Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Yesterday and Today

versión On-line ISSN 2309-9003

versión impresa ISSN 2223-0386

Y&T no.17 Vanderbijlpark jul. 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2223-0386/2016/n16a4

ARTICLES

"Word generation" and skills around learning and teaching History

Sarah Godsell

University of Johannesburg Soweto Campus. sdgodsell@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

The Word Generation Programme (WordGen), produced by Harvard University Education School in 2006, presents ways of engaging with and improving literacy skills in school going students. WordGen comprises a set of freely available lesson plans, structured to be taught every day throughout the week, that focus on students engagement with material and concepts through processes of discussion, debate, and perspective taking. The materials engage the students' everyday lives, as well as the knowledge that the unit is intended to teach. As everyday life examples are used, it is possible to imagine a contextual translation from the United States of America, to South Africa. This article explores the possibility of using the materials created by the Strategic Education Research Project (SERP) - who have pioneered the "WordGen" programme-as a basis to create materials for South African classrooms, specifically to teach History for the Intermediate Phase (Grade 4 - 6). In this article I argue that the WordGen lessons engage important skills for learning and teaching History. I outline the skills that are generated when History is taught in a compelling and iterative way and then engage with WordGen concepts and content and with the WordGen material specifically designed to teach History: SoGen. The article considers the case of third year education students at the University of Johannesburg and their responses to the WordGen material. The experiences gained from this translation into a tertiary context indicates that Word Generation may garner similar positive outcomes as those seen in the primary school context.

Keywords: "Word Generation"; History; History teaching; Intermediate Phase; Education students; History skills; Productive talk; Academic language.

Introduction

The course SOSHIA 3A, taught at the University of Johannesburg, aims to provide a historical overview at a university level which would allow the students to interact with the discipline of History. SOSHIA 3A, in 2016, comprised 13 students that I taught for one semester. I had one and a half hours a week to explore historical content and concepts, with these students who would, in one and a half years time, become history teachers. My experience of teaching History1 to third year students in the programme, "Education for the Intermediate Phase" surfaced several challenges. At the beginning of their third year, these students are two years away from being qualified as teachers, where they would run classrooms of their own. The reality that they have to comfortably conduct classes of their own in the near future is an ongoing concern of education students. As a result, it became clear that the students both desired and required their time in the History classes that I taught to engage them at dual levels. Firstly, it must teach them History: that is, historical content, historical thought, historical enquiry and how to conduct historical research (Keirn & Martin, 2012). Secondly, it needs to engage them as teachers: Why is History important for primary school students? What content will they need to teach? How will they engage the students and approach the subject? (See, among others Stearns, Seixas & Wineburg, 2000; particularly Ashby & Lee, 2000; Duhaylongsod et al., 2015; Peck & Seixas, 2008).

This brings us to how children think about, and learn, History. There are different approaches to and vast research into historical thought and enquiry in the classroom. Cooper outlines children's thinking in History, stressing the importance of processes of historical enquiry (Cooper, 2013). She stresses that "progress occurs through: trial and error, discussion, debate, having ideas challenged..." WordGen, pioneered by Harvard School of Education in 2006, focuses on teaching students academic vocabulary through repeated and in depth engagement with the vocabulary and the content contained therein. This occurs through discussion, debate, and perspective taking. Although started for secondary school, the programme has been expanded to primary school, and to include Social Sciences (SoGen). Topics of the 10 day (2 week) lesson plans include: What is fair? Where do I belong? Should everyone be included? Why should I care? and Why do we fight?

I argue that the (WordGen) materials facilitate children's thinking in History, can be used to get student teachers to interact with historical knowledge and conduct historical research, and at the same time hold their interest in how they will teach the subject. WordGen materials are useful in the development of some processes of historical enquiry: some of the processes involved include perspective taking:

Part C: Taking an Egyptian perspective

Imagine yourself in ancient Egypt. The Nile flood for the past few years has been low, and this year's flood is again dangerously low. Food stocks are so scarce that people grow angry and begin to revolt. They challenge the authority of the local government, marching, not working, and writing revolutionary graffiti on the walls of buildings in the southern city of Aswan. Using what you have learned today about Narmer, Khasekhemwy, Senusret III, and Hatshepsut, put yourself in Egyptian sandals and think about how they might have attempted to end the revolt in Aswan and restore order and stability.Would they act oppressively? Or would they do something else?2

Some of the topics covered in debate and discussion are:

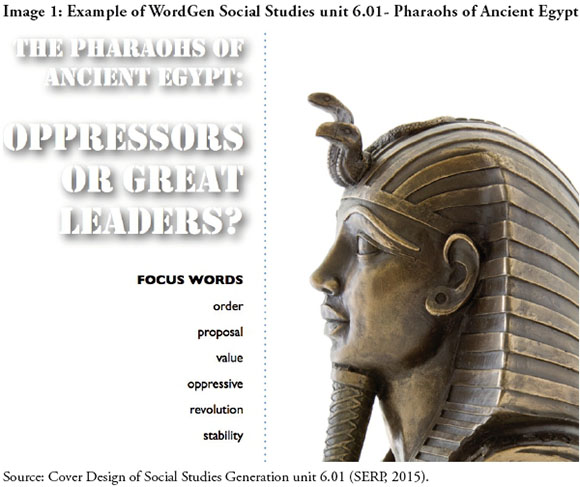

• Were the pharaohs oppressive rulers or great leaders whose actions were justified? (SocSt 6.01);

• Pyramids and Other Monumental Structures: Great Achievements or a Waste of Egypt's Surplus? (SocSt 6.02);

• Should the United States continue to give citizenship as a right of birth, or should it join the majority of developed countries in requiring that at least one parent be a citizen? In addition to providing arguments that support your position, address at least one counter-argument (SocSt 8.03).

Turn and talk

• Why do you think the Dutch and the British thought they were justified in taking land that belonged to others? Do you think that if they had compensated the Africans, it would have been okay? Why or why not? (SocSt 8.06)

WordGen and SoGen are effective in engaging with first and second order historical concepts (Ashby & Lee, 2000). However, the material is lacking in some elements: the processes of enquiry that require engagement with the provenance and reliability of sources, for example, are not in general strengthened by Word Generation materials. In these materials, while historical data is sourced, the provenance of the source does not become part of the lesson. Students are asked to reflect on the data gained from primary sources, and to think about what data gives them a specific perspective. The emphasis is placed on critical thinking and engagement about events of the past, and students understanding the concepts taught in the lesson in both past and present context. This engages the change from "memory-history to disciplinary history" (Bharath & Bertram, 2015:78; Lévesque, 2008). I argue that this engagement promotes skills associated with social, emotional, and cognitive development, outlined by Cooper (Cooper, 2013).

WordGen began their programme with the aim of improving literacy skills of middle and high school students but have since extended the project to encompass primary (in the United States of America system known as elementary) school, as well as the development of materials specifically designed to teach History. This article explores WordGen materials that have been developed as appropriate to both age (intermediate phase learners) and subject (History).

The process of destabilising unilinear "fact" (while paying attention to factual sources) to allow for multiple histories can be presented and explored through the WordGen materials. How do people come to have different opinions? Why do they have them? How do we choose what different facts to use to present arguments? These are all important parts of analytical thinking, and of a historian's work. Each version we have of the past, each History, each memory, is a valid informative portal, of different content and different ways of thinking. Some memories or narratives show how a group of people felt about a certain event, rather than a teleological narration of that event. How do we build histories that involve memory and positionality, power and agency? This is the work that historians engage, and engage in.

There are interlinked considerations for translating materials in differing contexts. I raise two critical factors for the South African milieu. The first is contextual translation and the second is attention to language. Insufficient attention to multiple spoken and written languages remains a consistent challenge, and potential resource, for promoting literacy and critical engagement in South Africa. There is potential for translation of concepts to support a multilingual classroom, while maintaining a fluency in one teaching language. Despite this there have been insufficient resources and care in harnessing this potential.

This paper first explores why History is an invaluable subject in school, looking at the aims and skills outlined by the National Curriculum Statement (NCS) and the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) documents. The WordGen programme and the CAPS document both emphasize the importance of discussion and debate as well as perspective taking. The article then engages with the WordGen concepts, and then with the WordGen material specifically designed to teach History: SoGen. Furthermore, I go on to explore the possibilities of translating this material for the tertiary teacher training level. As the example at the beginning of this article explains, I also consider the case of third year education students at the University of Johannesburg and their responses to the WordGen material. The experiences gained from this translation into a tertiary context indicates that WordGen may garner similar positive outcomes as those seen in the primary school context.

Word Generation: A cross curriculum engagement with academic literacy

WordGen is a programme started in 2006 under the Strategic Education Research Partnership (SERP, based at the Education School at Harvard University). The theory was developed through classroom discussion and debate. Academic language, perspective taking and complex reasoning are used to promote deep reading comprehension. Skills are enhanced through exposure to specifically chosen academic words. For example, the focus words from Unit 5.03 "Why should I care" are:

• obligation;

• moral;

• current;

• affect;

• motive;

• significant.

Exposure to these ideally happens in layered and textured ways, through a variety of methods, and over a variety of subjects. While this may not be possible across all subjects in schools, because of the already established curriculum and different subject teachers, it should be possible to promote an integrated approach to teaching (Snow, 2016; Duhaylongsod et al., 2015). WordGeneration is a structured lesson plan that can be implemented in class daily. The packs run over five lessons, or one week, with the week culminating in either an essay or a debate. Each daily lesson engages both with the content - that is subject specific - and the focus words that are intended to increase conceptual vocabulary.

When content is the primary curricular focus in History, historical thinking can be subjugated to factual content. The results of this are visible in the anxieties of third year students in my class at the University of Johannesburg, when dealing with exercises in historical thought and enquiry rather than historical fact. Although the students chose a more theoretically driven approach to the course at the beginning of the course, when we focused more on learning how to understand second order concepts they became uneasy, and wanted to know "what are we really learning". The WordGen materials helped to strike a balance between the two sides. This experience aligns with Shelly Weintraub's work "What's all this new crap? What's wrong with the old crap? Changing history teaching in Oakland, California" in (Stearns, Seixas & Wineburg, 2000:178-193) where she needed to convince the teachers of the value of teaching explicitly for historical thinking.

WordGen works extensively with debate, discussion, and perspective taking (which requires empathy), as well as conceptual vocabulary relevant to the lesson. Explicitly, WordGen works with first-order historical concepts: first order concepts being the things that history is made of: such as pharaoh, revolution, empire. However, implicitly, WordGen engages with second-order concepts as (being) concepts about history: continuity, change, cause and effect, use of evidence, and empathic understanding (Ashby & Lee, 2000). However, WordGen engages and facilitates these skills to different degrees. There is potential for heightening engagement with second order concepts, particularly those concepts to do with evidence and change over time. I argue that this is possible with the translation to the South African context. Seixas (2006) outlines historical thinking through laying out six structural benchmarks: "to establish historical significance, use primary source evidence, identify continuity and change, analyse cause and consequence, take historical perspectives and understand the moral dimension of historical interpretations" (Bharath, 2015:v). But as I will show below, WordGeneration itself does not engage all of these directly. However, I argue that the work of translation makes pre-service teachers engage with all six structural benchmarks nonetheless.

Focus words and reader's theatre: Examples of Word Generation

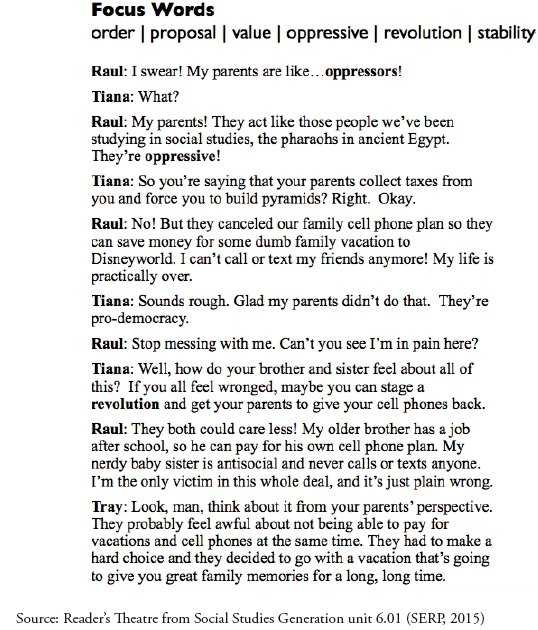

WordGen affords the possibility of expanding vocabulary, critical thinking skills and factual content knowledge through discussion and debate. It also encourages the development of some historian's skills such as perspective taking, synthesis and representation of information, and taking positions on arguments. There has been a sacrifice of some second-order concepts to promote others, and this remains a limitation of WordGen. For example, some primary sources, or lengthy, dense historical materials have been replaced with easier to access, historically accurate, but non-primary sources. This lessens the students ability to engage with primary historical sources. It does not impact the students engagement with historical material, as the historical information is in the sources. The WordGen packs carry content that is structured around a focus on reasoning, with evidence being provided to support the debate or essay that culminates and rounds up the week's work.3 The second-order concepts that are enhanced through word generation are primarily historical and present day perspective taking, and empathic understanding, also both present day and historic. Below is an example of focus words that convey first order concepts, and how these are integrated into a Reader's Theatre that pushes the thought-processes around these words.

The focus words (order, proposal, value, oppressive, revolution, and stability) cover both content and concepts for the unit. The themes are then presented through a Reader's Theatre piece, which contextualise the themes into the students' lives:

These pieces of reader's theatre offer a potential template for translating the ideas to a South African context. They work on translating the concepts to situations which resonate with the students' everyday lives, while remaining with where the concepts come from. This requires perspective-taking, and exercises in empathy, both historically and in present day contexts. These are important concepts in historical enquiry, and historical thinking (Seixas, 2006). Requiring pre-service teachers to think through these concepts first in the USA context, means that they have to understand how the concepts are being applied in both the present day context, as well as the historical context. The crucial step then to translate it into material for the South African classroom is to find relevant examples that will read for South African students. This requires pre-service teachers to think about who is likely to be in their classroom, and what ideas will resonate with them.

Although WordGen was initially aimed at high school students, there have been two subsequent initiatives which have developed materials both specifically for Social Studies subjects (SoGen) and for elementary (in South Africa called primary) schools, WordGen Elementary. The WordGen packs developed specifically to teach social science subjects provide both materials which can be adapted to the South African classroom, and a roadmap to creating WordGen packs around syllabus covered content. They also come closer to the specific focal points of teaching History. Particularly, perspective taking teaches the crucial concept for historical thinking: positionality. This is important because, as was discussed at the WordGen summer institute: "The degree to which any sentence in a History book pre-supposes a specific perspective is breathtaking" (Snow, 2016). The analytical skills which are required for historical thinking are also taught through vocabulary expansion, but rather than content focused vocabulary expansion, WordGen has focused on teaching academic language.

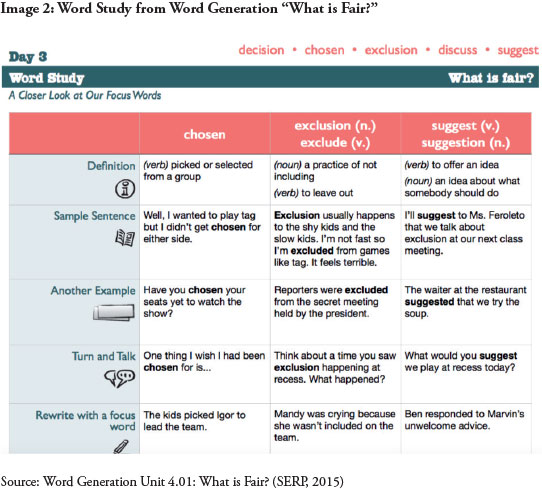

Academic language

Academic language is both the language of school and the language of reasoning. As Snow (2016) explained, "There is a lot of vocabulary that no one thinks about teaching" (Snow, 2016). Here she refers to much of the 'thinking' language necessary for complex reasoning and argument, or words used to carry lines of thought through complex text. Snow also stresses how important it is to have readers who can "hold" complex text. For example, a WordGen unit designed for primary school learners on "What is Fair" uses the focus words "decision, chosen, exclusion, discuss, suggest" (Strategic Education Research Partnership, 2015). These words are repeatedly used in different contexts in the material in the pack. These words cover both content and concepts needed to grasp the material in the pack. Importantly, words cover content concepts (such as exclusion) and thinking concepts (such as discuss and suggest).

Academic language is also useful in making the connections between concepts across subjects. This is another important aspect of WordGen, and where WordGen could be useful in a South African context: cross curriculum engagement. The importance of including academic language in the teaching programme helps students to nurture their own academic language so they can make their own arguments and articulate their perspective. This is important across the curriculum, as well as in aspects of life that exceed school learning. Initially, WordGen promoted a focus on vocabulary, but as the programme developed, the need to teach academic language, perspective taking, and argumentation became clear. At the same time, these skills are important for student teachers to learn for both their content and pedagogical skills. This question, posed in a presentation by O'Connor (2016) at the SERP WordGen Summer Institute, can be asked of our students and ourselves, "How do these things help me to deepen my own reasoning and understand someone else's?"

Language and translation: What is a concept?

In South Africa we have 11 official languages. This will have an irrevocable impact in the classroom. Third year students of Education for the Intermediate at the University of Johannesburg in 2016 expressed significant anxiety about managing several languages in the classroom. One student sighed when asked about how she would manage the multiple languages in the classroom. Another said: "It's difficult. We have to be able to jump between languages, sometimes languages that we don't even speak".4

Language in education is extremely contentious in South Africa. It is emotional, political, as well as crucial to the science of education. Linguistic interventions therefore have a quagmire of issues to navigate. This article does not attempt to spell out the myriad arguments in this field, but rather attempts to present WordGen materials as a potential practical tool for teaching History in primary school classrooms, that would support both the History skills called for in the CAPS document, and would have the potential to support teachers in multiple languages, allowing multilingual development (Cummins, 2000) through conceptually translating the key word provided in each unit.

There is strong disagreement in South Africa about the benefits, or necessity, or socio-political impact of code-switching, mother-tongue education, and language use in primary school classrooms. Henning writes "when we investigate the most successful school systems in the world, such as those in Finland and South Korea, we have to acknowledge that their early education is to a large extent 'monolingual' (Barber & Mourshed, 2007), even though English is studied as an additional language"(Henning, 2012:72). However, Cummins (2000) argues that conceptual knowledge can be developed across languages, that a concept understood in one language can help a student understand the concept in another language (Cummins, 2000).

It is important to unpack "concept development" itself, and what impact a multilingual classroom (significantly, using "code switching" (Henning, 2012)) has on the conceptual development ofyoung South African learners. Carey (2009) argues that language and concept development accelerated incrementally, hand in hand (Carey, 2009). However, Henning (2012) asks whether the complexity and diversity of language hybrids that we find in urban areas in South Africa hinder the development of how young learners engage with texts when the texts are presented in the formal version of a language (Henning, 2012).

It appears that deep concepts need to be developed in a language, where code-switching's transitions and switching in and out fluidly between languages could make it difficult for children to acquire deep concepts (Henning, 2012). How, though, are teachers to manage when there are many languages present in one class, and where concept development happens at different times, potentially in different languages, for different students? Could WordGen potentially offer a scaffolding, solidly in one language, with threads connecting to multiple languages?

Why History? History and the South African NCS CAPS syllabus

History as a subject should nourish critical thinking and analytical skills. This nourishment of critical thinking occurs when students are taught to engage in historical thinking, that is, they are taught how to think about why things happened (causality), how and why we see things the way we do (positionality), and the relative truth or import of different sources (veracity). This knowledge base is applicable and important to all subjects and in ongoing engagement with social and political life.

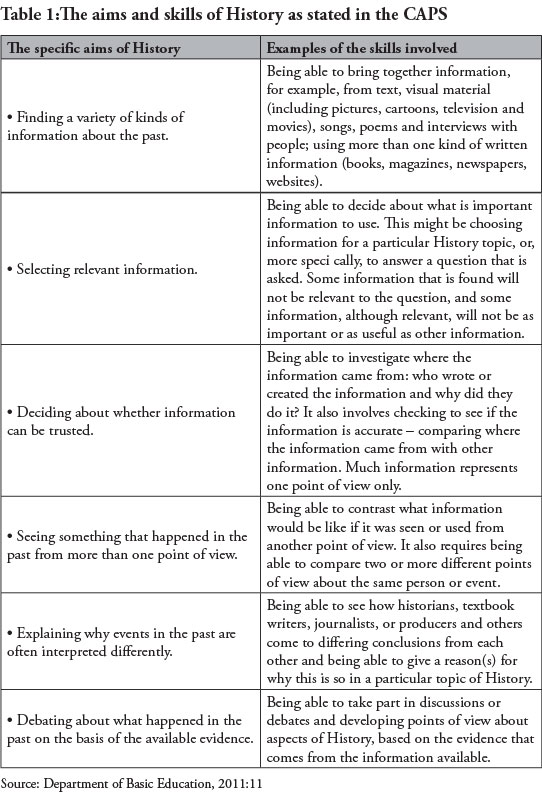

The following table from the CAPS document outlines the aims of History and the skills the subject facilitates:

These are second-order concepts, as defined by (Ashby & Lee, 2000) and explored by (Seixas, 2006). The outline demonstrates that second-order concepts are considered important in the South African curriculum, they are not expected to just be absorbed "by osmosis" as Seixas argues happens in Canada (Peck & Seixas, 2008:1021). The English National Curriculum, like the NCS in in South Africa, does focus on second order concepts. This does not appear to be case with the North American syllabi. What then, does it mean to adapt materials from the United States to use in South African classroom?

Some of the key skills outlined in the table above include: collating, verifying, and weighing up information (information analysis), developing and debating different viewpoints, (perspective taking), and deep comprehension of sources. These are some of the crucial skills that are the focus of the WordGen program. Moreeng (2014:768) argues that:

...History could be seen as having the potential to address most of the principles underpinning the South African curriculum, for example, social transformation, critical learning, and thorough knowledge of human rights, inclusivity and social justice.

Here, History includes a set of socio-political skills, as well as a set of academic skills. This is in turn conveyed through historical content. However, for History to encourage this thinking it needs to be taught as a skill set, not only as a knowledge repository. There are several ways in which the current NCS for the intermediate phase encourages this:

History is about learning how to think about the past, and by implication the present, in a disciplined way. History is a process of enquiry and involves asking questions about the past: What happened? When did it happen? Why did it happen then? It is about how to think analytically about the stories people tell us about the past and how we internalise that information (Department of Basic Education, 2011:10).

History then serves particularly as a link between the past and then present, but one that requires constant investigation and analysis. In its function as a tool to understand the links between the past and the present, History is also used to teach ideological tools, particularly those of political paradigms. The History syllabus is also expected to teach concepts of citizenship and leadership. The CAPS document outlines:

The study of History also supports citizenship within a democracy by:

1. explaining and encouraging the values of the South African Constitution;

2. encouraging civic responsibility and responsible leadership, including raising current social and environmental concerns;

3. promoting human rights and peace by challenging prejudices involving race, class, gender, ethnicity and xenophobia, and

4. preparing young people for local, regional, national, continental and global responsibility (Department of Basic Education, 2011:10).

While the linking of History teaching and citizenship teaching is contested (Lee & Shemilt, 2007)5, and the language of "responsibility" is similarly problematic, the analytic and critical skills required to engage with these civic education points remain valuable (Davies et al, 2002). They create the space for situating one's own position and the position of others in the world, understanding causality, and being able to debate these understandings.

If these parts of the syllabus are taught along with the critical thinking, analysis and research skills, then the content presented is opened to debate and complexity. Therefore, in teacher education, a History syllabus should ideally cover enough content to make the teachers comfortable in their subject matter, but, crucially, this content must be accompanied by stimulating student teachers to develop research and critical thinking skills. Thus, first and second-order concepts need to be taught (Stearns, Seixas & Wineburg, 2000). The teachers then need to pass these skills onto their students.

The benefit of using the WordGen in the tertiary classroom is that the teaching students themselves develop these materials that will develop both teacher students' skill and school learners' skill.

In South Africa the History syllabus has been anchored to promoting and entrenching ideological projects. Apartheid era (1948-1994) history as was taught in school is a particularly striking example of how History can be used to support, promote, and solidify structural inequalities (Chisholm, 1981). However, there are also more subtle and persistent ways in which History -and heritage - are used in school curricula to normalise particular values, ways of being, and ways of thinking (Moreeng, 2014). With this understanding, it is critical to provide students with tools with which to question the positionality and veracity of the materials, to examine their assumptions, and the assumptions of their teachers (Van Eeden, 2016).

Students need to be engaged deeply, at an appropriate level for their learning age, for these critical skills to be developed, and this prompts several questions: what materials can be used to supplement the already existing CAPS curriculum that could deepen the engagement of students in the primary school classroom? How can these materials be developed in a way that stimulates teachers' development and subject engagement? In what ways do these promote a holistic and thorough curriculum History classroom?

History in the Classroom: School and University

As this article has explored, the challenge presented in History classrooms is how to present information about the past in a way that provides students with sufficient content from the curriculum, but also involves them in the work of historical thinking. At the primary school level History provides an excellent space for incorporating some of the core principles of WordGen: perspective taking, debate and class discussion. These cover some of the second-order concepts discussed above: historical perspective taking, cause and effect, emphatic understanding. The second order concepts that WordGen doesn't explicitly cover, such as analysis of sources, or historic import, can be engaged with by pre-service teachers in the process of translating the packs to a South African context. Student teachers, in compiling WordGen packs, must engage with these questions. This deepens their own experience of their relationship to knowledge production. An awareness of this relationship is key for the History teacher, where the factual information selected to be taught in class is so important. It is pertinent to qualify what we see and use as "authentic" information.

An engaged History classroom should be attentive to the interplay and co-construction of "absolute truth" (e.g. the pyramids exist and can be roughly carbon dated) and the multiple angles and constructed meanings that relate to "facts" (e.g. the pyramids show the pharaohs as either wise investors or wasteful spenders6). WordGen materials - from the daily turn and talk exercises to the final debate and essay - encourage students to take a position on classroom topics. If students at a tertiary level (in this case SOSHIA 3A) present topics, they can then assess to what extent these are appropriate for their South African classrooms. This promotes an iterative process of teaching and learning where student teachers themselves take perspectives and positions in the debate, and prepare their classroom spaces accordingly.

Authenticity and presentism: What we say, how we say it; what we see, how we see it

One of the key things that the WordGen for Social Studies (SoGen) History modules has grappled with is how to avoid what is known as 'presentism', that is, looking at and thinking about the past through the lens and subjectivities of the present while still maintaining the authenticity or truthfulness of the historic sources with which we are working (Hunt, 2002).

Part of this centres on how close we can get to 'sources' - the closest being an oral source, hearing from a person involved, alive, present, at the time we are examining. However even this proximity is complicated. Portelli (1998:36) writes, "Oral sources tell us not just what people did, but what they wanted to do, what they believed they were doing, and what they now think they did"(Portelli, 1998:36). Godsell (2015) highlighted in theory and practice both present and past difficulties of fact, knowledge and power. Students in both school and university need to engage with ideas of 'truth', but understanding positionality plays an important part in this. Understanding why a particular position is taken by a particular person opens up different avenues of understand historical "truths", and opens the historical landscape.

White (2000:32) expands on this:

But what if historians didn't care about which version of events was true? The creation of a master narrative, so much a part of the project of social History, wasn't so much about finding a single truth but a way to talk about different experiences. To talk about both the experiences of mine workers and mine owners as part of a single History.

White's engagement with "truth" here needs qualifying: which version of events, whose memory, whose narrative, whose History is "true"? Again, these questions highlight the importance of perspective taking. The debates presented in WordGen require nuanced engagement with different facts and positions, and so make it particularly appropriate for teaching History.

SoGen and teaching History: An approach that understands students' contexts

WordGen presents an approach towards academic literacy and discourse and debate focused learning, as well as cross-curricular engagement. However, my proposal would be to use WordGen approaches to teach History in primary school classrooms in South Africa. The following section engages the research that went into developing materials specifically to teach Social Studies (SoGen) which has been outlined in (Duhaylongsod et al., 2015). Thus, this section engages in depth with (Duhaylongsod et al., 2015)'s paper, as the authors and constructors of SoGen.

The research that went into developing the SoGen packs focused on disciplinary literacy,7 disciplinary content, and discipline specific approaches. With regards to History, this covers some of the attributes described in the CAPS document (Department of Basic Education, 2011). Importantly, a decision was taken to focus on engaging with historical concepts, rather than focusing on teaching large amounts of historical content. The intent is to focus on students' ability to engage with the concepts, giving them opportunities to digest, and explain, what their understandings are. This focuses on engagement, which is intended both to boost confidence and encourage students to learn historical thinking (Duhaylongsod et al., 2015:602).

Here, as with moving from vocabulary expansion to academic language expansion, we move from disciplinary knowledge to disciplinary literacy. The discussion of History throughout this article argues the importance of the skills taught in History. As explained above, academic language and analytical reasoning are strengthened in WordGen by structuring lessons around understanding different perspectives, including a two-sided debate. This is particularly useful in History, where is it crucial to understand the existence of a myriad of past mindsets. SoGen is instructive:

Whether a developmental obstacle during early adolescence or a lack of relevant information and exposure accounts for adolescents' difficulty with past mindsets is unclear. But organizing relevant information around a two-sided debate may facilitate deeper contextualization, because defending one's own argument and weakening an opponent's argument motivates disciplined attention to comprehension of text (Duhaylongsod et al., 2015:600).

A central debate around the development of the SoGen History curriculum remains the depth of engagement with historical knowledge. This is because each lesson unit is designed to fulfil WordGen principles that will teach the skills of historical thinking (teaching History as a skills set), rather than just teaching the historical content, and focusing on teaching students historical knowledge (Duhaylongsod et al., 2015:600). I argue that a focus on the skill set and the historical concepts allows a deeper and more in depth engagement with historical knowledge, that is in the end more beneficial to students than a face-value engagement with a lot of historical content. The designers of SoGen did this by choosing core concepts in History and organising the content of the SoGen lesson units around these concepts. Importantly, the content is organised around the concepts in varying multiple contexts. These contexts are both historical and present day, allowing the students to engage the concepts in their own lives. (Duhaylongsod et al., 2015:601).

The context of the students' lives is invaluable in the process of translating to the South African context. This is where the major contextualization and translation of the WordGen packs will need to happen. The WordGen researchers provided examples of this with writing the historical content packs to teach History. They state that their goals were for students to engage intensely with historical topics, and for students to be supported to develop "a deep understanding of analogical concepts" (Duhaylongsod et al., 2015:606).

The focus of the units is in depth engagement with the historical world that the students are exposed to, and promoting thinking about what that world looked or felt like in the past, and why. Analogies with contexts that would be familiar to students' own lives facilitate this process. But what about the dangers of presentism? Is providing modern day analogies of historical situations not encouraging seeing everything through the lens of today's sensibilities and understandings? The researchers for WordGen argue the opposite, that in fact using present-day examples prevents presentism (Duhaylongsod et al., 2015:607).

The argument the authors make is that getting the students to engage with different ways that people may have experienced things in the past, while at the same time engaging their own feelings about their current context, makes it easier to grasp past worlds and contexts. The research around SoGen also engaged with several classic problems with teaching History, such as students possible disengagement with lengthy or dense historical texts. This weighs up different second-order concepts, and chooses engagement with concepts (for example) of cause and effect, change over time, historical perspectives and emphatic understanding over engaging with primary sources. The WordGen programme is not moving away from lengthy historical texts. Rather the aim is to motivate and engage students with multiple shorter and easily accessible texts, so as to gradually move them on to longer and more difficult texts (Duhaylongsod et al., 2015:607).

The process here is important. History is engaged with, but presented in a way that is accessible and 'motivating' for younger students. The number of texts allows for a multiplicity of voices and angles of History to be engaged, even briefly. Here positionality is being taught, as well as familiarizing students with a variety of types of historical text. However primary historical texts themselves can be hard to engage with, no matter how they are presented. The SoGen researchers also grappled with this problem. Their solution was to use "simulated primary sources". That is, fabricated materials that stand as primary sources, which demonstrate points of view, give historical information, but also engage the school pupil (Duhaylongsod et al., 2015:607).

The choice to use simulated, or fabricated, sources is controversial. However, the approach is useful in several ways. Even with easier to access sources students are still required to make interpretations about the information they are accessing, and they are still required to test those interpretations through discussion and debate. These engage the second order historical skills of perspective taking, understanding change and continuity, cause and effect, and empathic understanding. While it will be necessary for these skills to be engaged more explicitly, and developed more, the initial engagement is important. For this to happen in an accessible and motivating manner is crucial (Duhaylongsod et al., 2015:608).

The question of older students presenting their opinions on historical debates poses the question of how student teachers engage with historical material. My own research (Godsell, 2016) suggests that first year students also tend to engage with historical concepts rather than weighing in on historical debate. The SoGen units are themselves designed to teach teachers and students, to at the same time boost teachers' discipline knowledge and understanding and assist their implementation of instructional approaches, that focus on improving students' historical literacy. This happens through the teachers facilitating students' historical interpretations, rather than the teacher being a location of historical truth. This shifts the focus from a "right" answer, to students being required to make claims that they can support with evidence (Duhaylongsod et al., 2015:608).

This change in the teacher's role is also a part of decolonizing knowledge: the teacher curates the students' interaction with knowledge, rather than the teachers themselves being knowledge dispensers. Though this can result in historical inaccuracies (as SoGen researchers discovered in transcripts of students debates) Snow et al argue that the relationship to knowledge, and the movement towards historical argumentation, are more important in the learning process than correcting each historical inaccuracy as it comes up in debate (Duhaylongsod et al., 2015:608).

This raises questions of how to treat historical inaccuracies in the classroom, while allowing students to engage with sources and historical concepts. The difficulty is to keep the discussion, and debate, while still covering the content. Some of the particularities and questions on veracity in History will be dealt with in the next section. The SoGen researchers argue that "student engagement with History in these classroom debates outweighs the historical content problems" (Duhaylongsod et al., 2015:608).

The researchers make these considered, contentious, arguments that the potential historical inaccuracies (content inaccuracies) are outweighed by the relationship the students develop to historical ideas. I agree with this argument, and observed the same in my classes. While historical inaccuracies can (and must) be corrected relatively easily, getting the students to engage in historical ideas and debates is harder, but more crucial. The structure of the WordGen and SoGen material means that students engage with information in a way that is meaningful to them, that they can relate to their own lives and encounter and debate in discussions with their classmates. This means that, while there may be inaccuracies, students are likely to challenge each other, and students learn to substantiate their arguments and claims. This develops fluidity of fact, argument and knowledge.

Possibilities in a South African context

Word for word translation runs the risk of flattening concepts, and would then remain at a superficial level and not engage conceptually. However, each WordGen unit comes with a "Word Study" page, pictured below:

The above figure shows the various way three ofthe focus words are defined, explained, and contextualised in WordGen units. They provide the following possibilities for explaining and exploring the word: Definition, sample sentence, example, turn and talk, rewrite, cognate (not pictured), and choose a picture. I propose that for a WordGen class where discussion and debate would be happening in multiple languages, well-translated Word Study pages can provide a scaffolding and tool for both teachers and learners. The skills taught in WordGen are those of using academic language, discussion and debate, which promote analysis and reasoning.

These skills can be learnt in any language. The difficulty is, however, fluency in whatever the chosen language of instruction is, and what kind of deep concept learning is possible with different kinds of language input. Henning points out that long-term research still needs to be conducted in this field. (Henning, 2012).

The word study pages would need to be translated contextually to be applicable for South African learners. Studying a translation project that focused on concept and context translation, rather than just word translation, would also provide useful data on how concepts are conveyed and embedded in different languages. The next section will focus on outlining some issues around translation, and concept translation.

Practicalities in WordGen

Productive talk

An important consideration in South African classrooms is what language the classroom talk happens in. Productive talk is another important principle in WordGen. Professor Catherine O Connor explained that 'productive talk' is supposed to enable specific skills in children (O'Connor, 2016). With productive talk we want students to be able to describe and listen, to be able to state what they think (the focus here is on their thought process rather than on the right answer), to be able to ask and answer the question "why do you think that", to not give up when they don't understand what someone said or when someone doesn't understand them. Productive talk involves talk that supports improvement in reasoning, and in explaining reasoning. This is crucial in a History classroom, as reasoning and being able to explain the reasoning is important in understanding causality and positionality. Productive talk involves students externalising their own reasoning and working with others' reasoning.

O'Connor went on to describe exactly why talk and discussion are important in the classroom, beyond the immediate skill set development. Classroom talk reveals understanding and misunderstanding, so the teacher can gauge and intervene where necessary. Children also remember what they say: talk boosts memory for content and procedure. Classroom talk and discussion also supports academic language development and perspective taking (O'Connor, 2016).

These benefits, however, are offset by obstacles that teachers face with implementing productive talk in the classroom. The most substantial of these being time: classroom talk and debate take up time that teachers often feel should be allocated to covering content, when teachers are pressured to complete a syllabus. The WordGen materials can assist with this when they are based on material that is covered in the curriculum. Another obstacle to classroom talk is the students' reticence, but again, this can be managed in strategic ways, and WordGen suggests several tools.

At the crux of this is that we need to talk about what we are thinking. Reasoning is not just about coming up with the right answer, but as in maths or physics, about showing how you got to the argument you arrive at. Children need to be able to point to the different kinds of evidence that they used to make their argument, and show their thinking around that. Again, this is important in History, but it is also a useful life skill, and necessary if we are working towards decolonising education.

Possible ways forward: A glimpse into the classroom

If they do not cover specific content that is laid out in the national curriculum The WordGen packs may be difficult to incorporate into South African classrooms, especially across curricula. This article has outlined the WordGen programme, and why it aligns particularly with the skills taught and learnt in History. Now the article will briefly touch on how and why I have used WordGen materials in my classroom. I tried to achieve a balance in my classroom between factual historical knowledge, conceptual knowledge and historical thinking, and how these might be transferred to the primary school classrooms they will be working in. Students helped to achieve this balance: whenever the class or material became too heavily based in the subject knowledge of History with no links to the classroom, the students became bored. When we worked with WordGen materials, students would take the WordGen materials and adapt them to South African context and content. This forms part of a process to support pre-service teachers in becoming history teachers (Pendry et al., 1998).

Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe: Reader's theatre

This research intends to work with third year teaching students to generate research packs, and a list of focus words, that will span content covered in multiple curriculum areas. This research was started in 2016, but the major part of it will be carried out in 2017. An ethics application was carried out through the Department of Childhood Education, and the students were enthusiastic about creating materials to be publicly and freely available to be used in classrooms. While this did not come to fruition in 2016, I intend to further this research in 2017. There were two basic aspects of WordGen that we focused on in class- the idea of focus words, and discussion of language around them, and generation of Reader's Theatre materials in a South African context.

I observed in class that the class discussion happened in several languages, none of which was English. Because of my linguistic deficiencies, and because the language of instruction that we were working in was English, we switched back to English for the debate and discussion sections. However, for the turn and talk, or the group exercises, the students used languages common and comfortable to them. Through this, we explored the possible usefulness of WordGen materials that allows for talk, discussion, and concept formation in languages other than English. To support this, I propose further research into translating the lists of focus words, with the idea to translate them conceptually (so, to translate into paragraphs that explain the idea behind the words rather than simplistic one word translations). With "concept dictionaries"8 translated the teachers can know that their learners have a grasp on the meaning of the focus words in multiple languages, so that the conceptual and analytical development that needs to happen around the focus words can take place.

Adapting the Readers Theatre contained in WordGen to a South African context was an exciting task for the students, and an exciting marking process for me as their teacher. The Readers Theatre sections in WordGen are intended to present the content dealt with in the units in a way that is engaging to the learners. The content must be presented in a way where learners are drawn in to engage analytically and intellectually with the social issues contained in the content. However, these have to be presented in ways that connect to the learners' lives. We worked with the WordGen modules on Ancient Egypt as examples, and the students needed to construct their own WordGen material to teach Mapungubwe, (a complex pre-colonial African society that lived in present day South Africa between 1075 and 1220 AD), one of the topics in the CAPS grade 5 syllabus. The third year students took to the Reader's Theatre task particularly well, engaging current political issues to teach political hierarchies and structures in Mapungubwe. Below is an excerpt from one Reader's Theatre:

Excerpt: Reader's Theatre submission, SOSHIA 3A

Paul: Our country is like Mapungubwe John: What are you talking about?

Paul: I am talking about our President and the inkandla story.

Tom: Oh yah, our president is like the king of Mapungubwe

Paul: Yes, because Inkandla is built for the President and his family only.

John: The king of Mapungubwe lived at the hilltop, I do not understand how these two things mix together.

Tom: Me too I fail to understand, where are you going with this.

Paul: What I am saying is that our President has isolated himself from the community because he has money and the king of Mapungubwe lived at the top of the hill because it was believed he was communicating with the gods.

John: But the king of Mapungubwe was rich.

Paul: Yes but he did not use his power and the money.

Tom: There are similar things about the king of Mapungubwe and our President for example they both have body guards and they are rich.

Paul: I agree but the king of Mapungubwe did not take the money or belongings of his community members, unlike our President.

John: Yes our president used the state money to build inkandla.

Tom: That is not fair and is against our constitution.

Paul: My point exactly, now you both get my point.

The above is an example of the potential in setting education students the task of creating the "reader's theatre" aspect of the WordGen sessions. The use of Paul, John, and Tom as names points to a closer adherence to the USA WordGen names, thus the student has translated the ideas but not the people. In creating WordGen reader's theatre, it will be important that students create characters that they feel read to their own lives and their own classrooms. However, the use of the example and comparison with between President Zuma and Nkandla with the king of Mapungubwe shows an engagement and analysis with present day politics and a topic that can easily be engaged and discussed in class. While the student presents a surface skim of issues from one perspective, the possibilities for unpacking a comparison between ideas and engagements around Nklandla, and ideas and engagements around royalty at Mapungubwe, would be rich in terms of analysis, debate, critical thinking and perspective taking. The processes of perspective taking at work in the excerpt display the effectiveness of giving this as a task at university level. The student used a consistent argument to put their point across, convincing others to see things from another perspective. Although there are historical issues with the analogy, the critical analysis work, and the work of engaging both historical issues and students' current lives is clearly evidenced. This is clearly something that the student feels strongly about, which is also a positive indication of the effectiveness of the task. The WordGen materials are designed to present topics that the students will want to engage in, and then present issues in ways which encourage perspective taking. While the above presents merely one example of where I propose to take this project, it shows the potential for bringing WordGen strategies and materials into the tertiary teacher-education classroom.

Conclusion

For historical literacy to grow, history needs to be taught as a skill set rather than a knowledge repository. Word Generation approaches, particularly in the units created specifically to teach Social Science subjects, help students to develop these crucial skills through discussion and debate. This approach encourages students to engage with positionality and ideas of historical "truth". As students are pushed to take a position on a topic, and defend their position, they need to interact with the sources they are given or the research they do to construct arguments. This reinforces the need to critically analyse information, and understand different positions.

This article has argued the WordGen project, and more specifically the development that focused on the generation of WordGen materials for the social sciences, SoGen, can be engaged productively for the teaching of History in South African classroom contexts. I work from the premise that historical thinking and historical literacy, working with second order historical concepts, is crucial in the history classroom. WordGen and SoGen units focus on in depth engagement and support of the learners creating their own opinions from historical information. As this information is placed both in historical context, and in context that reflects realities of the students' everyday lives, the students are brought into close proximity with processes and concepts of history. The units touch on both first and second order skills - so, both the concepts around the "things" of history, and the concepts around the "why" of history. Debate, discussion, perspective taking and an encouragement of in depth engagement with all concepts facilitates engagement with historical concepts such as causality, positionality, continuity, and empathic historic understanding. These skills align with the skills pointed to in the CAPS National Curriculum statement, and so WordGen, rather than distracting from what teachers need to achieve (according to the Department of Education) can be used as a tool to help teachers engage students.

Where WordGen is contentious, and potentially lacking, is engaging with direct primary sources. While I have elaborated the reasons for this, I argue that getting pre-service teachers to engage and translate the materials for a South African context will make up for this lack: in compiling the historical information for the units, the students will have to engage with primary sources. WordGen materials can be helpful for South African education students to interact with, if some aspects are translated thoughtfully. The translation process needs to involve both language and context if it is to be helpful to teachers and beneficial to students' learning processes. The language translation could help teachers to manage multilingual classrooms, while maintaining conceptual and academic language development in English.

I propose furthering this research to broaden the exercises in the SOSHIA 3 classroom, and to translate WordGen packs to the South African context to use in South African school classrooms.

References

Ashby, R & Lee, P 2000. Progression in historical understanding among students age 7-14. In: PN Stearns, P Seixas, & S Wineburg (eds.). Knowing, teaching and learning History: National and international perspectives. New York: New York University Press. [ Links ]

Barber, M & Mourshed, M 2007. How the world's best performing school systems come out on top. Available at http://www.smhc-cpre.org/wp-content/uploads/2008/07/how-the-worlds-best-performing-school-systems-come-out-on-top-sept-072.pdf. Accessed on 8 June 2017. [ Links ]

Bharath, P 2015. An investigation of progression in historical thinking in South African History textbooks. Unpublished PhD thesis. Durban: University of KwaZulu Natal. [ Links ]

Bharath, P & Bertram, C 2015. Using genre to describe the progression of historical thinking in school history textbooks. Yesterday & Today, 14:76-98. [ Links ]

Carey, S 2009. The origin of concepts. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Chauvin R, Theodore K, 2015. Teaching content-area literacy and disciplinary literacy. SEDL Insights, 3(1). Available at http://www.sedl.org/pubs/catalog/items/insights-3-1.html. Accessed on 11 June 2017. [ Links ]

Chisholm, L 1981. Ideology, legitimation of the status quo and History textbooks in South Africa. Perspectives in Education, 3:134-151. [ Links ]

Cooper, H 2013. Children's thinking and History. Primary History, Summer: 16-17. [ Links ]

Cummins, J 2000. Language, power, andpedagogy: Bilingual children in the crossfire. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [ Links ]

Davies, I, Hatch, G, Martin, G & Thrope, T 2002. What is good citizenship education in History classrooms? Teaching History, 106:37-43. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education 2011.Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement: Grades 4-6 Social Sciences. Department of Basic Education. [ Links ]

Duhaylongsod, L, Snow, CE, Selman, RL & Donovan, MS 2015. Towards disciplinary literacy: Dilemmas and challenges in designing History curriculum to support middle school students. Harvard Educational Review, 85(4):587-608. [ Links ]

Godsell, S 2015. Blurred borders of belonging: Hammanskraal histories 1942-2002. Unpublished PhD thesis. Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand. [ Links ]

Godsell, S 2016. What is history? Views from a primary school teacher education programme. South African Journal of Childhood Education, 6(10). doi:10.4102/sajce.v6i1.485. [ Links ]

Henning, E 2012. Learning concepts, language, and literacy in hybrid linguistic Codes. Perspectives in Education, 30(3):66-77. [ Links ]

Hunt, L 2002. Against Presentism. Available at https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/may-2002/against-presentism. Accessed on 27 May 2016. [ Links ]

Keirn, T & Martin D 2012. Historical thinking and preservice teacher preparation. The History Teacher, 45(4):489-492. [ Links ]

Lee, P & Shemilt D 2007. New alchemy or fatal attraction? History and citizenship. Teaching History, 129:14-19. [ Links ]

Lévesque, S 2008. Thinking historically: Educating students for the twenty-first century. Toronto: University of Toronto Press Incorporated. [ Links ]

Moreeng, BB 2014. Reconceptualising the teaching of heritage in schools, Part 1: Exploration of the critical relationship between higher education and the development of democracy in South Africa. South African Journal of Higher Education, 28(3):767-786. [ Links ]

O'Connor, C 2016. Productive talk in the classroom. Paper presented at the SERP Word Generation Summer Institute, Graduate School of Education, Harvard University, Cambridge, 10 August 2016. [ Links ]

Peck, C & Seixas, C 2008. Benchmarks of historical thinking: First steps. Canadian Journal of Education /Revue Canadienne deL'éducation, 31(4):1015-1038. [ Links ]

Pendry, A, Husbands, C, Arthur, J & Davison J 1998. History teachers in the making. Philadelphia: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Portelli, A 1998. What makes oral History different? In: Oral History Reader. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Seixas, PC 2006. Benchmarks of historical thinking: A framework for assessment in Canada. University of British Colombia: Centre for the study of Historical Consciousness. [ Links ]

Snow, CE 2016. Word Generation. Paper presented at the SERP Word Generation Summer Institute, Graduate School of Education, Harvard University, 10 August 2017. [ Links ]

Stearns, PN, Seixas PC, & Wineburg SS (eds.) 2000. Knowing, teaching, and learning History: National and international perspectives. New York: New York University Press. [ Links ]

Strategic Education Research Partnership (SERP) 2015. Word Generation Unit 4.01: What is fair? Available at http://wordgen.serpmedia.org/t_elem.html. Accessed on 11 June 2017. [ Links ]

Van Eeden, ES 2016. Thoughts about the historiography of veracity or "truthfulness" in understanding and teaching History in South Africa. Yesterday&Today, 15(3):37-65. [ Links ]

White, L 2000. Speaking with vampires: Rumor and history in colonial Africa. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. [ Links ]

1 SOSHIA 3A: Social Sciences History for the Intermediate Phase, 2016, University of Johannesburg.

2 SocSt unit 6.1, "The pharoahs of ancient Egypt: Oppressors or great leaders?", SERP 2012 (available at SERP website: http://wordgen.serpmedia.org/social_studies.html, as accessed on 10 July 2017).

3 All WordGen materials, and research around the project available at http://wordgen.serpmedia.org/, as accessed on 12 July 2017). All WordGen materials used for this article have been sourced from here.

4 These observations come from ethnography conducted on the SOSHIA 3A students during class. Full ethics permission was obtained to conduct the study, and students gave their consent to being observed.

5 Lee and Shemilts (2007) provide a summary of the arguments. Some contestations are whether teaching History with concepts of citizenship would result in ideologically weighted, and so biased, History, or whether teaching the so-called 'mistakes' of History will facilitate so-called 'good' citizenship.

6 I am taking this example from the Social Studies Generation unit 6.01.

7 Disciplinary literacy, Chauvin and Theodore (2015) explain, teaches the skills, background knowledge, and concepts necessary to engage in a specific field and content area.

8 The Zenex Foundation produced something that reads as a concept dictionary that translated concepts relevant to Maths and Science in high-school. The translations of focus words would draw on this methodology.