Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Yesterday and Today

On-line version ISSN 2309-9003

Print version ISSN 2223-0386

Y&T n.20 Vanderbijlpark 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2223-0386/2018/n19a5

ARTICLE

Our schools our identity: efforts and challenges in the transformation of the history curriculum in the Anglophone subsystem of education in Cameroon since 1961

Roland Ndille

Centre for Education Rights and Transformation University of Johannesburg. rndille@uj.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The teaching of history in countries that have experienced colonisation has come under serious scrutiny at different times in their history. Worries about the contents of history programmes have been raised by politicians as well as educational technocrats who question the relevance of what is being taught as history to those on the classroom pews. In Cameroon, and particularly for the Anglophone subsystem of education, this debate is far from over despite the fact that the destiny of the country has rested in the hands of those who fought against colonialism for over fifty years now. This paper emanates from the premise that the colonial curriculum did not meet the realities of the new country since 1961. Consequently, there was a consensus of opinion that curriculum reform should focus on the teaching of local and national contents. By adopting the critical Decolonial perspective and living theory methodology the study focuses on history as one of those subjects which was used by the colonial authorities to entrench coloniality (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2013; Marsden, 2013; Rodney, 1982; Fanon, 1963) and was therefore in dire need of postcolonial reform. The study examines the extent to which this has been achieved in the Anglophone subsystem of Education by presenting what was learnt in the colonial history classroom in the British Southern Cameroons between 1916 and 1961. It then goes on to discuss the process of reform in the History curriculum of the Anglophone subsystem of education in Cameroon since independence.

Keywords: Cameroon; Anglophone Subsystem of Education; History curriculum; British Colonial Education; Reform; Transformation; Africanisation; Indigenisation.

Introduction

Recently, The Conversation; an Australian daily newspaper published an article titled "history teaching has moved on, and so should those who champion it!" The paper made reference to the rejection of grants by several universities in Australia, to set up programmes for the award of degrees in Western Civilisation proposed by a renowned research centre (The Conversation, June 6, 2018). This rejection was in response to the criticisms of the centre for privileging Western historical contents in the Australian school curriculum to the detriment of indigenous knowledge. The situation in Australia is similar to that in South Africa where questions of representation in and relevance of History curriculum have made headline news in the past few years (Chisholm, 2005; Ramoupi, 2012; DoBE, 2018; Radio 702 Podcast 22 May 2018). In February 2018, the South African Department of Basic Education (DoBE) Ministerial Task Team on the History curriculum published its report (DoBE, 2018) to which Angie Motshekga, the Minister outlined that the major issue with the history curriculum centred on whether what is taught and the way it is taught "meets our objectives of.. .defining ourselves much more clearly as Africans" (quoted in Radio 702 Podcast, 22 May 2018).

Like in South Africa in the past two decades, the need to solve the incongruence between colonial education and African realities motivated early postcolonial curriculum reforms in most African countries (Bangura, 2005; Kwabena, 2006). In 1962, Amadou Ahidjo, the pioneer president of Cameroon confirmed that the organisation, methods and curricula of the education system which he inherited "was perforce, to a large extent, redolent of the concepts characteristic of our former trustees" (Ahidjo, 1967:9). The president spoke clearly about subjects like History and Geography which he argued "corresponded neither to African reality, nor to our political independence" and instructed planners to "shun all servile importing and transplanting of foreign systems" (Ahidjo, 1967:9).

Based on such directives, educational reform in Cameroon at independence was amongst other things aimed at developing new curricula with emphasis on indigenous/local contents. While there are sources on the history of education in the country with complete or partial focus on the Anglophone subsystem of education, (Ndongko & Tambo 2000; Tambo, 2003; Fonkeng 2007; MacOjong 2008) empirical studies on the transformation ofthe History curriculum has been rare to find. Studies like Tosam (1988), Tambo (2000), Diang (2013) and Ndille (2015) have discussed postcolonial educational transformation without making the question of transformation of the History curriculum a particular point of emphasis. This has made for an inability to say with certainty, the nature of the History curriculum or present with clarity, the extent to which reform towards a local contents History curriculum has been achieved in the country. This study therefore not only investigates transformation within the History curriculum but also focuses on the extent of indigenising the contents and challenges inherent.

The justification for reform towards a predominantly local contents curriculum rests on two premises; (1) as a response to what is going on in Western societies where African history is hardly visible in the school curricula (Connelson, 2000; Hjelden, 2004; Marmer & Sow, 2013) and (2) the understanding of education as the "experience of a living organism interacting with its environment (Peters, 1966); an eternal process of the adjustment to an intellectual, emotional and cultural environment of those concerned and the transmission of what is worthwhile in it to those who become committed to it (Lodge, 1974 in Schofield, 1978:107). As UNESCO defines it, history is a study of how each generation received the culture from the previous one and how they preserved and handed it down to the succeeding generation (UNESCO, 1985:11).

Theoretical and methodological frameworks

The study builds on the Decolonial theoretical perspective which sees postcolonial History curriculum reform as a constituent effort in the decolonisation of the African school systems; a problem which many African states are still grappling with. The Decolonial theory propagates the idea that colonial school contents had hardly been for the benefit of the people ofAfrica (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2013). Instead such contents disrupted African modes of knowing, social meaning-making, imaging, seeing and knowledge production by advancing Eurocentric epistemologies that presented the colonised world "as terra nullius and the people, anima nullius; (as the space of misery, savagery, ignorance and disease) where help was needed; and where everything was subject to experiment" (Grosfoguel, 2011: 6). Such a representation of Africa was false and consequently necessitated curriculum revision at independence.

Methodologically, the study adopts the Living Theory Methodological Framework (Whitehead, 2008). Living theory is a disciplined process of inquiring into the self by the self; thinking about one's own life and work as a practitioner so that one can continue developing oneself, one's work; that of others and by so doing make significant contributions in one's work and society" (Whitehead 2008:104). As a historian, teacher of history and curriculum developer, I find this methodology fitting seeing that issues of relevance in the History curriculum need to be addressed by those in the field of history teaching. The adoption of this perspective also guarantees flexibility in data collection and analysis (Whitehead, 2008) as it advocates "the use of idiosyncratic perspectives while respecting objectivity and research ethics" (Seineart, 1989:92).

This means that, researchers can use any approach that they think would best present their ideas. It therefore enabled me to blend my experience as a history pupil, student, teacher and curriculum reformer in Cameroon with what I found in archival documents and textbooks dealing with History curriculum, syllabus prescriptions, and schemes of work and lesson notes of teachers of the various periods under review. For each officially prescribed textbook and document stating the contents to be taught, I resorted to a manual count of topics and classified in terms of whether they addressed local Cameroonian-based issues, Africa or Europe and the rest of the world. I then presented each category as a percentile of all the contents on the specific document. This enabled me to arrive at an approximately authoritative figure relating to which set of contents dominated the curriculum at each historical period of analysis. In presenting this data, I also used my experiences of history learning and teaching in Cameroon and participation in some professional and ministerial commissions charged with reforming history subject contents. These experiences as London (2002:17) puts it, served as "a kind of weather vane by which we might gauge the direction in which the curriculum reform was blowing."

The colonial History curriculum in British Southern Cameroons: Contents and rational

The history of colonial Cameroon is divided into two phases. Phase one is the German colonial period (1884-1916) and phase two, the British and French colonial period (1916-1961). Following their joint action in ousting the Germans from Cameroon during the First World War, and their failure to agree on the terms of a proposed joint administration (Elango, 2015), Britain and France partitioned the former German colony and established separate administrations. It was only on October, 1, 1961 that the Southern part of British Cameroons voted to acquire independence by reunifying with French Cameroon (Ngoh, 2011). The discussion in this paper does not include what went on in the French administered Cameroons. Emphasis here is on the British colonial History curriculum as one of the systems that needed replacement at independence in 1961. For the sake of convenience, the British decided to administer their sphere of the territory as parts of their colony of Nigeria. Consequently, all educational arrangements in the British sphere of Cameroon were attuned to British policies in Nigeria (Fonkeng, 2007). In terms of education, the philosophy that the British adopted in the Cameroons was adaptation (Jesse-Jones 1925; Bude, 1983). This was based on the 1925 Phelps-Stokes report of their survey of education in Africa between 1920 and 1924 (Jesse-Jones, 1925).

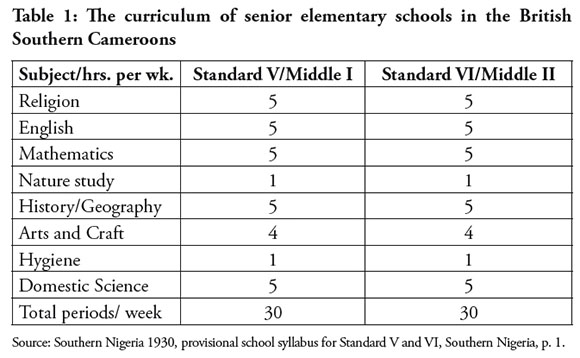

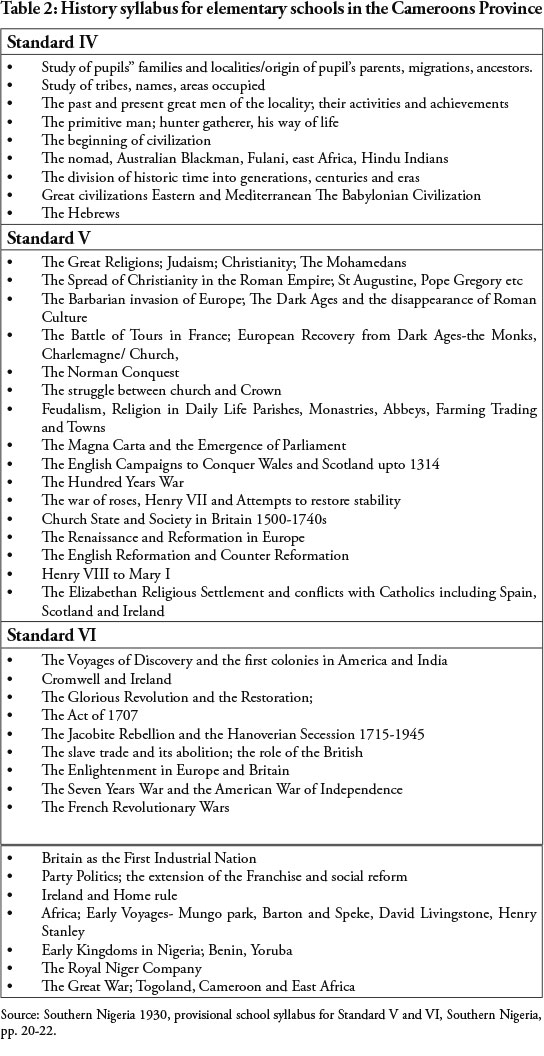

The Phelps-Stokes Commission reported of an educational system dominated by European contents to the detriment of local contents and (for history) proposed that all the illustrative examples for this course should be taken from what the children themselves know and the course should really be one to make explicit the ideas which are implicit in the life that all the children led (Jesse-Jones, 1925:23). The suggestions of the Phelps-Stokes Commission were quickly bought into British colonial education policy in the 1925 Memorandum of Education for British Tropical Africa. It outlined that "education should be adapted to the ... traditions of the various peoples, conserving as far as possible all sound and healthy elements in the fabric of their social life" (Colonial Office, 1925:3) and "preserving all the material and moral development of past years..." (Cameroons, 1925:58). The recommendations which featured in the 1926 Nigerian Education Ordinance applicable in Cameroon from September 1927 meant that the official school syllabuses which were only written in 1930 Table 1 below had to prescribe a local History curriculum of British Cameroon schools. The outcome is presented in Table 2 below.

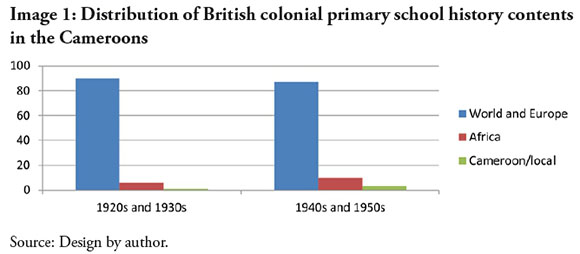

From Table 2 above, one thing is clear; despite the calls for curriculum adaptation, what obtained in subjects like history was a complete opposite of the adaptation philosophy. In history the senior classes began with the study of prehistory; hunters; Paleolithic man and moved to the history of Europe which was in essence, the history of the British Empire; an indication of the fact that curriculum revisions proposed by adaptation did not take place in the history programme. Image 1 below presents the contents in terms of distribution between local Cameroons contents, African based contents and the history of the rest of the world.

At the level of secondary education, Saint Joseph's College popularly called SASSE College, the first secondary school in British Cameroons was opened in 1939 by the Mill Hill Missionaries in Buea, followed by the Basel Mission College at Bali ten years later (Ndille, 2014). While these schools made access to secondary education in the territory possible, a majority of the British Cameroons students were educated in Nigeria (Ndille, 2014). The junior secondary schools first three years like the teacher training centres basically used the adapted syllabus of the senior elementary schools presented on Table 2 above (File Sb/c/1933/1 NAB). For the 4th and 5th years, the curriculum was that prescribed by London Matriculation Overseas School Certificate Examination with emphasis on English both Language and Literature, Mathematics, Science, History and Geography (Nfi, 2014:60).

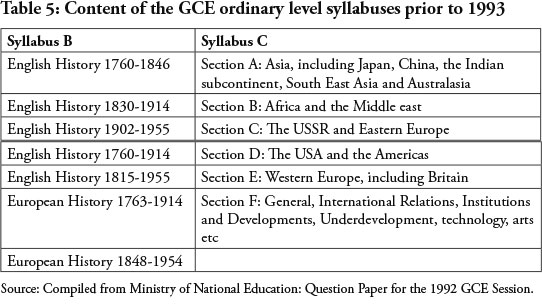

The London Matriculation -Certificate was replaced in 1957 by the West African School Certificate Examination WASCE but the change did not affect schools contents. The examination syllabus for the end of course examination included English History 1760-1846; English History 18301914; English History 1902-1955; English History 1760-1914; English History 1815-1955; English History 1763-1914; European History 17631914 and European History 1848-1954 (National Archive Buea NAB File Sb/g/1958/1). While students were given a minimal choice regarding the sections they could answer, the point to note here is that there was no history of Africa on the examination syllabus less talk of the history of the Cameroons. Until independence, no major contents revision took place in the schools syllabuses.

The prescription of History curriculum contents in Cameroon also had implications for textbook choice. Text books were and probably are still the most widely used resource for the teaching and learning in most schools (Marsden, 2013:1). That is why curriculum documents often ended with suggested textbooks. For the Cameroons, the prescribed history textbooks included: Wells' Outline of History; Van Loon's History of Mankind; Marvin's The Living Past and Bury's Political Ideals. HG Well"s The Outline of History Wells, 1920 for example had forty chapters spanning the origins of the earth and ending with the 19th Century with colonial Africa as a whole, whose schools used it making up no full chapter. This was probably why it was heavily acclaimed by Arnold Toynbee (Toynbee, 1934) and AJP Taylor who had similar views of Africa not constituting any historical part of the world (Awasom & Bojan, 2009).

Chapter seven and eight of Well's History book dwelled on human origins with focus on the Neanderthals Wells, 1920 as if to give the impression of a European cradle of human kind. Although a critique described some of the chapters as "probably laughable to any expert in the field" (Goodreads, 2018:1), the fact remains that pupils and students in Southern Cameroons were immersed with ideas which, while they gave their counterparts in the metropole a superiority complex, left them with a cloak of inferiority.

According to Johnsen (1993:327-328 in Marsden, 2013) textbooks are about the people who influence the educational culture for which they are written. In this way textbook choice for history in the Southern Cameroons took into consideration those authors who fostered the colonial agenda of Britain.

Summarily, looking at the curriculum and the textbooks, one realises that on paper, colonial policy documents gave the impression that Britain was in favour of teaching the local history of Southern Cameroons (Jesse-Jones, 1925; Colonial Office, 1925) but on ground, that was not the case. Why then did Britain not implement adaptation in the History programme? Supporters of the colonial agenda tacitly push forward the idea of resistance and contestation; that Southern Cameroonians, as part of the British colonial empire requested for European contents in the shaping of what counted as valid knowledge in the History curriculum (Ball, 1983; Whitehead, 2005). Attempts to identify issues of contestation and resistance in the colonial archive of the Southern Cameroons did not yield any fruits.

On the contrary, documentary evidence and testimonies presented in this study demonstrate that the principle of resistance and contestation seem more like attempts at historical revisionism. There are many who have presented evidences to demonstrate a colonial imposition of curriculum in different parts of the empire for the sake of subjugation and assimilation (Kwabena, 2006; London, 2002; Marsden, 2013). In fact as early as 1847, the policy goals of the Education Committee of the Privy Council described the African as primitive in need of British civilisation which in turn required an imperial curriculum. Point two of the 1847 Privy Council text talks pejoratively of the need to "accustom the children of these races to habits of self-control and moral discipline;" the need to diffuse a grammatical knowledge of the English language and history as the most important agent of civilisation (Gwei, 1975:97). Point five of the same text insists that school books and other materials of instruction had to strictly teach the mutual interests of the mother country and impart knowledge and skills to the black races for "domestic and social duties" to the metropole (Gwei, 1975:98).

Such goals were never abandoned and confirms Webster's position that British worldwide expansion in the 18th and 19th centuries were an economic and political phenomenon with a strong social and cultural dimension to it (Webster, 2006:7). That is why the 1930 provisional syllabus booklet for the Southern Cameroons actually specified that "emphasis is to be on knowledge of the British Empire, Europe and the Western World (Southern Nigeria Provisional School Syllabus, 1930:2). As late as the 1930s some conservatives in the Colonial Office continued to insist that:

It was outrageous to go on teaching "monstrous superstitions, false history, false astronomy and false medicine. A break must be made by teaching English

language, literature, history, geography culture and values. This is the only way for native territories to enter the modern world by absorbing those British cultural

riches and by being assimilated in so far as it was possible to English values (File Sb/a/1934/2 NAB).

In a syllabus review meeting for Southern Cameroons in 1935, one of the reviewers for history and geography; Mrs Plummer, lamented that she "has never been able to understand why local history is supposed to be taught in the Southern Cameroon." She emphasised that instead of local history, modern topics like the Italian and German unifications and the First World War should be featured on the syllabus (File Sb/a/1934/2 NAB).

These facts put together, counter the resistance and contestation theory and place the colonial history curricula in the Southern Cameroons within the context of colonial imposition. They also indicate that the popularisation of the philosophy of curriculum adaptation was merely a smokescreen behind which Britain hide to perpetuate coloniality of knowledge, and being (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2013), colonial imagination (London, 2002) and social control (Aronowitz, 1992; Popkewitz, 2000). According to London:

Just as the current global world works through a dependence on a global imagination, so did British Empire building engage and depend upon a colonial imagination developedfor, and internalized by the local through curriculum and pedagogic practices. Selection of contents for the interest of the colonizer was the main feature that guided the enterprise (London, 2002:95-96).

Popkewitz (2000) has also argued that, the function of colonial imagination was to fashion colonised people into the seam of a collective narrative and helped them generate conceptions of personhood and identity of Britain as coloniser. This significantly guaranteed social control without the necessity of Britain as the dominant group having to resort to overt mechanisms of domination as in the repressive state apparatus (Aronowitz, 1992). Myers & Myers, (1990) also hold that even if it was not an overt goal to short-change the moral threads of the Africans through the curriculum, the contents of the history lessons which were taught in the colonial school introduced pupils to a new lifestyle which led to the total disregard for local customs and practices and brought about a new generation of Southern Cameroonians who saw themselves as having the mind of Europeans (Freund, 1984). Awasum (2014:18) attests that "we were constantly referred to as British men and [innocently] this made us proud. To Nfi (2014:60) this was a process of "the Anglicisation of the Cameroons".

This policy proved too successful in the Southern Cameroons to the extent that by 1961, when Britain left, knowledge of Cameroon history was trifling and only a negligible number of Southern Cameroonians including most of those in leadership positions had some faint knowledge about the Mandates and Trusteeship systems of colonial administration; about the differences between the British and the French systems of colonial administrations, and the similarities, if any, in the two systems and, above all, about the rights of colonial subjects and the so-called responsibilities of the administering powers. Such issues were expected to feature on the History curriculum of Southern Cameroons as a UN territory, but were never included. Southern Cameroonians were therefore largely ignorant of their own history and geography with the consequence that, almost all studies on the economic viability of the territory by 1961 were undertaken by European anthropologists such as Phillipson, Anderson and Chicks (Ngoh, 2011). Such studies, were only published abroad and were not widely known within the territory. Moreover, the character of the studies was not of the sort which could inspire political consciousness in the Southern Cameroonians. Independence was therefore attained with the people of Southern Cameroons having but a blurred/minimal knowledge of the history of their territory.

The transformation of the History curriculum in the Anglophone former Southern Cameroons subsystem of education after independence in 1961

The independence of Nigeria in October 1960 meant that a decision on the political future of the Trust Territory of the Cameroons which had been administered by Britain as part of their colony of Nigeria had to be made. A plebiscite was organised to this effect on February 11, 1961 with the UN options of the British Cameroons either joining Nigeria or La Republique du Cameroun (the French Administered Cameroon) which had got independence on January 1, 1960. In the plebiscite, the British Northern Cameroons voted to join Nigeria while the British Southern Cameroons voted to join La Republique du Cameroun and a two state Federal government was established. The British Southern Cameroons became the state of West Cameroon while La Republic du Cameroun became the state of East Cameroon. Further state reforms have occurred which affected different levels of education notably in 1972 and 1996 but what is important for us here is that from 1961, state reforms have continued to maintain the bicultural system of government and two subsystems of education based on the British and French colonial heritages; the Anglophone and the Francophone subsystems respectively (Federal Republic of Cameroon, 1961). The discussion on the History curriculum of the various levels of education hereunder relates exclusively to the Anglophone subsystem of education within the context of continuity and change in the erstwhile British Southern Cameroons discussed above.

The transformation of the primary school curriculum since independence in 1961

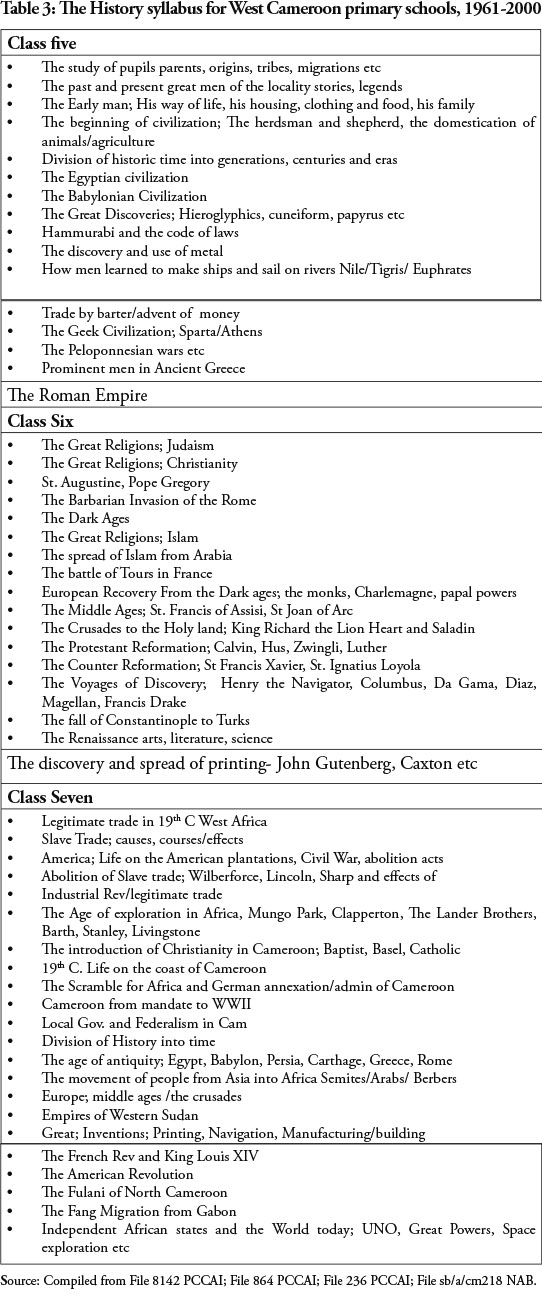

As far as primary education was concerned, the 1961 Federal Constitution provided that primary education was the prerogative of the state governments, while secondary education was placed under the Federal government. On June 19, 1963, the federal government passed Law No. 63/DF/13 of 19/06/63 aimed at structurally harmonising education of the two sectors (Ndille, 2015). The state governments also passed laws regulating primary education in the two states. Regarding primary education, the West Cameroon government passed the West Cameroon Education Ordinance in 1963. The ordinance proposed the revision of the inherited colonial primary school curriculum which they agreed was not linked to the basic realties of independent Cameroon (West Cameroon, 1963). With minimal revision in 1968, the curriculum was in use in the English speaking subsystem of education until 2001. The content is presented on Table 3 below.

Compared to the colonial curriculum, there was not much of a change in the contents of the 1963 curriculum. Since the minor revisions of 1968, much of what was thought in the Anglophone schools between 1961 and the year 2001 reflected what went on in colonial British Cameroons despite their claims for revision. A British technical adviser even confessed that:

In the UK, we are abandoning the attempt to give a synoptic view of world history and are finding it more profitable to allow teachers to select a few significant local history topics and allow the classes to study them thoroughly. It seems unrealistic to try to cover the whole field of history. My suggestions are that primary schools should concentrate entirely on local history, Cameroon History, citizenship and a few aspects of African and world history which have affected Cameroon (File 1842 PCCCAL).

Appeals for the development of a truly Cameroonian history syllabus did not end up in any concrete product. Teachers were expected to critically study the syllabus, propose what was to be eliminated and suggest what was to be included in the curriculum. This was in view of the annual summer history schools which held in the 1960s and 1970s at the Government Teacher Training College Kumba every August (File Sb/a/1979/11 NAB). HR Merkel who had a PhD in history and was serving as History tutor at the Cameroon Protestant College Bali made a proposal to write a History textbook for Cameroon history. Teachers of history in the entire territory were called upon to write the history of their localities so that a harmonised book of that nature would become the springboard for the teaching of Cameroon history. Such efforts were not successful (File 1842 PCCCAL). Education continued to be detached from the society which it was expected to serve and the history subject matter continued to reflect to a great extent, the one adopted by British colonial administration in the 1940s and 1950s.

It must also be mentioned that in 1974, the government had created a centre for curriculum and pedagogic research in Buea called The Centre for Rurally Applied Pedagogy whose mission was to adapt school contents to local Cameroonian realities (IPAR, 1977). The curriculum revisions suggested by the centre actually put emphasis on local history and culture but by the early eighties, less than ten years of its existence, the centre had closed with little of its work having been implemented (Tosam, 1988; Ndille, 2015). So far, curriculum transformation had been carried out by the ministerial departments and by the specialised research centre but none of these seem to have succeeded in implementing a local contents curriculum. The third approach was to call a national education forum in 1995.

From May 22 to 27, 1995 educational stakeholders from all corners of the country assembled in Yaoundé to deliberate on matters relating to the education of the Cameroonian children. Some of the reasons for holding the forum included; the lack of a proper educational policy; the neglect of local and national cultural values; the failure of previous readjustments to consider national realities; the need to consider the socio-political changes that the country had undergone; and the failure of education to attribute a high value to local cultures and heritage (Ministry of National Education, 1994). The political objectives of the conference stressed amongst other things "the adoption of a truly Cameroonian educational system which will value national realities and instil in the learners a .. .love for the fatherland.. .and define the place of national culture and heritage in the educational system" (Ministry of National Education, 1995:3).

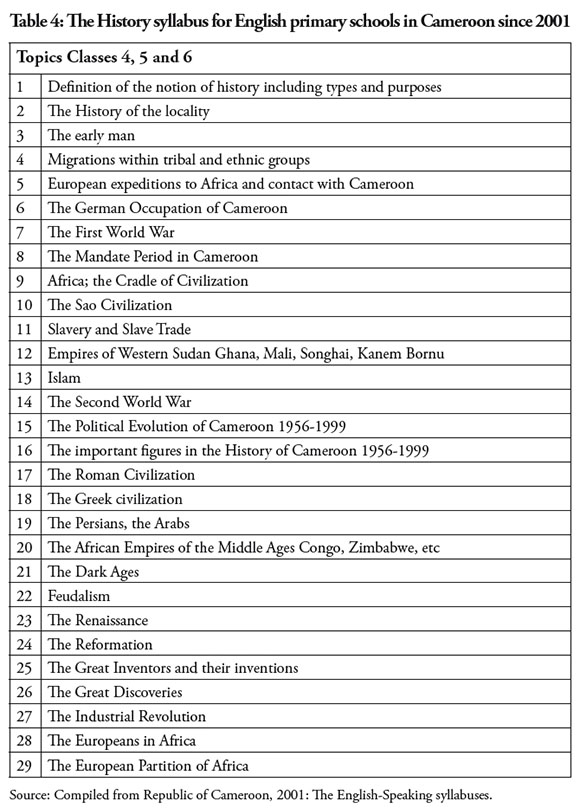

Law No. 98/004 of 14 April 1998 arising from the recommendations of the 1995 forum to Lay Down Guidelines for Education in Cameroon proclaimed in section 4 that the general purpose of education in Cameroon "shall be to train children who are firmly rooted in their culture.. .for their smooth integration into society ..." (Republic of Cameroon, 1998:n.p.). These goals were re-emphasised in objectives I, II, V and VIII ofa total ofnine objectives and in one way or another, relate to the teaching of national history. In respect to the law, the '"National Syllabus for English Speaking Primary Schools in Cameroon was published in 2001 (Republic of Cameroon, 2001). Although some Cameroon history topics were included in the new curriculum, a close look at the content of the history syllabus in this document shows a relative indifference to the cries of those who wanted the study of history in Cameroon schools to be dominated by local and national history. Of the 30 topics that feature in the three years of history teaching in elementary schools, nine are allocated to Cameroon history (Mostly repetitions of the same contents in the succeeding classes), less than six to the history of Africans in Africa and over fifteen to European history and European activities around the world. Comparatively what the English-speaking Cameroonian child studies in school about his/her own society vis-a-vis his French Cameroonian counterpart is not up to 05% of the entire Cameroon history on the syllabus.

It would be interesting to know what some European nations offer as elementary history content to ascertain whether it concerns itself so much about Africa as much as the Cameroon Educational system does about other continents. The German elementary school history syllabus published in two volumes (Connelson, 2000) contains a total of ten topics. These include; The American Revolution, the Industrial revolution, Imperialism, time line, German nationalism and the First World War, the Weimer Republic, Selected events ofthe Second World War, Germany and the World after 1945, and major events of the 20th Century. Even in topics dealing with issues out of Germany, the focus of the content is on the role of Germany in the events. According to Connelson's curriculum, apart from issues of imperialism, nothing else is mentioned or studied in the German elementary history class about Africa. The American Social Studies Curriculum is not entirely dissimilar to that of Germany in terms of emphasising national history (Hjelden, 2004).

The History curriculum of Anglophone secondary schools since 1961

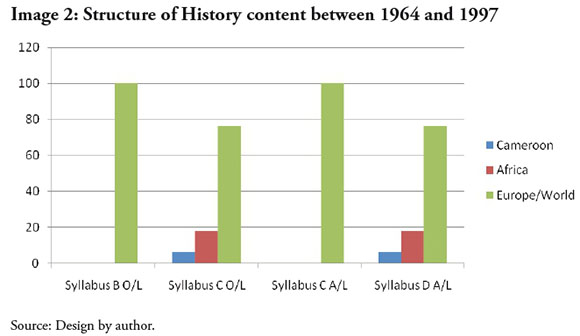

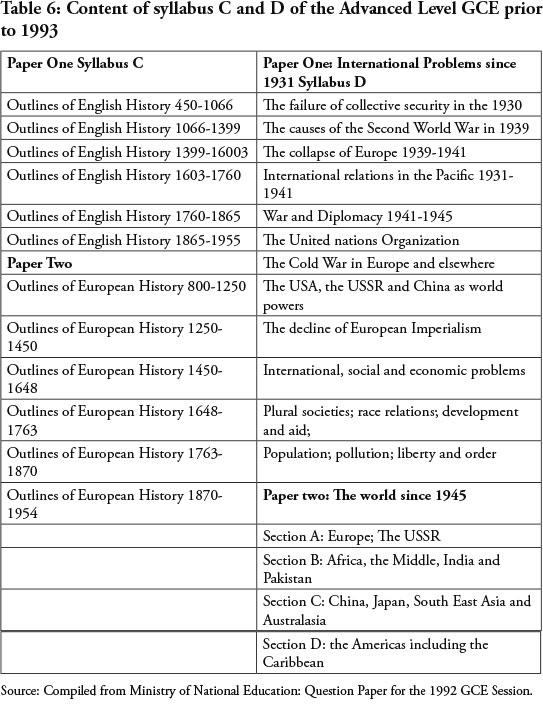

A close examination of the history content at the secondary school level in Cameroon demonstrates the same orientation to that obtained at the elementary level. Before 1993 when the Cameroon General Certificate of Education GCE Board was created, the GCE examination in syllabus B at the Ordinary Level and C at the Advanced Level was entirely on European History. Cameroon history was completely absent from that curriculum in those syllabuses (Ministry of Education, 1992). Of the more than 32 topics that constituted the tested curriculum of World Affairs Syllabus C at the GCE ordinary level and Syllabus D at the advanced level, only two questions represented the study of Cameroon history (Ministry of Education, 1992). This syllabus was broken down into the following sections; Africa and the Middle East, India and Pakistan, Europe and The USSR, China and Japan, USA, America and the Caribbean. The two questions on Cameroon history featured in the Africa and the Middle East section.

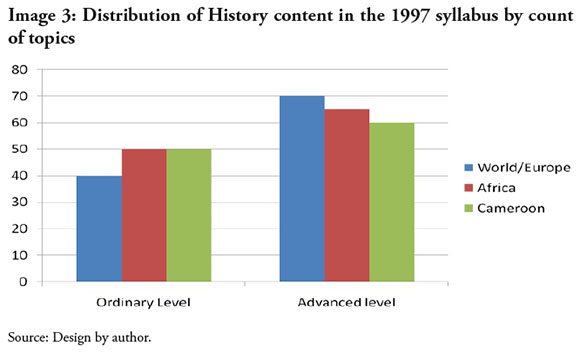

With the creation of the Cameroon GCE Board in 1993, the history programme of the senior secondary classes were redesigned to suit the new examination syllabus that the Board suggested. These programmes took effect in 1997. At both the Ordinary and Advanced levels, the two syllabuses mentioned above were abolished and a single curriculum was adopted. The new structure included Cameroon History since 1800, African History since 1800 and World History since 1848. This is what is in use today. Cameroon history carries 40% of the examination marks while Africa and World History carry 30% each. Despite this allocation, in terms of topics to be treated, world history still takes an undue toll on the teaching and learning of history (Cameroon GCE Board, 1997; Nteh, 2018). A manual count of the topics showed that the programme was still heavily loaded with World History.

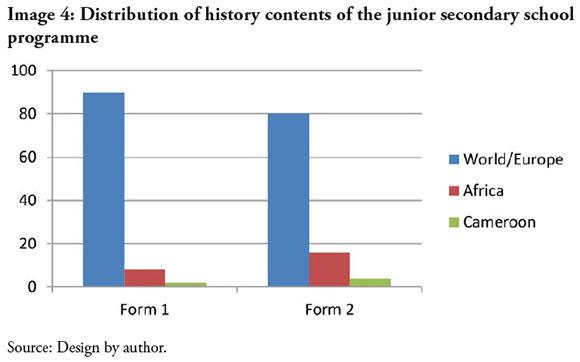

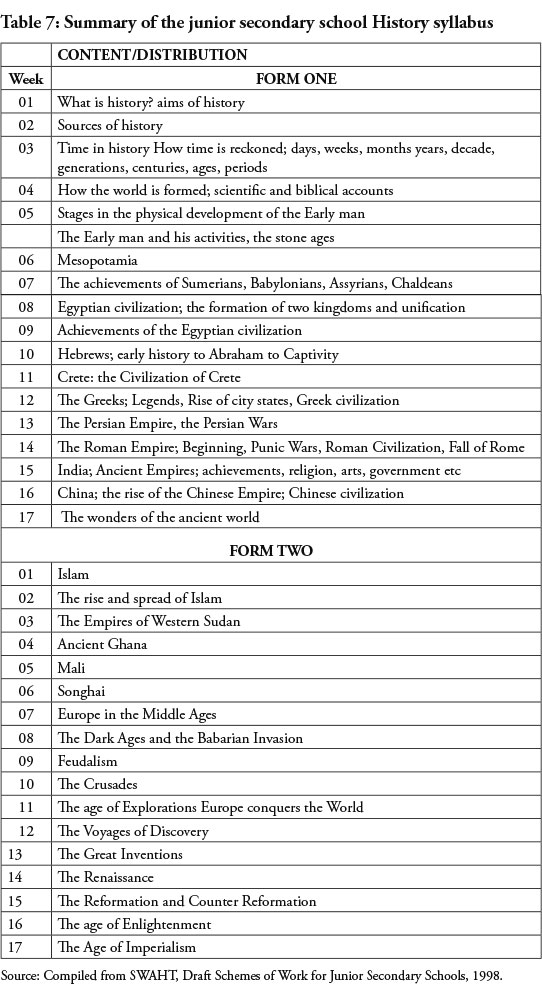

For the early secondary school classes, in Form One the first year of secondary schools in Cameroon, historical content includes, an introduction to history, history of ancient civilisations and nothing about Cameroon. In Form two the second year, emphasis is on Islam, African ancient empires and then moves on to the history of Europe in the Middle Ages, Ancient China and Japan and the Americas. Again, there is nothing about Cameroon (SWAHT, 1998). As from the third year, the orientation is towards the GCE and those who intend to take the subject at the GCE now begin studying the GCE syllabus presented above.

The History programme at the University of Buea

The University of Buea was established in 1993 as an answer to the cries of students of the Anglophone subsystem of education who were finding things relatively difficult in the then lone University of Yaoundé where instruction was predominantly in French (Ndongko &Nyamnjoh, 2000). Buea was therefore tagged the "Anglo-Saxon" University where instruction and the administrative structure were to follow the British university culture. It was therefore expected that the Department of History at Buea would be the nucleus of all the efforts of developing interest and focus on local history for the English subsystem of education at that level.

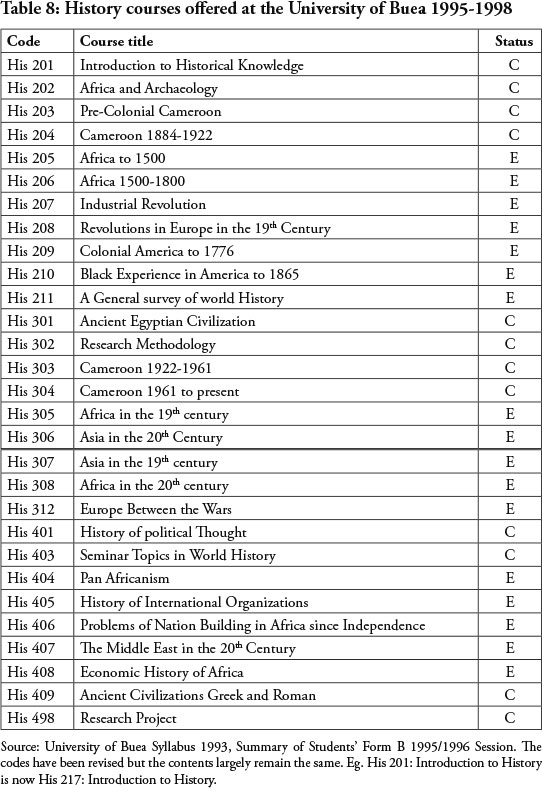

The Department had as its mission, "giving students a broad and firm grounding in Cameroon and African history (University of Buea, 1993). From a close look at the 1993 syllabus, one would observe that there was a determined effort to ensure that all students who registered in the department took courses in Cameroon history. The courses were structured into Precolonial Cameroon History, Cameroon under the German colonial administration, Cameroon under British and French Mandates and Trusteeships and Cameroon after independence (see Table 8 below). These courses were made compulsory for all undergraduate students in the Department. A very important innovation that the Department brought with the introduction of Cameroon history was the study of pre-colonial Cameroon which students had not been introduced to in the primary and secondary schools. Students therefore had to engage with the history of ethnic migrations, traditional administrations, local Cameroonian economies, cultures and societies before European contacts.

The third year course, His. 498: Research project was also intended to allow students undertake independent research on any aspects of Cameroon history of their choice but this was not to be limited to local or precolonial themes.

The His 498 Research Project gave the candidate a kind of specialisation but also a profound knowledge of that specific aspect of local history. Recent efforts 2015 also include the introduction of a Heritage studies Master's degree programme at the University of Buea (University of Buea, 2015) but the numbers enrolment are few and impact therefore minimal. A more robust effort is at the University of Bamenda, the second "Anglo-Saxon" university created in 2010 where a compulsory course on local History has been introduced at the undergraduate level (University of Bamenda, 2016). In terms of curriculum transformation in favour of local history therefore, the some progress has been made.

However, when one examines the extent to which the curriculum ensured that Cameroon history off-set the balance of historical studies at the university in respect for the national goal of curriculum indigenisation, the curriculum at Buea and Bamenda built in the majority by resource persons from Buea cannot be said to have fulfilled that objective. Compared to the four courses on Cameroon history, there were six courses exclusively on European history and four more on America and Asia. Although some of the courses were tagged "elective" the demands for the award of the Bachelor of Arts degree in History at Buea and Bamenda have made it such that at the end of the day graduates had less instruction in Cameroon history and more on European and World History. Between 1993 and 2007, a student had to accumulate ninety 90 credits to earn the Bachelors' degree in History. During this time, one course was valued at three credits.

In 2007, the university system in Cameroon adopted a harmonised degree certification system which affected course codes and credit values (University of Buea, 2009) but in terms of having more emphasis on local/Cameroon history, this reform has made no significant impact. At the undergraduate level, it is still the same four ours which have now taken on new codes and six credit values each. Their focus and contents area remain the same as in the pre-2007 years. Besides, these courses were designed for a general survey of the major political events of these periods. Apart from the local history course in Bamenda, the Heritage Studies programme at Buea and the Research projects undertaken at both institutions, highly essential specialised courses structured to deal with, economic, socio-cultural, religious and other critical thematic issues like human rights, gender, constitutional and legal issues, history of education etc. aimed at increasing the candidates' knowledge of the discipline at the local and national level and meeting the demands for an indigenous History curriculum in the country is yet available.

Challenges to curriculum transformation and way forward

The data above points to some efforts to make the History curriculum in Anglophone Cameroon more local contents based. It has however identified issues which make for a rational conclusion that at all levels of the Cameroon educational system, the indigenisation of the History curriculum has not been commensurate with the 1960 calls for the adaptation of school programs to local realities. One would expect that pupils and students of history who pass through the various levels of education in the Anglophone subsystem of education in the country would be well grounded in details of the cultural, social, economic and political history of the various localities in which they live or study in addition to that of the nation as part of their heritage. Rather, the study of World/European history and to a lesser extent other parts of pre-colonial and colonial Africa takes precedence over the inculcation of indigenous knowledge. What then have been the major challenges to curriculum transformation in the country?

One of the stumbling blocks to the introduction of a significant amount of local history rests on the fact that Cameroon is a country of over 260 ethnic groups with mutually unintelligible languages sitting about a kilometre apart in some areas (Neba, 1990). Because of this, even the curriculum experts who worked at the Institute for the Reform of Primary Education IPAR-Buea mentioned above raised the difficulty of deciding which of the local histories to include in the curriculum. As the experience with the use of local languages as the language of instruction had demonstrated, serious disagreements were bound to arise where one culture is represented in the curriculum against another for fear of hegemonic tendencies from those whose languages would have been selected (IPAR, 1977).

Linked to the above is the fact that most teachers have very limited knowledge of the local histories of the local communities they are posted to. This poses a problem of establishing local history contents to use for instruction. Unlike in some areas where training and recruitment of teachers especially at the elementary level is the prerogative of the local council or municipality, the system in Cameroon is centralised and teachers are posted to where a need is felt without minding their own cultural identity. In such places, it becomes difficult for the teachers to integrate into the local culture and work with children on local history projects.

There is also the problem of a completely examination oriented programme which leaves both some willing teachers and their pupils/students helpless as they have to adequately cover the syllabus to be tested. Although the nation adopted decentralisation in the 1996 constitution, its implementation within the educational system is slow and has not yet taken up curriculum reform as part of its agenda. The channels of flow for curriculum contents decisions is top-down; starting from the ministerial departments in Yaoundé to the regions. Those in the regions, divisions and subdivisions are only left with the implementation of hierarchy's decisions. By this top-down managerial approach to curriculum development teachers are left with no opportunities to contribute to change in terms of reform proposals to incorporate the history of the locality in their schemes of work.

A much more serious hindrance to curriculum reform is the political elite of the country. A majority of those called upon to design school programmes were people who received colonial education. Evidence of the initial curriculum reform of the 1960s demonstrate a semblance with the colonial curriculum implying that when the new elite were called upon to design the history programme soon after independence, they carefully replicated what they had acquired as historical knowledge and have since found it very difficult to move away from it. Ndlovu-Gatsheni laments that:

One of the strategies that have sustained the hegemony of the Euro-American-constructed world order has been its ability to make African intellectuals and academics socially located in Africa and on the oppressed side to think and speak epistemically and linguistically like the Euro-American intellectuals and academics on the dominant side (Ndlovu-Gatsheni 2013:5).

What then can lead to the establishment of a more local contents History curriculum in the Anglophone subsystem of education in Cameroon? First, policy makers in the country must realise that there is something wrong with the present system and make a sincere effort to decolonise/africanise the History curriculum. This realisation and subsequent action should lead to what Samir Amin termed delinking (Amin, 2006); cultural nationalism (Fanon, 1963); or a counter-discourse to cultural imperialism (Said, 1994). Generally, the authors point to the fact that is a necessary condition for the periphery to adopt new strategies and values that are different from those which have been prevalent under colonialism and neo-colonialism. Colonial domination had brought about "a veritable emaciation of the stock of national culture and the withering away of the reality of the nation" (Fanon, 1963:147). Curriculum indigenisation or Africanisation should be a significant vector in the struggle to regain that lost national identity and valour.

When questions of willingness are dealt with, the nation is expected to adopt a bottom-top approach to curriculum development in which teachers of this subject are expected to make proposals of issues within the localities which can feature in the curriculum. They should also be encouraged to undertake minimal research in the history of the communities in which they work, alongside their pupils/students. This would stimulate interest in local history among learners. Each community has lots of pages of unwritten history hidden in the memory of men and archives. Interest in the study of such contents begin by their documentation. This should start with teachers and their pupils.

Subject associations such as the South West Association for History Teachers, its counterpart in the North West Region are expected to play central roles in making curriculum proposals which should meet the demands of indigenous historical knowledge as well as review government proposals and make recommendations regarding best curriculum practices. Departments of History at the Universities of Buea and Bamenda are also expected to spearhead research and documentation of local history from which school contents can be made available. Regular workshops, refresher courses and education forums should also be organised. It is in such meetings that needs for curriculum revision often arise from discussions on the current situation, its strengths and weaknesses which may snowball into national reform efforts. A combination of these efforts would guarantee effectiveness in the curriculum indigenisation reform agenda in the country.

Conclusion

The examination of the transformation of the History curriculum in the three levels of education in the Anglophone subsystem of education in Cameroon has indicated that efforts have been undertaken at all the levels. However, these efforts are not significant to make for the conclusion that reform towards a predominantly local/national contents in history as indicated in policy documents since 1961 has been achieved. The situation could improve if the challenges identified are addressed and the recommendations implemented.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Prof Linda Chisholm (my PDRF Mentor), Prof Salim Vally (Director of the Centre for Education Rights and Transformation (CERT) Comrade Mudney Halim and Dr. Mondli Hlatshwayo for comments on the topic during my CERT seminar presentation on 11 September 2018. I also thank the peer reviewer(s) of the paper and editor of the journal for their review insights and consideration to publish the paper.

References

Ahidjo, A 1967. The political ideology of Amadou Ahidjo. Paris: l'Harmattan. [ Links ]

Aronowitz, S 1992. The politics of identity: Class, culture, social movements. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Awasom, N & Bojang, O 2009. Bifurcated world ofAfrican nationalist historiography. Lagos Historical Review, 9:1-26. [ Links ]

Awasum, S 2014. The challenging beginnings of a great educational project. In Sasse Chronicles 1939-2014: A Special Diamond Anniversary Publication of St Joseph"s College Sasse and Sasse Old Boys Association, pp. 17-19. [ Links ]

Ball, S 1983. Imperialism, social control and the colonial curriculum in Africa. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 15(3):237-263. [ Links ]

Bangura, A 2005. Ubuntugogy: An African educational paradigm that transcends pedagogy,andragogy, ergonagy and Heu tagogy. Journal of Third World Studies, 22(2):13-53. [ Links ]

Bude, U 1983. The adaptation concept in British colonial education. Comparative Education, 19(3):330-344. [ Links ]

Cameroon GCE Board, 1997. New syllabuses for the Cameroon General Certificate of Education Examination. Buea: Cameroon GCE Board. [ Links ]

Chisholm, L 2005. The making of South Africa's National Curriculum Statement. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 37(2):193-208. [ Links ]

Colonial Office, 1925. Memorandum of education policy in British Tropical Africa, London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. [ Links ]

Connelsen, D 2000. Spotlight on History: Material for German secondary and primary bilingual classes, Vol 1 and 2. Berlin: Cornelsen Verlag. [ Links ]

Department of Education (DoBE), 2018. Republic of South Africa, DoBE Report of the History Ministerial Task Team, February 2018. Pretoria: DoBE. [ Links ]

Diang, M 2013. Colonialism, neoliberalism, education and culture in Cameroon, Chicago: DePaul University College of Education Paper 52. [ Links ]

Elango, Z 2015. Anglo-French negotiations concerning Cameroon during the First World War 1914-1916: Occupation, condominium and partition. Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy andPerpectives, 9(2):109-128. [ Links ]

Fanon, F. 1963 The wretched of the earth, New York: Groove Press, Inc. [ Links ]

Federal Republic of Cameroon 1961. The constitution of the Federal Republic of Cameroon. Yaounde: Imprimerie Nationale. [ Links ]

Fonkeng, G 2007. The history of education in Cameroon, 1844-2004. Lewiston, NY: The Edwin Mellen Press, Ltd. [ Links ]

Freund, B 1984. The making of contemporary Africa. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University. [ Links ]

Goodreads (a social cataloging application), 2018. An analysis of HG Wells and other colonial History textbooks in the context of geographical determinism. Available at http://.www.goodreads.cm/hg-wells. Accessed on 10 November 2018. [ Links ]

Grosfoguel, R 2011. "Decolonizing post-colonial studies an paradigms of political-economy: Transmodernity, decolonial thinking, and global coloniality". Transmodernity: Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production of the Luso-Hispanic World 1(1):1-19. [ Links ]

Gwei, S 1975. Education in Cameroon: Western pre-colonial and colonial antecedents and the development of higher education. Unpublished PhD thesis. Chicago: University of Michigan. [ Links ]

Hjelden, E 2004. Personal interview (Social studies student teacher on internship at Baptist High School Buea between September and December 2004 from the University of Minnesota) Roland Ndille (Researcher), 3 December 2004. [ Links ]

IPAR, Buea 1977. Institute for the Reform of Primary Education: Report on the Reform of Primary Education. National Archives Buea, NAB. [ Links ]

Jesse-Jones, T 1925. Education in Africa: A study of west, south and equatorial Africa by the African Education Commission under the auspices of the Phelps-Stokes fund and the Foreign Missions Society of North America and Europe. New York: Phelps-Stokes. [ Links ]

Kwabena, O 2006. The British and curriculum development in West Africa: A historical discourse. Review of Education, 52:409-423. [ Links ]

London, N 2002. Curriculum and pedagogy in the development of colonial imagination: A case study. Pedagogy, Culture and Society, 10 (1): 95-121. [ Links ]

MacOjong, T 2008. Philosophical and historical foundations of education in Cameroon 18841960. Limbe: Design House. [ Links ]

Marmer, E & Sow, P 2013. African History teaching in contemporary German textbooks: From biased knowledge to duty of remembrance. Yesterday&Today, 10:49-76. [ Links ]

Marsden, W 2013. The school textbook: Geography, History and Social Studies. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Ministry of National Education (MINEDUC) 1992. General Certificate of Education Examination Papers for History at the Ordinary and Advanced Levels various syllabuses for 1992 session. [ Links ]

Myers, C & Myers L 1990. An introduction to teaching and schools. Fort Worth, TX: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. [ Links ]

National Archives Buea-Cameroon (NAB) 1923. File Sb/a/1923, Education reports southern provinces, 1923 and 1924. Inspection report on primary education for Mamfe and Kumba division, other correspondences: [ Links ]

NAB, 1927. File Sb/a/1927/2 Education correspondence. [ Links ]

NAB, 1933. File Sb/a/1933/1 Annual Report, Education Department, Southern Cameroons. [ Links ]

NAB, 1933. File Sb/a/1933/19 CM7 Vol.1, Education annual and League of Nations Reports. [ Links ]

NAB, 1934. File Sb/a/1934/2 Schemes of work and time tables, 1932-1934, Cameroons Province, NAB. [ Links ]

NAB 1979. File Sb/d/1979/11, School vacation courses: Reports by the Coordinator. South West Provincial Delegation. [ Links ]

NAB, 1980. File Sb/a/cm218, Schemes of work and time tables, 1980, Daily record of work books at GPS Kumba Town for Class five, six and seven for 1987/1988 at Government Practicing School Kumba Town. [ Links ]

NAB, 1958 File sb/g/1958/1, Examinations: London Matriculation, 1957-8. [ Links ]

Ndille, R 2014. Britain and education in the development of Southern Cameroons: A Critical historiographical analysis, 1916-1961. Unpublished D.Litt et Phil Thesis, Pretoria: University of South Africa. [ Links ]

Ndille, R 2015. From adaptation to ruralisation of education in Cameroon: Replacing six with half a dozen. African Educational Research Journal, 3(3):153-160. [ Links ]

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S 2013. The entrapment of Africa within the global colonial matrices of power: Eurocentrism, coloniality, and the deimperialization in the twenty-first century. Journal of Developing Societies, 29(4):334-349. [ Links ]

Ndongko, T & Tambo L(eds.) 2000. Educational development in Cameroon 1961-1999. Platteville: Nkemnji Global Tech. [ Links ]

Neba, A 1990. Modern Geography of the Republic of Cameroon, 3rd edtion. Bamenda: Neba Publishers. [ Links ]

Nfi, J 2014. Nigerians on mission in the British Southern Cameroons, Bamenda: Baron Printing House. [ Links ]

Ngoh, V 2011. The untold story of Cameroon reunification 1955-1961. Limbe: Presprint Plc. [ Links ]

Nteh, R 2018. Personal interview (History Teacher and Executive member of the Kupe-Manenguba Divisional Branch of the South West Association of History Teachers) Roland Ndille (Researcher), 28 January. [ Links ]

Presbyterian Central Archives and Library Buea-Cameroon (PCCCAL) 1975. File 236, School record books and diaries. [ Links ]

PCCCAL, 1966. File 864 PCCAI; History Syllabus. [ Links ]

PCCCAL, 1967. File 8142. Matters regarding syllabuses, notes, schemes of work and textbooks 1962-67. [ Links ]

Peters, R 1966. Ethics in education. London: George Allen and Unwin [ Links ]

Popkewitz, T (ed.) 2000. Educational knowledge: Changing relationships between the state, civil society, and the educational community. Albany, N.Y: State University of New York Press. [ Links ]

Radio, 702 2018. New History curriculum in South Africa to be more Afrocentric. Podcast on of 22 May 2018 10:51 am. Available at www.702.co.za. Accessed on 31 October 2018. [ Links ]

Ramoupi, N 2012. Deconstructing Eurocentric education: A comparative study of teaching African-centred curriculum at the University of Cape Town and the University of Ghana-Legon. Postable, 7(2):1-17; [ Links ]

Republic of Cameroon, 1963. Law No. 63/DF/13 of 19 June 1963 on the harmonization of educational structures in the Federal Republic of Cameroon. Yaoundé: Presidency of the Republic. [ Links ]

Republic of Cameroon, 1998. Law No. 98/004 of 14 April 1998 to law down guidelines for education in Cameroon. Yaoundé: Imprimerie Nationale [ Links ]

Republic of Cameroon, 2001. The New English syllabus for Anglophone primary schools in Cameroons. Yaoundé: Ministry of National Education. [ Links ]

Rodney, W 1982. How Europe underdeveloped Africa. Washington: Howard University Press. [ Links ]

Schofield, H 1978. The philosophy of education: An Introduction. London: George Allen and Unwin. [ Links ]

Southern Nigeria, 1930. Provisional school syllabus for Southern Cameroons, Vol 1 and 2. Lagos: Christian Mission Society Bookshop. [ Links ]

SWAHT, 1998. South West Association of History Teachers. Schemes of work for History for Junior secondary schools Forms 1 & 2. Buea: Teachers Resource Centre. [ Links ]

Tambo, L 2000. Strategic concerns in curriculum development in Cameroon. In: T Ndongko & L.Tambo. Educational Development in Cameroon 1961-1999. Platville, MD: Nkemnji Global Tech. [ Links ]

Tambo, L 2003. Cameroon nationaleducationpPolicy since the 1995forum. Limbe: Design House. [ Links ]

The Conversation Newspaper, 2018. Western Civilization? History teaching has moved on, and so should those who champion it. Available at https://theconversation.com/western-civilisation on 31-10-2018. Accessed at 6 June 2018. [ Links ]

Tosam, J 1988. Implementing educational change in Cameroon: Two case studies in primary education. Unpublished PhD Thesis. London: University of London. [ Links ]

UNESCO, 1985. The Educational process and the historiography in Africa. Paris: UNESCO. [ Links ]

University of Bamenda, 2016. Draft syllabuses of the Department of History of the University of Buea submitted to the Ministerial Commission for the Harmonization of University Programmes. Yaoundé: Ministry of Higher Education. [ Links ]

University of Buea, 1993. Syllabuses of the University: Limbe: Presprint. (2003 and 2009 editions also consulted). [ Links ]

University of Buea, 2015. Draft programme proposal for the professional Master programme in Heritage Studies at the Department of History submitted to the Academic Planning Committee. [ Links ]

Webster, A 2006. The debate on the rise of British Imperialism. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [ Links ]

Wells, H 1920. The outline history of the world: Being a plain history of life and mankind. London: George Newnes. [ Links ]

West Cameroon, 1963. Education policy of the Federated State of West Cameroon. Buea: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Whitehead, C 2005. The historiography ofBritish imperial education policy, Part II: Africa and the colonial empire. History ofEducation: Journal of the History ofEducation Society, 34(4):441-454. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00467600500138147. Accessed on 20 August 2108. [ Links ]

Whitehead, J 2008. Using a living theory methodology in improving practice and generating educational knowledge in living theories. Department of Education, University of Bath: Bath, UK. Available at edsajaw@bath.ac.uk. http://www.actionresearch.net. Accessed on 12 November 2011. [ Links ]