Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Yesterday and Today

On-line version ISSN 2309-9003

Print version ISSN 2223-0386

Y&T n.20 Vanderbijlpark 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2223-0386/2018/n19a3

ARTICLES

The dialectics of historical empathy as a reflection of historical thinking in South African classrooms

Daniel RamorokaI; Alta EngelbrechtII

IFaculty of Education, Humanities Education University of Pretoria. Ramoroka.d@dbe.gov.za

IIFaculty of Education, Humanities Education University of Pretoria. Alta.Engelbrecht@up.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The research explores the understanding of the concept Historical empathy as conceptualised by the two teachers sampled in this study. The article analyses the pedagogical practices of two Grade 12 History teachers who used the theme of the Vietnam War of 1954 to 1975, also known as the Second Indochina War, and in Vietnam as the Resistance War Against America or simply the American War, was a conflict that occurred in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. This is one of the new themes included in the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) to cultivate tenets of Historical empathy in their classrooms. The research utilises a qualitative research paradigm to enable the researchers to interview teachers at their schools and observe them interacting with the phenomenon being investigated in their natural environment in the classrooms. The article uses the dual theoretical framework designed by Barton and Levstik (2004) which embodies both elements of affective and cognitive domains to evaluate the perspectives of two teachers and their pedagogical practices in the classroom. According to the findings, both teachers used suitable and relevantprimary and secondary sources during the lesson presentations. Teachers demonstrated characteristics of emotional and cognitive empathy during the interviews and these divergent elements were displayed during the teaching of the Vietnam War. Quite often learners were encouraged by one teacher to sympathise and align with the victims of the war which is caused by their past agony and psychological trauma resulting from the experiences of their communities during the apartheid government and this demonstrated shared normalcy. The second teacher empathised with the Vietnamese soldiers and saw them as gallant soldiers against the strong US troops rather than as victims thereby displaying some elements of cognitive Historical empathy.

Keywords: Historical empathy; Presentism; Historical contextualisation; Normalcy; Sense of otherness; Multi-perspectivity

Introduction

Historical empathy is a critical historical thinking skill that has the potential to enhance democracy in South Africa by promoting reconciliation, nation building, tolerance and appreciation of the diverse cultures and histories of the different South African communities. It has the capacity to encourage a healthy scepticism and a reasoned ethical judgement which will promote critical thinking in the History classroom (Seixas & Morton, 2013). Historical empathy may be seen as a valuable skill for helping learners understand the actions of people, and events prior to their own. Placing Historical empathy within a proper framework will ensure that teachers understand its tenets and potential for increasing historical thinking skills within the classroom (Cunningham, 2009, Harris, 2016:169). The post-1994 or post-apartheid South Africa is characterised by debate led by "fall movements" which question the value of the 1994 political settlement including new Constitution and Truth and Reconciliation. Currently South Africa is grappling with controversial issues that are causing tensions such as racism, land ownership, access to higher education and destruction of historical statues and Historical empathy can bring about tolerance of paradoxical views held by South Africans. This point is emphasised by the South African democratic Teachers Union's secretary-general, Mugwena Maluleke, a member of the History task group that recommended that History be made compulsory and asserts that "with History being compulsory we can teach our learners empathetic skills which help this angry country to learn how to understand others' viewpoints without resorting to violence" (Mbude, 2018).

The article explores the teachers' understanding of Historical empathy and how they develop it in the classroom. The purpose of their teaching was to develop Historical empathy through engagement in the cognitive analysis of historical evidence and to ultimately achieve what Seixas (2013) termed a reasoned ethical judgement, supported by valid evidence. This judgement, for Seixas (2013), constitutes the cognitive domain within the framework of Historical empathy represented by cognitive elements such as otherness, historical contextualisation and different perspectives. These three elements that are perceived to be the most challenging tenets of Historical empathy, will be assessed along with the emotive elements embodied in the dual framework of Historical empathy designed by Barton and Levstik (2004). The article further highlights congruency between the conception of Historical empathy and how its elements were cultivated in the classroom by the two teachers. Finally, the article assesses the role of historical evidence selected by the teachers in determining which elements of the dual model of Historical empathy are emphasised in the two classrooms.

Research problem

Historical empathy has been a difficult skill to cultivate in the classrooms and some countries became skeptical about teaching it to its learners due to the need to empathise with historical actors including their enemies who held an opposing view. For example, some Americans were skeptical about the requirements of learners to empathise with historical actors in Cuba (Davis,Yeager & Foster, 2001). In the past, textbooks in South Africa were based on one historical perspective, the Afrikaner nationalist perspective. History teaching did not promote historical thinking and empathy. The content was structured to indoctrinate the South Africans about the invincibility of the white man and inferiority of the black people. With the introduction of the National Curriculum Statement in 2008, the apartheid content was removed from prescribed textbooks and replaced mostly by a more balanced and decolonised perspective (Kallaway, 1993). This led to many Afrikaans medium schools doing away with History (Black, 2014). The study of History was also affected by the introduction of Life Orientation which was made a compulsory subject. However, there has been a vigorous discourse on the appropriateness of Life Orientation in making learners true South Africans and Africans and this led to a debate on making History compulsory. The Minister of Basic Education, Angie Motshekga appointed a task team in 2015 to look into the issue of making History compulsory and the task team recommended that History be made compulsory and should replace Life Orientation in Grade 10 to Grade 12. If History becomes compulsory in South Africa, the Department of Basic Education will emulate 13 African countries where History is a compulsory subject (Mbude, 2018).

With the euphoria injected by the news of History being made compulsory, the obstacle remains the teaching methodology. The teaching methodology is still confined within a paradigm of the transmission model of teaching. The focus is more on teaching factual knowledge rather than the conceptual and procedural knowledge. This type of an approach is driven by the need to prepare the learners for the Grade 12 examination rather capacitating them to engage in the elements of Historical empathy.

This outdated model of teaching has the propensity to undermine the teaching of Historical empathy, a skill that can defuse the violent culture of South African society (Ramoroka, 2016:18). If learners are immersed into the culture of other South African communities which differ from them in terms of race, gender and class, they are likely to tolerate them and appreciate the differences.

With the introduction of the new curriculum in 2008, the teaching methodology did not change much. Even with a refined CAPS curriculum which embodied elements ofHistorical empathy, the teaching methodology still remains an impediment (Seixas & Morton, 2013). It is difficult to decompose Taylor's curriculum framework in order to make way for Vygotsky's social and cultural constructivist framework which advocates historical knowledge construction process in the classroom. A method based on dialogical and dialectical methods and which is appropriate for the cultivation of Historical empathy (Vygotsky, 1978; Ramoroka, 2016:18).

The use of textbooks as a metanarrative is also an impediment in the teaching of historical thinking. Although textbooks contain secondary and primary sources, which are mostly poorly contextualised, teachers continue to rely on the textbook narrative constructed by historians. This serves as an obstruction in the teaching of Historical empathy. Teachers need to explore other sources outside the textbooks (Ramoroka & Engelbrecht, 2015). Some teachers seldom go beyond the sources provided by the textbooks. In the case of the Vietnam War, there are plenty of valuable primary sources that exist on the internet that were not explored by the teachers which have the capacity to teach Historical empathy (Harris, 2015; Ramoroka & Engelbrecht, 2015).

Research Methodology

The question driving this research is as follows: To what extent can the concept ofHistorical empathy be utilised to engage learners in historical thinking in the classroom? In order to respond to the question driving this research, a qualitative research interpretivist paradigm has been used. Qualitative design presupposes that meaning is constructed through the interaction between humans, and therefore meaning does not exist independent of the human interpretive process. The data-collection methods employed include open-ended interviews and lesson observations. During the interviews, teachers were allowed to use any historical theme and current events to demonstrate their understanding and epistemological beliefs about critical thinking and Historical empathy in the study of History. The interviews and lesson observations were conducted at the two schools. The lessons were planned for 45 minutes. However, in some cases the time was extended to 90 minutes because of the presence of the researchers in the classroom. The research uses a thematic approach in the analysis of data which is underpinned by a process of encoding qualitative information (Boyatzis, 1998). Two teachers from two seperate urban schools in the Gauteng province of South Africa have been sampled for this research and both were interviewed on conceptions of Historical empathy and how it can be taught in the classroom. These teachers were subsequently observed in the classrooms, teaching historical empathy using Vietnam as the main theme.

For compliance with ethical standards, pseudonyms are used for the two teachers and the names of schools and districts are not mentioned. In addition, letters of consent were signed by the teachers and principals of the two schools and the research was approved by the Head of Department in the Gauteng Department of Education.

The Vietnam War of 1954 to 1975, also known as the Second Indochina War, and in Vietnam as the Resistance War Against America or simply the American War, refer to the conflict that occurred in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975 (Spector, 2018). The Vietnam War has been selected as a theme that is appropriate for understanding the challenges experienced by teachers when teaching Historical empathy in the classroom. The war was highly photographed and accounts of the war by photographers, soldiers and ordinary people are extensive and therefore there is ample opportunity for learners and teachers to engage with multiple and conflicting pieces of historical evidence. Some of the sources used by the two participating teachers included photographs of aerial bombardment by the USA and booby and punji traps used by Vietnamese soldiers. A documentary video was used by one teacher, showing the live battle during the war and interviews with soldiers who participated in the Vietnam War.

The start of the Vietnam War was a subject of intense contestation by historians, a phenomenon which was not unique to the Vietnam War. The multiple entries by the US into Vietnam complicate the issue of the start of the Vietnam War. Some North Vietnamese view the war as a colonial war against the US and the continuation of the first Indonesian war against France. The South Vietnamese saw it as a civil war and a battle to defend their country from being taken over by communism. The US saw the war as part of the domino theory and as a strategy to contain the spread of communism. Primarily, every American president regarded the enemy in Vietnam -the Vietminh; its 1960's successor, the National Liberation Front (NLF); and the government of North Vietnam, led by Ho Chi Minh - as agents of global communism (Rotter, 999:1).These divergent views have led to Carland to assert that: to ask when the Vietnam War started for the United States is, metaphorically speaking, to open a can of worms. Before 1950, it was clear that the United States was not engaged in the war in any serious way. After 28 July 1965, it became equally clear that the United States had indeed become engaged in the war (Carland, 2012:1). The strong argument advanced by Carland (2012:3) is that by sending helicopters, pilots, and maintenance personnel to Vietnam and allowing the helicopters to support South Vietnamese combat operations (for example, ferrying troops to the field and providing fire support as well as training the South Vietnamese for operations), President Kennedy had initiated the process through which the United States assumed a combat role. If pushed to select a date with some traction, one might choose December 1961 or July 1965 (Carland, 2012:3).

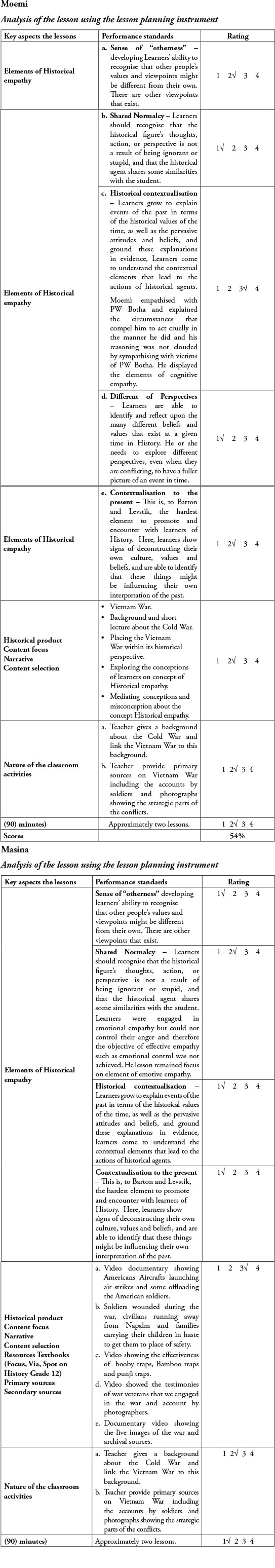

A research instrument has been developed by the researchers and was used to analyse data collected during the interviews and in classrooms relating to the teaching of Historical empathy using the theme of Vietnam War. The purpose of this instrument is to assess elements of emotive and cognitive domains embedded in the dual model of historical thinking developed by Barton and Levstik such as sense of "otherness", shared normalcy, historical contextualisation, different perspectives and contextualisation to the present. The instrument is intended to assist the researchers to ascertain elements that were demonstrated by the teachers during the teaching of Historical empathy. Teachers in this instrument were expected to juxtapose elements of Historical empathy with background information and primary or secondary sources relating to the theme. The instrument is also designed to assess classroom activities which included the use of historical evidence embedded in primary and secondary sources. Each criterion was evaluated based on a four-point scale, (1 poor, 2 limited, 3 moderate and 4 powerful) evaluating the display of elements of Historical empathy.

Conceptual framework

Historical empathy is often thought of as vicariously walking in someone else's shoes in order to interpret how that person feels about things, and to understand why they might have travelled down one road and not another (Davidson, 2012). Empathy is a person's ability to comprehend the other's position, even though he does not have the direct experience to do so. In other words, empathy is one's ability to put oneself in another person's shoes even if the other is a stranger to him or even if he thinks differently than himself. It is the ability to participate in the psychological experiences of another person as if he were reliving them himself (Lazarakou, 2008).

Historical empathy has been a subject of intense contestation over many decades and curriculum experts have viewed it as a difficult historical thinking concept to cultivate. The discourse reached its polemical edge in the 1990s due to divergent views on what constitutes Historical empathy and whether sympathy or emotive empathy is an exponent of Historical empathy or its detractor. Experts developed different theoretical frameworks not only to facilitate the cultivation of elements of Historical empathy in the classroom but also to advance their affective - cognitive paradigms over the equation of Historical empathy. A number of studies have shown that some teachers know nothing about Historical empathy while others only understand the emotional aspects of it (Barton & Levstik, 2004; Jenkins, 1991). Some from the post-modernist perspective have gone to the extent of rejecting the concept and claimed that it is impossible to achieve (Jenkins, 1991). In the end some agreed that learners can never fully empathise with the victims of the Holocaust or Vietnam War (Borton & Levstik, 2004; Margery, 2017:23; Jenkins, 1991). Tensions emerged between proponents of the cognitive domain and the proponents of the dual process of Historical empathy. Some consider emotional empathy as an impediment to developing empathy while others view emotive empathy or sympathy as enabling knowledge in order to enable learners to develop cognitive elements of empathy. Both groups of experts agree that ultimately the learners should be able to demonstrate the cognitive elements of Historical empathy as part of historical thinking (Borton & Levstik, 2004; Margery, 2017).

Barton and Levstik (2004) express the view that Historical empathy is a dual process which embodies both the cognitive and emotive domains and these elements need to be considered to ensure that learners are able to control their emotions on their journey towards developing the concept of Historical empathy. Barton and Levstik (2004) resolved to design an all-encompassing model of Historical empathy by identifying five elements of Historical empathy (or perspective recognition), namely an appreciation for a sense of otherness of historical actors, the shared normalcy of the past, the effects of historical context, the multiplicity of historical perspectives, and the application of these elements to the context of the present.

This article adopts the dual process of Historical empathy as a conceptual framework, designed by Barton and Levstik, (cited in Margery, 2017). This framework is the most cited in the literature (Margery, 2017:23; Davidson, 2012; Harris, 2016). This framework has already been tested empirically by doctoral students who have researched Historical empathy and demonstrated the potential of this model to inculcate central tenets of Historical empathy (Margery, 2017 & Harris, 2016). The framework comprises five elements (Barton & Levstik, 2004; Margery, 2017:23), namely, Sense of "otherness", Shared normalcy, Historical contextualisation Different perspectives and Contextualisation to the present.

Literature Review

Demonstrating the display of empathy

Four studies are analysed in this section, two are international studies and two are part of South African literature.

The first study is a doctoral thesis written by Dillenburg Margery in 2017 at Boston University. Margery (2017) in a study entitled "Understanding Historical empathy in the classroom", explores understanding of Historical empathy by teachers and elucidates how students' response to the pedagogical activities interfaced with tenets of Historical empathy. Margery (2017) uses cognitive and effective theoretical model developed by Barton and Levstik (2004) in an attempt to assess the understanding of Historical empathy. He used one History classroom to observe the teaching of elements of Historical empathy and interviewed 13 learners in the first semester and four in the second semester. Margery (2017) immersed himself into the current debate on the definition of empathy and attempted to disentangle the intricacies that entangled the teaching of the concept Historical empathy. The focus the lesson was the holocaust especially the activities of Hitler and the Nazi party in Germany. In his study it was found that learners demonstrated a condescending sense of "otherness" which decreased overtime. Initially students just saw Hitler as a crazy and racist leader and later the students began to see the other side of Hitler and characterised him as a charismatic leader and according to Margery (2017:22) the learners were beginning to create a boundary between themselves and the Holocaust which was a demonstration of progress in attaining a sense of "otherness". A "shared normalcy" was experienced by learners who experienced hardship under apartheid and compared their experiences with that of the Jews during the Holocaust (Margery 2017:22). However, the evidence presented on the effectiveness of the dual-process model in enhancing Historical empathy is very limited and the study failed to provide adequate evidence to the effect that emotive empathy is a stepping stone towards cognitive empathy. The study fell short of demonstrating the elements of historical contextualisation which is central to understanding Historical empathy.

The second study is also a doctoral thesis written by Billy Kenneth Harris in 2016 at Walden University in the United States of America. In a study entitled "Teacher strategies for developing Historical empathy" (Harris, 2016:6). He explores high school teachers' perspectives on using Historical empathy in their teaching. He sampled two schools and included seven teachers in the study. Teachers were observed teaching empathy, reflecting the theoretical framework developed by Barton and Levstik (2004) which embodies the elements of cognitive and affective domains. The focus was to ensure that teachers understand the difference between sympathy and empathy and to use empathy in order to understand the context as part of historical understanding. According to the findings of the study, teachers demonstrated few elements of Historical empathy and contextualisation and multiple perspective were the most difficult to demonstrate. What is significant about the study is Harris's cautionary remark that teachers should monitor too much emotion provoked in the classroom because it can return learners to presentism and enrage them and they are then likely to remain within the affective domain rather than moving towards the cognitive domain. However, the study also failed to demonstrate emotional empathy as logical step towards attaining cognitive elements of Historical empathy. Instead emotive elements appeared to be the precursor of presentism, an obstacle in the way of attaining Historical empathy.

The third study was carried out by Sarah Dryden (1999), a doctoral graduate from the University of Cape Town, in the thesis entitled "Mirror of a Nation in Transition". She explores the difficulty experienced by History teachers in South Africa when the History content and approach was changed from apartheid content (which excluded African History) to content that included black people. She explored four schools representing different communities and sometimes a mixture of these communities where History was a subject of contestations between different communities represented by learners. According to Dryden (1999) some teachers used Historical empathy in order to foster unity amongst black and white. Mr Weir, one of the History teachers, tried to put his learners into Hector Pieterson's shoes, to show them what their own reactions would be if they found themselves in his situation in the Soweto school. One of the shortcomings of this study there was no evidence of engaging learners in elements of both emotive and cognitive empathy in the classroom.

The fourth study is an article by Ramoroka and Engelbrecht (2015) entitled The role of History textbooks in promoting historical thinking. In this article the authors analyse three textbooks that are utilised by teachers in South Africa and the analysis is focused on the theme Vietnam War to assess the appropriateness of sources to teach Historical empathy. The following textbooks were analysed, namely Via Africa History (Grade 12 (Grove, Manenzhe, Proctor, Vale & Weldon, 2013) and Focus History Grade 12 (Fernandez, Wills, McMahon, Pienaar, Seleti & Jacobs, 2013), Spot On History Grade 12 (Dugmore, Friedman, Minter & Nicol, 2013). The study uses the cognitive analyses designed by Wineburg (2001) as a theoretical framework. It was found that all the primary sources contained in the books were not fully contextualised. The study found among others, that all three textbooks do not reflect all the characteristics of sourcing such as the name of the producer of the source and the date in which the source was produced and published. The absence of this information makes it difficult for learners to contextualise sources by making sense of the differences between documents. The study succeeded in identifying sourcing heuristics as an impediment to the cultivation of historical contextualisation which is critical in the inculcation of the cognitive elements of Historical empathy. The shortcoming of this research is that is it did not provide adequate evidence on both aspects of the dual process of Historical empathy which embodies both emotive and cognitive domains.

The four studies provided some insight on how Historical empathy can be displayed in the classroom. The first and second studies are doctoral studies achieved in 2016 and 2017 at international universities. These studies explore the understanding of Historical empathy by teachers and the demonstration of its tenets by learners in the classrooms. However, the two studies fail to provide convincing evidence on the display of cognitive elements of Historical empathy. The third study was based on the South African context and the study fell short of demonstrating elements of both emotive and cognitive domains. Finally, the fourth study explores three prescribed textbooks with special focus on primary sources relating to the Vietnam War. The study revealed deficiencies in the citing of sources which makes it difficult to contextualise them and historical contextualisation is critical in the teaching of Historical empathy.

Findings: Teachers' conceptions of Historical empathy as historical thinking

Teachers' conceptions of Historical empathy

For teachers and learners to be able to display Historical empathy they need to situate the historical events in time and place in order to avoid using the presentism standards to judge the people of the past. In exploring the conceptions of teachers, the two teachers were asked about the meaning of Historical empathy and its importance. The following responses were observed. According to Masina, one of the research participants, "Historical empathy has to do with the feelings of the people of the past and it is an important historical skill. It is putting you[rself] in the shoes of the people of the past". In respect of the conceptual framework this assertion addresses the affective domain and learners putting themselves in the shoes of Steve Biko are likely to acquire a sense of Shared Normalcy which is displayed when learners share almost similar experiences with historical character. Masina did not explain the meaning of "putting yourself in the shoes of the people of the past" and the example that he used locates his conception within the emotive domain of Historical empathy. He did not attempt to locate the Steve Biko's dead in detention within the broader context of apartheid regime and its reaction against political activists. Why are learners not asked to empathise with those who ill-treated Steve Biko or to explore the circumstances that compel them to take action against Steve Biko? The absence of evidence to respond to this question in Masina's testimony clearly shows that he was more concerned about the victims of apartheid violence.

Masina wanted learners to empathise with Steve Biko and indicate how he had felt when he was ill-treated in prison. Of course learners would sympathise with him because he was part of the struggle against apartheid, but according to Jenkins (1991) learners will never be able to feel like Steve Biko. To Foster (2001), empathy does not include emotional involvement with people of the past. In fact, all emotional involvement undermines Historical empathy, and should be considered sympathy. As the proponent of the cognitive aspect of Historical empathy, in terms of Foster's theoretical framework, Masina was far from articulating empathy. However, in respect of the dual process of empathy, sympathy is considered by Blake as a stepping stone towards attaining empathy. For this reason, Masina felt that learners can experience a shared normalcy - by recognising that the historical agent shares some similarities with them such as human pain that can be accessed if one shares similar experiences with Steve Biko. In terms of Historical empathy, involvement of the learners in sympathy or emotive empathy is inadequate and Masina is required to demonstrate aspects of cognitive empathy such as "otherness" and contextualised thinking and different perspectives, which are the three elements that are at the heart of Historical empathy. He needs to explain the circumstances that compelled the authorities at the time to kill Steve Biko and this should include the type of leadership at the time and the reasons the leadership intensified war against political activists. He also needs to demonstrate a balanced perspective between the victim and perpetrators. However, he perceives empathy as a skill that requires learners to empathise with the victims. Similar to the three studies (Harris, 2016; Margery, 2017, Dryden, 1999) the aspects of sympathy and emotive empathy appear to be associated with empathising with the victims. The studies failed to provide evidence of empathising with perpetrators such as Hitler in case of the Holocaust and the USA in the case of the Vietnam War.

Moemi, another research participant, asserts that:

I can be wrong but I equate empathy with sentiment where people can empathise with certain events because they relate somehow with those events.

In respect of the dual process of Historical empathy, this assertion is located within the emotional domain. However, as Moemi further explained by providing examples, other elements of the cognitive domains were addressed. In order to explain the concept further, Moemi describes South African historical events in the 1980s under PW Botha, the president of apartheid South Africa, known as die Groot Krokodil (Big Crocodile). PW Botha, according to Moemi, designed the "total strategy" in order to destroy all communists' protests in the townships, which were accordingly classified as communist activities in the 1980s. According to Moemi, "it was during his regime that many of the youth were killed and some went into exile to join the liberation forces". He was also "the president who started negotiations with Mandela while he was in prison". In presenting this background and balanced evidence of events during PW Botha's era, Moemi addresses some elements of Historical contextualisation which requires him and his learners to explain events of the past in terms of the historical values of the time, as well as the pervasive attitudes and beliefs, and grounds these explanations in evidence. In addition, there are also aspects of different perspectives that he addresses.

He was able to identify and reflect upon the different beliefs and values such as communism, apartheid and negotiation represented by PW Both and Mandela that were current during the apartheid era. He identified communism which was perceived as an evil system by Botha and demonstrated how this belief made Botha to become ferocious against political activists perceived as communists. He also demonstrated the paradox between Mandela and Botha who came from different political ideological perspectives (Mandela a friend of the communists and Botha an enemy of the communists) but both valued the power of negotiation. He explored different perspectives of events even when they were conflicting narratives. For example, he presented evidence of Botha as a cruel apartheid authoritarian and also as a negotiator with Mandela to find solutions. This provides a full picture of the event at the time.

In describing PW Botha's regime and how he engaged learners in empathy, Moemi indicated that:

If you look at the pressure that he got from the National Party, the pressure that he got from outside and the availability of communism in Mozambique and Angola, you cannot shy away from empathising with him, he was telling the truth about the fact that communism was closer to South Africa than ever before.

Moemi, who belongs to the African community, teaching in a rural school where the learners come from a rural background and are poor because of apartheid, was able to put his emotions and anger aside and empathise with the man who was considered to have caused the South African nation to bleed during the battle between the youth and soldiers in the township. This assertion by Moemi also addresses elements of historical context as well as different perspectives. Moemi describes the circumstances that compelled Botha to embark on a campaign of "total strategy" against the youth in the townships and political activists. He contextualises the events of the 1980s, including the broader context to explain Botha's behaviour and controls his emotion about the killings of youth in order to interpret the decision taken by Botha as appropriate from Botha and National Party's perspective because it was dictated by circumstances at the time. Koso has noted that individual events and actions are understood by being situated in the larger context (cited in Huijgen, 2017:164) and this is what Moemi did by situating Botha's action within the context of the perceived communist threat in South Africa, which was attempting to colonise Southern Africa through the liberation forces trained by Soviet Union and China.

Lesson presentations

Masina utilised a video documentary entitled Inside the Vietnam War published by Jonathan Tower production (Scott, Cole & McCarty, 2008) to teach a Grade 12 class. The lesson was planned for 45 minutes but it took 90 minutes and the next teacher allowed it to continue after observing the presence of the researchers with the recording video camera. On his turn Masina focused in his lesson on Operation Rolling Thunder - aerial bombardment - and Operation Ranch Hand (the spreading of herbicides such as Napalm) and finally on the effectiveness of the guerilla war tactics used by the Vietcong. The video documentary revisits the Vietnam War through the use of archival footage and photographs together with first-hand accounts from numerous war veterans who reveal stories about covert operations and military strategy (Scott, Cole & McCarty, 2008). The method that he used was to allow learners to interact with particular events in the video. In the video learners witnessed the deployment of US troops by military aircraft in Vietnam. He paused the playing of the video and asked: "Who is telling the story in this documentary?" One learner responded: "Soldiers who participated in the war?" The teacher asked: "What type of a source is this?" Another learner said: "It is a primary source? The teacher probed: "Why is it a primary source?" Another learner responded: "The soldier telling the story was there during the war". The teacher asked another question: What are American troops spreading? And one learner responded: "Napalm, which is a chemical substance". The documentary revealed how the Americans ill-treated some of the Vietnamese people. American airstrikes killed ordinary people, women and children. The teacher asked: "How would you feel if you were a Vietnamese and you were invaded with guns and aircraft?" "How will you feel when ordinary people are shot at or burned by foreign forces?" "How would you feel if you were there, seeing foreigners attacking your people, hurting them and your country?" The teacher repeated the same question three times but in different form and in response one learner said: "I will be angry and sad"; another: "I will take action" In response to this the teacher probed "What action?" Another learner responded: "I will revenge to defend the country". He continued to play the video which showed how the Vietnamese troops, the Vietcong, embarked on a guerrilla war, using a tactical strategy that involved attack and retreat. The video detailed how the US used Napalm, a dangerous chemical substance, to destroy the Vietnamese but the Vietnamese nevertheless withstood the onslaught and many US troops were killed by the Vietcong. The video documentary also showed the Vietcong hiding in tunnels and using booby traps and launching surprise attacks. Masina did not focus on the resistance shown by the Vietnamese soldiers and neither did he analyse their battle strategies but continued to portray them as victims. Learners were able to interact during the lesson and participated effectively.

Masina asked questions that encouraged learners to be engaged in emotional empathy with the Vietnamese and some of these emotionally driven questions were asked repeatedly leading to some learners expressing anger and the desire for revenge. This certainly is not the ultimate goal of what proponents of the emotional domain of Historical empathy had in mind. There was congruency between the conception and teaching of Historical empathy because both teachers addressed only the emotional domain of Historical empathy. Instead of developing emotional control, learners were enraged and compared this treatment of the Vietnamese to their own experience during apartheid which according to the Barton and Levstik (2004) framework constitutes shared Normalcy. Learners could not demonstrate emotional control and did not even demonstrate elements of the cognitive domain such as a sense of "otherness" historical contextualisation and different perspectives.

In his lesson, Moemi, the second teacher, focused on the Vietnam War and taught a Grade 12 class. The lesson took 45 minutes. He focused on the battle strategies of the US as compared to the Vietcong and indicated that the US used aerial bombardment while the Vietcong utilised guerrilla war tactics. He used a group-discussion approach. Learners were given 15 minutes to explore the sources that were based on booby traps and tunnels as well as US aircraft flying over Vietnam. Learners engaged in group discussions with fellow learners. There were five groups and each group was given a single question on the Vietnam War. The question that he posed to the groups was as follows: Was it necessary for the US to be involved in the war with Vietnam, or not? Substantiate your answer with valid evidence. Each group presented their response to the question and the whole class was involved across groups and was further propelled by probing questions, seeking to elicit more evidence from the class. The teacher asked: "Why would the Americans go to extreme of attacking Vietnam?" One learner responded: "to prevent Vietnam from becoming a communist country" The teacher probed further: "Why did the US want to prevent Vietnam from becoming a communist country?" Another learner from a group responded: "to prevent it from influencing other neighbouring countries". In response to the initial key question one learner indicated that "Americans pursued the war because they want to colonise Vietnam" and the teacher asked whether it was possible for Vietnam to start the war, to which another learner responded and indicated that "Vietnam was a small country and cannot be aggressive against a strong country such as the US and the participation of the Vietnamese was aimed at defending their country against the coloniser US". Learners appeared fascinated by the guerrilla war tactics used by the Vietnamese and learners empathised with the Vietnamese and immersed themselves into their predicament. Learners did not judge the Vietnamese as weak due to the use of less powerful weapons against the American Aircraft which launched carpet bombing by dropping bombs carrying Napalm to be detonated via a remote control. So the learners' appreciation showed elements of humility and the learners did not become angry or emotional about the Americans but were appreciative of the strategies of the North Vietnamese soldiers.

This reveals the difference in strategy and resources used by the teachers. It is possible that a video documentary will provoke stronger emotions than a photograph of booby traps and Vietnamese soldiers hiding under grass covered with human waste such as those in the prescribed textbooks analysed by Ramoroka and Engelbrecht (2015). Some learners commented on sources that show the Vietnamese covered in human faeces as a demonstration that the Vietnamese were determined to defend their country against colonialism. Another learner indicated that: "Vietnam was tired ofbeing ruled by foreigners after the French occupation ended". There was no sympathy expressed by learners in this class and this was the result of the types of sources used and by a different teaching strategy which did not view the Vietnamese as victims.

Discussion

Moemi's knowledge of the concept Historical empathy reflected elements of the cognitive domain and he demonstrated this when he responded to an interview question based on Historical empathy. He gave an example of circumstances that led to the adoption of "total strategy" by PW Botha which, according to Moemi, was in response to the reality of communism in Southern Africa which in the view of many was threatening to wreak havoc in South Africa as it had in Eastern Europe. He indicated that members of the liberation forces in Southern Africa such as Frelimo (Mozambique), African National Congress, South African Communist Party (South Africa) and Umkhondo we Sizwe (the ANC military wing) were trained in China and Soviet Union and were possibly considered to be agents of communism. The Soviet Union had also colonised many Eastern European countries resulting in the killing of many people and many died of hunger because their economies were used to sponsor the Soviet Union's arm race against the US. Moemi saw the actions of Botha within the global context of the Cold War and by so doing he demonstrated elements of historical contextualisation. Moemi did not sympathise with the victims and his perspective was embedded within the realm of cognitive Historical empathy. He attempted to put himself in the shoes of Botha when he made a decision to embark on "total strategy" (in response to the perceived "total onslaught") in order to protect South Africa from the spectre of communism.

Moemi tried to understand the powerful forces by stepping into their shoes or tapping into their minds when taking decisions that affected ordinary people while Masina focused more on perceived victims of the Vietnam War. It is this empathy with victims that traps him within the emotional realm of Historical empathy.

The learners in Moemi's and Masina's classes seemed to empathise with the events of the Vietnam War from different vantage points. Therefore, Moemi's learners demonstrated maturity and understood the circumstances faced by the Vietcong against a strong power like America. However, Masina used the documentary developed in the US which display the aerial bombardment and he asked emotionally provoking questions and learners responded angrily. He did not focus on the military strategy of the Vietnamese soldiers. It is possible that this may have been caused by the limited time for the video documentary since it was divided into three parts. However, what was emphasised in the classroom was the cruelty of the Americans.

Moemi's learners saw the Vietnam War as part of the broader Cold War between America and Soviet Union and therefore demonstrated some elements of historical contextualisation. Masina's leaners remain within the emotional realm and in this context emotive empathy was not a stepping stone to cognitive empathy but an obstacle. This empirical evidence reinforces the argument advanced by Foster (2001) that emotions are an impediment to the attainment of Historical empathy. On the other hand, Moemi did not require emotional scaffolding to introduce his learners to some elements of historical contextualisation. These findings are in keeping with the two doctoral studies (Harris, 2016; Margery, 2017) where strong evidence of migration from the emotive to the cognitive domains was not demonstrated and therefore it can be inferred that emotional dimensions do not necessarily provide enabling knowledge for learners to attain the cognitive elements of Historical empathy.

Moemi attempted to show his learners the geographical proximity of Vietnam, Soviet Union and China and this was done in order for learners to analyse the circumstances that compelled the American policy makers and President Johnson to take the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution on August 7, 1964 which authorised the US to attack Vietnam and also to use chemical weapons in the process. It was assumed that the occupation of Vietnam would allow American troops to be present in Eastern Europe to monitor the activities of both Soviet Union and China, two powerful communist countries which were major players in the Cold War against the US. Masina highlighted the causes of the war but did not delve into the circumstantial evidence that compelled Johnson to go to war; he chose instead to focus on emotional empathy by sympathising with the Vietnamese people, perceived victims of the war they won.

There is an abundance of sources that can be used to engage learners in the cognitive elements of Historical empathy such as "otherness", different perspectives and historical contextualisation. According to the testimonies, some of the American troops felt they were misled that they were told they were deployed to Vietnam to protect democracy; these men felt betrayed by their government. Therefore learners needed to empathise with their predicament as well not just with the Vietnamese. This would demonstrate that Historical empathy is multi-perspective and includes both the victims and perpetrators and seeks to explain the circumstances that led to them acting in the manner as they did. The focus of the two teachers was one-sided: one focused on the victim and another on the strength of the Vietnamese soldiers and saw them as strategists rather than victims.

Conclusion

The article utilised the dual process of Historical empathy which embodies both the affective and cognitive domains as a theoretical framework. The research was driven by the following key question: To what extent can the concept of Historical empathy be utilised to engage learners in historical thinking in the classroom? The two teachers' conceptions of Historical empathy are related as both display the elements of affective domain. However, one teacher incorporated elements of the cognitive domain by demonstrating historical contextualisation as well as different historical perspective while another teacher remained with the emotional realm of Historical empathy. The conceptions of Historical empathy by the teachers influenced their selection of content and sources as well as their teaching methodology. It also influence their teaching methodology, video documentary was dominated by the teacher through his line of questioning and appears to propel learners towards emotional empathy. However, the second teacher's method of group discussions and the key question asked seem to provide a balance between Americans and Vietnamese perspectives because both entered the war to protect their own communities, the Americans were forced by circumstances to attack Vietnam in order to contain the spread of communism and Vietnamese fought in order to keep their independence. In Masina's class the Americans were seen as encroaching on the independence of Vietnam. This level of involvement in affective domain may overshadow the focus on critical elements of the cognitive domain. The learners who watched the video were enraged by the attacks on ordinary people and this did not lead to emotional control. It is recommended that a rigorous training be conducted by the Department of Basic Education in South Africa to ensure that the dual process of Historical empathy is realised especially in the context of History teaching being made (potentially a) compulsory from Grade 10 to Grade 12.The lesson learned is the Department of Basic Education needs to improve the teaching of both affective and cognitive elements of Historical empathy, and the focus should be to mediate teachers conception and misconception as the first step and the next step to assess if the their conceptions are realised in the classrooms. Finally, teachers must provide a balance perspective when teaching Historical empathy and should not be seen to be biased in support of the perceived weak or powerful forces.

References

Bailey, M 2017. Daily Maverick, 6 September. [ Links ]

Barton, KC & Levstik, LS 2004. Teaching History for the common good. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Bertram, C 2008. 'Doing History?' Assessment in History classrooms at a time of curriculum reform. Journal of Education, 45:155-177. [ Links ]

Black, DA 2014. Indoctrination to indifference? Perceptions of South Africa secondary school History education with special reference to Mpumalanga, 1960-1912. Unpublished Doctoral thesis. Pretoria: Unisa. [ Links ]

Bottaro, J, Visser, N & Worden, N 2013. In search of History Grade 11, Learners Book. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Boyatzis, R 1998. Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Britt, MA & Anglinskas, C 2002. Improving learners' ability to identify and use source Information. Cognition and Instruction, 20(4):485-522. [ Links ]

Bruner, JS 1986. Vygotsky: A historical and conceptual perspective. In: JV Wertsch (ed.). Culture, communication and cognition: Vygotskian perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Carland, J 2012. When did the Vietnam War start for the United States? Information paper, Arlington: Office of the Secretary of Defence. [ Links ]

Davis, OL Yeager, EA & Foster, SJ (2001). Historical empathy and perspective taking in the Social Studies. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Little Publishers, Inc. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education (2012). Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statements, History Grades 10 -12. Pretoria: DBE. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education (2008). National Curriculum Statements, History Grades 10-12. Pretoria: DBE. [ Links ]

Davison, M 2012. Teaching Historical empathy and the 1915 Gallipoli campaign. In: M Harcourt, & M Sheehan (Eds.). History matters: Teaching and learning History in New Zealand Secondary Schools in the 21st century. Wellington, New Zealand: NZCER Press. [ Links ]

Dugmore, C, Friedman, M, Minter, L & Nicol, T 2013. Spot on History Grade 12, Learners Book. Gauteng: Heinemann. [ Links ]

Dryden, S 1999. Mirror of a nation in transition: History teachers and learners in Cape Town schools. Unpublished MEd dissertation. Cape Town: UCT. [ Links ]

Elexandra, S, Cole J & McCarthy J 2008. Documentary: Inside the Vietnam War. Jonathan Towers production. [ Links ]

Elisabeth, DL 2008. Empathy as a tool for Historical understanding: An evaluative approach of the ancient Greek primary History curriculum. International Journal of Social Education, 23 (1):27-50. [ Links ]

Engelbrecht, A 2008. Role reversal in History textbooks after apartheid. South African Journal of Education, 28(4):519-541. [ Links ]

Fernandez, M, Wills, L, McMahon, P, Pienaar, S, Seleti, Y & Jacobs, M 2013. Focus History Grade 12, Learners Book. Cape Town: Maskew Miller Longman. [ Links ]

Grove, S, Manenzhe, J, Proctor, A, Vale P & Weldon, G 2013. Via Africa History Grade 12. Cape Town: Via Afrika Publishers. [ Links ]

Hamilton, C 2001. Mfecane aftermath: Reconstructive debates in Southern African History. Johannesburg: University of Witwatersrand Press. [ Links ]

Harris, R & Foreman-Peck, L 2004. Stepping into other people's shoes: Teaching and assessing empathy in the secondary History curriculum. International Journal of Historical Teaching, Learning and Research, 4(2):1-14. [ Links ]

Harris, ME 2015. Remembering Vietnam: Photographer who took Vietnam photo looks back, 40 years after the war ended. Available at https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2015/04/vietnam-war-napalm-girl-photo-today. Accessed on 20 March 2018. [ Links ]

Harris, BK 2016. Teacher Strategies for developing Historical empathy. Unpublished Doctoral Thesis. US. Walden University. [ Links ]

Huijgen, T, Van de Grift, W, Van Boxtel, C & Holthuis, P 2017. Teaching Historical contextualization: The Construction of a reliable observation instrument. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 32(2):159-181. [ Links ]

Kallaway, P 1993. History of education in a democratic South Africa. Gister en Vandag / Yesterday & Today, (26):10-18. [ Links ]

Lazarakou, ED 2008. Empathy as a tool for historical understanding: An evaluative approach of the Ancient Greek primary History curriculum. International Journal of Social Education, 23(1):27-50. [ Links ]

Margery, D 2017. Understanding Historical empathy in the classroom. Unpublished Doctoral Thesis. Massachusetts: Boston University. [ Links ]

Mbude, P 2018. City Press, 31 May. [ Links ]

Moses, AD 2005. The public role of History, Hayden White, traumatic Nationalism, and the public role of History". History and Theory, (44): 311-332. [ Links ]

Neumann, DC 2010. "What is the text doing?" Preparing pre-service teachers to teach primary sources effectively, Society of History Education. The History Teacher, (4):489-311. [ Links ]

Ramoroka, D (2016). A study of the central tenets of critical thinking in History classrooms. Unpublished Doctoral Thesis. Pretoria: University of Pretoria. [ Links ]

Ramoroka, D & Engelbrecht, A 2015. The role of History textbooks in promoting historical thinking in South Africa classrooms. Yesterday & Today, (14):99-124. [ Links ]

Reisman, A 2012. Reading like a historian: A document-based History curriculum intervention in urban high schools. Los Angeles: Routledge. [ Links ]

Rotter, AJ 1999. The causes of the Vietnam War, The Oxford companion to American military History. New York: Oxford UP [ Links ]

Seixas, P & Morton, T 2013.The big six Historical thinking concepts. Canada: Nelson Education Ltd. [ Links ]

Shulman, LS 1986. Those who understand knowledge growth in teaching. American Educational Research Association, 15(2):4-14. [ Links ]

Spector, RH 2018. Vietnam War, (1954-75). Encyclopaedia Britannica. Available at https://www.britannica.com/event/Indochina-wars. Accessed on 24 November 2018. [ Links ]

Stearns, PN, Seixas, P & Wineburg, S 2000. Knowing, teaching and learning History: National and international perspectives. New York: New York University Press. [ Links ]

Tharp, G & Gallimore, R 1988. Rousing minds to life: Teaching, learning, and schooling in social context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Van Drie, J & Van Boxtel, C 2007. Historical reasoning: Towards a framework for analyzing learners' reasoning about the past. Educational Psychology Review, 20 (2): 87-110. [ Links ]

Von Glasersfeld, E 1990. An explosion of constructivism: Why some like it radical. In: B Davis, CA Maher & N Noddings (eds.). Constructivist Views on the teaching and learning of Mathematics. JRME Monograph, Virginia: NCTM. [ Links ]

Vygotsky, LS 1978. Mind in society. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Waller, BJ 2009. How does historical literacy manifest itself in South African grade 10 History textbooks? Unpublished MEd dissertation. Durban: UKZN [ Links ]

Wineburg, S 1999. "Historical thinking and other unnatural acts". Phi Delta Kappan (80):488-499. [ Links ]

Wineburg, S 2001. Historical thinking and other unnatural acts: Charting the future of teaching the past. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. [ Links ]

Yilmaz, K 2006. Social Studies teachers' conceptions on History and pedagogical orientations towards teaching History. Unpublished Doctoral Thesis. US: UG. [ Links ]

ANNEXURE A: Evaluation criteria for the display of Historical empathy