifts to guide and facilitate interpretation and construction of different accounts of the past. Learners' senses of Historical significance are shaped partly by school experiences, contexts and active involvement in shared heritage with the teacher playing a big role in their conception (Harris & Girard, 2014; Mohamud & Whitburn, 2014).

Explanation (Social analysis)

The above sentiments echo that pre-service teachers mainly learn most History topics through constructivist approaches that facilitate active engagement, dialogue and interpretation of history meanings. For example, taking the case of 'slave trade in East Africa' discussed in the preceding section: a need for collaborative participation in the learning process is highlighted aimed at bridging the gap between students and teachers. The above findings concur with Ragland (2014), who argues that History teaching and learning agitates for active learning styles that allow students to act as inquirers and interpreters of the multiple accounts of the past as evidence for Historical understanding. History teachers ought to encourage interactive classroom climate that supports shared construction of History knowledge and skills and student-teacher dialogic conversations about the past (Sebbowa, 2016). Research on the use of constructivist approaches in a History classroom indicates high levels of teacher-student interactions, Historical consciousness, deeper understanding and construction of history meanings (Savich, 2009; Guyver, 2016; Mclean, Cook & Stanley, 2017).

Importantly, participants are leaning towards constructivism which opens the possibility of using mobile phone forums to complement the history meaning making process through sending Short Messaging Services; asking and responding to each other's questions as well as listening to recorded speeches and videos. This seemingly implies facilitation of a formal and informal endless process of learning History in and outside the classroom enabled by affordances of a mobile phone. These constructivist approaches blended with the use of ICT tools particularly mobile phones and are opposed to passive traditional teaching and learning which is still reminiscent for most current history lessons in Uganda (Takako, 2011; Kakeeto, Tamale, & Nkata, 2014; Sebbowa, 2016).

Responses to the reflection on the importance of using forum on the mobile application as a way of enhancing the teaching and learning in a History education class.

The salient qualitative responses to the reflection question were divided into sub-themes, namely: i) collaborative learning- interactivity and ii) Need for continuous online guidance and direction and subjected to CDA as presented in the proceeding sections.

Text analysis/description: Reflection on the importance of using a forum

Collaborative learning- interactivity

Collaborative learning is reflected in the salient qualitative sentiments given by Peter:

I gained a better understanding of the topic under study after reading other students' posts and comments. I obtained lots of knowledge and skills from the different views and opinions shared by participants and the teacher guided us throughout the processes.

While Godfrey was of the following opinion:

After sharing our experiences on the forums, we obtained a sense of belonging and togetherness which forced us to form mobile discussions groups that have been really helpful.

Interpretation (Processing analysis)

The above views highlight the fact that, knowledge and skills about the past can be acquired through reading other students' posts and comments on the mobile application forum. The collaborative interpretation of historical meanings implied that learning can take place through sharing knowledge and obtaining views and opinions of other participants. The use of an online forum- enhances shared negotiations and interpretations of historical meanings where students are actively engaged in the pedagogical process (Sebbowa, et al., 2014; Mclean et al., 2017).

Mobile phone forum provide a platform for a fusion of horizons between the past and present where students as representatives of the present attach meaning to the past events (slave trade in East Africa). Seemingly implying that History education then becomes a dialogical process between studentstudent, student- teacher where the teacher ceases to be the epitome of knowledge but a facilitator of Historical knowledge. Collaborative learning involves a process of learning from each other in a community breeding into deeper exploration of History subject matter. Learning is achieved through a reflective process where students send a comment or question on a mobile forum and receive feedback from fellow students as the teacher directs the learning process. The interaction is mutual and reciprocal, with learning and performance as goals rather than simply information delivery.

Explanation (Social analysis)

The above discourse postulates that, with this mobile communication, learning may occur outside traditional school hours as students participate in collaborative activities, like reading and responding to peer posts at 'anytime', 'anywhere'. Because contexts in mobile learning can be situationally constructed any time, any place, schools and classrooms lose the central position as the only place for learning in the formalised learning process; other places or spaces be it a swimming pool or chat room become relevant places for learning (Seipold, 2014:41). According to Anderson (2003), the interaction in the online forum promotes a sense of community and social connectivity between the learners and instructors. The level of connectedness among students results in formation of productive relationships among the class members and in collaborative exploration of history subject matter. Mobile online forums increase student-student, student-teacher relationships in a collaborative learning environment about cultural heritage in history (Nordmark & Milrad, 2012). Similarly, recent researchers have proposed a model for framing online learning that highlights the social interaction-social technology intersection as a key aspect in affording a group of learners to access multiple materials and learn from 'anywhere' at 'anytime' (Koole, 2009; Rambe & Bere, 2013). Using mobile phone forums encourages students to take initiative in expressing themselves and sharing information with others.

Students become co-producers of knowledge through collaborative knowledge sharing and production. Mobile phone forums therefore have the potential to enable students to take initiative in expressing themselves as shared co-producers of multiple accounts of the past while citing evidence. Furthermore, all participants indicated a need for continuous online guidance.

Text aAnalysis/description

Need for continuous online guidance and direction

Saliently Rebecca commented:

I was at home and I got hold of my phone to access the forums on the mobile application but in the process I got confused and lost a sense of direction because there was no one to ask.

While Peter expounded that:

I was a bit stuck with accessing the forums on the mobile application; I kept on calling another student (Godfrey) to help me get there. I think training on access and use of the forums is very essential if they are to be a success in the pedagogical process.

Interpretation (Processing analysis)

The participant uses a persuasive phrase to encourage educators to continuously guide the learning process. There is need for continued educator guidance and scaffolding if successful mobile learning is to be achieved. More often, students loose direction if the teacher does not focus the learning process basing on the objectives of the lesson. The lack of both verbal and visual cues in the online forum environment can cause misunderstanding between the lecturers and the students and among students (Dawson, Preece, & McLoughlin, 2003). Educator guidance and direction while engaging with mobile phone forums is very crucial as it affords students a multi-dimensional interpretation of history with informed constructed accounts of the past. Notably, students have issues with the costs and taxes levied on using mobile phone internet usage while others still own low end phones that are in most cases not internet enabled.

Explanation (Social analysis)

Sentiments highlighted in the preceding section indicate that participants look to the educators to provide direction through the mass of messages and to provide encouragement to start using the most relevant material (Salmon, 2002). Although social interaction may be a very helpful precondition, high levels of learning depend on structure, design and leadership are provided in form of facilitation and direction (Anderson, 2003). This implies that online educators have to constantly play their role of providing and scaffolding online learning activities so as to sustain interest and motivate learners. Ludwig-Hardman & Dunlap (2003) in Thorpe, (2001) make a recommendation for a student support programme with three interrelated elements; i) Identity - the learner has the opportunity to interact with learner support services personnel on a one-to-one basis; ii) Individualisation - the interaction that the learner has with learner support services is individualised based on the specific needs and goals of the learner; and iii) Interpersonal interaction - the interaction is mutual and reciprocal, with learning and performance as goals rather than simply information delivery. These three elements are important in providing direction to the student during the teaching and learning process.

Conclusion

A mobile phone forum on the Winksite application enhance dialogical conversations between lecturers-students, students- students as a helpful precondition for collaborative learning and reflection about the human past. Given that mobile phone technologies have been found appropriate and are sustainable at the Higher Education African context. The authors suggest that educators, particularly History educators, stick to technologies that can be sustained in their contexts. For example, students can use their mobile phones to text their history comments and questions to the lecturer through a given code/phone number which is cheap and does not require any kind of internet connectivity. However, as noted in the discussion above, a significant challenge of loss of direction and guidance during online and offline pedagogical 'spaces' was observed. This implies that, if mobile phone forum technologies are to be fully integrated within History education, technical support should be provided and continuous lecturer- student and student-student guidance and scaffolds should be availed to re-orient and focus the integration of mobile technologies in the pedagogical process.

References

Akkerman, S, Admirrall, W, & Huizenga, J 2009. Storification in History education: A mobile game in and about Medieval AAmsterdam. Computers & Education, 2(52): 449-459. [ Links ]

Anderson, T 2003. Modes of interaction in distance education: Recent developments and research questions. In: M Moore & G Anderson (eds.). Handbook of distance education. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Anderson, T 2004. Towards a theory of online learning. Theory and Practice of Online Learning, (2):109-119. [ Links ]

Anderson, T (ed.) 2008. The theory and practice of online learning. Athabasca: University Press. [ Links ]

Anderson, T & Garrison DR 1998. Learning in a networked world: New roles and responsibilities. In: C Gibson (ed.). Distance learners in Higher Education. Madison, WI: Atwood. [ Links ]

Bakkabulindi, F 2011. Individual characteristics as correlates of the use of ICT in Makerere University. International Journal of Computing and ICT Research, 2(5):38-45. [ Links ]

Bollag, B 2003. Improving tertiary education in Sub-Saharan Africa, things that work. In: A Report on regional training conference. Accra, Ghana. [ Links ]

Brown, C 2012. University students as digital migrants. Language and Literacy, 14(2):41-61. [ Links ]

Brown, G, Gillian, B & Yule G 1983. Discourse analysis. Cambridge: University Press. [ Links ]

Bunoti, S 2011.The quality of higher education in developing countries needsprofessional support. In: 22nd International Conference on Higher Education. Available at http://www.intconfhighered. org/FINAL%20Sarah%20Bunoti. Accessed on 3rd December 2018. [ Links ]

CEES Strategic plan, 2011. Makerere University, College of Education and External Studies Strategic plan, Kampala. Available at https://pdd.mak.ac.ug/docs/strategic-plans/colleges/CEES-Strategic-Plan. Accessed on 3rd December 2018. [ Links ]

Chu, SKW, Capio, CM, Van Aalst, JCW & Cheng EWL 2017. Evaluating the use of a social media tool for collaborative group writing of secondary school students in Hong Kong. Computers & Education, 110:170-180. [ Links ]

Dawson, P, Preece, D & McLoughlin L 2003. From Essex to cyberspace: Virtual organisational reality and real organizational virtuality; labour & industry. A Journal of Social and Economic Relations of Work, 14(2):17-89. [ Links ]

Fairclough, N 1989. Language and Power. London: Longman. [ Links ]

Fairclough, N 1995. Critical discourse analysis. New York: Longman. [ Links ]

Ferry, B 2009. Using Mobile Phones to enhance teacher learning environment education. In: J Herrington, A Herrington, J Mantei & B Ferry (eds.). New Technologies, new pedagogies, mobile learning in higher education. Faculty of Education Papers (Archive), University of Wollongong, Australia. [ Links ]

Gee, J 2014. An Introduction to discourse analysis: Theory and method. London and Newyork: Routledge. [ Links ]

Guyver, R (ed.) 2016. Teaching History and the changing national state: Transnational and international perspectives. London: Bloomsbury. [ Links ]

Harris, LM & Girard, B 2014. Instructional significance for teaching history: A preliminary framework. Journal of Social Studies Research, 38(4): 215-225. [ Links ]

Haydn, T 2011. The changing form and use of textbooks in the history classroom in the 21st century: A view from the UK. In: E Erdmann, L Cajani, AS Khodnev, S Popp, N Tutiaux-Guillon & GD Wrangham (eds.). Analyzing Textbooks: Methodological issues. Yearbook of the International Society for History Didactics. Schwalbach: Wochenschau Verlag. [ Links ]

Haydn, T 2013. Using new technologies to enhance teaching and learning in History. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Herrington A, Herrington, J & Mantei, J 2009. Design principles for mobile learning. In: J Herrington, A Herrington, J Mantei, I Olney & B Ferry (eds.). New technologies, new pedagogies: Mobile learning in higher education. Faculty of Education (Archive), University of Wollongong, Australia. [ Links ]

Kagoda, AM & Sentongo, J 2015. Practicing Teachers' perceptions of teacher trainees: Implications for teacher education. Universal Journal of Education Research, 3(2):148-153. [ Links ]

Kajumbula, R 2006. The effectiveness of Mobile Short Messaging Services ( SMS) technologies in the support of selected distance education students of Makerere University. Available at http://cees.mak.ac.ug/effectiveness-mobile-short-messaging-service-sms-technologies-support-selected-distance-education. Accessed on 20 October 2018. [ Links ]

Kakeeto, MB, Tamale, MB & Nkata, J 2014. The secondary school History curriculum objectives and their influence on national integration: Stakeholders perspective. International Journal of Innovative Social & Science Education Research, 2(1): 46-55. [ Links ]

Kaliisa, R, & Picard, M 2017. A systematic review on mobile learning in Higher Education :The African Perspective. The Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology ,16(1):1-18. [ Links ]

Koole, ML 2009. A model for framing mobile learning. Mobile Learning:Transforming the Delivery of Education and Training, 1(2):25-47. [ Links ]

Lubega, TJ, Mugisha, A & Muyinda, PB 2014. Adoption of the SAMR model to asses ICT pedagogical adoption: A Case of Makerere University. International Journal of E-Education, E-Business, E-Managementand E-Learning, 4(2):106-115. [ Links ]

Ludwig-Hardman, S & Dunlap, JC 2003. Learner support services for online students: Scaffolding for success. The International Review ofResearch in Open and Distributed Learning, 4(1):1-15. [ Links ]

Makoe, M 2013. Teachers as learners, concerns and perceptions about using cell phones in South African rural communities. In: Z Berge & L Muilenburg (eds.). Hand Book for Mobile Learning. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Mclean, LR, Cook, SA & Stanley, TJ 2017. Historical thinking, historical consciousness. Canadian Journal of Education, (1):1-5. [ Links ]

Miles, M, Huberman, M & Saldana, J 2014. Qualitative data analysis, a methods source book, 3rd edition. London: Sage Publication Ltd. [ Links ]

Mohamud, A & Whitburn, R 2014. Unpacking the suitcase and finding history: Doing justice to teaching of diverse histories in the classroom. The Historical Association, (154):40-46. [ Links ]

Muyinda, B 2007. M-Learning: Pedagogical, technological and organization types and realities. Campus- Wide Information Systems, 2(24): 97-104. [ Links ]

Muyinda, B, Mayenda, G & Kizito, J 2015. Requirements for seamless collabortive & cooperative mlearning system. Available at http://cees.mak.ac.ug/requirements-seamless-collaborative-and-cooperative-mlearning-system-1. Accessed on 20 September 2018. [ Links ]

Nakabugo, M, Opolot-Okurut, C, Ssebunga, C, Ngobi, D, Maani, J, Gumisiriza, E & Bbosa, D 2007. Instructional strategies for large classes: Baseline literature and empirical study of primary school teachers in Uganda. Report of the proceedings of the Africa-Asia University dialogue for Basic Education, pp. 15-17. [ Links ]

Nakabugo, MG, Opolot-Okurut, C, Ssebunga, CM, Maani, J & Byamugisha A 2008. Large class teaching in resource constrained contexts: Lessons from reflective research in Ugandan primary schools. Journal of International Co- Operation in Education, 11(3): 85-102. [ Links ]

Neumann, D 2010. What is the text doing? Preparing pre-service teachers to teach primary sources effectively. The History Teacher, 43(4): 489-511. [ Links ]

Ng'ambi, D 2006. ICT and economic development in Africa: The role of higher education institutions. In commissioned as background paper to the University Leaders' Forum by the Partnership for Higher Education in Africa, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Ng'ambi, D 2008. A Critical discourse analysis of students' anonymous online postings. International Journal of Information and Communication Technology Education, 4(3):1-39. [ Links ]

Nordmark, S & Milrad, M 2012. Mobile digital story telling for promoting creative collaborative learning. In: Proceedings 2012 Seventh IEEE International Conference on Wireless, Mobile and Ubiquitous Technology in Education, IEEE, 2012, pp.9-16. [ Links ]

Oluwantobi, S & Olurinola, O 2015. Mobile learning in Africa: Strategy for educating the poor. Available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=2606562. Accessed on 28th November 2018. [ Links ]

O'sullivan, M 2006 Teaching large classes: The international evidence and discussion of some good practices in Ugandan practices in Ugandan primary schools. International Journal of Educational Development, 26(1):24-37. [ Links ]

Ragland, RG 2014. Preparing secondary History teachers : Implementing authentic instructional strategies during pre-service experiences. Social Studies Research and Practice, 9(2): 48-67. [ Links ]

Rambe, P & Bere A 2013. Using mobile instant messaging to leverage learner participation and transform pedagogy at a South African University of Technology. British Journal of Educational Technology, 44(4): 544-561. [ Links ]

Rogers, R 2004. Setting an agenda for critical discourse analysis in education. In: R Rogers (ed.). An introduction to critical discourse analysis in education. Mahwah, NJ:Eribaum. [ Links ]

Salmon, G 2002. The five-stage framework and etivities. In: G Salmon. E-tivities : The key to active online learning. United Kingdom: Kogan. [ Links ]

Sandnes, FE & Talberg, O 2004. Mobile phones in the lecture theatre-using wireless technology as a pedagogical aid. In: W Aung (ed.). International Engineering education and research-2004: A Chronicle of Worldwide Innovations. USA: Begell House. [ Links ]

Santer, M 2013. A model to describe the adoption of mobile internet in Sub-Saharan Africa. Unpublished PhD thesis. University of South Thampton. [ Links ]

Savich, C 2009. Improving critical thinking skills in History. Available at http://search.ebscohost.com/login. Accessed on 28th November 2018. [ Links ]

Sebbowa, D 2016. Towards a pedagogical framework for construction of historicity: A case of using Wikis among pre-service teachers at Makerere University. Unpublished PhD Thesis. University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

Sebbowa, D, Ng'ambi, D & Brown, C 2014. Using Wikis to teach History education to 21st century learners: A hermeneutic perspective. Critical Studies in Teaching and Learning, 2(2): 24-48. [ Links ]

Seipold, J 2014. Mobile learning: Structures, concepts and practices of the British and German. Mobile Learning Discussion from a Media Education. Available at: www.medianpaed.com. Accessed on 28th November 2018. [ Links ]

Sharples, M (ed.) 2006. Big issues in mobile learning. Report of a workshop by the Kaleidoscope Network of Excellence Mobile Learning Initiative, University of Nottingham, UK. In: P Thornton & C Houser, 2005. Using mobile phones in English Education in Japan. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 21(3): 217-228. [ Links ]

Takako, M 2011. History education and identity formation: A case study of Uganda. [ Links ]

Claremont Mc Kenna College. Available at http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/197. Accessed on 28th November 2018. [ Links ]

Tibarimbasa, A 2010. Factors affecting the management of private universities in Uganda. [ Links ]

Makerere University. Available at http://mak.ac.ug/documents/Makfiles/theses/Tibarimbasa_Avitus.pdf. Accessed on 28th November 2018. [ Links ]

Traxler, J 2009. Current state of mobile learning. Transforming the Delivery of Education and Training, (1):9-24. [ Links ]

Van der Merwe, MF & Horn, K 2018. Mobile concepts in a mobile environment: Historical terms in LSP lexicography. Yesterday&Today,(19):17-34. [ Links ]

Wang, S & Higgins, M 2008. Mobile 2.0 leads to a transformation in MLearning. International conference on hybrid learning and education. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. [ Links ]

Warnich, P & Gordon, C 2015. The integration of cell phone tehnology and Poll Every Where as teaching and learning tools into the school History classroom. Yesterday &Today, (13): 40-46. [ Links ]

Woodland, W & Hill J 2010. I really get this module! Using online discussion boards to enhance students' understanding of global change. In: S Haslett, D France & S Gedye (eds.). Pedagogy of Climate Change. Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences Subject Centre. [ Links ]

Yin, R 2003. Case study research: Design and methods, 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publication Ltd. [ Links ]